The hyaluronic acid (HA) derivative Restylane is now the most common injectable soft tissue filler used for facial wrinkle augmentation. Although it is generally well tolerated and absorbed within months, nodule formation at the injection site has been documented.

A 62‐year‐old woman with a history of carcinoma of the breast six years previously was referred to a fine needle aspiration (FNA) clinic for biopsy of a subcutaneous facial nodule. On palpating the nodule six weeks prior to presentation she was referred for ultrasound examination; findings were reported as being consistent with a lymph node, raising concern of possible metastatic carcinoma of the breast. Serendipitously the same ultrasound examination led to discovery of a thyroid nodule that was aspirated and found to be papillary carcinoma, broadening the differential diagnosis of the facial nodule to metastatic thyroid carcinoma.

On physical examination the lesion was a 1 cm subcutaneous nodule overlying the lower third of the mandible, a location felt to be consistent with a slightly “high” submental node. However, the nodule had irregular contours on palpation, and although it could be moved over the underlying bone, seemed to be fixed to the overlying skin. No cellular material was obtained by initial sampling with a 27G needle. After instillation of local anaesthetic, two samples were taken with a 23G needle using Zajdela's technique.1 Direct smears were made for Diff‐Quik (Harleco, New Jersey, USA) staining; the needle was rinsed in CytoLyt (CYTYC Corp, Massachusetts, USA) for preparation of a Papanicolaou stained Thin‐Prep (CYTYC Corp, Massachusetts, USA) slide. Two cytospin slides were kept for potential immunoperoxidase staining.

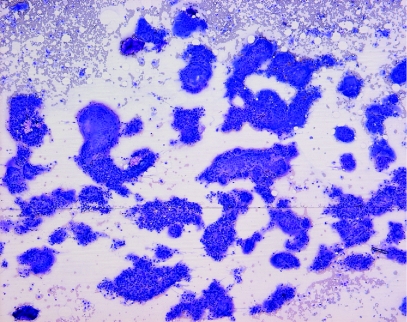

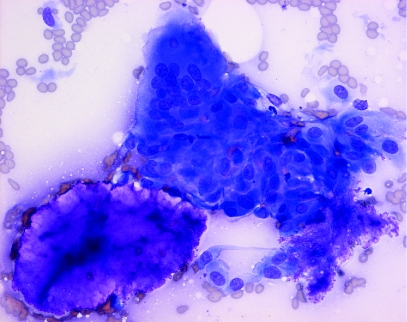

Microscopic examination of the Diff‐Quik stained sample showed a highly cellular specimen composed of two elements: histiocytes which were mainly aggregated to form foreign body type giant cells, and amorphous foreign material which stained a deep magenta colour on Diff‐Quik (fig 1). Staining of the foreign material, which was present in rounded masses measuring up to 300 μm in diameter, was homogeneous in some fragments, but granular material suggestive of degeneration or possibly calcium deposition was present in others. Some foreign material was seen lying free in the background of the smear, but most of it was seen in juxtaposition to giant cells, which appeared to be engulfing it (fig 2). Some giant cells showed “tears” in their cytoplasm which may have been caused during smear preparation; phagocytosed foreign material lagged behind as the surrounding cell was smeared flat. There was no evidence of malignancy, or of a chronic lymphocytic or suppurative inflammatory response.

Figure 1 Diff‐Quik stained smear showing foreign body giant cells, foreign material and dispersed histiocytes (original magnification, ×100).

Figure 2 Diff‐Quik stained smear contains rounded mass of Restylane with adjacent giant cell (original magnification, ×400).

Although paucicellular, the Papanicolaou stained Thin‐Prep slide recapitulated the findings of giant cells and foreign material seen on the air‐dried Diff‐Quik stained material. In the Papanicolaou stain the foreign material appeared light grey in colour, finely granular in consistency, and showed a slightly “frayed” edge. Occasional histiocytes were embedded in this material.

Further questioning of the patient revealed injection of Restylane at the site of the nodule ten months before. Because of the referring surgeon's concern that the observed acellular material might be thyroglobulin eliciting a giant cell response, the reserved cytospin slides were used for immunohistochemical staining for TTF‐1 and thyroglobulin (Ventana: TTF‐1 clone 8G7G3/1, thyroglobulin clone 2H11/6E1). These stains were completely negative. In view of the bland typical histiocytic morphology, it was felt unnecessary to restain these slides for CD68 and pan‐cytokeratin. Staging investigations undertaken before the patient's thyroid surgery did not reveal any evidence of recurrent breast carcinoma. Thyroidectomy confirmed a 1.6 cm papillary carcinoma limited to the thyroid. Six months after the needle biopsy the patient reports that the facial nodule has completely resolved.

Discussion

HA derivatives such as Restylane are among the most utilised soft tissue filler substances, principally being used as a non‐surgical cosmetic option for skin augmentation to correct age related skin facial wrinkling, or for treatment of post‐surgical and post‐traumatic skin defects.

Restylane is manufactured by bacterial fermentation techniques, and its biological characteristics generally allow high tolerance. However, it is not totally non‐immunogenic and is said to be contraindicated in patients with autoimmune diseases, or patients taking immunosuppressant therapy.3 The short‐term adverse effects of injection may include a transient acute inflammatory response in about 4–5% of patients, manifested clinically as redness, bruising, pain and swelling localised to the site of the injection.48 A few reports describe a delayed inflammatory response consisting of a granulomatous foreign body reaction occurring at the site of the injection.2,4,5 The aetiology of this granulomatous reaction has been ascribed to protein impurities resulting from the bacterial fermentation.6 To the best of our knowledge this is the first report of diagnosis of this reaction by fine needle aspiration biopsy. In addition to illustrating the feasibility of FNA diagnosis of Restylane granuloma, this case highlights the value of early cytological evaluation of a palpable lesion, especially with immediate assessment of a smear while the patient is still available for questioning. The information obtained is frequently sufficient to correct erroneous conclusions arising from non‐specific imaging findings, rule out other clinically suspected lesions and point to the correct line of inquiry required for diagnosis.

The strong magenta coloration of the Restylane we observed on Diff‐Quik staining could conceivably be mistaken for rounded bodies of basement membrane material, colloid, or mucin, prompting differential diagnoses of various salivary gland, thyroid, or breast neoplasms, but those possibilities are easily ruled out by the absence of any observed epithelial component, or, if necessary, by staining for cytokeratin. The finding of a foreign body giant cell reaction in FNA material from a facial lesion should prompt further questions about use of injectable filler substances in the area. As this case illustrates, the granulomatous reaction that occasionally occurs with these materials may only be recognised by the patient some months after their injection, and history of their use may not be offered initially.

Cytopathologists or pathologists seeing similar lesions might be questioned about appropriate treatment. Surgical removal is curative but may be of cosmetic concern to the patient. Local injection of steroids has been used with some success.7 Our patient was managed conservatively without the use of steroids, and the nodule has disappeared. It is possible that the partial removal of the foreign material by the needle biopsy may have accelerated the resolution of the lesion.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Zadela A, deMaüblanc M T, Schlienger P.et al Cytologic diagnosis of periorbital palpable tumours using fine‐needle sampling without aspiration. Diagn Cytopathol 1986217–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jordan D R. Delayed inflammatory reaction to hyaluronic acid (Restylane) Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 200521401–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghislanzoni M, Bianchi F, Barbareschi M.et al Cutaneous granulomatous reaction to injectable hyaluronic acid gel. Br J Dermatol 2006154755–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duranti F, Salti G, Bovani B.et al Injectable hyaluronic acid gel for soft tissue augmentation. A clinical and histological study. Dermatol Surg 1998241317–1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rongioletti F, Cattarini G, Sottofattori E.et al Granulomatous reaction after intradermal injections of hyaluronic acid gel. Arch Dermatol 2003139815–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman P M, Mafong E A, Kauvar A N.et al Safety data of injectable nonanimal stabilized hyaluronic acid gel for soft tissue augmentation. Dermatol Surg 200228491–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shafir R, Amir A, Gur E. Long‐term complications of facial injections with Restylane injectable hyaluronic acid. Plast Reconstr Surg 20001061215–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]