Abstract

Our study examined ethanol self-administration and accumbal dopamine concentration during κ-opioid receptor (KOPr) blockade. Long-Evans rats were trained to respond for 20 min of access to 10% ethanol (with sucrose) over 7 days. Rats were injected s.c. with the long-acting KOPr antagonist, nor-binaltorphimine (NOR-BNI; 0 or 20 mg/kg) 15–20 h prior to testing. Microdialysis revealed a transient elevation in dopamine concentration within 5 min of ethanol access in controls. NOR-BNI-treated rats did not exhibit this response, but showed a latent increase in dopamine concentration at the end of the access period. The rise in dopamine levels correlated positively with dialysate ethanol concentration but not in controls. NOR-BNI did not alter dopamine levels in rats self-administering 10% sucrose. The transient dopamine response during ethanol acquisition in controls is consistent with previous results that were attributed to ethanol stimulus cues. The altered dopamine response to NOR-BNI during ethanol drinking suggests that KOPr blockade temporarily uncovered a pharmacological stimulation of dopamine release by ethanol. Despite these neurochemical changes, NOR-BNI did not alter operant responding or ethanol intake, suggesting that the KOPr is not involved in ethanol-reinforced behavior under the limited conditions we studied.

Keywords: Ethanol self-administration, Operant, Microdialysis, Nucleus accumbens, Nor-binaltorphimine

1. Introduction

Converging evidence suggests that interactions between mesolimbic dopamine and opioid systems contribute to the development of ethanol reinforcement and dependence (Herz, 1997; Cowen and Lawrence, 1999). The endogenous opioid system exerts opposing effects on mesolimbic dopamine activity and motivational processes. For example, activation of μ-opioid receptors in the ventral tegmentum stimulates dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens (Leone et al., 1991; Spanagel et al., 1992; Devine et al., 1993) and produces conditioned preferences for an environment associated with administration of an agonist (Bals-Kubik et al., 1993; Nader and van der Kooy, 1997). In contrast, activation of κ-opioid receptors (KOPr) within the mesolimbic circuitry decreases dopamine neuron firing (Margolis et al., 2003) and inhibits accumbal dopamine release (Heijna et al., 1990; Spanagel et al., 1992; Xi et al., 1998). Additionally, the administration of selective KOPr agonists causes conditioned-place aversions (Mucha and Herz, 1985; Bals-Kubik et al., 1993) and a suppression of drug self-administration (Lindholm et al., 2001; Mello and Negus, 1998; Xi et al., 1998).

Although the functional significance of mesolimbic dopamine activity during ethanol reinforcement remains a subject of debate, there is evidence that dopamine transmission is involved in certain aspects of ethanol self-administration. Local blockade of dopamine transmission within the accumbens curtails operant responding for ethanol (Rassnick et al., 1992; Samson et al., 1993; Hodge et al., 1997) but not necessarily intake (Czachowski et al., 2001). Disruption of dopamine signaling alters ethanol consumption in naïve animals but not those with prior drinking experience (Ikemoto et al., 1997), suggesting that a functional dopamine system facilitates the learning of ethanol reward. Furthermore, operant procedures, in which responding is segregated from ethanol drinking, demonstrate that accumbal dopamine levels increase briefly upon acquisition of ethanol reinforcement but not thereafter (Doyon et al., 2003, 2005), an effect attributed to a role of dopamine in incentive salience. The issue of whether specific opioid receptor subtypes regulate mesolimbic dopamine activity during operant ethanol self-administration has not been addressed.

Endogenous opioids modulate ethanol-reinforced behavior (Gonzales and Weiss, 1998; Roberts et al., 2000; Hyytia and Kiianmaa, 2001). However, the involvement of the KOPr system is not clear. KOPr blockade with low doses (3–5 mg/kg) of nor-binaltorphimine (NOR-BNI) does not alter ethanol consumption during operant self-administration (Williams and Woods, 1998; Holter et al., 2000). Support for KOPr-ethanol interactions comes from studies demonstrating that tissue levels of dynorphin (the endogenous KOPr ligand) increase in the nucleus accumbens within 30 min of ethanol administration (Lindholm et al., 2000; Marinelli et al., 2005) and KOPr mRNA in the accumbens and ventral tegmentum is downregulated after repeated ethanol exposure (Rosin et al., 1999). The latter finding is suggestive of a compensatory response to enhanced dynorphin stimulation of the KOPr.

The aim of the current study was to determine the effect of systemic KOPr blockade on ethanol consumption and accumbal dopamine concentration using an operant self-administration procedure that distinguishes responding from ethanol ingestion. Our working hypothesis was that ethanol self-administration induces the release of endogenous dynorphin peptides, which activate the KOPr, and function to inhibit ethanol consumption and dopamine activity. Microdialysis was performed during self-administration of 10% ethanol (plus 10% sucrose) in rats pretreated with saline or the long-acting KOPr antagonist, nor-binaltorphimine (20 mg/kg). We quantified intra-accumbal dopamine and ethanol concentrations following ethanol access to assess the relationship between ethanol levels and the accompanying dopamine response. Ethanol intake and patterns of ingestion for both treatment groups were also quantified for comparison with the neurochemical data.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Subjects

Male Long-Evans rats (n = 35; Charles River Laboratories Inc., Wilmington, MA, USA) that weighed between 295–501 g at the time of testing were used. Rats were handled and weighed for at least 4 days upon arrival prior to surgery and training. Each rat lived individually in a humidity and temperature-controlled (22 °C) environment under a 12-h light/dark cycle (on at 7:00 A.M.; off at 7:00 P.M.). The rats had food and water available ad libitum in the home cage except during the procedure indicated below. All procedures complied with guidelines specified by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Texas at Austin and the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

2.2. Surgery

Prior to operant training or testing, we surgically prepared the rats for microdialysis by inserting a stainless steel guide cannula (21 gauge; Plastics One Inc., Roanoke, VA, USA) above the left nucleus accumbens. The surgery occurred while the rats were under isoflurane anesthesia (1.5–2.5% in 95%/5% O2/CO2, 1–2 L/min), using standard stereotaxic equipment. The following coordinates were used (in mm relative to bregma): +1.7 anterior-posterior, +1.0 medial-lateral, −4.0 ventral to the skull surface (Paxinos and Watson, 1998). The guide cannula was cemented to the skull by embedding three stainless steel screws into the skull and covering the entire unit, around the base of the cannula, with dental cement (Plastics One Inc.). A single steel bolt was placed vertically into the hardening cement as an anchor for the microdialysis tether. An obturator was placed inside the guide cannula to prevent blockage prior to the microdialysis session. After at least 4 days of recovery, the rats began the training procedure.

2.3. Microdialysis

The microdialysis probes were constructed according to the methods described byPettit and Justice (1991). Briefly, fused-silica tubing (inner diameter = 40 μm; Polymicro Technologies, Phoenix, AZ, USA) formed the inlets and outlets of the probes, and hollow cellulose fiber (inner diameter = 200 μm; molecular weight cutoff = 18,000; Spectrum Laboratories Inc., Rancho Dominguez, CA, USA) formed the dialysis membrane. The active dialysis membrane spanned 2.2 mm (the distance between the end of the inlet and the epoxy that sealed the membrane).

Habituation to the microdialysis tethering apparatus occurred within the week preceding testing. This procedure consisted of tethering the rats overnight in the operant testing room, with continued tethering throughout the subsequent day of self-administration training. Rats were sedated with 2% isoflurane in air for a few minutes to attach the tether. On the day preceding the dialysis session, we perfused (flow rate = 2 μl/min) the microdialysis probes with artificial cerebral spinal fluid (149 mM NaCl, 2.8 mM KCl, 1.2 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgCl2, and 0.25 mM ascorbic acid, 5.4 mM D-glucose), and slowly inserted the probes into the brain through the guide cannula while the rat was briefly anesthetized (15–20 min) with 2% isoflurane in air. This procedure occurred at least 14 h before the start of the experiment. We used a syringe pump (CMA102; CMA, Solna, Sweden) to pump the perfusate through a fused-silica transfer line and into a single channel swivel (Instech Solomon, Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA), which hung from a counterbalanced lever arm (Instech Solomon). The swivel formed a connection with the inlet of the probe and a spring tether secured the animal to the swivel. The perfusion flow rate was set at 2.0 μl/min during the probe implantation, after which it was decreased to 0.2 μl/min overnight. The flow rate was returned to 2.0 μl/min 2 h prior to baseline sampling. We manually changed each of the sample vials, which were immediately frozen on dry ice (excluding the fraction of dialysate that was removed for ethanol analysis, see Section 2.10) and then stored at −80 °C until analyzed.

2.4. NOR-BNI blockade of U50488H

Rats were injected with 20 mg/kg nor-binaltorphimine dihydrochloride (National Institute on Drug Abuse; Tocris Cookson Inc., Ellisville, MO, USA) in 1.5 ml saline (subcutaneously, s.c.) 15–20 h prior to the experiment. Previous studies indicate that this dose of NOR-BNI is selective for the KOPr (Takemori et al., 1988; Endoh et al., 1992). The microdialysis probes were inserted into the nucleus accumbens, and the protocol for the preparation of the microdialysis experiments was identical to that described in Section 2.3, excluding the tethering procedure. On the subsequent testing day, 3 baseline samples (10 min each) were taken using standard ACSF as the perfusate. After removal of the third baseline sample, the perfusate was switched to one containing the KOPr agonist (–)-trans-(1S,2S)-U-50488 hydrodrochloride (Clark and Pasternak, 1988; 0.4 or 1.6 μM; Sigma-Aldrich Inc.). Six 10-min samples were taken following the switch to U50488H. The flow rate was set at 2.0 μl/min for the entire experiment. Control rats received an injection of saline (1.5 ml, s.c.) 15–20 h prior to the experiment. Each group consisted of 3–4 subjects.

2.5. Behavioral apparatus

Standard operant chambers (Med Associates Inc., St. Albans, VT, USA) modified for microdialysis perfusion were used for self-administration training and microdialysis testing. One wall of each chamber contained a retractable lever on the left side (2 cm above grid floor), which upon activation triggered the entry of a retractable drinking spout on the right side (5 cm above grid floor). Each lever press activated a cue light above the lever. The floor consisted of a grid of metal bars in connection with the spout of the drinking bottle, which upon contact formed a circuit to record licks (Med Associates Inc.). A cubicle with the front doors left open during training and testing housed each operant chamber. PC software provided by Med Associates controlled operant chamber components and acquisition of lickometer data. Activation of an interior chamber light and a sound-attenuating fan accompanied the start of each operant session.

2.6. Self-administration training

Operant sessions occurred once a day for 5 days per week. The subjects were trained initially to lever press for access to 10% sucrose (w/v). Animals were water deprived (10–22 h) prior to each session (approximately 45 min) to facilitate acquisition of the operant response. Reliable lever pressing for sucrose occurred in approximately 2–5 days. Rats were not water restricted at any time during the subsequent training periods.

After reliable operant behavior was established, subjects were trained to self-administer 10% ethanol with 10% sucrose using a modified version (Doyon et al., 2005) of the sucrose fading procedure (Samson, 1986), in which the concentration of ethanol (v/v) in the drinking solution was increased across daily sessions (2–10% over six days), but sucrose was not subsequently removed. During this period, the rats were gradually habituated to: (1) a 15 min ‘‘wait time’’, which preceded access to the lever and drinking solution; and (2) a response requirement (RR) that increased from 2 to 4 across seven sessions (Table 1). Upon completion of the RR, the lever retracted and the drinking solution became available for 20 min, followed by a 20-min post-drinking period in the absence of the drinking solution. For the dialysis experiment, the response requirement was set at 4 and 10% ethanol (plus 10% sucrose) served as the reinforcer. Consumption was monitored during training and during the microdialysis session by a lickometer and by measuring the volume of liquid in the drinking bottle before and after the session, taking care to account for spillage. Body weights were measured each day.

Table 1.

Summary of operant training protocol for ethanol (plus sucrose) self-administration

| Day | Drink solutiona | Pre-drink wait (min) | Response requirement |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10S | 2 | 2 |

| 2 | 10S 2E | 4 | 2 |

| 3 | 10S 2E | 6 | 2 |

| 4 | 10S 5E | 8 | 2 |

| 5 | 10S 5E | 10 | 4 |

| 6 | 10S 10E | 12 | 4 |

| 7b | 10S 10E | 15 | 4 |

The sucrose control group followed the same schedule except that ethanol was not faded into the drink solution.

S equals sucrose and E equals ethanol. Numeral for drink solution represents percentage (w/v for sucrose; v/v for ethanol).

Dialysis session.

To control for the effects of sucrose in the drinking solutions, an additional group of rats were trained to self-administer a 10% sucrose solution that did not contain ethanol. The habituation procedure to the 15-min wait time and the response requirement was identical between the groups.

2.7. Experimental design

Rats were injected with NOR-BNI (20 mg/kg in 1.5 ml saline, s.c.) or saline (1.5 ml, s.c.) 15–20 h prior to the experiment. Dialysate samples were collected every 5 min except where indicated below. The microdialysis experiments consisted of four general sampling epochs: (1) home cage baseline; (2) transfer/wait; (3) drink; and (4) post-drink. Six samples were collected during a baseline period in the home cage (30 min). One sample was collected during the period in which the rat was transferred into the operant chamber prior to activation of the operant program (5 min). Upon activation of the program, three samples were collected prior to introduction of the drinking spout: two 5 min samples during a waiting period and a third waiting sample (approximately 5.7 min), which included at its end a brief lever-pressing period (0.7 ± 0.2 min). Completion of the response requirement was followed by a 20 min drinking period with unrestricted access (four samples) and then a post-drinking period within the chamber in the absence of the solution (20 min, four samples). At the end of this time, the rat was returned to its home cage. An additional 6 samples (at 10-min intervals) were then collected to monitor ethanol concentrations in the dialysates, but these samples were not analyzed for their dopamine content. After obtaining all samples, the perfusion solution was switched to one lacking calcium for 60–90 min. A 10-min sample was then taken to determine the calcium dependency of the dopamine in dialysates, which is an index of vesicular release.

2.8. Histology

Within 5 days after each experiment, the rats were overdosed with pentobarbital (300 mg/kg; i.p.) and saline was perfused through the heart, followed by 10% formalin (v/v). The brains were removed and immersed in 10% formalin/30% sucrose (w/v) for at least 3 days. Brains were cut into coronal sections (48 mm thick) with a cryostat (Bright Instrument Co., Cambridgeshire, England), and the sections stained with cresyl violet. The slides were examined to confirm the placement of the active dialysis membrane (2.2 mm). We determined correct placement within the accumbens when at least 55% of the active dialysis membrane bisected the core, shell, or core plus shell.

2.9. Dopamine analysis

Our HPLC systems were amperometric and based on reversed phase chromatography using an ion-pairing agent with electrochemical detection. These systems included one of two pumps [a LC-10AD (Shimadzu Scientific Instruments Inc., Columbia, MD, USA), or a LC-10ADVP (Shimadzu Scientific Instruments Inc.)], one of two autosamplers [FAMOS (LC Packings, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) or ALEXYS (Antec Leyden BV, Zoeterwoude, Netherlands], a VT-03 cell (2 mm working electrode diameter, potential: 450 mV against a Ag/AgCl reference; Antec Leyden BV) in connection with an Intro controller (GBC Separations Inc., Hubbardston, MA, USA) and a Polaris 2 × 50 mm column (C18, 3-μm particle size; Varian Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA). The mobile phase consisted of octanesulfonic acid (2.0 mM), decanesulfonic acid (0.2 mM), methanol (15%, v/v), sodium dihydrogen phosphate dihydrate (71.0 mM), and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (0.3 mM). The flow rates were set at 0.3 ml/min for both systems. For the NOR-BNI-U50488H experiments, 17 μl of the dialysate was injected using the microliter pickup mode and the transfer fluid was ascorbate oxidase (EC 1.10.3.3; 102.3 units/mg; Sigma-Aldrich Inc., St. Louis, MO, USA). For the ethanol self-administration experiments, 7 μl of the dialysate was injected. A computerized data acquisition system (EZ Chrome Elite; Scientific Software Inc., Pleasanton, CA, USA) recorded the dopamine peaks. Quantification was carried out by comparing dopamine peak areas from dialysate samples to external standards.

2.10. Ethanol analysis

Ethanol concentrations were analyzed in all dialysis samples collected after the lever-press period for subjects in the ethanol self-administration experiments. Before freezing the dialysis sample, 2 μl of fluid were transferred into a glass vial and sealed with a septum for analysis of ethanol later that day. A gas chromatograph (Varian CP 3800; Varian Inc.) with flame ionization detection (220 °C) measured the ethanol in the dialysates. Specific details concerning the components of the gas chromatograph are described byDoyon et al. (2003). Quantification of ethanol in dialysates was done by comparing peak areas obtained with a Star chromatographic analysis system (Varian Inc.) to external standards.

2.11. Statistical analysis

Dialysate dopamine and ethanol concentrations were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures. For the NOR-BNI/ U50488H experiments, the average of the three basal samples served as the baseline dopamine response to which the six U50488H samples were compared. For the ethanol self-administration experiments, the six home cage samples served as the baseline response to which the transfer and wait samples were compared. The average of the wait period (3 samples), including the last wait sample that encompassed the lever-press period, defined the baseline response to which the drink and post-drink samples were compared. The lever-press period was included as a basal sample because of its short duration. Any potential dopamine activity resulting from this period would be collected in the next sample due to the brief time lag inherent in microdialysis. ANOVA did not indicate a difference between the lever press period and the two previous wait samples (p > 0.05). Technical problems associated with sample collection or HPLC analysis resulted in the loss of 5 of 405 samples. To account for this we estimated these values by averaging adjacent time points and then adjusting the degrees of freedom in the ANOVA. Separate ANOVA tests were conducted to test for group by time interactions during the main phases of the experiment (e.g., basal plus transfer/wait period; wait period plus drink and post-drink periods). After determining a main effect during the drink period, further ANOVA tests were performed on individual points within the drink period (e.g., wait plus 1st drink sample). Post-hoc contrasts comparing individual time points to baseline within groups were performed after determining a significant group by time interaction during these periods. Bonferroni corrections were used in the case of post-hoc contrasts and ANOVA tests on individual points. ANOVA was performed using the Manova routine in SPSS for Windows, and post-hoc contrasts were performed using repeated measures in the GLM procedure. Regression analyses were carried out in EXCEL. Significance for all analyses was determined when p < 0.05. The area-under-curve was calculated by summing the values for dopamine and ethanol concentrations, respectively. Analysis of the consumption parameters was carried out using multivariate ANOVA (GLM procedure) and F-values derived from Wilks’ Lambda.

3. Results

3.1. Histological analysis and calcium-dependence of dopamine concentrations

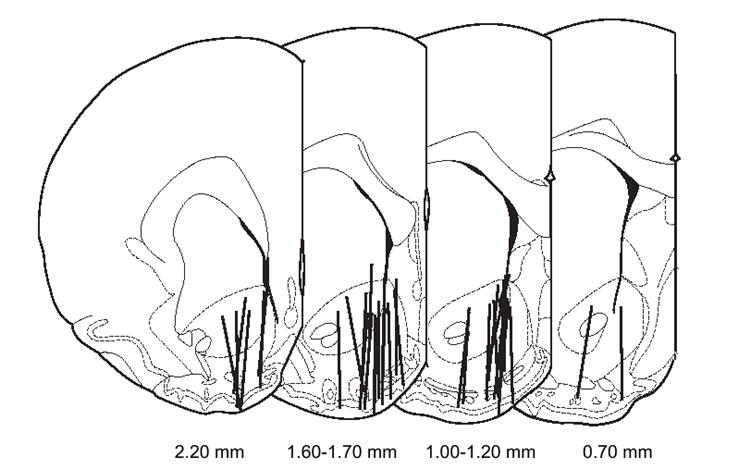

Each probe contained at least 55% of the active dialysis membrane within the nucleus accumbens. Examination of the probe positions within subregions of the accumbens showed that, overall, 34% were in the shell, 3% were in the core, and 63% bisected both the core and shell (Fig. 1). The core and shell subregions were not examined with regard to differences in dopaminergic function due to the dispersion of the probes between the groups. The dialysate dopamine samples showed excellent calcium dependence (91 ± 1% for the 35 subjects) and exceeded 71% in all subjects.

Fig. 1.

Coronal brain sections indicating microdialysis probe placement within the nucleus accumbens. Lines denote the active dialysis regions. Numerals below the sections denote the position of the slice in relation to Bregma. Figure was adapted fromPaxinos and Watson (1998).

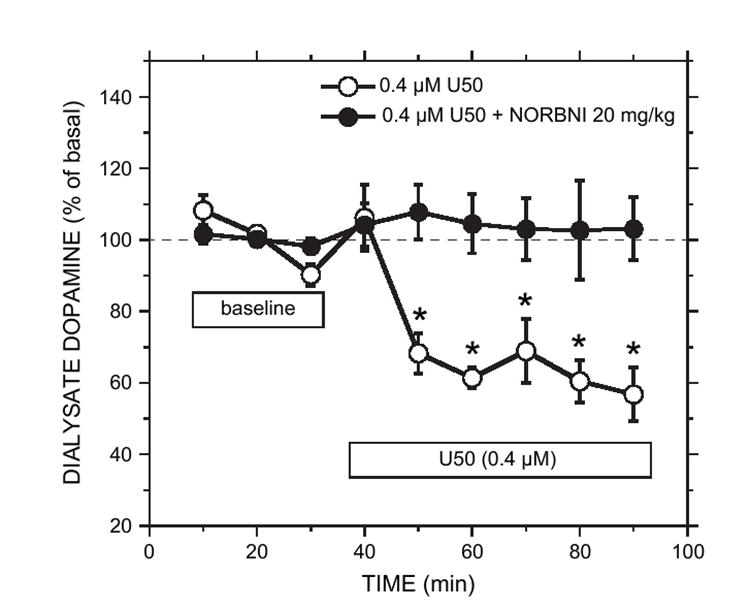

3.2. NOR-BNI blockade of U50488H

To confirm that the dose of NOR-BNI resulted in KOPr blockade, we tested the ability of the antagonist to block U50488H-induced suppression of accumbal dopamine activity (Heijna et al., 1990; Xi et al., 1998). Pretreatment with NOR-BNI (20 mg/kg, s.c.) 15–20 h prior to the experiment did not significantly alter basal dopamine levels in the accumbens (1.8 ± 0.4 nM; n = 4) compared to saline controls (1.3 ± 0.3 nM; n = 4). ANOVA showed no group effect [F(1,6) = 1.56, p > 0.05] or group by time effect [F(2,12) = 3.15, p > 0.05]. Within 20 min of perfusion through the dialysis probe, U50488H (0.4 or 1.6 μM) decreased dopamine concentrations by approximately 30% of their basal levels in the control group (time: F(6,18) = 19.39, p < 0.05; n = 4;Fig. 2). The effect of 0.4 μM U50488H was blocked in NOR-BNI pretreated animals [time: F(6,18) = 0.37, p > 0.05; n = 4;Fig. 2].

Fig. 2.

Effect of NOR-BNI pretreatment (20 mg/kg) on U50488H-induced suppression of basal dopamine concentration in the nucleus accumbens. NOR-BNI pretreatment occurred 15–20 h prior to the experiment. Microdialysis perfusion of the accumbens with U50488H (0.4 μM) reduced basal dopamine levels in the control group. NOR-BNI pretreatment effectively blocked this effect. The U50 (0.4 μM) group showed a significant effect of time (p < 0.05), denoted by the asterisks, whereas the U50 (0.4 μM) group pretreated with NOR-BNI did not. Each point represents the mean ± sem (n = 4 for each group).

3.3. Dopamine concentrations and operant behavior prior to ethanol access

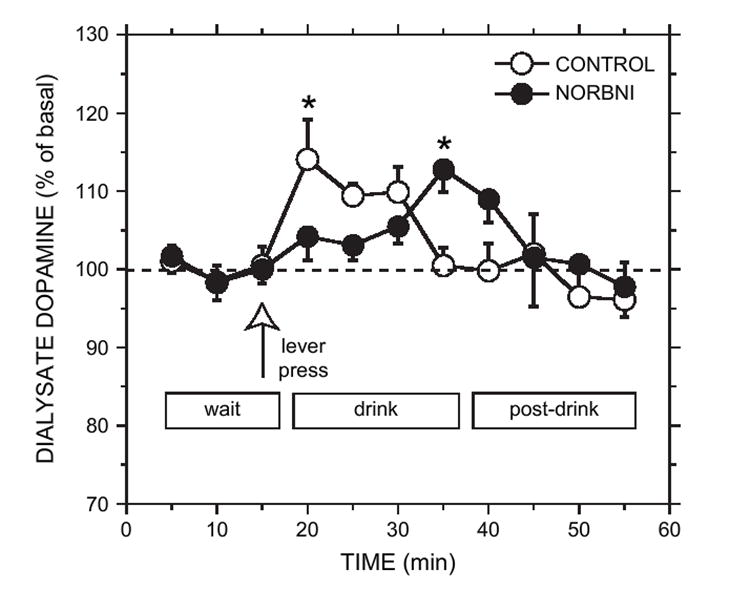

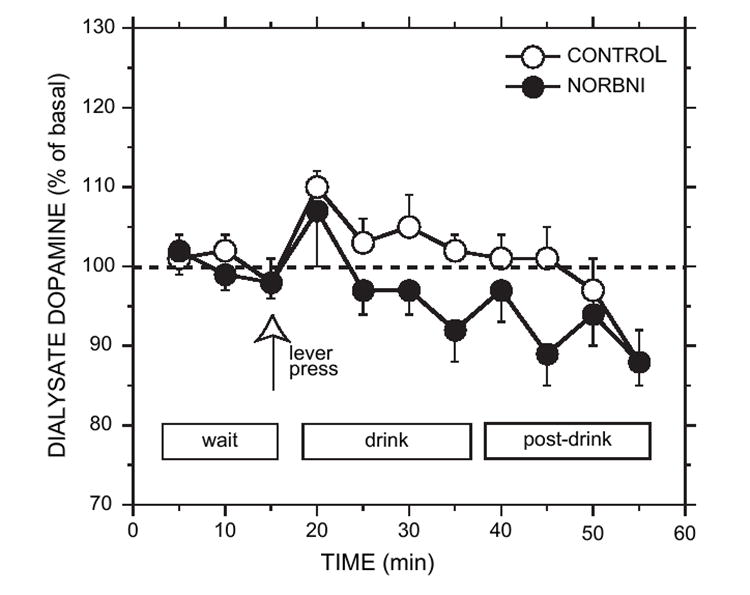

Pretreatment with NOR-BNI (20 mg/kg, s.c.) 15–20 h prior to the experiment did not affect basal dopamine concentrations in the home cage [NOR-BNI group (n = 7): 1.8 ± 0.4 nM; control group (n = 8): 2.3 ± 0.5 nM]. No significant group effect [F(1,13) = 0.24, p > 0.05] or group by time effect [F(5,65) = 0.99, p > 0.05] was observed during this period. Both groups showed an elevation in dopamine concentration after being transferred into the operant chamber [time: F(4,52) = 10.59, p < 0.05]. Due to the non-specific increase in dopamine concentration following the home-cage baseline period, we used the three dopamine samples from the wait period as a baseline for the subsequent analysis of the drink and post-drink periods. Both groups showed stable and similar mean dialysate dopamine concentrations (NOR-BNI: 2.0 ± 0.4 nM; control: 2.4 ± 0.5 nM) during the wait period [group: F(1,13) = 0.28, p > 0.05; group × time: F(2,26) = 0.03, p > 0.05;Fig. 3].

Fig. 3.

Effect of NOR-BNI (20 mg/kg) or saline (CONTROL) pretreatment on extracellular accumbal dopamine concentration during operant self-administration of 10% ethanol (plus 10% sucrose). Wait refers to the time in which the rat was in the operant chamber prior to access of the drinking solution. Lever press (open arrow) is the time at which operant responding occurred. Drink refers to the 20-min ethanol access period free of operant responding. Post-drink refers to the 20-min period in which the rat remained in the chamber in the absence of the ethanol solution. Dopamine concentration increased significantly within 5 min of ethanol access for the CONTROL group and returned to basal levels thereafter. The NOR-BNI group displayed no change in dopamine concentration initially, followed by a transient elevation at the end of the drink period. Each point represents the mean ± sem (n = 8 for the saline control group; n = 7 for the NOR-BNI group). Asterisk denotes significance compared with the wait period by post hoc simple contrasts (p < 0.05).

ANOVA indicated that the NOR-BNI-treated group (0.7 ± 0.3 min) did not differ significantly from the control group (0.6 ± 0.2 min) in terms of the time required to complete the operant response prior to ethanol consumption [F(1,13) = 0.13, p > 0.05; lever-pressing time;Table 2].

Table 2.

Lickometer parameters for the NOR-BNI and control groups during operant ethanol self-administration

| Parameter | NOR-BNI n = 7 | Control n = 8 |

|---|---|---|

| Lever-pressing time (min) | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 0.6 ± 0.2 |

| Latency to begin drinking (min) | 0.12 ± 0.05 | 0.05 ± 0.01 |

| Number of bouts | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 1.5 ± 0.2 |

| Initial bout duration (min) | 4.8 ± 1.2 | 5.8 ± 0.9 |

| Total licks | 1321 ± 253 | 1541 ± 288 |

| Licks during initial bout | 1164 ± 257 | 1457 ± 299 |

| Initial bout response rate (licks/min) | 257 ± 28 | 244 ± 30 |

| Response rate for ½ of initial bout (licks/min) | 266 ± 38 | 326 ± 37 |

Bout refers to a period of at least 25 licks, with no more than 2 min between licks. Values shown as mean ± sem.

3.4. Drinking behavior and dopamine concentrations following ethanol access

Both ethanol-drinking groups ingested similar amounts of 10% ethanol (plus 10% sucrose) during the dialysis experiment [NOR-BNI (n = 7): 1.5 ± 0.3 g/kg; control (n = 8): 1.8 ± 0.3 g/kg]. The mean fluid intake during the 20-min drink period was also similar between the groups (control: 8.9 ± 1.5 ml; NOR-BNI: 7.2 ± 1.2 ml).

The NOR-BNI and control groups displayed distinct dopamine time courses following ethanol (plus sucrose) access (Fig. 3). There was a significant group by time interaction across the drink period [F(4,50) = 6.13, p < 0.05]. Further between-group analyses of each point within the drink period indicated that the groups only differed during the fourth drink sample [group × time: F(1,11) = 10.99, p < 0.05]. In control (saline-treated) rats, dopamine concentration were significantly elevated in the first sample of the drink period (14 ± 5%) compared to baseline [F(1,101) = 9.79, p < 0.05] and returned to basal levels by the end of the 20-min drink period (Fig. 3). For NOR-BNI-treated rats, an alteration in dopamine concentration was not revealed during the first drink sample. However, within-group contrasts indicated that a small, but significant increase in dopamine levels (13 ± 3% above baseline) occurred during the fourth sample of the drink period [F(1,101) = 7.58, p < 0.05;Fig. 3].

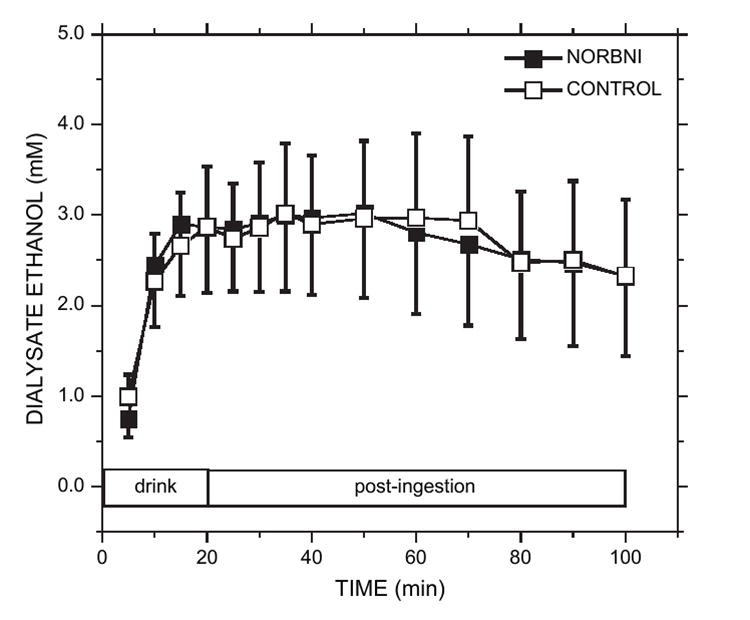

3.5. Accumbal ethanol concentrations following ethanol access

A quantifiable concentration of ethanol appeared in the dialysates within 5 min of ethanol access in all rats and the mean ethanol concentration in each sample increased thereafter (Fig. 4). The ethanol time courses did not significantly differ between the two treatment groups [group: F(1,13) = 0.02, p > 0.05; group × time: F(9,116) = 0.19, p > 0.05]. The mean dialysate ethanol levels reached peak concentrations (approximately 3 mM) 15 min after drinking commenced in both groups. Regression tests showed that both groups displayed significant and positive correlations between: (1) intake (g/kg) and dialysate ethanol area-under-curve (p < 0.05); and (2) intake (g/kg) and peak dialysate ethanol concentration (p < 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Dialysate ethanol concentrations (mM) from the nucleus accumbens following ethanol access for the NOR-BNI and saline CONTROL groups. Ethanol was analyzed from the same samples in which dopamine concentrations were measured. Both treatment groups showed very comparable ethanol pharmacokinetics. Peak dialysate ethanol levels were reached after the third sample of the drinking period. Each point is the mean ± sem.

3.6. Licking behavior during ethanol consumption

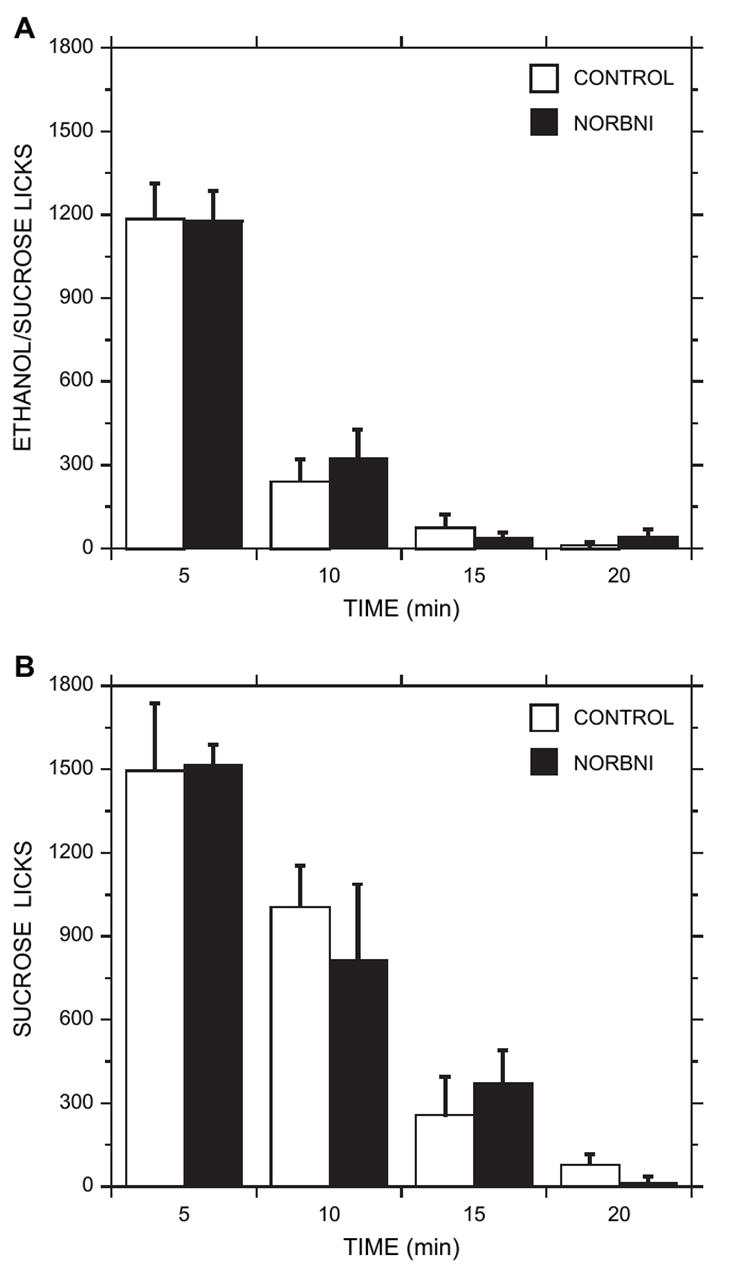

NOR-BNI treatment (20 mg/kg, s.c.) did not significantly alter licking behavior. Multivariate [group: F(9,5) = 0.53, p > 0.05] and univariate analyses (p > 0.05) revealed no group differences between the NOR-BNI and control groups with respect to several behavioral parameters (Table 2). Ethanol consumption in both groups began almost immediately after completion of the operant response (latency to begin drinking: 0.08 ± 0.02 min). The majority of consumption (licks) occurred during the first bout (91 ± 3% for the two groups).Fig. 5A illustrates the average number of spout licks within each 5-min interval of the drink period for each treatment. The NOR-BNI group ingested 92 ± 5% of total intake within 10 min of the ethanol access period and the control group ingested 99 ± 1% of total intake within this period.

Fig. 5.

Ethanol/sucrose (panel A) and sucrose (panel B) consumption (spout licks) during each 5-min interval of the 20-min ethanol access period. CONTROL and NOR-BNI-treated animals showed very similar patterns of ingestion across all periods. The majority of ethanol/sucrose or sucrose consumption occurred within the first 5–10 min. Each plot is the mean ± sem.

3.7. Dose-effect relationships between brain ethanol levels and dopamine response

Dialysate ethanol levels (area-under-curve; AUC) correlated positively with dialysate dopamine levels (AUC) during the drink period [F(1,5) = 14.05, p < 0.05; r = 0.86] for the NOR-BNI group, but not for the control group [F(1,6) = 0.25, p > 0.05; r = 0.20]. Because the NOR-BNI group showed a significant dopamine response at the end of the 20-min drink period, when ethanol concentration peaked we also examined the relationship between dopamine and ethanol concentrations during the last two samples of the drink period. Regression analysis revealed a significant and positive correlation between dialysate ethanol levels (AUC) and dialysate dopamine levels (AUC) during this period for the NOR-BNI group [F(1,5) = 10.31, r = 0.82; p < 0.05]. The control group showed no significant correlations during the drink period.

3.8. Drinking behavior and dopamine concentrations following sucrose access

To assess whether the dopamine response in the NOR-BNI-treated ethanol group was related to the presence of sucrose in the drinking solution, an additional set of rats was trained to self-administer a 10% sucrose solution that did not contain ethanol. These animals received NOR-BNI (0 or 20 mg/kg) 15–20 h prior to the experiment. Mean sucrose intake during testing was very similar between the groups [NOR-BNI (n = 6): 13 ± 2 ml; control (n = 6): 14 ± 1 ml], as were the mean number of spout licks within each 5-min interval of the drink period (Fig. 5B). The NOR-BNI group ingested 84 ± 6% of total intake within 10 min of sucrose access and the control group ingested 90 ± 4% of total intake within this period.

Mean home-cage basal dopamine concentrations were 3.5 ± 0.4 nM for the NOR-BNI group; 2.4 ± 0.5 nM for the saline control group, and 4.1 ± 0.5 nM and 2.6 ± 0.6 nM, respectively, during the wait period. ANOVA revealed a significant effect of group during the home-cage baseline [F(1,11) = 4.96, p < 0.05] and wait periods [F(1,11) = 6.19, p < 0.05], but not a significant time [F(2,22) = 6.03, p > 0.05] or group by time effect [F(2,22) = 0.57, p > 0.05] during these periods. Due to the apparent discrepancy in basal dopamine levels between the sucrose groups and the two previous sets of animals that were treated with NOR-BNI, we performed a cumulative analysis of basal dopamine concentrations, comparing all NOR-BNI-treated rats with all saline-treated control rats. However, the two groups were not different [group: F(1,33) = 0.71, p > 0.05; group × time: F(2,66) = 0.21, p > 0.05]. Further analysis of the sucrose-drinking animals indicated that dopamine levels were not significantly different between the NOR-BNI and salinetreated groups during the sucrose-access period [group × time: F(4,40) = 1.10, p > 0.05;Fig. 6].

Fig. 6.

Effect of NOR-BNI (20 mg/kg) or saline (CONTROL) pretreatment on extracellular accumbal dopamine concentration during operant self-administration of 10% sucrose. Wait refers to the time in which the rat was in the operant chamber prior to access of the drinking solution. Lever press (open arrow) is the time at which operant responding occurred. Drink refers to the 20-min ethanol access period free of operant responding. Post-drink refers to the 20-min period in which the rat remained in the chamber in the absence of the ethanol solution. Dopamine concentrations during the drink and post-drink periods were not significantly different from basal levels in either group (p > 0.05). Each point represents the mean ± sem (n = 6 for each group).

4. Discussion

These present findings demonstrate that blockade of the KOPr with NOR-BNI resulted in a latent increase in accumbal dopamine concentration following ethanol access, which showed a positive correlation with brain ethanol levels. Despite this alteration in dopamine activity, NOR-BNI did not significantly alter operant responding or consumption of 10% ethanol (plus 10% sucrose). The NOR-BNI treatment effectively blocked the reduction of accumbal dopamine levels by the κ-opioid agonist, U50488H, indicating that the NOR-BNI treatment regimen employed resulted in the blockade of the KOPr.

The NOR-BNI and saline control rats displayed similar appetitive responses (as measured by lever-response time and latency to begin licking), indicating that KOPr blockade did not alter the performance of the operant behavior. NOR-BNI (20 mg/kg) did not affect ethanol intake or any consumption parameters measured. These results are in line with previous work that showed no effect of lower doses of NOR-BNI on operant ethanol reinforcement (Williams and Woods, 1998; Holter et al., 2000). Importantly, however, the finding that the NOR-BNI dose used in the present study prevented the dopamine response to an exogenous KOPr agonist shows that the lack of effect cannot be attributed to an insufficient dose of the antagonist. Ethanol intake during the access period (about 1.5–1.8 g/kg in 20 min), and presumably brain ethanol levels, were considerably higher than that reported in the two previous studies within a comparable access time (1–3 h) (Williams and Woods, 1998; Holter et al., 2000). Therefore, the present results extend the previous findings and further suggest that the endogenous KOPr system is not involved in operant responding or subsequent consumption even under conditions in which brain levels of ethanol are more likely to produce a pharmacological response.

Control (saline-treated) rats exhibited a small and transient increase in dopamine concentration during ethanol (plus sucrose) consumption, followed by a rapid decline to basal levels. The increase occurred at a time when accumbal dialysate ethanol levels were low (1.0 ± 0.3 mM) relative to peak concentration (3.0 ± 0.8 mM). This finding supports past results (Doyon et al., 2003, 2005) and further demonstrates that the initial phase of ethanol consumption can induce a temporary elevation in accumbal dopamine activity. This increase does not correspond to peak accumbal ethanol levels, suggesting that it may not reflect a direct pharmacological response to ethanol. Doyon et al. (2005)hypothesized that the brief increase in dopamine concentration during the initial phase of ethanol drinking was due to the stimulus properties of ethanol and that these sensory cues were strongest during ingestion, which is also in accordance with the present findings. It is unlikely that the transient dopamine activity was the result of overflow from the operant response period or ethanol anticipation since dopamine stimulation did not occur during operant self-administration of a novel sucrose solution in rats conditioned to drink ethanol as shown byDoyon et al. (2005).

NOR-BNI treatment resulted in a latent increase in dopamine concentration during ethanol self-administration compared to the control group. The enhanced dopamine response was brief and occurred as brain ethanol concentrations reached peak levels (15–20 min following the initiation of ethanol consumption). During this period, accumbal dopamine levels correlated positively with ethanol concentrations, suggesting that the increase was a pharmacological response to the drug. This effect was specific to the NOR-BNI group, as a similar relationship was not revealed at any point during the ethanol-access period in controls. Our original hypothesis was that ethanol administration elicits the release of endogenous dynorphin peptides and the resultant increase in KOPr activation inhibits dopamine release. The increase in dopamine during the latter phase of the consumption period is consistent with this possibility. Thus, KOPr blockade may have briefly uncovered an increase in accumbal dopamine activity that is normally suppressed by ethanol-induced dynorphin release (Marinelli et al., 2005). Indeed, consistent with this hypothesis, a recent study (Zapata and Shippenberg, 2006) has shown that pharmacological or genetic inactivation of the KOPr potentiates the dopamine response to i.p. ethanol administration. Our results extend this work by suggesting that the κ-opioid system may counter the stimulatory effects of ethanol on dopamine concentrations following operant ethanol self-administration.

The duration of the NOR-BNI-induced dopamine response during ethanol self-administration was not as long as expected, when considering that NOR-BNI is a long-acting kappa antagonist and that brain ethanol levels remained elevated far beyond the period in which the increase occurred. These results may reflect a rapid adaptive response within the mesolimbic system to the interaction of the KOPr with ethanol. Previous studies clearly demonstrate that intra-accumbal dopamine and ethanol time courses dissociate rapidly following i.p. or oral ethanol administration (Yim et al., 2000; Doyon et al., 2005). Therefore, it appears likely that other mechanisms, in addition to the κ-opioid system, regulate ethanol-induced dopamine activity. Interestingly, however, there is evidence that stimulation of accumbal dynorphin release by ethanol is transient and occurs only within 30 min of ethanol administration (Marinelli et al., 2005), which is consistent with the time course of the NOR-BNI effect in the present study. These data suggest that further dopaminergic activation would not have occurred regardless of KOPr blockade and the presence of ethanol.

Clearly, an overarching issue with these results is understanding the functional significance of these subtle dopaminergic changes since NOR-BNI did not alter behavior during ethanol reinforcement. The duration of the neurochemical changes and their magnitude over time could potentially have a latent influence over behavior. It was recently reported that ethanol consumption increased in a continuous-access drinking paradigm after long-term KOPr blockade with NOR-BNI (Mitchell et al., 2005), suggesting that the duration of KOPr blockade, the experimental paradigm employed, or rat strain may be critical factors that influence the effect of KOPr blockade on ethanol drinking behavior. However, it is also possible that these dopaminergic alterations have no impact on ethanol seeking behavior that is already established and under the regulatory control of other local circuit mechanisms. In this case, further study is needed in which NOR-BNI is administered to ethanol naive animals prior to the initiation of self-administration training.

One aspect of the dopamine profile observed under NOR-BNI blockade that is difficult to explain is the apparent absence of the transient dopamine activity during the initial 5 min of ethanol access exhibited by controls. The within-group comparison of the first point taken after drinking to the pre-drinking baseline in the NOR-BNI-treated group supports this contention. In contrast, between-group comparisons indicated that the dopamine response in the NOR-BNI group was lower, but not significantly different, from controls during the first sample taken after consumption began. Therefore, one must be cautious before concluding that kappa blockade inhibited the transient dopamine response associated with ethanol consumption. It is possible that this effect is mediated by the blockade of κ-opioid receptors located on non-dopaminergic neurons. For example, Shoji et al. (1999)reported that activation of the KOPr inhibits GABAb-mediated inhibitory potentials on ventral tegmental dopamine neurons. These interactions could be mediated by neuronal pathways that are specifically activated by stimulus input (e.g., ethanol cues) and functionally independent from those involved in the latent, possibly pharmacological, dopamine response. An examination of the local effects of NOR-BNI within the ventral tegmental area or nucleus accumbens during ethanol self-administration may help clarify this issue. If NOR-BNI altered the transient dopamine response to ethanol, it could be construed as evidence that NOR-BNI affected the discriminative stimulus properties of ethanol. A previous study suggests that NOR-BNI does not act in this manner (Spanagel, 1996), however, this work employed a distinct operant paradigm with considerably different experimental conditions, which could lead to different interpretations of this point.

NOR-BNI did not alter dopamine activity during sucrose self-administration, which strongly suggests that the latent dopamine response observed during ethanol consumption is specific to ethanol and not related to the presence of sucrose in the solution. The absence of a dopamine response in sucrose-drinking controls is consistent with past results in non-deprived animals (Roitman et al., 2004; Doyon et al., 2005). We previously reported that dopamine levels in control animals, however, are elevated briefly during sucrose consumption using a fixed-ratio 24 schedule of responding (Doyon et al., 2004). This discrepancy is likely due to the different training schedules and response requirements that were used between the studies. For example, the duration of the response requirement may influence the timing or expectancy involved in acquiring the sucrose solution, which mesoaccumbens dopamine activity could code for differentially. Phasic changes in dopamine neuron firing have been linked with the probability and uncertainty involved in reward acquisition (Fiorillo et al., 2003).

The lack of effect of NOR-BNI on sucrose consumption contrasts with an early study in non-deprived animals that demonstrated a reduction in consumption after acute NOR-BNI administration in a non-operant paradigm (Beczkowska et al., 1992). One major difference between the studies is that we administered NOR-BNI 15–20 h prior to testing, whereas the experiments in the latter study were performed after a 1-h pretreatment period. Others have suggested that NOR-BNI is a slow onset κ-opioid antagonist that may have non-selective action after acute administration (Endoh et al., 1992; Williams and Woods, 1998), which may explain the apparent discrepancy.

NOR-BNI did not significantly affect basal dialysate dopamine concentrations. Although the sucrose group treated with NOR-BNI showed elevated basal dopamine values, an analysis of all NOR-BNI-treated subjects revealed no overall difference compared to the control groups. This finding is in accord with work by Chefer et al. (2005)that compared differences in basal dopamine activity during initial (4 h) versus more prolonged KOPr (24 h) blockade. Previous work has shown that NOR-BNI can increase basal dopamine levels in the accumbens within 40 min of administration (Spanagel et al., 1992; Maisonneuve et al., 1994), but the effect is short-lived and not characteristic of a long-acting antagonist. Chefer et al. (2005)has suggested that dopamine release is in fact enhanced after long-term kappa blockade with NOR-BNI, but that basal dopamine concentration remains unchanged due to an increase in dopamine uptake. Thus, the KOPr system may interact with the dopamine transporter to regulate basal dopamine levels, a possibility supported by their anatomical localization (Svingos et al., 2001). How this interaction may affect dopamine dynamics during ethanol self-administration, however, is unknown at present.

In summary, these findings demonstrate that blockade of the KOPr with NOR-BNI resulted in a latent increase in accumbal dopamine concentration following ethanol access, which correlated with brain ethanol levels and is consistent with a direct pharmacological effect. NOR-BNI did not alter dopamine concentration in rats self-administering 10% sucrose, suggesting an ethanol-specific effect. Blockade of the KOPr with NOR-BNI may have temporarily disinhibited accumbal dopamine activity that is normally suppressed by ethanol-induced dynorphin release. NOR-BNI did not significantly affect operant responding or consumption of 10% ethanol (plus 10% sucrose) or 10% sucrose alone. In view of the absence of behavioral changes with NOR-BNI, the functional significance of the dopaminergic alterations during ethanol self-administration remains uncertain. A more complete interpretation of this work requires further understanding of the precise mechanisms involved in KOPr regulation of mesoaccumbens dopamine activity and ethanol seeking behavior.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Richard Wilcox for helpful discussions regarding the statistical analyses and Chi-Chun Wu, Angela Bird, and Christina Schier for excellent assistance with the histology and animal training. This work was funded by grants from NIAAA (AA11852) and (AA U01 13486-INIA project). WMD was supported by a training grant from NIAAA (5F31AA014849-02).

References

- Bals-Kubik R, Ableitner A, Herz A, Shippenberg TS. Neuroanatomical sites mediating the motivational effects of opioids as mapped by the conditioned place preference paradigm in rats. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1993;264:489–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beczkowska IW, Bowen WD, Bodnar RJ. Central opioid receptor subtype antagonists differentially alter sucrose and deprivation-induced water intake in rats. Brain Research. 1992;589:291–301. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91289-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chefer VI, Czyzyk T, Bolan EA, Moron J, Pintar JE, Shippenberg TS. Endogenous kappa-opioid receptor systems regulate mesoaccumbal dopamine dynamics and vulnerability to cocaine. Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25:5029–5037. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0854-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark JA, Pasternak GW. U50,488: a kappa-selective agent with poor affinity for mu1 opiate binding sites. Neuropharmacology. 1988;27:331–332. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(88)90052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowen MS, Lawrence AJ. The role of opioid-dopamine interactions in the induction and maintenance of ethanol consumption. Progress in Neuro-psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 1999;23:1171–1212. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(99)00060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czachowski CL, Chappell AM, Samson HH. Effects of raclopride in the nucleus accumbens on ethanol seeking and consumption. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2001;25:1431–1440. doi: 10.1097/00000374-200110000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine DP, Leone P, Pocock D, Wise RA. Differential involvement of ventral tegmental mu, delta and kappa opioid receptors in modulation of basal mesolimbic dopamine release: in vivo microdialysis studies. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1993;266:1236–1246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyon WM, York JL, Diaz LM, Samson HH, Czachowski CL, Gonzales RA. Dopamine activity in the nucleus accumbens during consummatory phases of oral ethanol self-administration. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;27:1573–1582. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000089959.66222.B8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyon WM, Ramachandra V, Samson HH, Czachowski CL, Gonzales RA. Accumbal dopamine concentration during operant self-administration of a sucrose or a novel sucrose with ethanol solution. Alcohol. 2004;34:261–271. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyon WM, Anders SK, Ramachandra VS, Czachowski CL, Gonzales RA. Effect of operant self-administration of 10% ethanol plus 10% sucrose on dopamine and ethanol concentrations in the nucleus accumbens. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2005;93:1469–1481. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endoh T, Matsuura H, Tanaka C, Nagase H. Nor-binaltorphimine: a potent and selective kappa-opioid receptor antagonist with long-lasting activity in vivo. Archives Internationales de Pharmacodynamie et de Therapie. 1992;316:30–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorillo CD, Tobler PN, Schultz W. Discrete coding of reward probability and uncertainty by dopamine neurons. Science. 2003;299:1898–1902. doi: 10.1126/science.1077349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales RA, Weiss F. Suppression of ethanol-reinforced behavior by naltrexone is associated with attenuation of the ethanol-induced increase in dialysate dopamine levels in the nucleus accumbens. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:10663–10671. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-24-10663.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heijna MH, Padt M, Hogenboom F, Portoghese PS, Mulder AH, Schoffelmeer AN. Opioid receptor-mediated inhibition of dopamine and acetylcholine release from slices of rat nucleus accumbens, olfactory tubercle and frontal cortex. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1990;181:267–278. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(90)90088-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herz A. Endogenous opioid systems and alcohol addiction. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1997;129:99–111. doi: 10.1007/s002130050169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge CW, Samson HH, Chappelle AM. Alcohol self-administration: further examination of the role of dopamine receptors in the nucleus accumbens. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1997;21:1083–1091. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1997.tb04257.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holter SM, Henniger MS, Lipkowski AW, Spanagel R. Kappa-opioid receptors and relapse-like drinking in long-term ethanolexperienced rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000;153:93–102. doi: 10.1007/s002130000601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyytia P, Kiianmaa K. Suppression of ethanol responding by centrally administered CTOP and naltrindole in AA and Wistar rats. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2001;25:25–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2001.tb02123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikemoto S, McBride WJ, Murphy JM, Lumeng L, Li TK. 6-OHDA-lesions of the nucleus accumbens disrupt the acquisition but not the maintenance of ethanol consumption in the alcohol-preferring p line of rats. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1997;21:1042–1046. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone P, Pocock D, Wise RA. Morphine-dopamine interaction: ventral tegmental morphine increases nucleus accumbens dopamine release. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 1991;39:469–472. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(91)90210-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindholm S, Ploj K, Franck J, Nylander I. Repeated ethanol administration induces short- and long-term changes in enkephalin and dynorphin tissue concentrations in rat brain. Alcohol. 2000;22:165–171. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(00)00118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindholm S, Werme M, Brene S, Franck J. The selective kappa-opioid receptor agonist U50,488H attenuates voluntary ethanol intake in the rat. Behavorial Brain Research. 2001;120:137–146. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00368-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisonneuve IM, Archer S, Glick SD. U50,488, a kappa opioid receptor agonist, attenuates cocaine-induced increases in extracellular dopamine in the nucleus accumbens of rats. Neuroscience Letters. 1994;181:57–60. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90559-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis EB, Hjelmstad GO, Bonci A, Fields HL. Kappa-opioid agonists directly inhibit midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23:9981–9986. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-31-09981.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinelli PW, Bai L, Quirion R, Gianoulakis C. A microdialysis profile of dynorphin release in the rat nucleus accumbens following alcohol administration. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29:10A. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000183008.62955.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello NK, Negus SS. Effects of kappa opioid agonists on cocaine and food-maintained responding by rhesus monkeys. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1998;286:812–824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JM, Liang MT, Fields HL. A single injection of the kappa opioid antagonist norbinaltorphimine increases ethanol consumption in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;182:384–392. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0067-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mucha RF, Herz A. Motivational properties of kappa and mu opioid receptor agonists studied with place and taste preference conditioning. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1985;86:274–280. doi: 10.1007/BF00432213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nader K, van der Kooy D. Deprivation state switches the neurobiological substrates mediating opiate reward in the ventral tegmental area. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:383–390. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-01-00383.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Fourth ed. Academic Press; San Diego: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit HO, Justice JB., Jr . Procedures for microdialysis with smallbore HPLC. In: Robinson TE, Justice JB Jr, editors. Microdialysis in the Neurosciences. Vol. 7. Elsevier; New York: 1991. pp. 117–153. [Google Scholar]

- Rassnick S, Pulvirenti L, Koob GF. Oral ethanol self-administration in rats is reduced by the administration of dopamine and glutamate receptor antagonists into the nucleus accumbens. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1992;109:92–98. doi: 10.1007/BF02245485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AJ, McDonald JS, Heyser CJ, Kieffer BL, Matthes HW, Koob GF, Gold LH. mu-Opioid receptor knockout mice do not self-administer alcohol. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2000;293:1002–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roitman MF, Stuber GD, Phillips PE, Wightman RM, Carelli RM. Dopamine operates as a subsecond modulator of food seeking. Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24:1265–1271. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3823-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosin A, Lindholm S, Franck J, Georgieva J. Downregulation of kappa opioid receptor mRNA levels by chronic ethanol and repetitive cocaine in rat ventral tegmentum and nucleus accumbens. Neuroscience Letters. 1999;275:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00675-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson HH. Initiation of ethanol reinforcement using a sucrosesubstitution procedure in food- and water-sated rats. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1986;10:436–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1986.tb05120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson HH, Hodge CW, Tolliver G, Haraguchi M. Effect of dopamine agonists and antagonists on ethanol-reinforced behavior: the involvement of the nucleus accumbens. Brain Research Bulletin. 1993;30:133–141. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(93)90049-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoji Y, Delfs J, Williams JT. Presynaptic inhibition of GABAB-mediated synaptic potential in the ventral tegmental area during morphine withdrawal. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19:2347–2355. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-06-02347.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanagel R. The influence of opioid antagonists on the discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 1996;54:645–649. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(95)02288-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanagel R, Herz A, Shippenberg TS. Opposing tonically active endogenous opioid systems modulate the mesolimbic dopaminergic pathway. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1992;89:2046–2050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svingos AL, Chavkin C, Colago EE, Pickel VM. Major coexpression of kappa-opioid receptors and the dopamine transporter in nucleus accumbens axonal profiles. Synapse. 2001;42:185–192. doi: 10.1002/syn.10005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takemori AE, Ho BY, Naeseth JS, Portoghese PS. Nor-binaltorphimine, a highly selective kappa-opioid antagonist in analgesic and receptor binding assays. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1988;246:255–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KL, Woods JH. Oral ethanol-reinforced responding in rhesus monkeys: effects of opioid antagonists selective for the mu-, kappa-, or delta-receptor. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1998;22:1634–1639. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi ZX, Fuller SA, Stein EA. Dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens during heroin self-administration is modulated by kappa opioid receptors: an in vivo fast-cyclic voltammetry study. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1998;284:151–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yim HJ, Robinson DL, White ML, Jaworski JN, Randall PK, Lancaster FE, Gonzales RA. Dissociation between the time course of ethanol and extracellular dopamine concentrations in the nucleus accumbens after a single intraperitoneal injection. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:781–788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapata A, Shippenberg TS. Endogenous kappa opioid receptor systems modulate the responsiveness of mesoaccumbal dopamine neurons to ethanol. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2006;30:592–597. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]