Abstract

The nephron, the basic structural and functional unit of the vertebrate kidney, is organized into discrete segments, which are composed of distinct renal epithelial cell types. Each cell type carries out highly specific physiological functions to regulate fluid balance, osmolarity, and metabolic waste excretion. To date, the genetic basis of regionalization of the nephron has remained largely unknown. Here we show that Irx3, a member of the Iroquois (Irx) gene family, acts as a master regulator of intermediate tubule fate. Comparative studies in Xenopus and mouse have identified Irx1, Irx2, and Irx3 as an evolutionary conserved subset of Irx genes, whose expression represents the earliest manifestation of intermediate compartment patterning in the developing vertebrate nephron discovered to date. Intermediate tubule progenitors will give rise to epithelia of Henle’s loop in mammals. Loss-of-function studies indicate that irx1 and irx2 are dispensable, whereas irx3 is necessary for intermediate tubule formation in Xenopus. Furthermore, we demonstrate that misexpression of irx3 is sufficient to direct ectopic development of intermediate tubules in the Xenopus mesoderm. Taken together, irx3 is the first gene known to be necessary and sufficient to specify nephron segment fate in vivo.

Keywords: Irx, kidney organogenesis, nephron, segmentation, Xenopus, mouse

Vertebrate kidneys are organs of complex structure and function. They are derived from the intermediate mesoderm in a process involving inductive interactions, mesenchyme-to-epithelium transitions, and branching morphogenesis that ultimately leads to the development of a fully mature excretory organ composed of thousands of nephrons, which are the functional units of the kidney (Saxén 1987). Along the proximodistal axis, each nephron is organized into proximal tubule, intermediate tubule, and distal tubule, which will connect with the collecting duct system. Each tubule can be further subdivided into separate segments based on histological criteria (Kriz and Bankir 1988). The segments are composed of specialized epithelial cell types with unique functional properties, such as solute transport, pH regulation, and water absorption. Importantly, the segments do not operate independently but rely on the correct spatial organization along the nephron to insure normal excretory functions. Absence of specific tubular segments, such as the proximal convoluted tubules, has been observed in man and usually causes stillbirth or neonatal lethality (Allanson et al. 1992). In recent years, major insights into transcription factors and signaling pathways that control the early stages of nephrogenesis have been gained (Vainio and Lin 2002; Dressler 2006). In contrast, little is known about the processes that underlie the subsequent patterning and regionalization of the nephron.

Studies in Xenopus and mice have suggested a need for Notch signaling activity and the Notch effector HRT1/Hey1 in specifying proximal fates (McLaughlin et al. 2000; Cheng et al. 2003; Wang et al. 2003; Taelman et al. 2006). Recently, genetic analysis has revealed that Notch2 is required for the differentiation of podocytes and proximal convoluted tubules (Cheng et al. 2007). Furthermore, specification of proximal lineages also requires Lim1/Lhx1 gene function (Kobayashi et al. 2005), which may act as an upstream regulator of Notch signaling. Finally, survival of proximal tubular fates is dependent on FGF8 (Grieshammer et al. 2005). Far less is known how the more distal nephron segments are specified. Mouse embryos that lack Brn1 (Pou3f3), a POU domain transcription factor, initiate nephrogenesis but form truncated nephrons that lack the loop of Henle and distal tubules (Nakai et al. 2003). Whether Brn1 is sufficient to specify these nephron segments is not known.

The analysis of mammalian kidney organogenesis by targeted gene disruptions is time-consuming and frequently requires the generation of conditional mutant alleles. Furthermore, in the case of redundant gene functions, the generation of compound mutant animals is necessary. We therefore turned to an amphibian animal model, the Xenopus embryo, to determine whether it could serve as a simple, cost-effective model to study the molecular basis of nephron segmentation. The Xenopus embryo generates within 2 d after fertilization a simple excretory organ, the pronephric kidney, which is essential for the survival of the larvae (Brändli 1999). Importantly, pronephric development is regulated by many of the same genes necessary for nephrogenesis in mammals, including Wnt4 and FGF8 (Saulnier et al. 2002b; Urban et al. 2006). First evidence for segmental organization of the pronephric nephron was provided by histological analysis (Mobjerg et al. 2000), and has recently been supported by studies demonstrating regionalized expression of transporter and ion channel genes along the proximodistal axis (Eid et al. 2002; Zhou and Vize 2004).

Results

The basic segmental organization of the nephron is conserved between pronephric and metanephric kidneys

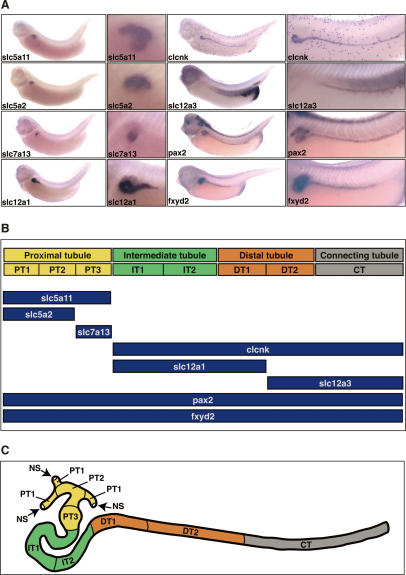

We performed an extensive analysis of solute carrier (Slc) gene expression during Xenopus embryogenesis to identify novel segment-specific marker genes whose patterns may establish a comprehensive model of the pronephric nephron segmentation (Fig. 1). Database searches led to the identification of Xenopus cDNAs encoding 210 slc gene family members, which were used for whole-mount in situ hybridization studies. A total of 91 slc genes showed pronephric expression, usually in highly regionalized patterns. Selected examples of slc genes are shown in Figure 1A. In contrast, pax2, an early pronephric marker gene (Heller and Brändli 1997), was expressed along the entire nephron. Slc gene expression patterns were carefully mapped along the mature pronephric nephron (Fig. 1B) and compared, where data was available, with the expression of the orthologous Slc genes in the adult mammalian kidney (Table 1). A full account of pronephric Slc gene expression, which will include marker genes for each nephron segment, will be presented elsewhere (D. Raciti, L. Reggiani, and A.W. Brändli, in prep.).

Figure 1.

Segmental organization of the Xenopus pronephric nephron. (A) Spatial expression patterns of selected pronephric marker genes. Xenopus embryos (stage 35/36) were stained by whole-mount in situ hybridization for expression of clcnk (ClC-K), fxyd2 (Na, K-ATPase γ subunit), pax2, slc5a2 (SGLT2), slc5a11 (SGLT1L), slc7a13, slc12a1 (NKCC2), and slc12a3 (NCC). Lateral views are shown with accompanying enlargements of the pronephric kidney region. (B) Summary of marker gene expression along the proximodistal axis of the pronephric nephron. The localization of the expression domains is shown below the corresponding segments. (C) Schematic representation of the tubular portion of the Xenopus pronephric kidney. A stage 35/36 pronephric kidney is shown with the four tubular compartments color-coded. Each tubule may be further subdivided into distinct segments: proximal tubule (yellow; PT1, PT2, PT3), intermediate tubule (green; IT1, IT2, IT3), distal tubule (orange; DT1, DT2), and connecting tubule (gray; CT). The nephrostomes (NS) are ciliated peritoneal funnels that connect the coelomic cavity to the nephron.

Table 1.

Selected segment-specific marker genes of the pro- and metanephric nephron

Note that only a single clcnk gene is known in Xenopus, whereas there are two mouse clcnk genes—clcnka and clcnkb. The expression of Xenopus clcnk in the intermediate, distal, and connecting tubules therefore has to be compared with the combined renal expression domains of mouse Clcnka and Clcnkb. See Figures 1 and 3 for abbreviations of Xenopus and mouse nephron segments, respectively.

(acc. no.) Accession number; (n.d.) not determined.

The segmental character of the pronephric nephron, which emerged from comparative gene expression studies, extends an older description (Zhou and Vize 2004) and demonstrates remarkable similarities with the organization of the mammalian metanephric nephron (Fig. 1B,C; Table 1). We therefore suggest, in line with the mammalian nomenclature (Kriz and Bankir 1988), that the pronephric nephron is composed of four basic domains: proximal tubule, intermediate tubule, distal tubule, and connecting tubule (CT, formerly known as pronephric duct). Each tubule may be further subdivided into distinct segments. For example, the proximal tubule is divided into three segments (PT1, PT2, and PT3), which share expression of many of the Slc genes characteristic for the S1, S2, and S3 segments of the mammalian proximal tubule (Fig. 1C). The CT has similarities at the gene expression level with the CT of the mammalian collecting duct system. A total of at least eight functionally distinct segments were defined. Taken together, the hallmarks of vertebrate nephron organization—the presence of distinct segmented tubular compartments—can be delineated already at the level of the Xenopus pronephric nephron.

Expression of an evolutionary conserved subset of Iroquois (Irx) genes during nephron development

The genes involved in regionalization and proximodistal patterning of the nephron are still poorly understood. Irx genes encode homeodomain-containing transcription factors, which spatially prepattern the neural system in vertebrates and invertebrates (Gomez-Skarmeta and Modolell 2002). Moreover, Irx genes have been implicated in the specification of heart chambers (Bao et al. 1999). Interestingly, some Irx genes are also expressed during vertebrate kidney development (Bellefroid et al. 1998; Houweling et al. 2001). Given this data, we hypothesized that Irx genes play a role in patterning the vertebrate nephron. To support this idea, we first performed a detailed analysis of the spatio-temporal expression during nephrogenesis in Xenopus and mouse. The genomes of both species contain six members of the Irx gene family organized into two clusters: IrxA (containing Irx1, Irx2, and Irx4) and IrxB (containing Irx3, Irx5, and Irx6) (Peters et al. 2000; de la Calle-Mustienes et al. 2005).

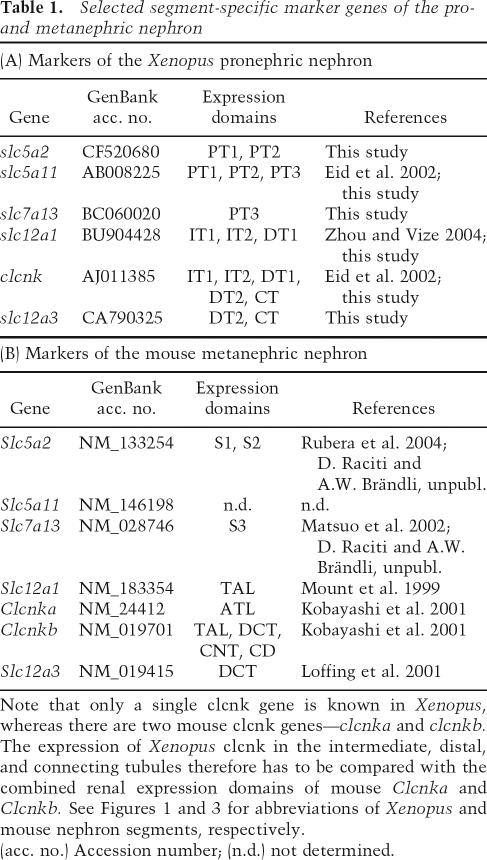

In Xenopus, pronephric kidney organogenesis is initiated during late gastrulation with the specification of the pronephric anlagen, and is completed by stage 37/38 (Brändli 1999). Expression of irx6 occurs late in Xenopus embryogenesis and is not associated with the developing pronephric kidney (de la Calle-Mustienes et al. 2005). Similarly, we failed to find any evidence for pronephric expression of irx4 and irx5 (L. Reggiani and A.W. Brändli, unpubl.; data not shown). In contrast, irx1, irx2, and irx3 were expressed during pronephric kidney development in highly characteristic patterns (Fig. 2; Supplementary Fig. 1). irx3 expression was initiated at stage 25 followed 8 h later at stage 29/30 by irx1 and irx2 (Fig. 2D; Supplementary Fig. 1). Interestingly, irx3 expression also preceded expression of segment-specific terminal differentiation markers such as slc5a11 (formerly SGLT-1L) and clnck (ClC-K) at stages 29/30 and 31, respectively (Eid et al. 2002; Vize 2003). While irx3 expression gradually ceased from stage 35/36 onward, irx1 and irx2 expression persisted in the pronephros (L. Reggiani and A.W. Brändli, unpubl.; data not shown). Most intriguingly, pronephric irx gene expression was highly regionalized and confined to a central region of the developing nephron (Fig. 2A–C). Mapping of the expression domains to distinct nephron segments of the stage 35/36 embryo revealed that irx1 and irx2 expression was confined to the intermediate tubule segment IT1, whereas irx3 was found in PT3, IT1, and IT2. Notably, sharp borders characterized the irx expression domains along the nephron. Taken together, we have identified a subset of irx genes whose expression patterns reveal subdivisions of the developing pronephric nephron. Most importantly, irx3 is expressed well before the segment-restricted expression of terminal differentiation markers.

Figure 2.

Expression of irx genes is highly regionalized in the developing pronephric kidney. (A–C) Expression patterns of irx1 (A), irx2 (B), and irx3 (C) in the pronephric kidneys of stage 35/36 Xenopus embryos as determined by whole-mount in situ hybridization. Lateral views of whole embryos (left panels; arrowheads indicate pronephric expression), enlargements of the pronephric region (middle panels), and color-coded schematic representations of the segment-restricted expression domains (right panels) are shown. Note the sharp boundaries that limit the expression domains of irx genes in the developing nephron. (D) Summary of the temporal expression profiles of irx genes during pronephric kidney development. The embryonic stages of X. laevis development are indicated. High and low levels of irx gene expression are illustrated with thick and thin lines, respectively. The embryonic expression patterns in early embryos are shown in Supplementary Figure 1.

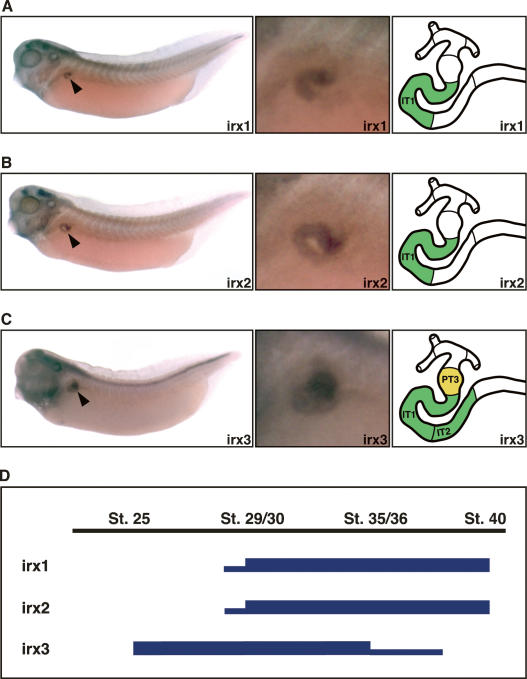

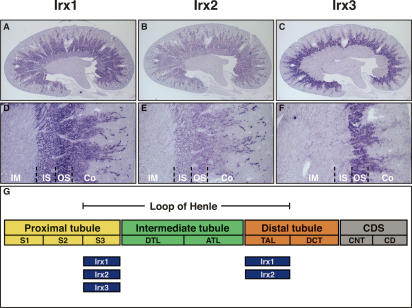

In the mouse, we examined expression of all six Irx genes in developing metanephric kidneys at embryonic day 18.5 (E18.5) and in adult kidneys. As in Xenopus, we detected renal expression of Irx1, Irx2, and Irx3 but not for Irx4, Irx5, and Irx6 (Figs. 3, 4; data not shown). During metanephric kidney development, signals from the ureteric bud initiate nephrogenesis by promoting condensation and epithelialization of the metanephric mesenchyme to form renal vesicles. Through a series of invaginations and elongations, renal vesicles are subsequently transformed first into comma-shaped and then into S-shaped bodies, which exhibit the first morphologic signs of nephron segmentation (Saxén 1987). Analysis of nephrogenesis in the E18.5 kidney revealed that Irx gene expression became first apparent in early comma-shaped bodies, where Irx3 transcripts were detected at low levels (Fig. 3G). In S-shaped bodies, transcripts of all three Irx genes were confined to intermediate domains of the developing nephron with high level of expression for Irx1, intermediate for Irx2, and low for Irx3 (Fig. 3E–G,I–K). In contrast, expression of Brn1 was broader covering both intermediate and distal domains of the S-shaped body at this stage (Fig. 3H,L), which is consistent with its role in the development of intermediate and distal nephron derivatives (Nakai et al. 2003).

Figure 3.

Irx gene expression marks an intermediate region of the S-shaped body. In situ hybridizations were performed on paraffin sections of E18.5 kidneys. Whole sagittal sections (A–D) and magnifications (E–H) of the renal cortex are shown to illustrate gene expression in developing nephrons. (I–L) The corresponding gene expression domains in the S-shaped body are indicated in the schematic drawings. (A–C) Irx1 and Irx2 are expressed in newly forming nephrons in the cortex (arrows) and the developing intermediate tubule epithelia (arrowheads). Irx3 expression is similar to Irx1 and Irx2, but fainter and more restricted. (D) Brn1 expression in the newly forming nephrons (arrowhead) and developing distal tubule epithelia (arrow). Note that in contrast to Irx genes, Brn1 is also highly expressed in epithelia of the renal papilla (asterisk). (I–K) Irx transcripts are confined to intermediate regions of S-shaped bodies. (L) Brn1 transcripts are detected in intermediate and distal domains of the S-shaped body. (CB) Comma-shaped body; (SB) S-shaped body; (P) proximal pole of the nephron; (D) distal pole of the nephron.

Figure 4.

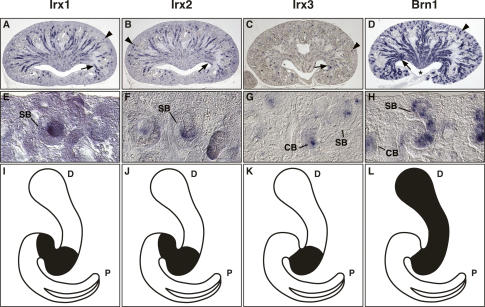

Irx gene expression is confined to distinct segments of Henle’s loop in the adult metanephric kidney. (A–F) Expression of Irx genes in the adult kidney. In situ hybridizations were performed on paraffin sections. Whole sagittal sections (A–C) and magnifications (D–F) are shown to illustrate Irx gene expression in detail. (Co) Cortex; (OS) outer stripe of outer medulla; (IS) inner stripe of the outer medulla; (IM) inner medulla. (A,B,D,E) Irx1 and Irx2 transcripts are detected in S3 and TAL. (C,F) Irx3 transcripts are confined to S3 only. (G) Summary of Irx gene expression in the adult metanephric kidney. The segmental organization of the adult metanephric nephron is shown schematically. The expression domains of each Irx gene are indicated below the scheme. (ATL) Ascending thin limb; (CD) collecting duct; (CDS) collecting duct system; (CNT) connecting tubule; (DCT) distal convoluted tubule; (DTL) descending thin limb; (S1, S2, S3) segments of the proximal tubule; (TAL) thick ascending limb.

Regionalized Irx gene expression persisted in adult kidneys with expression domains being confined to specific nephron segments of the loop of Henle (Fig. 4). The loop of Henle is comprised of the S3 proximal tubule, the descending thin limb (DTL), the ascending thin limb (ATL), and the thick ascending limb (TAL) (Kriz and Bankir 1988). Irx1 and Irx2 transcripts were both present in S3 proximal tubule segments and in the TALs, whereas Irx3 expression was confined solely to the S3 segment (Fig. 4). Expression was not detected in the thin limbs of Henle of the adult kidney. In summary, a subgroup of Irx genes—namely, Irx1, Irx2, and Irx3—is expressed in specific and overlapping patterns in the developing and adult mouse kidney. Most importantly, the developing nephron segments expressing Irx genes comprise the prospective loop of Henle (Fig. 3). Moreover, the comparison between Xenopus and mouse has revealed striking similarities with regard to the scope of Irx gene family member expression, developmental timing of Irx gene expression, and spatial expression domains during kidney development. This indicates that the mechanisms responsible for patterning the intermediate compartment of the vertebrate nephron have remained remarkably conserved during tetrapod evolution.

Irx3 gene function is required for patterning of the nephron

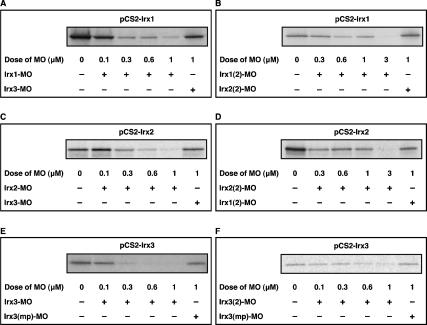

The expression studies in Xenopus and mouse suggest a function for Irx genes in patterning the nephron by specifying intermediate tubule and Henle’s loop fates, respectively. Given the potential redundancy of Irx gene activities, we opted for a loss-of-function approach in Xenopus embryos to test this hypothesis. Morpholino (MO) antisense oligonucleotides were used to block irx gene functions by inhibiting mRNA translation either one by one or in combinations. Two independent MOs were designed for each Xenopus irx gene under investigation. Special care was taken to ensure that the selected MOs inhibit transcripts from both pseudoallelic irx genes typically present in the pseudotetraploid Xenopus laevis genome. All Irx MOs (Irx-MO) were able to inhibit in a concentration-dependent manner translation in cell-free coupled transcription–translation assays (Fig. 5). Importantly, Irx3-MO was unable to block translation of irx1 and irx2. Different doses of Irx-MOs, typically 5 ng, were injected into single V2 blastomeres of eight-cell-stage embryos to target the prospective pronephric anlage (Saulnier et al. 2002b). The resulting embryos were analyzed by visual inspection for externally visible defects and by in situ hybridization for changes in pronephric marker gene expression.

Figure 5.

Inhibition of irx1, irx2, and irx3 translation in vitro by antisense MOs. Plasmids (500 ng) encoding the ORF of irx1, irx2, or irx3 were used as templates in cell-free coupled transcription–translation reactions. MOs were tested for inhibition of translation at the doses indicated. Cell-free transcription–translation reactions were performed in the presence of [35S]methionine and analyzed by SDS-PAGE/autoradiography. (A,B) Dose-response analysis of inhibition of irx1 translation by Irx1-MO (A) and Irx1(2)-MO (B). (C,D) Dose-response analysis of inhibition of irx2 translation by Irx2-MO (C) and Irx2(2)-MO (D). (E,F) Dose-response analysis of inhibition of irx3 translation by Irx3-MO (E) and Irx3(2)-MO (F).

In a first set of experiments, we tested the effect of blocking irx1, irx2, and irx3 gene functions simultaneously in the Xenopus embryo by unilateral injection of 5 ng of each Irx-MO into V2 blastomeres. The resulting embryos exhibited severe developmental defects, such as unilateral shortening of the body axes, which precluded the analysis of possible pronephric phenotypes (Supplementary Fig. 2). Thus, loss of irx1, irx2, and irx3 gene functions appears to be incompatible with normal embryonic development in Xenopus. Next, we performed knockdowns of irx1 and irx2 gene functions either alone (5 ng and 10 ng MO) or in combination (5 ng MO each). In each case, we failed to observe any externally visible defects. Furthermore, the expression of pronephric marker genes (pax2, clcnk, slc5a11, and slc12a1) was overall normal (Supplementary Fig. 3A; data not shown). Similar results were obtained using alternate MOs directed against irx1 and irx2 (Supplementary Fig. 3B; data not shown). Taken together, our findings strongly suggest that both irx1 and irx2 are dispensable for morphogenesis and patterning of the Xenopus pronephric kidney. Interestingly, Irx2 is neither required for kidney organogenesis in mice, since homozygous Irx2 mutants are phenotypically normal (Lebel et al. 2003).

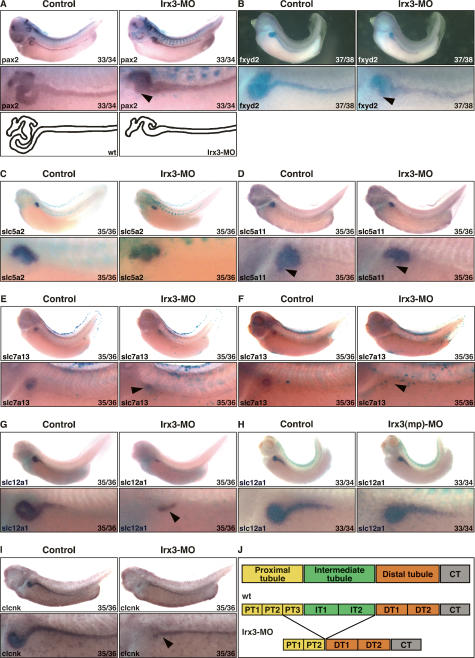

In contrast, injection of Irx3-MO led in the majority of the embryos to highly specific defects in pronephric kidney development, which are shown in Figure 5 and described in detail below. Irx3(2)-MO, a MO directed against the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) of irx3, caused similar pronephric phenotypes. With each Irx3-MO we observed in a smaller fraction, typically 25%, of the injected embryos malformations and absence of pronephric kidneys, indicating that irx3 may have an early essential function during Xenopus development, which will be explored elsewhere. Embryos injected with Irx3(mp)-MO, a control nonblocking Irx3-MO-containing mutation in four positions, were phenotypically normal (Figs. 5, 6H; data not shown). Irx3 knockdown embryos with normal overall appearance were selected and probed for evidence of defects in nephron organization. The transcription factor pax2 is an early marker of the pronephric anlage, and its expression is subsequently found in all developing pronephric epithelia (Heller and Brändli 1997). Staining of Irx3-MO-injected embryos for pax2 expression revealed the presence of pronephric kidneys, indicating that the specification of the pronephric fate had occurred during gastrulation. The pronephric kidneys were, however, frequently (72%, n = 25) characterized by abnormal morphology of the looped central domain, whereas the flanking proximal and distal domains appeared unaffected (Fig. 6A). As shown in Figure 6B, this phenotype was also observed in 65% (n = 43) of the Irx3-MO injected embryos stained for fxyd2 (Na, K-ATPase γ subunit), which is expressed throughout the nephron (Eid and Brändli 2001). These findings indicate that loss of irx3 gene function did not cause a general block in terminal differentiation of pronephric epithelia.

Figure 6.

Irx3 is required for intermediate tubule formation in the Xenopus pronephric kidney. (A–I) Irx3-MO (5 ng; A–G, I) or Irx3(mp)-MO (5 ng; H) and mRNA (0.25 ng) for the lineage tracer nuclear β-galactosidase were coinjected into single V2 blastomeres of eight-cell-stage embryos. Injected embryos were raised to the embryonic stage indicated, fixed, and processed for β-gal activity. Expression of marker genes was subsequently visualized by in situ hybridization. Control and injected sides are shown as lateral views with accompanying enlargements of the pronephric kidney region. (A,B) Irx3 knockdown affects pronephric morphogenesis. Arrowheads indicate the central looped region that is abnormal. Schematic representations show the outline of the nephron in normal and Irx3-MO-injected embryos. (C) Irx3 knockdown does not affect PT1 and PT2. (D–F) Irx3 knockdown causes a loss of the proximal tubule segment PT3. The arrowhead indicates the position of the PT3 segment. Examples of strong reduction (E) and complete loss (F) of slc7a13 expression are shown. (G–I) Irx3 knockdown causes loss of IT1 and IT2 but not of DT1. Arrowheads indicate the location of DT1. Note that slc12a1 expression remains unaffected in the presence of the control Irx3(mp)-MO (H). (J) Summary illustrating the nephron segmentation defects seen in irx3 knockdown embryos. See Figure 1C for the nomenclature of pronephric nephron segments and their abbreviations.

Next, we probed Irx3-MO-injected embryos for patterning defects along the proximodistal axis of the nephron using marker genes shown in Figure 1 and Table 1. Expression of slc5a2, a marker of PT1 and PT2, was retained, and there was no evidence indicating expansion of slc5a2 expression into more distal territories of the nephron (Fig. 6C). In the case of slc5a11 (Fig. 6D), the expression domains corresponding to PT1 and PT2 were again present, but expression in the distal PT3 domain was lost in the majority of the embryos (86%, n = 37). Analysis of irx3 knockdown embryos with the PT3 marker slc7a13 indicated that the loss of PT3 was less pronounced, but could still be detected in 36% (n = 55) of the injected embryos (Fig. 6E,F). Effects of irx3 knockdown on the formation of the intermediate tubule were analyzed by staining for slc12a1 and clcnk expression (Fig. 6G–I). The marker gene slc12a1 is expressed distal to slc5a11 and slc7a13 in the intermediate tubule and DT1. Interestingly, slc12a1 expression in the intermediate tubule segments IT1 and IT2 was no longer detectable, but residual staining remained associated with DT1 in the majority of Irx3-MO-injected embryos (72%, n = 138). Similarly, expression of clcnk was lost in IT1 and IT2 but retained in DT1 and the more distal nephron segments (82%, n = 33). In summary, our findings indicate that, consistent with its expression pattern (Fig. 2C), irx3 gene function is required for the formation of PT3 and intermediate tubules during nephron development (Fig. 6J).

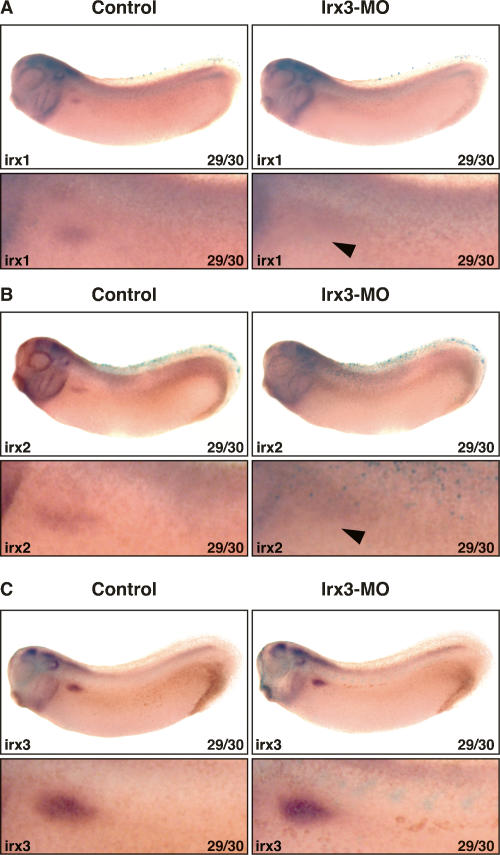

Next we asked whether the expression of pronephric irx genes is dependent on irx3 gene function. For this purpose, irx3 knockdown embryos were raised until they reached stage 29/30, when expression of all three irx genes could be detected (Fig. 2D; Supplementary Fig. 1). The analysis revealed that irx3 knockdown embryos failed to initiate expression of irx1 as well as of irx2 in 71% of the injected embryos (n = 14 for each gene), indicating that expression of these genes requires irx3 gene function (Fig. 7A,B). In contrast, regionalized pronephric irx3 transcripts were readily detected in the majority of the injected embryos (63%, n = 16) (Fig. 7C). Hence, the block of irx3 translation does not impair irx3 transcription, indicating that the irx3 gene is not subjected to autoregulation during early pronephric kidney development. Importantly, the regionalized pronephric expression pattern of irx3 is retained in the irx3 knockdown embryos. This suggests that nephron patterning is initiated normally but subsequent steps of intermediate tubule development are disrupted, resulting in the loss of the PT3, IT1, and IT2 segments. Notably, since the expression of irx1 and irx2 requires irx3 gene function, they are not able to compensate for the loss of irx3.

Figure 7.

Pronephric expression of irx1 and irx2 but not irx3 requires irx3 gene function. Irx3-MO (5 ng) and mRNA (0.25 ng) for the lineage tracer nuclear β-galactosidase were coinjected into single V2 blastomeres of eight-cell-stage embryos. Injected embryos were raised to the embryonic stage indicated, fixed, and processed for β-gal activity. Expression of marker genes was subsequently visualized by in situ hybridization. Control and injected sides are shown as lateral views with accompanying enlargements of the pronephric kidney region. (A,B) Irx3 knockdown disrupts irx1 and irx2 expression in the developing pronephric kidney. Arrowheads indicate the pronephric area devoid of irx1 (A) and irx2 (B) expression. (C) Irx3 knockdown does not affect irx3 expression.

Irx3 is sufficient to specify intermediate tubule fate

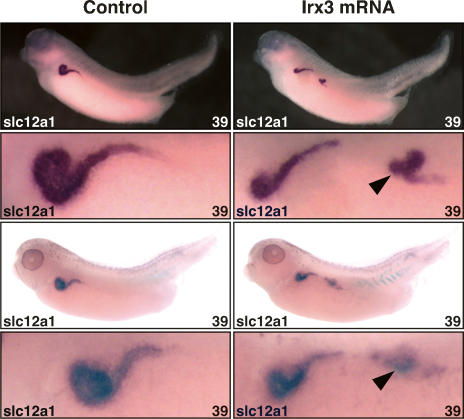

To assess whether irx3 might specify intermediate tubule fate, ectopic expression experiments were carried out. Injections of irx3 mRNA (0.15 ng or 0.25 ng) into one blastomere of two-cell-stage embryos or the V2 blastomere of eight-cell-stage embryos were performed. Embryos where then raised, fixed, and processed by in situ hybridization for expression of the intermediate tubule marker slc12a1. Of the injected embryos, 40%–60% failed to gastrulate normally resulting in severe developmental abnormalities, such as defects in neural tube closure. Irx3-injected embryos devoid of obvious developmental defects were subjected to marker gene analysis. Remarkably, irx3 misexpression resulted in the formation of ectopic slc12a1-expressing intermediate tubule tissues (Fig. 8). This phenotype occurred in 5%–14% of the embryos (n = 190) in three independent experiments. Interestingly, ectopic slc12a1-expressing tissues were always located in the intermediate mesoderm posterior to the pronephric kidney. This suggests that only the posterior intermediate mesoderm is competent to undergo cell fate change to form ectopic intermediate tubule tissue in response to irx3 misexpression. Taken together, these results demonstrate that ectopic expression of irx3 is sufficient to specify intermediate tubule fate.

Figure 8.

Irx3 is sufficient for intermediate tubule formation in the Xenopus pronephric kidney. Single V2 blastomeres of eight-cell-stage embryos were injected with irx3 mRNA (0.15 ng). Injected embryos were raised to the embryonic stage indicated, fixed, and processed for β-gal activity. Expression of the slc12a1 marker gene was subsequently visualized by in situ hybridization. Lateral views of control and injected sides of two representative embryos displaying the gain-of-function phenotype are shown with accompanying enlargements of the pronephric kidney region. The arrowheads indicate the ectopic intermediate tubule tissues expressing slc12a1.

Discussion

Within the nephron, the loop of Henle has a unique structure that enables the generation of hypertonic urine and the maintenance of water homeostasis. It is composed of four nephron segments (S3, DTL, ATL, and TAL) (Kriz and Bankir 1988) that arise from the intermediate region of the developing nephron. Four distinct stages of Henle’s loop development can be distinguished: the anlage, the primitive loop, the immature loop, and the mature loop (Neiss 1982; Nakai et al. 2003). To date, Brn1 is the only gene known to be essential for development of the loop of Henle, which is arrested at the primitive loop stage in Brn1 mutants (Nakai et al. 2003).

In the present study, we have identified Irx genes as critical factors for patterning the intermediate region of the developing vertebrate nephron. In the Xenopus and mouse, a conserved subset of Irx genes was expressed in overlapping domains, constituting an intermediate region of the developing nephron that will give rise to PT3 and the intermediate tubule in Xenopus and Henle’s loop in the mouse. Hence, Irx gene expression prefigures the future segmental organization of the nephron. Unlike many transcription factors regulating early development, Irx gene expression in the developing nephron is not transient but remains segmentally restricted into adulthood. In the mouse, expression persists in the thick limbs (S3 and TAL) but not in the thin limbs of Henle (DTL and ATL). Interestingly, direct evidence for a late function of Irx genes was recently provided by studies of Irx5-deficient mice, where Irx5 maintains asymmetric potassium channel expression (Costantini et al. 2005). Thus, Irx genes may serve as determining factors in the developing nephron and subsequently as maintenance factors ensuring persistent segment-specific gene expression in the mature nephron. Notably, expression of Hes5, a hairy-related basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH) transcription factor and target of Notch signaling, is also restricted to an intermediate segment of the S-shaped body (Piscione et al. 2004; Chen and Al-Awqati 2005). Hes5 mutant mice, however, fail to display any defects in nephrogenesis (Chen and Al-Awqati 2005).

The gain- and loss-of-function studies reported here directly address the functional significance of Irx genes in specifying nephron segment identity. The overlapping gene expression patterns of Irx genes suggest redundant roles in the developing nephron. This notion was confirmed as blocking of irx1 and irx2 translation either alone or together did not affect nephron patterning and differentiation in Xenopus. Redundant roles for Irx genes have also been reported in the mouse, where the loss of function of Irx genes does not significantly affect embryonic development (Bruneau et al. 2001; Lebel et al. 2003; Costantini et al. 2005). In contrast, knockdown of Xenopus irx3 function caused a profound patterning defect in the developing pronephric nephron manifesting in the deletion of segments spanning from PT3 to IT2. Interestingly, the affected region did not adopt the fate of adjacent nephron segments, as we failed to observe any marker gene expansion. This indicates that irx3 may not function to repress proximal and/or distal fates in the developing intermediate tubule segments. It is therefore also unlikely that there is a default program establishing initially either a proximal or distal fate in the prospective central region of the developing nephron, which will subsequently adopt intermediate tubule fate upon irx3 gene activation. Rather, our findings indicate that intermediate tubule fate is established together with proximal and distal tubule fates. We conclude that irx3 is required to specify PT3 and the entire intermediate tubule. Given that the pronephric nephron shares a segmental complexity that is remarkably comparable with that of the metanephric nephron, we infer that Irx genes may play an equally important role in nephron patterning and segmentation in mammals. More specifically, we propose that Irx genes are required to specify nephron segments that will give rise to the loop of Henle.

In Drosophila, the Iroquois complex (Iro-C) encodes a cluster of three related homeodomain genes—named araucan, caupolican, and mirror—that are homologs of the vertebrate Irx genes (Cavodeassi et al. 2001). Overexpression of Iro-C genes imposes notum differentiation fate on cells of the imaginal wing disc (Wang et al. 2000; Aldaz et al. 2003). Interestingly, the gain-of-function experiments reported here demonstrate unequivocally that Xenopus irx3 acts as a master regulator of intermediate tubule development that is sufficient to specify intermediate tubule fate in vivo. It therefore appears that the ability of irx-related genes to specify cell fate has been conserved between Drosophila and vertebrates. Remarkably, the ectopic intermediate tubules induced by irx3 undergo terminal differentiation and were detected at frequencies of 5%–14%, which are comparable with the induction of ectopic eyes in 5.8% of the Xenopus embryos injected with the master regulator pax6 (Chow et al. 1999). The irx3 gain-of-function phenotype appears at first sight surprising, since Irx genes are thought to act mainly as transcriptional repressors (Bilioni et al. 2005). However, IRX4 was shown previously to act as a transcriptional activator required for heart development in chicken (Bao et al. 1999). Moreover, FGF signaling can stimulate phosphorylation of Irx proteins that will convert them from transcriptional repressors to activators (Matsumoto et al. 2004). Thus, the transcriptional activity of Irx proteins is regulated in a context-dependent manner. Ectopic intermediate tubules are only detected in the intermediate mesoderm and not elsewhere in the developing embryo. Moreover, only the posterior intermediate mesoderm is competent to respond to ectopic irx3 expression. Interestingly, this portion of the intermediate mesoderm has nephrogenic potential, as it will later give rise to the mesonephric kidney. Whether the ectopic intermediate tubules are of pronephric or mesonephric origin cannot presently be determined due to the lack of specific markers.

The loop of Henle is a structure exclusively found in birds and mammals, which are the only vertebrate groups that retain body water by producing urine osmotically more concentrated than the plasma from which it is derived (Casotti et al. 2000). The kidneys of larval and adult amphibians do not develop loops of Henle. Their urine concentration is hypoosmotic to plasma, and they produce very dilute urine in freshwater (Vize et al. 2003). Despite the inability to generate loops of Henle, our analysis of irx gene expression and function in Xenopus embryos clearly demonstrates the existence of a patterning mechanism to specify an intermediate compartment in the pronephric nephron. The physiological roles of the intermediate tubule in the Xenopus pronephros are currently not known, but are likely to involve the reabsorption of salt ions as evidenced by the prominent expression of slc12a1 (Na-K-Cl symporter). The molecular mechanism for specifying intermediate tubule fate therefore predates the establishment of Henle’s loop in higher vertebrates. Moreover, it indicates that the ability to generate an intermediate tubule compartment is evolutionary ancient, and may have been established at the onset of tetrapod evolution.

Besides Irx genes, Brn1, a POU transcription factor, represents the other early patterning gene required for the specification of the intermediate nephron and essential for the function of Henle’s loop (Nakai et al. 2003). Polarized Brn1 expression is evident already at the renal vesicle stage and covers a broad intermediate and distal domain of the developing nephron, while Irx gene expression is detectable in early comma-shaped bodies and confined solely to the intermediate region in S-shaped bodies. Whether Brn1 and Irx genes act in concert in the same pathway or represent separate parallel pathways that insure intermediate tubule development is currently not known. Preliminary studies indicate that the Xenopus embryo expresses several class III POU transcription factors including brn1 during pronephric kidney organogenesis (L. Reggiani and A.W. Brändli, unpubl.). The Xenopus pronephros may therefore be a useful model to study the epistatic relationship of these genes.

The kidney is a common target of systemic diseases, developmental syndromes, and drug toxicity. As a consequence, selective damage or loss of epithelial cell types may incur and impair normal renal functions. Given its instructive properties, Irx3 may be exploited to drive differentiation of renal progenitors derived from embryonic stem cells (Kim and Dressler 2005) toward intermediate tubule fate. Hence, the present work provides not only a novel framework for understanding how transcription factors direct formation of nephron segments but also suggests new approaches for renal tissue engineering and possible treatment of renal diseases by cell replacement therapy.

Materials and methods

Gene nomenclature

The standard gene nomenclature suggested by Xenbase (http://www.xenbase.org) and adopted by the NCBI for Xenopus genes is utilized rather than the original gene names to maximize compatibility with data available from other model systems. Where possible, Xenopus gene names are the same as the human orthologs.

Cloning of cDNAs, sequencing, and sequence analysis

Expressed sequence tag (EST) databases were screened to identify the cDNAs encoding slc transporters from X. laevis (D. Raciti, unpubl.). Among them, slc5a2 (GenBank accession no. CF520680), slc7a13 (BC060020), slc12a1 (BU904428), and slc12a3 (CA790325) were employed in this study as pronephric marker genes. Double-stranded DNA sequencing was performed in-house. Assembly of nucleotide sequence traces and analysis of nucleotides and protein sequences was performed using the DNAStar Lasergene software package (version 6.0).

Plasmid constructs

The following plasmids containing the complete ORF of Xenopus irx1 (Gomez-Skarmeta et al. 1998), irx2 (Gomez-Skarmeta et al. 1998), and irx3 (Bellefroid et al. 1998) were constructed for in vitro coupled transcription–translation reaction and in vitro RNA synthesis: pCS2-Irx1, pCS2-Irx2, and pCS2-Irx3. The cDNAs were amplified by PCR (Expand High-Fidelity PCR System, Roche Diagnostics) and subcloned into the pCS2+ vector (Turner and Weintraub 1994) using T4 DNA Ligase (Fermentas). All constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Xenopus embryo manipulation and in situ hybridization

In vitro fertilization, culture, and staging of Xenopus embryos were performed as previously described (Brändli and Kirschner 1995; Helbling et al. 1998). Probe synthesis, whole-mount in situ hybridization, β-galactosidase staining, and bleaching of embryos were carried out as described (Helbling et al. 1998, 1999; Saulnier et al. 2002b). Digoxigenin probes were generated from linearized plasmids encoding irx1 (Xiro) and irx2 (Xiro2) (Gomez-Skarmeta et al. 1998), irx3 (Xiro3) (Bellefroid et al. 1998), irx4 and irx5 (Garriock et al. 2001), pax2 (Heller and Brändli 1997), clcnk (ClC-K) (Maulet et al. 1999), fxyd2 (Na, K-ATPase γ-subunit) (Eid and Brändli 2001), slc5a11 (SGLT1-L) (Eid et al. 2002), slc7a13 (GenBank accession no. BC060020), slc12a1 (BU904428), slc12a3 (CA790325), slc5a2 (CF520680), and wnt4 (Saulnier et al. 2002a). Sense strand controls were prepared from all plasmids and then tested negative by in situ hybridization.

Contour model of the pronephric nephron and marker gene mapping

The pronephric expression patterns of 91 slc genes, along with a full account of how the segmental organization of the Xenopus pronephric kidney was determined and how the accompanying nomenclature was established, will be presented elsewhere (D. Raciti, L. Raggiani, and A.W. Brändli, in prep.). In brief, a first schematic representation of the contour of the stage 35/36 nephron was developed from Xenopus embryos stained by whole-mount in situ hybridization with a combination of probes for the pronephric marker genes fxyd2 (Eid and Brändli 2001), pax2 (Heller and Brändli 1997), and wnt4 (Saulnier et al. 2002a). Two dozen stained embryos were inspected to generate a two-dimensional contour drawing of the nephron on paper. Refinements to the initial contour model were made after inspection of hundreds of embryos stained with other pronephric marker genes. The final contour model of the nephron shown in Figure 1C was made with Illustrator CS2 (Adobe).

The pronephric expression patterns of 91 slc genes were projected onto the contour model to define the segments of the nephron. Unambiguous morphological features, such as the nephrostomes, a characteristically broad proximal tubule domain known as common tubule (Fox 1963) (subsequently named PT3), and the looped part of the pronephric nephron (IT1, IT2, and DT1), were used as landmarks to identify the relative location of the boundaries of the expression domains. The final borders between the nephron segments are defined by the boundaries of multiple marker genes.

Microinjection of Xenopus embryos

The following antisense MO oligonucleotides were ordered from GeneTools to inhibit translation of Xenopus mRNAs (sequence complementary to the predicted start codon is underlined; mispaired nucleotides are indicated with small letters): Irx1-MO, 5′-CATGTCTCTCCGGCAGGGAAATCGC-3′; Irx1(2)MO, 5′-CCCAGCTGCGGGAAGGACATGTCTC-3′; Irx2-MO, 5′-GGTAACCCTGAGGATAGGACATGGT-3′; Irx2(2)-MO, 5′-G CAGAAGCACAGAATCGCCGGGGCT-3′; Irx3-MO, 5′-AGCT GTGGGAAGGACATGGTGCAGC-3′; Irx3(mp)-MO, 5′-AGgTGT GGGtAGGACAgGGTGaAGC-3′; Irx3(2)-MO, 5′-GAATCCCCTT TTATGACCTGACTTT-3′.

In vitro coupled transcription translation assays were carried out as described previously (Saulnier et al. 2002b). When not indicated differently, 5 ng of individual MOs were injected in V2 blastomere of eight-cell-stage embryos (Moody and Kline 1990). RNA synthesis and microinjection were performed as described (Helbling et al. 1998) except that RNA purification was done by phenol-chloroform extraction. RNA encoding the lineage tracer nuclear β-galactosidase (nucβgal) was usually coinjected at 0.25 ng per blastomere.

In situ hybridization of mouse kidneys and kidney sections

Mouse embryos were obtained from matings of NMRI wild-type animals. For timed pregnancies, plugs were checked in the morning after mating, noon was taken as 0.5 d post-coitum (dpc). Microdissected metanephric kidneys were fixed in 4% PFA and stored in 100% methanol at −20°C prior to in situ hybridization analysis. In situ hybridization analysis of 10-μm paraffin sections of embryonic kidneys at E18.5 and 6-wk-old adult kidneys was performed according to an established protocol (Soufan et al. 2004). Digoxigenin-labeled probes were transcribed from linearized plasmids encoding the following mouse cDNAs: Irx1 (GenBank accession no. BU703212), Irx2 (BI111057), Irx3 (BI525434), Irx4 (BE367799), Irx5 (Bosse et al. 2000), and Irx6 (Peters et al. 2000). For probe synthesis, the mouse Brn1 cDNA (Hara et al. 1992) was subcloned by PCR into pGEM-TEasy (Promega).

Photography and computer graphics

Mouse kidney sections were embedded in moviol and photographed on Leica Axioplan with a ProgResC14 digital camera. All images of mouse specimens were processed in Adobe Photoshop 8.0. Digital photographs of whole-mount Xenopus embryos were taken with an AxioCam Color camera mounted on a Zeiss SteREO Lumar.V12 stereomicroscope. Composite figures were assembled and labeled with Adobe Photoshop CS2 and Adobe InDesign CS2. Schematic figures were drawn using Adobe Illustrator CS2.

Acknowledgments

We thank E. Bellefroid, J.L. Gómez-Skarmeta, P. Krieg, Y. Maulet, M. Nirenberg, and U. Rüther for providing plasmids; M. Petry for excellent technical assistance with mouse in situ hybridization analysis; F. Rechfeld for subcloning of Brn1; B. Kaissling for annotation of mouse Irx gene expression patterns; and M. Reggiani for assistance with computer graphics. This work was supported by grants from the German Research Council (DFG) to A.K. and the Swiss National Science Foundation (3100A0-101964) and European Community (EuReGene LSHG-CT-2004-005085) to A.W.B.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available at http://www.genesdev.org.

Article is online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.450707

References

- Aldaz S., Morata G., Azpiazu N., Morata G., Azpiazu N., Azpiazu N. The Pax-homeobox gene eyegone is involved in the subdivision of the thorax of Drosophila. Development. 2003;130:4473–4482. doi: 10.1242/dev.00643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allanson J.E., Hunter A.G., Mettler G.S., Jimenez C., Hunter A.G., Mettler G.S., Jimenez C., Mettler G.S., Jimenez C., Jimenez C. Renal tubular dysgenesis: A not uncommon autosomal recessive syndrome: A review. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1992;43:811–814. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320430512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao Z.Z., Bruneau B.G., Seidman J.G., Seidman C.E., Cepko C.L., Bruneau B.G., Seidman J.G., Seidman C.E., Cepko C.L., Seidman J.G., Seidman C.E., Cepko C.L., Seidman C.E., Cepko C.L., Cepko C.L. Regulation of chamber-specific gene expression in the developing heart by Irx4. Science. 1999;283:1161–1164. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5405.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellefroid E.J., Kobbe A., Gruss P., Pieler T., Gurdon J.B., Papalopulu N., Kobbe A., Gruss P., Pieler T., Gurdon J.B., Papalopulu N., Gruss P., Pieler T., Gurdon J.B., Papalopulu N., Pieler T., Gurdon J.B., Papalopulu N., Gurdon J.B., Papalopulu N., Papalopulu N. Xiro3 encodes a Xenopus homolog of the Drosophila Iroquois genes and functions in neural specification. EMBO J. 1998;17:191–203. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.1.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilioni A., Craig G., Hill C., McNeill H., Craig G., Hill C., McNeill H., Hill C., McNeill H., McNeill H. Iroquois transcription factors recognize a unique motif to mediate transcriptional repression in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2005;102:14671–14676. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502480102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosse A., Stoykova A., Nieselt-Struwe K., Chowdhury K., Copeland N.G., Jenkins N.A., Gruss P., Stoykova A., Nieselt-Struwe K., Chowdhury K., Copeland N.G., Jenkins N.A., Gruss P., Nieselt-Struwe K., Chowdhury K., Copeland N.G., Jenkins N.A., Gruss P., Chowdhury K., Copeland N.G., Jenkins N.A., Gruss P., Copeland N.G., Jenkins N.A., Gruss P., Jenkins N.A., Gruss P., Gruss P. Identification of a novel mouse Iroquois homeobox gene, Irx5, and chromosomal localisation of all members of the mouse Iroquois gene family. Dev. Dyn. 2000;218:160–174. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(200005)218:1<160::AID-DVDY14>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brändli A.W. Towards a molecular anatomy of the Xenopus pronephric kidney. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 1999;43:381–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brändli A.W., Kirschner M.W., Kirschner M.W. Molecular cloning of tyrosine kinases in the early Xenopus embryo: Identification of Eck-related genes expressed in cranial neural crest cells of the second (hyoid) arch. Dev. Dyn. 1995;203:119–140. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002030202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruneau B.G., Bao Z.Z., Fatkin D., Xavier-Neto J., Georgakopoulos D., Maguire C.T., Berul C.I., Kass D.A., Kuroski-de Bold M.L., de Bold A.J., Bao Z.Z., Fatkin D., Xavier-Neto J., Georgakopoulos D., Maguire C.T., Berul C.I., Kass D.A., Kuroski-de Bold M.L., de Bold A.J., Fatkin D., Xavier-Neto J., Georgakopoulos D., Maguire C.T., Berul C.I., Kass D.A., Kuroski-de Bold M.L., de Bold A.J., Xavier-Neto J., Georgakopoulos D., Maguire C.T., Berul C.I., Kass D.A., Kuroski-de Bold M.L., de Bold A.J., Georgakopoulos D., Maguire C.T., Berul C.I., Kass D.A., Kuroski-de Bold M.L., de Bold A.J., Maguire C.T., Berul C.I., Kass D.A., Kuroski-de Bold M.L., de Bold A.J., Berul C.I., Kass D.A., Kuroski-de Bold M.L., de Bold A.J., Kass D.A., Kuroski-de Bold M.L., de Bold A.J., Kuroski-de Bold M.L., de Bold A.J., de Bold A.J., et al. Cardiomyopathy in Irx4-deficient mice is preceded by abnormal ventricular gene expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:1730–1736. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.5.1730-1736.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casotti G., Lindberg K.K., Braun E.J., Lindberg K.K., Braun E.J., Braun E.J. Functional morphology of the avian medullary cone. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2000;279:R1722–R1730. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.5.R1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavodeassi F., Modolell J., Gomez-Skarmeta J.L., Modolell J., Gomez-Skarmeta J.L., Gomez-Skarmeta J.L. The Iroquois family of genes: From body building to neural patterning. Development. 2001;128:2847–2855. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.15.2847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Al-Awqati Q., Al-Awqati Q. Segmental expression of Notch and Hairy genes in nephrogenesis. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2005;288:F939–F952. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00369.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H.T., Miner J.H., Lin M., Tansey M.G., Roth K., Kopan R., Miner J.H., Lin M., Tansey M.G., Roth K., Kopan R., Lin M., Tansey M.G., Roth K., Kopan R., Tansey M.G., Roth K., Kopan R., Roth K., Kopan R., Kopan R. γ-Secretase activity is dispensable for mesenchyme-to-epithelium transition but required for podocyte and proximal tubule formation in developing mouse kidney. Development. 2003;130:5031–5042. doi: 10.1242/dev.00697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H.T., Kim M., Valerius M.T., Surendran K., Schuster-Gossler K., Gossler A., McMahon A.P., Kopan R., Kim M., Valerius M.T., Surendran K., Schuster-Gossler K., Gossler A., McMahon A.P., Kopan R., Valerius M.T., Surendran K., Schuster-Gossler K., Gossler A., McMahon A.P., Kopan R., Surendran K., Schuster-Gossler K., Gossler A., McMahon A.P., Kopan R., Schuster-Gossler K., Gossler A., McMahon A.P., Kopan R., Gossler A., McMahon A.P., Kopan R., McMahon A.P., Kopan R., Kopan R. Notch2, but not Notch1, is required for proximal fate acquisition in the mammalian nephron. Development. 2007;134:801–811. doi: 10.1242/dev.02773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow R.L., Altmann C.R., Lang R.A., Hemmati-Brivanlou A., Altmann C.R., Lang R.A., Hemmati-Brivanlou A., Lang R.A., Hemmati-Brivanlou A., Hemmati-Brivanlou A. Pax6 induces ectopic eyes in a vertebrate. Development. 1999;126:4213–4222. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.19.4213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costantini D.L., Arruda E.P., Agarwal P., Kim K.H., Zhu Y., Zhu W., Lebel M., Cheng C.W., Park C.Y., Pierce S.A., Arruda E.P., Agarwal P., Kim K.H., Zhu Y., Zhu W., Lebel M., Cheng C.W., Park C.Y., Pierce S.A., Agarwal P., Kim K.H., Zhu Y., Zhu W., Lebel M., Cheng C.W., Park C.Y., Pierce S.A., Kim K.H., Zhu Y., Zhu W., Lebel M., Cheng C.W., Park C.Y., Pierce S.A., Zhu Y., Zhu W., Lebel M., Cheng C.W., Park C.Y., Pierce S.A., Zhu W., Lebel M., Cheng C.W., Park C.Y., Pierce S.A., Lebel M., Cheng C.W., Park C.Y., Pierce S.A., Cheng C.W., Park C.Y., Pierce S.A., Park C.Y., Pierce S.A., Pierce S.A., et al. The homeodomain transcription factor Irx5 establishes the mouse cardiac ventricular repolarization gradient. Cell. 2005;123:347–358. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Calle-Mustienes E., Feijoo C.G., Manzanares M., Tena J.J., Rodriguez-Seguel E., Letizia A., Allende M.L., Gomez-Skarmeta J.L., Feijoo C.G., Manzanares M., Tena J.J., Rodriguez-Seguel E., Letizia A., Allende M.L., Gomez-Skarmeta J.L., Manzanares M., Tena J.J., Rodriguez-Seguel E., Letizia A., Allende M.L., Gomez-Skarmeta J.L., Tena J.J., Rodriguez-Seguel E., Letizia A., Allende M.L., Gomez-Skarmeta J.L., Rodriguez-Seguel E., Letizia A., Allende M.L., Gomez-Skarmeta J.L., Letizia A., Allende M.L., Gomez-Skarmeta J.L., Allende M.L., Gomez-Skarmeta J.L., Gomez-Skarmeta J.L. A functional survey of the enhancer activity of conserved non-coding sequences from vertebrate Iroquois cluster gene deserts. Genome Res. 2005;15:1061–1072. doi: 10.1101/gr.4004805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dressler G.R. The cellular basis of kidney development. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2006;22:509–529. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010305.104340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eid S.R., Brändli A.W., Brändli A.W. Xenopus Na,K-ATPase: Primary sequence of the β2 subunit and in situ localization of α1, β1, and γ expression during pronephric kidney development. Differentiation. 2001;68:115–125. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2001.680205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eid S.R., Terrettaz A., Nagata K., Brändli A.W., Terrettaz A., Nagata K., Brändli A.W., Nagata K., Brändli A.W., Brändli A.W. Embryonic expression of Xenopus SGLT-1L, a novel member of the solute carrier family 5 (SLC5), is confined to tubules of the pronephric kidney. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2002;46:177–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox H. The amphibian pronephros. Q. Rev. Biol. 1963;38:1–25. doi: 10.1086/403747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garriock R.J., Vokes S.A., Small E.M., Larson R., Krieg P.A., Vokes S.A., Small E.M., Larson R., Krieg P.A., Small E.M., Larson R., Krieg P.A., Larson R., Krieg P.A., Krieg P.A. Developmental expression of the Xenopus Iroquois-family homeobox genes, Irx4 and Irx5. Dev. Genes Evol. 2001;211:257–260. doi: 10.1007/s004270100147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Skarmeta J.L., Modolell J., Modolell J. Iroquois genes: Genomic organization and function in vertebrate neural development. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2002;12:403–408. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(02)00317-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Skarmeta J.L., Glavic A., de la Calle-Mustienes E., Modolell J., Mayor R., Glavic A., de la Calle-Mustienes E., Modolell J., Mayor R., de la Calle-Mustienes E., Modolell J., Mayor R., Modolell J., Mayor R., Mayor R. Xiro, a Xenopus homolog of the Drosophila Iroquois complex genes, controls development at the neural plate. EMBO J. 1998;17:181–190. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.1.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieshammer U., Cebrian C., Ilagan R., Meyers E., Herzlinger D., Martin G.R., Cebrian C., Ilagan R., Meyers E., Herzlinger D., Martin G.R., Ilagan R., Meyers E., Herzlinger D., Martin G.R., Meyers E., Herzlinger D., Martin G.R., Herzlinger D., Martin G.R., Martin G.R. FGF8 is required for cell survival at distinct stages of nephrogenesis and for regulation of gene expression in nascent nephrons. Development. 2005;132:3847–3857. doi: 10.1242/dev.01944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara Y., Rovescalli A.C., Kim Y., Nirenberg M., Rovescalli A.C., Kim Y., Nirenberg M., Kim Y., Nirenberg M., Nirenberg M. Structure and evolution of four POU domain genes expressed in mouse brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1992;89:3280–3284. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.8.3280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helbling P.M., Tran C.T., Brändli A.W., Tran C.T., Brändli A.W., Brändli A.W. Requirement for EphA receptor signaling in the segregation of Xenopus third and fourth arch neural crest cells. Mech. Dev. 1998;78:63–79. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00148-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helbling P.M., Saulnier D.M., Robinson V., Christiansen J.H., Wilkinson D.G., Brändli A.W., Saulnier D.M., Robinson V., Christiansen J.H., Wilkinson D.G., Brändli A.W., Robinson V., Christiansen J.H., Wilkinson D.G., Brändli A.W., Christiansen J.H., Wilkinson D.G., Brändli A.W., Wilkinson D.G., Brändli A.W., Brändli A.W. Comparative analysis of embryonic gene expression defines potential interaction sites for Xenopus EphB4 receptors with ephrin-B ligands. Dev. Dyn. 1999;216:361–373. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199912)216:4/5<361::AID-DVDY5>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller N., Brändli A.W., Brändli A.W. Xenopus Pax-2 displays multiple splice forms during embryogenesis and pronephric kidney development. Mech. Dev. 1997;69:83–104. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(97)00158-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houweling A.C., Dildrop R., Peters T., Mummenhoff J., Moorman A.F., Ruther U., Christoffels V.M., Dildrop R., Peters T., Mummenhoff J., Moorman A.F., Ruther U., Christoffels V.M., Peters T., Mummenhoff J., Moorman A.F., Ruther U., Christoffels V.M., Mummenhoff J., Moorman A.F., Ruther U., Christoffels V.M., Moorman A.F., Ruther U., Christoffels V.M., Ruther U., Christoffels V.M., Christoffels V.M. Gene and cluster-specific expression of the Iroquois family members during mouse development. Mech. Dev. 2001;107:169–174. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00451-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D., Dressler G.R., Dressler G.R. Nephrogenic factors promote differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells into renal epithelia. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2005;16:3527–3534. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005050544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K., Uchida S., Mizutani S., Sasaki S., Marumo F., Uchida S., Mizutani S., Sasaki S., Marumo F., Mizutani S., Sasaki S., Marumo F., Sasaki S., Marumo F., Marumo F. Intrarenal and cellular localization of CLC-K2 protein in the mouse kidney. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2001;12:1327–1334. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1271327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi A., Kwan K.M., Carroll T.J., McMahon A.P., Mendelsohn C.L., Behringer R.R., Kwan K.M., Carroll T.J., McMahon A.P., Mendelsohn C.L., Behringer R.R., Carroll T.J., McMahon A.P., Mendelsohn C.L., Behringer R.R., McMahon A.P., Mendelsohn C.L., Behringer R.R., Mendelsohn C.L., Behringer R.R., Behringer R.R. Distinct and sequential tissue-specific activities of the LIM-class homeobox gene Lim1 for tubular morphogenesis during kidney development. Development. 2005;132:2809–2823. doi: 10.1242/dev.01858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriz W., Bankir L., Bankir L. A standard nomenclature for structures of the kidney. The Renal Commission of the International Union of Physiological Sciences (IUPS) Kidney Int. 1988;33:1–7. doi: 10.1038/ki.1988.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebel M., Agarwal P., Cheng C.W., Kabir M.G., Chan T.Y., Thanabalasingham V., Zhang X., Cohen D.R., Husain M., Cheng S.H., Agarwal P., Cheng C.W., Kabir M.G., Chan T.Y., Thanabalasingham V., Zhang X., Cohen D.R., Husain M., Cheng S.H., Cheng C.W., Kabir M.G., Chan T.Y., Thanabalasingham V., Zhang X., Cohen D.R., Husain M., Cheng S.H., Kabir M.G., Chan T.Y., Thanabalasingham V., Zhang X., Cohen D.R., Husain M., Cheng S.H., Chan T.Y., Thanabalasingham V., Zhang X., Cohen D.R., Husain M., Cheng S.H., Thanabalasingham V., Zhang X., Cohen D.R., Husain M., Cheng S.H., Zhang X., Cohen D.R., Husain M., Cheng S.H., Cohen D.R., Husain M., Cheng S.H., Husain M., Cheng S.H., Cheng S.H., et al. The Iroquois homeobox gene Irx2 is not essential for normal development of the heart and midbrain–hindbrain boundary in mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:8216–8225. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.22.8216-8225.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loffing J., Loffing-Cueni D., Valderrabano V., Klausli L., Hebert S.C., Rossier B.C., Hoenderop J.G., Bindels R.J., Kaissling B., Loffing-Cueni D., Valderrabano V., Klausli L., Hebert S.C., Rossier B.C., Hoenderop J.G., Bindels R.J., Kaissling B., Valderrabano V., Klausli L., Hebert S.C., Rossier B.C., Hoenderop J.G., Bindels R.J., Kaissling B., Klausli L., Hebert S.C., Rossier B.C., Hoenderop J.G., Bindels R.J., Kaissling B., Hebert S.C., Rossier B.C., Hoenderop J.G., Bindels R.J., Kaissling B., Rossier B.C., Hoenderop J.G., Bindels R.J., Kaissling B., Hoenderop J.G., Bindels R.J., Kaissling B., Bindels R.J., Kaissling B., Kaissling B. Distribution of transcellular calcium and sodium transport pathways along mouse distal nephron. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2001;281:F1021–F1027. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.0085.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto K., Nishihara S., Kamimura M., Shiraishi T., Otoguro T., Uehara M., Maeda Y., Ogura K., Lumsden A., Ogura T., Nishihara S., Kamimura M., Shiraishi T., Otoguro T., Uehara M., Maeda Y., Ogura K., Lumsden A., Ogura T., Kamimura M., Shiraishi T., Otoguro T., Uehara M., Maeda Y., Ogura K., Lumsden A., Ogura T., Shiraishi T., Otoguro T., Uehara M., Maeda Y., Ogura K., Lumsden A., Ogura T., Otoguro T., Uehara M., Maeda Y., Ogura K., Lumsden A., Ogura T., Uehara M., Maeda Y., Ogura K., Lumsden A., Ogura T., Maeda Y., Ogura K., Lumsden A., Ogura T., Ogura K., Lumsden A., Ogura T., Lumsden A., Ogura T., Ogura T. The prepattern transcription factor Irx2, a target of the FGF8/MAP kinase cascade, is involved in cerebellum formation. Nat. Neurosci. 2004;7:605–612. doi: 10.1038/nn1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo H., Kanai Y., Kim J.Y., Chairoungdua A., Kim D.K., Inatomi J., Shigeta Y., Ishimine H., Chaekuntode S., Tachampa K., Kanai Y., Kim J.Y., Chairoungdua A., Kim D.K., Inatomi J., Shigeta Y., Ishimine H., Chaekuntode S., Tachampa K., Kim J.Y., Chairoungdua A., Kim D.K., Inatomi J., Shigeta Y., Ishimine H., Chaekuntode S., Tachampa K., Chairoungdua A., Kim D.K., Inatomi J., Shigeta Y., Ishimine H., Chaekuntode S., Tachampa K., Kim D.K., Inatomi J., Shigeta Y., Ishimine H., Chaekuntode S., Tachampa K., Inatomi J., Shigeta Y., Ishimine H., Chaekuntode S., Tachampa K., Shigeta Y., Ishimine H., Chaekuntode S., Tachampa K., Ishimine H., Chaekuntode S., Tachampa K., Chaekuntode S., Tachampa K., Tachampa K., et al. Identification of a novel Na+-independent acidic amino acid transporter with structural similarity to the member of a heterodimeric amino acid transporter family associated with unknown heavy chains. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:21017–21026. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200019200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maulet Y., Lambert R.C., Mykita S., Mouton J., Partisani M., Bailly Y., Bombarde G., Feltz A., Lambert R.C., Mykita S., Mouton J., Partisani M., Bailly Y., Bombarde G., Feltz A., Mykita S., Mouton J., Partisani M., Bailly Y., Bombarde G., Feltz A., Mouton J., Partisani M., Bailly Y., Bombarde G., Feltz A., Partisani M., Bailly Y., Bombarde G., Feltz A., Bailly Y., Bombarde G., Feltz A., Bombarde G., Feltz A., Feltz A. Expression and targeting to the plasma membrane of xClC-K, a chloride channel specifically expressed in distinct tubule segments of Xenopus laevis kidney. Biochem. J. 1999;340:737–743. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin K.A., Rones M.S., Mercola M., Rones M.S., Mercola M., Mercola M. Notch regulates cell fate in the developing pronephros. Dev. Biol. 2000;227:567–580. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mobjerg N., Larsen E.H., Jespersen A., Larsen E.H., Jespersen A., Jespersen A. Morphology of the kidney in larvae of Bufo viridis (Amphibia, Anura, Bufonidae) J. Morphol. 2000;245:177–195. doi: 10.1002/1097-4687(200009)245:3<177::AID-JMOR1>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody S.A., Kline M.J., Kline M.J. Segregation of fate during cleavage of frog (Xenopus laevis) blastomeres. Anat. Embryol. (Berl.) 1990;182:347–362. doi: 10.1007/BF02433495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mount D.B., Baekgaard A., Hall A.E., Plata C., Xu J., Beier D.R., Gamba G., Hebert S.C., Baekgaard A., Hall A.E., Plata C., Xu J., Beier D.R., Gamba G., Hebert S.C., Hall A.E., Plata C., Xu J., Beier D.R., Gamba G., Hebert S.C., Plata C., Xu J., Beier D.R., Gamba G., Hebert S.C., Xu J., Beier D.R., Gamba G., Hebert S.C., Beier D.R., Gamba G., Hebert S.C., Gamba G., Hebert S.C., Hebert S.C. Isoforms of the Na-K-2Cl cotransporter in murine TAL I. Molecular characterization and intrarenal localization. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;276:F347–F358. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.276.3.F347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakai S., Sugitani Y., Sato H., Ito S., Miura Y., Ogawa M., Nishi M., Jishage K., Minowa O., Noda T., Sugitani Y., Sato H., Ito S., Miura Y., Ogawa M., Nishi M., Jishage K., Minowa O., Noda T., Sato H., Ito S., Miura Y., Ogawa M., Nishi M., Jishage K., Minowa O., Noda T., Ito S., Miura Y., Ogawa M., Nishi M., Jishage K., Minowa O., Noda T., Miura Y., Ogawa M., Nishi M., Jishage K., Minowa O., Noda T., Ogawa M., Nishi M., Jishage K., Minowa O., Noda T., Nishi M., Jishage K., Minowa O., Noda T., Jishage K., Minowa O., Noda T., Minowa O., Noda T., Noda T. Crucial roles of Brn1 in distal tubule formation and function in mouse kidney. Development. 2003;130:4751–4759. doi: 10.1242/dev.00666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neiss W.F. Histogenesis of the loop of Henle in the rat kidney. Anat. Embryol. (Berl.) 1982;164:315–330. doi: 10.1007/BF00315754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters T., Dildrop R., Ausmeier K., Ruther U., Dildrop R., Ausmeier K., Ruther U., Ausmeier K., Ruther U., Ruther U. Organization of mouse Iroquois homeobox genes in two clusters suggests a conserved regulation and function in vertebrate development. Genome Res. 2000;10:1453–1462. doi: 10.1101/gr.144100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piscione T.D., Wu M.Y., Quaggin S.E., Wu M.Y., Quaggin S.E., Quaggin S.E. Expression of Hairy/Enhancer of Split genes, Hes1 and Hes5, during murine nephron morphogenesis. Brain Res. Gene Expr. Patterns. 2004;4:707–711. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubera I., Poujeol C., Bertin G., Hasseine L., Counillon L., Poujeol P., Tauc M., Poujeol C., Bertin G., Hasseine L., Counillon L., Poujeol P., Tauc M., Bertin G., Hasseine L., Counillon L., Poujeol P., Tauc M., Hasseine L., Counillon L., Poujeol P., Tauc M., Counillon L., Poujeol P., Tauc M., Poujeol P., Tauc M., Tauc M. Specific Cre/Lox recombination in the mouse proximal tubule. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2004;15:2050–2056. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000133023.89251.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saulnier D.M., Ghanbari H., Brandli A.W., Ghanbari H., Brandli A.W., Brandli A.W. Essential function of Wnt-4 for tubulogenesis in the Xenopus pronephric kidney. Dev. Biol. 2002a;248:13–28. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saulnier D.M., Ghanbari H., Brändli A.W., Ghanbari H., Brändli A.W., Brändli A.W. Essential function of Wnt-4 for tubulogenesis in the Xenopus pronephric kidney. Dev. Biol. 2002b;248:13–28. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxén L. Organogenesis of the kidney. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Soufan A.T., van den Hoff M.J., Ruijter J.M., de Boer P.A., Hagoort J., Webb S., Anderson R.H., Moorman A.F., van den Hoff M.J., Ruijter J.M., de Boer P.A., Hagoort J., Webb S., Anderson R.H., Moorman A.F., Ruijter J.M., de Boer P.A., Hagoort J., Webb S., Anderson R.H., Moorman A.F., de Boer P.A., Hagoort J., Webb S., Anderson R.H., Moorman A.F., Hagoort J., Webb S., Anderson R.H., Moorman A.F., Webb S., Anderson R.H., Moorman A.F., Anderson R.H., Moorman A.F., Moorman A.F. Reconstruction of the patterns of gene expression in the developing mouse heart reveals an architectural arrangement that facilitates the understanding of atrial malformations and arrhythmias. Circ. Res. 2004;95:1207–1215. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000150852.04747.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taelman V., Van Campenhout C., Solter M., Pieler T., Bellefroid E.J., Van Campenhout C., Solter M., Pieler T., Bellefroid E.J., Solter M., Pieler T., Bellefroid E.J., Pieler T., Bellefroid E.J., Bellefroid E.J. The Notch-effector HRT1 gene plays a role in glomerular development and patterning of the Xenopus pronephros anlagen. Development. 2006;133:2961–2971. doi: 10.1242/dev.02458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner D.L., Weintraub H., Weintraub H. Expression of achaete-scute homolog 3 in Xenopus embryos converts ectodermal cells to a neural fate. Genes & Dev. 1994;8:1434–1447. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.12.1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban A.E., Zhou X., Ungos J.M., Raible D.W., Altmann C.R., Vize P.D., Zhou X., Ungos J.M., Raible D.W., Altmann C.R., Vize P.D., Ungos J.M., Raible D.W., Altmann C.R., Vize P.D., Raible D.W., Altmann C.R., Vize P.D., Altmann C.R., Vize P.D., Vize P.D. FGF is essential for both condensation and mesenchymal–epithelial transition stages of pronephric kidney tubule development. Dev. Biol. 2006;297:103–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.04.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vainio S., Lin Y., Lin Y. Coordinating early kidney development: Lessons from gene targeting. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2002;3:533–543. doi: 10.1038/nrg842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vize P.D. The chloride conductance channel ClC-K is a specific marker for the Xenopus pronephric distal tubule and duct. Brain Res. Gene Expr. Patterns. 2003;3:347–350. doi: 10.1016/s1567-133x(03)00032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vize P.D., Woolf A.S., Bard J.B.L., Woolf A.S., Bard J.B.L., Bard J.B.L. The kidney: From normal development to congenital disease. Academic; San Diego, CA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.H., Simcox A., Campbell G., Simcox A., Campbell G., Campbell G. Dual role for Drosophila epidermal growth factor receptor signaling in early wing disc development. Genes & Dev. 2000;14:2271–2276. doi: 10.1101/gad.827000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P., Pereira F.A., Beasley D., Zheng H., Pereira F.A., Beasley D., Zheng H., Beasley D., Zheng H., Zheng H. Presenilins are required for the formation of comma- and S-shaped bodies during nephrogenesis. Development. 2003;130:5019–5029. doi: 10.1242/dev.00682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., Vize P.D., Vize P.D. Proximo—distal specialization of epithelial transport processes within the Xenopus pronephric kidney tubules. Dev. Biol. 2004;271:322–338. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]