Abstract

The oxidative-stress-responsive kinase 1 (OSR1) and the STE20/SPS1-related proline/alanine-rich kinase (SPAK) are key enzymes in a signalling cascade regulating the activity of Na+/K+/2Cl− co-transporters (NKCCs) in response to osmotic stress. Both kinases have a conserved carboxy-terminal (CCT) domain, which recognizes a unique peptide (Arg-Phe-Xaa-Val) motif present in OSR1- and SPAK-activating kinases (with-no-lysine kinase 1 (WNK1) and WNK4) as well as its substrates (NKCC1 and NKCC2). Here, we describe the structural basis of this recognition event as shown by the crystal structure of the CCT domain of OSR1 in complex with a peptide containing this motif, derived from WNK4. The CCT domain forms a novel protein fold that interacts with the Arg-Phe-Xaa-Val motif through a surface-exposed groove. An intricate web of interactions is observed between the CCT domain and an Arg-Phe-Xaa-Val motif-containing peptide derived from WNK4. Mutational analysis shows that these interactions are required for the CCT domain to bind to WNK1 and NKCC1. The CCT domain structure also shows how phosphorylation of a Ser/Thr residue preceding the Arg-Phe-Xaa-Val motif results in a steric clash, promoting its dissociation from the CCT domain. These results provide the first molecular insight into the mechanism by which the SPAK and OSR1 kinases specifically recognize their upstream activators and downstream substrates.

Keywords: Gordon syndrome, NKCC1, SPAK, WNK1, WNK4

Introduction

The oxidative-stress-responsive kinase 1 (OSR1) and the STE20/SPS1-related proline/alanine-rich kinase (SPAK) were originally identified by their ability to interact and stimulate the activity of Na+/K+/2Cl− co-transporter (NKCC1) in a signalling pathway that protects cells from hyperosmotic stress (Dowd & Forbush, 2003; Piechotta et al, 2003). Interest in the SPAK and OSR1 enzymes increased after the discovery that they were phosphorylated and activated by the WNK1 (with-no-lysine kinase 1) and WNK4 protein kinases (Moriguchi et al, 2005; Vitari et al, 2005; Anselmo et al, 2006; Zagórska et al, 2007), the genes of which are mutated in patients suffering from an inherited hypertension and hyperkalaemia disorder, called Gordon syndrome (Wilson et al, 2001). OSR1 and SPAK are 68% identical in sequence; they consist of an amino-terminal kinase catalytic domain and terminate in a unique 92-amino-acid sequence called the conserved carboxy-terminal (CCT) domain (Vitari et al, 2006). WNK1 and WNK4 protein kinases activate the SPAK and OSR1 protein kinases by phosphorylating them at an activation loop threonine (Thr) residue (Vitari et al, 2005; Zagórska et al, 2007).

The CCT domains of OSR1 and SPAK are 79% identical at the sequence level, and are also highly conserved in orthologues of these enzymes in Caenorhabditis elegans, Drosophila and Xenopus. The CCT domain bears no similarity to sequences found in other proteins. Previous work has suggested that the CCT domain might have a specific docking site for the Arg-Phe-Xaa-Val (RFXV) sequence motifs located in the WNK1 and WNK4 activators (Moriguchi et al, 2005; Anselmo et al, 2006; Gagnon et al, 2006; Vitari et al, 2006) and the NKCC1/NKCC2 substrates (Piechotta et al, 2003). It has also been suggested that phosphorylation of Ser 1261 in WNK1, adjacent to an RFXV motif, might induce the dissociation of SPAK and OSR1 from WNK1 after WNK1 activation by hyperosmotic stress (Zagórska et al, 2007). However, it is not yet clear where the peptide-binding site is located, what the nature of the peptide–CCT domain interaction is and how this interaction might be modulated by phosphorylation. Here, we describe a structural analysis of the CCT domain in complex with an RFXV-motif-containing peptide derived from WNK4, which shows the elaborate molecular mechanism by which the CCT domain recognizes its substrates and activators.

Results And Discussion

The CCT domain of OSR1 adopts a novel fold

Sequence alignment of human OSR1 and SPAK, and their metazoan orthologues, shows a relatively conserved kinase domain, followed by an unconserved region of variable length and then the CCT domain. A construct covering the CCT domain (residues 434–527) readily yielded soluble expression in Escherichia coli and diffraction quality crystals. From a uranium derivative, a single-wavelength anomalous dispersion experiment produced phases to a resolution of 2.25 Å, which were subsequently extended to 1.95 Å. Owing to significant disorder in some of the loops, refinement of this structure did not progress beyond a model with relatively high R-factors (R=0.29, Rfree=0.35). In an attempt to obtain a different crystal form and study how OSR1 interacts with RFXV motifs on both its activators (that is, the WNKs) and its substrates (that is, the NKCCs), the CCT domain was also crystallized with a GRFQVT peptide derived from human WNK4 (residues from glycine (Gly) 1003 to Thr 1008). Crystals of the CCT domain–GRFQVT peptide complex grew under similar conditions and in the same space group (but with different unit cell dimensions) as the uncomplexed (apo) CCT domain (Table 1). The structure of the peptide complex was solved by molecular replacement using the apo CCT domain structure and refined to 1.7 Å resolution, resulting in a model with good R-factors and stereochemistry (Table 1).

Table 1.

Details of data collection and structure refinement

| CCT apo | CCT | CCT peptide | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beamline | BM-14 | BM-14 | Rotating anode |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.954 | 0.72 | 1.54 |

| Space group | P21 | P21 | P21 |

| Unit cell (Å) | a=48.27 | a=48 | a=31.46 |

| b=142.84 | b=142.46 | b=52.75 | |

| c=52.68 | c=52.47 | c=59.27 | |

| β=90.2° | β=90.3° | β=103.23° | |

| Resolution (Å) | 20.0–1.95 (2.02–1.95) | 20.0–2.25 (2.33–2.25) | 20.0–1.7 (1.76–1.70) |

| Observed reflections | 165,852 | 496,986 | 68,557 |

| Unique reflections | 52,512 | 33,347 | 20,989 |

| Redundancy | 3.2 (2.7) | 7.6 (6.2) | 3.4 (3.2) |

| Completeness (%) | 98.7 (89.6) | 99.7 (98.3) | 94.8 (90.5) |

| Rmerge (%) | 5.3 (42.1) | 5 (40.6) | 4 (31.1) |

| I/σI | 25.2 (2.2) | 26.8 (3.4) | 33.1 (4.9) |

| Rcryst | 0.20 | ||

| Rfree | 0.24 | ||

| Number of groups | |||

| Protein residues | 192 | ||

| Water | 329 | ||

| U sites | 6 | ||

| Wilson B (Å2) | 24.9 | ||

| 〈B〉 protein (Å2) | 22.8 | ||

| 〈B〉 water (Å2) | 28.7 | ||

| R.m.s.d. from ideal geometry | |||

| Bond length (Å) | 0.013 | ||

| Bond angle (deg) | 1.54 | ||

| Values within parentheses are for the highest resolution shell. All measured data were included in structure refinement. CCT, conserved carboxy-terminal. | |||

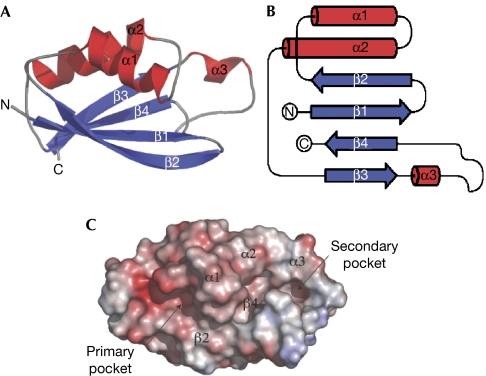

The structure of the CCT domain consists of four antiparallel β-strands (β1–β4) packed against two large α-helices (α1 and α2) and a small α-helix (α3) (Fig 1A,B). The N-terminal residues of the CCT domain fold into β1 followed by β2 after a short loop. The polypeptide chain then forms the α1, which precedes the α2 helix that spans the entire length of the molecule. A short loop leads to β3, followed by a larger loop, in which the short α3 is located, and the CCT domain fold terminates with β4, placing the C terminus near the N-terminal residue (12 Å; Fig 1A,B). Consistent with sequence alignments suggesting that the CCT domain is unique to the OSR1 and SPAK kinases, comparison of its structure with all known protein structures on the DALI server (Holm & Sander, 1993) showed no marked similarities with other protein folds. We have called this the SPOC (SPak/Osr1 C terminus) fold.

Figure 1.

Overall structure of the conserved carboxy-terminal domain. (A) Ribbon representation of CCT domain of OSR1 (residues 434–527) coloured in blue and red (β-strands and α-helices, respectively). The secondary structural elements are labelled as in the text. (B) Topology diagram of the CCT domain of OSR1 coloured as in (A). (C) Surface representation of the CCT domain of OSR1 coloured according to the electrostatic charge (blue areas (+9 kT) represent highly positively charged residues and the red areas (−9 kT) represent highly negatively charged residues). The location of the secondary structural elements is labelled, and also the location of the primary RFXV-motif-binding site and the secondary-surface-exposed groove of unknown function. CCT, conserved carboxy-terminal; OSR1, oxidative-stress-responsive kinase 1; RFXV, Arg-Phe-Xaa-Val.

The main structural feature of the SPOC fold is the stacking of helices α1 and α2 against the four β-strands (Fig 1C). This interaction is based on a hydrophobic core formed by residues valine (Val) 464, leucine (Leu) 468 and Leu 473 from α1 and residues Val 482 and Leu 486 from α2, packing against a hydrophobic patch formed by a tetra-leucine stretch (Leu 436, Leu 438, Leu 440 and Leu 524) of the β-sheet. Analysis of the molecular surface indicates the presence of an elongated, negatively charged groove (the ‘primary' pocket; Fig 1C) formed by the interface between α1 and β2 and a hydrophobic pocket (the ‘secondary' pocket; Fig 1C) formed by the large loop connecting α3 to β4.

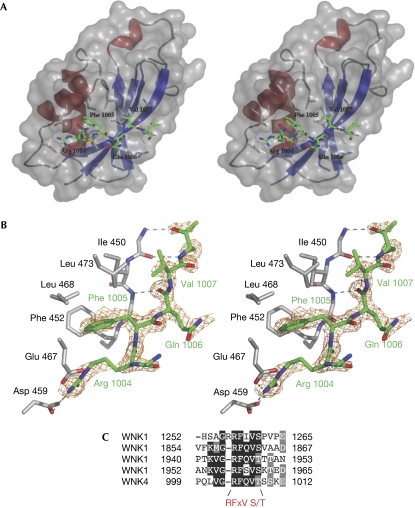

Structure of the CCT domain–RFXV motif complex

The apo CCT domain crystal contains eight independent molecules in the asymmetrical unit, whereas the peptide complex crystal contains only two. Superposition of the partly refined apo CCT domain and the peptide complex shows that these adopt similar conformations (r.m.s.d. on all Cα atoms=0.68 Å). Thus, binding of the GRFQVT peptide to the CCT domain does not induce a marked conformational change in the overall structure of the CCT domain. Interestingly, however, the loops (507–512 and 494–497) that were disordered in the partly refined apo structure and prevented proper refinement are ordered in the complex.

The GRFQVT peptide binds to the solvent-exposed ‘primary' pocket, formed by the interface between α1 and β2 (Fig 2A). Numerous interactions between the CCT domain and peptide are observed. The peptide backbone between Val 1007 and Thr 1008 on the peptide forms β-sheet hydrogen bonds with backbone atoms of residues 449–451 located on β2 of the CCT domain. Arginine (Arg) 1004 of the peptide makes ionic interactions with aspartic acid (Asp) 459 located in the loop between β2 and α1 (distance 3.0 Å) and glutamic acid (Glu) 467, which projects from α1 (distance 2.8 Å) (Fig 2A,B). This exploits the charge complementarity of the peptide (positively charged) and the ‘primary' pocket on the CCT domain (negatively charged; Fig 1C). Phenylalanine (Phe) 1005 of the peptide sits in a large, shallow, hydrophobic pocket formed by Phe 452 on β2, as well as Leu 468, alanine (Ala) 471 and Leu 473 that are located on α1 (Fig 2). Val 1007 also forms hydrophobic stacking with isoleucine (Ile) 450 (Fig 2). Strikingly, glutamine (Gln) 1006 on the peptide faces away from the CCT domain and does not interact with the protein. This is consistent with previous work showing that mutation of the Arg, Phe or Val residue, but not the Gln residue, prevented binding of the WNK4 peptide to the CCT domain (Vitari et al, 2006).

Figure 2.

Molecular interaction of the RFXV peptide with the conserved carboxy-terminal domain of OSR1. (A) Stereo view of the CCT domain of OSR1 (residues 434–527) coloured in blue and red (β-strands and α-helices) in complex with the GRFQVT WNK4-derived peptide coloured in green. Asn 448, Asp 449, Ile 450, Phe 452, Asp 459, Glu 467, Ala 471 and Leu 473 that make up the RFXV-peptide-binding groove are shown in a stick representation. (B) Detailed stick representation of the molecular interaction between the CCT residues (grey) and the GRFQVT peptide (green). The WNK4 peptide encompassing the RFQV motif is shown in stick representation (green) with an Fo−Fc electron density (orange) contoured at the 2.5σ level. (C) Multiple sequence alignment of human WNK1 and WNK4 RFXV motifs. Numbering is according to the sequence of human WNK1 and WNK4. Ala, alanine; Arg, arginine; Asn, asparagine; Asp, aspartic acid; CCT, conserved carboxy-terminal; Gln, glutamine; Glu, glutamic acid; Ile, isoleucine; Leu, leucine; OSR1, oxidative-stress-responsive kinase 1; Phe, phenylalanine; RFXV, Arg-Phe-Xaa-Val; Val, valine; WNK, with-no-lysine kinase 1; WT, wild type.

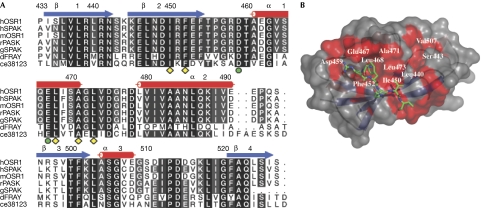

Sequence conservation in the peptide-binding pocket

Comparison of the CCT domain sequences of OSR1 and SPAK from metazoan organisms shows a high degree of sequence conservation of this domain (Fig 3A). Moreover, all the CCT domain residues that interact with the RFXV motif are identical in OSR1 and SPAK sequences (Fig 3A). This indicates that the mechanism by which the CCT domain recognizes RFXV motifs in OSR1 activators and substrates has been preserved during evolution. Although the sequence conservation is evenly distributed throughout the CCT domain sequence (Fig 3A), analysis of the sequence conservation in the context of the CCT domain crystal structure shows a strikingly ordered pattern of clustered, conserved, solvent-exposed residues. The conservation is concentrated not only within the RFXV-peptide-binding groove, but also extends in a snake-like pattern over the surface, ending in the ‘secondary' pocket of the CCT domain formed by the loop connecting α3 to β4 (Fig 3B).

Figure 3.

The RFXV recognition mechanism is evolutionarily conserved. (A) Multiple sequence alignment of human OSR1 and SPAK kinases and their orthologues in the indicated species. Secondary structural elements are indicated and numbering is according to human OSR1. (B) The protein surface of the CCT domain is shown in two different colours to reflect the sequence conservation of OSR1 with the orthologues. Grey represents unconserved residues and red identical residues. The stick representation of the peptide (green) is also shown. CCT, conserved carboxy-terminal; ce, Caenorhabditis elegans; d, Drosophila; g, Gallus gallus; h, human; m, mouse; OSR1, oxidative-stress-responsive kinase 1; r, rat; RFXV, Arg-Phe-Xaa-Val; SPAK, proline/alanine-rich kinase.

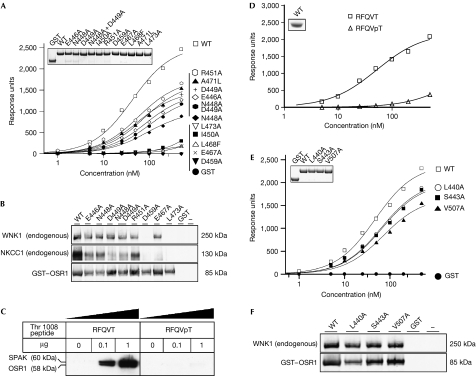

Conserved residues interact with the RFXV motif

To probe further the significance of the conserved residues on the CCT domain and their contribution to the binding of the peptide, several of these residues were mutated. The effect of these mutations on the ability of the isolated CCT domain to bind to a biotinylated peptide encompassing the RFQV motif of WNK4 was then evaluated using a quantitative surface plasmon resonance-based binding assay. The results confirmed that the isolated wild-type CCT domain bound with high affinity to the WNK4-derived peptide and that binding was prevented by individual mutation of five residues (Ile 450, Asp 459, Glu 467, Leu 468 and Leu 473) and considerably inhibited by mutation of five other residues (Glu 446, Gln 448, Asp 449, Arg 451 and Ala 471; Fig 4A). These mutations show that the electrostatic interactions between the domain and Arg 1004 on the peptide are essential, as well as the hydrophobic interactions originating from Phe 1005 and Val 1007 on the peptide. We also evaluated how these CCT mutations affected the ability of the full-length OSR1 enzyme overexpressed in cells from the 293 cell line to interact with endogenously expressed WNK1 and NKCC1 (Fig 4B). The results showed that mutation of Asp 459 and Leu 473 completely inhibited binding of full-length OSR1 to WNK1 and NKCC1. By contrast, the other mutants tested still had near-normal ability to bind to WNK1, but reduced ability to bind to NKCC1. As WNK1 has four RFXV motifs and NKCC1 only two RFXV motifs, it is possible that the availability of multiple binding sites on WNK1 enables it to interact with CCT domain mutants with reduced RFXV motif affinity more potently than NKCC1. These observations indicate that to completely ablate CCT domain function in future studies of the biological role of the CCT domain, the Asp459Ala or Leu473Ala mutant should be used.

Figure 4.

Analysis of binding properties of the conserved carboxy-terminal domain mutants. (A,D,E) The binding of bacterially expressed wild-type OSR1 CCT domain and the OSR1 CCT domain mutants (residues 434–527) to a biotinylated RFQV-containing peptide derived from WNK4 (biotin-SEEGKPQLVGRFQVTSSK) was analysed by surface plasmon resonance. In (D), the phosphorylated biotin-SEEGKPQLVGRFQVpTSSK peptide called RFQVpT was compared with the equivalent non-phosphorylated peptide called RFQVT. The analysis was carried out over a range of protein concentration (1–500 nM) and the response level at steady state was plotted against the log of the protein concentration. The inset shows the similar level of wild type and mutant forms of recombinant protein used for this analysis. (B,F) 293 cells were transfected with GST-tagged forms of wild type and indicated mutants of the full-length OSR1 kinase (residues 1–527). At 36 h after transfection, cell were lysed and subjected to affinity purification with glutathione–Sepharose. Immunoblot analysis was used with a GST antibody to monitor the level of wild-type and mutants expression and anti-WNK1 or anti-NKCC1 to detect association of endogenous WNK1 and NKCC1 with the overexpressed GST–OSR1. (C) The indicated amounts of phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated peptide were conjugated to streptavidin–Sepharose and incubated with 1 mg of 293 cell lysate. After isolation and washes of the beads, the samples were electrophoresced on a polyacrylamide gel and immunoblotted with an antibody recognizing both SPAK and OSR1. CCT, conserved carboxy-terminal; GST, glutathione-S-transferase; NKCC, Na+/K+/2Cl− co-transporter; OSR1, oxidative-stress-responsive kinase 1; SPAK, proline/alanine-rich kinase; WNK1, with-no-lysine kinase 1; WT, wild type.

Phosphorylation and inhibition of binding to the CCT domain

Many of the RFXV motifs found in WNK1 and WNK4 and other known or putative SPAK- and OSR1-binding protein are preceded by a serine or threonine residue (Fig 2C; Delpire & Gagnon, 2006). The WNK4 peptide that was crystallized with the CCT domain of OSR1 also contains a threonine residue located after the RFXV motif (Thr 1008; Fig 2) in an equivalent position to Ser 1261 in WNK1. Analysis of the OSR1–CCT domain structure indicates that phosphorylation of the Thr 1008 residue would result in a steric clash with the backbone of the CCT domain, thereby inhibiting binding of this peptide to the CCT domain. Consistent with this, we found that a biotinylated RFXV-pT in which the threonine residue equivalent to Thr 1008 in WNK4 is phosphorylated, when conjugated to streptavidin–Sepharose, failed to interact with endogenously expressed SPAK and OSR1 in 293 cell lysates under conditions in which the dephosphorylated peptide bound strongly to these enzymes (Fig 4C). Using a quantitative surface plasmon resonance-based binding assay, we also found that the phosphorylated RFXV-pT WNK4 peptide binds to the isolated OSR1–CCT domain with markedly lower affinity than the dephosphorylated peptide (Fig 4D). The results provide further evidence that the interaction of RFXV motifs with the CCT domain might be regulated by phosphorylation of the serine/threonine residue that frequently follows this motif on WNK1 and WNK4 (Fig 2C), as well as RFXV motif-containing proteins suggested to interact with SPAK and OSR1 (Delpire & Gagnon, 2006).

Conserved residues in the ‘secondary' pocket

As noted previously, there is significant sequence conservation beyond the RFXV-peptide-binding groove and it is possible that these areas also participate in binding of residues beyond the RFXV motif in the WNKs and/or NKCCs. To investigate the potential involvement of the conserved residues in the ‘secondary' pocket in the interaction with WNK1 and/or NKCC1, residues Leu 440, Ser 443 and Val 507, which line this pocket, were mutated, and the effect of these mutations on the binding ability of the CCT domain was studied. These mutations showed only minor effects on binding of the CCT domain to the WNK4 peptide or binding of full-length OSR1 to endogenous WNK1 and NKCC1 in 293 cells, suggesting that these residues are not essential for binding OSR1 activators and substrates (Fig 4E,F).

Conclusion

The structure of the CCT domain represents a novel protein fold that we have called the SPOC fold and reinforces the concept that one of its roles is to recognize RFXV motifs. Our findings show the molecular interactions made between the arginine, phenylalanine and valine residues and the CCT domain, accounting for the interactions that OSR1 and SPAK have with WNK1/WNK4 and NKCC1/NKCC2.

Interestingly, protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) interacts with regulatory subunits by recognizing an RVXF motif in these proteins (Johnson et al, 1996), not dissimilar to the RFXV motif recognized by the CCT domain. The crystal structure of PP1 in complex with an RVXF peptide motif has been solved (Egloff et al, 1997) and when compared with the CCT–WNK4 peptide complex, some similar features emerge despite no structural similarity between PP1 and the CCT domain. The RVXF peptide binds to PP1, with the arginine, valine and phenylalanine residues forming interactions with a surface-exposed pocket on PP1, with the third (X) residue pointing away from the PP1 surface. A detailed database search using the PP1 RVXF-binding motif as queries identified several unknown PP1 interactors (Meiselbach et al, 2006). A similar approach could be applied to OSR1 and SPAK RFXV-binding motif to identify novel binding partners.

For protein-phosphatase-interacting regulatory subunits such as GM, phosphorylation of the underlined serine residue in the PP1-binding RVSF-motif triggers its dissociation from PP1 (Hubbard & Cohen, 1993). Similarly, our data with the RFXV-motif-containing peptide located next to Thr 1008 of WNK4 (Figs 2C, 4C,D) shows that phosphorylation of the threonine/serine residue following the RFXV motif inhibits binding to the CCT domain, most probably caused by a steric clash between the phosphate group and the backbone of the CCT domain. Although we have not been able to detect any endogenous phosphorylation on the WNK4 Thr 1008, previous work showed the presence of an in vivo phosphorylation site on an equivalent WNK1 residue (Zagórska et al, 2007). Phosphorylation of the WNK1 Ser 1261 results in weaker binding to the OSR1 and SPAK kinases (Zagórska et al, 2007). In the case of WNK1, phosphorylation of Ser 1261 is induced by hyperosmotic stress (Zagórska et al, 2007). It is possible that, in non-stressed cells, inactive WNK1 exists in a complex with SPAK and OSR1, and after hyperosmotic stress, WNK1 phosphorylates and activates SPAK and OSR1. Ser 1261 is then phosphorylated by an as-yet-unknown kinase, inducing dissociation of WNK1 from SPAK and OSR1, which are then free to interact with their RFXV-motif-containing substrates.

The elucidation of the structural basis by which SPAK and OSR1 interact with RFXV motifs within their activators and substrates might provide a basis for rational design of peptide mimics that inhibit the WNK pathway as an alternative to ATP competitive inhibitors. Such drugs might be useful in the treatment of hypertension.

Methods

Cloning, expression and crystallization of OSR1 (434–527). A fragment of OSR1 (434–527) was cloned into a pGex expression vector (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA). E. coli cells were transformed with the OSR1 (434–527) vector and were grown at 37°C until the A600 reached 1. Isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG, 0.15 mM) was then added and the culture was grown at 26°C for 18 h. OSR1 (434–527) was glutathione-S-transferase (GST) affinity purified using the standard protocol and the affinity tag was removed after incubation with PreScission protease. OSR1 (434–527) was further purified on a Superdex-75 26/60 column equilibrated against 25 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5) and 1 mM dithiothreitol. The OSR1 (434–527) mutants used in BiaCore (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) analysis were expressed and purified using an identical protocol and eluted as GST-fused protein. Pure OSR1 (434–527) protein was concentrated to 5 mg/ml and vapour diffusion crystallization experiments were set up by mixing 0.9 μl of protein and 0.9 μl of mother liquor (0.2 M ammonium acetate, 0.1 M sodium acetate (pH 4.6) and 25% polyethylene glycol (PEG 4000). To obtain WNK4 peptide complex crystals, OSR1 (434–527) protein at 5 mg/ml was mixed with a threefold molar excess of WNK4 peptide and incubated on ice for 30 min. Crystals were grown by mixing 0.9 μl of protein with an equal volume of mother liquor (0.2 M sodium acetate, 0.1 M Tris (pH 8.5) and 25% PEG 4000).

Data collection, structure solution and refinement. The crystals were cryoprotected by a 5 s immersion in mother liquor and 15% (v/v) PEG 400 and then frozen in a nitrogen cryostream. Crystals used for phasing were soaked in mother liquor containing 5 mM uranyl acetate for approximately 18 h and cryoprotected as above.

A 2.25 Å single-wavelength anomalous dispersion data set was collected from crystals soaked in uranyl acetate (Table 1). Six uranium sites were located by SHELX (Sheldrick & Schneider, 1997), as implemented in the HKL2MAP package (Pape & Schneider, 2004). With the help of FFFear (Collaborative Computational Project, 1994), we detected helices and strands belonging to a single molecule, and subsequently by using MOLREP (Vagin & Teplyakov, 1997) located the eight molecules in the crystal asymmetrical unit and found the non-crystallographic symmetry relations. Solvent flattening, phase extension to 1.95 Å and eightfold averaging were then carried out with DM (Cowtan & Main, 1998). WarpNtrace (Perrakis et al, 1999) was then able to build 548 out of 768 possible residues, covering eight molecules in the asymmetrical unit. Iterative model building using Coot (Emsley & Cowtan, 2004) and refinement with REFMAC (Murshudov et al, 1997) then produced a partly refined model with relatively high R-factors (R=0.29, Rfree=0.35).

Diffraction data of the OSR1 (434–527)–WNK4 peptide crystals were collected on a rotating anode to 1.7 Å resolution (Table 1). Molecular replacement was carried out using MOLREP (Vagin & Teplyakov, 1997) and the partly refined apo structure used as a search model. Refinement was initiated using Coot (Emsley & Cowtan, 2004). All figures were made with PyMOL (www.pymol.org).

BiaCore analysis. Binding of peptides to mutant forms of the CCT domain was analysed in a BiaCore 3000 system as described previously (Vitari et al, 2006).

Affinity purification of SPAK and OSR1 from 293 cells. Analysis of the binding properties of the OSR1 mutants in vivo was tested in 293 cells as described previously (Vitari et al, 2006; Zagórska et al, 2007).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr A. Vitari for help and thoughtful discussion and the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (Grenoble, France) for beam time at BM14. D.M.F.v.A. was supported by a Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellowship and a Lister Research Prize. J.G. was supported by a special Fellowship from Dundee Camperdown Lodge. We are grateful to the Association for International Cancer Research, Diabetes UK, the Medical Research Council and the Moffat Charitable Trust for financial support. The coordinates and structure factors have been deposited with the Protein Data Bank entry 2VS3.

References

- Anselmo AN, Earnest S, Chen W, Juang YC, Kim SC, Zhao Y, Cobb MH (2006) WNK1 and OSR1 regulate the Na+, K+, 2Cl− cotransporter in HeLa cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 10883–10888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowtan K, Main P (1998) Miscellaneous algorithms for density modification. Acta Crystallogr D 54: 487–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delpire E, Gagnon KB (2006) Genome-wide analysis of SPAK/OSR1 binding motifs. Physiol Genomics 28: 223–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowd BF, Forbush B (2003) PASK (proline-alanine-rich STE20-related kinase), a regulatory kinase of the Na–K–Cl cotransporter (NKCC1). J Biol Chem 278: 27347–27353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egloff MP, Johnson DF, Moorhead G, Cohen PT, Cohen P, Barford D (1997) Structural basis for the recognition of regulatory subunits by the catalytic subunit of protein phosphatase 1. EMBO J 16: 1876–1887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Cowtan K (2004) Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D 60: 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon KB, England R, Delpire E (2006) Volume sensitivity of cation-Cl- cotransporters is modulated by the interaction of two kinases: Ste20-related proline-alanine-rich kinase and WNK4. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 290: C134–C142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm L, Sander C (1993) Protein structure comparison by alignment of distance matrices. J Mol Biol 233: 123–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard MJ, Cohen P (1993) On target with a new mechanism for the regulation of protein phosphorylation. Trends Biochem Sci 18: 172–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DF, Moorhead G, Caudwell FB, Cohen P, Chen YH, Chen MX, Cohen PT (1996) Identification of protein-phosphatase-1-binding domains on the glycogen and myofibrillar targeting subunits. Eur J Biochem 239: 317–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiselbach H, Sticht H, Enz R (2006) Structural analysis of the protein phosphatase 1 docking motif: molecular description of binding specificities identifies interacting proteins. Chem Biol 13: 49–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriguchi T, Urushiyama S, Hisamoto N, Iemura S, Uchida S, Natsume T, Matsumoto K, Shibuya H (2005) WNK1 regulates phosphorylation of cation-chloride-coupled cotransporters via the STE20-related kinases, SPAK and OSR1. J Biol Chem 280: 42685–42693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ (1997) Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D 53: 240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape T, Schneider TR (2004) HKL2MAP: a graphical user interface for macromolecular phasing with SHELX. J Appl Crystallogr 37: 843–844 [Google Scholar]

- Perrakis A, Morris R, Lamzin VS (1999) Automated protein model building combined with iterative structure refinement. Nat Struct Biol 6: 458–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piechotta K, Garbarini N, England R, Delpire E (2003) Characterization of the interaction of the stress kinase SPAK with the Na+–K+–2Cl− cotransporter in the nervous system: evidence for a scaffolding role of the kinase. J Biol Chem 278: 52848–52856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick GM, Schneider TR (1997) SHELXL: high resolution refinement. Methods Enzymol 277: 319–343 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vagin A, Teplyakov A (1997) MOLREP: an automated program for molecular replacement. J Appl Crystallogr 30: 1022–1025 [Google Scholar]

- Vitari AC, Deak M, Morrice NA, Alessi DR (2005) The WNK1 and WNK4 protein kinases that are mutated in Gordon's hypertension syndrome phosphorylate and activate SPAK and OSR1 protein kinases. Biochem J 391: 17–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitari AC, Thastrup J, Rafiqi FH, Deak M, Morrice NA, Karlsson HK, Alessi DR (2006) Functional interactions of the SPAK/OSR1 kinases with their upstream activator WNK1 and downstream substrate NKCC1. Biochem J 397: 223–231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson FH et al. (2001) Human hypertension caused by mutations in WNK kinases. Science 293: 1107–1112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zagórska A et al. (2007) Regulation of activity and localisation of the WNK1 protein kinase by hyperosmotic stress. J Cell Biol 176: 89–100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]