Abstract

Communication between neurons relies on chemical synapses and the release of neurotransmitters into the synaptic cleft. Neurotransmitter release is an exquisitely regulated membrane fusion event that requires the linking of an electrical nerve stimulus to Ca2+ influx, which leads to the fusion of neurotransmitter-filled vesicles with the cell membrane. The timing of neurotransmitter release is controlled through the regulation of the soluble N-ethylmaleimide sensitive factor attachment receptor (SNARE) proteins—the core of the membrane fusion machinery. Assembly of the fusion-competent SNARE complex is regulated by several neuronal proteins, including complexin and the Ca2+-sensor synaptotagmin. Both complexin and synaptotagmin bind directly to SNAREs, but their mechanism of action has so far remained unclear. Recent studies revealed that synaptotagmin-Ca2+ and complexin collaborate to regulate membrane fusion. These compelling new results provide a molecular mechanistic insight into the functions of both proteins: complexin ‘clamps' the SNARE complex in a pre-fusion intermediate, which is then released by the action of Ca2+-bound synaptotagmin to trigger rapid fusion.

Keywords: membrane fusion, synaptic vesicle, SNARE, synaptotagmin, complexin

Introduction

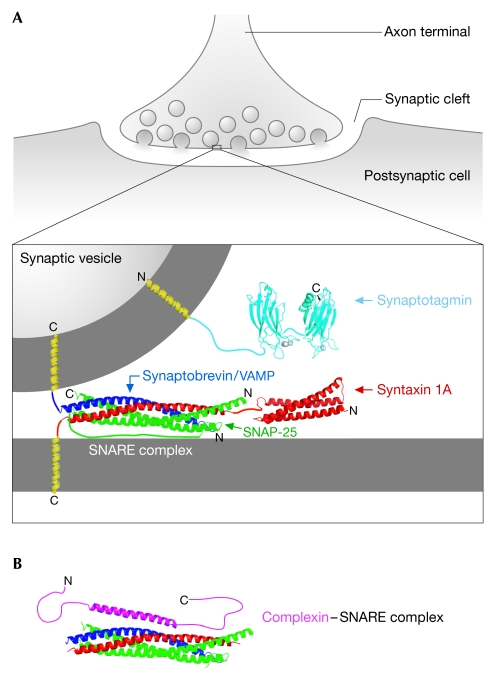

In eukaryotic cells, membrane-bound vesicles are used to transport cargo between functionally distinct intracellular compartments and to the plasma membrane. In neurons, the presynaptic nerve terminal contains synaptic vesicles that are filled with neurotransmitters (Fig 1A). The synaptic vesicles are tightly clamped at the presynaptic membrane to prevent premature membrane fusion in the absence of Ca2+. After the arrival of an action potential, Ca2+ enters through voltage-gated channels and neurotransmitter release occurs very rapidly, usually in less than a millisecond.

Figure 1.

Structures of proteins required for the fast, Ca2+-stimulated release of neurotransmitters. (A) The SNARE complex (Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID , Sutton et al, 1998) and the C2A and C2B domains of synaptotagmin I (PDB IDs , Shao et al, 1998; and , Fernandez et al, 2001, respectively) are required at sites of synaptic vesicle fusion on the presynaptic plasma membrane. (B) Complexin bound to the SNARE complex (PDB ID , Chen et al, 2002). The transmembrane domains and unstructured regions are modelled in the figure. Amino- and carboxy-terminal ends of each protein are indicated. SNAP-25, synaptosome-associated protein of 25kDa; VAMP, vesicle-associated membrane protein.

Much of the basic vesicle transport and fusion machinery is conserved in all eukaryotes. The core of the membrane fusion machinery is the soluble N-ethylmaleimide sensitive factor attachment receptor protein (SNARE) complex, which is regulated by several conserved proteins, including N-ethylmaleimide sensitive factor (NSF), α-soluble NSF attachment protein (α-SNAP), Sec1/Munc18, Rab GTPases, and tethering proteins (for a review, see Waters & Hughson, 2000; Whyte & Munro, 2002; Bonifacino & Glick, 2004; Jahn & Scheller, 2006, and references therein); however, detailed molecular mechanisms for regulation have yet to be elucidated. Additional proteins, including synaptotagmin, complexin, Munc13, synaptophysin and tomosyn, are used in neurons to ensure that membrane fusion is both precise and rapid (Sollner, 2003; Sudhof, 2004; Brunger, 2005).

At the synapse, neurotransmitter-containing vesicles are docked—primed and ready to fuse to the presynaptic membrane—but do not fuse until the arrival of a Ca2+ signal. Two important questions in this regard are: what prevents these vesicles from premature fusion, and how does fusion occur so quickly after Ca2+ influx? One proposed mechanism is that the SNAREs are tightly clamped in a pre-fusion state, poised for Ca2+-triggered release, but not initiating membrane fusion. Two crucial regulatory proteins, synaptotagmin and complexin, are present before membrane fusion, but their individual contributions to the speed and precision of fusion are the subject of continued debate (Sollner, 2003; Yoshihara et al, 2003; Sudhof, 2004; Bai & Chapman, 2004; Brunger, 2005; Rizo et al, 2006), although recent results suggest that they cooperate to regulate neurotransmitter release (Giraudo et al, 2006; Schaub et al, 2006; Tang et al, 2006). In this way, the whole of the fusion machinery is held on the brink of fusion, but only the arrival of the Ca2+ signal can trigger the near-instantaneous activation of the process.

SNARE-mediated membrane fusion is highly regulated

SNARE proteins are an integral part of the membrane fusion machinery. Several lines of evidence implicate SNAREs in membrane fusion: structural similarity to viral membrane fusion proteins, the actions of clostridial neurotoxins, numerous genetic and cell biological experiments (for a review, see Brunger, 2005; Jahn & Scheller, 2006), and the ability of SNAREs to fuse both artificial liposomes in vitro and membranes in cell-based fusion assays (Weber et al, 1998; Hu et al, 2003; Yoon et al, 2006). SNAREs function at both constitutive and regulated stages in the secretory pathway, for example, both in the constitutive transport required for cell growth and the highly regulated release of neurotransmitters on stimulation by an action potential. They are present on vesicle (v-SNAREs) and target membranes (t-SNAREs), and form a parallel four-helical bundle complex that bridges the membranes inside the cell (Fig 1A; Sutton et al, 1998). In the neuron, the SNAREs are synaptobrevin/vesicle-associated membrane protein (VAMP) on the synaptic vesicle membrane and syntaxin 1A and synaptosome-associated protein of 25kDa (SNAP-25) on the presynaptic plasma membrane. Assembly of SNARE complexes requires exquisite spatial and temporal regulation to prevent inappropriate membrane fusion. In addition to general membrane trafficking regulators, such as Rab GTPases, Sec1/Munc18 and tethering complexes (Waters & Hughson, 2000; Whyte & Munro, 2002; Bonifacino & Glick, 2004; Jahn & Scheller, 2006), neurons use specialized regulatory proteins—that is, neither present in all eukaryotes, nor at all steps in the secretory pathway—to achieve tight Ca2+ regulation (Sollner, 2003; Sudhof, 2004; Brunger, 2005; Rizo et al, 2006).

Synaptotagmin is a Ca2+ sensor for synaptic fusion

Synaptotagmin proteins are obvious candidates to regulate SNARE-mediated fusion in response to Ca2+ influx. Synaptotagmins are a family of Ca2+-binding transmembrane proteins—with at least 16 isoforms in mammals—several of which are found in high abundance at the surface of synaptic vesicles (Yoshihara et al, 2003; Bai & Chapman, 2004; Brunger, 2005; Rizo et al, 2006; Takamori et al, 2006). More specifically, synaptotagmin I—referred to here as synaptotagmin—is the main Ca2+ sensor in neurons, where it is essential for the fast, synchronous fusion of synaptic vesicles after Ca2+ influx (Geppert et al, 1994; Fernandez-Chacon et al, 2001; Yoshihara & Littleton, 2002; Chapman, 2002).

Synaptotagmins generally consist of an amino-terminal transmembrane domain and two Ca2+-binding conserved region 2 of protein kinase C (C2) domains (Fig 1A; Shao et al, 1998; Sutton et al, 1999; Fernandez et al, 2001). The C2A and C2B domains are independently folded β-sandwich domains that cooperatively bind to Ca2+ ions and the head-group region of the membrane. The C2 domains of synaptotagmin also appear to bind to the individual t-SNAREs, the binary t-SNARE complex and ternary v-/t-SNARE complexes. These interactions occur at the carboxy-terminal, membrane-proximal regions of the SNAREs (Bai & Chapman, 2004; Brunger, 2005; Bowen et al, 2005; Dai et al, 2007; Li et al, 2007). Although synaptotagmin has been well studied, both in vivo and in vitro, many specific functional questions and debates remain, including: the molecular details of the interactions between synaptotagmin and SNARE complexes; the presence and roles of different oligomerization states of synaptotagmin; the relative importance of the C2A compared with the C2B domain; and the functional consequences of phospholipid binding (Bai & Chapman, 2004; Rizo et al, 2006). Furthermore, the molecular mechanism by which synaptotagmin-Ca2+ triggers membrane fusion is still unclear.

Complexin regulates fusion both positively and negatively

In addition to synaptotagmin, complexins—also called synaphins—are also implicated in Ca2+-regulated neurotransmitter release. Complexins are soluble, polar proteins of approximately 15–20 kDa, predominantly found in neurons (Marz & Hanson, 2002; Brunger, 2005). Elucidation of the function of complexins has been complicated by apparently conflicting data. Complexins are necessary for a positive role in synaptic vesicle fusion, as neurons lacking both complexins I and II show a marked reduction in Ca2+-evoked fast, synchronous neurotransmitter release (Reim et al, 2001). Conversely, complexin also seems to have a negative role in fusion because the injection of recombinant complexin into Aplysia nerve terminals resulted in the inhibition of evoked neurotransmitter release (Ono et al, 1998); in addition, when complexin peptides that bind to syntaxin were microinjected into the presynaptic terminals of giant squid, a marked decrease of evoked neurotransmitter release was observed (Tokumaru et al, 2001).

Although it is clear that complexin binds to SNARE complexes, this interaction is apparently independent of Ca2+. Structural studies of complexin indicate that residues 29–86 contain helical structure, the 48–70 helix binds to a groove along the preformed SNARE complex, and the N- and C-terminal ends of complexin appear to be mostly unstructured (Fig 1B; Pabst et al, 2000; Bracher et al, 2002; Chen et al, 2002). Functional studies of truncated versions of complexin indicate a requirement for both the SNARE-complex-binding residues of complexin and for residues in the N-terminal region (Xue et al, 2007). The complexin SNARE-complex-binding α-helix interacts with the membrane-proximal end of the SNARE complex, making contacts with residues on both syntaxin and synaptobrevin, but does not perturb the structure of the SNARE complex.

Synaptotagmin Ca2+ releases complexin to drive fusion

Vesicles are docked, primed and ready to fuse at the presynaptic nerve terminal before the arrival of the Ca2+ signal. In the docked state, the vesicle and plasma membrane SNARE proteins are assembled into a complex, although they do not attain a fully fusogenic state. In this regard, several important questions have remained unresolved, including: what prevents the assembled SNARE complexes from prematurely fusing the membranes in the absence of Ca2+, and how does the Ca2+ influx promote rapid fusion? Key to a mechanistic understanding of regulated membrane fusion is the ability to reconstitute fusion in ‘minimal' in vitro assays. However, so far, these fusion assays do not faithfully reproduce the situation in vivo; most are significantly slower and Ca2+-independent, suggesting the absence of crucial factors and problems with the use of artificial vesicles (Rizo et al, 2006; Jahn & Scheller, 2006). Recent studies testing synaptotagmin and complexin in these and other assays have resulted in a significant breakthrough in our understanding of how these two proteins cooperate to achieve rapid Ca2+-dependent fusion (Giraudo et al, 2006; Schaub et al, 2006; Tang et al, 2006).

These new studies suggest that the role of complexin is to clamp the SNARE complex in a pre-fusion state (Fig 2A). Complexin might achieve this function by binding to partly or fully assembled SNARE complexes, while preventing their final, fusogenic conformation. This model is consistent with the structure of the complexin–SNARE complex; complexin binds to the SNARE complex at residues near the membrane-proximal end of the complex. One prediction of this model is that the addition of complexin to an in vitro fusion assay should block fusion. Giraudo and colleagues tested this idea by modifying their cell-based fusion assay (Hu et al, 2003), in which ‘flipped' SNARE proteins are expressed on the outside of cells and promote cell–cell membrane fusion, to include complexin (Giraudo et al, 2006). They found that the addition of soluble, recombinant complexin, or a flipped glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored complexin, significantly inhibited SNARE-mediated membrane fusion. The GPI anchor was used to artificially increase the local concentration of complexin, and the release of complexin from the GPI anchor with phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C (PI-PLC) led to a markedly faster rate of fusion: minutes as opposed to hours. These results suggest that the SNARE complexes are being held by complexin in a pre-fusion, clamped intermediate state. Similar results were obtained by Schaub and colleagues using an in vitro liposome fusion assay (Schaub et al, 2006). In this assay, complexin appeared to clamp the SNAREs in a hemifusion intermediate, in which only the outer leaflet of the bilayers fused. To examine the role of complexin in vivo, Tang and colleagues expressed a chimaera of complexin fused to the N-terminus of the v-SNARE, synaptobrevin, in cultured neurons (Tang et al, 2006). This chimaera resulted in the inhibition of fast, synchronous Ca2+-triggered neurotransmitter release, indicating that artificially high local concentrations of complexin can block Ca2+-stimulated fusion in vivo.

Figure 2.

Schematic for the clamp–release model of complexin–synaptotagmin function. (A) Clamp: SNARE complexes assemble when synaptic vesicles dock at the presynaptic membrane. Complexin clamps SNARE complexes and prevents membrane fusion. (B) Intermediate state: synaptotagmin recognizes and binds to the complexin–SNARE complex in the absence of Ca2+. (C) Release: after Ca2+ influx (yellow spheres), synaptotagmin binds to both Ca2+ and membranes. This conformational change releases complexin, and the shape of the membrane-inserted, Ca2+–synaptotagmin–SNARE complex might buckle the membranes outwards to complete fusion (Martens et al, 2007). The clamped state has been proposed to be metastable or ‘superprimed' (Tang et al, 2006), perhaps by hemifusion of the membranes (Schaub et al, 2006). The molecular details of the interactions between synaptotagmin, complexin and the SNARE complex, and the conformational changes that occur on Ca2+ binding have yet to be determined.

If complexin does clamp the SNARE complex and prevent fusion, how is it released when Ca2+ is present? Complexin–SNARE interactions are Ca2+-insensitive, suggesting that a Ca2+-sensing protein must be involved; synaptotagmin seemed a likely candidate. Indeed, at physiological salt concentrations and Ca2+ levels, and in the presence of phospholipids, synaptotagmin seems to bind more tightly to SNARE complexes and displace complexin (Tang et al, 2006). However, complexin might not need to be fully released from the SNARE complexes, as Schaub and co-workers observed binding of both synaptotagmin and complexin to SNARE-complex-containing liposomes in the presence of Ca2+ (Schaub et al, 2006). This competition model is also consistent with recent data showing that the binding site on the SNARE complex for the Ca2+–synaptotagmin–phospholipid complex might partly overlap the complexin binding site (Dai et al, 2007). This model predicts that the displacement of complexin by synaptotagmin–Ca2+ would free the SNARE complexes for membrane fusion. This prediction held in both the flipped cell fusion assay and the in vitro liposome fusion assay. Cell fusion, after PI-PLC release of GPI–complexin, was further stimulated—around twofold—by the addition of flipped synaptotagmin I and Ca2+ (Giraudo et al, 2006). With the in vitro liposome fusion assay, the complexin-clamped SNARE complex intermediate was released by synaptotagmin–Ca2+ in around 10 s (Schaub et al, 2006). Similarly, addition of the synaptotagmin C2B domain released a complexin-mediated block in sperm acrosomal exocytosis (Roggero et al, 2007).

What is the nature of the pre-fusion clamped intermediate state, and how does synaptotagmin–Ca2+ release complexin? A plausible mechanistic model is that—in the absence of Ca2+—synaptotagmin recognizes and binds to the complexin–SNARE complex (Fig 2B), an idea that is consistent with experiments using near-physiological conditions (Giraudo et al, 2006; Tang et al, 2006). After formation of this intermediate, Ca2+ influx would cause synaptotagmin to bind to both Ca2+ and membranes, leading to a conformational change that would rapidly disrupt the complexin–SNARE interaction (Fig 2C). This could either be a direct effect of synaptotagmin on complexin—perhaps through the N- or C-terminal regions of complexin—or indirectly through changes in the SNARE complex structure itself. Therefore, complexin seems to (i) clamp the SNARE complex to prevent premature fusion, and (ii) to potentiate the Ca2+-sensor activity of synaptotagmin on the SNARE complex, as synaptotagmin–Ca2+ is insufficient for triggering fusion in the absence of complexin. Do these complexin activities fully account for its apparent positive role in fast, Ca2+-dependent neurotransmitter release? Possibly, but it might also have a direct role in forming a hemifused intermediate state (Schaub et al, 2006), or a ‘superprimed' metastable intermediate (Tang et al, 2006), although the mechanistic details of both models are still unclear.

Does synaptotagmin have an additional role in directly promoting the membrane fusion reaction? It is possible that the only role of synaptotagmin is to release complexin, allowing the SNAREs to fuse the membranes. However, synaptotagmin has been proposed to have a more direct role in stimulating membrane fusion, through its ability to bind to lipids and promote positive membrane curvature, which would help reduce the energy barrier to SNARE-mediated membrane fusion (Arac et al, 2006; Martens et al, 2007). This idea might explain the requirement for the transmembrane domain of synaptotagmin and its restriction to the synaptic vesicle membrane. Both features might only be used to help tether and align the C2A and C2B domains into the correct orientation for SNARE complex interactions, but it is likely that synaptotagmin does more than just release the complexin clamp to trigger the SNAREs for fusion.

Concluding remarks

These recent results represent significant new insights into the mechanism by which synaptotagmin and complexin collaborate to produce fast, synchronous, Ca2+-stimulated neurotransmitter release. Future combinations of structural, biophysical and genetic experiments will no doubt further refine the molecular details of these mechanisms. Clearly, however, there is much more to be understood—even with the addition of complexin and synaptotagmin–Ca2+, in vitro fusion assays are at least 2–3 orders of magnitude slower than physiological fusion. Additional studies will be necessary to incorporate other regulatory factors, such as Sec1/Munc18 (Scott et al, 2004; Dulubova et al, 2007; Shen et al, 2007), Munc13, tomosyn, synaptophysin, tethering complexes and specific phospholipids, as well as post-translational modifications (such as phosphorylation), which might all have significant roles in regulation and/or the membrane fusion step itself.

Chavela M. Carr

Mary Munson

Acknowledgments

We regret that owing to space considerations, many important papers could not be directly cited in this work. We thank M. Yoshihara, D. Bolon, J. Saporita and W. Kobertz for critical reading of this manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Health to C.M.C. (GM066291) and to M.M. (GM068803).

References

- Arac D, Chen X, Khant HA, Ubach J, Ludtke SJ, Kikkawa M, Johnson AE, Chiu W, Sudhof TC, Rizo J (2006) Close membrane–membrane proximity induced by Ca2+-dependent multivalent binding of synaptotagmin-1 to phospholipids. Nat Struct Mol Biol 13: 209–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai J, Chapman ER (2004) The C2 domains of synaptotagmin—partners in exocytosis. Trends Biochem Sci 29: 143–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifacino JS, Glick BS (2004) The mechanisms of vesicle budding and fusion. Cell 116: 153–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen ME, Weninger K, Ernst J, Chu S, Brunger AT (2005) Single-molecule studies of synaptotagmin and complexin binding to the SNARE complex. Biophys J 89: 690–702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracher A, Kadlec J, Betz H, Weissenhorn W (2002) X-ray structure of a neuronal complexin–SNARE complex from squid. J Biol Chem 277: 26517–26523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunger AT (2005) Structure and function of SNARE and SNARE-interacting proteins. Q Rev Biophys 38: 1–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman ER (2002) Synaptotagmin: a Ca2+ sensor that triggers exocytosis? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 3: 498–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Tomchick DR, Kovrigin E, Arac D, Machius M, Sudhof TC, Rizo J (2002) Three-dimensional structure of the complexin/SNARE complex. Neuron 33: 397–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai H, Shen N, Arac D, Rizo J (2007) A quaternary SNARE–synaptotagmin–Ca2+–phospholipid complex in neurotransmitter release. J Mol Biol 367: 848–863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulubova I, Khvotchev M, Liu S, Huryeva I, Sudhof TC, Rizo J (2007) Munc18-1 binds directly to the neuronal SNARE complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 2697–2702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez I, Arac D, Ubach J, Gerber SH, Shin O, Gao Y, Anderson RG, Sudhof TC, Rizo J (2001) Three-dimensional structure of the synaptotagmin 1 C2B-domain: synaptotagmin 1 as a phospholipid binding machine. Neuron 32: 1057–1069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Chacon R, Konigstorfer A, Gerber SH, Garcia J, Matos MF, Stevens CF, Brose N, Rizo J, Rosenmund C, Sudhof TC (2001) Synaptotagmin I functions as a calcium regulator of release probability. Nature 410: 41–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geppert M, Goda Y, Hammer RE, Li C, Rosahl TW, Stevens CF, Sudhof TC (1994) Synaptotagmin I: a major Ca2+ sensor for transmitter release at a central synapse. Cell 79: 717–727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraudo CG, Eng WS, Melia TJ, Rothman JE (2006) A clamping mechanism involved in SNARE-dependent exocytosis. Science 313: 676–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu C, Ahmed M, Melia TJ, Sollner TH, Mayer T, Rothman JE (2003) Fusion of cells by flipped SNAREs. Science 300: 1745–1749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahn R, Scheller RH (2006) SNAREs—engines for membrane fusion. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7: 631–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Augustine G, Weninger K (2007) Kinetics of complexin binding to the SNARE complex: correcting single molecule FRET measurements for hidden events. Biophys J [doi:10.1529/biophysj.106.101220] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens S, Kozlov MM, McMahon HT (2007) How synaptotagmin promotes membrane fusion. Science 316: 1205–1208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marz KE, Hanson PI (2002) Sealed with a twist: complexin and the synaptic SNARE complex. Trends Neurosci 25: 381–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono S, Baux G, Sekiguchi M, Fossier P, Morel NF, Nihonmatsu I, Hirata K, Awaji T, Takahashi S, Takahashi M (1998) Regulatory roles of complexins in neurotransmitter release from mature presynaptic nerve terminals. Eur J Neurosci 10: 2143–2152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pabst S, Hazzard JW, Antonin W, Sudhof TC, Jahn R, Rizo J, Fasshauer D (2000) Selective interaction of complexin with the neuronal SNARE complex. Determination of the binding regions. J Biol Chem 275: 19808–19818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reim K, Mansour M, Varoqueaux F, McMahon HT, Sudhof TC, Brose N, Rosenmund C (2001) Complexins regulate a late step in Ca2+-dependent neurotransmitter release. Cell 104: 71–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizo J, Chen X, Arac D (2006) Unraveling the mechanisms of synaptotagmin and SNARE function in neurotransmitter release. Trends Cell Biol 16: 339–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roggero CM, De Blas GA, Dai H, Tomes CN, Rizo J, Mayorga LS (2007) Complexin/synaptotagmin interplay controls acrosomal exocytosis. J Biol Chem [doi:10.1074/jbc.M700854200] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaub JR, Lu X, Doneske B, Shin YK, McNew JA (2006) Hemifusion arrest by complexin is relieved by Ca2+-synaptotagmin I. Nat Struct Mol Biol 13: 748–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott BL, Van Komen JS, Irshad H, Liu S, Wilson KA, McNew JA (2004) Sec1p directly stimulates SNARE-mediated membrane fusion in vitro. J Cell Biol 167: 75–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao X, Fernandez I, Sudhof TC, Rizo J (1998) Solution structures of the Ca2+-free and Ca2+-bound C2A domain of synaptotagmin I: does Ca2+ induce a conformational change? Biochemistry 37: 16106–16115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J, Tareste DC, Paumet F, Rothman JE, Melia TJ (2007) Selective activation of cognate SNAREpins by Sec1/Munc18 proteins. Cell 128: 183–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sollner TH (2003) Regulated exocytosis and SNARE function. Mol Membr Biol 20: 209–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudhof TC (2004) The synaptic vesicle cycle. Annu Rev Neurosci 27: 509–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton RB, Fasshauer D, Jahn R, Brunger AT (1998) Crystal structure of a SNARE complex involved in synaptic exocytosis at 2.4 Å resolution. Nature 395: 347–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton RB, Ernst JA, Brunger AT (1999) Crystal structure of the cytosolic C2A-C2B domains of synaptotagmin III. Implications for Ca+2-independent snare complex interaction. J Cell Biol 147: 589–598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takamori S et al. (2006) Molecular anatomy of a trafficking organelle. Cell 127: 831–846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J, Maximov A, Shin OH, Dai H, Rizo J, Sudhof TC (2006) A complexin/synaptotagmin 1 switch controls fast synaptic vesicle exocytosis. Cell 126: 1175–1187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokumaru H, Umayahara K, Pellegrini LL, Ishizuka T, Saisu H, Betz H, Augustine GJ, Abe T (2001) SNARE complex oligomerization by synaphin/complexin is essential for synaptic vesicle exocytosis. Cell 104: 421–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters MG, Hughson FM (2000) Membrane tethering and fusion in the secretory and endocytic pathways. Traffic 1: 588–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber T, Zemelman BV, McNew JA, Westermann B, Gmachl M, Parlati F, Sollner TH, Rothman JE (1998) SNAREpins: minimal machinery for membrane fusion. Cell 92: 759–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whyte JR, Munro S (2002) Vesicle tethering complexes in membrane traffic. J Cell Sci 115: 2627–2637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue M, Reim K, Chen X, Chao HT, Deng H, Rizo J, Brose N, Rosenmund C (2007) Distinct domains of complexin I differentially regulate neurotransmitter release. Nat Struct Mol Biol (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon TY, Okumus B, Zhang F, Shin YK, Ha T (2006) Multiple intermediates in SNARE-induced membrane fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 19731–19736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihara M, Littleton JT (2002) Synaptotagmin I functions as a calcium sensor to synchronize neurotransmitter release. Neuron 36: 897–908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihara M, Adolfsen B, Littleton JT (2003) Is synaptotagmin the calcium sensor? Curr Opin Neurobiol 13: 315–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]