Reporter gene assays facilitate analysis of transcriptional activity [1]. In such experiments, the initial characterization of the transcriptional activity of the gene product of interest is analyzed through its ability to bind to its cognate promoter sequence and either activate or repress a reporter gene’s activity. This is achieved by cloning the target promoter sequence upstream of a reporter gene. This construct is referred to as the experimental reporter. Measurement of the activity of the experimental reporter (i.e., assaying reporter gene product levels) in the presence of the gene of interest (effector gene) reflects effector gene product activity. Variations in the transcriptional activity of the effector gene are then reflected in changes in the levels of expression of the reporter gene. To quantitate the reporter gene activity accurately, the transfection efficiency of all plasmids must be taken into account. One of the most common methods of determining transfection efficiency is to introduce and measure the activity of a second reporter gene (control reporter) under the control of a constitutive promoter within the same experimental setting.

Reporter genes that have been used to determine transfection efficiency include chloramphenicol acetyl transferase (CAT),1 β -galactosidase, luciferase, and green fluorescent protein (GFP) [2–4]. The luciferase reporter gene system is widely used due to its detection sensitivity and the ease of quantification when compared with the other available systems [5]. The luciferase gene from the sea pansy Renilla reniformis under the control of either simian virus 40 (SV40), cytomegalovirus (CMV), or thymidine kinase (TK) promoter is routinely used for this purpose. The Renilla control reporter, when cotransfected into cells with the experimental reporter and the effector construct, allows the evaluation of experimental variation such as transfection efficiency and cell viability. In general, for these assay systems, luciferase from the firefly Photinus pyralis is used as the experimental reporter. The advantage of this dual luciferase system is that because the substrate requirements of the two luciferases are unique, their respective expression levels can be estimated sequentially from within the same sample.

Despite these advantages, there have been reports of aberrant activation or repression of control reporter genes by the effector constructs [6–8]. Ideally, expression of the control reporter should depend primarily on transfection efficiency. However, a number of factors, such as culture conditions and the activity of the effector gene along with the promoters used, can alter the levels of control reporter expression. Such spurious expression of the control reporter can cause a bias during the normalization of data.

In this article, we report the use of enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) as an alternative control reporter to Renilla luciferase. We show that the use of EGFP as a control reporter is robust and can produce consistent results in experimental settings where dysregulation of Renilla luciferase is observed. Importantly, EGFP activity can be measured in vivo; thus, one can determine the transfection efficiency at any time point rather than measuring it at the end of the experiment.

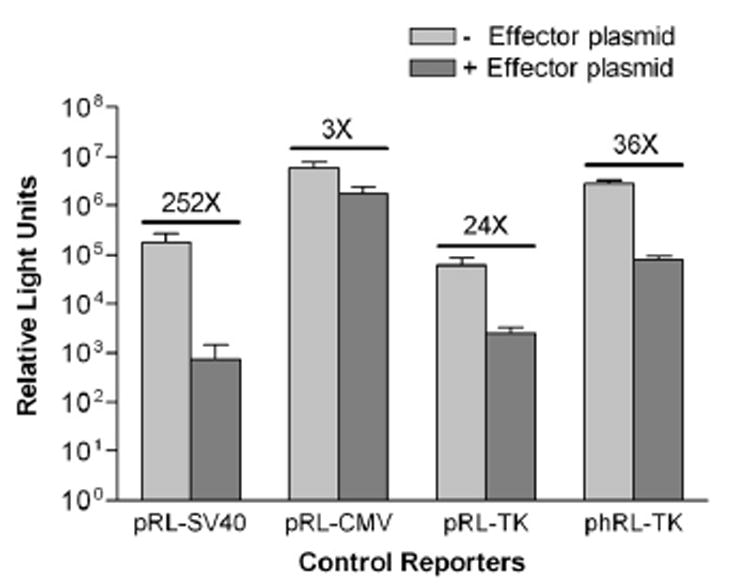

In our studies directed at deciphering the role of dysregulated transcription factors in breast cancer biogenesis, we routinely use cotransfection assays in tissue culture cells to determine effects of transcription factors on downstream target genes. A rather simple and apparently straightforward method of studying the transcriptional regulation of these genes is the Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The assay is performed on lysates prepared from tissue culture cells that have been cotransfected with experimental reporter, effector vector, and control reporter vector. The Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay provides Renilla luciferase as the control reporter. The firefly luciferase activity in cell lysates is measured first and reflects effector gene activity. Renilla luciferase activity is measured subsequently and indicates transfection efficiency. To normalize the levels of the experimental reporter activity, firefly luciferase values are divided by Renilla luciferase values for each set of readings. Following data normalization, we found that experimental reporter activity was upregulated by the effector construct. However, a thorough examination of the results revealed that the effector construct had downregulated expression of Renilla luciferase 252-fold (Fig. 1). This difference in data interpretation could have a significant impact on subsequent experiments. Before pursuing the research further or changing the control reporter gene, we considered the possibility that the repression of Renilla might be alleviated by using a different constitutive promoter. Surprisingly, both pRL–CMV and pRL–TK control reporters were downregulated by the effector construct by an average of 3- and 24-fold, respectively (Fig. 1). Although the repression observed using the CMV or TK promoter was less than that using the SV40 promoter, the values obtained were sufficient to cause a significant bias in the normalized results. The SV40, CMV, and TK promoters have different numbers of putative transcription factor binding sites. This could explain, in part, the variation in the promoter activity in the presence of the effector gene product. In addition, the Renilla gene itself has more than 200 miscellaneous transcription factor binding sites [9]. Apparently because of similar difficulties faced by many researchers with the first generation of Renilla vectors, a second generation of control reporter vectors, referred to as phRL, has been constructed (Promega). The new Renilla coding sequence of phRL has been engineered to be devoid of numerous transcription factor binding sites present in the native Renilla coding sequence. In addition, phRL has been designed for optimal translation in mammalian cells. Both of these modifications are meant to reduce the frequency of anomalous reporter activity. In contrast, there have been no reports of an engineering of promoters in a manner that would limit or abolish spurious regulation of reporter control gene expression. As seen in Fig. 1, use of phRL–TK as the control reporter produced a 47-fold increase in the absolute values of the reporter levels but without any significant change in the fold repression by the effector construct (mean = 36×).

Fig. 1.

Log plot showing that the Renilla control reporter is suppressed in the presence of effector construct. MCF-7 breast cancer cells were transiently cotransfected with the indicated control reporters (Promega), without or with effector construct, using TransIT–LT1 reagent (Mirus Bio, Madison, WI, USA) and following the manufacturer’s instructions. The modified Renilla gene of the phRL–TK vector (Promega) was also tested. Luminosities, recorded as relative light units (RLU), were obtained using a Sirius luminometer (Berthold Detection Systems, Oak Ridge, TN, USA) after analyzing the transfected cells by the Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay (Promega). Measurements are 48 h posttransfection. The values shown above the bar graphs are the fold drops in RLU of the controls in the presence of the effector construct. Error bars show standard deviations. Histograms display means of 10 replicates of each experiment. Graphs were plotted using Prism 3 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA), with error bars showing standard deviations.

Such results led us to consider alternative control reporters, and we considered EGFP to be an excellent choice. We reasoned that an EGFP control reporter could perhaps not only overcome the repression observed with the Renilla control reporter but might also provide us with the advantage of obtaining in vivo measurements of control reporter activity longitudinally rather than at a single time point. Thus, an EGFP control reporter would provide the possibility of measuring transfection efficiency at multiple time points. Since the reason for using control reporter genes is to evaluate transfection efficiency, we thought that estimating the levels of EGFP at different time points would be ideal.

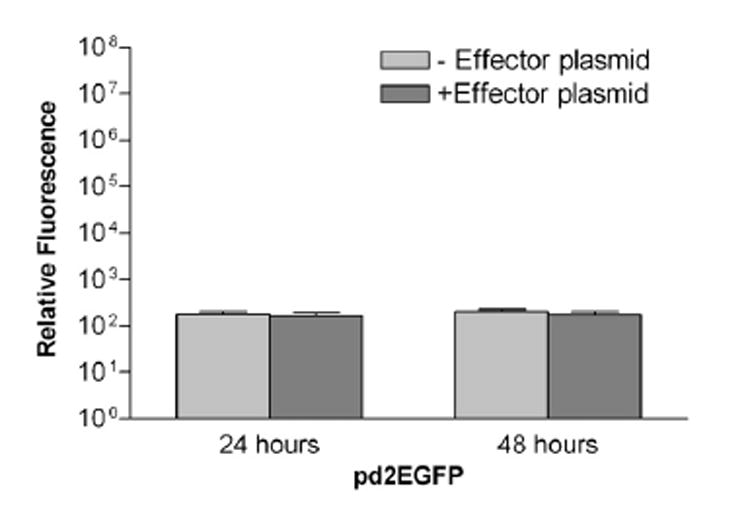

Although GFP has been used as a reporter in a variety of experimental conditions [10,11], our method has the distinct advantage that it can handle a large number of samples in a very short time period and is not limited by cell numbers. Using EGFP as a control reporter, we found that the effector gene suppressed EGFP levels by a nonsignificant 8% (Fig. 2) within 24 h and a maximum of 16% within 48 h. This is in comparison with the 3- to 252-fold decrease that was observed using Renilla as the control reporter gene. Also, the repression of the reporter gene by the transcription factor was not dependent on the amount of the reporter plasmid used in this study (200–500 ng of pd2EGFP).

Fig. 2.

Log plot showing that EGFP control reporter is not significantly suppressed in the presence of effector construct. MCF-7 cells were transfected as described in Fig. 1 using pd2EGFP vector (BD Biosciences, Palo Alto, CA, USA) as the control reporter. For EGFP fluorescence measurements, cells in 24-well plates were assayed in a Wallac 1420 VICTOR3 plate reader (Perkin-Elmer, Boston, MA, USA). Fluorescence measurements of 5 s per well were obtained at 24 and 48 h. Relative fluorescence levels show less suppression due to the effector construct at 24 h than at 48 h. Error bars show standard deviations.

In summary, we suggest that the use of EGFP as a control reporter is valid and generates results that are unambiguous to interpret. Use of EGFP as a control reporter could be a superior option to using Renilla, especially in systems where suppression of the Renilla reporter caused by expression of the effector gene is observed.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a National Institutes of Health grant (1RO1CA097226) to Venu Raman. We thank Balaji Krishnamachari (Institute of Cell Engineering, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine) for the EGFP measurements and Steven R. Brant (Gastroenterology Division, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine) for the phRL–TK vector.

Abbreviations used

- CAT

chloramphenicol acetyl transferase

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- SV40

simian virus 40

- CMV

cytomegalovirus

- TK

thymidine kinase

- EGFP

enhanced green fluorescent protein

References

- 1.Rosenthal N. Identification of regulatory elements of cloned genes with functional assays. Methods Enzymol. 1987;152:704–720. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)52075-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wood KV. Marker proteins for gene expression. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1995;6:50–58. doi: 10.1016/0958-1669(95)80009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schenborn E, Groskreutz D. Reporter gene vectors and assays. Mol Biotechnol. 1999;13:29–44. doi: 10.1385/MB:13:1:29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chalfie M, Tu Y, Euskirchen G, Ward WW, Prasher DC. Green fluorescent protein as a marker for gene expression. Science. 1994;263:802–805. doi: 10.1126/science.8303295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Wet JR, Wood KV, DeLuca M, Helinski DR, Subramani S. Firefly luciferase gene: structure and expression in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:725–737. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.2.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farr A, Roman A. A pitfall of using a second plasmid to determine transfection efficiency. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:920. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.4.920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ibrahim NM, Marinovic AC, Price SR, Young LG, Frohlich O. Pitfall of an internal control plasmid: response of Renilla luciferase (pRL–TK) plasmid to dihydrotestosterone and dexamethasone. BioTechniques. 2000;29:782–784. doi: 10.2144/00294st04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mulholland DJ, Cox M, Read J, Rennie P, Nelson C. Androgen responsiveness of Renilla luciferase reporter vectors is promoter, transgene, and cell line dependent. Prostate. 2004;59:115–119. doi: 10.1002/pros.20059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhuang Y, Butler B, Hawkins E, Paguio A, Orr L, Wood M, Wood KV. New synthetic Renilla gene and assay system increase expression, reliability, and sensitivity. Promega Notes. 2001;79:6–11. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsien RY. The green fluorescent protein. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:509–544. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sims RJ, III, Liss AS, Gottlieb PD. Normalization of luciferase reporter assays under conditions that alter internal controls. BioTechniques. 2003;34:938–940. doi: 10.2144/03345bm07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]