Abstract

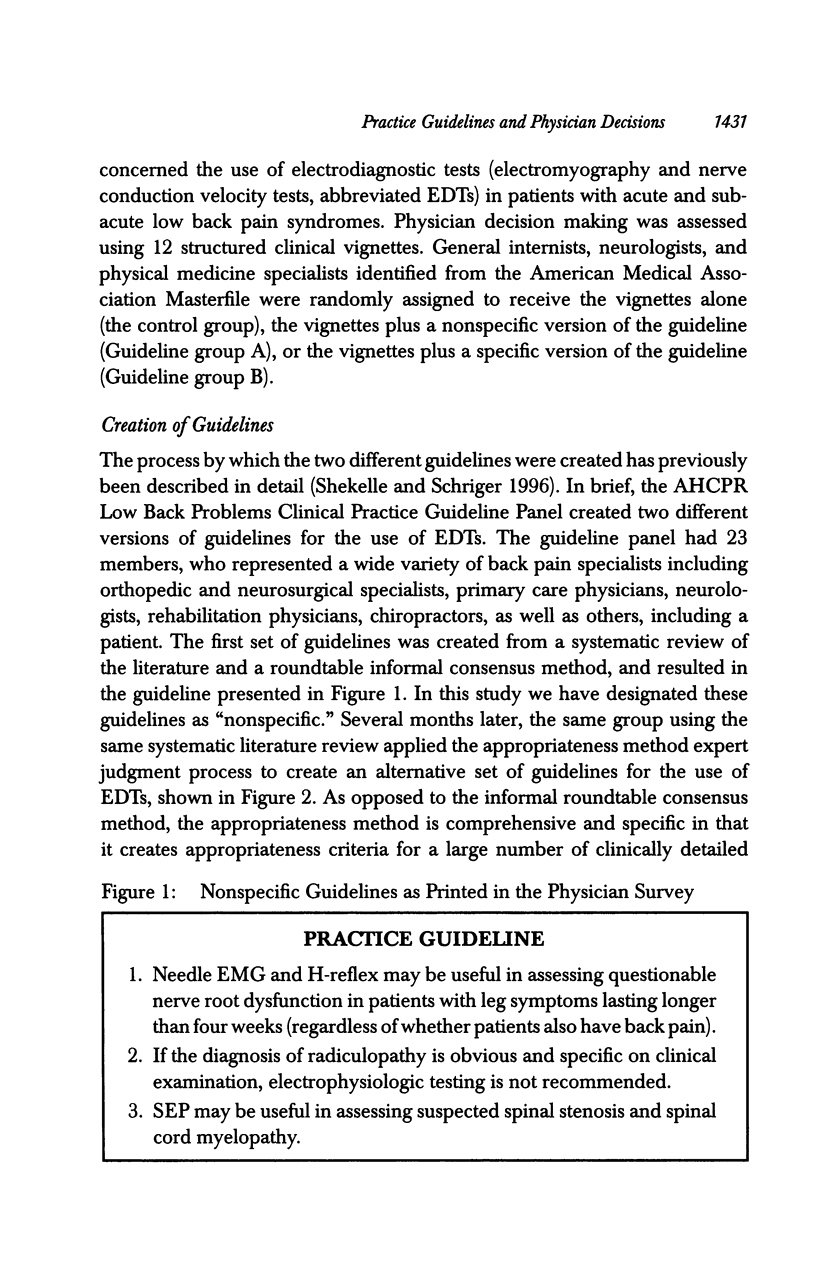

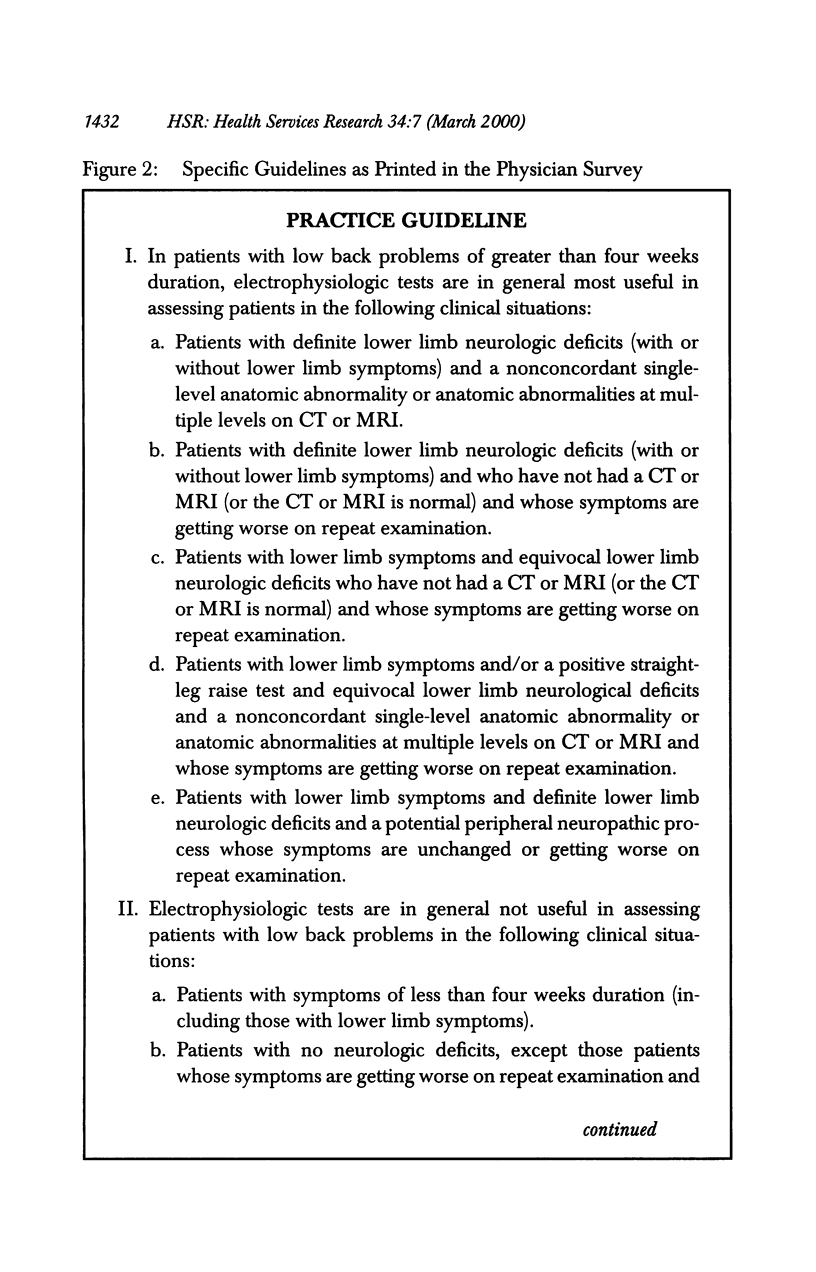

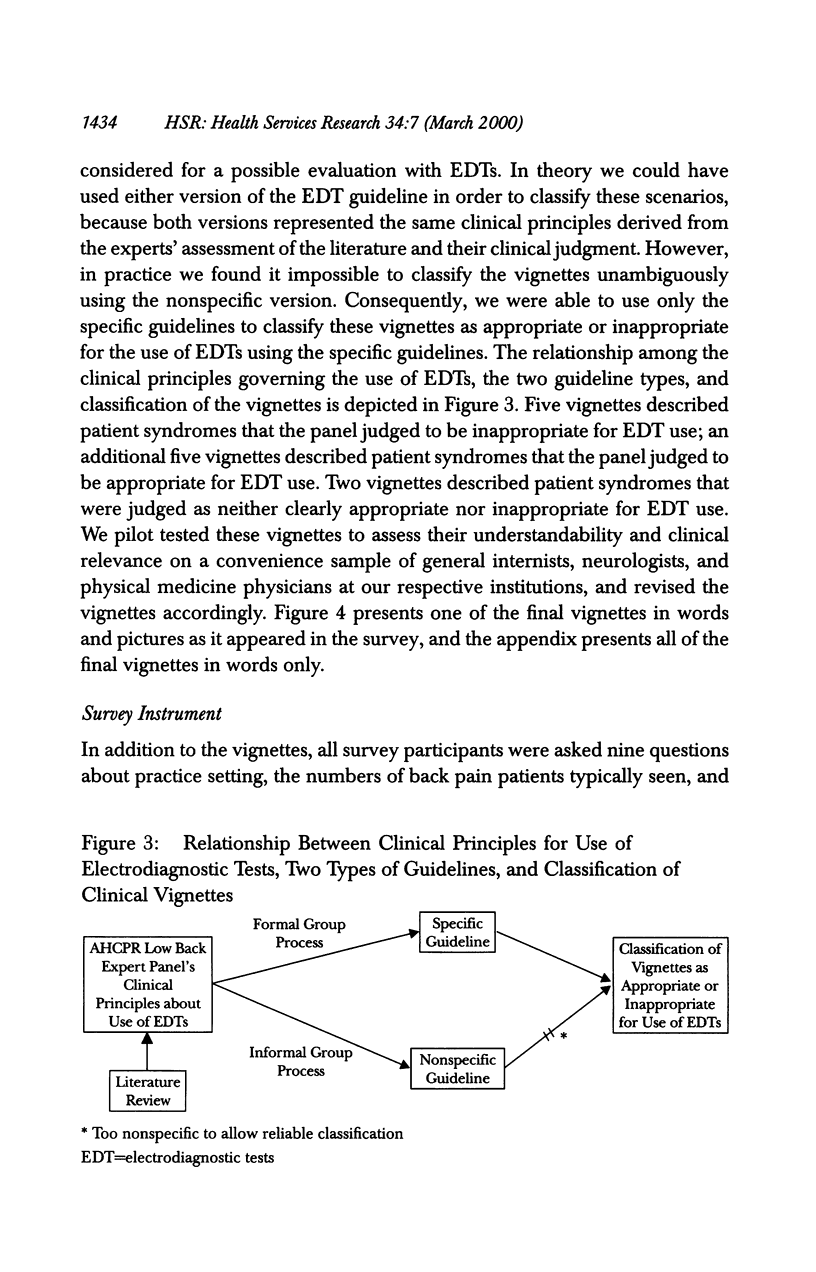

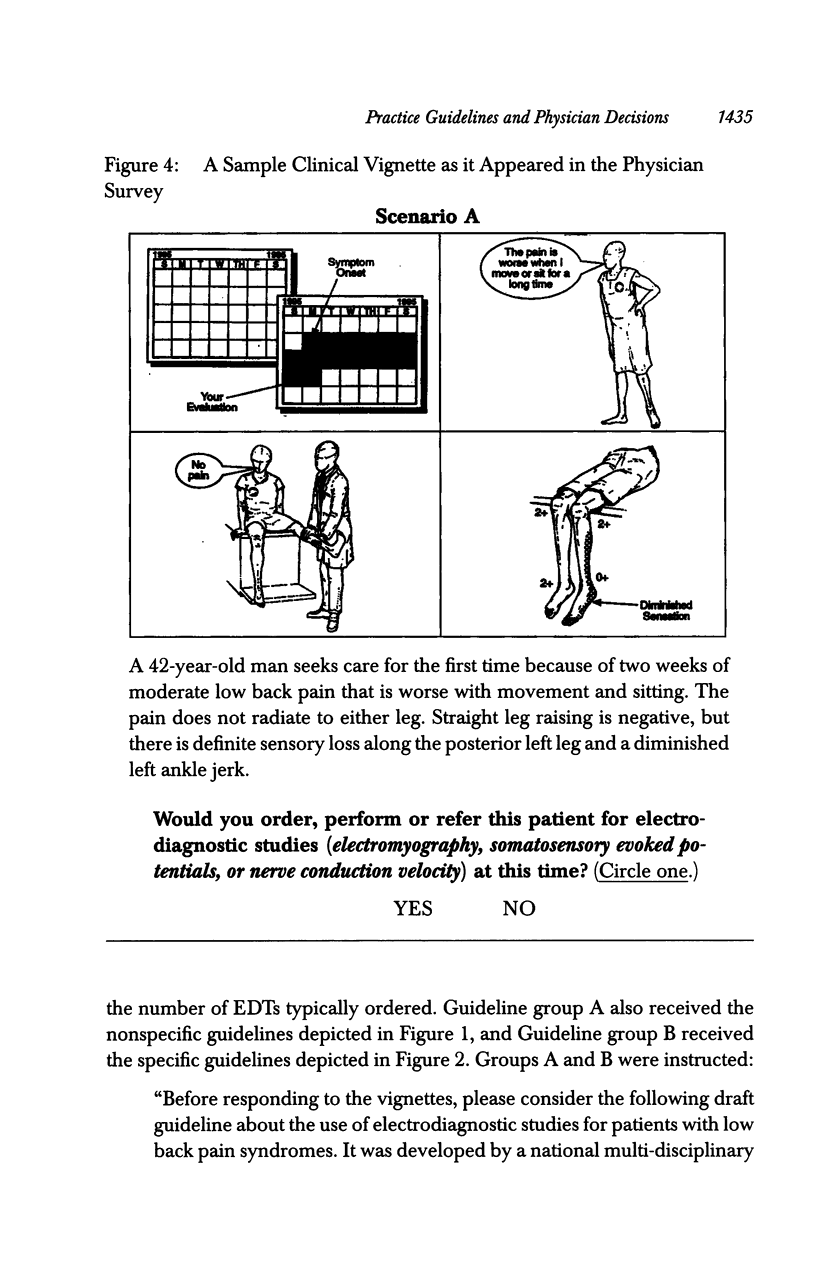

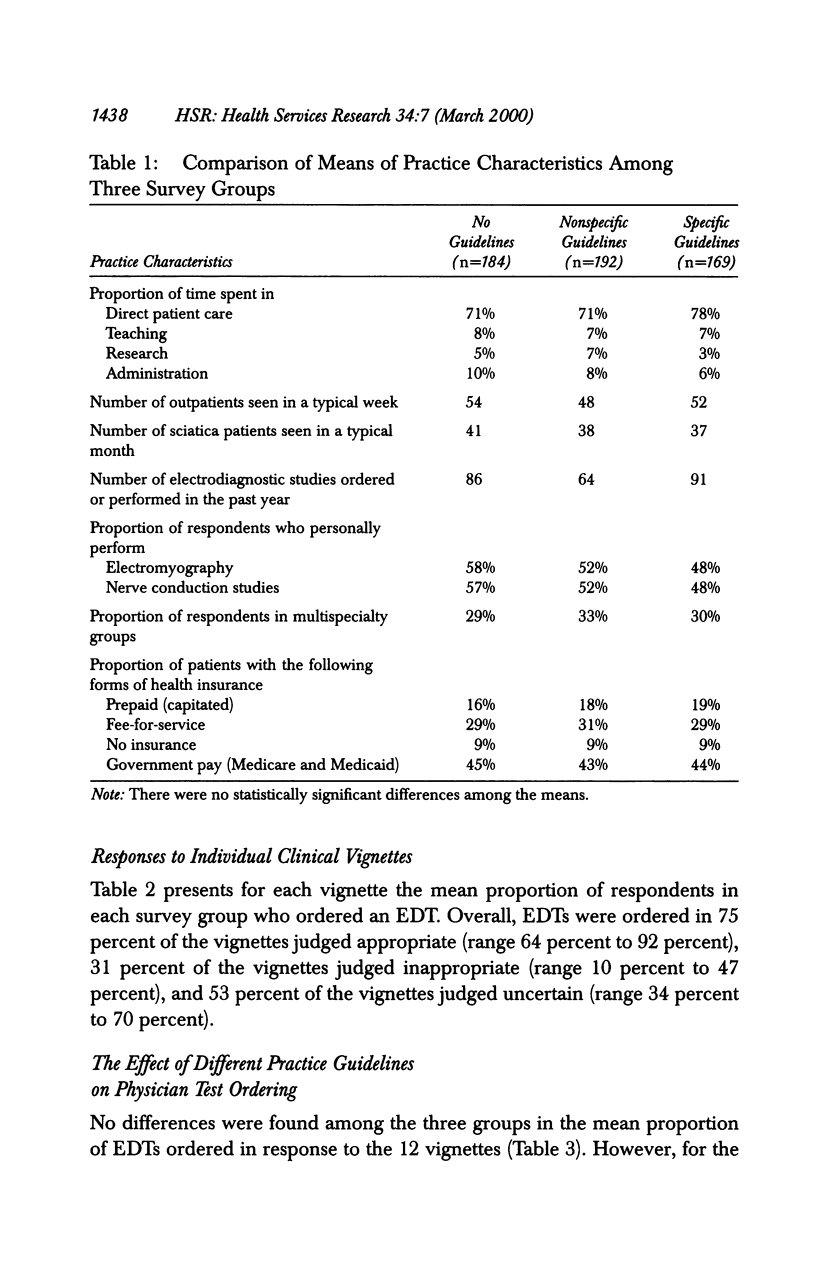

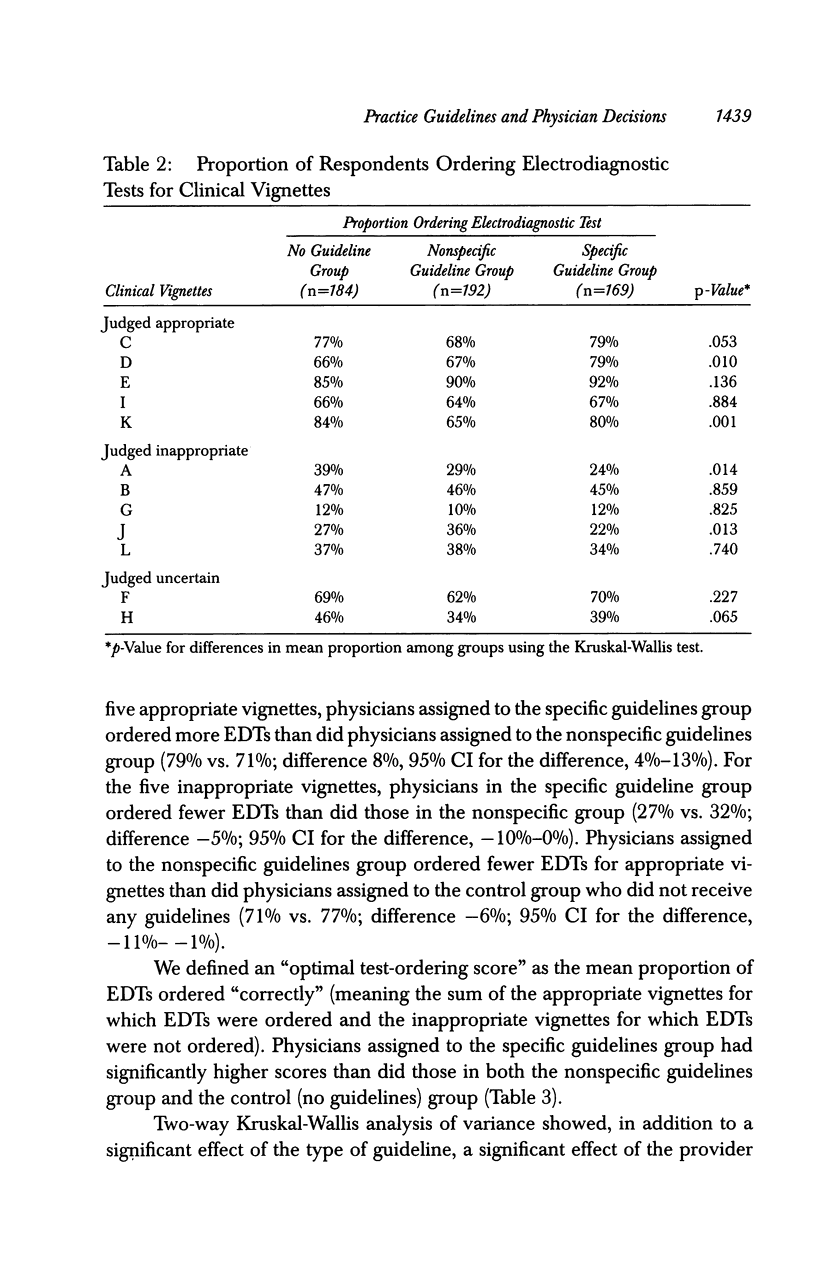

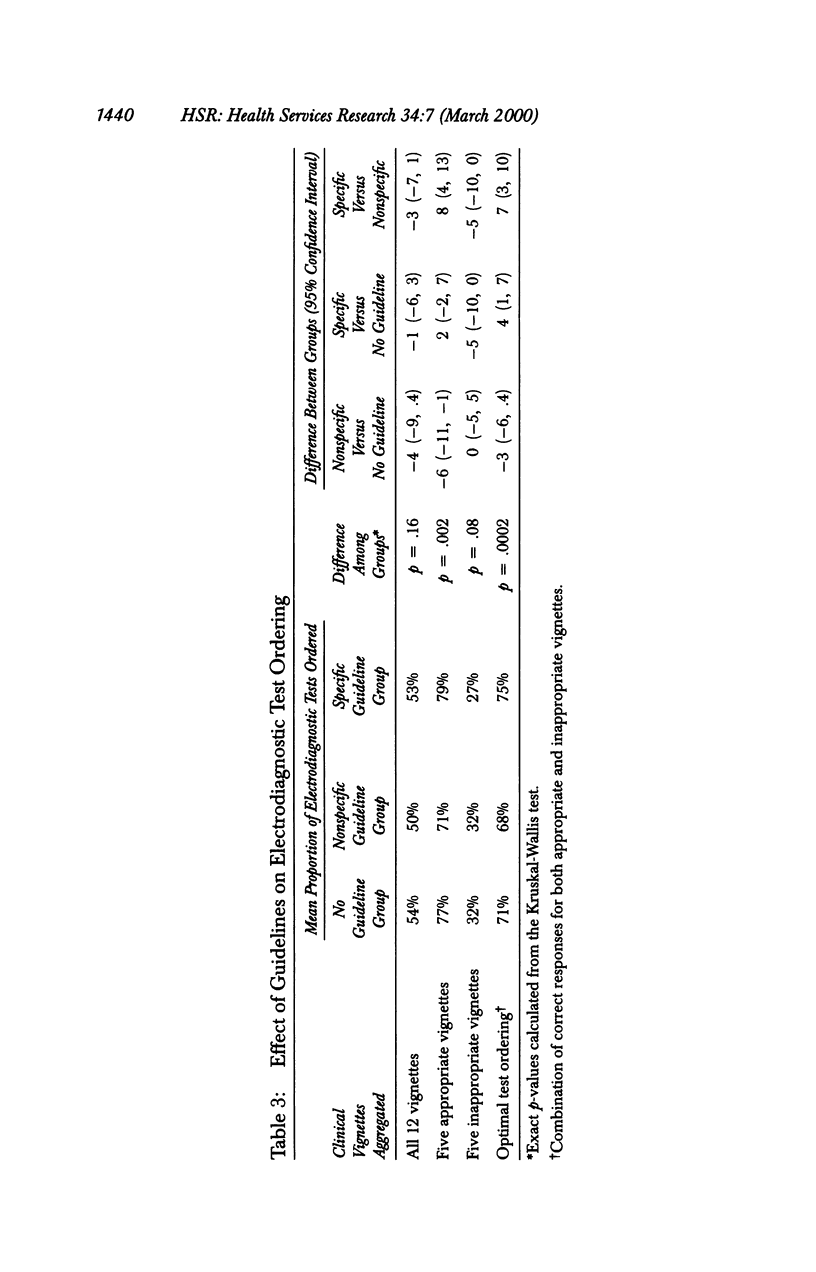

OBJECTIVE: To test the ability of two different clinical practice guideline formats to influence physician ordering of electrodiagnostic tests in low back pain. DATA SOURCES/STUDY DESIGN: Randomized controlled trial of the effect of practice guidelines on self-reported physician test ordering behavior in response to a series of 12 clinical vignettes. Data came from a national random sample of 900 U.S. neurologists, physical medicine physicians, and general internists. INTERVENTION: Two different versions of a practice guideline for the use of electrodiagnostic tests (EDT) were developed by the U.S. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research Low Back Problems Panel. The two guidelines were similar in content but varied in the specificity of their recommendations. DATA COLLECTION: The proportion of clinical vignettes for which EDTs were ordered for appropriate and inappropriate clinical indications in each of three physician groups were randomly assigned to receive vignettes alone, vignettes plus the nonspecific version of the guideline, or vignettes plus the specific version of the guideline. PRINCIPAL FINDINGS: The response rate to the survey was 71 percent. The proportion of appropriate vignettes for which EDTs were ordered averaged 77 percent for the no guideline group, 71 percent for the nonspecific guideline group, and 79 percent for the specific guideline group (p = .002). The corresponding values for the number of EDTs ordered for inappropriate vignettes were 32 percent, 32 percent, and 26 percent, respectively (p = .08). Pairwise comparisons showed that physicians receiving the nonspecific guidelines ordered fewer EDTs for appropriate clinical vignettes than did physicians receiving no guidelines (p = .02). Furthermore, compared to physicians receiving nonspecific guidelines, physicians receiving specific guidelines ordered significantly more EDTs for appropriate vignettes (p = .0007) and significantly fewer EDTs for inappropriate vignettes (p = .04). CONCLUSIONS: The clarity and clinical applicability of a guideline may be important attributes that contribute to the effects of practice guidelines.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Audet A. M., Greenfield S., Field M. Medical practice guidelines: current activities and future directions. Ann Intern Med. 1990 Nov 1;113(9):709–714. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-9-709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braspenning J., Sergeant J. General practitioners' decision making for mental health problems: outcomes and ecological validity. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994 Dec;47(12):1365–1372. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook R. H., Chassin M. R., Fink A., Solomon D. H., Kosecoff J., Park R. E. A method for the detailed assessment of the appropriateness of medical technologies. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1986;2(1):53–63. doi: 10.1017/s0266462300002774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey T. S., Garrett J. Patterns of ordering diagnostic tests for patients with acute low back pain. The North Carolina Back Pain Project. Ann Intern Med. 1996 Nov 15;125(10):807–814. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-10-199611150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherkin D. C., Deyo R. A., Wheeler K., Ciol M. A. Physician variation in diagnostic testing for low back pain. Who you see is what you get. Arthritis Rheum. 1994 Jan;37(1):15–22. doi: 10.1002/art.1780370104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles M., Clapp Z., Grimshaw J., Adams P. C., Higgins B., Purves I., Russell I. Developing valid guidelines: methodological and procedural issues from the North of England Evidence Based Guideline Development Project. Qual Health Care. 1996 Mar;5(1):44–50. doi: 10.1136/qshc.5.1.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy D. M. Clinical decision making: from theory to practice. Practice policies--guidelines for methods. JAMA. 1990 Apr 4;263(13):1839–1841. doi: 10.1001/jama.263.13.1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimshaw J., Eccles M., Russell I. Developing clinically valid practice guidelines. J Eval Clin Pract. 1995 Sep;1(1):37–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.1995.tb00006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimshaw J., Russell I. Achieving health gain through clinical guidelines. I: Developing scientifically valid guidelines. Qual Health Care. 1993 Dec;2(4):243–248. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2.4.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grol R., Dalhuijsen J., Thomas S., Veld C., Rutten G., Mokkink H. Attributes of clinical guidelines that influence use of guidelines in general practice: observational study. BMJ. 1998 Sep 26;317(7162):858–861. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7162.858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward R. S., Wilson M. C., Tunis S. R., Bass E. B., Guyatt G. Users' guides to the medical literature. VIII. How to use clinical practice guidelines. A. Are the recommendations valid? The Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1995 Aug 16;274(7):570–574. doi: 10.1001/jama.274.7.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones T. V., Gerrity M. S., Earp J. Written case simulations: do they predict physicians' behavior? J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43(8):805–815. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90241-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosecoff J., Kanouse D. E., Rogers W. H., McCloskey L., Winslow C. M., Brook R. H. Effects of the National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Program on physician practice. JAMA. 1987 Nov 20;258(19):2708–2713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald C. J., Overhage J. M. Guidelines you can follow and can trust. An ideal and an example. JAMA. 1994 Mar 16;271(11):872–873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shekelle P. G., Schriger D. L. Evaluating the use of the appropriateness method in the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research Clinical Practice Guideline Development process. Health Serv Res. 1996 Oct;31(4):453–468. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wennberg D. E., Dickens J. D., Jr, Biener L., Fowler F. J., Jr, Soule D. N., Keller R. B. Do physicians do what they say? The inclination to test and its association with coronary angiography rates. J Gen Intern Med. 1997 Mar;12(3):172–176. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-5025-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf S. H. Practice guidelines, a new reality in medicine. II. Methods of developing guidelines. Arch Intern Med. 1992 May;152(5):946–952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]