Abstract

Purpose

The role of complement in ocular autoimmunity was explored in a experimental autoimmune anterior uveitis (EAAU) animal model.

Methods

EAAU was induced in Lewis rats by immunization with bovine melanin-associated antigen. Complement activation in the eye was monitored by Western blot for iC3b. The importance of complement to the development of EAAU was studied by comparing the course of intraocular inflammation in normal Lewis rats (complement-sufficient) with cobra venom factor–treated rats (complement-depleted). Eyes were harvested from both complement-sufficient and complement-depleted rats for mRNA and protein analysis for IFN-γ, IL-10, and interferon-inducible protein (IP)-10. Intracellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1 and leukocyte–endothelial cell adhesion molecule (LECAM)-1 were detected by immunofluorescent staining. OX-42 was used to investigate the importance of iC3b and CR3 interaction in EAAU.

Results

There was a correlation between ocular complement activation and disease progression in EAAU. The incidence, duration, and severity of disease were dramatically reduced after active immunization in complement-depleted rats. Complement depletion also completely suppressed adoptive transfer EAAU. The presence of complement was critical for local production of cytokines (IFN-γ and IL-10), chemokines (IP-10), and adhesion molecules (ICAM-1 and LECAM-1) during EAAU. Furthermore, intraocular complement activation, specifically iC3b production and engagement of complement receptor 3 (CR3), had a significant impact on disease activity in EAAU.

Conclusions

The study provided the novel finding that complement activation plays a central role in the pathogenesis of ocular autoimmunity and may serve as a potential target for therapeutic intervention.

Complement is a major component of innate immunity.1 In recent years, it has become increasingly evident that complement is also involved in the antigen-specific immune responses with an identified role in antigen processing and presentation, T-cell proliferation and differentiation, B-cell activation,2–3 and systemic tolerance induced by the introduction of antigen into an immune-privileged site such as the anterior chamber of the eye.4 Inappropriate activation of complement has been implicated in various diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease, ischemia–reperfusion injury, Huntington’s and prion disease, and multiple sclerosis (MS).5–9 However, the role of complement in ocular autoimmune disease is not well understood.

Experimental autoimmune anterior uveitis (EAAU) is an organ-specific autoimmune disease of the eye that serves as an animal model of idiopathic human anterior uveitis.10–14 We have previously shown that in this model, severe inflammation occurs in the anterior segment of the eye of Lewis rats after the footpad injection of melanin-associated antigen (MAA).11–14 Antigen-specific CD4+ T cells can adoptively transfer disease into naïve syngeneic recipients and are the predominant inflammatory cells within the uvea.12–14 The purpose of the present study was to investigate the role of complement in the pathogenesis of EAAU.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male Lewis rats (5–6 weeks old) were obtained from Harlan Sprague-Dawley (Indianapolis, IN). All animals were treated in accordance with the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research.

Antibodies and Reagents

The IgG fraction of goat antiserum to rat C3 was from ICN Biochemicals Inc. (Aurora, OH) and purified IgG fraction of rabbit anti-rat interferon-inducible protein (IP)-10 was from Torrey Pines Biolabs, Inc. (Houston, TX). Purified rabbit IgG (polyclonal) immunoglobulin isotype standard, FITC-labeled mouse anti-rat CD54 (ICAM-1, IgG1κ), FITC-labeled hamster anti-rat CD62L (L-selectin, leukocyte–endothelial cell adhesion molecule [LECAM-1], IgG2λ) monoclonal antibodies, and respective isotype controls were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA). Mouse anti-rat CD11b (MRC OX-42, IgG2a), FITC-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG2a (rat adsorbed) and isotype control antibodies were from Serotec (Raleigh, NC). Purified cobra venom factor (CVF) was from Quidel Corp. (San Diego, CA). Bovine serum albumin (BSA) and ITS+1 liquid medium supplement were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Induction and Evaluation of EAAU

Lewis rats were immunized with 100 μL of stable emulsion containing 75μg MAA emulsified (1:1) in complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA; Difco Laboratories, Inc., Detroit, MI) using a single-dose induction protocol in the hind footpad, as previously described by us.11–14 Purified pertussis toxin (PTX; 1 μg/animal) was used as an additional adjuvant. In some experiments Lewis rats were injected in the hind footpad with 75 μg of BSA along with CFA and purified PTX. Animals were examined daily between days 7 and 30 after injection for clinical signs of uveitis using slit lamp biomicroscopy and EAAU was graded in a masked fashion.11 Eyes were harvested from MAA-injected rats at various time points for histologic analysis to assess the course and severity of inflammation. The intensity of uveitis was histologically scored in a masked fashion on an arbitrary scale of 0 to 4.11

Adoptive Transfer of EAAU

Adoptive transfer of EAAU was performed as previously described by us.13–14 MAA-injected animals were divided into three groups, each containing five animals. Donor Lewis rats in group 3 received CVF at day 9 after immunization. Donor animals in groups 1 and 2 received a similar injection of sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Donor rats from each group were killed at day 11 after immunization and popliteal lymph nodes (LNs) were harvested separately. A single cell suspension of LN cells was prepared in Dulbecco’s modified minimum essential medium (DMEM) and T cells were purified on immunocolumns (Cellect; Millenium Biologix Corp., Kingston, Ontario, Canada) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Purified T cells obtained from donor animals in group 1 were cultured in vitro with antigen for 3 days in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS before transfer to naïve syngeneic host. However, purified T cells obtained from the donor animals in groups 2 and 3 were cultured in vitro with antigen for 3 days in serum-free DMEM supplemented with ITS+1 culture supplement before transfer to naïve syngeneic host. Recipient animals in group 2 received CVF 24 hours before the cell transfer. Animals in groups 1 and 3 received a similar injection of sterile PBS. Ten million cells were transferred by intraperitoneal injection. These experiments were repeated three times with similar results.

Sample Collection and Total Hemolytic Complement Activity

The intraocular tissues were prepared as described elsewhere.15 They comprised uvea, retina, aqueous humor, and vitreous and were used for total RNA extraction, ELISA, and Western blot analysis. Blood was collected by cardiac puncture, and total hemolytic complement activity in serum was determined using sensitized sheep erythrocytes (Diamedix, Miami, FL) according to the manufacturer’s directions. Serum obtained from naïve Lewis rat was used to determine the 100% value for complement-dependent serum hemolytic activity.

Complement Depletion

To deplete complement in vivo, animals were divided into five groups. Lewis rats in each group received a single intraperitoneal injection of purified CVF (35 units, 500 μL) 24 hours before immunization or at day 4, 9, 14, or 19 after immunization with MAA. Control animals received 500 μL of sterile PBS. Total hemolytic complement activity in serum was determined as described earlier.

Immunohistochemistry

Five-μm paraffin-embedded sections were immunostained with FITC-labeled monoclonal antibodies (1:100) directed against ICAM-1 and LECAM-1. Mouse anti-rat CD11b (1:200) and FITC-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG2a was used to stain complement receptor 3 (CR3) on the infiltrating cells. Control stains were performed with nonrelevant antibodies of the same immunoglobulin subclass at concentrations similar to those of the primary antibodies. Sections were examined under a fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc., Thornwood, NY).

Reverse Transcription–Polymerase Chain Reaction

Eyes were harvested from Lewis rats killed at different time points during EAAU. Intraocular tissue prepared as described earlier was pooled separately for each time point (n = 6 eyes/time point). Total RNA (0.1 μg) isolated from pooled intraocular tissue using SV total RNA isolation kit (Promega, Madison, WI) was used to detect the mRNA levels of β-actin, IFN-γ, IL-10, and IP-10 by semiquantitative RT-PCR, using reagents purchased from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). The sense and antisense oligonucleotide primers (Table 1) were synthesized at Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). Polymerase chain reaction was preformed for 25 cycles. All reactions were normalized for β-actin expression. The negative controls consisted of omission of RNA template or reverse transcriptase from the reaction mixture.

Table 1.

Primer Sequences Used in RT-PCR

| Protein | Primer | Sequence | Amplified cDNA (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-Actin | Forward | GCG-CTC-GTC-GTC-GAC-AAC-GG | 335 |

| Reverse | GTG-TGG-TGC-CAA-ATC-TTC-TCC | ||

| IL-10 | Forward | AAG-GAC-CAG-CTG-GAC-AAC-AT | 292 |

| Reverse | AGA-CAC-CTT-TGT-CTT-GGA-GCT-TA | ||

| IFN-γ | Forward | ATC-TGG-AGG-AAC-TGG-CAA-AAG-GAC-G | 288 |

| Reverse | CCT-TAG-GCT-AGA-TTC-TGG-TGA-CAG-C | ||

| IP-10 | Forward | TTC-CTG-CAA-GTC-TAT-CCT-GTC-CGC | 560 |

| Reverse | TTT-GCC-ATC-TCA-CCT-GGA-CTG |

The sequences of all oligonucleotides are shown in the 5′ to 3′ direction.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

Eyes were harvested from Lewis rats killed at different time points during EAAU. Intraocular tissue prepared as described earlier was pooled separately for each time point (n = 6 eyes/time point) and homogenized in 500 μL of ice-cold PBS containing protease inhibitors.15 After centrifugation, the supernatant was assayed (in triplicate) for rat IL-10 protein using rat ELISA kits from Biosource International (Camarillo, CA). Rat IFN-γ was assayed with a rat ELISA kit from R&D systems, Inc. (Minneapolis, MN). Cytokine concentrations in the test samples were calculated by comparison with a corresponding standard curve, and all results were expressed as the mean concentration (picograms per milligram protein) of cytokine ± SD. These experiments were repeated three times with similar results.

Western Blot Analysis

The sample was prepared as described for the ELISA. After SDS-PAGE on a 12% linear slab gel (10 μg total protein/lane), under reducing conditions, separated proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane.15 Blots were incubated with the IgG fraction of goat anti-rat C3 or the IgG fraction of rabbit anti-rat IP-10. Control blots were treated with the same dilution of goat or rabbit IgG isotype control, respectively. After washing and incubation with horse-radish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody, blots were developed with an enhanced chemiluminescence Western blot analysis detection system (ECL Plus; GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). Quantification of iC3b was accomplished by analyzing the intensity of the bands on computer (Quantity One 4.2.0; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, CA).

In Vivo Antibody Treatment

MAA injected Lewis rats (group 1, n = 5) received a single injection of 0.5 mg of mouse anti-rat CR3 (OX42) intraperitoneally daily, from day 9 to 14 after immunization. Control animals in groups 2 (n = 5) and 3 (n = 5) received a similar treatment with isotype matched monoclonal antibody and PBS alone, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

Differences between groups were evaluated by Student’s t-test. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Ocular Complement Activation and EAAU

MAA injected Lewis rats were killed at different time points (n = 6/each time point): days 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 19, 23, and 30. The presence of the C3 activation product iC3b within the eye at these time points was investigated by semiquantitative Western blot analysis and was used as the measure of ocular complement activation. The 68- and 43-kDa α-chains of iC3b were identified on Western blot in normal eyes and in the eyes of MAA-injected animals killed at different time points. The blot incubated with goat IgG isotype control antibody did not show any immunoreactivity (data not shown).

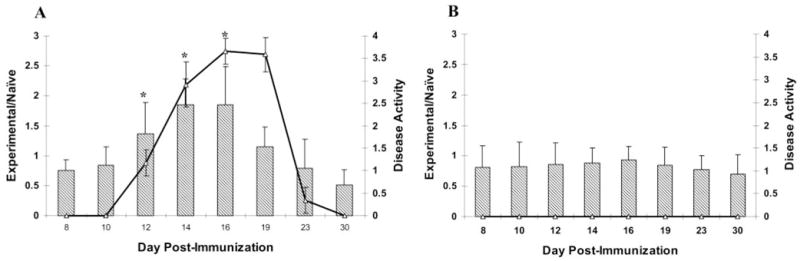

Densitometric analysis of these polypeptide chains indicated that the levels of iC3b within the eye paralleled the course of the disease. On days 8 to 10, low levels of iC3b were detected in the eyes of MAA-injected rats, similar to naïve animals. Levels of iC3b increased markedly in MAA-immunized animals on days 12 to 16 after immunization and returned to baseline during the resolution of EAAU (Fig. 1A). On days 12 to 16, the intraocular levels of iC3b in MAA-immunized rats were significantly higher (P < 0.05) than other time points—specifically, days 8, 10, 19, 23, and 30 (Fig. 1A). In contrast, with a nonrelevant antigen, BSA, only low levels (similar to those in naïve rats) of iC3b were detected in the eyes of BSA-injected animals at all time points (Fig. 1B). Intraocular inflammation was not observed in BSA-injected rats (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Relationship between ocular complement activation and disease activity in EAAU. Semiquantitative Western blot and densitometric analyses of polypeptide chains corresponding to iC3b was used to measure intraocular complement activation after immunization of Lewis rats with MAA and BSA. The intensity of the iC3b protein bands was quantitated, and the relative intensity was expressed as ratio of the intensity of the bands from the experimental (MAA- or BSA-injected) animals to those of the naïve rats (experimental/naïve). In animals immunized with MAA, the levels of iC3b within the eye paralleled the course of disease in EAAU (A). In these rats there was a significant increase in the levels of iC3b at days 12 to 16 compared with days 8, 10, 23, and 30. Low levels (similar to naïve rats) of iC3b were detected in the eyes of BSA-injected animals at all time points (B). The bar charts represent the relative intensity of iC3b bands and the line chart shows the disease activity in MAA- (A) and BSA-injected (B) rats. Data are presented as the mean ± SD and are representative of six independent experiments. *P < 0.05.

Effect of Systemic Complement Depletion on EAAU

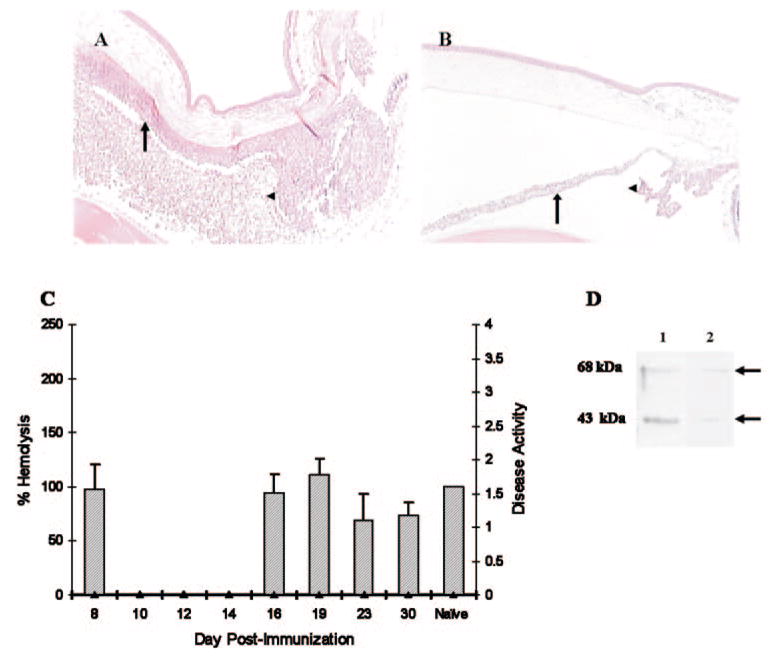

A single injection of CVF was given at five different time points as described in the Materials and Methods section. Complement depletion 24 hours before immunization or at day 4 after immunization did not alter the course of EAAU (Table 2). Of note, the incidence, duration, and severity of disease (determined both clinically and histologically) was dramatically reduced in rats treated with CVF on day 9 after immunization compared with that in control rats (Table 2; Figs. 2A, 2B). In these animals a single injection of CVF on day 9 after immunization resulted in complete depletion of complement for 5 days (Fig. 2C). Low levels of iC3b were detected within the eye of MAA-injected, CVF-treated animals on days 16 (data not shown), 19 (Fig. 2D), 23, and 30 (data not shown). In contrast, complement depletion after the onset of inflammation (day 14 or 19) did not affect EAAU (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effect of Complement Depletion on EAAU

| Eyes with EAAU

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAA (μg) | Incidence | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Day of Onset | Duration of Disease (d) | |

| Control | 100 | 30/30 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 14.0 ± 2.0 | 13.0 ± 1 |

| CVF (day − 1) | 100 | 30/30 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 14.5 ± 1 | 13.0 ± 2 |

| CVF (day 4) | 100 | 30/30 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 14.0 ± 1 | 12.0 ± 1 |

| CVF (day 9) | 100 | 2/30 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 19.5 ± 1.0 | 2–3* |

| CVF (day 14) | 100 | 30/30 | 1 | 0 | 29 | 15.5 ± 2.0 | 12.0 ± 2 |

| CVF (day 19) | 100 | 30/30 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 14.0 ± 1 | 13.0 ± 1 |

Incidence of EAAU given as positive/total eyes following clinical examination. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. Severity of inflammation on histopathologic examination was grouped as mild (1+), moderate (2+ to 3+) or severe (4+). This experiment was repeated three times (n = 5 rats/experiment) with similar results.

P < 0.05.

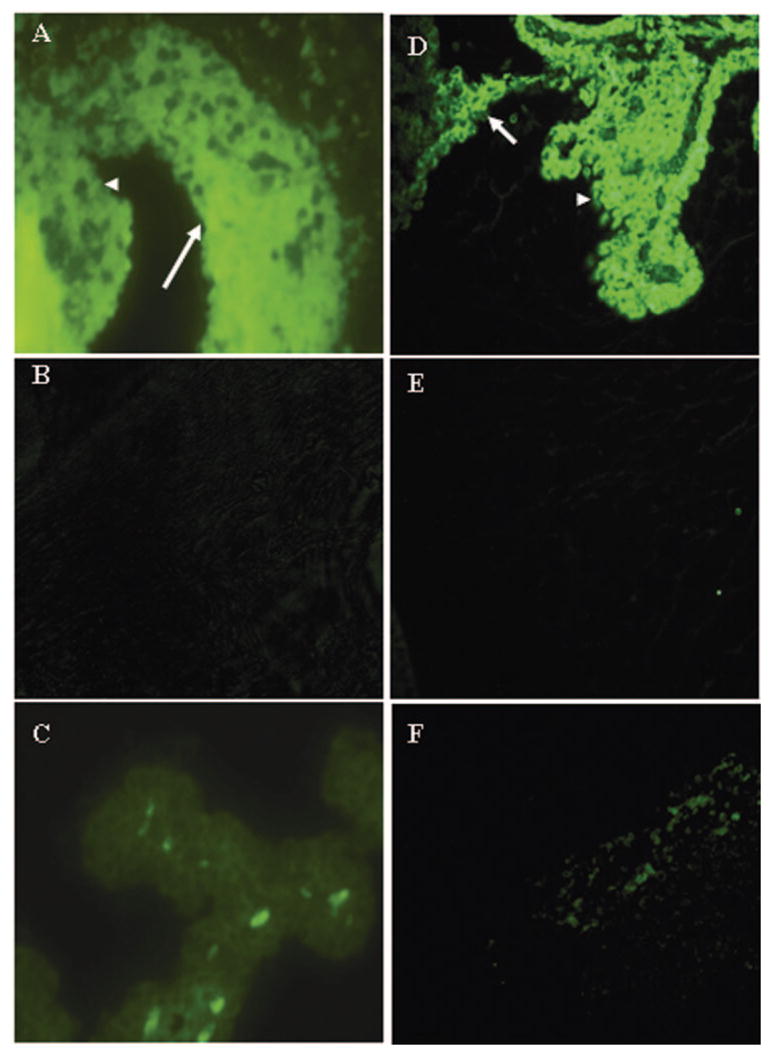

Figure 2.

Effect of CVF on EAAU. Lewis rats immunized with MAA received a single intraperitoneal injection of PBS (A) or CVF (B) at day 9 and were killed at the peak of EAAU (day 19 after immunization) to study the effect of complement depletion on histopathological changes within the eye. Severe EAAU was observed in the MAA-injected complement-sufficient (PBS-treated) animals (A). The anterior chamber, the iris (arrow), and the ciliary body (arrowhead) were infiltrated by inflammatory cells. EAAU did not develop in complement-depleted (CVF-treated) Lewis rats immunized with MAA (B). Mag-nification, ×20. A single intraperitoneal injection of CVF in MAA-injected (C) rats resulted in almost complete complement depletion for 5 days. In these animals, serum complement activity returned to the basal levels on day 16 and remained at this level on days 19 to 30. Disease activity in these animals was zero. The bar charts represent serum complement activity and the line chart shows the disease activity (C). C3 split products in the eye of naïve (lane 1) and MAA-injected, CVF-treated (lane 2) rats at day 19 after immunization (D). The data shown are representative results in three different experiments.

Effect of Systemic Complement Depletion on Adoptive Transfer EAAU

Ten million in vitro–primed T cells isolated from the draining lymph nodes of Lewis rats killed at day 11 after immunization transferred EAAU to naïve syngeneic rats (group 1, Table 3). These cells were cultured in the presence of complement. In contrast, EAAU was completely suppressed when in vitro–primed-T cells cultured in the absence of complement were transferred to a CVF-treated, complement-depleted host (group 2, Table 3). Furthermore, T cells obtained from MAA-sensitized Lewis rats treated with CVF on day 9 after immunization and cultured for three days in the absence of complement did not transfer EAAU to naïve syngeneic rats (group 3, Table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of Complement on the Adoptive Transfer EAAU

| Cells Transferred to Recipients

|

EAAU in Recipients

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Donor Treatment | Recipient Treatment | Number of Cells (106) | Cell Population | Incidence | Score | Day of Onset |

| 1 | None | None | 10 | T lymphocytes | 30/30 | Severe | 7 ± 1 |

| 2 | None | CVF | 10 | T lymphocytes | 0/30 | — | — |

| 3 | CVF | None | 10 | T lymphocytes | 0/30 | — | — |

Donors were treated with CVF at day 9 after immunization. Cells were transferred intraperitoneally. Incidence of EAAU given as positive/total eyes after clinical examination. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. Severity of inflammation on histopathologic examination was grouped as mild (1+), moderate (2+ to 3+) or severe (4+). These experiments were repeated three times (n = 5 rats/experiment) with similar results.

These results suggest that complement is critical for the development of EAAU induced by either active immunizations or the transfer of in vitro–primed antigen-specific T cells.

Effect of Systemic Complement Depletion on Intraocular Cytokine and Chemokine Production

Lewis rats immunized with MAA were divided in two groups: One group received a single injection of CVF on day 9; the control group received PBS on the same day. Animals (n = 6/time point in each group) were killed at days 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 19, 23, and 30 after immunization, and the eyes were harvested.

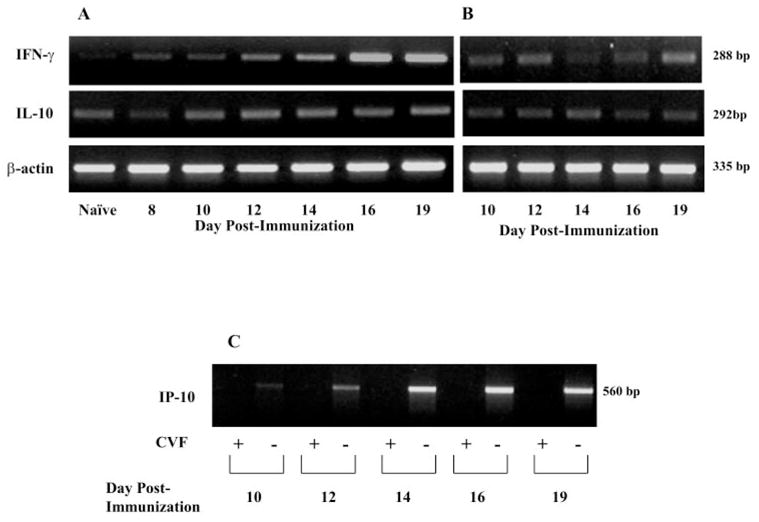

Using semiquantitative RT-PCR, we detected low levels of IFN-γ transcripts in the eyes of naïve animals, as well as on days 8 and 10 in complement-sufficient MAA immunized rats (Fig. 3A). In the presence of complement, IFN-γ transcripts within the eye increased on day 12, peaked on days 16 to 19 (Fig. 3A), returned to basal levels by day 23, and remained at this level on day 30 (data not shown). In contrast, IFN-γ mRNA remained at low levels at all time points in complement-depleted rats (Fig. 3B). IL-10 mRNA (Fig. 3A) increased modestly on day 10, reached maximum levels on days 12 to 19, and returned to basal levels by day 30 (data not shown) in complement-sufficient rats. In contrast, complement depletion resulted in decreased IL-10 mRNA levels within the eye at each time point (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Effect of systemic complement depletion on intraocular IFN-γ, IL-10, and IP-10 mRNA expression during EAAU. Eyes (n = 6/time point) were harvested from MAA-injected, complement-sufficient (PBS-treated) and -depleted (CVF-treated) Lewis rats killed at different time points for semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis. PCR products were analyzed on a 2% agarose gel. (A) mRNA expression of IFN-γ and IL-10 in complement-sufficient, MAA-injected rats, and (B) represents mRNA expression of these cytokines in complement-depleted, MAA-injected rats. (C) shows IP-10 mRNA expression in both CVF- and PBS-treated, MAA-injected rats. There was decreased production of IFN-γ and IL-10 mRNA in complement-depleted animals (B) compared with complement-sufficient rats (A). IP-10 mRNA expression was abolished by CVF treatment (C). A strong band at 335 bp for β-actin indicated an equal amount of RNA in each lane (A, B). Shown are ethidium-bromide–stained bands for PCR products after UV exposure. Images are representative of results in three independent experiments.

In the presence of complement, low levels of IP-10 transcripts were observed on day 10 (Fig. 3C). mRNA levels of IP-10 increased on day 12, peaked on days 14 to 19 (Fig. 3C), and returned to basal levels on day 23 (data not shown). In contrast, in the absence of complement, mRNA for IP-10 was not detected at all time points studied (Fig. 3C). No bands were detected in the control experiments without RNA or reverse transcriptase (data not shown).

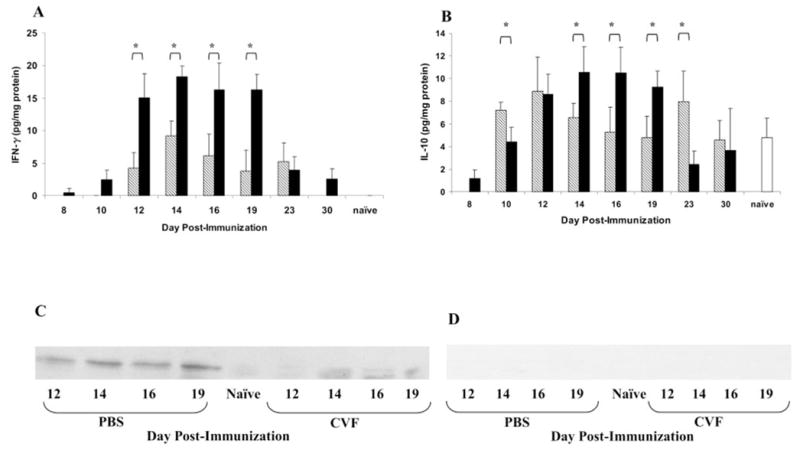

ELISA results (Fig. 4) demonstrated that IFN-γ protein levels increased dramatically on day 12, peaked on day 14, and returned to basal levels by day 30 in MAA-immunized, complement-sufficient rats (Fig. 4A). Complement depletion resulted in undetectable levels of IFN-γ protein on day 10, significantly reduced levels on days 12 to 19 (P < 0.05), and undetectable levels on day 30 (Fig. 4A). In complement-sufficient, MAA-immunized rats, the maximum increase of IL-10 protein was observed on days 14 to 16, with a gradual decline during the resolution of EAAU (Fig. 4B). A time course study showed that, in complement-depleted rats, the levels of IL-10 protein on days 14 to 19 were significantly lower (P < 0.05) than those in complement-sufficient animals (Fig. 4B). IL-10 protein was not detected in complement-depleted animals on day 8 but was higher than complement-sufficient rats on days 10 and 23 (P < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Effect of complement on intraocular IFN-γ, IL-10, and IP-10 protein production during EAAU. Eyes (n = 6/time point) were harvested from MAA-injected, complement-sufficient (■) and complement-depleted (▧) rats killed at different time points, and cytokine production was assessed by protein-specific ELISA. Compared with complement-sufficient rats, IFN-γ (A) and IL-10 (B) protein levels in complement-depleted rats were significantly reduced on days 12 to 19 and days 14 to 19, respectively. Results shown are the mean ± SD of results in triplicate independent analyses. *P < 0.05. (C). On Western Blot analysis, IP-10 was barely detected in complement-depleted Lewis rats compared with complement-sufficient animals. Control blot incubated with equivalent concentration of irrelevant antibody (rabbit IgG isotype control) did not show any reactivity (D). (C, D) Representative of results in three separate experiments.

Western blot analysis revealed low constitutive levels of IP-10 protein on day 10 after immunization in MAA-immunized, complement-sufficient rats (data not shown). IP-10 protein levels increased on day 12, peaked on days 14 to 19 (Fig. 4C), and were very low on days 23 to 30 in these rats (data not shown). In contrast IP-10 protein was barely detectable in complement-depleted rats at all time points (Fig. 4C). Control blots incubated with the rabbit IgG isotype control did not show any reactivity (Fig. 4D).

Expression of Cell Adhesion Molecules in Complement-Depleted Animals

We also studied the effect of complement depletion on the intraocular expression of ICAM-1 and LECAM -1 at the peak of EAAU, with immunofluorescence microscopy. MAA-immunized Lewis rats, with and without CVF treatment, were killed on day 19. Both ICAM-1 and LECAM-1 were very strongly expressed on the iris and ciliary body of complement-sufficient rats on day 19 (Figs. 5A, 5D). However, both the adhesion molecules were markedly suppressed in CVF-treated animals at this time point (Figs. 5B, 5E). Low constitutive levels of ICAM-1 (Fig. 5C) and LECAM-1 (Fig. 5F) were observed in naïve rat eye. The sections in which isotype control antibodies were substituted for the primary antibodies were negative (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Effect of complement depletion on the ocular expression of ICAM-1 and LECAM-1 at the peak of EAAU. Paraffin-embedded sections were prepared from eyes harvested from MAA-injected, complement-sufficient (A, D) and complement-depleted (B, E) Lewis rats at day 19 after immunization (the peak of EAAU). (C, F) Images from naïve animals. Sections were stained with FITC-labeled monoclonal antibodies against ICAM-1 (A–C) and LECAM-1 (D–F). At the peak of EAAU, strong expression of ICAM-1 (A) and LECAM-1 (D) was observed on the iris (arrow) and the ciliary body (arrowhead). Expression of these adhesion molecules was suppressed in complement-depleted rats (B, E). Weak staining for ICAM-1 (C) and LECAM-1 (F) was detected in naïve rat eye. Each micrograph is representative of imaging in three separate experiments. Magnification, × 40.

Role of iC3b and CR3 Interaction in EAAU

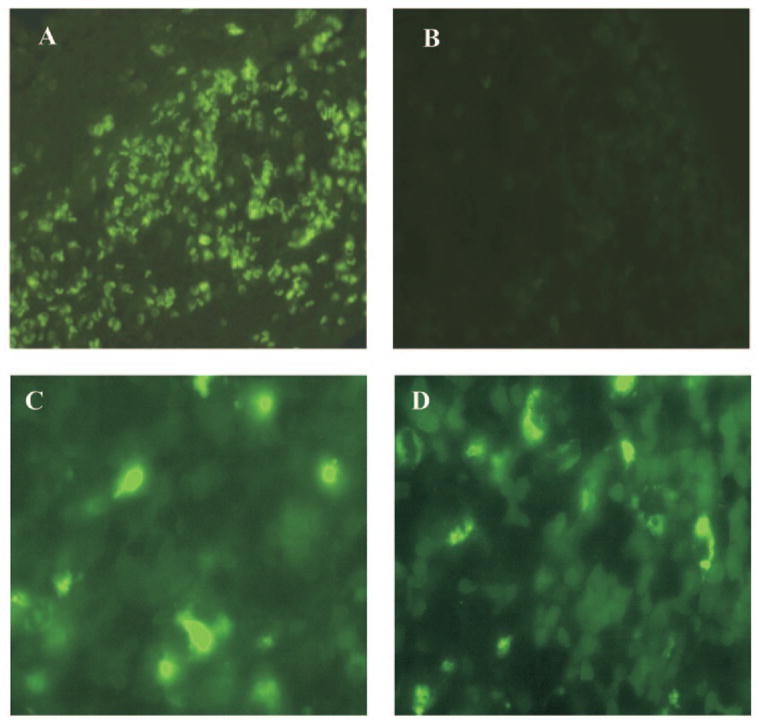

The eyes of MAA immunized animals killed at various time points (days 14, 16, 18, and 19) were stained with anti-rat CD11b (OX-42). This antibody is specific for the ligand binding site of CR3 (type 3 complement receptor) and inhibits the binding of iC3b to CR3.4,16 We observed the infiltration of CR3-positive cells within the iris, ciliary body, and anterior chamber on days 14 and 16 (data not shown) with massive infiltration on days 18 to 19 (Fig. 6A). No fluorescence was detected in the eyes of naïve rats (data not shown) and the sections stained with isotype control antibodies (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

CR3 staining during EAAU (A). Eyes harvested from complement-sufficient Lewis rats killed at the peak of EAAU (day 19 after immunization) were stained with OX-42 (anti-CR3). Strong expression of CR3 by infiltrating cells at the peak of disease was observed (A). No fluorescence was detected in the sections stained with isotype control antibody (B). CR3-positive cells in the spleen of naïve Lewis rat injected with PBS (C) and OX-42 (D). Magnification: (A, B) × 40; (C, D) × 100.

The in vivo effect OX-42 on EAAU was investigated and MAA-immunized rats were given intraperitoneal injections of this monoclonal antibody. We observed that anti-CR3 treatment before the onset of inflammation (day 9, group 1) significantly (P < 0.05) reduced the severity of EAAU compared with isotype-matched, PBS-treated control subjects (Table 4). The duration of the disease was also significantly (P < 0.05) reduced in OX-42-treated animals compared with the control subjects (Table 4). This effect of OX-42 on EAAU was not due to the cytotoxic activity of the antibody and/or immune complexes, because the number of CR3-positive cells in the liver, kidney (data not shown), and spleen (Fig. 6) of rats after daily intraperitoneal injection of OX-42 for 6 days were similar to those injected with PBS (Figs. 6C, 6D).

Table 4.

Effect of Antibodies against Complement Receptor 3 (OX-42) on EAAU

| Eyes with EAAU

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Host Treatment | MAA (μg) | Incidence | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Day of Onset | Duration of Disease (d) |

| PBS | 100 | 10/10 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 14.0 ± 2.0 | 13.0 ± 1.0 |

| Isotype control | 100 | 10/10 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 14.0 ± 1.0 | 13.0 ± 0.5 |

| OX-42 | 100 | 10/10 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 15.0 ± 1.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0* |

Incidence of EAAU given as positive/total eyes after clinical examination. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. Severity of inflammation on histopathologic examination was grouped as mild (1+), moderate (2+ to 3+) or severe (4+).

P < 0.05.

Discussion

Experimental autoimmune anterior uveitis (EAAU) is an auto-immune disease of the eye10–14 that closely resembles human idiopathic anterior uveitis. We used this model to explore the role of complement in the pathogenesis of ocular autoimmune disease. The data presented herein demonstrate a strong relationship between the presence–activation of complement with disease activity, as well as the expression of cytokines, chemokines and adhesion molecules during EAAU. To the best of our knowledge this relationship has not been established previously in any type of ocular autoimmune disease.

We identified significantly increased levels of iC3b, a cleavage product of C3, within the eye during the peak of EAAU. Because activation of the complement system is necessary for the generation of C3 split products,1,17 their increased levels within the eye of MAA-immunized rats provided indisputable evidence of local complement activation during EAAU. The antigen specificity of this observation was investigated with an irrelevant antigen (BSA). The animals immunized with BSA had low levels of ocular iC3b which was similar to those in naïve rat eye. We have shown that low levels of iC3b are present in normal rat eye.15 Taken together these results support the hypothesis that the local complement activation contributes to intraocular inflammation in EAAU.

Decomplementation of MAA-immunized Lewis rats before the onset of clinical inflammation suppressed EAAU. Of interest, complement activity in these complement-depleted rats on days 10 to 14 (i.e., during induction of EAAU) was undetectable. Complement depletion also resulted in the suppression of uveitis in adoptive transfer EAAU. These results support a central role for complement in the development of EAAU.

Complement deficiency has been reported to ameliorate various experimental autoimmune diseases.18–23 We have recently shown that activation of complement, specifically the formation of MAC, is essential for the development of laser-induced choroidal angiogenesis in mice.24

We next sought to determine how complement depletion suppressed EAAU and compared the expression of cytokines, chemokines, and adhesion molecules within the eye of both complement-sufficient and complement-depleted animals during EAAU. We studied the expression of IFN-γ, IL-10, IP-10, ICAM-1, and LECAM-1 because of their important role in the pathogenesis of various autoimmune diseases including uveitis.12,25–31 Furthermore, several studies have suggested that the expression of these cytokines, chemokines, and adhesion molecules is affected by the presence and activation of the complement system.32–41

A time course analysis of the expression of cytokines and chemokines within the eye of both complement-sufficient and -depleted rats revealed that there was a decreased production of IFN-γ, IL-10, and IP-10 in complement-depleted animals. These results imply that the release of these inflammatory mediators during EAAU was complement dependent. It has been reported by us4 and others42–44 that complement is essential for the production of cytokines such as IL-10 by antigen-presenting cells and monocytes. Analysis of cell adhesion molecule expression revealed that ICAM-1 and LECAM-1 were significantly decreased after complement depletion, indicating that these molecules are regulated by complement.

We then focused our attention on iC3b, because we noticed that the levels of iC3b were elevated in the rat eye during EAAU. The systemic injection of anti-CR3 (MRC OX-42) had a significant protective effect on EAAU, thus suggesting that the interaction of iC3b with CR3 was involved in the development of EAAU. Similar to our observations, several studies with different animal models have reported that treatment with anti-CR3 antibodies diminishes the severity of various experimental diseases.45–47 In our experiments, EAAU was not completely inhibited by anti-CR3 treatment. This may be due to the possible role of other complement activation products and receptors19–21,24,32 in EAAU.

In summary, we have demonstrated that the expression of cytokines, chemokines, and adhesion molecules necessary for the development of EAAU requires availability and activation of complement. Interference in the availability of complement by systemic depletion leads to the suppression of disease. Furthermore, the interaction between iC3b and CR3 plays an important role in EAAU. Thus, complement inhibition and/or treatment with anti-CR3 antibodies may be a novel therapy for autoimmune uveitis.

Footnotes

Supported in part by National Eye Institute Grants EY13335, EY014623, and R24 EY015636; the Commonwealth of Kentucky Research Challenge Trust Fund; and Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc.

Disclosure: P. Jha, None; J.-H. Sohn, None; Q. Xu, None; H. Nishihori, None; Y. Wang, None; S. Nishihori, None; B. Manickam, None; H.J. Kaplan, None; P.S. Bora, None; N.S. Bora, None

References

- 1.Thomlinson S. Complement defense mechanisms. Curr Opin Immunol. 1993;5:83–89. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(93)90085-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dempsey PW, Allison MED, Akkaraju S, Goodnow CC, Fearon DT. C3d of complement as a molecular adjuvant: bridging innate and acquired immunity. Science. 1996;271:348–350. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5247.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carroll MC. The complement system in regulation of adaptive immunity. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:981–986. doi: 10.1038/ni1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sohn JH, Bora PS, Suk HJ, Molina H, Kaplan HJ, Bora NS. Tolerance is dependent on complement C3 fragment iC3b binding to antigen-presenting cells. Nat Med. 2003;9:206–212. doi: 10.1038/nm814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pasinetti GM. Inflammatory mechanisms in neurodegeneration and Alzheimer’s disease: the role of the complement system. Neurobiol Aging. 1996;17:707–716. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(96)00113-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D’Ambrosio AL, Pinsky DJ, Connolly ES. The role of the complement cascade in ischemia/reperfusion injury: implications for neuroprotection. Mol Med. 2001;7:367–382. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singhrao SK, Neal JW, Morgan BP, Gasque P. Increased complement biosynthesis by microglia and complement activation on neurons in Huntington’s disease. Exp Neurol. 1999;159:362–376. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klein MA, Kaeser PS, Schwarz P, et al. Complement facilitates early prion pathogenesis. Nat Med. 2001;7:488–492. doi: 10.1038/86567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prineas JW, Kwon EE, Cho ES, et al. Immunopathology of secondary-progressive multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2001;50:646–657. doi: 10.1002/ana.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Broekhuyse RM, Kuhlman ED, Winkens HJ, Van Vugt AHM. Experimental autoimmune anterior uveitis (EAAU), a new form of experimental uveitis: I. Induction by a detergent-insoluble, intrinsic protein fraction of the retina pigment epithelium. Exp Eye Res. 1991;52:465–474. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(91)90044-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bora NS, Kim MC, Kabeer NH, et al. Experimental autoimmune anterior uveitis: induction with melanin-associated antigen from the iris and ciliary body. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995;36:1056–1066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim MC, Kabeer NH, Tandhasetti MT, Kaplan HJ, Bora NS. Immunohistochemical studies in melanin associated antigen (MAA) induced experimental autoimmune anterior uveitis (EAAU) Curr Eye Res. 1995;14:703–710. doi: 10.3109/02713689508998498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bora NS, Woon MD, Tandhasetti MT, Cirrito TP, Kaplan HJ. Induction of experimental autoimmune anterior uveitis by a self-antigen: melanin complex without adjuvant. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997;38:2171–2175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bora NS, Sohn JH, Kang SG, et al. Type I collagen is the autoantigen in experimental autoimmune anterior uveitis. J Immunol. 2004;172:7086–7094. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.11.7086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sohn JH, Kaplan HJ, Suk HJ, Bora PS, Bora NS. Chronic low level complement activation within the eye is controlled by intraocular complement regulatory proteins. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:3492–3502. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robinson AP, White TM, Mason DW. Macrophage heterogeneity in the rat as delineated by two monoclonal antibodies MRC OX-41 and MRC OX-42, the latter recognizing complement receptor type 3. Immunology. 1986;57:239–247. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis AE, 3rd, Harrison RA, Lachmann PJ. Physiologic inactivation of fluid phase C3b: isolation and structural analysis of C3c, C3d,g (alpha 2D), and C3g. J Immunol. 1984;132:1960–1966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaede KI, Baumeister E, Heesemann J. Decomplementation by cobra venom factor suppresses Yersinia-induced arthritis in rats. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3697–3701. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3697-3701.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hietala MA, Jonsson IM, Tarkowski A, Kleinau S, Pekna M. Complement deficiency ameliorates collagen-induced arthritis in mice. J Immunol. 2002;169:454–459. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tran GT, Hodgkinson SJ, Carter N, Killingsworth M, Spicer ST, Hall BM. Attenuation of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis in complement component 6-deficient rats is associated with reduced complement C9 deposition, P-selectin expression, and cellular infiltrate in spinal cords. J Immunol. 2002;168:4293–4300. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vriesendorp FJ, Flynn RE, Malone MR, Pappolla MA. Systemic complement depletion reduces inflammation and demyelination in adoptive transfer experimental allergic neuritis. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1998;95:297–301. doi: 10.1007/s004010050801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marak GE, Wacker WB, Rao NA, Jack R, Ward PA. Effects of complement depletion on experimental allergic uveitis. Ophthalmic Res. 1979;11:97–107. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaya Z, Afanasyeva M, Wang Y, et al. Contribution of the innate immune system to autoimmune myocarditis: a role for complement. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:739–745. doi: 10.1038/90686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bora PS, Sohn JH, Cruz JM, et al. Role of complement and complement membrane attack complex in laser-induced choroidal neovascularization. J Immunol. 2005;174:491–497. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.1.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adorini L. Cytokine-based immunointervention in the treatment of autoimmune diseases. Clin Exp Immunol. 2003;132:185–192. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02144.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cameron MJ, Kelvin DJ. Cytokines and chemokines: their receptors and their genes—an overview. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003;520:8–32. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0171-8_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wallace GR, John Curnow S, Wloka K, Salmon M, Murray PI. The role of chemokines and their receptors in ocular disease. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2004;23:435–448. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsunoda I, Lane TE, Blackett J, Fujinami RS. Distinct roles for IP-10/CXCL10 in three animal models, Theiler’s virus infection, EAE, and MHV infection, for multiple sclerosis: implication of differing roles for IP-10. Mult Scler. 2004;10:26–34. doi: 10.1191/1352458504ms982oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anderson ME, Siahaan TJ. Targeting ICAM-1/LFA-1 interaction for controlling autoimmune diseases: designing peptide and small molecule inhibitors. Peptides. 2003;24:487–501. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(03)00083-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rainer TH. L-selectin in health and disease. Resuscitation. 2002;52:127–141. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(01)00444-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fang IM, Yang CH, Lin CP, Yang CM, Chen MS. Expression of chemokine and receptors in Lewis rats with experimental autoimmune anterior uveitis. Exp Eye Res. 2004;78:1043–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Godau J, Heller T, Hawlisch H, et al. C5a initiates the inflammatory cascade in immune complex peritonitis. J Immunol. 2004;173:3437–3445. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.3437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Albrecht EA, Chinnaiyan AM, Varambally S, et al. C5a-induced gene expression in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:849–859. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63173-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jagels MA, Daffern PJ, Hugli TE. C3a and C5a enhance granulocyte adhesion to endothelial and epithelial cell monolayers: epithelial and endothelial priming is required for C3a-induced eosinophil adhesion. Immunopharmacology. 2000;46:209–222. doi: 10.1016/s0162-3109(99)00178-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vaporciyan AA, Mulligan MS, Warren JS, Barton PA, Miyasaka M, Ward PA. Up-regulation of lung vascular ICAM-1 in rats is complement dependent. J Immunol. 1995;155:1442–1449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Monsinjon T, Gasque P, Chan P, Ischenko A, Brady JJ, Fontaine MC. Regulation by complement C3a and C5a anaphylatoxins of cytokine production in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. FASEB J. 2003;17:1003–1014. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0737com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jauneau AC, Ischenko A, Chan P, Fontaine M. Complement component anaphylatoxins upregulate chemokine expression by human astrocytes. FEBS Lett. 2003;537:17–22. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahamed J, Venkatesha RT, Thangam EB, Ali H. C3a enhances nerve growth factor-induced NFAT activation and chemokine production in a human mast cell line, HMC-1. J Immunol. 2004;172:6961–6968. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.11.6961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tramontini NL, Kuipers PJ, Huber CM, et al. Modulation of leukocyte recruitment and IL-8 expression by the membrane attack complex of complement (C5b-9) in a rabbit model of antigen-induced arthritis. Inflammation. 2002;26:311–319. doi: 10.1023/a:1021420903355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Papagianni AA, Alexopoulos E, Leontsini M, Papadimitriou M. C5b-9 and adhesion molecules in human idiopathic membranous nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:57–63. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grant EP, Picarella D, Burwell T, et al. Essential role for the C5a receptor in regulating the effector phase of synovial infiltration and joint destruction in experimental arthritis. J Exp Med. 2002;196:1461–1471. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Karp CL, Wysocka M, Wahl LM, et al. Mechanism of suppression of cell-mediated immunity by measles virus. Science. 1996;273:228–231. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5272.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yoshida Y, Kang K, Berger M, et al. Monocyte induction of IL-10 and down-regulation of IL-12 by iC3b deposited in ultraviolet-exposed human skin. J Immunol. 1998;161:5873–5879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Luo X, Liu L, Tang N, et al. Inhibition of monocyte-derived dendritic cell differentiation and interleukin-12 production by complement iC3b via a mitogen-activated protein kinase signalling pathway. Exp Dermatol. 2005;14:303–310. doi: 10.1111/j.0906-6705.2005.00325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gordon EJ, Myers KJ, Dougherty JP, Rosen H, Ron Y. Both anti-CD11a (LFA-1) and anti-CD11b (MAC-1) therapy delay the onset and diminish the severity of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neuroimmunol. 1995;62:153–160. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(95)00120-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Palmen MJ, Dijkstra CD, van der Ende MB, Pena AS, van Rees EP. Anti-CD11b/CD18 antibodies reduce inflammation in acute colitis in rats. Clin Exp Immunol. 1995;101:351–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1995.tb08363.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnson LL, Gibson GW, Sayles PC. CR3-dependent resistance to acute Toxoplasma gondii infection in mice. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1998–2003. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.1998-2003.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]