Abstract

The extracellular matrix (ECM) plays a critical role in governing cell behavior and phenotype during limb skeletogenesis. Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (Cspgs) are highly expressed in the ECM of precartilage mesenchymal condensations and are important to limb chondrogenesis and cartilage structure, but little is known regarding their involvement in formation of synovial joints in the embryonic limb. Matrix versican Cspg expression has previously been reported in the epiphysis of developing long bones and presumptive joint; however, detailed analysis has not yet been conducted. In the present study we immunolocalized versican and aggrecan Cspgs during chick elbow joint morphogenesis between HH st25-41 of development. In this study we show that versican and aggrecan expression initially overlapped in the incipient cartilage model of long bones in the wing, but versican was also highly expressed in the perichondrium and presumptive joint interzone during early stages of morphogenesis (HH st25-34). By HH st36-41 versican localization was restricted to the future articular surfaces of the developing joint and surrounding joint capsule while aggrecan localized in an immediately adjacent and predominately non-overlapping region of chondrogenic cells at the epiphyses. These results suggest a potential role for versican proteoglycan in development and maintenance of the synovial joint interzone.

Keywords: versican, synovial joint morphogenesis, chick embryo, extracellular matrix

1. Introduction

The morphogenesis of synovial joints is a complex and little understood process. At approximately HH st25 11 of chick development the densely packed mesenchymal cells of the pre-chondrogenic Y-shaped aggregate begin to differentiate and give rise to chondrocytes, the functional unit of cartilage. Type II collagen immunolocalization in the newly differentiating Y-shaped aggregate confirms that there is cartilaginous continuity across the future joint location 4. Shortly thereafter, the formation of a synovial joint at the distal end of the presumptive humerus and proximal ends of the presumptive radius and ulna separates the large aggregate into three distinct skeletal elements. The presumptive joint area, referred to as the interzone, is a three-layered structure consisting of a non-chondrogenic central lamina bordered by two chondrogenous zones from which the joint cavitates, thus separating the adjacent skeletal elements 1, 9, 20. Interzone formation is characterized by appearance of a narrow band of densely packed flattened cells 21 that cease expression of cartilage specific markers such as type II collagen and aggrecan and begin to secrete type I collagen 4.

Cell flattening in the interzone is not likely a passive process due to the growth of opposing skeletal elements; instead the interzone is thought to arise from a population of prespecified cells 13 which later express factors specific to the “joint” phenotype 9. Secreted factors implicated in regulating interzone formation include Wnt14 12, Gdf5 26, and noggin 2. In addition, the transcription factors Cux1 18, ERG-3 14 and Dlx5 and Dlx6 8 have also been implicated in this process.

Versican is a Cspg in the hyalectin family bearing chondroitin sulfate (CS) glycosaminoglycan (GAG) side chains. Versican is comprised of a core protein with globular domains at both N-terminal and C-terminal regions and central CS-attachment regions consisting of CS-α and CS-β domains 16, 34 and is predominately found in tissue with a high cell to matrix ratio 10, 16, 24. The N-terminal G1 globular domain of versican specifically binds hyaluronan (HA), an interaction that is stabilized by link-protein (LP) 19. Stable versican-HA-LP complexes are generally thought to have an anti-adhesive effect and create a loose, highly hydrated environment 17, 28, 29. These properties also suggest that versican may provide a mechanism to stabilize HA associated with cell membrane CD44: thus, forming a versican/HA pericellular matrix around the cell affecting adhesive and migratory capabilities 34.

Versican has previously been localized in limb pre-cartilage mesenchymal condensations in chick 16, 24, at the epiphyseal ends of long bones 23, 30 and in the presumptive joint in mouse 25. Ectopic versican expression has also been demonstrated to modulate chondrocyte morphology in vitro via changes in cytoskeletal structure 33; however, little else is known about versican's function in this regard. Furthermore, the temporal and spatial expression pattern of versican relative to that of its close hyalectin family relative, aggrecan has not been examined in detail during synovial joint morphogenesis. The present study provides the first report of versican expression during avian elbow joint morphogenesis and its relationship in this region to the chondrogenic markers, aggrecan and type II collagen.

2. Materials and Methods

In order to examine the expression of versican in the elbow region of the developing chick limb a minimum of 15 normal viable embryos were evaluated by immunohistochemistry on paraffin embedded sections in order to determine the most consistent expression pattern for versican during each stage along an 11 day time-course (HH st25-41). Chick embryos were harvested following IACUC approved guidelines, placed in ice-cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and fixed in 4:1 methanol:dimethylsulfoxide ON at 4oC. Fixed embryos were dehydrated through graded ethanols into xylene and embedded in paraffin.

Primary antibodies utilized included polyclonal rabbit anti-chick versican and aggrecan 31 and monoclonal mouse anti-chick type II collagen antibody (II-II6B3; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, IA). Double labeling was routinely performed with anti-versican in combination with Type II collagen antibody and in selected experiments with biotinylated hyaluronic acid binding protein (Seikagaku).

Prior to processing for immunohistochemistry deparaffinized sections were incubated with 0.1% testicular hyaluronidase (Sigma) for 30 min at 37ºC to remove potentially masking GAG residues. Sections selected for hyaluronan localization were omitted from this pretreatment with the exception of samples used as controls to test efficacy of hyaluronidase digest. Subsequent immunohistochemical staining procedures were a modification of Capehart et al 3. Briefly, sections were blocked with PBS containing 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 1% normal goat serum (NGS) for 1 hr and incubated with primary immunoreagents overnight at 4ºC. Sections were then washed with PBS and incubated with fluorescein or rhodamine-conjugated anti-mouse or –rabbit IgG secondary antibodies (ICN-Cappel) diluted 1:200 in blocking buffer for 2 hours at room temperature. Sections selected for hyaluronan staining were treated with FITC-strepavidin (Vector Labs). Primary antibodies were omitted from control specimens. Sections were washed with PBS, post-fixed in 80% and 50% ethanols, re-equilibriated in PBS, and mounted in 10% PBS-90% glycerol containing 100mg/mL 1,4-diazabicyclo(2,2,2)octane (Sigma). Slides were viewed with an Olympus BX-40 equipped with epifluorescence optics and images captured using a SPOT-RT camera and software.

3. Results and Discussion

The current study was conducted in order to determine if the pattern of versican expression was conserved and consistent with a role for this molecule during synovial joint development in the avian limb. To establish the temporal and spatial expression of versican and aggrecan proteoglycans relative to overt chondrogenesis and joint morphogenesis we employed immunohistochemical analysis of limb sections from paraffin-embedded wild-type chick embryos during time periods critical to elbow joint morphogenesis (HH st25–41).

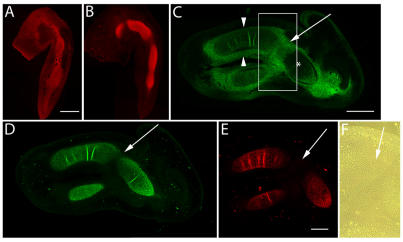

Previous studies have shown that at HH st20 versican is expressed evenly throughout the limb bud 24, however, by HH st25, as noted previously, versican expression was restricted to the chondrogenic mesenchyme in the older, more proximal areas (Fig. 1A). HH st25 also marks the onset of aggrecan expression in the chick limb 22 and the beginnings of elbow joint interzone formation (Fig. 1A,B). Interzone formation is required for joint morphogenesis 13, and consistent with the cell flattening observed during this process, ectopic expression of a “miniversican” gene construct (consisting of a complete G1 domain, a partial CS domain, and complete G3 domain) was demonstrated to promote chondrocyte elongation in vitro 33. Expression of versican and aggrecan initially overlapped in the incipient cartilage model, however, aggrecan expression was reduced in the presumptive joint interzone and absent from the undifferentiated distal limb mesenchyme. At HH st28, versican expression began to be lost from the limb cartilage core (Fig. 1C,F), yet was still expressed at high levels in the fibroblast-like cells of the perichondrium and joint interzone. At this stage, aggrecan expression further diminished in the flattened cells of the developing joint (Fig. 1D) and co-distributed with the type II collagen positive cartilage matrix for the remaining stages examined (Fig. 1E).

Figure 1.

Immunolocalization of versican in relation to chondrogenic tissue in the developing chick limb. A,B are sections through the chick wing at HH st25, and C-F at HH st28 of development. A,B: Versican (A) and aggrecan (B) expression (red) initially overlap in much of the early chondrogenic limb core, however, aggrecan is absent from presumptive joint forming regions and versican expression is also localized in the distal limb mesenchyme. C: Versican (green) is beginning to disappear from the newly differentiated humeral chondrocytes (asterisk), yet strong versican expression is maintained in the joint interzone (arrow) and perichondrium (arrowheads). D,E: Aggrecan (D) and type II collagen (E) expression are strongly localized in incipient cartilages but largely absent from the joint interzone (arrows). F: Phase micrograph of boxed area in panel C showing versican positive interzone cells. Scale bar = 250µm (A,B); 500µm (C,D); 500µm (E,F).

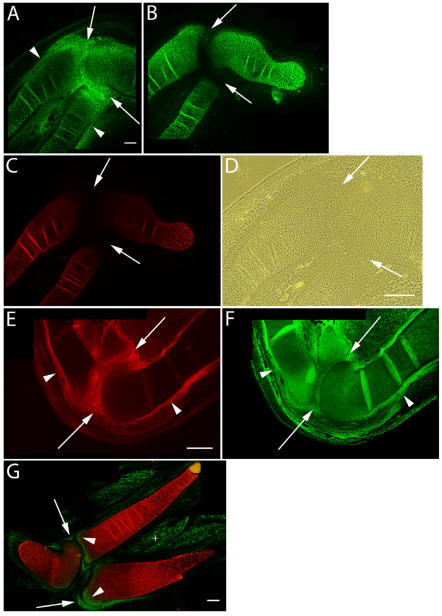

Versican expression in the elbow region of HH st34-36 limb sections was again largely localized in areas where cell shape is more flattened (Fig. 2A,D). These areas included the epiphyseal ends of the radial, ulnar, and humeral cartilages and surrounding perichondrium. In contrast, aggrecan and Type II collagen expression were restricted to rounded chondrogenic cells of the cartilage during the intermediate stages of joint formation (Fig. 2B,C). The onset of cavitation coincides with increased hyaluronan synthesis and up-regulation of CD44 expression by interzone cells 1, 5, 21. The N-terminal G1 globular domain of versican specifically binds hyaluronan 7, 15, 19 and it is of particular interest to note that hyaluronan binding proteins present in the joint interzone have been suggested to aid in separation events 6. Consistent with these findings, we immunolocalized strong expression of versican proteoglycan (Fig. 2E) and hyaluronan (Fig. 2F) in the joint interzone and immediate surrounding area just prior to cavitation. HH st36 marks onset of cavitation and by this stage versican expression was reduced to background levels in all but the epiphyseal ends of the cartilage template of adjacent skeletal elements comprising the elbow and future articular surfaces (Fig. 2G). At this stage, versican was also expressed by a population of periarticular cells at the periphery of the forming joint cavity.

Figure 2.

Immunolocalization of versican in relation to chondrogenic tissue in the developing chick limb. A-D are sections through the chick wing at HH st34 of development, E,F at HH st35 and G at HH st36 double labeled with versican (green) and type II collagen (red). A: Versican expression is reduced in the chondrogenic rod, but is maintained at high levels in the perichondrium (arrowheads) and joint interzone (arrows). B,C: Aggrecan (B) and type II collagen (C) are highly expressed by differentiated chondrocytes but are absent from the perichondrium and joint interzone (arrows). D: Phase micrograph of limb section in A showing cells of the joint interzone that express high levels of versican proteoglycan. E,F: Versican (E) and hyaluronan (F) expression overlap in the perichondrium (arrowheads) and joint interzone (arrows). Hyaluronan expression was widespread in limb tissues. G: Versican expression (green) is now largely absent from type II collagen (red) positive matrix, and is strongly expressed by periarticular cells bordering the joint space (arrows) and at the epiphyseal ends of the radius and ulnar olecranon process (arrowheads). Versican expression is also detected in the endomysium surrounding individual muscle fibers (+). Scale bars = 250µm (A-C); 250µm (D); 250µm (E,F); 250µm (G).

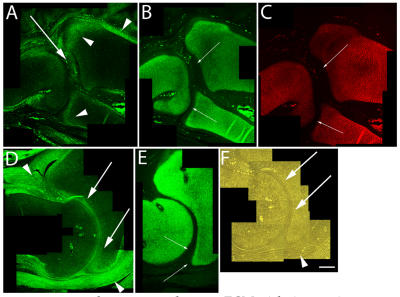

Articular cartilage is traditionally thought to simply be the remaining cartilage from the embryonic epiphyses that is never replaced by bone. This concept is, however, challenged by the hypothesis that articular cartilage arises from a distinct population of cells. Regardless of origin, permanent maintenance of the stable articular chondrocyte phenotype is crucial to joint function. By HH st38-41 cavitation of the elbow joint is readily evident, and although high levels of versican expression were found in the perichondrium and surrounding joint capsule, the data presented herein show that between HH st38-41 versican in the cartilaginous skeleton became more localized along the future articular surfaces of the radial, ulnar and humeral cartilages (Fig. 3A,D,F). In contrast, aggrecan (Fig. 3B,E) and type II collagen (Fig. 3C) were localized in a predominately non-overlapping region of underlying epiphyseal chondrogenic cells and matrix.

Figure 3.

Immunolocalization of versican in relation to chondrogenic tissue in the developing chick limb. A,B,C are sections through the chick wing at HH st38 and D,E,F at HH st41 of development. A,D: Versican continues to localize along the joint interzone (arrows) and in the immediate surrounding area (arrowheads). Note progressive loss of versican in most of the maturing epiphysis but continued expression along articular surfaces of the developing elbow in D. B,C,E: As seen at earlier stages, strong aggrecan (B,E) and type II collagen (C) expression remain in all areas of the cartilage anlagen except for those versican positive regions along the developing articulation (small arrows). F: Phase micrograph of D, showing articular chondrocytes (arrows) as the likely source of versican expression (arrowhead denotes forming joint capsule). Scale bar = 250µm for all panels.

These findings are in agreement with preliminary studies of versican localization in presumptive joint regions in mouse 25, 30 and further support a conserved role for this molecule during chondrogenesis and synovial joint morphogenesis in both avian and murine models.

4. Conclusion

Development of synovial joints has been shown to be a complex process involving cell flattening, and cavitation, mediated in part by accumulation of hyaluronan GAG 5, all of which occur in the interzone. Surprisingly, despite an extensive number of morphological studies describing joint development and its clinical importance relative to degenerative diseases, the role many ECM molecules have during the growth and differentiation of synovial joints is far from understood.

Extracellular matrices rich in versican and hyaluronan provide a highly hydrated environment that promotes the cell proliferation and migration, and the versican-HA complexes surrounding cells serve an important role in controlling cell shape and cell division 17, 27. Furthermore, it has been hypothesized that versican must be downregulated before terminal chondrocyte differentiation can occur 32. Consistent with these studies, our data show that versican was strongly expressed by flattened fibroblast-like cells of the joint interzone and surrounding perichondrium. This pattern of expression was maintained throughout the time period encompassing interzone formation until cavitation of the elbow joint. At this latter stage versican expression by articular chondrocytes continued at the epiphysis. Aggrecan on the other hand was shown to be exclusively localized in overt cartilage matrix and was absent from both the perichondrium and joint interzone after their first morphological appearance in the limb. Furthermore, as demonstrated here, expression of versican was in a largely non-overlapping pattern with aggrecan at the developing articulation suggesting that the cells of the forming articular cap possess different properties from the adjacent chondrocytes. This pattern of aggrecan localization co-distributed with type II collagen expression and remained constant in cartilages around the forming joint at all stages examined. The present report provides the first detailed analysis of versican localization during avian joint morphogenesis and results suggest that an ECM rich in versican may facilitate creation of an environment that promotes maintenance of the flattened fibroblast-like cell morphology within the interzone and may function in formation or organization of the articular surface.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by NIH HD040846-02A1.

References

- 1.Archer CW, Morrison H, Pitsillides AA. Cellular aspects of the development of diarthrodial joints and articular cartilage. J Anat. 1994;184:447–456. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brunet LJ, McMahon JA, McMahon AP et al. Noggin, cartilage morphogenesis and joint formation in the mammalian skeleton. Science. 1998;280:1455–7. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5368.1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Capehart AA, Mjaatvedt CH, Hoffman S et al. Dynamic expression of a native chondroitin sulfate epitope reveals microheterogeneity of extracellular matrix organization in the embryonic chick heart. Anat Rec. 1999;254:181–195. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(19990201)254:2<181::AID-AR4>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Craig FM, Bentley G, Archer CW. The spatial and temporal pattern of collagens I and II and keratan sulphate in the developing chick metatarsophalangeal joint. Development. 1987;99:383–91. doi: 10.1242/dev.99.3.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Craig FM, Bayliss MT, Bentley G et al. A role for hyaluronan in joint development. J Anat. 1990;171:17–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Downwaite GP, Edwards JCW, Pitsillides AA. An essential role for the interaction between hyaluronan and hyaluronan binding proteins during joint development. J Histochem Cytochem. 1998;46:641–651. doi: 10.1177/002215549804600509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evanko SP, Angello JC, Wight TN. Formation of hyaluronan and versican-rich pericellular matrix is required for proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:1004–1013. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.4.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferrari D, Kosher RA. Expression of Dlx5 and Dlx6 during specification of the elbow joint. Int J Dev Biol. 2006;50:709–713. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.062180df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Francis-West PH, Parish J, Lee K et al. BMP/GDF-signaling interactions during synovial joint development. Cell Tissue Res. 1999;296:111–119. doi: 10.1007/s004410051272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hall BK, Miyake T. The membranous skeleton: the role of cell condensations in vertebrate skeletogenesis. Anat Embryol. 1992;186:107–124. doi: 10.1007/BF00174948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamburger V, Hamilton H. A series of normal stages in the development of the chick embryo. J Morph. 1951;188:49–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hartmann C, Tabin CJ. Wnt-14 plays a pivotal role in inducing synovial joint formation in the developing appendicular skeleton. Cell. 2001;104:341–51. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00222-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holder N. An experimental investigation into the early development of the chick elbow joint. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1977;39:115–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iwamoto M, Higuchi Y, Koyama E et al. Transcription factor ERG varients and functional diversification of chondrocytes during limb long bone development. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:27–40. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawashima H, Hirose M, Hirose J et al. Binding of a large chondroitin sulfate/dermatan sulfate proteoglycan, versican, to L-selectin, P-selectin, and CD44. J Biol Chem. 2000;45:35448–35456. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003387200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kimata K, Oike Y, Tani K et al. A large chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan (PG-M) synthesized before chondrogenesis in the limb bud of chick embryo. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:13517–13525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee GM, Johnstone B, Jacobson K et al. The dynamic structure of the pericellular matrix on living cells. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:1899–907. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.6.1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lizarraga G, Lichtler A, Upholt WB et al. Studies on the role of Cux1 in regulation of the onset of joint formation in the developing limb. Dev Biol. 2002;242:44–54. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsumoto K, Shionyu M, Go M et al. Distinct interaction of versican/PG-M with hyaluronan and link protein. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:41205–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305060200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitrovic D. Development of the diarthrodial joints in the rat embryo. Am J Anat. 1978;151:475–85. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001510403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pitsillides AA, Archer CW, Prehm P et al. Alterations in hyaluronan synthesis during developing joint cavitation. J Histochem Cytochem. 1995;43:263–273. doi: 10.1177/43.3.7868856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwartz NB, Hennig AK, Krueger RC, et al. Developmental expression of S103L crossreacting proteoglycans in embryonic chick. In: Fallon JF, Goetinck PF, Kelley RO, Stocum DL, editors. Limb development and regeneration. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1993. pp. 505–514. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shibata S, Fukada K, Imai H et al. In situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry of versican, aggrecan, and link protein, and histochemistry of hyaluronan in the developing mouse limb bud cartilage. J Anat. 2003;203:425–432. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2003.00226.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shinomura T, Jensen KL, Yamagata M et al. The distribution of mesenchyme proteoglycan (PG-M) during wing bud outgrowth. Anat Embryol. 1990;181:227–233. doi: 10.1007/BF00174617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Snow HE, Riccio LM, Hoffman S et al. Versican expression during skeletal/joint morphogenesis and patterning of muscle and nerve in the embryonic mouse limb. Anat Rec. 2005;282:95–105. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.20151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Storm EE, Kinglsey DM. Joint patterning defects caused by single and double mutations in members of the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) family. Development. 1996;122:3969–79. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.12.3969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wight TN. Versican: a versatile extracellular matrix proteoglycan in cell biology. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14:617–23. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00375-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamagata M, Shinomura T, Kimata K. Tissue variation of two large chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (PG-M/versican and PG-H/aggrecan) in chick embryos. Anat Embryol. 1993;187:433–44. doi: 10.1007/BF00174419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamagata M, Kimata K. Repression of a malignant cell-substratum adhesion phenotype by inhibiting the production of the anti-adhesive proteoglycan, PG-M/versican. J Cell Sci. 1994;107:2581–90. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.9.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamamura H, Zhang M, Markwald RR et al. A heart segmental defect in the anterior-posterior axis of a transgenic mutant mouse. Dev Biol. 1997;186:58–72. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zanin MK, Bundy J, Ernst H et al. Distinct spatial and temporal distributions of aggrecan and versican in the embryonic chick heart. Anat Rec. 1999;256:366–380. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(19991201)256:4<366::AID-AR4>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Y, Cao L, Kiani CG et al. The G3 domain of versican inhibits mesenchymal chondrogenesis via the epidermal growth factor-like motifs. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:33054–33063. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.33054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Y, Wu Y, Cao L et al. Versican modulates embryonic chondrocyte morphology via the epidermal growth factor-like motifs in G3. Exp Cell Res. 2001;263:33–42. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.5095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zimmermann DR, Ruoslahti E. Multiple domains of the large fibroblast proteoglycan, versican. EMBO J. 1989;8:2975–2981. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08447.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]