Abstract

The importance of protein glycosylation in the interaction of pathogenic bacteria with their host is becoming increasingly clear. Neisseria meningitidis, the etiological agent of cerebrospinal meningitis, crosses cellular barriers after adhering to host cells through type IV pili. Pilin glycosylation genes (pgl) are responsible for the glycosylation of PilE, the major subunit of type IV pili, with the 2,4-diacetamido-2,4,6-trideoxyhexose residue. Nearly half of the clinical isolates, however, display an insertion in the pglBCD operon, which is anticipated to lead to a different, unidentified glycosylation. Here the structure of pilin glycosylation was determined in such a strain by “top-down” MS approaches. MALDI-TOF, nanoelectrospray ionization Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance, and nanoelectrospray ionization quadrupole TOF MS analysis of purified pili preparations originating from N. meningitidis strains, either wild type or deficient for pilin glycosylation, revealed a glycan mass inconsistent with 2,4-diacetamido-2,4,6-trideoxyhexose or any sugar in the databases. This unusual modification was determined by in-source dissociation of the sugar from the protein followed by tandem MS analysis with collision-induced fragmentation to be a hexose modified with a glyceramido and an acetamido group. We further show genetically that the nature of the sugar present on the pilin is determined by the carboxyl-terminal region of the pglB gene modified by the insertion in the pglBCD locus. We thus report a previously undiscovered monosaccharide involved in posttranslational modification of type IV pilin subunits by a MS-based approach and determine the molecular basis of its biosynthesis.

Keywords: mass spectrometry, pglB, Pili

In eukaryotes, glycosylation is recognized as a key feature of surface proteins involved in particular in cell–cell and cell–matrix recognition. Recently, an increasing number of reports describe O- and N-glycosylation of surface bacterial proteins, in particular in mucosa-associated pathogens (1). The importance of these glycosylation events in host colonization and pathogenesis is becoming increasingly clear.

The Gram-negative bacterium Neisseria meningitidis is a commensal of the human nasopharynx: 10–20% of the human population are carriers (2). N. meningitidis is, however, better known as the etiologic agent of cerebrospinal meningitis. At a low frequency, the bacteria cross the epithelial barrier and access the bloodstream where they rapidly proliferate, causing septicemia. In the bloodstream, N. meningitidis interacts with endothelial cells, crosses the blood–brain barrier, and proliferates in the brain.

Bacterial adhesion is a crucial step to colonize the nasopharynx and is thought to be a prerequisite for crossing the epithelium, accessing the blood, and crossing the blood–brain barrier (3, 4). Like numerous pathogens such as enteropathogenic Escherichia coli, Vibrio cholerae, or Pseudomonas aeruginosa, pathogenic Neisseria harbor type IV pili that allow efficient colonization of the human mucosa (5). Although 15 proteins are involved in type IV pili biogenesis in N. meningitidis (6), the main component of this filamentous organelle is the pilin protein encoded by the pilE gene.

PilE undergoes several posttranslational modifications including glycosylation, although the role of these modifications remains unclear. Pilin glycosylation in Neisseria gonorrhoeae MS11 strain was first described based on crystallographic data (7) as an O-linked disaccharidic glycosylation of serine-63. In the N. meningitidis C311 strain, a trisaccharide composed of Gal(β1–4) Gal(α1–3) 2,4-diacetamido-2,4,6-trideoxyhexose (DATDH) was identified by using GC-MS (8). A similar structure was found on the pilin of the MS11-derived N400 strain by using MS approaches (9, 10) with a hexose linked to a DATDH.

The genes involved in pilin glycosylation, designated as pgl genes for pilin glycosylation, were initially identified based on sequence homology searches. The pglA gene was first identified (11), followed by the pglBCD cluster (12, 13). The individual function of N. meningitidis PglB, PglC, and PglD was proposed by Power et al. (12) based on sequence homologies of the pgl genes from the MC58 and C311 N. meningitidis strains, which present a DATDH on serine-63. Based on these predictions, these enzymes would synthesize UDP-DATDH from UDP-GlcNAc with steps of dehydration (PglD) on carbons 4 and 6, and an amino transfer (PglC) and acetylation (PglB) on carbon 4. Homologs of the pglBCD genes can be found in Campylobacter jejuni, which synthesizes 2,4-diacetamido-2,4,6-trideoxyglucopyranose as part of an oligosaccharide present on several proteins (14–16). The individual function of the proteins encoded by the C. jejuni pgl genes has been characterized at the biochemical level, and these results confirm the predicted functions for the pglBCD genes in N. meningitidis (17, 18). PglB is a bifunctional enzyme, the carboxyl-terminal half (PglBCter) has the acetylation activity described above, and the amino-terminal half transfers the activated DATDH to a lipid carrier. Galactose residues are added to DATDH by pglA and pglE (19). The glycolipid would be transported to the periplasmic side of the inner membrane by PglF, and, finally, PglL would transfer the oligosaccharide to PilE (20).

Importantly, Kahler et al. (13) reported a variation on this theme; in their N. meningitidis strain (NMB), an insertion was found in the pglB gene. As a consequence, the carboxyl-terminal part of PglB does not present any homology to acetyl transferases but rather with carbamoyl phosphate synthase. This new allele was called pglB2. It was speculated that this new gene arrangement would lead to a different pilin glycosylation. Jennings and colleagues (19) later screened a collection of 42 clinical N. meningitis isolates for the presence of the pglB2 allele and ORF8 to find that 48% of the strains displayed the insertion, including the sequenced strain FAM18. Interestingly, the presence of sequence homologous to pglB downstream of the pglB2-ORF8 insertion in both NMB and FAM18 strains suggests that the pglB allele existed before the pglB2 allele (19).

Because half of the clinical isolates display the pglB2 allele we characterized the nature of the saccharide present on type IV pili in such a strain using a combination of “top-down” MS approaches. Top-down approaches have been shown to be of great value for analysis of posttranslational modifications (21, 22), including for pilin glycosylation (9). We designed a strategy based on collision-generated sugar fragmentation to gain insight in the sugar structure. Pilin glycosylation was found to be a previously unknown hexose containing a glyceramido group. We further show that the presence of the carboxyl-terminal region of the PglB protein determines the presence of this novel sugar on type IV pilin subunits.

Results

The N. meningitidis 8013 Strain Displays an Alternative Pilin Subunit Glycosylation.

The genomic sequence of the 8013 N. meningitidis strain revealed that it displays the pglB2 allele of the pglB gene (V.P., unpublished data). Pili were partially purified from the wild-type 8013 strain as well as from mutant strains, and crude preparations were examined by MALDI-TOF MS. Pili purified from the wild-type strain produced one main peak at a mass of 17,495 Da along with peaks of lower intensity at 17,653 Da and 17,698 Da [supporting information (SI) Fig. 5]. Repeated measurements of different pili preparations (n = 10) provided an average mass of 17,496 Da for the main peak with a standard deviation of 5 Da.

To specifically determine the mass of the sugar present on amino acid 63 of the pilin subunit, pili were purified from a strain expressing the PilE protein with a point mutation substituting serine-63 for an alanine (S63A, green). The MALDI-TOF analysis demonstrated that the average molecular mass of the pilin expressed by the pilES63A mutant is 17,209 ± 11 Da (n = 4). Taking into account the serine-to-alanine mutation (−16 Da), the mass of the posttranslational modification on serine-63 corresponded to an approximate mass shift of 271 Da. This did not correspond to the expected mass for DATDH (228 Da), Hexose-DATDH, or any of posttranslational modification present in public databases (RESID, UNIMOD, and Delta Mass) indicating the presence of an unidentified sugar residue (23).

We then checked whether the enzymes encoded by the pgl genes were involved in the biosynthesis of the unknown modification found in the 8013 strain. The gene encoding the PglA glycosyltransferase is in the off phase in the 8013 strain (V.P., unpublished data), and, consistently, pilin purified from a strain containing a transposon insertion in the pglA gene revealed a mass of 17,497 ± 11 Da (n = 4), not significantly different from the mass of the wild-type pilin, suggesting that PilE from the 8013 strain is modified with a monosaccharide. PilE protein purified from pglB, pglC, and pglD strains exhibited similar masses with 17,231 ± 6 (n = 3), 17,235 ± 2 (n = 3), and 17,226 ± 7 Da (n = 6), respectively. When compared with the wild-type strain, this indicated approximate mass shifts of 265 Da, 261 Da, and 270 Da for pglB, pglC, and pglD mutants respectively. PglB, PglC, and PglD are therefore necessary for the glycosylation of PilE, suggesting that it corresponds to a saccharidic structure similar to DATDH. Consistent with a previous report (13), a transposon insertion in the HAD-like gene (24) immediately downstream of pglB did not affect pilin glycosylation (data not shown). Overall, this whole-protein MALDI-TOF analysis of the posttranslational modification of serine-63 pointed to a single saccharidic residue similar to but distinct from DATDH with an approximate mass of 270 Da.

Determination of the Mass of Pilin Glycosylation by Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance (FT-ICR).

FT-ICR MS can achieve mass measurement accuracy of ≤10 ppm, corresponding to a 0.18-Da standard deviation for 18-kDa proteins. Samples were therefore analyzed by a 7-T FT-ICR equipped with nanoelectrospray. Masses will be given as the calculated monoisotopic mass value followed by the mass difference (in units of 1.00235 Da) between the most abundant isotopic peak and the monoisotopic peak (in italics).

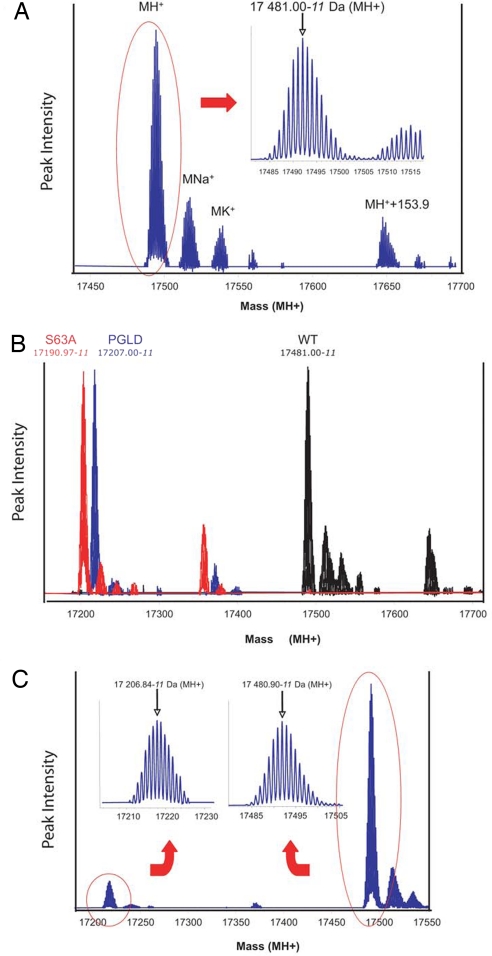

PilE yielded a main peak at 17,481.00-11 Da (MH+) after deconvolution. Enlargement of the corresponding mass range shows a completely resolved isotopic pattern (Fig. 1A). Satellite peaks corresponding to sodium (M+Na+) and potassium (M+K+) adducts are also present, as is frequently observed for protein analysis. A secondary peak (MH+ +153.93) is also found, probably corresponding to an addition of one phosphoglycerol (+154.00 Da theoretically) compared with the PilE main peak as previously observed (25).

Fig. 1.

FT-ICR analysis of PilE glycosylation. (A) Analysis of pili purified from the wild-type strain. An enlargement of the spectrum in the mass range of 17,480–17,520 Da showing a resolved isotopic envelope for the MH+ ion is depicted in Inset. (B) Analysis of the nonglycosylated forms of PilE. Pili from the pilES63A strain (red) and the pglD strain (blue) were compared with wild type (black). (C) PilE molecules subjected to ISD lose their sugar moiety, leading to the appearance of a secondary peak corresponding to the mass of the pilin without the sugar.

Pilin subunits purified from the pglD and pilES63A strains yielded masses of 17,207.00-11 Da and 17,190.97-11, respectively (Fig. 1B). Taking into account the serine-to-alanine mutation (Δmass = 15.99 Da), the pilES63A mutant indicated a modification with a mass of 274.04 Da (17,481.00–17,190.97–15.99). Accordingly, the pglD mutation led to a 274.00-Da mass shift (17,481.00–17,207.00). FT-ICR MS also allowed in-source dissociation (ISD) of the sugar residue, allowing measurement of the mass of the protein without its sugar moiety. In these conditions a new peak appeared in the spectrum corresponding to the loss of 274.06 Da (17,480.90–17,206.84) (Fig. 1C). As a comparison, pili were purified from a pglA mutant of the MS11 N. gonorrhoeae strain and subjected to the same experimental procedure. As expected, ISD led to the loss of 228.1 Da from the entire protein (data not shown), which corresponds to DATDH (10).

These results indicated without ambiguity that serine-63 of PilE of N. meningitidis strain 8013 carries a sugar, which in its free form is 292 Da in mass (274 + 18). To our knowledge, this mass has never been described before.

Collision-Induced Sugar Fragmentation Using Quadrupole TOF (Q-TOF) MS Reveals Atypical Glyceramido Hexose.

Because we have shown above that it was possible to detach the sugar from the protein by ISD, we sought to observe the oxonium ion of the sugar and fragment it to get insight into its structure (26, 27). This was done by using a Q-TOF Premier (Waters, Milford, MA) mass spectrometer, which allows both mass accuracy and efficient fragmentation for low mass ions.

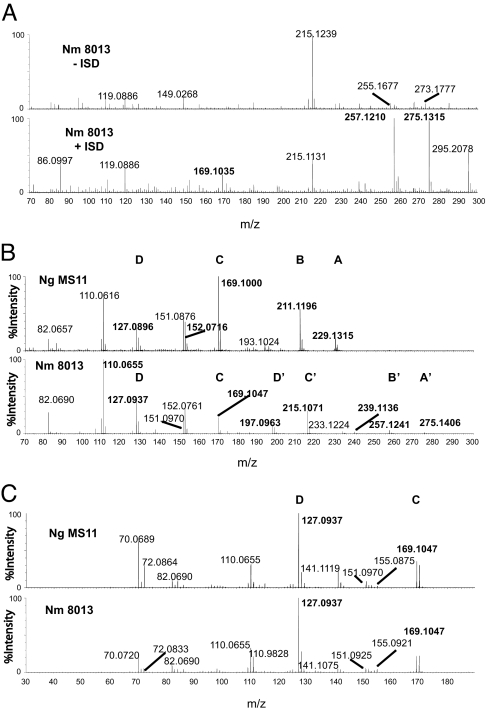

ISD from the wild-type pili sample of N. meningitidis led to the formation of an ion at m/z 275.13 (absent at 40 V), corresponding to the expected oxonium species (Fig. 2A, compare Upper and Lower). This ion was accompanied by satellite ions at m/z 257.12 (compatible with a loss of water) and m/z 169.10. ISD treatment on pilin from the N. gonorrhoeae MS11 strain led to the apparition of ions at m/z 229.12, 211.11, and 169.10 (data not shown). m/z 229.12 corresponded to the expected oxonium ion of DADTH, and m/z 211.11 corresponded to its dehydrated product. m/z 169.10 is a fragment common to both sugars, suggesting that they had related structures.

Fig. 2.

Determination of glycan structure by ISD and MS/MS. Crude pili preparations were analyzed with a Q-TOF Premier instrument. Samples were submitted to ISD to cleave the sugar from the rest of the protein and to form the corresponding oxonium ions. Ions were then analyzed by a quadrupole mass spectrometer, and chosen ions were further fragmented by collision and analyzed by TOF mass spectrometry. (A) Comparison of the ion profile in the presence (+ISD) and the absence (−ISD) of ISD. Ions of interest are indicated in bold. (B) Fragmentation of monosaccharides dissociated from PilE purified from the N. gonorrhoeae MS11 strain (Ng MS11, m/z 229.1 Da) and the N. meningitidis 8013 strain (Nm 8013, m/z 275.1 Da) by ISD. (C) Fragmentation of the 169.1-Da ion from both sugars.

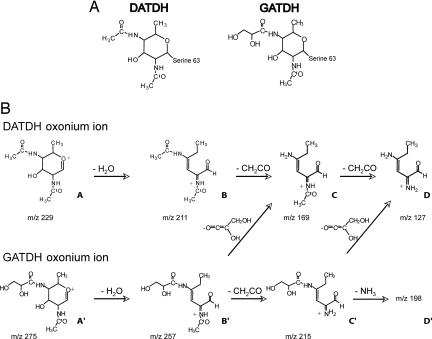

In the second step of the analysis, tandem MS (MS/MS) experiments on ions of interest were performed. MS/MS of ion m/z 229.12 corresponding to the DATDH oxonium ion from the N. gonorrhoeae strain is shown in Fig. 2B Upper, ion A. The proposed structures of most of the observed ions are presented in Fig. 3. The main fragmentation is the loss of 18.01 Da, which corresponds to a molecule of water (H2O) leading to an ion at m/z 211.1. This water loss is commonly observed for oxonium ions but has never been rationalized. Different pathways are proposed in SI Fig. 6 to account for this water loss. From m/z 211, a molecule of ketene (CH2CO, theoretical mass 42.00 Da) can be lost from one acetamido group to give m/z 169.1 Da. SI Fig. 7 shows different isomeric structures for m/z 169.1, depending on which acetamido group is reacting first. Note that m/z 169.1 can further lose NH3 to form a m/z 152.1 ion. A second loss of ketene (from the second acetamido group) is also observed from m/z 169.1 to give m/z 127. These losses of ketene are very facile for protonated acetamido groups. The mechanism for this elimination is depicted in SI Fig. 7.

Fig. 3.

Structures and fragmentation patterns of DATDH and GATDH. (A) Structures of DATDH and GATDH linked to serine-63 of PilE. (B) Proposed successive steps of fragmentation of DATDH and GATDH.

MS/MS of the unknown ion m/z 275.13 is shown in Fig. 2B Lower. Comparison with MS/MS of oxonium ion of DADTH (m/z 229.12) (Fig. 2B Upper) revealed a similar spectrum (nearly identical, in the range of 70–170 m/z), which confirmed a common core for both sugars. The loss of one molecule of water from m/z 275.1 leads to the formation of m/z 257.1, arguing for the presence of at least one hydroxyl group on the structure (Fig. 3). A second loss of water is also observed (m/z 239.1), probably indicative of a second hydroxyl group, absent for N. gonorrhoeae. As for DATDH, the dehydrated oxonium ion can further lose a ketene group (followed by a NH3 elimination) to give ions m/z 215.1 and m/z 198.1. This clearly demonstrates the presence of one acetamido group in the unknown sugar.

Another important fragmentation for m/z 275.1 is the formation of ions at m/z 169.1 as is found for the DATDH structure. MS/MS analyses of m/z 169.1 ions formed (i) from ISD of type IV pili of N. gonorrhoeae and (ii) from ISD of type IV pili of N. meningitidis were undertaken. Results show that both ions yield identical MS/MS spectra, which means that their structure is identical (Fig. 2C). The main fragmentation is, again, the loss of 42.01 Da followed by a loss of NH3 (to give m/z 110.06), which indicates that m/z 169.1 also contains one acetamido group.

Taken together, these results show that the unknown sugar contains one acetamido group and at least two hydroxyl functions and fragments easily to give an ion at m/z 169.1, which also contains an acetamido group. The structure of this m/z 169.1 ion is the same as the one depicted in Fig. 3B for DATDH. Thus, the only difference between DATDH and the unknown sugar is that one acetamido group has been replaced by an 89-Da group (257–169 + 1) containing at least one hydroxyl. Only a 2,3-dihydroxypropanamido (also called glyceramido) group fits this description (Fig. 3A). The fragmentation sequence is proposed in Fig. 3B. Accordingly, switching the acetyl group for a glyceramido group accounts for the 46.01-Da difference measured between both glycans. The elemental composition of this new sugar is C11N2O7H20 (in its free form), which corresponds to a molecular mass of 292.13 Da, consistent with the above results comparing the masses of pilin with and without sugar.

These MS data demonstrate that the sugar present on serine-63 of N. meningitidis 8013 strain is a 2-acetamido 4-glyceramido 2,4,6-trideoxyhexose or 2-glyceramido 4-acetamido 2,4,6-trideoxyhexose depending on the relative positions of the glyceramido and the acetamido groups. For the remainder of the study the sugar will be referred to as a glyceramido acetamido trideoxyhexose (GATDH).

The pglB2 Allele Determines the Synthesis and Subsequent Transfer of GATDH on Pilin Subunits.

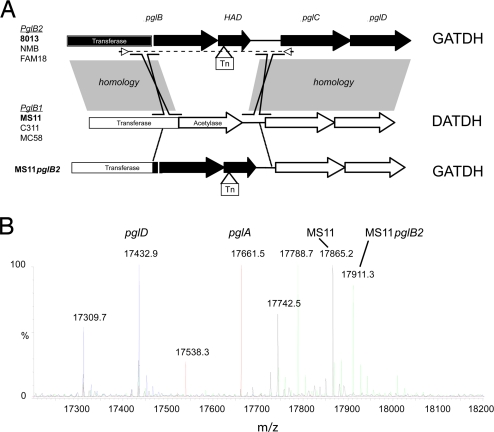

The above results demonstrate that the 8013 strain expresses a previously unidentified hexose containing a glyceramido group, which differs from the DATDH residue previously described. It was tempting to explain this difference by the expression of a pglB2 allele by the 8013 strain for the following reasons: (i) the difference between the two sugars is the presence of a glyceramido instead of an acetyl group of the hexose; (ii) in strains expressing the DATDH-modified pilin, the acetyl group of DATDH is transferred to the C4 of the hexose by the carboxyl terminus of the pglB gene; and (iii) the pglB2 allele is characterized by a different carboxyl-terminal portion of PglB, generating a protein with unknown function (Fig. 4). To demonstrate that the carboxyl-terminal region of PglB is responsible for the synthesis of GATDH rather than DATDH, the pglB1 allele from the N. gonorrhoeae MS11 strain was replaced by the pglB2 allele from the N. meningitidis 8013 strain, generating the MS11pglB2 strain (see Materials and Methods).

Fig. 4.

The pglB allele determines whether DATDH or GATDH is transferred to PilE serine-63. (A) Genetic organization of the pglB1 and pglB2 alleles from different Neisseria spp. strains. The gray shaded area indicates regions of homology between both strains. Arrows and the dotted line indicate the region amplified by PCR to insert the pglB2 allele into the pglB1-expressing MS11 strain. Tn indicates a transposon insertion site. (B) Q-TOF analysis of MS11 pilin glycosylation. Pili were purified from the MS11 strain (MS11), a pglA mutant strain (pglA), a pglD mutant strain (pglD), and the MS11 strain expressing the pglB2 allele (MS11pglB2).

Pili were purified from the MS11pglB2 strain, and whole pilin subunits were analyzed by nanoelectrospray ionization Q-TOF (Fig. 4, MS11pglB2). Our objective was to use MS to detect the presence or absence of DATDH or GATDH in these pili subunits. For that purpose, these experiments were undertaken on the Q-TOF instrument, which provides accurate average mass measurements and high sensitivity. Pili were also purified from the MS11 strain (MS11), a pglA mutant (pglA), and a pglD mutant (pglD). MS analysis of pilin purified from the MS11 strain yielded two main peaks after deconvolution in neutral molecular masses of the multicharged ion spectrum: one peak corresponding to a molecular mass of 17,865.2 Da and another at 17,742.5 Da. The 122-Da difference between the two masses corresponds to the previously described phosphoethanolamine residue present on only a portion of the PilE protein in the MS11 strain (9). As expected, the pglA mutant, which lacks N-acetylhexosamine (203 Da), yielded a mass of 17,661.5 Da, and the pglD mutant, which lacks both N-acetylhexosamine and DATDH (228 Da), gave a molecular mass of 17,432.9 Da. Finally, when the pglB2 allele originating from the 8013 strain was transferred to the MS11 strain (Fig. 4, MS11pglB2), the whole pilin mass was shifted to 17,911.3 Da, which corresponds to the pilin mass (17,432.9 Da) with one N-acetylhexosamine (203 Da) and one GATDH (274.1 Da). In conclusion, the nature of the pglB allele determines the modification present on the hexose and thus the nature of the sugar. If it is a pglB1 allele pilin will be modified with a DATDH, and if it is a pglB2 allele it will be a GATDH.

Discussion

Although the importance of protein glycosylation was first recognized in eukaryotes, it has become increasingly clear that numerous bacterial proteins are posttranslationally modified by glycosylation and that these modifications are key in various biological and pathological processes (1). The nature of pilin glycosylation of the N. meningitidis 8013 clinical isolate was determined in this report. A top-down approach by MS was selected because it gives a more global and quantitative view of posttranslational modifications. MALDI-TOF allowed rapid screening of a large number of mutants and determination of an approximate mass with a standard deviation of ≈5 Da for the 18-kDa pilin. FT-ICR allowed precise measurement of the modification even on the whole protein with a standard deviation of <0.2 Da. FT-ICR also allowed the sugar moiety to dissociate by ISD, thus determining sugar mass from only one protein sample and by analysis of a single spectrum. We then exploited the possibility to cleave the sugar moiety by ISD to run a sample on a MS/MS Q-TOF. Monosaccharidic modifications of proteins are generally difficult to analyze because it is technically challenging to chemically separate the monosaccharide from the protein backbone. In addition, sugar structure analysis is generally based on GC, which relies on large amounts of highly purified and derivatized starting material. The successive combination of ISD followed by MS/MS allowed analysis of the sugar structure starting from small amounts of a partially purified protein. Our approach therefore combined sensitivity, speed, and precision. Furthermore, this approach should be applicable to different glycosylated proteins and should therefore be of general value. The sugar present on the N. meningitidis 8013 strain was found to be closely related to DATDH previously identified on neisserial pilin subunits. The 46-Da difference between both sugars was localized on one of the two carbons bearing an acetamido group. Instead of two acetamido groups in the C2 and C4 positions, the sugar of the 8013 strain carries one acetamido and one glyceramido group, making it a GATDH. The relative position of the glyceramido and acetamido groups on the C2 or C4 positions remains to be determined. Because UDP-GlcNAc is a likely starting material for the biosynthesis of this sugar (17, 18), the acetamido group is more likely on carbon 2 and the glyceramido on position 4, making it a 2-acetamido 4-glyceramido 2,4,6-trideoxyhexose.

MS also permitted testing the role of pgl genes in the glycosylation of PilE with GATDH. We found that pglB, pglC, and pglD were necessary for pilin glycosylation with GATDH, as was the case for the glycosylation of N. gonorrhoeae MS11 pilin with DATDH (10). Because the obvious difference between the MS11 strain and the 8013 strain concerning the pgl genes was the presence of an insertion in the carboxyl-terminal portion of PglB (pglB2 allele), it was tempting to speculate that pglB was responsible for the difference of sugar. To test this hypothesis, we engineered an MS11 strain expressing the pglB2 allele from the 8013 strain. Strikingly, this strain expresses a pilin modified with a GATDH, showing that the difference in the pglB sequence determines the nature of the sugar on the pilin and that both species synthesize the appropriate metabolites for GATDH production. The carboxyl-terminal region of PglB therefore carries the biochemical property to transfer a glyceramido group onto the C4 of the sugar residue. We propose that, in strains that harbor the pglB2 allele, the following sequence of events takes place: PglD mediates the dehydration of UDP-GlcNAc C2 and C4, PglC transfers the amino group, and PglBCter adds the glyceramido group on C4. It will be interesting to extend the analysis of pilin glycosylation to a wider range of N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae strains as well as other bacterial species. We found that the pathogenic bacteria Vibrio parahemoliticus expresses a pglB gene with high homology to the N. meningitidis 8013 pglB2 gene (65.8% and 52.5% identity in the amino- and carboxyl-terminal portions of the protein, respectively), suggesting that this bacterium could also display GATDH residues on its type IV pilin subunits. To our knowledge, pilin glycosylation in Vibrio spp. has not been described. In the genome of V. parahemoliticus, the pglB2 gene is associated with a pglC and pglD homolog, suggesting that a complete glycosylation system could be present.

Comparison of the PglBCter sequence from the 8013 strain with the Prosite database of protein domains reveals that it contains an ATP-grasp domain (group 3). The ATP-grasp superfamily includes 17 groups of enzymes, catalyzing ATP-dependent ligation of a carboxylate-containing molecule to an amino group-containing molecule (28). The reaction catalyzed by PglB is therefore likely to require energy through consumption of ATP. Interestingly, group 3 of the ATP-grasp superfamily, to which PglB belongs, has no known function. Because our study demonstrates that PglBCter exhibits glyceramido transfer activity, it will be interesting to test whether other ATP-grasp_3 group members also have this activity.

It should be emphasized that the role of pilin glycosylation remains completely unknown. The existence of an alternative glycosylation due the insertion in the pglB gene in nearly 50% of clinical isolates raises the question of whether changing sugar modifications confers an advantage to the strains. Changing the structure of pilin glycosylation could be a form of immune escape by changing surface epitopes. In theory, this effect could modulate the ability of the bacteria to colonize the nasopharynx and thus provide an advantage for the bacteria, but there is no evidence either for or against this hypothesis. It is not known, for example, whether this epitope is immunogenic. Furthermore, because both sugars are equally represented in the N. meningitidis population, it could be argued that they both provide equally effective cloaking devices against the immune system.

In conclusion, the present study led to the identification of a monosaccharide modification of type IV pilin probably present in all of the strains expressing the pglB2 allele, which accounts for nearly half of the N. meningitidis clinical isolates. Strikingly, the GATDH residue identified here has not been described anywhere else to our knowledge. Furthermore, a new biochemical function is assigned to PglB2 as a glyceramido transferase, which belongs to the ATP-grasp family of proteins. To reach these results, an MS-based strategy for sugar identification was designed combining different MS techniques. MS analysis exploiting ISD followed by MS/MS led to demonstrative information on the sugar structure in a one-step analysis of a partially purified protein. This approach should prove useful for rapid and simple identification of sugars on glycosylated proteins.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions.

Unless otherwise noted, all N. meningitidis strains described in this study were derived from the 8013 clone 12 strain. N. gonorrhoeae MS11 strain was also used. Neisseria spp. were grown on GCB agar plates (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD) containing Kellog's supplements and, when required, 100 μg/ml kanamycin at 37°C in a moist atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Transformants of E. coli were grown on solid or liquid Luria–Bertani broth (Becton Dickinson) containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin. Mutants used in this study are described in SI Table 1. Several mutants described in this study were derived from a library of transposition mutants described elsewhere (24).

To transfer the pglB2 allele from the 8013 strain to the MS11 strain, the genomic region encompassing the insertion found in the pglB2 allele was amplified with the pglB F1 (5′-CTGTTCGACATCATCGCATCC-3′) and pglB R1 (5′-TCGGCAAACACGGGATTTG-3′) oligonucleotides starting from genomic DNA originating from an 8013 strain containing a transposon insertion in the HAD gene. The generated 4.5-kb fragment was cloned in the PCR2.1 Topo plasmid and checked by sequencing. The plasmid was used to transform the MS11 strain, and transformants were selected on kanamycin plates.

Pili Preparation.

Pili were prepared as previously described (29). The contents of four Petri dishes were harvested in 10 ml of 150 mM ethanolamine at pH 10.5. Pili were sheared off by vortexing during 1 min. Bacteria were centrifuged at 17,000 × g during 30 min. Pili were then precipitated by adding ammonium sulfate at a concentration of 10% to the supernatants, and samples were allowed to stand for 60 min. Precipitates were pelleted by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 30 min. Pellets were washed with PBS twice and resuspended in distilled water.

MS.

MALDI-TOF.

The molecular masses of the purified pili were determined by MALDI-TOF MS using a Voyager-DE Pro mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The MALDI-TOF spectrometer was operated in positive ion linear mode and was used with an accelerating voltage of 25 kV, grid voltage at 92.5%, and a delay time of 350 ns. Pili solutions were initially mixed with an equal volume of matrix prepared by using kit instruction (sinapinic acid; LaserBioLabs, Sophia-Antipolis, France), and 2 μl was allowed to crystallize on the MALDI plate.

FT-ICR.

Type IV pili protein solutions were desalted by C4 zip-tip (Millipore, Billerica, MA) purification and eluted in 10 μl of 73.5:23.5:3 MeOH/water/formic acid (vol/vol/vol). The same samples were used for FT-ICR and Q-TOF analyses.

Experiments were carried out with a 7-T APEX III FT-ICR mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) equipped with a 7-T actively shielded superconducting magnet and an infinity cell. The ionization source used was the Apollo nanoelectrospray source. Nanoelectrospray glass capillaries (Proxeon, Odense, Denmark) were filled with 2 μl of the protein solution, and each was subsequently opened by breaking the tapered end of the tip under a microscope. A stable spray was observed by applying a voltage of about −700 V between the needle (grounded) and the entrance of the glass capillary used for ion transfer. A source temperature of 50°C was used for all nanoelectrospray experiments. The estimated flow rate was 20–50 nl/min. Ions were stored in the source region in a hexapole guide for 1 s and pulsed into the detection cell through a series of electrostatic lenses. Ions were finally trapped in the cell by using SideKick and front and back trapping voltages of 0.9 and 0.95 V. Mass spectra were acquired from m/z 600–3,000 with 512,000 data points. For ISD, ions were dissociated by increasing the preskimmer voltage (up to 250 V) in the subsequent preskimmer region (≈1-Torr pressure). All spectra were deconvoluted into MH+ species by using XMASS 6.1.4 (Bruker Daltonics). Theoretical isotopic patterns were generated by using DataAnalysis 3.2 (Bruker Daltonics). An external mass calibration using NaI (2 mg/ml in isopropanol/water) was done daily.

Q-TOF.

Samples for electrospray were prepared as described above for FT-ICR. The MS/MS determination of the sugar structure was performed on a Q-TOF Premier (Waters). The Q-TOF Premier is a quadrupole, orthogonal acceleration TOF tandem mass spectrometer. The proteins were ionized by using nanoelectrospray ionization in positive mode (ZSpray). The source temperature was set to 80°C. The capillary and cone voltages were set to 3,000 and 40 or 80 V, respectively (80 V for ISD). The Q-TOF Premier instrument was operated in wide-pass quadrupole mode for MS experiments, with the TOF data being collected between m/z 400 and 2,000 with a low collision energy of 10 eV. Argon was used as the collision gas. Scans were collected for 1 s and accumulated to increase the signal/noise ratio. The MS/MS experiments were performed by using a variable collision energy (10–30 eV), which was optimized for each precursor ion. Mass Lynx 4.1 was used for both acquisition and data processing. Deconvolution of multiply charged ions into neutral species was realized by using MaxEnt1 in the mass range (10–25 kDa) with a resolution of 0.01 Da per channel. An external calibration in MS was done with clusters of phosphoric acid (0.01 M in 50:50 acetonitrile:H2O vol/vol). The mass range for the calibration was m/z 70–2,000.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank A. M. Lennon Dumenil for reviewing the manuscript. The work was funded by the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (Grant JC05-44953), and the Université René Descartes. F.L. was funded by the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale.

Abbreviations

- DATDH

2,4-diacetamido-2,4,6-trideoxyhexose

- GATDH

glyceramido acetamido trideoxyhexose

- ISD

in-source dissociation

- FT-ICR

Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance

- Q-TOF

quadrupole TOF

- MS/MS

tandem MS.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0705335104/DC1.

References

- 1.Szymanski CM, Wren BW. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:225–237. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caugant DA, Tzanakaki G, Kriz P. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2007;31:52–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2006.00052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nassif X, Bourdoulous S, Eugene E, Couraud PO. Trends Microbiol. 2002;10:227–232. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(02)02349-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mairey E, Genovesio A, Donnadieu E, Bernard C, Jaubert F, Pinard E, Seylaz J, Olivo-Marin JC, Nassif X, Dumenil G. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1939–1950. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swanson J. J Exp Med. 1973;137:571–589. doi: 10.1084/jem.137.3.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carbonnelle E, Helaine S, Prouvensier L, Nassif X, Pelicic V. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55:54–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parge HE, Forest KT, Hickey MJ, Christensen DA, Getzoff ED, Tainer JA. Nature. 1995;378:32–38. doi: 10.1038/378032a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stimson E, Virji M, Makepeace K, Dell A, Morris HR, Payne G, Saunders JR, Jennings MP, Barker S, Panico M, et al. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:1201–1214. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17061201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aas FE, Egge-Jacobsen W, Winther-Larsen HC, Lovold C, Hitchen PG, Dell A, Koomey M. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:27712–27723. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604324200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hegge FT, Hitchen PG, Aas FE, Kristiansen H, Lovold C, Egge-Jacobsen W, Panico M, Leong WY, Bull V, Virji M, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:10798–10803. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402397101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jennings MP, Virji M, Evans D, Foster V, Srikhanta YN, Steeghs L, van der Ley P, Moxon ER. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:975–984. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Power PM, Roddam LF, Dieckelmann M, Srikhanta YN, Tan YC, Berrington AW, Jennings MP. Microbiology. 2000;146:967–979. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-4-967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kahler CM, Martin LE, Tzeng YL, Miller YK, Sharkey K, Stephens DS, Davies JK. Infect Immun. 2001;69:3597–3604. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.6.3597-3604.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szymanski CM, Yao R, Ewing CP, Trust TJ, Guerry P. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:1022–1030. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wacker M, Linton D, Hitchen PG, Nita-Lazar M, Haslam SM, North SJ, Panico M, Morris HR, Dell A, Wren BW, Aebi M. Science. 2002;298:1790–1793. doi: 10.1126/science.298.5599.1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Young NM, Brisson JR, Kelly J, Watson DC, Tessier L, Lanthier PH, Jarrell HC, Cadotte N, St Michael F, Aberg E, Szymanski CM. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:42530–42539. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206114200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schoenhofen IC, McNally DJ, Vinogradov E, Whitfield D, Young NM, Dick S, Wakarchuk WW, Brisson JR, Logan SM. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:723–732. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511021200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olivier NB, Chen MM, Behr JR, Imperiali B. Biochemistry. 2006;45:13659–13669. doi: 10.1021/bi061456h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Power PM, Roddam LF, Rutter K, Fitzpatrick SZ, Srikhanta YN, Jennings MP. Mol Microbiol. 2003;49:833–847. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Power PM, Seib KL, Jennings MP. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;347:904–908. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.06.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meng F, Forbes AJ, Miller LM, Kelleher NL. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2005;24:126–134. doi: 10.1002/mas.20009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schirm M, Schoenhofen IC, Logan SM, Waldron KC, Thibault P. Anal Chem. 2005;77:7774–7782. doi: 10.1021/ac051316y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garavelli JS. Proteomics. 2004;4:1527–1533. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geoffroy MC, Floquet S, Metais A, Nassif X, Pelicic V. Genome Res. 2003;13:391–398. doi: 10.1101/gr.664303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stimson E, Virji M, Barker S, Panico M, Blench I, Saunders J, Payne G, Moxon ER, Dell A, Morris HR. Biochem J. 1996;316:29–33. doi: 10.1042/bj3160029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanisch FG, Green BN, Bateman R, Peter-Katalinic J. J Mass Spectrom. 1998;33:358–362. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9888(199804)33:4<358::AID-JMS642>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rademaker GJ, Pergantis SA, Blok-Tip L, Langridge JI, Kleen A, Thomas-Oates J. Anal Biochem. 1998;257:149–160. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Galperin MY, Koonin EV. Protein Sci. 1997;6:2639–2643. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560061218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Helaine S, Carbonnelle E, Prouvensier L, Beretti JL, Nassif X, Pelicic V. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55:65–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.