Abstract

Cellular organization into epithelial architecture maintains structural integrity and homeostasis by suppressing cell proliferation and apoptosis. However, it is unclear whether the epithelial organization is sufficient to block induction of cell-autonomous cell cycle progression and apoptotic sensitivity by activated oncogenes. We show that chronic activation of oncogenic c-Myc, starting in the developing 3D organotypic mammary acinar structures, results in hyperproliferation and transformed acinar morphology. Surprisingly, acute c-Myc activation in mature quiescent acini with established epithelial architecture fails to reinitiate the cell cycle or transform these structures. c-Myc does reinitiate the cell cycle in quiescent, but structurally unorganized, acini, which demonstrates that proper epithelial architecture is needed for the proliferation blockade. The capability of c-Myc to reinitiate the cell cycle in acinar structures is also restored by the loss of LKB1, a human homologue of the cell polarity protein PAR4. The epithelial architecture also restrains the apoptotic activity of c-Myc, but coactivation of c-Myc and a complementary TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand death receptor pathway can induce a strong Bim and Bid-mediated apoptotic response in the established acini. The results together expose surprising proliferation and apoptosis resistance of organized epithelial structures and identify a role for the polarity regulator LKB1 in the development of c–Myc-resistant cell organization.

Keywords: 3D culture, apoptosis

Epithelial cells are bound to each other via cell junctions and adhesions forming well structured and polarized sheets of cells anchored to a basement membrane. The epithelial sheets line, for example, internal organs such as lung alveoli or acini in the mammary gland (1, 2). The structural organization of epithelial cells, i.e., epithelial architecture, crucially controls basic epithelial cell processes, including proliferation, migration, adhesion, polarization, differentiation, and death (2). Interestingly, recent evidence from Drosophila models suggests that an intact epithelial structure also acts as a barrier against tumor development because inactivation of any of a number of genes linked to cell polarity can spontaneously induce neoplastic overgrowth or cooperate with active oncogenes in tumor development (3, 4).

3D organotypic epithelial culture models have provided new genetically tractable tools to address the role of human epithelial organization in control of normal and oncogene-driven cell proliferation (1, 5). A commonly used 3D culture procedure is to culture nontransformed mammary epithelial cells in extracellular matrix (ECM) gel extract (Matrigel). In this microenvironment, cells proliferate and eventually form proliferation arrested structures with acinus-like morphology and architecture (6). Such 3D culture models preserve epithelial structural organization and many physiological cell–cell and cell–ECM contacts, cell polarity, and secretory functions that epithelial cells lack in the 2D monolayer cultures (7).

Expression of oncogenes that are common in breast cancers, including active forms of ErBB2, EGFR, AKT, cyclinD1, CSF1R, or Bcl-2 in nontransformed mammary epithelial cells, leads to development of transformed acinar phenotypes in 3D, which mirror abnormalities commonly seen in human breast cancers. The abnormalities include unscheduled proliferation, enlargement of acinar size, blockade of apoptosis, polarity defects, and population of luminal space with cells (1). However, although it has become clear that oncogenes can deregulate the process of formation of architecture, it is less understood whether the established cell organization in mammalian epithelial structures regulates the transforming potential of oncogenes. Experiments with regulable forms of oncogenes can thus provide important insights into these questions.

In this study, we used a conditionally active form of c-Myc, MycERtm, where tm is tamoxifen, to analyze whether epithelial architecture modulates the dual proliferative and apoptotic function of oncogenic c-Myc (8). The data demonstrate that chronic c-Myc activation in developing 3D mammary epithelial structures induces hyperproliferation and spontaneous apoptosis and eventually leads to development of transformed structures with similar features observed in premalignant breast cancers. Surprisingly, acute c-Myc activation completely fails to induce cell cycle progression, apoptosis, or transformation in the established, organized epithelial structures. We show that disruption of epithelial cell organization by the lack of proper microenvironment or silencing of LKB1, a human homologue of the cell polarity protein PAR4, restores the ability of c-Myc to reinitiate the cell cycle and induce apoptosis. We also show that even though organized epithelial structure restrains the apoptotic c-Myc function the organization cannot protect cells against apoptosis induced by coactivation of c-Myc and TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) death receptor pathways. This study demonstrates in a 3D culture model that human epithelial cell organization forcefully suppresses transforming, proliferative, and apoptotic potential of c-Myc oncogene and links epithelial structure regulators to the control of oncogene function.

Results

Activation of c-Myc During Early Acinar Morphogenesis Results in Hyperproliferation and Transformation of the Developing Structures.

To explore the proliferative and apoptotic function of c-Myc in 3D culture, we retrovirally introduced a conditionally active form of c-Myc, MycERtm, or a biologically inactive mutant MycΔERtm into MCF10A mammary epithelial cells and human telomerase immortalized mammary epithelial cells [supporting information (SI) Fig. 6A]. Activation of MycERtm by 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT) induced cell cycle reentry in quiescent 2D mammary epithelial cell cultures, which confirms that MycERtm is biologically active (SI Fig. 6 B and C). Activation of control MycΔERtm did not induce cell cycle progression in these conditions. In contrast to fibroblasts (8), c-Myc did not induce apoptosis in mammary epithelial cells upon growth factor deprivation (SI Fig. 6D).

To determine whether c-Myc activation interferes with growth and morphogenesis of 3D acini, MCF10A MycERtm cells were seeded in Matrigel, and c-Myc was activated the next day by the addition of 4-OHT (day 1). We observed that the acini forming under the influence of active c-Myc were larger than the control acini after 10 days of culture (Fig. 1A). On day 15 the c-Myc acini reached maximum size and the growth ceased even though active c-Myc was expressed at high levels (Fig. 1A and SI Fig. 7A). The average diameter of c-Myc acini on day 25 was 1.4 times larger than that of controls (P < 0.0001 by Student's t test). Consistent with the observed size increase, the acini with active c-Myc also exhibited a prolonged period of cell proliferation (Fig. 1B). Normally, the mitotic activity within the acini sharply declined between days 10 and 15 of morphogenesis. In contrast, the mitotic activity in c-Myc acini remained high throughout the studied 20-day period.

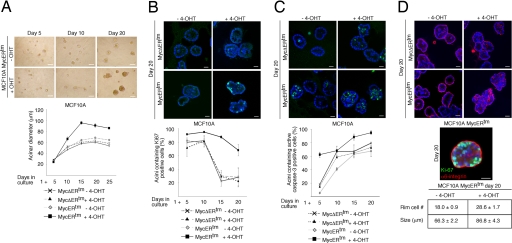

Fig. 1.

Activation of c-Myc at the early stage of acinar morphogenesis results in abnormal acini. (A) (Upper) Phase-contrast micrographs of MCF10A MycERtm acini grown in the presence of 4-OHT or carrier control for the indicated time periods. MCF10A MycERtm or MycΔERtm cells were embedded in Matrigel and 4-OHT or carrier control treatment was started on day 1. (Lower) Shown is growth of the acinar size, plotted as mean diameters of the acini at different time points (mean ± SEM). (B) (Upper) Shown are day-20 acini immunostained with Ki-67 antibody to detect cell proliferation. (Lower) Shown are percentages of acini at each time point exhibiting ≥1 Ki67-positive cells. (C) (Upper) Shown are day-20 acini immunostained with an antibody recognizing active caspase-3 to detect apoptosis. (Lower) Percentages of acini containing ≥1 active caspase-3-positive cells are shown. (D) (Top) Day-20 acini immunostained with α6-integrin antibodies to display acinar morphology and cell polarity. (Middle) The image shows that both the polarized, basal α6-integrin-expressing ECM facing cells and the inner cells show proliferative activity (Ki-67). (Bottom) The number of ECM facing outer cells, localizing at the rim of acini is shown. Values represent mean ± SEM of three independent experiments, where at least 90 acini per experiment were counted. (Scale bars: 100 μm, A; 20 μm, B–D).

To determine whether an increased apoptotic rate possibly counterbalanced the c-Myc-induced cell proliferation to inhibit continuous growth of acinar size, we examined the level of apoptosis. As reported (9), we observed virtually no apoptosis in the developing acini until day 5 (Fig. 1C). Thereafter as the structure grew, central cells inside the structure became deprived of ECM contacts and underwent apoptosis, which gave rise to a hollow lumen (9). As expected, after day 5 we commonly observed individual apoptotic cells in the luminal area (Fig. 1C Upper). In contrast to this pattern of apoptosis, the c-Myc acini contained increased amounts of apoptotic cells in the outer cell layer and lumen and at an early stage (day 5) of development (Fig. 1C Lower). We infer from these results that the increased apoptosis in the c-Myc acini at least in part explains the cessation of size growth.

c-Myc also transformed the acinar morphology. The c-Myc acini were typically misshapen and nonsymmetrical rather than rounded structures (Fig. 1D). In addition, the luminal space was densely populated with cells. To analyze basal cell polarity, we examined the acini for localization of α6-integrin. Fig. 1D shows that cells residing in the luminal area show diffuse nonpolarized staining pattern, whereas the outer ECM-facing cells express α6-integrin exclusively at the basal side. Thus, c-Myc does not disrupt the outer acinar cell basal polarity. When the structures were coimmunostained for Ki-67 and α6-integrin, we observed double-positive cells in both the luminal population and among polarized cells in contact with ECM (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, the numbers of ECM-facing cells were counted from the confocal images, and the c-Myc acini clearly contained more cells in the “rim” than controls (Fig. 1D Bottom). The data suggest that c-Myc drives cell proliferation in all acinar compartments, including nonpolarized luminal cells and polarized ECM-facing cells. This c-Myc effect leads to hyperplasia and morphological alterations, including distorted morphology and filling of the lumen. In this respect, the phenotype of the in vitro-formed c-Myc acini bear resemblance to premalignant breast cancer lesions that are precursors of ductal carcinoma in situ.

Activation of c-Myc Fails to Reinitiate the Cell Cycle in Established Acinar Structures.

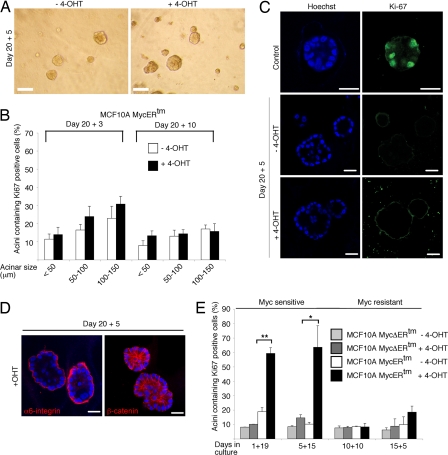

To determine whether c-Myc elicits mitogenic response in acini with established epithelial organization, the MCF10A and human telomerase immortalized mammary epithelial cells expressing MycERtm and control cells were first cultured for 20 days in Matrigel, and, subsequently, c-Myc was activated. The structures were fixed 3, 5, or 10 days after c-Myc activation and examined. Surprisingly, in these preformed acinar structures c-Myc completely failed to induce changes in morphology or size (Fig. 2A) or trigger proliferative activity (Fig. 2 B and C and SI Fig. 7B). We quantitated the proliferative activity in the average-size acini and in minority groups of small (≤50 μm in diameter) and large (100–150 μm in diameter) acini. However, no c-Myc-dependent increase in the proliferative activity was observed in any of the groups. The basal expression pattern of α6-integrin and the localization of β-catenin at cell–cell junctions was also preserved (Fig. 2D). Thus, the data suggest that at a certain point of acinar morphogenesis c-Myc loses its ability to promote epithelial cell proliferation. To pinpoint the window of c-Myc responsiveness, we activated c-Myc at different time points in 3D cultures and fixed the structures on day 20. The results show that activation of c-Myc in day-5 acinar structures (5-day growth in Matrigel + 15-day c-Myc activation) but no longer in day-10 structures (10 + 10) produced acini with proliferative activity on day 20 (Fig. 2E). Notably, the 10-day c-Myc activation induced hyperproliferation if c-Myc was activated on day 1 (Fig. 1). Therefore, we conclude that epithelial cells lose responsiveness to the mitogenic action of c-Myc between days 5 and 10 of acinar morphogenesis. Notably, the acinar cells lose responsiveness to c-Myc during the period when the organized epithelial architecture forms (6).

Fig. 2.

c-Myc fails to reinitiate the cell cycle or disrupt architecture in mature MCF10A acinar structures. (A) Phase-contrast micrographs of MCF10A MycERtm acini, which were first allowed to form for 20 days in Matrigel and subsequently treated with 4-OHT for 5 days (20 + 5). (B) Quantitation of Ki-67 positivity. Mature (day 20) MCF10A MycERtm acini were treated with 4-OHT for 3 or 10 days, and Ki-67 positivity was scored in the average-sized acini and the minor fractions of small and large acini. (C) Representative images of Ki-67-immunostained MCF10A MycERtm acini, which were allowed to mature for 20 days and treated with 4-OHT for 5 days. Control shows typical day-10 acinus with Ki-67-positive cells. (D) c-Myc does not disrupt architecture of preformed acinar structures. Representative images of MCF10A MycERtm acini, which were first allowed to form for 20 days and subsequently treated with 4-OHT for 5 days, are shown. (E) MCF10A acini become c-Myc-resistant during morphogenesis. MCF10A MycERtm and MycΔERtm cells were embedded in Matrigel on day 0, after which the treatment of developing structures with 4-OHT or carrier control was started on days 1, 5, 10, or 15 (marked as 1+19, 5+15, 10+10, and 15+5, respectively). All samples were fixed and immunostained for Ki-67 on day 20. Values represent mean ± SEM of three independent experiments, where at least 90 acini per experiment were counted. (Scale bars: 100 μm, A; 20 μm, C and D.)

Organized Epithelial Architecture Is Critical for Suppression of Proliferative c-Myc Function.

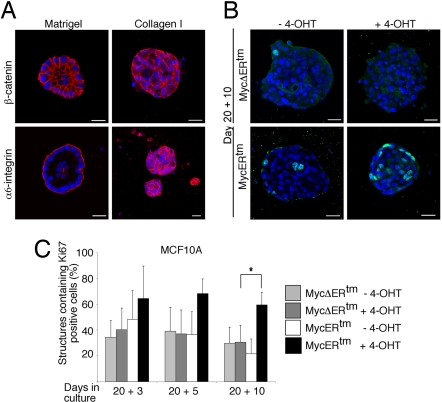

Matrigel as an ECM substituent strongly promotes differentiation of mammary epithelial cells into secretory cells in the context of the formation of polarized glandular architecture (10). Mammary epithelial cells also form cysts in collagen I matrix, but collagen I only weakly promotes differentiation and the cysts fail to develop into polarized and organized epithelial structures (11). We generated MCF10A cysts in collagen I matrix and determined the proliferative effects of c-Myc in these structures. On day 20, these collagen I-grown cysts and the Matrigel-grown acinar structures were about the same size (Fig. 3A), and the majority of collagen I cysts were also found to be proliferation-arrested (Fig. 3 B and C). However, the cysts lacked lumen, and, furthermore, the disorganized localization of β-catenin and diffuse α6-integrin expression (depicted in Fig. 3A) indicated a lack of cell organization and polarity. Strikingly, whereas c-Myc failed to reinitiate the cell cycle in the epithelial structures developed in Matrigel, activation of c-Myc clearly promoted proliferation in the cysts developed in collagen I (Fig. 3C). The data underscore the importance of epithelial architecture and polarity in blocking the proliferative c-Myc function.

Fig. 3.

c-Myc reinitiates cell cycle in mammary epithelial structures formed in collagen I matrix. (A) Representative images of day-20 MCF10A structures formed either in Matrigel or collagen I matrix. (B) Representative images of MCF10A MycERtm or MycΔERtm cells grown in collagen I gel for 20 days and thereafter treated with 4-OHT or carrier control for 10 days. (C) Quantitation of Ki-67 positivity. Day-20 structures were treated with 4-OHT for 3, 5, or 10 days. Structures containing ≥1 Ki-67-positive cells were scored as positive. Values represent mean ± SEM of three independent experiments, where at least 90 structures were counted per experiment. (Scale bars: 20 μm, A and B.)

Silencing of LKB1 Enables c-Myc to Reinitiate the Cell Cycle in Acinar Structures.

To further assess the significance of epithelial organization in restraining the oncogenic properties of c-Myc, we silenced LKB1 in MCF10A MycERtm cells by a lentiviral short hairpin RNA (shRNA) approach (Fig. 4A). LKB1 serine/threonine kinase belongs to a functionally conserved partitioning defective (PAR) protein family, which regulates cell polarity in Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster (12). Recent findings have also shown evidence that human LKB1 (PAR4) and its target AMP-activated protein kinase control polarity and assembly of tight junction structures in mammalian epithelial cells (13–15). LKB1 is also defined as a human tumor suppressor protein because germ-line Lkb1-inactivating mutations characterize Peutz-Jeghers cancer syndrome families, and, furthermore, somatic alterations or reduced gene expression of LKB1 are found in several carcinomas, including carcinomas of breast (16–20).

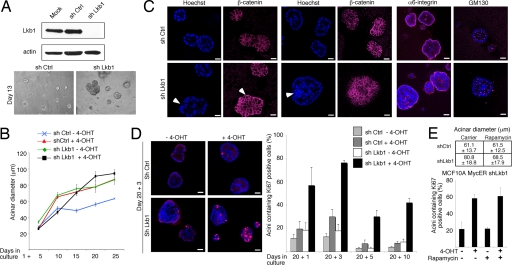

Fig. 4.

Disruption of architecture by loss of LKB1 allows c-Myc to reinitiate the cell cycle in acinar structures. (A) (Upper) Western blot analysis demonstrating lentiviral shRNA-mediated silencing of LKB1 in MCF10A cells. (Lower) Representative images showing morphology of control and LKB1-deficient acini. (B) The growth of the acinar size is plotted as mean diameters of the acini at different time points (mean ± SEM). Experiments were performed as in Fig. 1. (C) Representative images of day-15 control and LKB1-deficient MCF10A acini grown in the absence of 4-OHT and stained with either β-catenin, α6-integrin, or Golgi protein GM130 to visualize architecture and cell polarity. (D) Representative images and Ki-67 quantitation of control and LKB1-deficient MCF10A MycERtm acini grown in Matrigel for 20 days and thereafter treated with 4-OHT for 1, 3, 5, or 10 days. (E) mTOR is required for acinar overgrowth but is dispensable for c-Myc-induced reinitiation of the cell cycle in LKB1-deficient MCF10A acini. The acini were allowed to form in the presence of 20 mM rapamycin, a highly specific mTOR inhibitor. (Upper) Acinar diameters on day 23 are shown. (Lower) c-Myc was activated on day 20, and the acini were cultured for 3 days in the presence of active c-Myc and rapamycin. Shown is the quantitation of Ki-67 positivity in the structures. Values represent mean ± SEM of three independent experiments, where at least 90 structures were counted per experiment. (Magnification: ×10, A Lower; scale bars: 20 μm, C and D.)

The LKB1-deficient epithelial cells formed abnormally large acini with transformed, asymmetric, and uneven gross morphology (Fig. 4 A–C). The ultrastructure of LKB1-deficient acini was also disorganized and complex. Typical features of these acini included partial multilayering of acinar cells (Fig. 4C Left, arrows), outward bulges formed of cells uneven in size and distribution (visualized with β-catenin staining in Fig. 4C Left) and large cell aggregates intruding into luminal cavity (Fig. 4C Center) and often filling of the whole luminal space (SI Fig. 8A). The cells of the outer layer exhibited normal basal polarity (α6-integrin) and apical polarity determined by the apical localization of cis-Golgi matrix protein GM130 (Fig. 4C). However, the apical polarization was lost in the groups of cells intruding into the luminal cavity (Fig. 4C). Altogether, the absence of LKB1 leads to gross abnormalities in the structure and partial loss of cell polarity in the 3D acini.

When the proliferative activity was analyzed, we found that cell cycle exit of LKB1-deficient acinar cells was delayed during morphogenesis (data not shown). However, by day 20 the majority of acini were comprised of only quiescent cells (Fig. 4D). Loss of LKB1 did not block luminal apoptosis (SI Fig. 8B), and, therefore, the morphological abnormalities, including the presence of cells in the luminal area, are rather attributable to hyperproliferation than the lack of apoptosis. We next determined whether c-Myc induces cell cycle progression in quiescent LKB1-deficient acini. Strikingly, activation of c-Myc for 1, 3, 5, or 10 days induced pronounced cell cycle reentry, whereas cells in the control acini remained quiescent (Fig. 4D Right). Notably, only 24-h c-Myc activation was sufficient to activate the cell cycle in the majority of the LKB1-deficient acini. These data show that Lkb1-dependent disruption of epithelial structure unveils the cell cycle-promoting function of oncogenic c-Myc. Under conditions of energetic stress, LKB1 deficiency leads to abberrant regulation of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) protein (21). Interestingly, rapamycin partially reversed the LKB1 deficiency-mediated overgrowth of acini, which demonstrates a role for mTOR in hyperproliferation of LKB1-deficient acini (Fig. 4E). However, rapamycin did not inhibit the reinitiation of the cell cycle by c-Myc (Fig. 4E and SI Fig. 9), which indicates that the loss of LKB1 activity dismantles the proliferation block in organized acini independently of mTOR.

Organized Epithelial Architecture Regulates Sensitivity to the Apoptotic c-Myc Function.

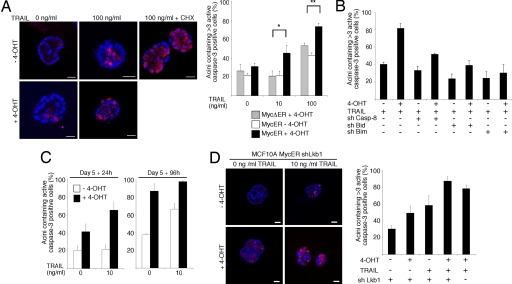

Finally, we wanted to determine whether the epithelial cell organization also regulates the apoptotic c-Myc function. Activation of c-Myc did not spontaneously induce apoptosis in organized 3D cultures or 2D cell cultures (SI Fig. 10 and data not shown). However, in 2D cell cultures c-Myc strongly sensitized cells to apoptotic action of TRAIL, etoposide, and cycloheximide by increasing the apoptotic effects of these agents by 4- to 5-fold (SI Fig. 10 A–C). To closer inspect apoptotic function of c-Myc in the established acini, MCF10A MycERtm cells were cultured in Matrigel for 20 days, c-Myc was activated, and the cultures were treated with TRAIL for 96 h. We observed that combined activation of c-Myc and TRAIL pathways strongly promoted apoptosis in 3D acini (Fig. 5A and SI Fig. 10D). Notably, >50% of the acini containing active c-Myc showed increased apoptosis in response to sublethal 10 ng/ml TRAIL concentration (Fig. 5A). We also noticed that c-Myc and TRAIL killed cells throughout the acinus, including the polarized cells facing ECM (SI Fig. 10E). To determine whether the apoptosis involved the mitochondrial branch of death receptor signaling, we silenced by lentiviral shRNA constructs caspase-8 and the proapoptotic BH3-only members of the Bcl-2 family, Bid and Bim. Western blot analysis showed 45% and 52% reduction in caspase-8 and Bim expression levels, respectively, and the Bid shRNA silenced Bid expression below a detectable level (ref. 22 and data not shown). The acinar apoptosis coinduced by c-Myc and TRAIL required intact caspase-8, Bid, and Bim (Fig. 5B), which indicates involvement of the mitochondrial route.

Fig. 5.

Organized epithelial architecture regulates the apoptotic c-Myc function. (A) (Left) Representative images of MCF10A MycERtm acini immunostained with anti-active caspase-3 antibody. Day-20 MCF10A MycERtm acini were treated with 4-OHT for 24 h, and, subsequently, the acini were treated for 96 h with 0 or 100 ng/ml of TRAIL. TRAIL and 10 μg/ml cycloheximide (CHX) was used as a positive control. (Right) Quantitation of apoptosis. Acini containing >3 active caspase-3-positive cells were scored positive in the assay. (B) Caspase-8, Bid, and Bim mediate the acinar apoptosis induced by c-Myc and TRAIL. Shown is the quantitation of apoptosis in the MCF10A MycERtm acini expressing shRNA constructs silencing either caspase-8, Bid, or Bim. The day-20 acini were treated with 100 ng/ml TRAIL, and the resulting apoptosis was scored as in A. (C) Apoptotic sensitivity of the immature unorganized acini. The day-5 MCF10A MycERtm acini were first treated 24 h with 4-OHT and then either 24 h (Left) or 96 h (Right) with 10 ng/ml TRAIL. The acini containing ≥1 active caspase-3-positive cells were scored as positive. (D) Apoptotic sensitivity of the disorganized Lkb1-deficient acini. (Left) Representative images of the day-20 MCF10A MycERtm shLkb1 acini treated with 4-OHT for 24 h and thereafter for 96 h with 10 ng/ml of TRAIL. (Right) Quantitation of apoptosis. Acini containing >3 active caspase-3-positive cells were scored positive. Values represent mean ± SEM of three independent experiments, where at least 90 acini were counted per experiment. (Scale bars: 20 μm, A and D.)

To analyze the apoptotic activity of c-Myc in unorganized acini, c-Myc was activated either in immature day-5 acini (Fig. 5C) or disorganized day-20 LKB1-deficient acini (Fig. 5D). The immature acini were extremely sensitive to the apoptotic action of c-Myc and TRAIL (Fig. 5C; note the early 24-h time point). However, the analyses of the acini also showed that either c-Myc or low 10 ng/ml concentration of TRAIL induced a substantial amount of apoptosis alone. Therefore, the dramatic apoptosis seen in the unstructured acini was rather caused by additive than synergistic effect of c-Myc and TRAIL. This finding contrasts to the clearly synergistic activation of apoptosis by c-Myc and TRAIL in the organized acini. The analyses of LKB1-deficient acini also demonstrated that activation of a single apoptotic pathway (c-Myc or TRAIL) was sufficient to kill cells in disorganized acini (Fig. 5D). Thus, an established epithelial cell organization protects the member cells against spontaneous induction of apoptosis by c-Myc but fails to suppress the c-Myc-dependent sensitization to death.

Discussion

The development of epithelial acinar structures in 3D Matrigel culture follows defined morphogenetic steps, which include formation of cell polarity, entry of acinar cells into quiescence, and assembly of cell–cell junctions and cell–ECM contacts (1). Here, we demonstrate that formation of this type of organized epithelial structure crucially affects the proliferative function of c-Myc oncogene. Our results show that chronic activation of c-Myc during early acinar morphogenesis extends the proliferative period, disrupts the size control of the acini, and gives rise to transformed phenotype. However, the developing acinar structures become resistant to the proliferative and transforming effects of c-Myc during acinar morphogenesis and, in the established acini even a c-Myc activity lasting >10 days cannot reinitiate the cell cycle or induce any noticeable morphological or ultrastructural change. The MCF10A acini acquire c-Myc resistance during the time period when they establish structured cell organization and hollow architecture (6). Notably, acinar cells enter quiescence after the organized structure is formed (day 10), and, therefore, we believe that formation of the epithelial architecture rather than quiescence is critical for acquisition of c-Myc resistance. Consistent with this view, c-Myc is able to reinitiate the cell cycle in quiescent, but unstructured, mammary epithelial cysts formed in collagen I matrix.

Previous studies in Drosophila have demonstrated that while Ras or Notch have only mild proliferative effects in the monolayer columnar epithelium of eye disk, these oncogenes induce overproliferation and tumors in structurally abnormal epithelial tissue lacking polarity-controlling genes, including scribble, discs large or lethal giant larvae (4, 23). As an interesting analogy to these Drosophila models demonstrating interaction between epithelial structure and oncogene function, our results show that disruption of epithelial structure by loss of polarity gene LKB1 (PAR4) function enables c-Myc to induce cell cycle activity in 3D epithelial acini. Recently, activation of LKB1 by upstream effector STRAD has been shown to cell-autonomously activate polarization program in intestinal epithelial cells (13) and Peutz-Jeghers syndrome-associated C-terminal LKB1 mutants appear to interfere with this polarity function of LKB1 (20). Notably, recent papers (13–15) also suggest that the LKB1-AMPK branch in this signaling pathway regulates formation of tight junction structures. Our results show that loss of LKB1 activity leads to extensive disruption of mammalian epithelial architecture, which highlights the importance of the LKB1 pathway in the regulation of cell polarity and epithelial architecture in higher organisms. Interestingly, whereas deregulation of the LKB1–mTOR axis was required for the acinar overgrowth, mTOR was dispensable for the LKB1 pathway that liberated the cell cycle entry. Therefore, we favor a model that c-Myc-induced reinitiation of the cell cycle is linked to compromised epithelial architecture and not to cooperation of c-Myc with the LKB1–mTOR proliferation pathway. LKB1 has an antioncogenic function, and it will be interesting to explore whether the loss of LKB1 activity-mediated tumor progression involves disruption of epithelial polarity. However, the complete loss of LKB1 activity is embryonic lethal in mice (24), and therefore, these questions can be thoroughly addressed only with future inducible systems. Interestingly, ectopic dimerization of ErbB2 in established 3D MCF10A acini triggers massive overgrowth, loss of cell polarity, and disruption of acinar structure, and of these effects both the polarity and structure changes require interaction of ErbB2 with PAR6 (25). These data suggest that PAR proteins have multifaceted tumor suppressor functions linked to their roles in the control of cell polarity and epithelial structure.

Previous data have shown that polarized architecture of epithelial structures confers resistance to various apoptotic insults, including chemotherapeutic agents and death receptor ligands (11, 26). The present study shows that organized structure also protects cells against apoptotic c-Myc activity and, in addition, exposes an apoptotic pathway that can bypass protection by cell organization. According to our previous data, c-Myc preactivates the proapoptotic multidomain Bcl-2 family member Bak in epithelial cells, whereas TRAIL activates a complementary apoptotic pathway via caspase-8-mediated activating cleavage of Bid (22). The present study also shows genetic evidence for the involvement of a previously identified apoptotic c-Myc target Bim (27) in the apoptotic synergy. We speculate that activation of c-Myc unleashes a “BH3 load” that is sufficient to kill cells of the unstructured epithelium. However, structured epithelium protects cells from death, and in these conditions a substantial increase in BH3 load, including cleaved Bid, is needed to induce mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization and subsequent apoptosis.

Finally, the present findings may shed light on causes of long latency typically characterizing c-Myc-dependent tumorigenesis in mammary tissue. The tissue architecture itself, which is resistant to oncogenic activities attempting to reinitiate the cell cycle, can be the first barrier for tumorigenesis. Eventually, c-Myc may promote cell proliferation also in the acinar context if assisted through complementing action of oncogenic collaborators or if the tissue dedifferentiates or the microenvironment changes into growth permissive. Thus, rather than acting as an initiator of cell proliferation, c-Myc may sustain cell proliferation under suboptimal growth factor supply and present a growth advantage for tumor cells that have crossed the first proliferative barriers. However, expansion of c-Myc-driven unorganized tumor tissue also requires blockade of apoptosis, which is the other barrier for c-Myc-dependent mammary tumorigenesis.

In summary, our data show that an organized epithelial structure is a powerful restraint against oncogene-driven, unscheduled proliferation and apoptosis. The present approach combining genetically tractable 3D culture and regulable c-Myc can be used to identify novel epithelial polarity and structure regulators mediating proliferation and apoptosis resistance and to expose potential tumor suppressor genes and functions. Our present data reveal a role for the polarity gene LKB1 in the formation of c-Myc-restraining epithelial organization, and future in vivo analyses will help clarify whether deficiencies in the PAR protein network cooperate with c-Myc in tumorigenesis.

Experimental Procedures

Reagents.

The following primary antibodies were used: monoclonal c-Myc (9E10; a kind gift from Gerard Evan, University of California, San Francisco, CA), actin (monoclonal; Sigma, St. Louis, MO), Ki-67 (polyclonal; NovoCastra Laboratories, Newcastle, U.K.), cytochrome c, β-catenin, GM-130, and E-cadherin (all monoclonal; BD Transduction Laboratories, Franklin Lakes, NJ), active caspase-3 and phospho-S6 (Ser-235/236) (polyclonal; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), α6-integrin subunit antibody (monoclonal; Cymbus Biotechnologies, Chandlers Ford, U.K.), and Lkb1 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). In both 2D and 3D culture experiments 100 nM 4-OHT (Sigma; diluted from 1 mM stock) was used to activate MycERtm or MycΔERtm constructs.

Recombinant Viruses and Transduction Protocols.

pBabe-puro MycERtm and pBabe-puro MycΔERtm retroviral constructs were generous gifts from Gerard Evan, and pWZL h-TERT vector was from Martin McMahon (University of California, San Francisco, CA) and Robert A. Weinberg (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA). Retroviruses were produced in the Phoenix Ampho packaging cell line (from Garry Nolan, Stanford University, Stanford, CA) as described in SI Text. Lentiviruses were produced as described in SI Text using packaging constructs and protocols provided by the Biomedicum Virus Core Facility.

2D Cell Culture.

MCF10A cells were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA), and primary human mammary epithelial cells were from Cambrex (East Rutherford, NJ). Both cell lines were cultured in human mammary epithelial cell basal growth media MCDB 170 (US Biological, Swampscott, MA) supplemented with 70 μg/ml bovine pituitary extract (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY), 5 μg/ml insulin, 0.5 μg/ml hydrocortisone, 5 ng/ml epidermal growth factor, 5 μg/ml transferrin, 10−5 M isoproterenol (all from Sigma), and antibiotics (50 μg/ml amphotericin B and 50 μg/ml gentamicin (both from Sigma). The protocols for Western blot analysis, immunostaining, and immunofluorescence image acquisition are provided in SI Text.

3D Organotypic Culture.

Basement membrane from Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm mouse sarcoma (Matrigel; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) was prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions. Confluent cells were trypsinized, and 1,500 cells per well were seeded on eight-chamber slides coated with Matrigel. In collagen I experiments, 1,500 cells per well were seeded on eight-well chamber slides coated with 3 mg/ml of collagen I (Rat Collagen I, Cultrex; Trevigen, Gaithersburg, MD) gelled according to the manufacturer's protocol. Media were refreshed every fourth day in both cultures. The protocols for Western blot analysis, immunostaining, and confocal immunofluorescence image acquisition are provided in SI Text.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank pathologist Dr Ari Ristimäki for critical review of the manuscript and members of J.K.'s laboratory for discussions and technical assistance. The Biomedicum Helsinki Molecular Imaging Unit, Biocentrum Helsinki Systems Biology Intiative, and Biomedicum Virus Core Facility are acknowledged for reagents and excellent technical support. This study was funded by the Academy of Finland, the National Technology Agency Tekes, the Sigrid Juselius Foundation, Helsinki University Central Hospital, the Lilly Foundation, and the Juliana von Wendt Foundation.

Abbreviations

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- PAR

partitioning defective

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- 4-OHT

4-hydroxytamoxifen

- shRNA

short hairpin RNA

- TRAIL

TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0704677104/DC1.

References

- 1.Debnath J, Brugge JS. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:675–688. doi: 10.1038/nrc1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Brien LE, Zegers MM, Mostov KE. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:531–537. doi: 10.1038/nrm859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bilder D. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1909–1925. doi: 10.1101/gad.1211604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pagliarini RA, Xu T. Science. 2003;302:1227–1231. doi: 10.1126/science.1088474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmeichel KL, Bissell MJ. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:2377–2388. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Debnath J, Muthuswamy SK, Brugge JS. Methods. 2003;30:256–268. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(03)00032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barcellos-Hoff MH, Aggeler J, Ram TG, Bissell MJ. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1989;105:223–235. doi: 10.1242/dev.105.2.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pelengaris S, Khan M, Evan G. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:764–776. doi: 10.1038/nrc904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Debnath J, Mills KR, Collins NL, Reginato MJ, Muthuswamy SK, Brugge JS. Cell. 2002;111:29–40. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li ML, Aggeler J, Farson DA, Hatier C, Hassell J, Bissell MJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:136–140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.1.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weaver VM, Lelievre S, Lakins JN, Chrenek MA, Jones JC, Giancotti F, Werb Z, Bissell MJ. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:205–216. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00125-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baas AF, Smit L, Clevers H. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:312–319. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baas AF, Kuipers J, van der Wel NN, Batlle E, Koerten HK, Peters PJ, Clevers HC. Cell. 2004;116:457–466. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00114-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang L, Li J, Young LH, Caplan MJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:17272–17277. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608531103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng B, Cantley LC. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:819–822. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610157104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forster LF, Defres S, Goudie DR, Baty DU, Carey FA. J Clin Pathol. 2000;53:791–793. doi: 10.1136/jcp.53.10.791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fenton H, Carlile B, Montgomery EA, Carraway H, Herman J, Sahin F, Su GH, Argani P. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2006;14:146–153. doi: 10.1097/01.pai.0000176157.07908.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katajisto P, Vallenius T, Vaahtomeri K, Ekman N, Udd L, Tiainen M, Makela TP. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1775:63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhuang ZG, Di GH, Shen ZZ, Ding J, Shao ZM. Mol Cancer Res. 2006;4:843–849. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forcet C, Etienne-Manneville S, Gaude H, Fournier L, Debilly S, Salmi M, Baas A, Olschwang S, Clevers H, Billaud M. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:1283–1292. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shaw RJ, Bardeesy N, Manning BD, Lopez L, Kosmatka M, DePinho RA, Cantley LC. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:91–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nieminen AI, Partanen JI, Hau A, Klefstrom J. EMBO J. 2007;26:1055–1067. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brumby AM, Richardson HE. EMBO J. 2003;22:5769–5779. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ylikorkala A, Rossi DJ, Korsisaari N, Luukko K, Alitalo K, Henkemeyer M, Makela TP. Science. 2001;293:1323–1326. doi: 10.1126/science.1062074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aranda V, Haire T, Nolan ME, Calarco JP, Rosenberg AZ, Fawcett JP, Pawson T, Muthuswamy SK. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1235–1245. doi: 10.1038/ncb1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boudreau N, Werb Z, Bissell MJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3509–3513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Egle A, Harris AW, Bouillet P, Cory S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:6164–6169. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401471101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.