Abstract

Chemotactic cytokines (chemokines) attract immune cells, although their original evolutionary role may relate more closely with embryonic development. We noted differential expression of the chemokine receptor CXCR7 (RDC-1) on marginal zone B cells, a cell type associated with autoimmune diseases. We generated Cxcr7−/− mice but found that CXCR7 deficiency had little effect on B cell composition. However, most Cxcr7−/− mice died at birth with ventricular septal defects and semilunar heart valve malformation. Conditional deletion of Cxcr7 in endothelium, using Tie2-Cre transgenic mice, recapitulated this phenotype. Gene profiling of Cxcr7−/− heart valve leaflets revealed a defect in the expression of factors essential for valve formation, vessel protection, or endothelial cell growth and survival. We confirmed that the principal chemokine ligand for CXCR7 was CXCL12/SDF-1, which also binds CXCR4. CXCL12 did not induce signaling through CXCR7; however, CXCR7 formed functional heterodimers with CXCR4 and enhanced CXCL12-induced signaling. Our results reveal a specialized role for CXCR7 in endothelial biology and valve development and highlight the distinct developmental role of evolutionary conserved chemokine receptors such as CXCR7 and CXCR4.

Keywords: chemokines, heart, heterodimerization, immunology, endothelium

Chemokines are chemoattractant cytokines that bind to G protein-coupled seven-transmembrane receptors (GPCRs). They facilitate leukocyte migration but can also play a role in embryogenesis and angiogenesis (1, 2). CXCL12 (SDF-1) and its receptor CXCR4 are essential for heart, CNS, and blood vessel development, as well as B cell lymphopoiesis (3–7). Targeted deletion of Cxcl12 or Cxcr4 in the mouse leads to similar phenotypes, including ventricular septal defects, disorganized cerebellum, impaired hematopoiesis, and embryonic lethality between embryonic day (E)15 and E18 of gestation. Thus, CXCL12 and CXCR4 were long thought to be a monogamous pair. However, recent studies show that CXCL12 binds to an additional chemokine receptor, CXCR7 (RDC1/Cmkor1) (8, 9). In addition to CXCL12, CXCR7 binds to the chemokine CXCL11, although with a lower affinity (9). Cxcr7 encodes a protein highly conserved in mammals with >91% identity and 95% similarity between human, mouse, and dog proteins. It was first identified as an orphan GPCR expressed in the human thyroid and related to the chemokine receptor CXCR2 (10). Both CXCR7 and CXCR4 are expressed in a wide range of tissues in humans and are up-regulated in some tumors (9, 11–13). Similar to CXCR4, CXCR7 can facilitate angiogenesis (9, 14), and blockade of CXCR7 (9) or CXCR4 (12) inhibits tumor growth in several mouse models.

Cxcr7 gene conservation throughout evolution and the affinity of CXCR7 for CXCL12 suggest that Cxcr7 may also play a role in lymphopoiesis or embryogenesis. The present study reports on the characterization of Cxcr7−/− mice or mice conditionally deficient for Cxcr7 in the endothelium. We show that Cxcr7 is a gene essential for heart valve formation but appears to play no obvious role in hematopoietic or nervous system development. This nonsignaling receptor may mediate some of its effects through heterodimerization with CXCR4, although the significance of this effect in vivo remains unclear.

Results

CXCR7 Is Expressed on a Subset of Mouse and Human B Lymphocytes.

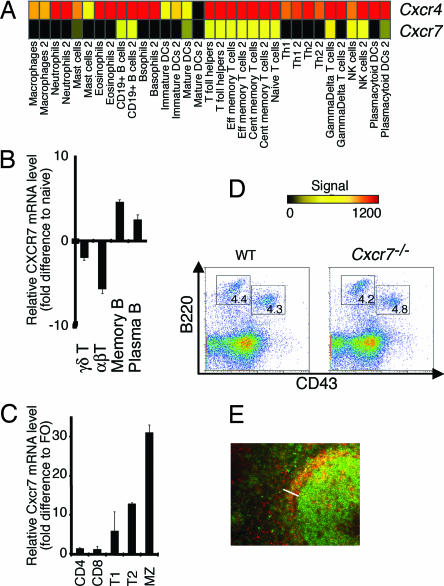

We examined the expression of Cxcr7 using public databases (http://symatlas.gnf.org/SymAtlas) (15) and found that in humans, CXCR7 was expressed in a wide range of tissues. Using a large data set of Affymetrix Genechip expression analyses of human immune cells (16, 17), we found that, within the immune system, Cxcr7 transcripts were present in only a restricted subset of leukocytes, some T cell subsets, and NK cells, as well as in B cells (Fig. 1A). Cxcr7 transcripts were mostly expressed in B cells (Fig. 1 A–C) at high levels, particularly in the human memory B cell subset (Fig. 1B), as reported (18), in mouse splenic marginal zone (MZ) B cells and in transitional type 2 MZ precursors (Fig. 1C). This expression pattern was different from that of the other CXCL12 receptor, CXCR4, suggesting distinct roles in the immune system.

Fig. 1.

Cxcr7−/− mice develop a normal immune system. (A) CXCR7 and CXCR4 expression patterns in human resting leukocyte subsets. The color scale indicates transcript signal where black = absent, yellow = moderately expressed, and red = highly expressed. Cxcr7 mRNA levels quantitated by real-time PCR in human (B) and murine (C) T and B cells relative to naive or follicular (FO) B cells, respectively. Values ± SEM. (D) E17.5 fetal liver cells were stained with antibodies against B220 and CD43. Flow cytometry enumerations were performed within lymphocyte scatter gates. Percentages of cells in the marked gates are indicated. (E) Histological analysis of adult Cxcr7−/− spleen. Sections were stained with antibodies against B220 (green) and CD1d (red). The splenic MZ is indicated (bar)..

Normal Hematopoiesis, CNS, and Gastrointestinal Vasculature in Cxcr7−/− Mice and Modest Reduction in MZ B Cell Numbers.

To dissect the role of Cxcr7 in development and/or immune responses, we generated Cxcr7-deficient mice using a conditional approach [supporting information (SI) Fig. 6 A–C] and noted rapid postnatal death of >95% of Cxcr7−/− neonates within 24 h (SI Fig. 6D). Development of B cells and granulocytes in fetal liver and bone marrow was normal (Fig. 1D and SI Fig. 7), in contrast to findings reported for Cxcl12−/− or Cxcr4−/− mice (3). Analysis of spleens of two surviving adult Cxcr7−/− mice revealed a modest but consistent reduction in the MZ B cell population that nonetheless localized normally to the splenic MZ (Fig. 1E). This was confirmed in Mx1-Cre/+Cxcr7lox/lox mice, in which CXCR7 deletion is induced after polyI:C injection (19) (not shown). Moreover, in contrast to Cxcl12−/− or Cxcr4−/− mice, neural development of Cxcr7−/− mice was indistinguishable from that of WT mice (SI Fig. 8), in keeping with normal levels of Cxcr4 expression in the CNS (SI Fig. 9), as well as gastrointestinal vascularization (SI Fig. 10). Therefore, CXCR7 does not mediate CXCL12-driven hematopoietic functions and appears to be essential neither for MZ B cell localization to the splenic MZ nor for CXCL12-mediated functions in neural and gastrointestinal vasculature development.

Abnormal Heart Valve Development in Cxcr7−/− Mice.

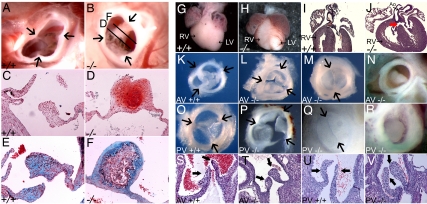

Sudden death of one of the five surviving Cxcr7−/− adult mice revealed the presence of a severely calcified aortic valve (not shown). In another two surviving Cxcr7−/− adults, aortic valve leaflets were thickened and in one of them fused, with clear evidence of chondrification (Fig. 2 A–F). Similar phenotypes were also observed in 10% of adult Cxcr7+/− mice. In 80% of Cxcr7−/− neonates, the heart was abnormal with dilatation of the right ventricle (Fig. 2 G and H). Submembranous ventricular septal defects were detected in 50% of Cxcr7−/− mice, with an associated overriding aorta in some cases (SI Table 1 and Fig. 2 I and J). Atrial septal defects were also observed (SI Table 1). All Cxcr7−/− mice showed a defect in at least one of the semilunar valves (SLVs) (SI Table 1 and Fig. 2 K–V). More than 90% of Cxcr7−/− neonates had an anomalous pulmonary valve, most of the time tricuspid with obviously thickened leaflets (77% of cases; compare Fig. 2 O and P), sometimes bicuspid (10%, Fig. 2Q), and very occasionally obstructed by an overgrown leaflet (5%, Fig. 2R). A similar range of anomalies was detected in the aortic valve of 70% of Cxcr7−/− neonates (Fig. 2 K–N, SI Table 1). Histological analysis confirmed these findings (Fig. 2 S–V). Embryonic hearts did not show any difference in outflow tract and atrioventricular cushion structure until E17.5 (not shown), suggesting that the early steps of cushion formation were not affected. We never observed anomalies of septation between the aorta and pulmonary artery. In addition, the tricuspid and mitral valves appeared normal at all stages examined (SI Fig. 11 A–H).

Fig. 2.

SLV dysmorphogenesis in Cxcr7−/− mice. Adult aortic valve from control; (A, C, and E) and Cxcr7−/− (B, D, and F) mice. Arrows indicate leaflet boundaries. (A and B) Supravalvular view. Planes of sections shown in D and F are indicated. (C–F) Sections through the valves presented in A and B. (C and D) Safranin O staining; red indicates proteoglycans and glucosaminoglycans. (E and F) Movat pentachrome staining; blue indicates proteoglycans. Neonatal phenotype: (G and H) Dissected control and Cxcr7−/− (−/−) hearts. Right ventricle (RV) is often dilated in Cxcr7−/− mice. (I and J) Haematoxylin/eosin-counterstained sections of control and Cxcr7−/− hearts. Membranous ventricular septal defects (VSD, red arrow) and sometimes overriding aorta can be seen in mutants. Dissected aortic (K–N) and Pulmonary (O–R) valves from control and Cxcr7−/− neonates. Arrows indicate leaflet boundaries. Control aortic (K) and pulmonary (O) valves. (L–M, P–R): Phenotypical alterations in mutant valves ranging from thickening, with occasional fusion of valve leaflets (L and P), to formation of a bicuspid valve (M and Q), to obstruction of the valve by an overgrown leaflet (N and R). (S–V) Sections through the neonatal aortic (S and T) or pulmonary (U and V) valves of control (S and U) or Cxcr7−/− (T and V) mice. Black arrows point to valve leaflets. AV, aortic valve; PV, pulmonary valve; LV, left ventricle; Ao, aorta.

Cxcr7 Is Expressed in Cardiac Microvessels, and Specific Cxcr7 Deletion in the Endothelium Recapitulates the Heart Defects Seen in Cxcr7−/− Mice.

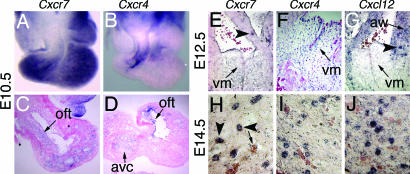

Examination of Cxcr7 expression during embryogenesis, using in situ hybridization (ISH), revealed Cxcr7 transcripts in the endothelial layer of the forming heart from E9.5 (Fig. 3 A and C). At this stage, strong expression was also detected in the neural tube, the brain, and the septum transversum (not shown). At E12.5, Cxcr7 expression was detected in the mesenchyme of the forming valves as well as in numerous microvessels in the myocardium (Fig. 3E). From E14.5 onward, expression could no longer be detected in the mesenchyme, and Cxcr7 was transcribed mainly in the microvasculature associated with myocardium, valves, and great vessels (Fig. 3H). Cxcr4 transcripts were specific to the endothelium of valve-forming regions and their corresponding mesenchyme at E10.5, significantly overlapping with that of Cxcr7 in the outflow tract (Fig. 3 B and D). From E12.5, Cxcr4 and Cxcr7 were expressed in a very similar manner, with diminishing levels of transcripts in valve mesenchyme and strong expression in the microvasculature of the developing valves and myocardium (Fig. 3 E, F, H, and I). At the same stages, expression of Cxcl12 was undetectable in valve primordia but abundant in the aorta walls and myocardium-associated microvasculature (Fig. 3 G and J). Expression of Cxcr4 and Cxcl12 in embryos at various stages was comparable between WT and Cxcr7−/− mice (data not shown). In conclusion, in the developing heart, Cxcl12, Cxcr4, and Cxcr7 are expressed in the myocardial microvasculature, whereas only Cxcr4 and Cxcr7 were transcribed in the valve mesenchyme and associated microvasculature.

Fig. 3.

Expression of Cxcr7, Cxcr4, and Cxcl12 during heart embryogenesis. ISHs with probes specific to Cxcr7 (A, C, E, and H), Cxcr4 (B, D, F, and I), and Cxcl12 (G and J). (A and B) Dissected E10.5 hearts. (C and D) Sections through endothelial cushions of A and B. (E–G) Sections throughout SLVs of E12.5 embryos. (H–J) Sections through myocardium of E14.5 embryos. Avc, atrioventricular canal; Oft; the ouflow tract points; Vm, valve mesenchyme. Arrowheads point to microvasculature; the arrow in H points to unstained coronary vessel.

We specifically deleted the Cxcr7 gene in endothelium using Tie2-Cre transgenic mice (20). Forty percent of Tie2-Cre/+ Cxcr7lox/lox neonates were born with defects in SLVs, similar to those observed in Cxcr7−/− mice (SI Table 1), thus confirming the endothelial origin of the SLV defect in Cxcr7−/− mice. The lower penetration observed in Tie2-Cre/+ Cxcr7lox/lox mice was likely due to incomplete deletion of Cxcr7 by the Tie2-Cre transgene, and indeed residual expression of Cxcr7 was detected in hearts of nonaffected Tie2-Cre/+ Cxcr7lox/lox pups by ISH (not shown).

Impaired Expression of the Angiogenic Factor Hbegf and the Vasculo-Protector Adrenomedullin in Cxcr7−/− Cardiac Valves.

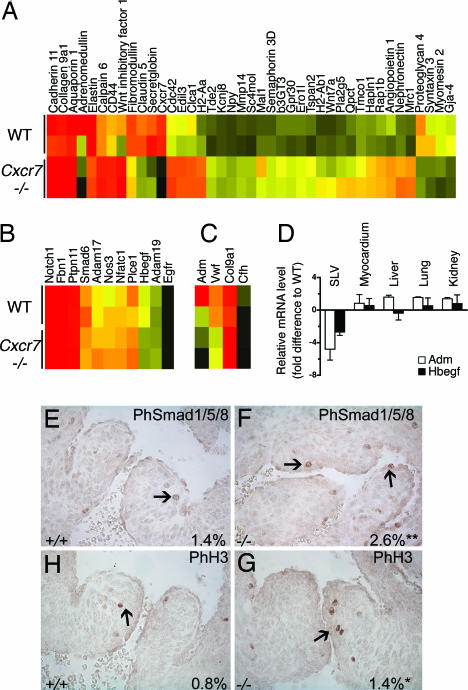

We performed Affymetrix gene profiling on WT and Cxcr7−/− neonatal SLV leaflets. The abnormal remodeling of Cxcr7−/− heart valves shown in Fig. 2 K–V was highlighted by alterations of expression of extracellular matrix components such as Eln, Fmod, Col9a1, Col14a1, and Mmp14 (Fig. 4A). Recently, SLV dysmorphogenesis has been associated with mutations of Notch1 (21), eNos (Nos3) (22), Phospholipase Cε1 (Plce1) (23), Nfatc1 (24), Fibrillin1 (Fbn1) (25), Adam19 (26), Smad6 (27), and various members of the HB-EGF pathway (Hbegf, Egfr, Adam17, and Ptpn11) (28–32). Transcript levels of most of these genes, assessed by ISH (SI Table 2) and/or on gene chips (Fig. 4B) were similar in WT and Cxcr7−/− valves at birth and during embryogenesis. However, expression of Hbegf was down-regulated 2- to 4-fold in neonatal Cxcr7−/− SLVs, which we confirmed by quantitative PCR (Fig. 4D). Other organs, including the myocardium, retained normal levels of expression (Fig. 4D). Valve thickening in Hbegf−/− mice is associated with increased bone morphogenetic protein signaling and proliferation in valve cells at midgestation (30). We observed similar effects in Cxcr7−/− heart valves (Fig. 4 E–H). Gene profiling of Cxcr7−/− SLV leaflets also revealed a dramatic reduction in expression of Adrenomedullin (Adm) compared with controls (Fig. 4C). In addition, expression of some genes linked to the function of Adm, such as complement factor H (Cfh), von Willebrand factor (Vwf), and Col9a1 (33), were also significantly altered in Cxcr7−/− SLVs (Fig. 4C). Adm expression was unaffected in other neonatal Cxcr7−/− tissues tested (Fig. 4D). Therefore, down-regulation of Adm, like Hbegf, appeared not to be a general defect but rather restricted to SLV leaflets. Valve microvessels cells could not be isolated from leaflets in numbers high enough for culture. This precluded any attempt to demonstrate ex vivo modulation of Hbegf and Adm expression in response to CXCL12 or CXCL11. We have tested other systems of cultured endothelial cells and could not show modulation of these two genes in response to CXCL12 or CXCL11 (data not shown). This suggests either that modulation of Hbegf and Adm expression is either an indirect consequence of Cxcr7 deletion, or that CXCR7-dependent expression of these genes is restricted to the developing valve leaflets.

Fig. 4.

Gene profiling of neonatal Cxcr7−/− SLVs. Heat maps of ECM and adhesion genes differentially expressed in WT and Cxcr7−/− dissected SLV leaflets (A), genes associated with SLV defects (B), and genes linked to Adm function (C). Signal intensity is color-coded (A–C). (D) qRT-PCR analysis of Hbegf and Adm expression in various control and Cxcr7−/− neonatal organs. Values ± SEM. (E–H) PhosphoSmad1/5/8 or phosphohistone H3 immunohistological staining on sections of E14.5 control (+/+) and Cxcr7−/− (−/−) SLVs. Percentage of positive nuclei in SLVs per staining and genotype are indicated. *, P < 0.01; **, P < 0.001.

CXCL12 and CXCL11 Are the Only Two Chemokine Ligands of CXCR7.

SLVs develop normally in Cxcl12−/− mice (4), suggesting that a ligand distinct from CXCL12 may be involved in CXCR7 function in valve morphogenesis (18). We tested the ability of a range of chemokines to compete with 125I-CXCL12 binding to human CXCR7 transfectants (SI Fig. 12A). Only CXCL12 (SDF-1) and CXCL11 (ITAC) could displace 125I-CXCL12 binding, and CXCL11 was not as efficient as cold CXCL12 (SI Fig. 12B), similar to recently published findings (8, 9). However, alignment of the Cxcl11 sequence from various mouse strains showed that C57BL/6, the genetic background of Cxcr7−/− mice are natural null mutants for Cxcl11 (SI Fig. 12C), because a 2-bp insertion soon after the start codon of the C57BL/6 sequence creates a frameshift resulting in a premature stop codon. Because C57BL/6 mice develop normally in the absence of a functional copy of Cxcl11, CXCL11/CXCR7 interaction is unlikely to play a nonredundant role in SLV formation.

CXCR7 and CXCR4 Form Heterodimers, Potentiating Signaling in Response to CXCL12.

We and others (9) have failed to detect calcium flux or migratory behavior of CXCR7-expressing cells after stimulation with CXCL12 or CXCL11. Moreover, the DRYLAIV motif conserved in most chemokine receptors and considered necessary for G protein coupling and calcium signaling (34) is altered to DRYLSIT in CXCR7. Thus CXCR7 may not function as a classical chemokine receptor but could behave as a decoy or chemokine-transporting receptor, similar to other endothelial-expressed receptors such as D6, CCX-CKR, and DARC (34). An alternative explanation is that CXCR7 may not function alone but may modulate CXCR4 functions via formation of heterodimeric complexes as shown for other chemokine receptors (35–37), although the importance of this phenomenon in vivo is not known. We tested this hypothesis using FRET, a technique that allows temporal and spatial resolution of heterodimeric complexes.

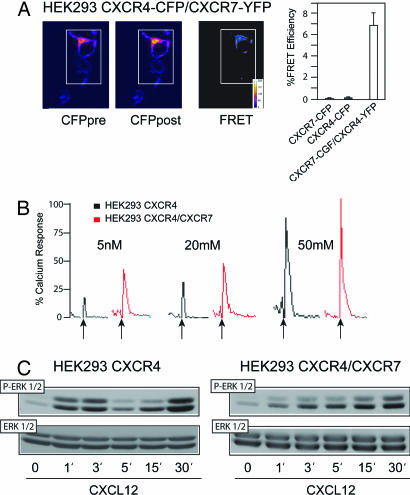

HEK293 cells transiently transfected with CXCR4–cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) and CXCR7–yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) were used for FRET analysis. Preformed dimers of CXCR4 and CXCR7 were detected at the cell membrane in the absence of ligand, with evidence also of intracellular heterodimer pools (Fig. 5A). Immunoprecipitation experiments using HEK293 cells (which endogenously express CXCR4), CXCR7-stably transfected HEK293 cells, or IM-9 cells that naturally express CXCR4 and low levels of CXCR7 (SI Fig. 13 A–D), in the presence or absence of CXCL12, confirmed the presence of CXCR7/CXCR4 heterodimers in the absence of ligand in both cell lines (SI Fig. 13 A and D).

Fig. 5.

CXCR4 and CXCR7 form functional heterodimers. (A) FRET measurements in unstimulated HEK293 cells transiently transfected with CXCR4-CFP and CXCR7-YFP. CFP emission before (CFPpre) and after YFP bleaching (CFPpost) and a false-color merged image (FRET) are shown. Data are expressed as percentage of FRET efficiency ± SD. (B) Representative Ca2+ flux triggered by CXCL12 on HEK293 cells expressing both CXCR7 and CXCR4 or only-CXCR4. Results are expressed as a percentage of the maximum chemokine-induced Ca2+ response. (C) Anti-phospho-ERK immunoblot after CXCL12 stimulation of HEK293 or CXCR7-transfected HEK293. Protein loading was controlled with an anti-ERK antibody.

Chemokine receptor heterodimerization increases the sensitivity and dynamic range of the chemokine response (35). We evaluated CXCL12-induced Ca2+ flux in both HEK293 and CXCR7-stably transfected HEK293 cells. Addition of CXCL12 induced a stronger Ca2+ flux in cells coexpressing CXCR4 and CXCR7 than in control (CXCR4 only) cells (Fig. 5B). Chemokines trigger MAPK activation (38, 39), and heterodimers can activate signaling pathways that differ from those activated by homodimers (35). We evaluated whether coexpression of CXCR7 could affect CXCL12-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation via CXCR4 using stably transfected HEK293 cells. Whereas a biphasic activation of ERK was detected in cells that express CXCR4 only, with peaks at 3 and 30 min, in cells coexpressing CXCR4 and CXCR7, CXCL12 induced a delayed peak of ERK activation without the initial spike (Fig. 5C and SI Fig. 13E). In conclusion, CXCR4/CXCR7 form heterodimers, and coexpression of these two receptors induces a stronger Ca2+ flux than CXCR4 alone and modulates downstream signaling through ERK1/2.

Discussion

CXCR7 is a highly conserved chemokine receptor that binds with high affinity to the chemokine CXCL12. Similar to the other CXCL12 receptor CXCR4, CXCR7 is widely expressed and plays a role in fetal development. Cxcr7−/− mice showed atrial septal defects and submembranous ventricular septal defects as well as impaired SLV remodeling but to date no obvious immune or brain phenotype.

Endothelial-specific inactivation using Tie2-Cre mice recapitulated Cxcr7−/− mice phenotype, supporting a predominant role for CXCR7 in endothelial biology.

We observed a dramatic phenotype in Cxcr7−/− mice, despite this receptor showing no apparent signaling to its ligand CXCL12. A possible explanation is that CXCR7 forms heterodimers with CXCR4 and modulates CXCR4 signaling to CXCL12. In the heart, Cxcr7 expression only significantly overlaps with Cxcr4 expression in the valve-forming regions, the outflow tract mesenchyme in particular, and later in the microvasculature. Therefore, heterodimerization of the corresponding proteins at these sites could be required for proper valve morphogenesis. Recent findings indicate that many G protein-coupled seven-transmembrane receptors, including chemokine receptors, exist as homo- and heterodimers, and that these conformations may be important in aspects of receptor biology that range from ontogeny to regulation of pharmacological and signaling properties (37, 40, 41). At the immunological synapse, CXCR4/CCR5 heterodimers recruit the Gαq subunit (rather than the Gαi) and induce costimulatory signals to T cells (36). Indeed, heterodimerization and associated effects on signaling may be one mechanism that accounts for the widespread expression of nonsignaling chemokine receptors in endothelium (34). Nevertheless, the significance of chemokine receptor heterodimerization in vivo remains uncertain. The phenotypic differences described for Cxcr7−/− (reported here) and Cxcr4−/− mice (3, 5–7), and recent work examining the role of these receptors in zebrafish development (42, 43), support an alternative hypothesis, that CXCR7 and CXCR4 can have separate biological roles.

A recent study showed that CXCR7 facilitated angiogenesis, and blockade of CXCR7 inhibited tumor growth in mouse models (9). We did not observe any gross difference in the density of the microvasculature in Cxcr7−/− mice; however, deficiency of Cxcr7 correlated with down-regulation of at least two endothelial-expressed angiogenic genes in neonatal valves, Hbegf and Adm. Mutations in components of the HB-EGF pathway lead to increased bone morphogenetic protein signaling and proliferation, associated with valve thickening (27, 30, 32, 44). Similar alterations were observed in Cxcr7−/− SLVs, suggesting that the valve phenotype of Cxcr7−/− mice stems in part from partial down-regulation of Hbegf. By ISH, expression patterns of Hbegf and Cxcr7 were very similar at midgestation, and conditional inactivation of Hbegf using Tie2Cre recapitulated the valve defects found in embryos homozygous for the full null allele (31). However, more Hbegf−/− mice survive (40%) than Cxcr7−/− mice (30), implying other alterations contributing to the phenotype in Cxcr7−/− mice. We observed a marked down-regulation of Adm at birth, a known vasculoprotector critical for embryonic development (45). Adm expression was unaffected in all other tissues tested, and it is unclear whether its down-regulation in SLVs was a cause or a consequence of the observed heart valve phenotype. Combined down-regulation of both Hbegf and Adm might trigger a severe impairment of SLV function, and potentially the early lethality observed Cxcr7−/− mice.

SLVs develop normally in Cxcl12−/− mice (4), suggesting that a ligand distinct from CXCL12 may be involved in CXCR7 function in valve morphogenesis. However, because Cxcl12−/− mice were generated on a mixed 129xC57BL/6 background and express CXCL11, we cannot exclude a compensatory signaling role for CXCL11 via CXCR7 in these mice. Furthermore, because C57BL/6 mice develop normally in the absence of a functional copy of Cxcl11, CXCL11/CXCR7 interaction is unlikely to play a nonredundant role in SLV formation. Therefore, although CXCL12 and CXCL11 may normally be functionally redundant, there may also be an as-yet-unidentified ligand for CXCR7 involved in valve morphogenesis.

The phenotypes of mice lacking Cxcl12, Cxcr4, or Cxcr7 highlight the essential role of certain chemokines and receptors in embryonic development. It is conceivable that the original evolutionary function of chemokine receptors was to serve as guidance molecules during embryonic or fetal development, and CXCL12 binding to CXCR4 has a clear role in such processes (1). The immune system may have adopted, duplicated, and refined certain receptors specifically for immune cell migration. Our results reveal distinct roles for the two CXCL12 receptors, CXCR7 and CXCR4. CXCR7 plays an important role in cardiac development and further studies are needed to determine the precise connection between this role and its role in tumor angiogenesis (9). Regardless, study of the role of CXCR7 through gene deletion has provided insight into heart valve morphogenesis, which ultimately may have relevance for the identification of additional factors that contribute to heart valve defects in humans.

Materials and Methods

Generation of Cxcr7lox/+ Mice.

Cxcr7lox/+ mice were generated at Ozgene (Bentley DC, Australia). Briefly, LoxP sites were inserted around exon 2, which encodes CXCR7, in C57BL/6 Cxcr7 genomic DNA. Bruce 4 C57BL/6 ES cells were electroporated. Chimeric males generated with Cxcr7lox/+ ES cells were mated to C57BL/6J females to obtain Cxcr7lox/+ mice. Cxcr7lox/+ mice were crossed to C57BL/6 CMV-Cre (46) or C57BL/6 Tie2-Cre/+ transgenic mice (20) to generate germ-line or endothelial-specific deletion of Cxcr7 (SI Fig. 6). All experimental procedures involving mice were carried out according to protocols approved by the Garvan Institute /St. Vincent's Hospital Animal Ethics Committee and the Animal Resources Center/Ozgene Animal Ethics Committee.

Immunohistochemistry and Cytochemistry.

Immunohistochemistry and cytochemistry were performed after fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde and wax embedding. Anti-PhosphoSmad1/5/8 (9511S; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) and PhosphoHistone H3 (06-570; Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY) were applied after an antigen retrieval step in citrate buffer for 8 min at subboiling temperature. At least three sections across each SLV of two controls and two mutants were counted (>2,000 cells per genotype). Statistical analysis was done using a χ2 test. Cytochemistry for chloroacetyl esterase was done on paraffin-embedded sections of femurs from E17.5 embryos using an esterase activity staining kit (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), following the manufacturer's protocol. Ten-micrometer sections were stained with a Russell-Movat pentachrome stain kit (American Master Tech Scientific, Lodi, CA) following the manufacturer's protocol. Other sections were stained with Safranin O.

RNA Extraction, GeneChip Hybridization, and Gene Profile Analysis.

Affymetrix 430 2.0 GeneChips were hybridized with cRNA synthesized from RNA from neonate SLVs dissected under the microscope. Two different pools of WT and mutant SLV RNAs were used in independent hybridizations. cRNA was prepared, and GeneChips were hybridized and scanned as previously described (16). Analysis of gene profiles is described in more detail in SI Text.

qRT-PCR.

cDNA was synthesized from 100 ng of total RNA using Reverse-IT RTase Blend Kit (Abgene, Surrey, U.K.), following the manufacturer's indications. Quantitation was performed on at least three independent WT and Cxcr7−/− samples for each tissue analyzed, and experiments were carried out in triplicate. β-actin was used to standardize the total amount of cDNA. Primer sequences can be found in SI Table 3.

ISH.

ISH was performed by using a conventional protocol (see SI Text). Probe templates were amplified by using primers described in SI Table 3 and verified by sequencing.

FRET.

FRET was measured by photobleaching of HEK293 cells (American Type Culture Collection TIB202) transiently transfected at a 1:1 ratio with CXCR4-CFP and CXCR7-YFP and cultured in coverslip chambers (Nunc, Rochester, NY) for 48 h. Identical results were obtained with CXCR7-CFP and CXCR4-YFP. Cells were imaged by using a laser-scanning confocal microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan; IX81). HEK293 cells transfected with CXCR4-CFP and CXCR7-CFP were used as negative controls. Data are reported as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was tested by using the unpaired Student's t test. Detailed description of a typical FRET experiment is available in SI Text.

Western Blot.

A 20 nM concentration of CXCL12-stimulated HEK293 cells or CXCR7 stably transfected HEK293 cells or IM-9 cells (2 × 107) were lysed in 20 mM triethanolamine (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 20% glycerol, 2% digitonin, 10 mM sodium orthovanadate, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 μg/ml aprotinin for 30 min at 4°C and then centrifuged (15,000 × g, 15 min, 4°C) and processed for Western blot with anti-phospho-ERK1/2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA).

Calcium Determination.

Untransfected or CXCR7-stably transfected HEK293 cells (2.5 × 106 cells/ml) were resuspended in RPMI medium 1640 containing 10% FCS and 10 mM Hepes and incubated with Fluo-3 (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA). Cells were washed, resuspended in RPMI containing 2 mM CaCl2, and maintained at 4°C before adding CXCL12. Calcium flux was measured at 525 nm in an EPICS XL flow cytometer (Coulter, Hialeah, FL).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank O. Prall, M. Costa, M. Furtado, S. Liu, J. Zaunders, and R. Bouveret for comments on the manuscript and R. G. Graham for helpful discussions. This work is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia), the Wellcome Trust (U.K.), and the NSW Cancer Research Institute.

Abbreviations

- SLV

semilunar valve

- ISH

in situ hybridization

- En

embryonic day n

- MZ

marginal zone

- CFP

cyan fluorescent protein

- YFP

yellow fluorescent protein.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo (accession no. GSE8710).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0702229104/DC1.

References

- 1.Doitsidou M, Reichman-Fried M, Stebler J, Koprunner M, Dorries J, Meyer D, Esguerra CV, Leung T, Raz E. Cell. 2002;111:647–659. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01135-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mackay CR. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:95–101. doi: 10.1038/84298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zou YR, Kottmann AH, Kuroda M, Taniuchi I, Littman DR. Nature. 1998;393:595–599. doi: 10.1038/31269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nagasawa T, Hirota S, Tachibana K, Takakura N, Nishikawa S, Kitamura Y, Yoshida N, Kikutani H, Kishimoto T. Nature. 1996;382:635–638. doi: 10.1038/382635a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma Q, Jones D, Borghesani PR, Segal RA, Nagasawa T, Kishimoto T, Bronson RT, Springer TA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9448–9453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bagri A, Gurney T, He X, Zou YR, Littman DR, Tessier-Lavigne M, Pleasure SJ. Development (Cambridge, UK) 2002;129:4249–4260. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.18.4249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu M, Grove EA, Miller RJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:7090–7095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092013799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balabanian K, Lagane B, Infantino S, Chow KY, Harriague J, Moepps B, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Thelen M, Bachelerie F. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:35760–35766. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508234200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burns JM, Summers BC, Wang Y, Melikian A, Berahovich R, Miao Z, Penfold ME, Sunshine MJ, Littman DR, Kuo CJ, et al. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2201–2213. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heesen M, Berman MA, Charest A, Housman D, Gerard C, Dorf ME. Immunogenetics. 1998;47:364–370. doi: 10.1007/s002510050371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Broberg K, Zhang M, Strombeck B, Isaksson M, Nilsson M, Mertens F, Mandahl N, Panagopoulos I. Int J Oncol. 2002;21:321–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burger JA, Kipps TJ. Blood. 2006;107:1761–1767. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Busillo JM, Benovic JL. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1768:952–963. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salcedo R, Oppenheim JJ. Microcirculation. 2003;10:359–370. doi: 10.1038/sj.mn.7800200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Su AI, Cooke MP, Ching KA, Hakak Y, Walker JR, Wiltshire T, Orth AP, Vega RG, Sapinoso LM, Moqrich A, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:4465–4470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012025199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chtanova T, Newton R, Liu SM, Weininger L, Young TR, Silva DG, Bertoni F, Rinaldi A, Chappaz S, Sallusto F, et al. J Immunol. 2005;175:7837–7847. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.12.7837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu SM, Xavier R, Good KL, Chtanova T, Newton R, Sisavanh M, Zimmer S, Deng C, Silva DG, Frost MJ, et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118:496–503. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Infantino S, Moepps B, Thelen M. J Immunol. 2006;176:2197–2207. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuhn R, Schwenk F, Aguet M, Rajewsky K. Science. 1995;269:1427–1429. doi: 10.1126/science.7660125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koni PA, Joshi SK, Temann UA, Olson D, Burkly L, Flavell RA. J Exp Med. 2001;193:741–754. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.6.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garg V, Muth AN, Ransom JF, Schluterman MK, Barnes R, King IN, Grossfeld PD, Srivastava D. Nature. 2005;437:270–274. doi: 10.1038/nature03940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee TC, Zhao YD, Courtman DW, Stewart DJ. Circulation. 2000;101:2345–2348. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.20.2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tadano M, Edamatsu H, Minamisawa S, Yokoyama U, Ishikawa Y, Suzuki N, Saito H, Wu D, Masago-Toda M, Yamawaki-Kataoka Y, et al. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:2191–2199. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.6.2191-2199.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de la Pompa JL, Timmerman LA, Takimoto H, Yoshida H, Elia AJ, Samper E, Potter J, Wakeham A, Marengere L, Langille BL, et al. Nature. 1998;392:182–186. doi: 10.1038/32419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pyeritz RE. Annu Rev Med. 2000;51:481–510. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.51.1.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou HM, Weskamp G, Chesneau V, Sahin U, Vortkamp A, Horiuchi K, Chiusaroli R, Hahn R, Wilkes D, Fisher P, et al. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:96–104. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.1.96-104.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Galvin KM, Donovan MJ, Lynch CA, Meyer RI, Paul RJ, Lorenz JN, Fairchild-Huntress V, Dixon KL, Dunmore JH, Gimbrone MA, Jr, et al. Nat Genet. 2000;24:171–174. doi: 10.1038/72835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iwamoto R, Yamazaki S, Asakura M, Takashima S, Hasuwa H, Miyado K, Adachi S, Kitakaze M, Hashimoto K, Raab G, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:3221–3226. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0537588100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iwamoto R, Mekada E. Cell Struct Funct. 2006;31:1–14. doi: 10.1247/csf.31.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jackson LF, Qiu TH, Sunnarborg SW, Chang A, Zhang C, Patterson C, Lee DC. EMBO J. 2003;22:2704–2716. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nanba D, Kinugasa Y, Morimoto C, Koizumi M, Yamamura H, Takahashi K, Takakura N, Mekada E, Hashimoto K, Higashiyama S. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;350:315–321. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.09.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen B, Bronson RT, Klaman LD, Hampton TG, Wang JF, Green PJ, Magnuson T, Douglas PS, Morgan JP, Neel BG. Nat Genet. 2000;24:296–299. doi: 10.1038/73528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garcia-Unzueta MT, Berrazueta JR, Pesquera C, Obaya S, Fernandez MD, Sedano C, Amado JA. J Diabetes Compl. 2005;19:147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haraldsen G, Rot A. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:1659–1661. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mellado M, Rodriguez-Frade JM, Vila-Coro AJ, Fernandez S, Martin de Ana A, Jones DR, Toran JL, Martinez AC. EMBO J. 2001;20:2497–2507. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.10.2497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Molon B, Gri G, Bettella M, Gomez-Mouton C, Lanzavecchia A, Martinez AC, Manes S, Viola A. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:465–471. doi: 10.1038/ni1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Percherancier Y, Berchiche YA, Slight I, Volkmer-Engert R, Tamamura H, Fujii N, Bouvier M, Heveker N. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:9895–9903. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411151200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ganju RK, Brubaker SA, Meyer J, Dutt P, Yang Y, Qin S, Newman W, Groopman JE. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:23169–23175. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.36.23169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thelen M. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:129–134. doi: 10.1038/84224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Babcock GJ, Farzan M, Sodroski J. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:3378–3385. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210140200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Terrillon S, Bouvier M. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:30–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Valentin G, Haas P, Gilmour D. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1026–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dambly-Chaudiere C, Cubedo N, Ghysen A. BMC Dev Biol. 2007;7:23–37. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-7-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Choi M, Stottmann RW, Yang YP, Meyers EN, Klingensmith J. Circ Res. 2007;100:220–228. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000257780.60484.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shimosawa T, Shibagaki Y, Ishibashi K, Kitamura K, Kangawa K, Kato S, Ando K, Fujita T. Circulation. 2002;105:106–111. doi: 10.1161/hc0102.101399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schwenk F, Baron U, Rajewsky K. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:5080–5081. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.24.5080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.