Abstract

P815A is a naturally occurring tumor rejection Ag of the methylcholanthrene-induced murine mastocytoma P815. The gene encoding the Ag P815A, designated P1A, is identical to that encoded in the normal genome of the DBA/2 mouse. A recombinant vaccinia virus (rVV) was constructed that expressed a synthetic oligonucleotide encoding the minimal determinant peptide of the tumor-associated Ag. Although the rVV recombinant expressing this mini-gene was recognized efficiently in vitro, it was an ineffective immunogen in vivo. The addition of an endoplasmic reticulum insertion signal sequence to the NH2 terminus of the minimal determinant resulted in a rVV that elicited CD8+ T cells that could lyse P815 mastocytoma cells in vitro and that were therapeutic in vivo. Recombinant viruses expressing synthetic oligonucleotide sequences preceded by the insertion signal sequences allow the expression of Ag directly into the endoplasmic reticulum, where binding to MHC class I molecules is most efficient. Vaccines based on synthetic oligonucleotides could be constructed with ease and rapidity but, most importantly, such constructs avoid the dangers associated with the expression of full length genes encoding TAA that are potentially oncogenic.

CD8+ CTL (TCD8+)3 clearly play an important role in anti-neoplastic immunity (1, 2). TCD8+have shown to reside in the tumor mass (3) and can destroy autologous tumor in vitro and in vivo (4-6). TCD8+ recognize peptides 8 to 10 amino acids in length, complexed with MHC class I molecules (7, 8). The peptide fragments recognized by TCD8+ are generated primarily in the cytosol and are transported into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), the site of association with class I molecules, mainly by a specialized heterodimer called TAP (transporter associated with antigen processing) (9). An alternate, TAP-independent pathway for entry into the ER is via ER insertion signal sequences, located at the 5′ ends of mRNAs that target peptidesfor co-translational insertion into the ER, or at the NH2, termini of precursor peptides (10-13).

Ags involved in the process of malignant transformation (including oncogene products and mutated tumor suppressor gene products) are of potential use in the development of recombinant vaccine strategies (14-19). Recombinant vaccinia viruses, a vehicle for the expression of TAA, intracellularly express large quantities of the inserted gene products within the cytoplasm of infected cells and thus target host Ag-processing pathways (20). Vaccination with recombinant virus has been shown to induce Ag-specific cellular and humoral immunity (21, 22), which in one model system resulted in the active treatment of murine tumors bearing human carcinoembyronic antigen (22).

In this work, the murine model of P815 was used to test the potential use of oligonucleotide fragments of tumor-associated Ags in vaccine design. Recently, Van den Eynde et al. cloned the gene P1A using anti-P815 TCD8+ clones generated from mice that rejected immunogenic (tumor negative or tum-) variants of P815 induced by in vitro mutagenesis (23, 24). The P1A gene codes for the P815A and the P815B rejection Ags expressed by the P815 tumor. The P1A gene is identical in sequence to the normal gene encoded by DB/2 mice and is expressed by atleast one unrelated, syngeneic mast cell line; thus, it represents a non mutated “self” Ag recognized by anti-tumor T cells (23, 24). A minimal antigenic peptide (P815A35–43) has been determined corresponding to amino acid residues 35–43 presented in the context of H-2Ld. We demonstrate here that synthetic oligonucleotides, encoding peptides presented by class I molecules and produced by recombinant vaccinia viruses, can also elicit powerful anti-tumor TCD8+.

Materials and Methods

Tumors and animals

P815 is a mastocytoma cell line of H-2d haplotype (ATCC, TIB64) of DBAI2 origin. CT-26 (H-2d) is a N-nitroso-methylurethane-induced murine colon tumor line, donated by D. Pardoll (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD). L-Ld and L-Kd are L cells (H-2k) transfected with Ld or Kd, respectively (donated by J. Seidman, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA). The EL4 (H-2b) thymoma was a kind gift of M. Bevan (University of Washington, Seattle, WA). T2 cells expressing the H-2 Ld or H-2 Kb molecules, respectively, were a gift of P. Cresswell (Yale, New Haven, CT). All tumor cell lines were cultured in complete medium (CM) containing RPMI 1640, 10% heat-inactivated FCS (both from Biofluids, Rockville, MD), 0.03% fresh glutamine, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 100 U/ml penicillin (all from National Institutes of Health media unit), and 50 μg/ml gentamicin. Female DBA/2 mice, 6 to 10 wk old, were obtained from the Frederick Cancer Research Facility, National Institutes of Health (Frederick, MD).

Viruses

Recombinant vaccinia virus (rVV) stocks, derived from the WR strain were produced using the thymidine kinase-deficient human osteosarcoma 143/B cell line (ATCC CRL 8303; American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD). A rVV expressing a Kd-restricted epitope of influenza A/PR/8/34 (PR8) nucleoprotein (rVV-NPM147–155) and the 147–155 epitope preceded by the adenovirus type 5 E3/19K gene product (rVV-ESNP147–155) have been described (25). rVV expressing the full length native P815A protein (rVV-P815A) were developed from a plasmid containing the cDNA for the P815A Ag kindly provided by T. Boon (Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, Brussels, Belgium). In brief, P1A was cut out of the pGEM-4Z plasmid (24) with kpn 1 and cloned into the same site of the pSCl1 plasmid (kindly provided by B. Moss, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Bethesda, MD). rVV producing a natural Ld-restricted P815A tumor Ag determinant preceded by an initiating methionine (rVV-P815AM35–43) was constructed with the following synthetic double-stranded oligonucleotide (TCG ACC ACC ATG CTG CCT TAT CTA GGG TGG CTG GTC TTC TGA TAG GTA CCG C) and (GG TGG TAC GAC GGA ATA GAT CCC ACC GAC CAG AAG ACT ATC CAT GGC GCC GG) into the vaccinia virus genome, also using the pSC11 plasmid in a manner described for the other recombinants (25). rVV expressing the P815A35–43 minimal determinant preceded by the E3/19K leader sequence (MRYMILGLLALAAVCSA), rVV-ESP815A35–43 was constructed in a similar manner to the rVV-ESNP147–155 (25) using the double-stranded synthetic oligonucleotide corresponding to the P815A35–43 peptide (G GCC CTG CCT TAT CTA GGG TGG CTG GTC TTC TGA TAG GTA CC) and (GAC GGA ATA GAT CCC ACC GAC CAG AAG ACT ATC CAT GGG TTC). Note that in the latter two cases, the synthetic oligonucleotides were constructed to contain Kozak’s consensus sequence (CCACC) preceding the ATG-initiating methionine (26) for translation. rVV-P815AM35–43 was constructed by inserting the corresponding synthetic double-stranded oligonucleotide. Oligonucleotides were synthesized on a 392 DNA synthesizer and purified over an oligonucleotide purification cartridge (both from Applied Biosystems, (ABI), Foster City, CA).

Peptides

Synthetic peptides corresponding to residues 35–43 of the P815A protein (LPYLGWLVF) and residues 147–155 of PR8 NP (TYQRTRALV) were synthesized and HPLC-purified (>99%) by Peptide Technologies (Washington, DC).

Generation of effector cells

Anti-tumor TCD8+ populations were generated from DBN/2 mice by i.v. injection of 5 × 106 plaque-forming units (PFU) of recombinant vaccinia virus as described previously (27). Three- to eight weeks after vaccination, splenocytes were dispersed using stainless steel mesh screens and cultured in T-75 flasks (Nunc Maxi Corp., Roskilde, Denmark), in the absence of IL-2, with 1 μg/ml of the appropriate synthetic peptide at a final concentration of 3 × 106 splenocytes/ml in CM containing 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and 2.5 × 10−5 M 2-ME. Six days later, splenocytes were washed three times before use in a 51Cr release assay. For adoptive immunotherapy treatments, RBC were lysed with ACK hypotonic lysing buffer (from National Institutes of Health media unit, Bethesda, MD) and washed extensively with HBSS.

51Cr release assays

Six- or eight-hour 51Cr release assays were performed as described previously (27). In brief, 2 × 106 tumor targets in 0.3 ml of CM were labeled with 200 μCi 51Cr for 90 min. Con A blasts were made by culturing fresh splenocytes from DBA/2 mice at a concentration of 2 × 106/ml and 3.75 μg/ml Con A in CM for 3 days before testing. Peptide-pulsed cells were incubated with 1 μM synthetic peptide P815A35–43 or NP147–155 during labeling. Target cells were then mixed with effector cells for 6 or 8 h at 37°C at the E:T ratios indicated. CT-26, T2-Kd or T2-Ld cells were infected for 2 h at 37°C with rVV at 10 PFU/cell as described previously (27). The amount of 51Cr released was determined by gamma counting, and the percent specific lysis was calculated as follows: [(experimental cpm − spontaneous cpm)/(maximal cpm − spontaneous cpm)] × 100.

Adoptive immunotherapy

Five or six DBA/2 mice per group were injected i.p. with P815 tumor (104) in 0.5 ml of HBSS. Three days later, tumor-bearing mice were irradiated (500 rad) as described previously (28), then treated on days 3 and 6 with an i.p. injection of either anti-P815A- or anti-NP-specific effector cells at 2 × 107 cells/dose. Specifically, for the generation of the effector cells, mice were immunized i.v. with 5 × 106 PFU of either rVV-ESP815A35–43 or rVV-ESNP147–155 Three weeks later, splenocytes were harvested and cultured for 6 days with either 1 μg/ml P815A35–43 or 1μg/ml NP147–155 synthetic peptides, respectively. Where indicated, mice received 7500 U of rhIL-2 twice daily for 3 days. Survival of the mice was then monitored over time.

Results and Discussion

Characterization of rVV expressing the P815A peptide

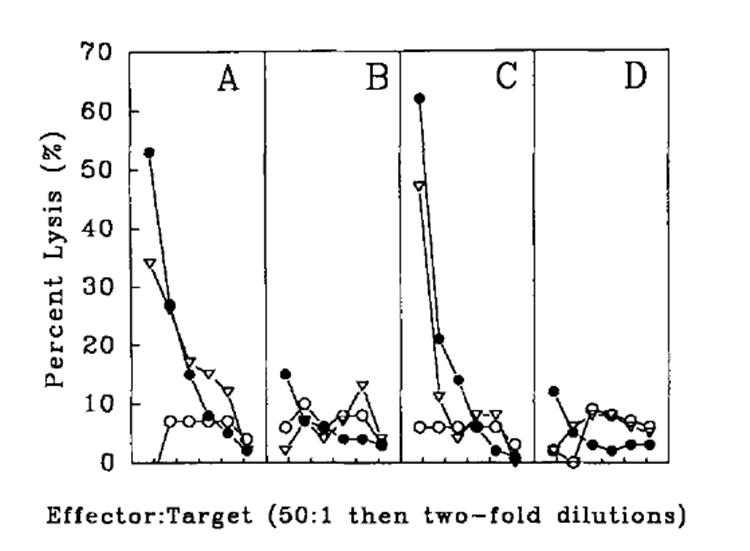

To study the possible use of rVV-expressing synthetic oligonucleotides, immunization of mice with rVV expressing an Ld-restricted peptide epitope (LPYLGWLVF) of P815A preceded by an initiating methionine (rVV-P815AM35–43) was compared with a rVV expressing the full length P815A Ag (rVV-P815A). As shown in Figure lA, mice immunized with rVV-P815A developed TCD8+ lytic responses specific for P815. In contrast, rVV-P815AM35–43 did not prime mice efficiently for TCD8+ responses against the P815 mastocytoma or against the H-2d target cellline CT-26 pulsed with P815A35–43 peptide (Fig. 1B). In only 5 of 16 experiments did the rVV-P815AM35–43 elicit splenocytes capable of lysing P815 or of syngeneic cells pulsed with P815A35–43 peptide at levels greater than background (>10% at an E:T ratio of 50:1). In the absence of in vitro stimulation with peptide, day 6 primary anti-P815A TCD8+ responses were not observed, even though all groups consistently developed anti-vaccinia lytic responses (data not shown). By contrast, anti-vaccinia responses would not be expected in secondary cultures, because in vitro stimulation was with peptide alone.

FIGURE 1.

Anti-tumor responses elicited by immunization with the minimal determinant rVV-ESP815A35–43 construct. DBA/2 mice were immunized i.v. with 5 × 106 PFU of rVVP815A (A), rVV-P815AM35–43 (B), rVV-ESP815A35–43 (C), or rVV-NPM147–155 (D). Three weeks later, splenocytes were restimulated in vitro with 1 μg/ml synthetic peptide, P815A35–43, for 6 days and then assayed for specific TCD8+ activity in a 51Cr release assay against CT-26 (○), P815 (●), and CT-26 pulsed with P815A35–43 minimal peptide (△) target cells.

A possible explanation for the finding that the immunogenicity of rVV-P815AM35–43 was severely compromised is that the P815AM35–43 minimal peptide was susceptible to cytoplasmic proteases. Alternatively, the peptide produced by the rVV-P815AM35–43 could have been sequestered inthe cytosol because of either altered trafficking or failure to be transported by TAP. Finally, we considered the possibility that the initiating methionine, encoded for by the necessary ATG start codon, was not cleaved off by Metamino peptidase, and thus compromised the ability of the peptide to bind to the Ld molecule. When the constructs were tested in vitro, however, the rVV expressing the minimal determinant P815AM35–43 was shown to functionally process and present the P815AM35–43 peptide on the cell surface better than the rVV expressing the full length protein (Table I).

Table I.

Lysis of CT-26 targets infected with rVVa

| Targets | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT-26infected with: | ||||||

| E:T | P815 | CT-26 | rVV

P815A |

rVV-

P815AM35–43 |

rVV-

ESP815A35–43 |

rVV

NPM147–155 |

| (% Specific 51Cr Released)a | ||||||

| 100:1 | 47 | 7 | 30 | 87 | 79 | 10 |

| 50:1 | 35 | 7 | 31 | 79 | 74 | 12 |

| 25:1 | 23 | 6 | 25 | 64 | 61 | 9 |

| 12:1 | 12 | 3 | 13 | 50 | 42 | 7 |

| 6:1 | 7 | 3 | 9 | 29 | 24 | 3 |

| 3:1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 20 | 11 | 1 |

CT-26 cells were infected with the rvv indicated as decribed in Materials and Methods. The abilities of designated rVV to produce and present P815A35–43 was tested om a 51Cr release assay at the E:T ratios shown. Anti-P815A effectors were generated by immunizing DBA/2 with 5 × 106 PFU i.v. of rVV-ESP815A35–43, and 21 days later splenocytes were restimulated in vitro with 1 μg/ml P81535–43 sythetic petide for 6 days. Values shown represent means of triplicates. The experiment was repeated with similar results.

The data shown in Table I, however, are not necessarily inconsistent with those shown in Figure 1, because critical differences could exist in the function of vaccinia in vivo and in vitro. Furthermore, the in vitro test that was performed measures the expression of the P815A determinant induced by the recombinant vaccine on an infected target cell (part of the efferent immune response), where as the in vivo test is a measure of the recombinant vaccine’s ability to prime lymphocytes (part of the afferent limb of the immune response). Because it is not known exactly what APCs are functioning in the in vivo priming, it is difficult to address the mechanisms of the failure of the minimal determinant construct to prime.

Addition of a leader sequence to the P815A peptide enhances immunogenicity

A rVV was constructed that expressed an ER insertion signal sequence at the 5′ end or NH2 terminus of the minimal determinant (rVV-ESP815A35–43). The addition of the signal sequence was hypothesized to potentially salvage the minimal determinant rVV by increasing the concentration of peptide in the ER lumen, the site of peptide association with class I molecules via two potential mechanisms. The first is that the nascent polypeptide would be expressed directly into the smaller volume of the ER, and would not be subject to the inefficiencies of TAP, because signal sequence translocation is TAP-independent. Second, the addition of a signal sequence may enable the peptide to avoid the proteolytic environment of the cytosol. As shown in Figure lC, splenocytes from mice immunized with rVV-ESP815A35–43 mediated lysis of P815 tumor cells that bear the P815A epitope, as well as CT-26, a P815A Ag-negative cell line, when pulsed with P815A147–155 peptide. A control virus, rVV-ESNP147–155, failed to prime a lytic response against the P815A tumor Ag (Fig. 1D). Surprisingly, in 4 of 4 experiments the reactivity observed with rVV-ESP815A35–43 was equivalent to or better than that induced by rVV-P815A.

It is not clear what the rules are for the efficient induction of TCD8+ immune responses (Restifo et al., accepted for publication). In some Ag systems, OVA for example, full length proteins were as immunogenic as either the minimal determinant alone or preceded by a leader sequence. In the influenza nucleoprotein Ag system, primary TCD8+ responses were only induced by peptides or peptides targeted to the ER and not the full length protein. In every case, however, the addition of a leader sequence never reduced lytic responses and, in some cases, enhanced the lytic responses that were observed. Alternative leader sequences may also function to target proteins to the ER. For example, in the NP system, the addition of the IFN signal sequence preceding the minimal determinant also demonstrated primary TCD8+ responses that were equivalent to those obtained with the adenovirus leader sequence.

rVV-ESP815A35–43 is TAP-independent and elicits TCD8+ that are Ld-restricted

Potential TAP independence was examined by infecting Ld-transfected T2 cells with rVV-ESP815A35–43. T2 cells (30) lack a 1-mega base pair fragment of the MHC class II region, a region that contains TAP (31). As shown in Table II, both CT-26 cells and T2-Ld cells were lysed by anti-P815A effector cells when pulsed with peptide. The rVV-P815AM35–43 failed to confer lysis upon infection of T2-Ld cells, whereas it did function efficiently in the TAP-intact CT-26 cell line in the same experiment. rVV-ESP815A35–43 did efficiently confer lysability on T2-Ld cells, indicating that the peptide was presented by a TAP-independent mechanism.

Table II.

rVV-ESP815A35–43 confer lysability onto target cells in a TAP-independent fashion

| Target Cell | ||

|---|---|---|

| Target Cell Treatment | CT-26 | T-2 transfected with Ld |

| (% Specific 51Cr Released at E:T of 50:1/12:1)a | ||

| Alone | −1/2 | 5/2 |

| Pulsed with P815A35–43 | 33/28 | 26/18 |

| Infected with rVV-P815AM35–43 | 40/24 | 9/6 |

| Infected with rVV-ESP815A35–43 | 38/21 | 34/16 |

| Infected with rVV-ESNP147–155 | 3/7 | 8/7 |

aAnti-P815A effectors were generated by immunizing DBA/2 mice with 5 × 106 PFU i.v. of rVV-ESP815A35–43. Sixty days later, splenocytes were restimulated in vitro with 1 μg/ml P815A35–43 synthetic peptide for 6 days. Note that killing of P815 cells in the experiment shown was 33/29. Values shown represent the means of triplicates. The experiment was repeated with similar results.

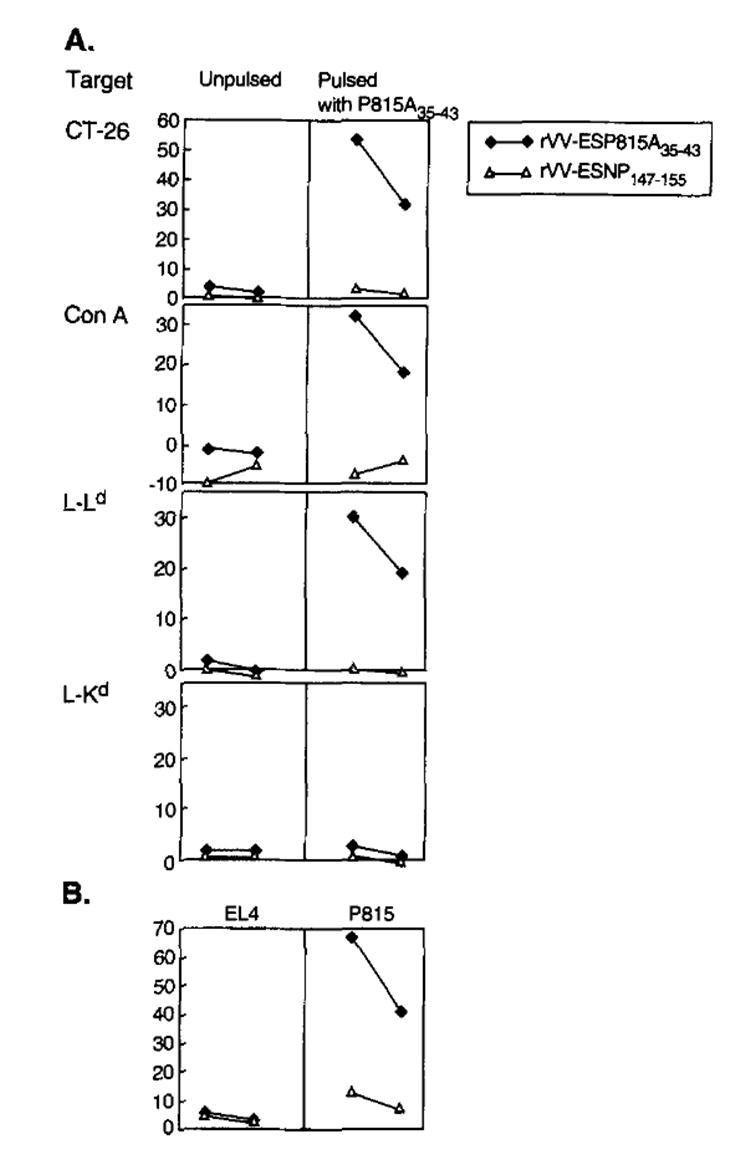

To determine whether the TCD8+ cells elicited by rVV-ESP815A35–43 were actually recognizing the P815A35–43 peptide presented by the Ld molecule, and whether the observed responses could be elicited by a rVV expressing a leader sequence preceding an irrelevant peptide, we characterized the TCD8+more carefully. As shown in Figure 2, the specificity of the response was determined by testing rVV-ESP815A35–43- and rVV-ESNP147–155-derived effectors against a variety of targets. The rVV-ESP815A35–43 effectors were specific for the P815A35–43 peptide when exogenously pulsed onto CT-26 cells or onto syngeneic Con A blasts. MHC restriction analysis, performed using L cell transfectants, showed that although Ld transfectants were lysed, Kd transfectants were not. Identically treated effector cells derived from mice immunized with rVV-ESNP147–155 and stimulated in vitro with P8l5A35–43 peptide in the same experiment failed to recognize P815 or targets pulsed exogenously with P81535–43 peptide. In addition, the response was unlikely to represent NK or LAK activity because neither the unpulsed CT-26 cells nor the allogeneic EL4 thymoma cells (H-2b) were lysed (Fig. 2, A and B). Finally, the response was not only specific for the P815A35–43 peptide when exogenously pulsed on the surface of tumor cells, but also for the peptide when endogenously expressed, processed, and presented by the P815 tumor (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

The anti-tumor response elicited by immunization with rVV-ESP815A35–43 is specific for theP815A35–43 peptide presented in the context of Ld. DBA/2 mice were immunized with 5 × 106 PFU of either rVV-ESP815A35–43 or rVV-ESNP147–155. Three weeks later, splenocytes were restimdated in vitro with 1 μg/ml synthetic peptide, P815A35–43 and then assayed for specific lytic activity at E:T ratios of 50:1 and 25:1 in a 51Cr release assay against CT-26, Con A-treated blasts (Con A), L cells transfected with H-2-Ld (L-Ld), or L cells transfected with Kd (L-Kd) either unpulsed or pulsed with the P815A35–43 synthetic peptide (A). The same effector cells were assayed for lytic activity against EL4 thymoma (H-2b) and P815 mastocytoma (H-2d) (B).

In vivo anti-tumor efficacy of anti-P815A35–43 effector cells

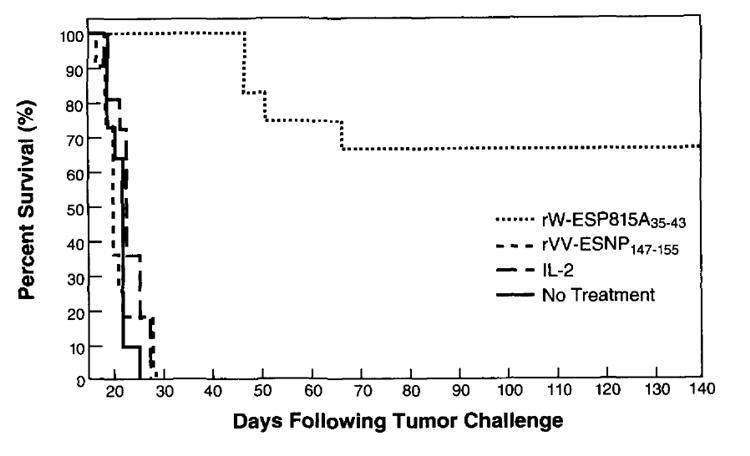

To determine whether rVV-ESP815A35–43-elicited TCD8+ were therapeutically effective in mice with established tumor, 104 P815 mastocytoma cells were given to mice i.p. 3 days before the start of treatment. The adoptive transfer of two doses of anti-P815A-specific TCD8+ effectors on day 3 and day 6 resulted in a prolongation of survival compared with mice treated in the same manner with control effector TCD8+ cells reactive with the NP147–155 peptide in the context of H-2-Kd (p = 0.0001) (Fig. 3). Note that in both cases mice received IL-2. Tumor-bearing mice that were given IL-2 alone, or mice that were given no treatment at all, were dead by day 30. Mice challenged with 104 P815 cells that received only one dose of 2 × 107 anti-P815A effector cells on day 3 also demonstrated 74% survival after 130 days (data not shown). In experiments where mice were challenged with 104 P815 tumor cells and treated adoptively with anti-P815A effector cells on day 6, no increase in survival was observed compared with the control groups (not shown). Furthermore, active immunotherapy of cancer using these constructs did not reduce the rate of tumor growth (data not shown).

FIGURE 3.

Adoptive treatment of P815 tumor-bearing mice with anti-P815A-specific CTL induced byrVV-ESP81535–43. On day 0, DBA/2 mice were challenged with 104 P815 tumor cells i.p. The mice received i.p. treatments on day 3 and day 6 with 2 × 107 anti-P815A effector cells plus IL-2, 2 × 107 anti-NP147–155 secondary effector cells plus IL-2, IL-2 alone, or no treatment. For the generation of effector cells, mice were injected i.v. with either rVV-ESP815A35–43 or rVV-ESNP147–155 as described. Three weeks later, splenocytes were cultured with the appropriate peptide (1 μg/ml) for 6 days. Mice received IL-2 i.p. (7500 U) twice daily for 3 days. The figure represents a combination of two independent experiments, each with five to six mice per group.

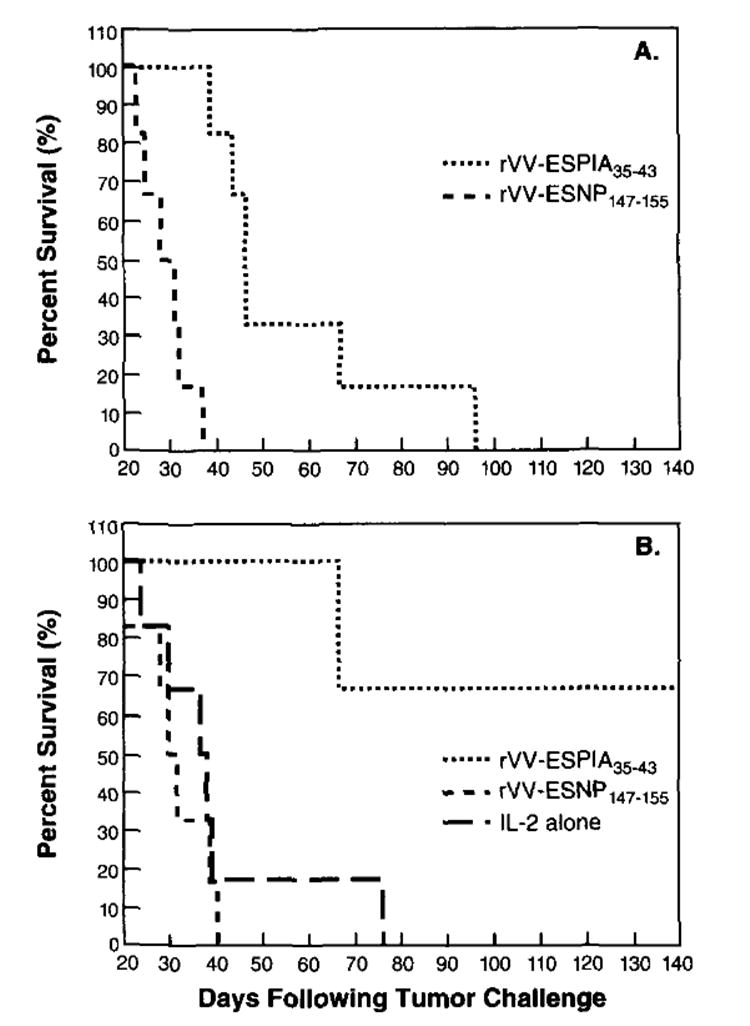

To determine whether the administration of IL-2 was important to observe therapeutic effects of the rVV-ESP815A35–43-induced effector cells, tumor-bearing animals were treated on day 3 with P815A35–43-specific effectors either with or without IL-2. As shown in Figure 4A, the anti-P815A35–43 TCD8+ administered without IL-2 were able to increase the lifespan of mice bearing the P815 tumor as compared with mice that received the control anti-NP147–155 cells (p = 0.0006). A significant enhancement in survival rate was observed (Fig. 4B) in the group of mice that received the anti-P815A effectors followed by IL-2 administration as compared with anti-P815A effector cell treatment alone (p = 0.003) (Fig. 4A). Most importantly, 67% of the mice were long-term survivors, having then survived >200 days.

FIGURE 4.

The administration of IL-2 prolongs survival of mice receiving adoptive treatment with anti-P815A-specific TCD8+. DBA/2 mice (6/group) were challenged with 104 P815 tumor cells i.p. Three days later, in the same experiment, mice were treated i.p. with 2 × 107 anti-P815A35–43 effector cells or 2 × 107 anti-NP147–155 effector cells generated as described in the legend of Figure 3 without (A) or with (B) IL-2. A control group of mice that received IL-2 alone was also included. IL-2 was administered i.p. (7500 U) twice daily for 3 days. The figure shows a representative experiment of two independent experiments performed.

Thus, we demonstrate here that a recombinant viral vector expressing a synthetic oligonucleotide sequence encoding a single determinant can elicit therapeutic TCD8+ against a tumor. Furthermore, the mouse model chosen uses an antigenic determinant that, like many of the recently cloned human tumor Ags, is nonmutated from that encoded in the genome of normal, nontransformed cells (24). Use of minimal determinant constructs may have the advantage of avoiding the potential dangers of overexpression proteins of unknown function that could be potential oncogenes or in a situation, like p53, in which a variety of mutations can exist (32). This approach also allows one to immunize against one specific epitope, thus eliminating the possible induction of cross-reactive autoimmune responses against epitopes found in closely related proteins, such as those observed in the carcinoembyronic antigen family (33).

Previous work has shown that the addition of the identical leader sequence to the minimal determinant of P815A (H-2Ld) peptide emulsified in CFA could also induce P815A-specific TCD8+ (13). Peptide immunization is attractive in that it may be safer than viral immunization and may avoid the problems of diminished immune responses observed in patients previously immunized against smallpox. However, vaccinia virus is far more efficient at producing high quantities of Ag in the cytoplasm (20), the origin of antigenic peptides in most cell lines that have been studied thus far (9). Most importantly, the rVV constructs consistently yield specific TCD8+ responses that are more potent than those induced with peptide immunization.

In this study, using vaccinia virus as an expression vector, the additional strategy of linking an ER insertion signal sequence preceding the peptide had a distinct advantage over the minimal peptide alone. Immunization with rVV-expressing peptides preceded by a leader sequence may be clinically useful for the treatment of patients with melanoma, a disease in which many Ags recognized by TCD8+ are being characterized (14, 34-39). rVV could be used in vivo to increase precursor frequencies in PBL or in tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes for subsequent restimulation in vitro with peptides. This approach is consistent with the kinetics of tumor growth in humans because generally there isadequate time for the in vivo and in vitro maturation and expansion of anti-tumor T lymphocytes (5, 6). A rVV encoding the minimal peptide for the melanoma Ag MAGE-1 (39) preceded by an ER insertion signal sequence has been constructed and is currently being tested in human clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jon Yewdell and Jack Bennink for critically important ideas, for reading the manuscript, and for valuable reagents. We also thank Igor Bačík, Akash Taggarse, and Mike Nishimura for the creation of the rVV, and Dave Jones, Beth Palmer, and Judy Stephens for technical assistance.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- TCD8+

CT8+ CTL

- rVV

recombinant vaccinia virus

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- CM

complete medium

- PFU

plaque forming units

References

- 1.Greenberg PD, Cheever MA, Fefer A. H-2 restriction of adoptive immunotherapy of advanced tumors. J Immunol. 1981;126:2100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Itoh K, Platsoucas DC, Balch CM. Autologous tumor-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in the infiltrate of human metastatic melanomas: activation by interleukin-2 and autologous tumor cells and involvement of the T cell receptor. J Exp Med. 1988;168:1419. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.4.1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Topalian SL, Solomon D, Rosenberg SA. Tumor-specific cytolysis by lymphocytes infiltrating human melanomas. J Immunol. 1989;142:3714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muul LM, Spiess PJ, Director EP, Rosenberg SA. Identification of specific cytolytic immune responses against autologous tumor in humans bearing malignant melanoma. J Immunol. 1987;138:989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenberg PD. Adoptive T cell therapy of tumors: mechanisms operative in the recognition and elimination of tumor cells. Adv Immunol. 1991;49:281. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60778-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenberg SA, Yannelli JR, Yang JC, Topalian SL, Schartzentruber DJ, Weber JS, Parkinson DR, Seipp CA, Einborn JH, White DE. Treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma with autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and interleukin-2. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:1159. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.15.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Townsend AM, Rothbard J, Gotch FM, Bahdur G, Wraith D, McMichael AJ. The epitopes of influenza nucleoprotein recognized by cytotoxic T lymphocytes can be defined with short synthetic peptides. Cell. 1986;44:959. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90019-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Townsend A, Bodmer H. Antigen recognition by class I-restricted T lymphocytes. Annu Rev Immunol. 1989;7:601. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.003125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yewdell JW, Bennink JR. Cell biology of antigen processing and presentation to major histocompatibility complex class I molecule-restricted T lymphocytes. Adv Immunol. 1992;52:1. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60875-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartmann E, Sommer T, Prehn S, Gorlicb D, Jentsch S, Rapoport TA. Evolutionary conservation of components of the protein translocation complex. Nature. 1994;367:654. doi: 10.1038/367654a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson K, Cresswell P, Gammon M, Hermes J, Williamson A, Zweerink H. Endogenously synthesized peptide with an endoplasmic reticulum signal sequence sensitizes antigen-processing mutant cells to class I-restricted cell-mediated lysis. J Exp Med. 1991;174:489. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.2.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bacik I, Cox JH, Anderson R, Yewdell JW, Bennink JR. TAP (transporter associated with antigen processing)-independent presentation of endogenously synthesized peptides is enhanced by endoplasmic reticulum insertion sequences located at the amino-but not carboxyl-terminus of the peptide. J Immunol. 1994;152:381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Minev BR, McFarland BJ, Spiess PJ, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. Insertion signal sequence fused to minimal peptides elicits specific CD8+ T cell responses and prolongs survival of thymoma-bearing mice. Cancer Res. 1994;54:4155. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Houghton AN. Cancer antigens: immune recognition of self and altered self. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Disis ML, Smith JW, Murphy AE, Chen W, Cheever MA. In vitro generation of human cytolytic T cells specific for peptides derived from the HER-2/neu protooncogene protein. Cancer Res. 1994;54:1071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peace DJ, Smith JW, Chen W, You SG, Cosand WL, Blake J, Cheever MA. Lysis of ras oncogene-transformed cells by specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes elicited by primary in vitro immunization with mutated ras peptide. J Exp Med. 1994;179:473. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.2.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Houbiers JG, Nijman HW, van der Burg SH, Drijfhout JW, Kenemans P, van de Velde CJ, Brand A, Momburg F, Kast WM, Melief CJ. In vitro induction of human cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses against peptides of mutant and wild-type p53. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:2072. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melief CJ, Kast WM. Potential immunogenicity of oncogene and tumor suppressor gene products. Curr Opin Immunol. 1993;5:709. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(93)90125-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Speiser DE, Kyburz D, Stubi U, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel RM. Discrepancy between in vitro measurable and in vivo virus-neutralizing cytotoxic T cell reactivities. Low T cell receptor specificity and avidity sufficient for in vitro proliferation or cytotoxicity to peptide-coated target cells but not for in vivo protection. J Immunol. 1992;149:972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moss B. Vaccinia virus: a tool for research and vaccine development. Science. 1991;252:1662. doi: 10.1126/science.2047875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Estin CD, Stevenson US, Plowman GD, Hu SL, Sriddar P, Hellstrom I, Brown JP, Hellstrom KE. Recombinant vaccinia virus vaccine against human melanoma antigen p97 for use in immunotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:1052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.4.1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kantor J, Irvine K, Abrams S, Kaufman H, DiPietro J, Schlom J. Antitumor activity and immune responses induced by a recombinant carcinoembryonic antigen-vaccinia virus vaccine. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1992;84:1084. doi: 10.1093/jnci/84.14.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lethe B, Van den Eynde B, Van Pel A, Corradin G, Boon T. Mouse tumor rejection antigens P815A and P815B: two epitopes carried by a single peptide. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:2283. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van den Eynde B, Lethe B, Van Pel A, De Plaen E, Boon T. The gene coding for a major tumor rejection antigen of tumor P815 is identical to the normal gene of syngeneic DBN2 mice. J Exp Med. 1991;173:1373. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.6.1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eisenlohr LC, Bacik I, Bennink JR, Bernstein K, Yewdell JW. Expression of a membrane protease enhances presentation of endogenous antigens to MHC class I-restricted T lymphocytes. Cell. 1992;71:963. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90392-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kozak M. Structural features in eukaryotic mRNAs that modulate the initiation of translation. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:19867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Restifo NP, Esquivel F, Kawakami Y, Yewdell JW, Mule JJ, Rosenberg SA, Bennink JR. Identification of human cancers deficient in antigen processing. J Exp Med. 1993;177:265. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.2.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dye ES, North RJ. T cell-mediated immuno suppression as an obstacle to adoptive immunotherapy of the P815 mastocytoma and its metastases. J Exp Med. 1981;154:1033. doi: 10.1084/jem.154.4.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lawson CM, Bennink JR, Restifo NP, Yewdell JW, Murphy BR. Primary pulmonary cytotoxic T lymphocytes induced by immunization with a vaccinia virus recombinant expressing influenza A virus nucleoprotein peptide do not protect mice against challenge. J Virol. 1994;68:3505. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.6.3505-3511.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Darsley MJ, Takahashi H, Macchi MJ, Frelinger JA, Ozato K, Apella E. New family of exon-shuffled recombinant genes reveals extensive interdomain interactions in class I histocompatibility antigens and identifies residues involved. J Exp Med. 1987;165:211. doi: 10.1084/jem.165.1.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spies T, Cerundolo V, Colonna M, Cresswell P, Townsend A, DeMars R. Presentation of viral antigen by MHC class I molecules is dependent on a putative peptide transporter heterodimer. Nature. 1992;355:644. doi: 10.1038/355644a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yanuck M, Carbone DP, Pendleton CD, Tsukui T, Winter SF, Minna JD, Berzofsky JA. A mutant p53 tumor suppressor protein is a target for peptide-induced CD8+ cytotoxic T cells. Cancer Res. 1993;53:3257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shively J, Beatty J. CEA-related antigens: molecular biology and significance. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 1985;2:355. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(85)80008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kawakami Y, Eliyahu S, Delgado CH, Robbins PF, Rivoltini L, Topalian SL, Miki T, Rosenberg SA. Cloning of the gene coding for a shared human melanoma antigen recognized by autologous T cells infiltrating into tumor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robbins PF, El-Gamil M, Kawakami Y, Rosenberg SA. Recognition of tyrosinase by tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes from a patient responding to immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 1994;54:3124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pardoll DM. Tumour antigens: a new look for the 1990s. Nature. 1994;369:357. doi: 10.1038/369357a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bakker AB, Schreurs MW, de Boer AJ, Kawakami Y, Rosenberg SA, Adema GJ, Figdor CG. Melanocyte lineage-specific antigen gp100 is recognized by melanoma-derived tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1005. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.3.1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cox AL, Skipper J, Chen Y, Henderson RA, Darrow TL, Shabanowitz J, Engelhard VH, Hunt DF, Slingluff CL., Jr Identification of a peptide recognized by five melanoma-specific human cytotoxic T cell lines. Science. 1994;264:716. doi: 10.1126/science.7513441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van der Bruggen P, Traversari C, Chomez P, Lurquin C, De Plaen E, Van den Eynde B, Knuth A, Boon T. A gene encoding an antigen recognized by cytolytic T lymphocytes on a human melanoma. Science. 1991;254:1643. doi: 10.1126/science.1840703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]