Abstract

Some tumor cells express Ags that are potentially recognizable by T lymphocytes and yet do not elicit significant immune responses. To explore new immunotherapeutic strategies aimed at enhancing the recognition of these tumor-associated Ags (TAA), we developed an experimental mouse model consisting of a lethal clone of the BALB/c tumor line CT26 designated CT26.WT, which was transduced with the lacZ gene encoding β-galactosidase, to create CT26.CL25. The growth rate and lethality of CT26.CL25 and CT26.WT were virtually identical despite the expression by CT26.CL25 of the model tumor Ag in vivo. A recombinant fowlpox virus (rFPV), which is replication incompetent in mammalian cells, was constructed that expressed the model TAA, β-galactosidase, under the influence of the 40-kDa vaccinia virus early/late promoter. This recombinant, FPV.bg40k, functioned effectively in vivo as an immunogen, eliciting CD8+ T cells that could effectively lyse CT26.CL25 in vitro. FPV.bg40k protected mice from both subcutaneous and intravenous tumor challenge by CT26.CL25, and most surprisingly, mice bearing established 3-day pulmonary metastasis were found to have significant, Ag-specific decreases in tumor burden and prolonged survival after treatment with the rFPV. These observations constitute the first reported use of rFPV in the prevention and treatment of an experimental cancer and suggest that changing the context in which the immune system encounters a TAA can significantly and therapeutically alter the host immune response against cancer.

The recent cloning, by several independent groups, of tumor associated Ags (TAA)3 recognized by CD8+ T cells (TCD8+) has opened new possibilities for the immunotherapy of cancer (1-7). These newly discovered TAA potentially could be used in the development of recombinant and synthetic anticancer vaccines. Using techniques that are now standard in virology, molecular biology, and synthetic protein chemistry, the immunotherapist now has some measure of control over the quantity and kinetics of TAA expression, the intracellular compartment into which TAA are expressed, and what tissues or cell types are used to express TAA in vivo.

Recombinant poxviruses are attractive candidates for the expression of TAA, because heterologous proteins can be expressed intracellularly, targeting Ag-processing pathways and potentially leading to immune recognition by T lymphocytes (8, 9). Poxviruses are not oncogenic and do not integrate into the host genome. Unlike other eukaryotic DNA viruses, poxviruses replicate and transcribe their genetic material in the cytoplasm and use the host cellular machinery for translation. Poxvirus particles are large, complex, and enveloped and contain a single, linear, double-stranded DNA molecule and enzymes concerned with RNA synthesis, including RNA polymerase, capping and methylating enzymes, and poly(A) polymerase. Host cell transcription factors, thus, are not limiting in the production of heterologous RNA, because they are not required.

Recombinant fowlpox virus (rFPV) is an avipox virus that maintains gene expression but does not productively infect mammalian cells, which makes fowlpox an attractive candidate for a safe and effective recombinant viral vaccine in humans (10, 11). The use of FPV has been largely restricted to the protection of chicken livestock from various pathogens (12, 13). Little is known about its efficacy in immunizing mammals. rFPV expressing a rabies glycoprotein gene was shown to protect mice, cats, and dogs from a lethal rabies challenge (14). Mice were protected against fatal measles encephalitis by immunization with an rFPV expressing the measles virus fusion protein (15).

The present study has evaluated the use of rFPV in anticancer therapy. To the best of our knowledge this is the first reported use of a nonreplicating virus in the prevention and treatment of an experimental cancer. The model TAA used here is β-galactosidase (β-gal), which is encoded by the lacZ gene. β-Gal has been characterized as an Ag in systems investigating Ag localization, immunity to intracellular microorganisms, class I Ag processing, tolerance, and its role as a model tumor marker (16-20). A lethal clone of CT26, an H-2d undifferentiated colon adenocarcinoma of BALB/c origin, was retrovirally transduced to stably express β-gal. Immune responses against the model TAA β-gal were characterized in vivo and in vitro. TCD8+ responses were studied with the use of a 9-amino acid-long peptide fragment of β-gal (TPH PARIGL), which has been shown to be presented by the Ld class I molecule, which enabled the monitoring of specific immunity against this model TAA (21).

Materials and Methods

Retroviral transduction of tumors

CT26 is an N-nitroso-N-methylurethane-induced BALB/c (H-2d) undifferentiated colon carcinoma kindly provided by D. Pardoll (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD) (22). CT26 was cloned to generate CT 26. WT (cloning was done to minimize antigenic heterogeneity). To stably transduce CT26.WT with the gene for lacZ, a retrovirus was used. Plasmid LZSN (a kind gift from A.D. Miller, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle, WA) contains the β-gal gene in the retroviral LXSN vector (23). The retroviral backbone was derived from the Moloney murine leukemia virus and contained the lacZ gene under the transcriptional control of the long-terminal repeat from the Moloney murine leukemia virus, whereas the SV40 promoter controls the expression of the neomycin resistance gene. To generate the retroviral packaging line, 30 μg of LZSN DNA were used to CaPO4 transfect a mixture of 2 × 105 PA317 amphotropic packaging line (also provided by A. D. Miller) cells (24) and 3 × 105 GP + E 86 ecotropic packaging line cells (25). Four days after transfection, the packaging cells were split to a low density to isolate the faster-growing PA317 cells and selected in the neomycin analog Geneticin (G418; GIBCO BRL Laboratories, Gaithersburg, MD). Hightiter G418-resistant PA317 clones were then selected to recreate the packing cell line PA-LZ and used for gene transfer into tumor. PA-LZ was grown to 75% confluence, at which time media not containing G418 were exchanged, and the cells were grown for 16 h before the supernatant was harvested. Retroviral supernatant was then added to a 75% confluent flask of CT 26.WT and incubated in the presence of 10 μg/ml polybrene. After 24 h the media were replaced with culture medium containing 400 μg/ml G418 for 1 wk. Transductants were then subcloned by limiting dilution at 0.3 cells per well. Subclones that stably expressed β-gal were evaluated by β-gal staining, and their susceptibility to lysis by anti-β-gal effectors was tested in 51Cr release assays. The subclone CT26.CL25 was selected for use in all in vitro and in vivo studies because of its stable high expression of both β-gal and the class I molecule H-2 Ld.

The DBA/2 mastocytoma P815 (H-2d) and P13.1, which is a clone of P815 that stably expresses β-gal (kindly provided by Y. Paterson, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA), were used as targets in 51Cr release assays. As a negative control for 51Cr release assays, the cell line E22 (kindly provided by Y. Paterson), a clone of the mouse thymoma EL4 stably transfected with lacZ, was used. Cell lines were maintained in RPMI 1640, 10% heat-inactivated FCS (Biofluids, Rockville, MD), 0.03% l-glutamine, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 100 μg/ml penicillin, and 50 μg/ml gentamicin sulfate (National Institutes of Health Media Center, Bethesda, MD). CT26.CL 25, P13.1, and E22 were maintained in the presence of 400 μg/ml G418 (Life Technologies, Inc., Grand Island, NY).

Recombinant fowlpox and vaccinia viruses

The POXVAC-TC (Schering Corp.) strain of FPV was used in these studies. FPV was propagated on primary chick embryo dermal cultures (26). Foreign sequences were inserted into FPV by homologous recombination as previously described (26) by workers at Therion Biologics, Inc. Recombinant FPV.bg40k contains the Escherichia coli lacZ gene under the control of the vaccinia virus 40-kDa promoter (designed H6 in Ref. 27), inserted into the BamHI J region of the FPV genome to generate FPV.bg40k.

Recombinant vaccinia virus (rVV) stocks were produced using the thymidine kinase-deficient human osteosarcoma 143/B cell line (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD; CRL 8303). rVVs expressing β-gal and influenza virus A/PR/8/34 nucleoprotein (NP)were constructed by previously described methods (28, 29). In the HPV16-E6Vac, lacZ was under the control of the natural VV P7.5 early/late promoter from plasmid pJS6 (all kindly provided by B. Moss, NIAID, NIH, Bethesda, MD), and the control CR19 vaccinia virus (also designated wild-type vaccinia, because it is not a recombinant) was kindly provided by J. Yewdell and J. Bennink (NIAID, NM, Bethesda, MD). Prototype construction of rVV has been described (29). HPV16-E6Vac was constructed by homologous recombination into the thymidine kinase locus and propagated in human osteosarcoma 143/B cells (American Type Culture Collection; CRL 8303) and used as crude cell lysates. Crude 19 is a nonrecombinant control vaccinia virus from which the recombinants were constructed.

Peptides

The synthetic peptide TPHPARIGL, representing the naturally processed H-2 Ld restricted epitope spanning amino acids 876 to 884 of β-gal (21), was synthesized by Peptide Technologies (Washington, DC) to a purity of greater than 99% as assessed by HPLC and amino acid analysis.

Effector cells

Female BALB/c mice, 8 to 12 wk old, were obtained from the Animal Production Colonies, Frederick Cancer Research Facility, National Institutes of Health (Frederick, MD). Primary lymphocyte populations were generated by injecting BALB/c mice i.v. with 107 plaque-forming units (PFU) of rFV.bg40k. To assay for primary in vivo responses, spleens were harvested on day 6, dispersed into a single cell suspension, and tested for their ability to lyse β-gal-expressing and control targets in a 6-h 51Cr release assay. Secondary in vitro effector populations were generated by harvesting the spleens of mice 21 days after immunization with recombinant virus and culturing single cell suspensions of splenocytes in T-75 flasks (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) at a density of 5.0 × 106 splenocytes/ml with 1 μg/ml antigenic peptide in a total volume of 30 ml of culture medium consisting of RPMI 1640 with 10% FCS (from Biofluids) that contained 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids, 1.0 mM sodium pyruvate (both from Biofluids) and 5 × 10−5 M 2-ME (GIBCO BRL, Rockville, MD) in the absence of IL-2. Seven days later, splenocytes were harvested and washed in culture medium before testing in a 51Cr release assay.

51Cr release assay

Six-hour 51Cr release assays were performed as previously described (30). Briefly, 2 × 106 target cells were incubated with 200 mCi of Na51CrO4 (51Cr) for 90 min. Peptide-pulsed CT26.WT were incubated with 1 μg/ml (which is roughly 1 μM) antigenic peptide during labeling as previously described (31). Target cells were then mixed with effector cells for 6 h at the effector-to-target ratios indicated. The amount of 51Cr released was determined by γ counting, and the percent specific lysis was calculated from triplicate samplesas follows: [(experimental cpm − spontaneous cpm)/(maximal cpm − spontaneous cpm)] × 100. Data included in this report represent assays in which spontaneous release was less than 10% of maximal release, and SD of triplicate values were all less than 5%.

In vivo protection and treatment studies

For in vivo protection studies, mice were immunized with either FPV.bg40k or FPV.WT 21 days before an s.c. challenge with 104 tumor cells or an i.v. challenge with 5 × 105 tumor cells, as previously described (32). After tumor challenge, all mice were randomized. Mice receiving s.c. tumors were measured twice a week. When tumors developed, they all grew progressively and were lethal. Mice were killed, however, when they were moribund. All mice that seemed to be long-term survivors had no palpable tumors. Mice receiving i.v. administered tumors were killed on day 12 and randomized before counting lung metastases in a blinded fashion as previously described (33).

For in vivo treatment studies, unirradiated BALB/c mice were challenged with either 105 or 5 × 105 tumor cells i.v. to establish pulmonary metastases. Mice were subsequently vaccinated with 107 PFU of the designated FPV i.v. on days 3 or 6. Mice involved in multiple-immunization protocols received second i.v. vaccinations 3 or 7 days after the first. Metastatic lung nodules were enumerated in a randomized and blinded manner. Identically treated mice were followed for long-term survival and killed when moribund.

Results

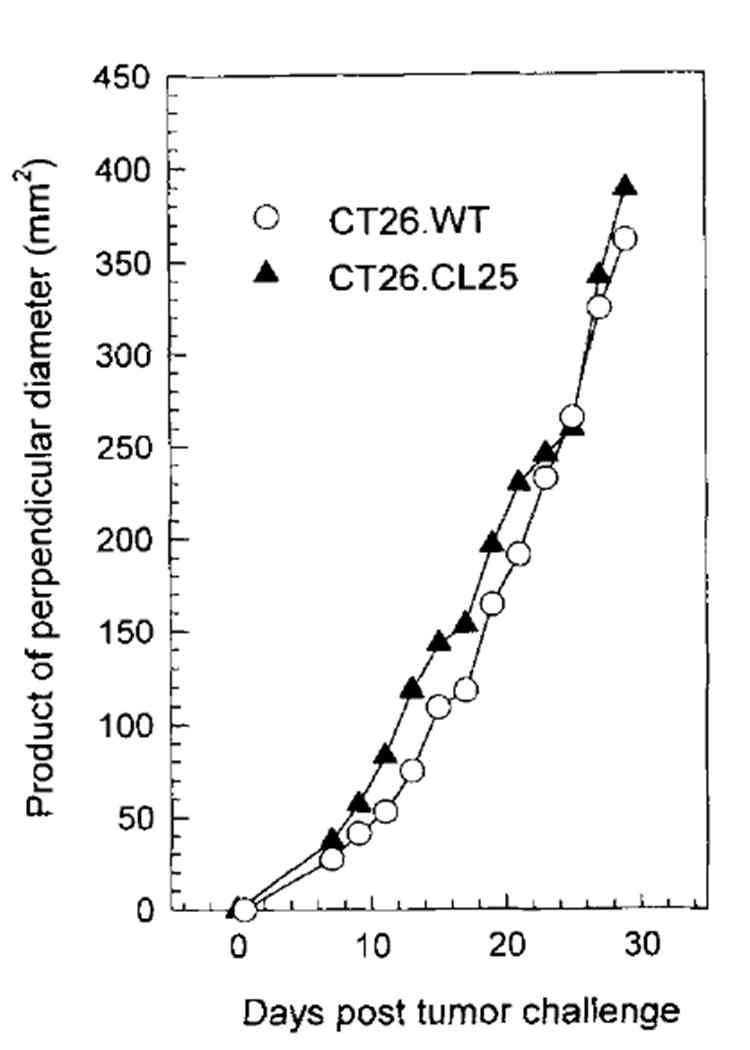

Retroviral transduction of CT-26 with lacZ does not change its growth rate or lethality

To establish a murine tumor model with a defined Ag, the undifferentiated colon carcinoma, CT26, of BALB/c (H-2d) origin, was cloned to generate the CT26.WT cell line, and was then retrovirally transduced with the gene for lacZ and subcloned to generate CT26.CL25. Although β-gal was expressed by CT26.CL25, it was as lethal as the parental clone, CT26.WT, in normal mice. As few as 103 s.c. injected tumor cells resulted in lethal tumors in 80% of mice, whereas 104 cells killed 100% of animals. Pulmonary metastases could be consistently established with both CT26.WT and CT26.CL25 tumors when unirradiated mice were injected i.v. with 104 cells. Like CT26.WT, CT26.CL25 grew aggressively and killed the majority of mice in 15 days at an i.v. dose of 5 × 105 cells. Doses of 105 cells injected i.v. resulted in death by day 19 in the absence of treatment (data not shown). As shown in Figure 1, the growth rates of transfected and nontransfected cells were identical. The virtually identical behavior of CT26.CL25 and CT26.WT was not caused by the loss of the transgene for β-gal or by the down-regulation of its expression in vivo, because histologic frozen sections of s.c. tumor showed positive, albeit attentuated X-gal staining in 100% of the tumor cells on day 30 after injection (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Unirradiated BALB/c mice (five per group) were injected with 3 × l05 tumor cells, both CT26.WT and CT26.CL25, in the right flank, and the product of the largest perpendicular diameters was calculated from measurements beginning on day 7 and every other day thereafter for a total of 12 measurements. The measurements were made in a coded, blinded fashion, and the values represent the average of five mice. The average deviation of the measurements has SD less than 10%. The experiment was repeated with similar results.

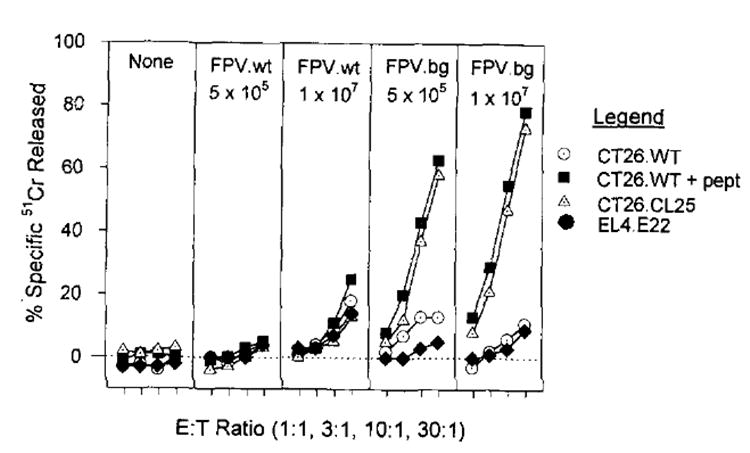

rFPV elicits specific, lytic TCD8+ after a single immunization

To test whether a TCD8+ response could be elicited against β-gal expressed by rFPV, a construct was made in which lacZ was driven by the 40-kDa promoter from vaccinia virus and designated FPV.bg40k. After immunization of BALB/c mice with 5 × 105 or 1 × 107 PFU of FPV.bg40k, splenocytes harvested on day 6, which in other model systems is the height of primary immune responses to vaccinia-encoded Ags (34), showed no measurable lysis of syngeneic tumor cells transfected with the model Ag or pulsed with the minimal determinant of β-gal (data not shown). However, when spleens from identically immunized mice were harvested on day 21 and cultured in vitro with 1 μg/ml of the nonamer TPHPARIGL for 7 days, they lysed CT26.WT pulsed with peptide as well as CT26.CL25 (Fig. 2). This lysis was specific; un-pulsed CT26.WT was not significantly lysed, nor was EL4 (H-2b) transfected with lacZ (clone E22), showing the MHC restriction of the response. Naïve splenocytes from unimmunized mice incubated under identical conditions failed to show any anti-β-gal activity, indicating that the lysis observed in the secondary cultures was not merely an in vitro phenomenon. Furthermore, splenocytes from mice immunized with the wild-type FPV were not primed, indicating specificity in the in vivo stage of stimulation.

Fig. 2. BALB/c mice were injected with either 5 × 105 or 1 × l07 PFU of FPV.wt or rFPV.bg40k.

Twenty-one days later, splenocytes from all the immunized mice and unimmunized mice (None) were restimulated with 1 μg/ml of synthetic peptide TPHPARIGL, for 7 days and then assayed for specific lysis in a 51Cr release assay against CT26.WT, CT26.WT pulsed with TPHPARICL, CT26.CL25, or EL4.E22 (an H-2b tumor that expresses β-gal). Spontaneous release for all reported 51Cr release assays is less than 10%. The experiment was repeated with similar results.

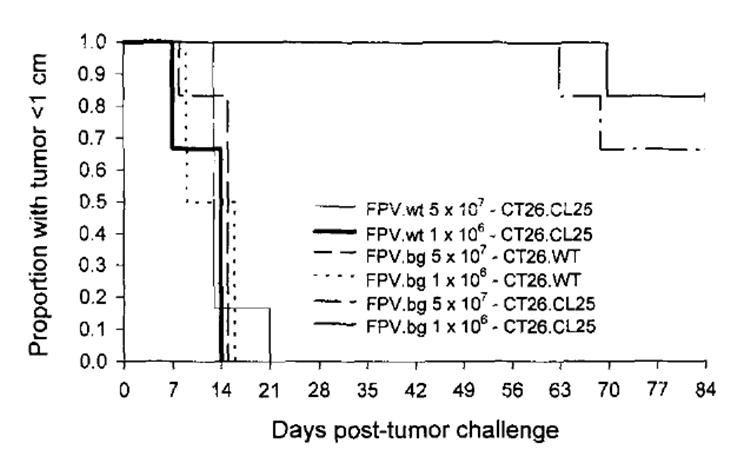

rFPV protects mice from s.c. and i.v. tumor challenge

Mice were injected with 106 or 5 × 107 PFU of rFPV.bg40k or control FPV.wt. Three weeks after immunization, mice were challenged with either 104 CT26.WT or CT26.CL25 administered s.c. on the right rear flank in 50 μl of HBSS. All mice were examined twice a week, and tumors were measured. Mice receiving FPV.bg40k showed protection from s.c. tumor challenge with CT26.CL25 at either dose (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 3). All mice receiving the parental tumor or immunization with FPV.wt developed tumors and were killed when tumor growth exceeded 1 cm in a single diameter.

Fig. 3.

Day 0, BALB/c mice immunized with 5 × 105 or 1 × l07 PFU of rFPV.40k or FPV.C. Day 21, the same mice were either challenged with CT26.W or CT26.CL25. Mice that developed tumors larger than 10 mrn in a single diameter were considered to have developed lethal tumors. All surviving mice have no palpable tumors. The figure represents two experiments each with six mice per group. The experiment was repeated with similar results.

When mice were challenged with 5 × 105 CT26.CL25 i.v., only the mice immunized with either dose of FPV.bg were protected (p < 0.0001) (Table I). On examination of the lungs on day 12 after tumor challenge, all lungs of immunized animals were completely devoid of any detectable tumor. Mice immunized with the control FPV.wt virus and challenged with either tumor did not show any protection at either dose. Additionally, mice immunized with FPV.bg40k but then challenged with the non-antigen-bearing tumor CT26.WT also went unprotected. These specificity controls demonstrated that Ag expression was necessary both in the immunizing virus and in the target tumor cell.

Table 1.

FPV prevents the establishment of pulmonary metastasisa

| (Avg No. Pulmonary Metastasis)b | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccine | Dosage | CT26.WT | CT26.CL25 |

| FPV.wt | 5 × 107 PFU | >500 | >500 |

| 1 × 106 PFU | >500 | >500 | |

| FPV.bg40k | 5 × 107 PFU | 438 | 0 |

| 1 × 106 PFU | >500 | 0 | |

a BALB/c mice were immunized with either 106 or 5 × 107 PFU of either FVP.bg40k or FPV.wt. Twenty-one days later, these mice were challenged i.v. with 5 × 105 CT2 6.WT or CT26.CL25. On day 12 after tumor challenge, lungs were harvested, and the number of pulmonary metastases were enumerated.

b >500 indicates that all mice in a group have more than 500 metastatic nodules. If any mice in the group have fewer than 500, the numbers are averaged together using the value of 500 in mice that have more than 500.

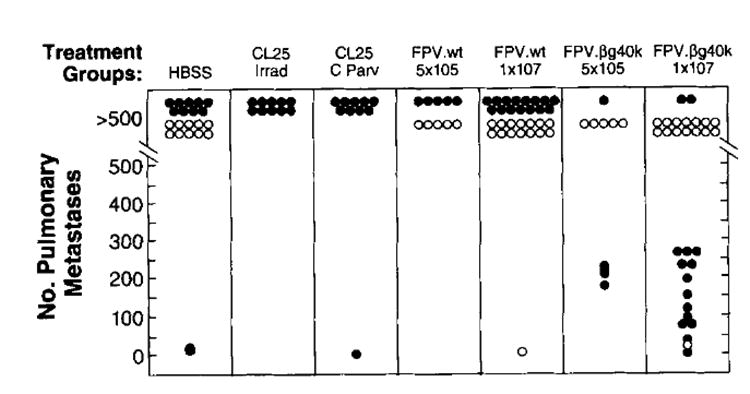

Active, specific immunotherapy with rFPV of established pulmonary metastases

To assess the ability of FPV.bg40k to generate specific therapeutic immune responses in tumor-bearing animals and to compare its efficacy against other methods of immunization, mice were injected i.v. with 5 × 105 CT26.WT or CT26.CL25 tumor cells and 3 days later immunized with either 5 × 105 or 1 × 107 PFU of FPV.bg40k, 5 × 105 or 107 PFU FPV.wt, or HBSS (all i.v.), or 5 × 105 irradiated CT26.CL25 or 5 × 105 CT26.CL25 admixed with 50 μg of Candida parvum in a total vol of 50 μl of HBSS s.c. (Fig. 4). There were no differences in pulmonary metastases at day 12 in mice injected with HBSS, or either dose of FPV.wt, or with either of the cellular vaccines. In contrast, treatment groups challenged with 5 × 105 CT26.CL25 i.v. and a single dose (107 PFU) of rFPV.bg showed a significant decrease (p < 0.0001) in the number of metastatic lung nodules on day 12. The lower-dose treatment group (5 × 105 PFU), although showing a response to treatment, had a larger tumor burden than mice treated at the higher dose of FPV.bg40k. There was no nonspecific response against the parental tumor in any treatment group, and FPV.wt had no treatment effect against CT26.CL25.

Fig. 4. BALB/c mice were injected i.v. with either 5 × 105 CT26.WT or CT26.CL25.

On day 3 after tumor challenge, mice were immunized i.v. with either 5 × 105 or 1 × 107 PFU of FPV.wt or rFPV.bg40k, or s.c. with either 5 × 105 irradiated (10,000 rad) CT26.CL25 or 5 × 105 CT26.CL25 admixed with 50 μg of C. parvum, or 0.5 ml of HBSS. On day 12 after tumor challenge, lungs were harvested, and the number of pulmonary metastases were enumerated in a coded, blinded fashion. Each data point represents an individual animal. Open circles represent animals bearing CT26.WT tumors, whereas closed circles represent animals bearing CT26.CL25. The experiment was repeated with similar results.

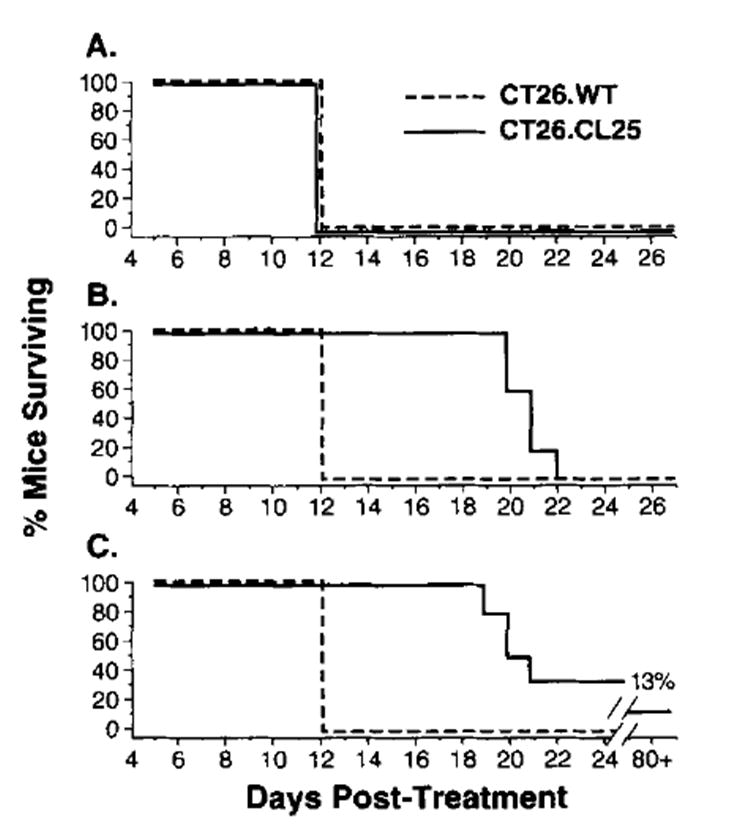

Active immunotherapy with FPV.bg40k also resulted in a significant survival advantage in mice bearing 3-day pulmonary metastasis from the injection of 5 × 105 CT26.CL25 (Fig. 5). Mice receiving no treatment, 107 PFU of FPV.wt, or challenge with the parental tumor all died by day 12 after treatment (day 15 after i.v. injection of tumor). Mice bearing CT26.CL25 receiving a single i.v. injection of 107 PFU of FPV.bg40k showed prolonged survival, but all mice died by day 22 (Fig. 5B). Of importance therapeutically, mice immunized twice with lo7 PFU of FPV.bg40k achieved prolonged survival, and 2 of 12 mice (one from each of two experiments), were cured of their disease (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5. BALB/c mice were challenged i.v. with 5 × 105 CT26.WT or CT26.CL25.

Mice were treated with HBSS (A), with one immunization with 1 × 107 PFU of FPV.bg40k on day 3 (B), or with two immunizations with 1 × 107 PFU of rFPV.bg40k on days 3 and day 10 (C). All mice treated with either one or twod oses of FPV.wt were found dead by day 12 after treatment (not shown). Mice were checked every day after day 12 for survival. The experiment was repeated with similar results.

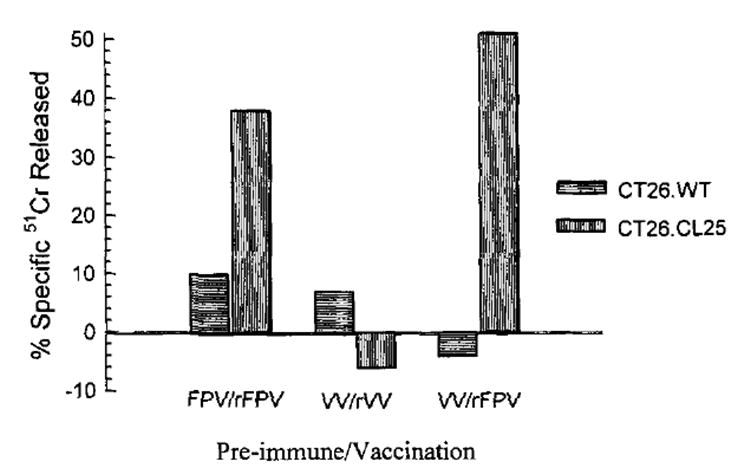

Preimmunization with rVV completely inhibits the response against a heterologous protein expressed by an rVV but not by an rFPV

Previous immunity to vaccinia may limit the effectiveness of rVV virus as an anticancer vaccine. To test whether previous immunity to vaccinia also diminishes the ability of rFPV to elicit a TCD8+ response, BALB/c mice were immunized with either wild-type VV or a control wild-type FPV. Two weeks later, mice prevaccinated with VV or FPV received subsequent vaccinations with either rVV expressing β-gal (HPV16-E6Vac) or FPV.bg40k. Fourteen days after the second injection, the spleens of all mice were harvested and placed in secondary culture, then evaluated on day 7 for specific β-gal target lysis in a 51Cr release assay. As shown in Figure 6, mice prevaccinated with VV completely inhibited the response against β-gal when challenged with HPV16-E6Vac. However, preimmunization with VV did not diminish a response elicited by FPV.bg40k. Interestingly, mice initially challenged with FPV did not suppress the anti-β-gal response when subsequently challenged with either HPV16-E6Vac or FPV.bg40k.

Fig. 6.

BALB/c mice were immunized with 1 × 107 FPV.wt or 5 × 106 VV.wt and 14 days after the first immunization, a second immunization with either 1 × 107 PFU of FPV.bg40k or 5 × 106 PFU of HPV-E6Vac (β-gal-expressing VV). On day 28, splenocytes from all micew ere restimulated in culture with 1 μM synthetic peptide TPHPARIGL for 7 days and then assayed for specific lysis in a 51Cr release assay against CT26.WT or CT26.CL25. Results for an effector-to-target ratio of 25:1 are shown. The experiment was repeated with similar results.

Discussion

The studies described in this communication used a murine tumor clone (CT26.CL25) that stably expressed β-gal as well as its class 1 MHC restriction element H-2 Ld. The growth characteristics and time to lethality of the transductant were not significantly different than the parental tumor clone CT26.WT in normal syngeneic, immuno competent mice. These results are similar to those obtained when the NP gene from vesicular stomatitis virus was transfected into the EL4 thymoma (35). Transfectants of a murine adenocarcinoma with human carcinoembryonic Ag retained their lethality but had a slight decrement in their growth rate (36). Thus, expression of a foreign Ag, whether it be of bacterial (β-gal), viral (NP), or xenogeneic (carcinoembryonic Ag) origin does not necessarily lead to the rejection of the experimental tumor.

Attempts to enhance the immunogenicity of tumor cells expressing β-gal by immunization of mice with irradiated CT26.CL25 did not efficiently activate an immune response. Immune activation was also not seen with the use of the nonspecific immunostimulant C. parvum (Fig. 4). Furthermore, lymphocytes obtained from tumor-bearing mice showed no measurable responsiveness in cytotoxicity assays even after secondary stimulation with the Ld-restricted β-gal peptide, TPHPARIGL (data not shown). The lack of immunogenicity of CT26.CL25 could not be explained by down-regulation of MHC class I molecules or by loss of the experimental Ag. Thus, although β-gal is a large protein (1023 amino acids with an Mr of 116,353 Da) (37, 38), originates from E. coli, and has very little homology to any known mammalian protein, it fails to elicit a measurable immune response as a model tumor Ag.

Qualitative changes in the immune response were observed when mice were immunized with the rFPV expressing lacZ, FPV.bg40k: The virus elicited powerful, specific cytotoxic responses and rejected a tumor cell challenge. Most impressively, immunization of mice bearing 3-day-old pulmonary metastasis significantly diminished the number and size of the tumor burden and significantly prolonged the survival of these mice. The critical immunologic differences between the expression of an Ag by a recombinant poxvirus and its expression by a tumor cell are not well understood, but issues of immune activation vis-à-vis immunologic help, immune suppression, and costimulation are likely to play important roles. Whatever the mechanisms, the potential implication of this finding for the development of anticancer vaccines is that immunization with a recombinant virus expressing a TAA may significantly enhance the immunostimulatory properties of the TAA.

Recombinant poxviruses, of which the prototype is VV, are excellent candidates for the expression of a TAA (8, 9). VV has a proven safety record, because it was administered to approximately 1 billion human beings in the world-wide eradication of smallpox. However, the use of rVV as a specific immunostimulant is limited, because virtually everyone born before 1971 was vaccinated with VV in childhood. Previous reports have shown that mice that received previous immunizations with VV did not mount a strong immune response against heterologous proteins expressed by rVV in a subsequent challenge (39), and similar findings were seen in humans (40, 41). Presumably, previous immunization resulted in a potent secondary or anamnestic response against VV-encoded proteins, where as only a weak primary response was mounted against the heterologous protein. Previous immunization with VV was found to inhibit both primary (Restifo NP, unpublished observations) and secondary responses to heterologous protein expressed by rVV (as shown in Fig. 6). Another significant problem associated with rVV-based vaccines is that they are replication competent in man and could pose the problem of disseminated viremia in severely immunocompromised individuals, such as patients with AIDS (40, 42, 43). The use of FPVs can circumvent both of these problems. Previous immunization of mice with VV did not inhibit a cytotoxic T cell response against heterologous protein expressed by rFPV, and FPV is replication incompetent in mammals (11), thus adding a substantial measure of safety.

The human melanoma tumor Ags cloned thus far are normal, nonmutated self proteins (1, 4, 5). Antimelanoma T cells recognize normal melanocytes (44), as do virtually all antitumor CD8+ T cell cultures grown in our laboratory (6, 7). Although some patients treated with these T cell cultures develop vitiligo, serious autoimmune disease has not been observed. The murine tumor model system described here lends itself to the study of tolerance because of the numerous types of mice transgenic for β-gal (45). In fact, transgenic mice expressing β-gal in spleen and bone marrow were found to be partially tolerant to the β-gal protein in studies of Ab generation (17). Studies are ongoing in our laboratory to determine the nature of the differences in the cellular immune responses against β-gal in transgenic and nontransgenic animals, as well as the influence of viral structure, dosing, and kinetics on the breaking of tolerance. Finally, the question of whether autoimmune disease will be induced if tolerance is broken must be addressed. To this end, we are currently studying immune reactivities against the murine homologs of MART-1 and gp100, as well as the using the P815A Ag (46, 47).

rFPVs are now being constructed that express two human melanoma Ags, gpl00 and MART-1 (6, 7), for use in clinical trials. One therapeutic strategy under consideration involves immunization with a recombinant virus to enhance the precursor frequency of autologous T cells reactive with gpl00 or MART-1 (or both) as a prelude to ex vivo expansion and adoptive transfer of reactive T cells. This strategy is based on observations that adoptive immunotherapy using Ag-specific lymphocytes can mediate cancer regression in selected patients with metastatic melanoma (48, 49). We now have constructed and are testing the second generation of recombinant poxviruses that co-express model tumor Ags together with cytokines (IL-2, IL-12, granulocyte-macrophage CSF, etc) and costimulatory molecules (B7-1, B7-2, ICAM-1, etc.) alone and in a variety of combinations. These experimental approaches are based on a growing understanding of the mechanisms of immune activation and ultimately may lead to successful immunotherapies of human cancer and infectious diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank P. Hwu, B. Cowherd, and J. Treisman for help with the creation of the CT26.CL25 cell line, Y. Paterson, M. Bevan, and B. Moss for critical reagents, D. Jones and P. Spiess for help with the animal experiments, and J. Bennink, M. Gavin, and J. Yewdell for helpful discussions.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- TAA

tumor-associated Ags

- TCD8+

CD8+ T cells

- rFPV

recombinant fowlpox virus

- β-gal

β-galactosidase

- G418

Geniticin

- rVV

recombinant vaccinia virus

- NP

nucleoprotein

- PFU

plaque-forming unit

References

- 1.Boon T, Cerottini J, Van den Eynde B, van der Bruggen P, Van Pel A. Tumor antigens recognized by T lymphocytes. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:337. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.002005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brichard V, Van Pel A, Wolfel T, Wolfel C, De Plaen E, Lethe B, Coulie P, Boon T. The tyrosinase gene codes for an antigen recognized by autologous cytolytic T lymphocytes on HLA-A2 melanomas. J Exp Med. 1993;178:489. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.2.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cox AL, Skipper J, Chen Y, Henderson RA, Darrow TL, Shabanowitz J, Engelhard VH, Hunt DF, Slingluff CL., Jr Identification of a peptide recognized by five melanoma-specific human cytotoxic T cell lines. Science. 1994;264:716. doi: 10.1126/science.7513441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Houghton AN. Cancer antigens: immune recognition of self and altered self. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pardoll DM. Tumour antigens. A new look for the 1990s. Nuture. 1994;369:357. doi: 10.1038/369357a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawakami Y, Eliyahu S, Delgado CH, Robbins PF, Rivoltini L, Topalian SL, Miki T, Rosenberg SA. Cloning of the gene coding for a shared human melanoma antigen recognized by autologous T cells infiltrating into tumor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawakami Y, Eliyahu S, Delgado CH, Robbins PF, Sakaguchi K, Appella E, Yannelli JR, Adema GJ, Miki T, Rosenberg SA. Identification of a human melanoma antigen recognized by tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes associated with in vivo tumor rejection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moss B. Poxvirus vectors: cytoplasmic expression of transferred genes. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1993;3:86. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(05)80346-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moss B. Vaccinia virus: a tool for research and vaccine development. Science. 1991;252:1662. doi: 10.1126/science.2047875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baxby D, Paoletti E. Potential use of non-replicating vectors as recombinant vaccines. Vaccine. 1992;10:8. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(92)90411-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Somogyi P, Frazier J, Skinner MA. Fowlpox virus host range restriction: gene expression, DNA replication, and morphogenesis in nonpermissive mammalian cells. Virology. 1993;197:439. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boyle DB, Heine HG. Recombinant fowlpox virus vaccines for poultry. Immunol Cell Biol. 1993;71:391. doi: 10.1038/icb.1993.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qingzhong Y, Barrett T, Brown TD, Cook JK, Green P, Skinner MA, Cavanagh D. Protection against turkey rhinotracheitis pneumovirus (TRTV) induced by a fowlpox virus recombinant expressing the TRTV fusion glycoprotein (F) Vaccine. 1994;12:569. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(94)90319-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor J, Weinberg R, Languet B, Desmettre P, Paoletti E. Recombinant fowlpox virus inducing protective immunity in non-avian species. Vaccine. 1988;6:497. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(88)90100-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wild F, Giraudon P, Spehner D, Drillien R, Lecocq JP. Fowlpox virus recombinant encoding the measles virus fusion protein: protection of mice against fatal measles encephalitis. Vaccine. 1990;8:441. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(90)90243-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rammensee HG, Schild H, Theopold U. Protein-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Recognition of transfectants expressing intracellular, membrane-associated or secreted forms of β-galactosidase. Immunogenetics. 1989;30:296. doi: 10.1007/BF02421334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Theopold U, Kohler G. Partial tolerance in beta-galactosidase-transgenic mice. Eur J Irnmunol. 1990;20:1311. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830200617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schafer R, Portnoy DA, Brassell SA, Paterson Y. Induction of a cellular immune response to a foreign antigen by a recombinant Listeria monocytopnes vaccine. J Immunol. 1992;149:53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampson LA, Lampson MA, Dunne AD. Exploiting the lacZ reporter gene for quantitative analysis of disseminated tumor growth within the brain: use of the lacZ gene product as a tumor antigen, for evaluation of antigenic modulation, and to facilitate image analysis of tumor growth in situ. Cancer Res. 1993;53:176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dick LR, Aldrich C, Jameson SC, Moomaw CR, Pramanik BC, Doyle CK, DeMartino GN, Bevan MJ, Forman JM, Slaughter CA. Proteolytic processing of ovalbumin and beta-galactosidase by the proteasome to a yield antigenic peptides. J Immunol. 1994;152:3884. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gavin MA, Gilbert MJ, Riddell SR, Greenberg PD, Bevan MJ. Alkali hydrolysis of recombinant proteins allows for the rapid identification of class I MHC-restricted CTL epitopes. J Immunol. 1993;151:3971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brattain MG, Strobel-Stevens J, Fine D, Webb M, Sarrif AM. Establishment of mouse colonic carcinoma cell lines with different metastatic properties. Cancer Res. 1980;40:2142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller AD, Rosman GJ. Improved retroviral vectors for gene transfer and expression. Biotechniques. 1989;7:980. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller AD, Buttimore C. Redesign of retrovirus packaging cell lines to avoid recombination leading to helper virus production. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:2895. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.8.2895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Markowitz D, Goff S, Bank A. A safe packaging line for gene transfer: separating viral genes on two different plasmids. J Virol. 1988;62:1120. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.4.1120-1124.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jenkins S, Gritz L, Fedor CH, O’Neill EM, Cohen LK, Panicali DL. Formation of lentivirus particles by mammalian cells infected with recombinant fowlpox virus. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1991;7:991. doi: 10.1089/aid.1991.7.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosel JL, Earl PL, Weir JP, Moss B. Conserved TAAATG sequence at the transcriptional and translational initiation sites of vaccinia virus late genes deduced by structural and functional analysis of the HindIII H genome fragment. J Virol. 1986;60:436. doi: 10.1128/jvi.60.2.436-449.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith GL, Levin JZ, Palese P, Moss B. Synthesis and cellular location of the ten influenza polypeptides individually expressed by recombinant vaccinia viruses. Virology. 1987;160:336. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(87)90004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eisenlohr LC, Bacik I, Bennink JR, Bernstein K, Yewdell JW. Expression of a membrane protease enhances presentation of endogenous antigens to MHC class I-restricted T lymphocytes. Cell. 1992;71:963. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90392-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Restifo NP, Esquivel F, Kawakami Y, Yewdell JW, Mule JJ, Rosenberg SA, Bennink JR. Identification of human cancers deficient in antigen processing. J Enp Med. 1993;177:265. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.2.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Restifo NP, Esquivel F, Asher AL, Stötter H, Barth RJ, Bennink JR, Mulé JJ, Yewdell JW, Rosenberg SA. Defective presentation of endogenous antigens by a murine sarcoma: implications for the failure of an anti-tumor immune response. J Immunol. 1991;147:1453. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mule JJ, Yang JC, Lafreniere R, Shu S, Rosenberg SA. Identification of cellular mechanisms operational in vivo during the regression of established pulmonary metastases by the systemic administration of high-dose recombinant interleukin-2. J Immunol. 1987;139:285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Restifo NP, Spiess PJ, Karp SE, Mule JJ, Rosenberg SA. A nonimmunogenic sarcoma transduced with the cDNA for interferon gamma elicits CD8+ T cells against the wild-type tumor: correlation with antigen presentation capability. J Exp Med. 1992;175:1423. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.6.1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Restifo NP, et al. J Immunol. In Press. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kundig TM, Bachmann MF, Lefrancois L, Puddington L, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel RM. Nonimmunogenic tumor cells may efficiently restimulate tumor antigen-specific cytotoxic T cells. J Immunol. 1993;150:4450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kantor J, Irvine K, Abrams S, Kaufman H, DiPietro J, Schlom J. Antitumor activity and immune responses induced by a recombinant carcinoembryonic antigen-vaccinia virus vaccine. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1992;84:1084. doi: 10.1093/jnci/84.14.1084. see comments. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kalnins A, Otto K, Ruther U, Muller-Hill B. Sequence of the lacZ gene of Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 1983;2:593. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1983.tb01468.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fowler AV, Zabin I. Amino acid sequence Of beta-galactosidase. XI. Peptide ordering procedures and the complete sequence. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:5521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Battegay M, Moskophidis D, Waldner H, Brundler MA, Fung-hung WP, Mak TW, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel RM. Impairment and delay of neutralizing antiviral antibody responses by virus-specific cytotoxic T cells. J Immunol. 1993;151:5408. published erratum appears in J. Immunol. 1994;152:1635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McElrath MJ, Corey L, Berger D, Hoffman MC, Klucking S, Dragavon J, Peterson E, Greenberg PD. Immune responses elicited by recombinant vaccinia-human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) envelope and HIV envelope protein: analysis of the durability of responses and effect of repeated boosting. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:41. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cooney EL, Collier AC, Greenberg PD, Coombs RW, Zarling J, Arditti DE, Hoffman MC, Hu SL, Corey L. Safety of and immunological response to a recombinant vaccinia virus vaccine expressing HIV envelope glycoproteins. Lancet. 1991;337:567. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91636-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Graham BS, Matthews TJ, Belshe RB, Clements ML, Dolin R, Wright PF, Gorse GJ, Schwartz DH, Keefer MC, Bolognesi DP. Augmentation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 neutralizing antibody by priming with gp160 recombinant vaccinia and boosting with rgpl60 in vaccinia-naive adults. The NIAID AIDS Vaccine Clinical Trials Network. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:533. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.3.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnson RP, Hammond SA, Trocha A, Siliciano RF, Walker BD. Induction of a major histocompatibility complex class I-restricted cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response to a highly conserved region of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) gp120 in seronegative humans immunized with a candidate HIV-1 vaccine. J Virol. 1994;68:3145. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.3145-3153.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anichini A, Maccalli C, Mortarini R, Salvi S, Mazzocchi A, Squarcina P, Herlyn M, Parmiani G. Melanoma cells and normal melanocytes share antigens recognized by HLA-A2-restricted cytotoxic T cell clones from melanoma patients. J Exp Med. 1993;177:989. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.4.989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cui C, Wani MA, Wight D, Kopchick J, Stambrook PJ. Reporter genes in transgenic mice. Transgenic Res. 1994;3:182. doi: 10.1007/BF01973986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lethe B, Van den Eynde B, Van Pel A, Corradin G, Boon T. Mouse tumor rejection antigens P815A and P815B: two epitopes carried by a single peptide. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:2283. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van den Eynde B, Lethe B, Van Pel A, De Plaen E, Boon T. The gene coding for a major tumor rejection antigen of tumor P81S is identical to the normal gene of syngeneic DBA/2 mice. J Exp Med. 1991;173:1373. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.6.1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Greenberg PD. Adoptive T cell therapy of tumors: mechanisms operative in the recognition and elimination of tumor cells. Adv Immunol. 1991;49:281. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60778-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rosenberg SA, Yannelli JR, Yang JC, Topalian SL, Schwartzentruber DJ, Weber IS, Parkinson DR, Seipp CA, Einhorn JH, White DE. Treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma with autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and interleukin 2. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:1159. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.15.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]