Abstract

Objective

Myocardial gene therapy continues to show promise as a tool for investigation and treatment of cardiac disease. Progress toward clinical approval has been slowed by limited in vivo delivery methods. We investigated the problem in a porcine model, with an objective of developing a method for high efficiency, homogeneous myocardial gene transfer that could be used in large mammals, and ultimately in humans.

Methods

Eighty-one piglets underwent coronary catheterization for delivery of viral vectors into the left anterior descending artery and/or the great cardiac vein. The animals were followed for 5 or 28 days, and then transgene efficiency was quantified from histological samples.

Results

The baseline protocol included treatment with VEGF, nitroglycerin, and adenosine followed by adenovirus infusion into the LAD. Gene transfer efficiency varied with choice of viral vector, with use of VEGF, adenosine, or nitroglycerin, and with calcium concentration. The best results were obtained by manipulation of physical parameters. Simultaneous infusion of adenovirus through both left anterior descending artery and great cardiac vein resulted in gene transfer to 78 ± 6% of myocytes in a larger target area. This method was well tolerated by the animals.

Conclusions

We demonstrate targeted, homogeneous, high efficiency gene transfer using a method that should be transferable for eventual human usage.

Keywords: Gene therapy, Myocytes, Capillary permeability, Regional blood flow

1. Introduction

Gene therapeutics have tremendous potential to revolutionize treatment of cardiac diseases, but clinical successes have come more slowly than originally predicted. Problems limiting gene transfer efficacy include inadequate delivery to the target tissue, loss of therapeutic effect, and negative interactions with the host immune system. Of these, the delivery issue is fundamental, since all else is irrelevant if the gene never reaches the target. Previously reported myocardial delivery methods include intramyocardial injection [1], coronary catheterization [2,3], pericardial delivery [4,5], ventricular cavity infusion during aortic cross-clamping [6,7], and perfusion during cardiopulmonary bypass [8,9]. Each of these methods is limited by either efficacy or tolerability. The best method reported so far is a cross-clamp protocol where hamsters were cooled to 18°C during a 5 minute infusion of histamine and adenovirus, resulting in gene transfer to 77% of cardiac myocytes [10]. These rigorous conditions illustrate the difficulty in obtaining reasonable levels of myocardial gene transfer. The success of the hamster model provides an opportunity to investigate gene transfer effects in rodents and small mammals, but the ability to translate this delivery method for use in large mammals or humans has never been demonstrated.

We previously reported the role of several parameters relevant to gene transfer efficiency in rabbit ex vivo and in vitro models [11–13]. The goal of the current report was to build an effective myocardial gene transfer method by sequentially exploring these variables in the large mammal in vivo environment. We also monitored general parameters of animal tolerance with the overall goal of defining conditions that could eventually be used in humans.

2. Methods

2.1. Viral vectors

Adβgal was a serotype 5 adenovirus deleted of the E1 and E3 genes, containing the Escherichia coli lac Z gene driven by the cytomegalovirus immediate early promoter. Adenoviruses were expanded in HEK-293 cells and purified by passage through Adenopur columns (Puresyn, King of Prussia, PA). The concentrated virus supplemented with 10% glycerol was dialyzed overnight against PBS with 1mM MgCl2, and stored at –80° C until use. Virus particle concentration is calculated from the absorbance at 260 nm and the ratio of absorbance at 260 and 280 nm (A260/A280). The infectious titer is determined by plaque assay. Transgene expression is confirmed by infection of a Cos−7 cells, a non-permissive cell line. The absence of replication competent virus is confirmed by pseudo-plaque assay on Cos−7 cells, documenting the absence of cytolytic activity.

Adeno-associated virus (AAV)2-βgal and AAV6-βgal were serotype 2 and pseudotype 6, respectively. Both contained the Escherichia coli lac Z gene driven by the cytomegalovirus immediate early promoter. AAV2-βgal was made by triple transfection as previously reported [14]. AAV6-βgal was amplified using the same process, except the AAV-6 capsid gene was used rather than the AAV-2 capsid gene [15]. Both AAV were purified by sequential passage through an iodixanol step gradient and a sepharose Q ion exchange column. AAV stocks were stored at −80° C until use. The adeno-associated viruses were donated by Genzyme Corp. (Boston, MA).

2.2. Gene transfer procedure

Eighty-one 1–2 month old pigs weighing 5–7 kg were included in this study. The pigs received sildenafil 25mg orally, 30 minutes before cardiac catheterization. General anesthesia was induced with ketamine/xylazine/telazol, and the animals were intubated. Anesthesia was maintained with isoflurane. After surgical access to the neck vessels, guiding catheters were introduced through right carotid artery and/or jugular vein into the left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) and/or the coronary sinus, respectively. Through the guiding catheters, 2.7 Fr balloon catheters were inserted into the middle portion of LAD just distal to the second diagonal branch and/or the great cardiac vein (GCV) as noted in the individual protocols. The LAD and/or GCV balloons were expanded to 3 Atm for the duration of pretreatment and virus solution infusions as indicated in the individual delivery protocols. The baseline protocol delivered to the LAD alone, so coronary sinus and GCV catheters were not used. Baseline pretreatment consisted of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) 0.5 μg/ml, nitroglycerin (TNG) 250 μg/ml, adenosine 5 mg/ml and 1.0 mM calcium concentration in 10 ml of Krebs’s solution infused over 3 minutes. After pretreatment, 6 × 1010 pfu (3 × 1012 vp) Adβgal or 3 × 1012 vp AAVβgal were delivered in 12 ml of Krebs’s solution containing the same concentrations of adenosine, calcium and TNG as the pretreatment. VEGF was included in the pretreatment but not in the virus delivery solution. All solutions were passed through 0.2μm filters prior to use. Virus delivery occurred over 2 minutes at a coronary flow rate of 6 ml/min. During delivery, heart rate, blood pressure, end-tidal carbon dioxide and pulse oximetry were monitored. The baseline protocol was performed in 6 animals. All other protocols were tested in 3 animals with exception of the combined LAD and GCV delivery protocol, which was tested in 6 animals.

The investigation conforms with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85–23, revised 1996). The experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.3 Evaluation of transgene efficiency

Five days after the procedure, animals were sacrificed. The hearts were removed and rinsed with ice-cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS). For histological analysis, the heart was cut into three sections: right atrial and ventricular free wall, left atrial and ventricular free wall, and atrial and ventricular septa, and then the sections were sliced at approximate intervals of 3–5 mm. The tissues were fixed and stained with X–gal using conventional methods [11, 16]. X-gal staining was always performed at pH 8.0 to minimize non-specific staining [17].

Two measures were used to define the level of in vivo myocardial gene transfer. Measurement of the gross dimensions of the X-gal stained blue volume provided an idea of the overall quantity of tissue involved, and calculation of the percentage of blue cells on microscopic analysis gave an idea of the gene transfer efficiency within the grossly blue tissue. Digital photographs of the gross tissues were taken to quantify the gene transfer tissue volume. The volume of blue tissue was obtained by measurement of blue surface area and depth of penetration after X-gal staining. Digital pictures were taken of the X-gal stained gross tissue, and the blue area was identified and measured using Image J software (NIH). For the microscopic examination, sections of the grossly blue area were cut to 8 μm thickness. The percentage of cells expressing β-galactosidase was determined by averaging counts of cells from 5 microscopic sections randomly selected from within the grossly stained blue region (100 cells per section, 500 cells per animal).

2.4. Statistical analysis

All parameters are summarized as mean ± SEM. Since means in the multiple groups were compared, an ANOVA model was performed. Since the overall p-value was less than 0.05 and the data were not balanced, Tukey’s studentized range test was used to control for multiple comparisons. The corrected p-values were reported. A p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline

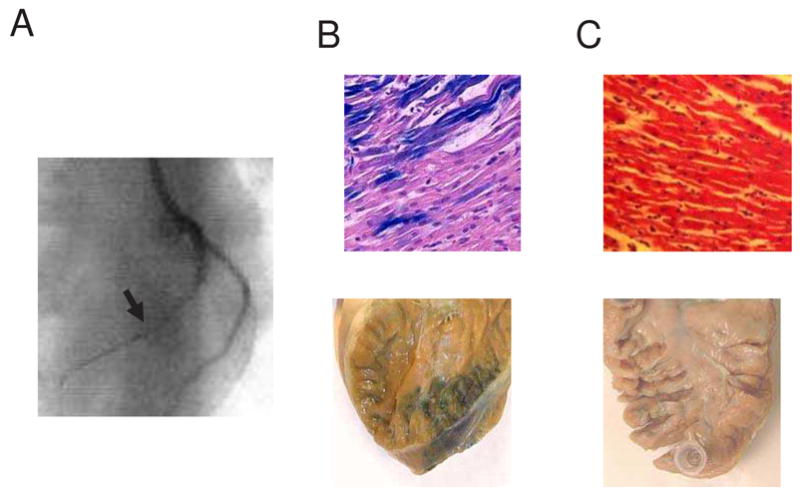

Our starting point was chosen to have a mid-range level of gene transfer, so that any increase or decrease in gene transfer efficiency could be easily distinguished from the baseline. To achieve this, we chose mid-range levels of several factors previously shown to play roles in either the ex vivo or the small mammal in vivo environment [11–13,18,19]. Intracoronary pretreatment and virus solutions were delivered to the mid-LAD, immediately after the second diagonal branch (Figure 1A). Pretreatment included oral sildenafil and intracoronary VEGF, TNG, and adenosine in 1 mM calcium Krebs’s solution. After pretreatment, 5 × 109 pfu/ml Adβgal was delivered in Krebs’s solution containing the same concentrations of adenosine, calcium and TNG as the pretreatment. These starting conditions led to successful gene transfer in a region that included the mid- to apical-anterior septum, and septal RV and LV anterior free wall. On gross staining, 7 ± 2% of the entire septal volume showed blue, X-gal staining. Within this blue region, microscopic examination revealed that 34 ± 3% of cells expressed the transgene. (Figure 1B). Control experiments using null constructs failed to show any blue coloration, demonstrating that the blue X-gal staining is specific for gene transfer, rather than non-specific or endogenous β-galactosidase activity in the target tissue (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

(A) Fluoroscopic image of catheter position during the gene transfer procedure into the LAD. The arrowhead indicates the balloon catheter position. (B) X-gal stained gross and microscopic sections of Adβgal exposed hearts after gene transfer using the baseline protocol (VEGF 0.5 μg/ml, TNG 250 μg/ml, adenosine 5 mg/ml and 1.0 mM calcium). (C) X-gal stained gross and microscopic sections after exposure to AdNull control using the baseline protocol. Microscopic sections are counterstained with hematoxylin-eosin and magnified 400X.

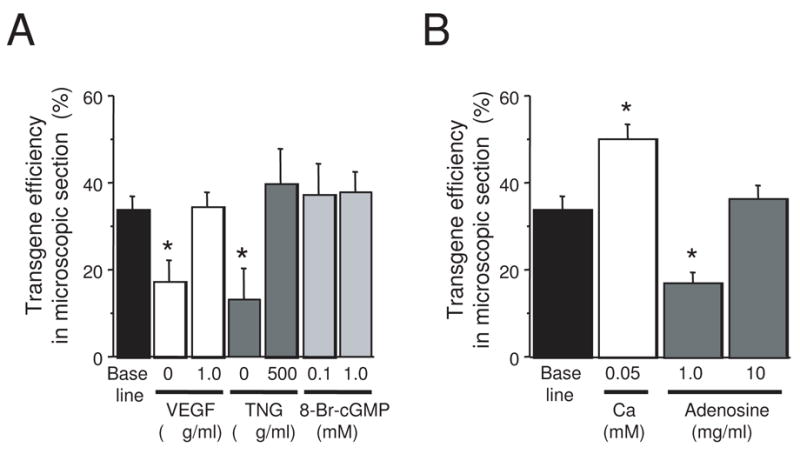

3.2. Nitric oxide/cyclic GMP-mediated vascular permeability

We evaluated the role of VEGF, the nitric oxide donor TNG, and the cGMP analogue 8-Br-cGMP by manipulating each factor individually, while keeping the remaining conditions constant (Figure 2A). Removal of VEGF reduced the gene transfer rate to 17 ± 5% (p=0.01), and increasing the concentration to 1μg/ml did not differ significantly from the baseline condition (32 ± 8%, p=NS). Likewise, removal of TNG reduced gene transfer (13 ± 7%, p<0.01), and increasing the dose to 500 μg/ml did not significantly enhance gene transfer (40 ± 8%, p=NS). We tested cyclic-GMP at 3 concentrations: baseline (0 mM), 0.1 and 1 mM. All tests were performed in the presence of all other baseline agents (sildenafil, nitroglycerin, VEGF, and adenosine). There were no significant differences between the 3 groups (34 ± 3%, 37 ± 7% and 38 ± 5%, respectively). Gross tissue evaluation revealed that none of the permeability manipulations had any significant effect on the size or distribution of the gene transfer region.

Figure 2.

(A) Effect of cGMP-dependent vascular permeability agents on gene transfer efficacy. (B) Effect of calcium and adenosine. In both graphs, the transgene efficiency was determined as the percentage of X-gal positive cells within the grossly blue area. (n = 6 for baseline, n = 3 for all other groups, * signifies p ≤ 0.01).

3.3. Calcium

Reducing calcium concentration increased transgene efficiency within the target area, but it did not affect the overall size of that area. When pretreatment and virus solutions contained all of the baseline vasodilation and permeability compounds in 0.05 mM calcium, 46 ±3% of cells expressed the transgene, which was significantly better than the above baseline 1 mM calcium concentration (p=0.02, Figure 2B). Prior experience had taught us that the calcium effect seemed to be ‘all-or-none’, so we did not test other concentrations.

3.4. Adenosine

Unlike VEGF, TNG, and low calcium, adenosine has strong vasodilatory effects, but it decreases microvascular permeability in porcine coronary arteries [20]. Reducing adenosine concentration to 1 mg/ml from the baseline (5 mg/ml) caused a significant reduction in gene transfer (17 ± 2 %, p=0.03, Figure 2B). Increasing adenosine to 10 mg/ml did not have a statistically significant effect compared to baseline (39 ± 1%, p = NS). There was no effect on the size of the gene transfer region with the adenosine manipulations, and there was no effect on atrioventricular conduction with any concentration of adenosine administered through the LAD.

3.5. Viral vector

We compared adeno-associated virus (AAV) serotypes 2 and 6 with the baseline vector (adenovirus serotype 5). Delivery was performed using the baseline parameters, except that the 0.05 mM calcium concentration was used. Since the AAV serotypes attach to different receptors than adenovirus, concentration was measured as virus particle numbers rather than plaque forming units for dosing comparability. The longer time course of expression for AAV required measurement of gene expression at 28 days, rather than the 5 day experiments for adenovirus. On gross tissue evaluation, AAV showed a similar distribution pattern as adenovirus. The gene transferred region encompassed the mid- to apical anterior septum and the septal RV and LV free walls. The size of the gene transfer region was not significantly different compared to adenovirus. Relative to the adenovirus (46 ± 3%), both AAV serotypes had decreased gene transfer efficiency, although AAV-6 outperformed AAV-2 (38 ± 2% vs. 27 ± 6%, p=0.02).

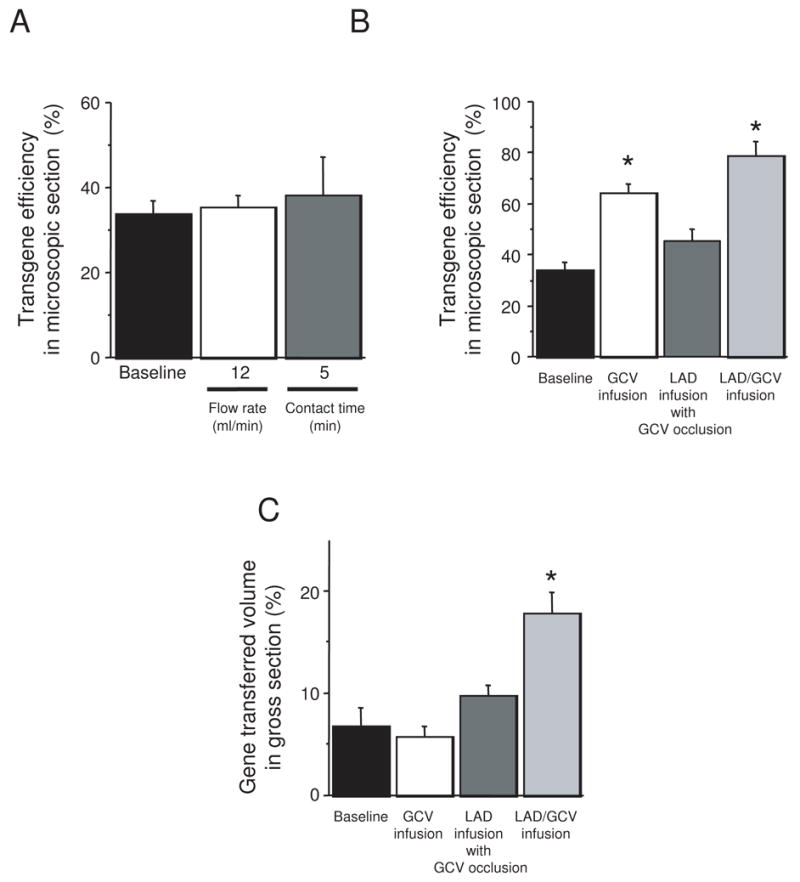

3.6. Coronary flow characteristics

Physical factors related to virus delivery were evaluated by manipulating coronary flow rate, virus contact time, and the effects of GCV involvement in delivery. Baseline coronary flow rate in these experiments was 6 ml/min, with balloon occlusion to prevent virus backflow into other coronaries or contamination of virus solutions with blood. Increasing coronary flow to 12 ml/min or increasing virus contact time to 5 minutes did not significantly affect the size or shape of the gene transfer area, or the percentage of transgene expressing cells within the area (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Effects of coronary flow characteristics. (A) Effect of coronary flow rate and virus contact time. (B) Effect of utilizing great cardiac vein in virus delivery. (C) Comparison of delivery method to the gross volume of myocardium expressing the transgene. (n = 6 for baseline and LAD/GCV groups, n = 3 for all other groups, * signifies p ≤ 0.01).

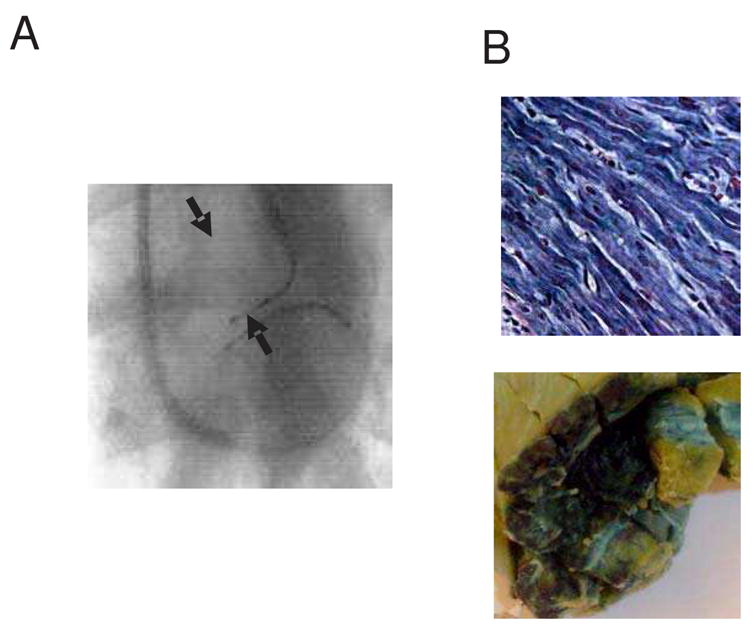

The percentage of cells expressing the transgene improved substantially when we included the cardiac venous system in the delivery circuit (Figure 3B), and for the first time, the size and shape of the gene transfer region changed as well (Figure 3C). Virus infusion through GCV alone improved gene transfer compared to LAD infusion (64 ± 4%, p<0.001). Notably, GCV infusion did not change the overall septal volume expressing the transgene, but it changed the distribution. Unlike the baseline LAD delivery method where gene expression tended toward the RV side of the septum (RV septal surface area 10 ± 3% of total RV septal surface, LV septal surface area 3 ± 1% of total LV septal surface), delivery through the GCV decreased transgene expression to 4 ± 0% of the RV septal surface area and increased it to 8 ± 2% of the LV septal surface area. Like the baseline situation, the gene transferred area was limited to the mid-septum and did not extended to apex. Delivery through LAD with occlusion of the GCV showed a trend toward increased transgene expression within the target region (45 ± 4%, p=0.13), with an accentuation of the LAD delivery pattern: 18 ± 2% of the RV septal surface area expressed the transgene and only 2 ± 1% of the LV septal surface was blue. Simultaneous infusion through LAD and GCV exhibited additive effects in overall transgene efficiency of 78 ± 6 % (p<0.001, Figure 4) and distribution of the transgene (21±3 % in right and 14±4% in left side). The overall volume of the gene expressing area for simultaneous LAD and GCV infusion was significantly higher than the baseline method (18 ± 2% of septal volume, p < 0.001).

Figure 4.

(A) Fluoroscopic image of catheter position during the gene transfer procedure with simultaneous infusion through both LAD and GCV. Arrowheads indicate the balloon catheter positions. (B) X-gal stained gross and microscopic sections of Adβgal exposed hearts after gene transfer using the LAD and GCV simultaneous perfusion protocol (Magnification 400X). Slides are stained with X-gal and counterstained with hematoxylin-eosin.

3.7. Safety

During the gene transfer procedure, we monitored blood pressure, heart rate and rhythm, pulse oximetry and end-tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO2). Infusion of the pretreatment and virus solutions caused an immediate systolic blood pressure decrease of 30 mmHg that stabilized within the first minute of perfusion. The average heart rate also decreased to 50–60/min and then stabilized over the same time course. There were no changes in pulse oximetry or ETCO2. After infusion, vital signs returned to baseline over 2–5 minutes without need for any intervention. High dose TNG (500 μg/ml) caused a 50–60 mm Hg drop in blood pressure; otherwise there were no differences between groups in hemodynamic tolerance of the pretreatment solutions.

Ventricular fibrillation (VF) occurred during coronary infusion in 5 of the first 10 pigs (50%), and 4 out of remaining 71 pigs (5.6%). All animals were converted to sinus rhythm with external shock. All received the full infusion protocol, and all survived. No animals had any further arrhythmias or other adverse events. There was no association between occurrence of VF and any particular infusion protocol, suggesting that the high frequency at the start of the study was caused by the learning curve and not the actual procedure.

The inflammatory response to the gene transfer vector is another safety issue to consider. To avoid confusing inflammation caused by β-galactosidase expression (a non-native protein) with that from the viral vectors, we evaluated inflammatory response in the animals receiving the null vectors. For all Ad-null and AAV-null treated animals, we observed only a minimal, perivascular infiltrate of mononuclear cells without damage to adjacent myocytes (Figure 5). There was no diffusion of inflammatory cells into the interstitium, myocyte degeneration or necrosis.

Figure 5.

Microscopic section of Ad-null infused heart shows minimal perivascular inflammatory infiltrate without damage to adjacent myocytes.

4. Discussion

Difficulty in delivering genes homogeneously to the myocardium has been a continuing challenge. Essentially, virus-mediated gene transfer must overcome antiviral protective mechanisms that have evolved continuously over time. In order to better understand these mechanisms, we propose a model with 3 barriers to delivery: (1) vascular dynamics (i.e. broad delivery to the local capillary layer); (2) the vascular endothelial barrier and the extracellular matrix; (3) local virus-myocyte interactions. Each of these steps is a challenge to successful gene transfer. Our previous work built this model through investigation of in vitro and ex vivo parameters [11–13]. The current work shows that similar obstructions are part of the in vivo environment. Understanding and devising ways around these barriers allowed gene transfer to 78% of myocytes in an expanded target region.

4.1. Reaching the local capillary level

Inhibition to gene transfer at a vascular level comes from alterations in flow or pressure that redirect the vector away from the target. We previously showed in ex vivo perfused rabbit hearts that gene transfer efficiency correlated with coronary flow at lower flow rates and then plateaued at higher flow rates, until a destructive level of coronary flow was reached [11]. Emani found a similar response in vivo in rabbit and pig models [18]. Likewise, Champion showed the importance of transmyocardial pressure gradient in mice [21]. Gene transfer was minimal when the coronary and myocardial pressures equalized and improved when the coronary pressure remained above the myocardial pressure. Taken together, these results demonstrate that minimum levels of coronary flow and pressure are needed to fill the entire microvasculature with virus-containing solution. Further increases in flow/pressure probably cause microvascular dilation and more efficient distribution of virus within the capillary layer, but excessive flow or pressure is damaging.

Additional studies applied these observations to innovative methods of traversing the vascular barrier. Boekstegers improved gene transfer with perfusion of virus through the coronary veins during ischemic blockage of the coronary arteries [22]. Similarly, Hayase showed improvement with antegrade intracoronary perfusion during coronary venous blockade [23], and Logeart showed that gene transfer efficiency in a rabbit model could be improved by coronary venous infusion of saline during antegrade delivery of virus into the coronary artery [24].

The major finding of the current work is gene transfer to approximately 80% of cells in the target zone by combining antegrade and retrograde perfusion of vector. The overall size of the target area also increases with this delivery method, essentially combining the target regions of the individual LAD or GCV perfusions while improving the percentage of cells expressing the transgene within the region. This result improves on all previous reports of coronary catheter-based delivery and of delivery to large mammals. Unlike previous reports, our use of bidirectional flow avoided the need for any coronary arterial or venous blockage or ischemia. Importantly, the success of this method requires artery-vein pairs. It is not yet clear how this method could be applied to the right ventricle where much of the venous drainage occurs through the besian veins, and it will require further investigation to determine efficacy of perfusion from large proximal veins (i.e. simultaneous perfusion of the left main and proximal coronary sinus).

A difference between the current report and either our previous Langendorff results or the in vivo Emani results, is that the current study did not find significant improvement with increased coronary arterial flow. We speculate that a limitation imposed by the use of small bore angioplasty catheters in the current study prevented us from achieving the levels of coronary flow that would have shown beneficial effects on gene transfer. Improvement in catheter design could overcome this limitation.

4.2. The endothelial barrier

After reaching the microvascular level, the virus must next cross the endothelial barrier to reach the target cells. In the Langendorff-perfused rabbit model, we showed that permeabilizing the endothelium with serotonin, bradykinin, or hypocalcemia increased gene transfer efficiency. Greelish and Logeart verified the permeability concept using histamine in dog hind-limb and rabbit Langendorff models, respectively [19,24]. Subsequently, numerous agents have been used to achieve the same effect, including VEGF, nitroglycerin, nitroprusside, and substance P, among others [13,16,25,26].

Limitations of the permeability effect were identified by Logeart and Wright, who found no improvement in gene transfer with a variety of permeabilizing agents [27,28]. In general, these studies only gave the permeabilizing agents for short periods of time, and the delivery of permeabilizing agents was not contiguous with the vector administration. Lehnart showed that the permeabilizing effect is lost if it is discontinuous with virus delivery [29], and several authors have investigated the necessary exposure time for permeabilization [30–32]. In general, histamine, bradykinin and serotonin require several minutes for peak efficacy. VEGF has peak efficacy 3–5 minutes after exposure is initiated.

The current work sequentially examines the utility and dose effects of permeabilizing agents. We used a combination of agents to minimize side-effects of any individual agent. We limited our investigation to drugs that were previously shown to have rapid action, and we continued the permeability treatment through the delivery process. With this approach, we demonstrated that the peak effect is achieved with oral administration of a phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor, and infusion of 0.5 μg/ml VEGF, 250 mg/ml TNG, in 0.05mM calcium. The absence of a response to cGMP administration was surprising. We did not investigate this finding, but we hypothesize that inhibition of phosphodiesterase had the same effect as exogenous administration of cGMP, so that the cGMP effect was already maximized by the sildenafil administration prior to cGMP infusion. Since oral delivery of the phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor was benign and of previously established benefit [13], we did not investigate delivery in the absence of sildenafil.

4.3. Virus choice

The current work is the first to evaluate different vectors in the same model, using as much of a “head-to-head” comparison as possible. To some extent, this comparison is artificial due to the vast differences between vectors. The particle size, genome, virus receptor, and replication cycle of Ad and AAV are vastly different. Still, comparison of the two vectors has utility because much of the developmental work in gene therapy uses the adenovirus vector, due to ease of production and use. With the poor long-term expression and inflammatory characteristics of adenoviruses, many investigators switch to AAV when results show promise. After controlling for the total amount of virus delivered, and leaving adequate time for gene expression with the two vectors, we found that adenovirus outperformed AAV. Of course, these are acute expression results. If we had waited 6 months, presumably either AAV serotype would have beaten the adenovirus, since Ad expression would have ceased by that time. The point of this comparison was to guide investigators who are switching from adenoviruses to AAV. Our results show that either AAV serotype will give lower levels of expression, which should be anticipated prior to making a switch. With respect to which AAV serotype to choose, we found that AAV-6 outperformed AAV-2 in the porcine heart.

4.4. Translation to human delivery

The major goal for gene delivery is to devise a method that is safe and effective in humans. Important issues include scalability, tolerance, and ease of administration. Here, we report a method using readily available equipment that could eventually be translated to routine use in the catheterization laboratory. The total amount of virus used in these studies is within the range of other intracoronary perfusion studies that did not achieve this level of gene transfer.[25,33,34] The major negative effects observed with this delivery method were decreases in heart rate and blood pressure from the vasodilating agents and a 5% incidence of ventricular arrhythmias during delivery. The frequency of ventricular arrhythmias is a limitation of using the porcine model. The frequency in our study was not different than the 4.3% incidence with pig catheterization reported by Varenne, and it is consistent with reports of VF incidence in pigs dating back several years. Johanssen showed that pigs have a 4.3% incidence of spontaneous ventricular arrhythmias during the mild stress of movement into a research lab environment and almost 50% incidence with severe physical or emotional stress, suggesting that the ventricular arrhythmia incidence is intrinsic to any porcine model [35, 36] There were no long term adverse events in this study. Further investigation will be needed to define the extent of non-target gene transfer using this intracoronary perfusion method and to determine efficacy in a model comparable to elderly humans with diseased hearts (the likely population for many gene therapy applications). In a separate publication, we have shown that delivery of a functional gene with the LAD/GCV method results in therapeutic effects [37]. From all available data, our method appears to be safe and transferable to the standard coronary catheterization environment.

In conclusion, we have shown the key role of VEGF, TNG, adenosine, and participation of the GCV for improving gene transfer to the large mammal heart. Optimization of these parameters allowed gene transfer to approximately 80% of cells within the target zone of the porcine heart. These finding represent the next step toward the eventual goal of successful application to humans.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by the National Institutes of Health and the American Heart Association

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Guzman RJ, Lemarchand P, Crystal R, Epstein SE, Finkel T. Efficient gene transfer into myocardium by direct injection of adenovirus vectors. Circ Res. 1993;73:1202–7. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.6.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giordano FJ, Ping PP, McKirnan MD, Nozaki S, DeMaria AN, Dillmann W, et al. Intracoronary gene transfer of fibroblast growth factor-5 increases blood flow and contractile function in an ischemic region of the heart. Nature Medicine. 1996;2:534–9. doi: 10.1038/nm0596-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weig H, Laugwitz K, Moretti A, Kronsbein K, Stadele C, Bruning S, et al. Enhanced cardiac contractility after gene transfer of V2 vasopressin receptors in vivo by ultrasound-guided injection or transcoronary delivery. Circulation. 2000;101:1578–85. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.13.1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kikuchi K, McDonald AD, Sasano T, Donahue JK. Targeted Modification of Atrial Electrophysiology by Homogeneous Transmural Atrial Gene Transfer. Circulation. 2005;111:264–70. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000153338.47507.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lamping K, Rios CD, Chun JA, Ooboshi H, Davidson BL, Heistad D. Intrapericardial administration of adenovirus for gene transfer. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:H310–H317. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.1.H310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hajjar R, Schmidt U, Matsui T, Guerrero L, Lee K, Gwathmey J, et al. Modulation of ventricular function through gene transfer in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5251–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maurice J, Hata J, Shah A, White D, McDonald P, Dolber P, et al. Enhancement of cardiac function after adenoviral-mediated in vivo intracoronary beta2-adrenergic receptor gene delivery. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:21–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI6026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davidson M, Jones J, Emani S, Wilson K, Jaggers J, Koch W, et al. Cardiac gene delivery with cardiopulmonary bypass. Circulation. 2001;104:131–3. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.104.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bridges C, Burkman J, Malekan R, Konig S, Chen H, Yarnall C, et al. Global cardiac specific transgene expression using cardiopulmonary bypass with cardiac isolation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73:1939–46. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)03509-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ikeda Y, Gu Y, Iwanaga Y, Hoshijima M, Oh S, Giordano F, et al. Restoration of deficient membrane proteins in the cardiomyopathic hamster by in vivo cardiac gene transfer. Circulation. 2002;105:502–8. doi: 10.1161/hc0402.102953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donahue JK, Kikkawa K, Johns D, Marban E, Lawrence J. Ultrarapid, highly efficient viral gene transfer to the heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4664–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donahue JK, Kikkawa K, Thomas AD, Marban E, Lawrence J. Acceleration of widespread adenoviral gene transfer to intact rabbit hearts by coronary perfusion with low calcium and serotonin. Gene Therapy. 1998;5:630–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagata K, Marban E, Lawrence J, Donahue JK. Phosphodiesterase inhibitor-mediated potentiation of adenovirus delivery to myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:575–80. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiao X, Li J, Samulski R. Production of high-titer recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors in the absence of helper virus. J Virol. 1998;72:2224–32. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.2224-2232.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rutledge E, Halbert C, Russell D. infectious clones and vectors derived from adeno-associated virus (AAV) serotypes other than AAV type 2. J Virol. 1998;72:309–19. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.309-319.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donahue JK, Heldman A, Fraser H, McDonald A, Miller J, Rade J, et al. Focal modification of electrical conduction in the heart by viral gene transfer. Nature Med. 2000;6:1395–8. doi: 10.1038/82214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weiss D, Liggitt D, Clark J. Histochemical discrimination of endogenous mammalian b-galactosidase activity from that resulting from lac-Z gene expression. Histochem J. 1999;31:231–6. doi: 10.1023/a:1003642025421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Emani S, Shah A, Bowman M, Emani S, Wilson K, Glower D, et al. Catheter-based intracoronary myocardial adenoviral gene delivery: importance of intraluminal seal and infusion flow rate. Mol Ther. 2003;8:306–13. doi: 10.1016/s1525-0016(03)00149-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greelish J, Su L, Lankford E, Burkman J, Chen H, Konig S, et al. Stable restoration of the sarcoglycan complex in dystrophic muscle perfused with histamine and a recombinant adeno-associated virus vector. Nature Med. 1999;5:439–43. doi: 10.1038/7439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huxley V, Williams D. Basal and adenosine-mediated protein flux from isolated coronary arterioles. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:H1099–H1108. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.3.H1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Champion H, Georgakopoulos D, Haldar S, Wang L, Wang Y, Kass D. Robust adenoviral and adeno-associated viral gene transfer to the in vivo murine heart. Circulation. 2003;108:2790–7. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000096487.88897.9B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boekstegers P, von Degenfeld G, Giehrl W, Heinrich D, Hullin R, Kupatt C, et al. Myocardial gene transfer by selective pressure-regulated retroinfusion of coronary veins. Gene Ther. 2000;7:232–40. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayase M, del Monte F, Kawase Y, MacNeill B, McGregor J, Yoneyama R, et al. Catheter-based antegrade intracoronary viral gene delivery with coronary venous blockade. Am J Physiol. 2005;288:H2995–H3000. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00703.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Logeart D, Hatem S, Rucker-Martin C, Chossat N, Nevo N, Haddada H, et al. Highly efficient adenovirus-mediated gene transfer to cardiac myocytes after single-pass coronary delivery. Hum Gene Ther. 2000;11:1015–22. doi: 10.1089/10430340050015329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roth D, Lai N, Gao M, Fine S, McKirnan M, Roth D, et al. Nitroprusside increases gene transfer associated with intracoronary delivery of adenovirus. Hum Gene Ther. 2004;15:989–94. doi: 10.1089/hum.2004.15.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iwatate M, Gu Y, Dieterle T, Iwanaga Y, Peterson K, Hoshijima M, et al. In vivo high-efficiency transcoronary gene delivery and Cre-LoxP gene switching in the adult mouse heart. Gene Ther. 2003;10:1814–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Logeart D, Hatem S, Hermburger M, Le Roux A, Michel J, Mercadier J. How to optimize in vivo gene transfer to cardiac myocytes: mechanical or pharmacological procedures? Hum Gene Ther. 2001;12:1601–10. doi: 10.1089/10430340152528101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wright M, Wightman L, Lilley C, de Alwis M, Hart S, Miller A, et al. In vivo myocardial gene transfer: optimization, evaluation and direct comparison of gene transfer vectors. Basic Res Cardiol. 2001;96:227–36. doi: 10.1007/s003950170053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lehnart S, Donahue JK. Coronary perfusion cocktails for in vivo gene transfer. In: Metzger JM, editor. Cardiac Cell and Gene Transfer: principles, protocols, and applications. Vol. 219. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. Methods in Molecular Biology; 2003. pp. 213–218. Walker, JM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu HM, Huang Q, Yuan Y, Granger HJ. VEGF induces NO-dependent hyperpermeability in coronary venules. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:H2735–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.6.H2735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Breil I, Koch T, Belz M, Vanackern K. Effects of bradykinin, histamine and serotonin on pulmonary vascular resistance and permeability. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 1997;159:189–98. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.1997.549324000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mullins RJ, Malias MA, Hudgens RW. Isoproterenol inhibits the increase in microvascular membrane permeability produced by bradykinin. J Trauma. 1989;29:1053–63. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198908000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suzuki G, Lee T, Fallavollita J, Canty J. Adenoviral gene transfer of FGF-5 to hibernating myocardium improves function and stimulates myocytes to hypertrophy and reenter the cell cycle. Circ Res. 2005;96:767–75. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000162099.01268.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lai N, Roth D, Gao M, Tang T, Dalton N, Lai Y, et al. Intracoronary adenovirus encoding adenylyl cyclase VI increases left ventricular function in heart failure. Circulation. 2004;110:330–6. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000136033.21777.4D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Varenne O, Gerard R, Sinnaeve P, Gillijns H, Collen D, Janssens S. Percutaneous adenoviral gene transfer into porcine coronary arteries: is catheter-based gene delivery adapted to coronary circulation? Hum Gene Ther. 1999;10:1105–15. doi: 10.1089/10430349950018102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johansson G, Jonsson L, Lannek N, Blomgren L, Lindberg P, Poupa O. Severe stress-cardiopathy in pigs. Am Heart J. 1974;87:451–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(74)90170-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sasano T, McDonald AD, Kikuchi K, Donahue JK. Molecular ablation of ventricular tachycardia after myocardial infarction. Nat Med. 2006;12:1256–8. doi: 10.1038/nm1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]