Abstract

During cardiac ischaemia antiarrhythmic n–3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) are released following activation of phospholipase A2, if they are in the diet prior to ischaemia. Here we show a positive lusitropic effect of one such PUFA, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) in the antiarrhythmic concentration range in Langendorff hearts and isolated rat ventricular myocytes due to activation of protein kinase A (PKA). Several different approaches indicated activation of PKA by EPA (5–10 μmol l−1): the time constant of decay of the systolic Ca2+ transient decreased to 65.3 ± 5.0% of control, Western blot analysis showed a fourfold increase in phospholamban phosphorylation, and PKA activity increased by 21.0 ± 7.3%. In addition myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity was reduced in EPA; this too may have resulted from PKA activation. We also found that EPA inhibited L-type Ca2+ current by 38.7 ± 3.9% but this increased to 63.3 ± 3.4% in 10 μmol l−1 H89 (to inhibit PKA), providing further evidence of activation of PKA by EPA. PKA inhibition also prevented the lusitropic effect of EPA on the systolic Ca2+ transient and contraction. Our measurements show, however, PKA activation in EPA cannot be explained by increased cAMP levels and alternative mechanisms for PKA activation are discussed. The combined lusitropic effect and inhibition of contraction by EPA may, respectively, combat diastolic dysfunction in ischaemic cardiac muscle and promote cell survival by preserving ATP. This is a further level of protection for the heart in addition to the well-documented antiarrhythmic qualities of these fatty acids.

Fatty acids are released in cardiac muscle during periods of ischaemia due to stress-induced activation of phospholipase A2 (PLA2) (Ford et al. 1991; Hazen et al. 1991; McHowat et al. 1998). The kind of fatty acid released depends ultimately on their presence in the diet. A diet rich in fish oils leads to incorporation of n–3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) into the phospholipid substrate for PLA2 and their subsequent release during ischaemia (Nair et al. 1999), and also reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease. Following myocardial infarct, one oily fish meal per week reduces the risk of a second cardiac event by up to 50% (Kris-Etherton et al. 2002). It is thought this is due, at least in part, to antiarrhythmic properties of n–3 PUFAs. These fatty acids reduce electrical excitability of the cell (Kang et al. 1995). It has been shown that Na+ current (Xiao et al. 1995, 2001), L-type Ca2+ current (Xiao et al. 1997; Negretti et al. 2000) and transient outward current (Macleod et al. 1998) are inhibited by micromolar concentrations of the n–3 PUFA eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), resulting in reduced electrical excitability. In addition, many arrhythmias are thought to result from spontaneous Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) and the consequent activation of Na+–Ca2+ exchange (Capogrossi et al. 1987). This produces depolarising current that may trigger an action potential. The n–3 PUFAs also inhibit the mechanism responsible for SR Ca2+ release (Negretti et al. 2000) via direct inhibition of the release channel (Swan et al. 2003). Thus, one of the mechanisms for producing spontaneous action potentials is reduced in frequency and a larger trigger is required.

n–3 PUFAs ought also to have effects via intracellular signalling pathways that can alter cardiac contractility and affect diastolic function in ischaemic hearts. Many protein kinases are inhibited by n–3 PUFAs, e.g. calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaM kinase II), protein kinase C (PKC), MAPK as well as protein kinase A (PKA) (Mirnikjoo et al. 2001). However, the case with PKA is complicated as phosphodiesterase is also inhibited, allowing cAMP levels to rise (Picq et al. 1996). Given this, it is difficult to predict whether PKA will be activated or inhibited. In the context of myocardial ischaemia, however, the contractile function of the heart is compromised, leading to diastolic dysfunction. Any changes in PKA activity, and e.g. phospholamban phosphorylation, would clearly be of importance to the degree of diastolic dysfunction.

Here, we report experiments that show activation of the PKA pathway by application of the n–3 PUFA EPA. We propose this may have two beneficial effects: (i) a positive lusitropic effect will help to reduce diastolic dysfunction during ischaemia, and (ii) a reduction of myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity may promote cell survival in ischaemia by preserving ATP.

Methods

Rat ventricular myocytes were isolated using a collagenase and protease technique as previously described (Eisner et al. 1989). Adult male Wistar rats were killed by stunning and cervical dislocation. For intracellular Ca2+ measurements, cells were loaded with the membrane-permeant form of Indo-1 at 5 μmol l−1 for 10 min; a period of 20 min was allowed for de-esterification. Cells were placed in a superfusion chamber on the stage of an inverted microscope. Indo-1 fluorescence was excited at 360 nm, and recorded at 400 and 500 nm (O'Neill & Eisner, 1990) using epi-fluorescence optics. All voltage- and current-clamp experiments were carried out with the perforated patch-clamp technique (Horn & Marty, 1988) and voltage-clamp experiments used the switch-clamp mode of the Axoclamp 2A amplifier (Axon Instruments). Pipettes were filled with the following solution (mmol l−1): KCH3O3S, 125; KCl, 20; NaCl, 10; Hepes, 10; MgCl2, 5; K2EGTA, 0.1; titrated to pH 7.2 with KOH, and a final concentration of amphotericin B of 240 μg ml−1.

The bathing solution was as follows (mmol l−1): NaCl, 134; KCl, 4; Hepes, 10; glucose, 11; MgCl2, 1; CaCl2, 1; titrated to pH 7.4 with NaOH. Solutions with 50% Na+ content had 67 mmN-methyl-d-glucamine added to replace Na+. EPA was prepared in ethanol as a 33 mmol l−1 stock solution and stored under a N2 atmosphere for up to 1 week. Fatty-acid-free bovine serum albumin was added (2 mg ml−1) to the washout solution to ensure rapid and complete removal of fatty acid from the solution (Kang & Leaf, 1994; Kang et al. 1995). In voltage-clamp experiments, the holding potential was −40 mV and cells were depolarized for 200 ms to 0 mV at 0.5 Hz, the bathing solution contained 5 mmol l−1 4-aminopyridine and 0.1 mmol l−1 BaCl2 to inhibit outward currents. The use of H89 caused a substantial reduction in the L-type Ca2+ current, to retain a large enough current for analysis, we raised external Ca2+ to 3 mmol l−1.

Preparation of cardiac tissue for PKA assay and cAMP measurements

Langendorff hearts were perfused with the solution (mmol l−1): NaCl, 134; KCl, 4; Hepes, 10; glucose, 11; MgCl2, 1.2; CaCl2, 1; titrated to pH 7.4 with NaOH, used as control. Hearts were perfused with control solution, EPA (10 μmol l−1) or isoprenaline (1 μmol l−1) at 37°C. Left ventricular pressure was measured using a balloon in the left ventricle attached to a pressure transducer, the frequency was set at 4 Hz by stimulating electrodes in the left ventricular wall. After 20 min perfusion (sufficient for the positive lusitropic effect of EPA and isoprenaline to be observed) tissue was taken for PKA and cAMP determinations. (1) 1 g of heart tissue was homogenized in 5 ml of cold extraction buffer (25 mmol l−1 Tris HCl at pH 7.4, 0.5 mmol l−1 EDTA, 0.5 mmol l−1 EGTA, 10 mmol l−1β-mercaptoethanol, 1 μg ml−1 leupeptin, 1 μg ml−1 aprotinin, 200 mmol l−1 phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF)).The lysate was centrifuged for 5 min at 600 g (4°C) and the supernatant saved. The supernatant was taken and PKA activity was determined by a spectrophotometric assay (Roskoski, 1983). (2) Heart tissue was cut in fine pieces; weighed and 10 μl of 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX; 100 μm) was added. Heart samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen. Frozen samples were ground to a fine powder and homogenized in 10 vol. 0.1 m HCl, centrifuged at 600 g and assayed immediately. cAMP was measured using a direct cyclic AMP enzyme immunoassay kit (Assay Designs). A standard cAMP curve was fitted using a four-parameter logistic equation (Sigmaplot 10 program).

Tissue preparation for Western blots

SR vesicles were isolated from tissue harvested as above for Western blot analysis (Korge & Campbell, 1995). SR preparation was lysed in 150 μl of ice-cold RIPA buffer (1× PBS, 1% Igepal, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) with freshly added protease and phosphatase inhibitors (100 μg ml−1 PMSF, 10 μg ml−1 aprotinin, 2 mmol l−1 sodium orthovanadate), incubated on ice for 30 min and centrifuged at 15 000 g for 20 min at 4°C.

Total protein concentrations were measured by Bradford's method. Whole cell lysate (60 μg) was added to 10 μl of 5× electrophoresis sample buffer and separated by SDS/PAGE under reducing conditions on a 15% separation gel with a 4% stacking gel in a Miniprotean II camera (Bio-Rad).

Proteins were electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (16 h, 4°C). Unspecific binding was blocked by incubation in Blotto buffer (1×TBS, 5% nonfat milk and 0.05% Tween 20). Proteins in the membrane were then immunoblotted with antibodies Anti-Phospholamban Phospho-Specific (Ser16; Calbiochem), according to the manufacturer's protocols.

Blots were incubated in a chemiluminescence reagent (Pierce) according to data sheet and exposed to a K-Omat X-ray film (Kodak). The densities of the bands were evaluated using Quantity One software in a G-800 Densitometer (Bio-Rad).

All experiments in the UK were done at room temperature (25°C) and in accordance with the Animal Scientific Procedures Act (1986). All experiments in Venezuela were done according to guidelines of the Universidad Central de Venezuela. All statistics quoted are means ±s.e.m. Student's t tests (one- and two-tailed, where appropriate) were used to test significance.

Results

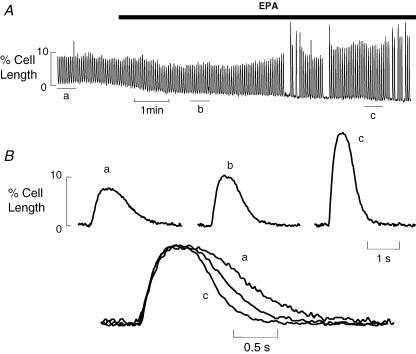

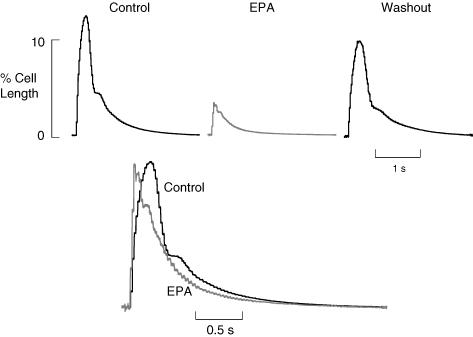

The lusitropic effect of EPA is shown in Fig. 1. Figure 1A shows a slow timebase cell length record of a single ventricular myocyte under field stimulation. As EPA (10 μmol l−1) washes in cell contraction amplitude increases, longer exposures to EPA lead to a decline in amplitude (not shown). Towards the end of the record contraction fails several times indicating reduced electrical excitability of the cell (Kang et al. 1995). In Fig. 1B, averaged records (n= 5) are shown from points indicated by the letters, when these are normalized and superimposed below it is clear that cell relaxation becomes faster in EPA. The remaining experiments in this paper were designed to investigate the possible role of PKA in this positive lusitropic effect of EPA.

Figure 1. Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) increases the rate of relaxation of field stimulated cardiac myocytes.

A, slow timebase record of field stimulated cell shortening from a single rat ventricular myocyte, EPA (10 μmol l−1) was applied as indicated by the bar. B, averaged records from A for the times indicated by letters (n= 5); these are shown normalized for amplitude and superimposed below.

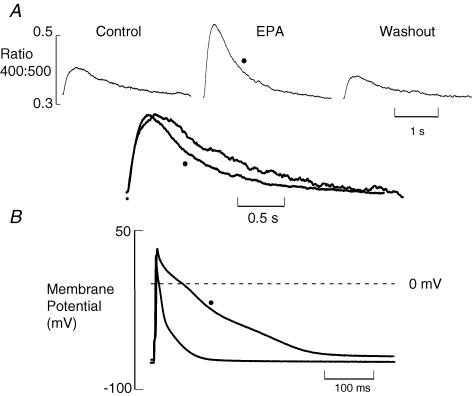

We firstly examined the effect of EPA on the Ca2+ transient responsible for contraction. Figure 2 shows an experiment under current-clamp conditions. The upper part of Fig. 2A shows Ca2+ transients obtained in control, EPA (5 μmol l−1) and after washout. There is a clear reversible increase of Ca2+ transient amplitude. It is also clear from the normalized and superimposed traces that in EPA the transient falls more rapidly. The time constant of decay decreased to 65.3 ± 5.0% of control (P < 0.0001, n= 10). In Fig. 2B, action potentials measured at the same time as the Ca2+ transients are shown superimposed. As has been shown previously (Macleod et al. 1998), EPA increases action potential duration. This is probably responsible for the increased Ca2+ transient amplitude, but seems unlikely to cause a faster fall of Ca2+.

Figure 2. EPA increases the amplitude and rate of fall of the systolic Ca2+ transient.

A, averaged Indo-1 fluorescence ratios before, during and after EPA (5 μmol l−1) application (n= 10). Below control and EPA records are shown normalized for amplitude and superimposed. B, current-clamp records showing averaged action potentials (n= 10) in control and in EPA (•).

One explanation for the faster fall of Ca2+ is activation of PKA, phosphorylation of phospholamban and greater activation of the SR Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA). To determine whether this is so we applied EPA (10 μmol l−1) to Langendorff-perfused hearts. Figure 3A shows left ventricular developed pressure in control (left) and in EPA (right). The developed pressure is greater and falls faster in EPA; this was seen in all 10 hearts studied. (See Table 1)

Figure 3. EPA accelerates relaxation, raises phospholamban phosphorylation and increases PKA activity.

A, left ventricular developed pressure under control conditions (top) and in 10 μmol l−1 EPA. B, typical Western blot of phospholamban phosphorylated at Ser16 from SR vesicles isolated from different hearts perfused with Tyrode solution (control), EPA 10 μmol l−1 or isoprenaline (Iso; 1 μmol l−1). Mean band intensities are: for control, 7.4 ± 2.2 densitometric units (μg protein)−1 (n= 7); EPA, 32.8 ± 8.8 (10 μm; P < 0.01, n= 10); and isoprenaline, 89.9 ± 12.5 (1 μm; P < 0.01, n= 3). C, time-dependent reduction in NADH absorbance as PKA releases ADP in control (⋄), in EPA (10 μmol l−1, ▪) and isoprenaline (1 μmol l−1, ▵).

Table 1.

Developed pressure and rate constants of relaxation measured in Langendorff-perfused hearts in control and EPA (10 μM; n= 10) or isoprenaline (1 μM; n= 5)

| Control | EPA | Control | Isoprenaline | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Developed pressure (mmHg) | 90.2 ± 6.3 | 120.7 ± 9.9** | 65.5 ± 6.0 | 103.1 ± 11.7** |

| Rate constant (s−1) | 14.2 ± 2.2 | 21.5 ± 2.0* | 20.3 ± 1.5 | 34.5 ± 2.7* |

P < 0.015

P < 0.02.

If PKA is activated in EPA, phosphorylation of phospholamban may be increased, accelerating SR Ca2+ uptake. To establish whether EPA induces phosphorylation of phospholamban by PKA, we determined phospholamban phosphorylation at Ser16 (the PKA specific site) by Western blot analysis in cardiac vesicles from hearts treated with Tyrode solution (control), EPA or isoprenaline.

The Western blot in Fig. 3B shows that phosphorylation of phospholamban at Ser16 in SR vesicles increases in EPA and in 1 μmol l−1 isoprenaline (positive control). In control, tissue band density was 7.4 ± 2.2 densitometric units μg−1 protein (n= 7); in EPA it was 32.8 ± 8.8 (n= 10, P < 0.01). In isoprenaline, the average density was 89.9 ± 12.5 (n= 3, P < 0.01).

We decided to determine and compare PKA activity in rat hearts in control and after perfusion with EPA once the lusitropic effect developed, using isoprenaline as a positive control in other hearts. A typical example of records obtained for PKA activity is shown in Fig. 3C; both EPA and isoprenaline increased the rate of fall of absorbance in the PKA assay. On average, EPA increased PKA activity by 21.0 ± 7.3% (P= 0.016; n= 11), and activity was increased in isoprenaline by 21.1 ± 9.1% (P= 0.042; n= 11). The control test showed an average activity for PKA of 244 ± 41.3 UI (mg protein)−1 (n= 11).

With such an increase of PKA activity we would expect there also to be an increase of cAMP therefore we set out to measure [cAMP] in the same tissue samples used in Fig. 3C. The values measured were 60.4 ± 7.9 pmol ml−1 (n= 14) in the control, 33.0 ± 5.0 pmol ml−1 (P < 0.01; n= 17) in EPA, and 90.9 ± 14.0 pmol ml−1 (P < 0.02; n= 10) in isoprenaline.

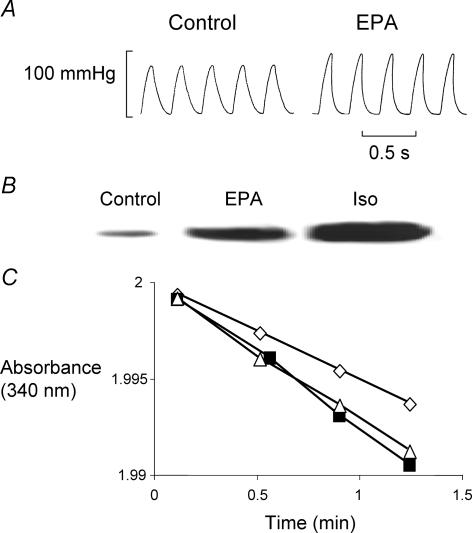

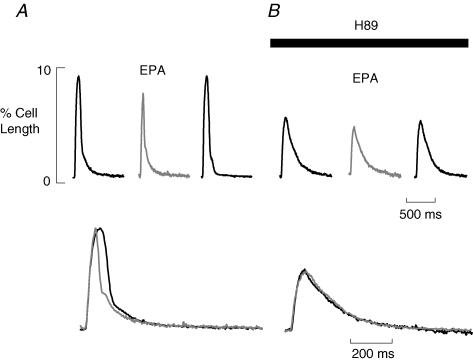

If EPA does indeed activate PKA we should be able to measure other effects of PKA, e.g. an increase of L-type Ca2+ current. Previous work has shown that EPA inhibits L-type Ca2+ channels (Xiao et al. 1997; Negretti et al. 2000) but if EPA also activates PKA leading to more L-type current, the extent of inhibition would appear reduced. In Fig. 4A we see inhibition of L-type current by 5 μmol l−1 EPA; current was reduced by 38.7 ± 3.9% (n= 18). Repeating this in 10 μmol l−1 H89, to inhibit PKA, current inhibition by EPA significantly increased to 63.3 ± 3.4% (n= 12, P < 0.00005). In H89 we raised external Ca2+ to 3 mmol l−1 to compensate for the reduction of L-type current (the current fell in H89 by 72.7 ± 0.8%, n= 2). This extra EPA-dependent inhibition in H89 indicates that activation of PKA by EPA, indeed, increases L-type Ca2+ current.

Figure 4. L-type Ca2+ current inhibition by EPA is increased in the presence of H89.

A, averaged voltage-clamped (stepping from −40 to 0 mV for 200 ms) L-type Ca2+ current records (n= 10) in control, EPA (5 μmol l−1) and after washout with BSA (1 mg ml−1). B, L-type Ca2+ current records in control (n= 12), EPA (5 μmol l−1) and after washout in the presence of 10 μmol l−1 H89 throughout.

In the course of these experiments an interesting anomaly came to light. The Ca2+ measurements in Fig. 2 were made under current clamp. The data in Fig. 5 are systolic Ca2+ transients stimulated by voltage-clamp pulses from −40 to 0 mV for 200 ms. We have shown that EPA reduces contraction amplitude in voltage-clamped rat ventricular myocytes (Negretti et al. 2000) and the Ca2+ transients in Fig. 5A are smaller as expected. However, the superimposed transients after normalization show below that in EPA the fall of the Ca2+ transient is actually slower; the time constant of decay increased by 13.4 ± 3.6% (P < 0.002, n= 23). This does not agree with the effect of EPA on the Ca2+ transient shown in Fig. 2. We should note, however, that the Ca2+ transient amplitude increases under current-clamp or field stimulation but decreases in voltage clamp. We have attempted to take such changes into account in Fig. 5B.

Figure 5. The effect of EPA on the time constant of decay of systolic Ca2+ transient in voltage-clamped cells.

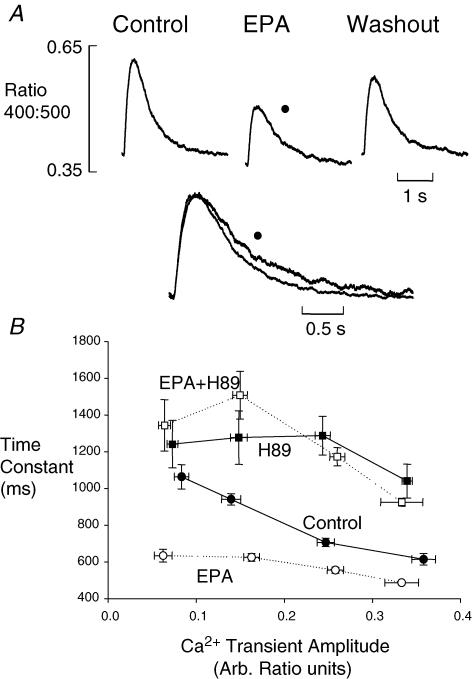

A, averaged records (n= 10) of systolic Ca2+ transients stimulated by depolarising from −40 to 0 mV for 200 ms. Control and EPA (5 μmol l−1) transients are normalized for amplitude and superimposed below. B, time constant of systolic Ca2+ transient as a function of amplitude. •, The time constant of the fall of Ca2+ decreases as amplitude increases. ○, The effect of EPA. The effect of EPA is lost when H89 (10 μmol l−1) is present (□, EPA; ▪, EPA and control; in H89).

The data in Fig. 5B show the relationship between the amplitude of the Ca2+ transient and its time constant of decay. The Ca2+ transient amplitude was varied under voltage clamp by changing the depolarising pulse size. As expected, under control conditions (filled circles) larger transients relax more quickly (Schouten, 1990; Bassani et al. 1995). In 5 μmol l−1 EPA in the same cells as in the control, the curve shifts to shorter time constants at all Ca2+ transient amplitudes. The slopes of the linear regression lines fitted to the raw data (not shown) are different between control and in EPA (P < 0.002) and the time constant of decay is smaller in EPA (P < 1 × 10−6).

Repeating this experiment in H89 to inhibit PKA (open and filled squares represent EPA and control, respectively, in H89) EPA no longer shifts the relationship (P > 0.09); we conclude therefore that the separation in the absence of H89 is due to phosphorylation of phospholamban by PKA. It is also worth noting that H89 alone causes a substantial shift of the curves to longer time constants of decay. This, in addition to the reduction of L-type Ca2+ current by H89, indicates that under normal conditions there is a resting level of PKA activity (also shown in Fig. 3B) that is inhibited by H89.

As mentioned before, under voltage-clamp EPA leads to a slower decay of the Ca2+ transient (Fig. 5A). The experiment in Fig. 6, however, shows, the cell still relaxes faster; in the upper panel, three averaged contractions are shown under voltage clamp. The amplitude is clearly reduced by application of EPA (5 μmol l−1); however, normalization shows that time to peak and relaxation are faster in EPA. Due to the complicated shape of contraction, we could not fit exponentials, so to quantify this effect of EPA we normalized contraction amplitude and calculated the area under the curve. Briefer contractions will have a smaller area, although the increased rate of relaxation will be underestimated due to the more rapid rate of rise of contraction in EPA. On average, this integral decreased to 78.2 ± 8.4% of control (P < 0.05, n= 6). This suggests an additional effect of EPA on the contractile filaments, as faster relaxation results in spite of a slower fall of Ca2+.

Figure 6. EPA shortens contraction even under voltage clamp.

Upper traces, averaged records (n= 10) of cell shortening under voltage clamp. Lower traces, control and EPA (5 μmol l−1; grey) contractions are shown normalized for amplitude and superimposed.

A positive lusitropic effect like that in Fig. 6 should also be sensitive to PKA inhibition. In Fig. 7A, we show the positive lusitropic effect on contraction of EPA in a field-stimulated cell. The increased rate of rise and fall of contraction is clear when control and EPA contractions are normalized and superimposed (below). In Fig. 7B, this protocol is repeated in 10 μmol l−1 H89 to inhibit PKA. As with L-type Ca2+ current (Fig. 4), the contraction is smaller in H89 and EPA inhibits the amplitude further. However, the superimposed traces below show the rates of rise and fall of contraction are no longer affected by EPA. We have quantified this as described above. On average, the contraction integral in EPA alone was reduced to 64.7 ± 2.7% of control (P < 0.0001, n= 6). In H89, EPA produced no significant change, the integral being 103.5 ± 3.1% of that in H89 alone (P > 0.35). We conclude, therefore, that any effect of EPA on the SR or myofilaments has been prevented by inhibiting PKA.

Figure 7. The lusitropic effect of EPA is lost in the presence of H89.

A, averaged cell shortening records (n= 6) in control conditions under field stimulation. B, averaged cell shortening records (n= 6) in the presence of 10 μmol l−1 H89. A and B, the EPA (10 μmol l−1) trace is shown in grey. The traces below in each panel show normalized and superimposed contractions in control and EPA.

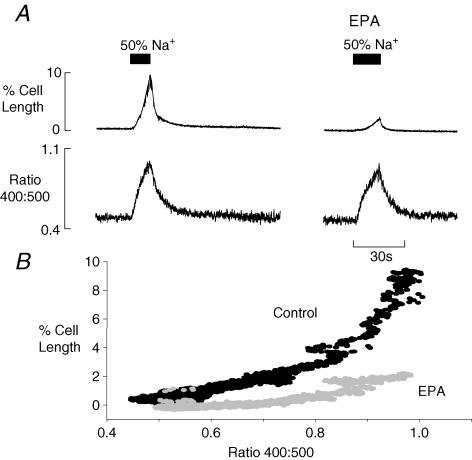

The results of Figs 5A and 6 showing the effect on Ca2+ transients and contractions suggest that myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity is altered in EPA. To demonstrate this, cells were preincubated in ryanodine (1 μmol l−1) to inhibit the SR, and external Na+ was then reduced by 50% to induce an influx of Ca2+ on Na+−Ca2+ exchange. In the left panel of Fig. 8A is the rise of Ca2+ produced by lowering Na+ (signalled by the rise in the Indo-1 ratio) and the resulting contraction above.

Figure 8. EPA reduces myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity.

A, the upper traces show cell shortening records, below are Indo-1 ratio records. The bar indicates that external Na+ was reduced to 50% of control solution concentration. B, the plot shows the relationship between Indo-1 ratio and cell shortening in the absence (control; black symbols) and in presence of EPA (grey symbols).

When this protocol was repeated after 3 min in 10 μmol l−1 EPA, the same rise of Ca2+ produces much less contraction, i.e. myofilament sensitivity to Ca2+ is reduced. The plot in Fig. 8B of cell length as a function of the Indo-1 ratio emphasizes this difference. Similar results were seen in all six cells studied.

Discussion

The antiarrhythmic actions of n–3 PUFAs are well documented: they inhibit various surface membrane ion channels to reduce myocyte electrical excitability (Kang et al. 1995) and, in addition, they inhibit the mechanism responsible for spontaneous release of Ca2+ from the SR (Negretti et al. 2000); Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release. Thus spontaneous action potentials are less likely as they are more difficult to stimulate and one of the triggers is less frequent. However, as we show here, n–3 PUFAs also have other effects that change the contractile behaviour of the cardiac cell. These may be important for improving diastolic function in ischaemic hearts and ensuring cells can survive a period of ischaemia.

Throughout this study, EPA increases the rate of fall of the Ca2+ transient and relaxation of contraction (irrespective of the effect on Ca2+ transient and contraction amplitudes). In intact hearts this is associated with increased phosphorylation of phospholamban at the PKA-specific site and increased PKA activity. Is there any evidence that n–3 PUFAs activate PKA? In fact the literature suggests the opposite; in vitro n–3 PUFAs inhibit the PKA catalytic subunit (Mirnikjoo et al. 2001). However, there is also evidence that n–3 PUFAs inhibit phosphodiesterase (Dubois et al. 1993; Picq et al. 1996) and increase cAMP levels (Picq et al. 1996). Although this should overcome some direct PKA inhibition, it appears not to take place in our study where we find cAMP levels actually fall. However, our measurements show that 10 μmol l−1 EPA increases PKA activity (Fig. 3), so how can this be explained? Recently it has been shown that reactive oxygen species (ROS) can activate PKA by forming a disulphide bridge between cysteine groups linking regulatory subunits together, leading to activation of the kinase (Brennan et al. 2006). Of course, for this to be important here it is necessary that n–3 PUFAs lead to production of ROS and indeed this is the case (Maziere et al. 1999; Arita et al. 2001). Thus, perhaps by acting on mitochondrial respiration, ROS are formed, PKA is activated and the changes of contractile behaviour we report take place. ROS formation may also account for the fall of [cAMP] in EPA as it is known that adenylate cyclase is inhibited by ROS (Persad et al. 1998). Such a sequence of events remains to be confirmed experimentally.

The remaining experiments in this study sought to demonstrate a role for PKA in the positive lusitropic effect of EPA. Phospholamban is an important PKA target protein, and in Fig. 3B we show that EPA increased phospholamban phosphorylation at Ser16 (the PKA-specific site). This would contribute to the positive lusitropic effect of EPA we report.

Phosphorylation of the L-type Ca2+ channel by PKA increases its open probability (Brum et al. 1984) leading to more current. However, EPA also inhibits the L-type Ca2+ channel (Xiao et al. 1997; Macleod et al. 1998; Negretti et al. 2000). This inhibition might disguise the effect of PKA on current amplitude. Our approach to this has been to compare EPA-induced inhibition of L-type current in control and with PKA inhibited. Inhibition of PKA should leave only direct inhibition without any indirect increase of current due to phosphorylation. One problem with this is that H89 reduced L-type current (not shown) perhaps due to loss of baseline phosphorylation of L-type channels or direct inhibition of the channel as has been recently shown in rat myocytes (Bracken et al. 2006). To allow us to compare current inhibition, we raised bathing Ca2+ to 3 mmol l−1 (the inhibition of L-type current by EPA in 3 mmol l−1 Ca2+ is not significantly different from that in 1 mmol l−1 Ca2+; not shown). EPA inhibited about 40% of L-type current in control and over 60% with PKA inhibited (Fig. 4), indicating an increase of L-type current through PKA-dependent channel phosphorylation compensating for some of the direct inhibition by EPA.

One possible complication for this experiment is the selectivity of H89, as it also inhibits other kinases, e.g. CaM kinase II. However, even at the relatively high concentrations used here we would expect only minor inhibition of this enzyme (Chijiwa et al. 1990). Similarly, PK C is inhibited only slightly by 10 μmol l−1 H89 (Chijiwa et al. 1990). It seems fair therefore to conclude that the effects of EPA in H89 differ from those in the absence of H89 due to inhibition of PKA. This also seems fair in the light of the direct measurements of activation of PKA and PKA-dependent phosphorylation (Fig. 3) we also report.

The evidence so far suggests PKA is activated in the presence of EPA, why then, is the rate of decay of the Ca2+ transient reduced in voltage clamp (Fig. 5) and increased when the action potential stimulates contraction (Fig. 2)? One obvious difference is that the Ca2+ transient amplitude is reduced in voltage clamp, but increases in current clamp (cf. Figs 5 and 2). Underlying this are the electrophysiological effects of EPA. Under voltage clamp, the negative inotropic effect follows inhibition of L-type current whereas under current clamp the longer action potential leads to a larger Ca2+ transient. One consequence of a smaller Ca2+ transient would be reduced activation of CaM kinase II, as less activating Ca2+ would be bound to calmodulin. CaM kinase II also phosphorylates phospholamban increasing SERCA activity (Le Peuch et al. 1979). Here again, we have two counteracting effects: increased PKA-dependent phosphorylation of phospholamban and a probable decrease of CaM-kinase-II-dependent phosphorylation. In order to distinguish between these effects, we compared the rate of decay of the Ca2+ transient over a range of amplitudes. In this way we hoped to remove Ca2+ transient amplitude as a variable. In Fig. 5B, we see that in EPA the time constant of decay is smaller at all Ca2+ transient amplitudes, i.e. Ca2+ falls faster than in the control. This shows the effect of EPA on PKA activity without the confusing influence of altering Ca2+ transient amplitude. The second approach we made to this question was simply to inhibit PKA. As can also be seen in Fig. 5B, in H89 there is almost complete overlap between the points collected in the presence and absence of EPA. Again, a resting level of PKA-dependent phosphorylation is suggested by the upward shift of the curves in H89 in agreement with recent data in rat myocytes (Bracken et al. 2006). We conclude therefore that the lack of a positive lusitropic effect in EPA under voltage clamp, e.g. in Fig. 5A, results from the smaller amplitude of the Ca2+ transient under these conditions. As has been shown earlier (Schouten, 1990; Bassani et al. 1995), the smaller size of the transient reduces its rate of recovery, probably through the level of phosphorylation of phospholamban at the CaM-kinase-II-specific site, although CaM-kinase-II-independent mechanisms may also exist (Valverde et al. 2005).

The final observation we make here relates to myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity. EPA greatly reduces the amount of cell shortening for a given rise of intracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 8). This too, may result from activation of PKA as phosphorylation of troponin I lowers myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity (Zhang et al. 1995). Under physiological conditions this helps allow faster relaxation to accommodate higher frequencies during β-adrenergic stimulation. Under ischaemic conditions, therefore, two effects of n–3 PUFAs, i.e. the faster relaxation we report here and the lower resting [Ca2+]i we have previously reported (O'Neill et al. 2002), could combine to combat diastolic dysfunction during myocardial ischaemia that may develop due, for example, to loss of ATP and consequent slowing of SERCA activity (Halow et al. 1999; Overend et al. 2001).

The benefit of a positive lusitropic effect

Several lines of evidence presented here either suggest (Figs 4, 5 and 7) or show directly (Fig. 3) that EPA causes an activation of PKA. The resulting phosphorylations lead to changes of the contractile properties of the cells that may benefit ischaemic myocardium. The rate of relaxation is increased in the presence of EPA in intact hearts (Fig. 3) and isolated myocytes (Fig. 1). Diastolic dysfunction is an early consequence of myocardial ischaemia, a positive lusitropic effect would benefit the heart by preserving pump function. In addition, reduced myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity would limit energy consumption thereby preserving ATP levels. This might enable the cell to survive a period of ischaemia with less damage. Evidence that reduced Ca2+ sensitivity of the myofilaments might, indeed, be beneficial comes from a study showing that an inhibitor of actin–myosin interaction, BDM, limits the infarct size following coronary artery occlusion (Garcia-Dorado et al. 1992). It is also worth noting that fish oil supplementation of the diet leads to less ischaemic damage following coronary artery ligation in rabbits (Ogita et al. 2003) and reduces the fraction of isolated rat ventricular myocytes that die during simulated ischaemia/reperfusion (Takeo et al. 1998).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by British Heart Foundation Project Grant 02/062/13868 and Universidad Central de Venezuela, Facultad de Medicina, Instituto de Medicina Experimental. (Grant Consejo de Desarrollo Cientifico y Humanistico Proyecto Individual 09-33-5302- 2003 and 09-33-5302- 2005). The authors are very grateful to Dr José Bubis for helpful discussions and technical advice in PKA activity determinations.

References

- Arita K, Kobuchi H, Utsumi T, Takehara Y, Akiyama J, Horton AA, Utsumi K. Mechanism of apoptosis in HL-60 cells induced by n–3 and n–6 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Biochem Pharmacol. 2001;62:821–828. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00723-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassani RA, Mattiazzi A, Bers DM. CaMKII is responsible for activity-dependent acceleration of relaxation in rat ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1995;268:H703–H712. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.268.2.H703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracken N, Elkadri M, Hart G, Hussain M. The role of constitutive PKA-mediated phosphorylation in the regulation of basal I (Ca2+) in isolated rat cardiac myocytes. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;148:1108–1115. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan JP, Bardswell SC, Burgoyne JR, Fuller W, Schroder E, Wait R, Begum S, Kentish JC, Eaton P. Oxidant-induced activation of type I protein kinase A is mediated by RI subunit interprotein disulfide bond formation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:21827–21836. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603952200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brum G, Osterrieder W, Trautwein W. β-Adrenergic increase in the calcium conductance of cardiac myocytes studied with the patch clamp. Pflugers Arch. 1984;401:111–118. doi: 10.1007/BF00583870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capogrossi MC, Houser SR, Bahinski A, Lakatta EG. Synchronous occurrence of spontaneous localised calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum generates action potentials in rat cardiac ventricular myocytes at normal resting membrane potential. Circ Res. 1987;61:498–503. doi: 10.1161/01.res.61.4.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chijiwa T, Mishima A, Hagiwara M, Sano M, Hayashi K, Inoue T, Naito K, Toshioka T, Hidaka H. Inhibition of forskolin-induced neurite outgrowth and protein phosphorylation by a newly synthesized selective inhibitor of cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase, N-[2-(p-bromocinnamylamino) ethyl]-5-isoquinolinesulfonamide (H-89), of PC12D pheochromocytoma cells. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:5267–5272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois M, Picq M, Nemoz G, Lagarde M, Prigent AF. Inhibition of the different phosphodiesterase isoforms of rat heart cytosol by free fatty acids. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1993;21:522–529. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199304000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisner DA, Nichols CG, O'Neill SC, Smith GL, Valdeolmillos M. The effects of metabolic inhibition on intracellular calcium and pH in isolated rat ventricular cells. J Physiol. 1989;411:393–418. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford DA, Hazen SL, Saffitz JE, Gross RW. The rapid and reversible activation of a calcium-independent plasmalogen-selective phospholipase A2 during myocardial ischemia. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:331–335. doi: 10.1172/JCI115296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Dorado D, Theroux P, Duran JM, Solares J, Alonso J, Sanz E, Munoz R, Elizaga J, Botas J, Fernandez-Aviles F. Selective inhibition of the contractile apparatus. A new approach to modification of infarct size, infarct composition, and infarct geometry during coronary artery occlusion and reperfusion. Circulation. 1992;85:1160–1174. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.3.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halow JM, Figueredo VM, Shames DM, Camacho SA, Baker AJ. Role of slowed Ca2+ transient decline in slowed relaxation during myocardial ischemia. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1999;31:1739–1748. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1999.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazen SL, Ford DA, Gross RW. Activation of a membrane-associated phospholipase A2 during rabbit myocardial ischemia which is highly selective for plasmalogen substrate. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:5629–5633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn R, Marty A. Muscarinic activation of ionic currents measured by a new whole-cell recording method. J Gen Physiol. 1988;92:145–159. doi: 10.1085/jgp.92.2.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang JG, Leaf A. Effects of long chain polyusaturated fatty acids on the contraction of neonatal rat cardiac myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:9886–9890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.9886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang JX, Xiao YF, Leaf A. Free, long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids reduce membrane electrical excitability in neonatal rat cardiac myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:3997–4001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korge P, Campbell KB. Regulation of calcium pump function in back inhibited vesicles by calcium-ATPase ligands. Cardiovasc Res. 1995;29:512–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kris-Etherton PM, Harris WS, Appel LJ. Fish consumption, fish oil, omega-3 fatty acids, and cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2002;106:2747–2757. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000038493.65177.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Peuch CJ, Haiech J, Demaille JG. Concerted regulation of cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium transport by cyclic adenosine monophosphate dependent and calcium–calmodulin-dependent phosphorylations. Biochemistry. 1979;18:5150–5157. doi: 10.1021/bi00590a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macleod JC, MacKnight ADC, Rodrigo GC. The electrical and mechanical response of adult guinea pig and rat ventricular myocytes to omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;356:261–270. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00528-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maziere C, Conte MA, Degonville J, Ali D, Maziere JC. Cellular enrichment with polyunsaturated fatty acids induces an oxidative stress and activates the transcription factors AP1 and NFkappaB. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;265:116–122. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHowat J, Liu S, Creer MH. Selective hydrolysis of plasmalogen phospholipids by Ca2+-independent PLA2 in hypoxic ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1998;274:C1727–C1737. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.6.C1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirnikjoo B, Brown SE, Kim HF, Marangell LB, Sweatt JD, Weeber EJ. Protein kinase inhibition by omega-3 fatty acids. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:10888–10896. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008150200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair SS, Leitch J, Falconer J, Garg ML. Cardiac (n–3) non-esterified fatty acids are selectively increased in fish oil-fed pigs following myocardial ischemia. J Nutr. 1999;129:1518–1523. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.8.1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negretti N, Perez MR, Walker D, O'Neill SC. Inhibition of sarcoplasmic reticulum function by polyunsaturated fatty acids in intact, isolated myocytes from rat ventricular muscle. J Physiol. 2000;523:367–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00367.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill SC, Eisner DA. A. mechanism for the effects of caffeine on Ca2+ release during diastole and systole in isolated rat ventricular myocytes. J Physiol. 1990;430:519–536. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill SC, Perez MR, Hammond KE, Sheader EA, Negretti N. Direct and indirect modulation of rat cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum function by n–3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. J Physiol. 2002;538:179–184. doi: 10.1113/j.1469-7793.2001.00179.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogita H, Node K, Asanuma H, Sanada S, Takashima S, Minamino T, Soma M, Kim J, Hori M, Kitakaze M. Eicosapentaenoic acid reduces myocardial injury induced by ischemia and reperfusion in rabbit hearts. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2003;41:964–969. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200306000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overend CL, Eisner DA, O'Neill SC. Altered cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum function of intact myocytes of rat ventricle during metabolic inhibition. Circ Res. 2001;88:181–187. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persad S, Panagia V, Dhalla NS. Role of H2O2 in changing beta-adrenoceptor and adenylyl cyclase in ischemia-reperfused hearts. Mol Cell Biochem. 1998;186:99–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picq M, Dubois M, Grynberg A, Lagarde M, Prigent AF. Specific effects of n–3 fatty acids and 8-bromo-cGMP on the cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase activity in neonatal rat cardiac myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1996;28:2151–2161. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roskoski R., Jr Assays of protein kinase. Methods Enzymol. 1983;99:3–6. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)99034-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schouten VJA. Interval dependence of force and twitch duration in rat heart explained by Ca2+ pump inactivation in sarcoplasmic reticulum. J Physiol. 1990;431:427–444. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan JS, Dibb KM, Negretti N, O'Neill SC, Sitsapesan R. Effects of eicosapentaenoic acid on cardiac SR Ca2+-release and ryanodine receptor function. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;60:337–346. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(03)00545-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeo S, Nasa Y, Tanonaka K, Yabe K, Nojiri M, Hayashi M, Sasaki H, Ida K, Yanai K. Effects of long-term treatment with eicosapentaenoic acid on the heart subjected to ischemia/reperfusion and hypoxia/reoxygenation in rats. Mol Cell Biochem. 1998;188:199–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valverde CA, Mundina-Weilenmann C, Said M, Ferrero P, Vittone L, Salas M, Palomeque J, Vila PM, Mattiazzi A. Frequency-dependent acceleration of relaxation in mammalian heart: a property not relying on phospholamban and SERCA2 a phosphorylation. J Physiol. 2005;562:801–813. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.075432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao YF, Gómez AM, Morgan JP, Lederer WJ, Leaf A. Suppression of voltage-gated L-type Ca2+ currents by polyunsaturated fatty acids in adult and neonatal rat ventricular myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:4182–4187. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.4182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao YF, Kang JX, Morgan JP, Leaf A. Blocking effects of polyunsaturated fatty acids on Na+ channels of neonatal rat ventricular myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:11000–11004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao YF, Ke Q, Wang SY, Auktor K, Yang Y, Wang GK, Morgan JP, Leaf A. Single point mutations affect fatty acid block of human myocardial sodium channel alpha subunit Na+ channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:3606–3611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061003798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R, Zhao J, Mandveno A, Potter JD. Cardiac troponin I phosphorylation increases the rate of cardiac muscle relaxation. Circ Res. 1995;76:1028–1035. doi: 10.1161/01.res.76.6.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]