Abstract

Jimpy (Plpjp) is an X-linked recessive mutation in mice that causes CNS dysmyelination and early death in affected males. It results from a point mutation in the acceptor splice site of myelin proteolipid protein (Plp) exon 5, producing transcripts that are missing exon 5, with a concomitant shift in the downstream reading frame. Expression of the mutant PLP product in Plpjp males leads to hypomyelination and oligodendrocyte death. Expression of our Plp-lacZ fusion gene, PLP(+)Z, in transgenic mice is an excellent readout for endogenous Plp transcriptional activity. The current studies assess expression of the PLP(+)Z transgene in the Plpjp background. These studies demonstrate that expression of the transgene is decreased in both the central and peripheral nervous systems of affected Plpjp males. Thus, expression of mutated PLP protein downregulates Plp gene activity both in oligodendrocytes, which eventually die, and in Schwann cells, which are apparently unaffected in Plpjp mice.

Keywords: Jimpy mouse, Gene regulation, Myelin proteolipid protein, Oligodendrocyte differentiation, Schwann cell, Transgenic mice

Introduction

Dysmyelinating disorders such as Pelizaeus–Merzbacher disease in humans or the jimpy Plp mutation in mice are characterized by dramatically altered oligodendrocyte differentiation and brain function, which result from mutations in the myelin proteolipid protein (Plp) gene [reviewed in 1, 2]. A point mutation in the acceptor splice site of exon 5 in the jimpy Plp gene (Plpjp) results in deletion of this exon from Plp/Dm20 transcripts and a concomitant frameshift and truncation of the C-terminal amino acids [3, 4]. In very young animals, the transcription rate of the Plpjp gene is similar to that in mice containing the wild-type gene. However, as development proceeds, Plp gene transcription in the mutant does not increase as it does in wild-type mice [5]. In addition, the Plpjp mutation exhibits pleiotropic effects, for example, reducing the transcription rate of the myelin basic protein (Mbp) gene, which is expressed later in the oligodendrocyte differentiation pathway. Other point mutations in the Plp gene, resulting in both conservative and non-conservative amino acid substitutions, have been identified, which generally cause developmental disorders that are similar to that caused by the Plpjp mutation [6–8]. On the whole, Plp gene mutations are far more devastating than mutations in other genes that cause dysmyelination. Mice and rats with Plp mutations generally die within 3–4 weeks after birth, while shiverer, quaking and trembler mice survive to adulthood. Mutant PLP proteins tend to accumulate in the endoplasmic reticulum of oligodendrocyte cell bodies [9], and it is proposed that the defective protein activates the unfolded protein response, culminating in oligodendrocyte cell death [10]. The greater lethality of these mutations, however, likely results from expression of mutated PLP in neurons in the brainstem, which leads to dramatic respiratory depression in response to hypoxia [11].

The current studies were designed to investigate the effects of the Plpjp mutation on Plp gene expression in both the CNS and PNS, using a transgenic mouse model in which expression of the lacZ reporter gene is governed by Plp genomic sequences. The PLP(+)Z transgene contains the proximal 2.4 kb of 5′-flanking DNA, exon 1, intron 1 and the first 37 bp of exon 2 of the Plp gene, and encodes a fusion protein between the first 13 amino acids of PLP and β-galactosidase (β-gal), which is trafficked to the myelin membrane [12]. A series of transgenic animals have subsequently been derived that further corroborate the ability of these Plp sequences to promote transgene expression, and to serve as a reliable readout of endogenous Plp gene activity [13–18], with inclusion of Plp intron 1 sequences being important [19]. In the current studies, the PLP(+)Z transgene was crossed into the Plpjp background and used to monitor the effects of the Plpjp mutation on Plp promoter activity via lacZ reporter gene expression.

Methods

Animals

The studies were conducted on transgenic mice that express the Plp-lacZ fusion gene, PLP(+)Z [12]. The transgene encodes a protein containing the first 13 amino acids of PLP fused to β-gal. Male mice, homozygous for the PLP(+)Z transgene (line 26H), were bred to non-transgenic Plpjp female carriers (heterozygous Plpjp females). Thus, all of the resulting progeny were heterozygous for the PLP(+)Z transgene. Genomic DNA was isolated from tail biopsies as previously described [12] and the progeny genotyped by PCR for the presence/absence of the jimpy mutation (Plpjp). PCR primers, derived from sequence flanking the Plpjp point mutation in the acceptor splice site of Plp exon 5, were: Plp intron 4 sense primer [5′-CATGGCCTCTAGCCTTATGAAGTTTAC-3′] and Plp exon 5 antisense primer [5′-CCTCAGCTGTTT TGCAGATGGACAG-3′]. The PCR product generated was 126-bp in length. Since the Plpjp mutation results in loss of a DdeI recognition site, PCR products were digested with DdeI and analyzed by gel electrophoresis. The PCR product amplified from the wildtype Plp allele was cleaved by DdeI, while the Plpjp-derived PCR product was not cleaved. Thus, affected Plpjp males displayed a single band of 126-bp, while wild-type male littermates exhibited two bands migrating as a doublet (approximately 50 bp and 80 bp in size). Heterozygous Plpjp females had both the 126-bp band and the shorter doublet.

β-Galactosidase histochemistry

Cells expressing the PLP(+)Z transgene were identified in tissue sections from mouse brain using β-gal chromogenic substrates (X-gal or Bluogal) as previously described [12], except that 1.0% glutaraldehyde in PBS (pH 7.3) was the fixative. The Bluogal substrate was used for analysis of cryostat sections at high magnification since the blue reaction product does not diffuse out of cells. Thus, better cell morphology can be assessed with this stain.

Immunohistochemistry

Mice at 21 days of age (P21) were perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.6) under halothane anesthesia. Tissues were removed, post-fixed for 24 h in 4% paraformaldehyde and cryoprotected in 20% glycerol. Tissue samples were sectioned on a sliding microtome. Sections (30 μm) were immunostained according to the methods of Bö et al. [20]. Free-floating sections were pretreated in 0.1% OsO4 for 30 s, rinsed well with PBS, and placed in a solution of 1% H2O2 containing 10% Triton X-100 for 30 min. Tissue sections were blocked with 3% normal goat serum in PBS for 30 min and incubated in the following series of solutions: primary antibody diluted in PBS, overnight at 4°C; biotinylated secondary antibodies (Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA) diluted 1:2,000 in PBS for 30 min; enzyme (HRP)-linked biotin (1:1,000) and avidin (1:1,000) (Vector Laboratories) in PBS for 1 h; diaminobenzidine (DAB)/H2O2 for up to 8 min; 0.1% OsO4 for 30 s. Sections were mounted in glycerol. For double-label immunofluorescence, fluorescein- and Texas Red-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch, Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA) were used (diluted 1:1,500 in PBS for 1 h) and the sections mounted in Vectashield mounting media (Vector Laboratories). Primary antibodies included: rabbit anti-PLP (M2) [21] at 1:1,000; rabbit anti-β-gal (Cortex Biochem., San Leandro, CA) at 1:1,000; mouse anti-2′,3′-cyclic nucleotide-3′-phosphodiesterase (CNP; Sternberger Monoclonals Inc., Lutherville, MD) at 1:1,000; mouse anti-myelin basic protein (MBP, Sternberger Monoclonals Inc.) at 1:5,000 and 1:10,000 for Plpjp and wild-type mice, respectively. Primary antibodies used for double-label immunofluorescence were: rabbit anti-PLP (M2) at 1:1000 and mouse anti-β- gal (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) at 1:1,000.

Western blot analysis

Lysates for Western blot analysis comparing proteins from brain and spinal cord were prepared by homogenization of tissues in 4% SDS (1:20 wt:vol). Proteins were fractionated on a 10% polyacrylamide gel (SDS-PAGE) [22] and analyzed using the ECL kit (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ). Blots were incubated with PLP-specific (M2) and β-gal (Cortex) anti-rabbit polyclonal antibodies, overnight at 4°C. The blots were then washed and incubated with secondary antibody at a dilution of 1:5,000 for 2 h at room temperature.

Tissue lysates for Western blot analysis comparing proteins from brain and sciatic nerve were prepared in Lysis Buffer (0.15 M NaCl, 0.05 M Tris, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.05% SDS, pH 7.5) supplemented with protease inhibitors (20 g/ml leupeptin, 100 g/ml aprotinin, 2 mM PMSF, 5 mM NEM). After 1 h on ice, samples were centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 10 min to remove insoluble material. Protein concentration in the supernatants was determined using the bicinchoninic acid method (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Proteins were separated on a 10% polyacrylamide gel (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to a PVDF membrane. The blots were blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk in TBS-T buffer (10 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 0.2% Tween 20, pH 8.0) overnight at 4°C and subsequently incubated with primary rabbit antibody against PLP, β-gal, MBP (Sternberger Monoclonals) or β-actin (Sigma,) for 1 h at room temperature. After washing, the blots were incubated with secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. Immunoreactive bands were visualized using ECL Plus detection reagents (Amersham).

RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated by the procedure of Chomczynski and Sacchi [23]. Reverse transcription (RT) was performed using the SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). PCR primer pairs were (1) Plp/Dm20: sense 5′-CCAAAAACTACCAGGACTA-3′and antisense 5′-TCAGAGACGCGACTACGGT-3′generating products of 459-bp (Plp) and 354-bp (Dm20); (2) lacZ: sense 5′-GTGCGGATTGAAAATGGTCT-3′ and antisense 5′-CACCGCATCAGCAAGTGTAT- 3′generating a 1,500-bp product; (3) ′-tubulin: sense 5′-CGTGAGTGCATCTCCATCCAT-3′ and antisense 5′-GCCCTCACCCACATACCAGTG- 3′ generating a 1,233-bp product.

Results

PLP(+)Z transgene expression in the developing CNS in Plpjp mice

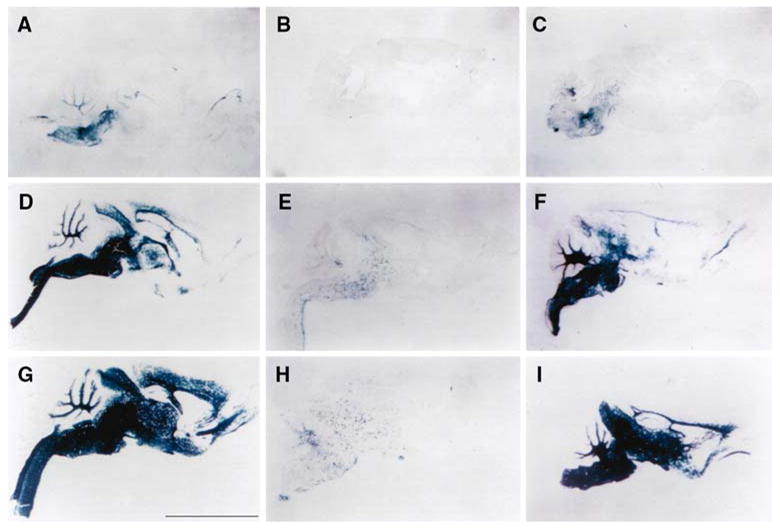

Expression of the PLP(+)Z transgene was evaluated in the Plp dysmyelinating mouse mutant, Plpjp. The transgene contains Plp genomic DNA extending from the proximal 2.4 kb of 5′-flanking DNA, downstream to the first 37 bp of exon 2, which were used to drive expression of a lacZ reporter gene cassette. Thus the transgene contains the Plp promoter as well as a tissue-specific enhancer located in Plp intron 1 DNA [24, 25]. Expression of the PLP(+)Z transgene was evaluated in affected Plpjp males, which express a mutated Plp gene (Plpjp), and compared to that produced in wild-type male littermates containing the normal Plp gene. In some cases, transgene expression was also measured in heterozygous Plpjp female carriers (Plpjp/+). As shown in Fig. 1, expression of the transgene, as determined by X-gal staining, was markedly reduced in the brains of Plpjp males at all ages, when compared to wild-type male littermates. In contrast, heterozygous Plpjp females demonstrated only a slight reduction in β-gal activity when compared to wild-type male littermates, with the anterior cortical regions being affected the most. Throughout the peak period of myelinogenesis, transgene expression in the heterozygous Plpjp females lagged behind that of wild-type littermates. These data are consistent with the known early reduction in Plp gene expression in Plpjp female carriers [26–28], suggesting that the PLP(+)Z transgene is regulated, similarly, in the heterozygous Plpjp background. Thus, the early reduction in Plp gene expression in Plpjp females is likely caused by a reduction in Plp gene transcription.

Fig. 1.

PLP(+)Z transgene expression in brain. Sagittal sections from brains of transgenic mice at postnatal ages 7 days (A, B, C), 14 days (D, E, F), and 21 days (G, H, I) were stained with X-gal to localize β-gal activity. Staining was substantially reduced in Plpjp males (B, E, H) compared to wild-type male littermates (A, D, G) or heterozygous Plpjp females (C, F, I). Bar: 0.5 cm

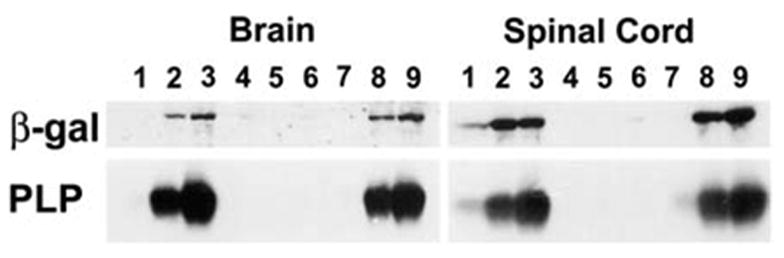

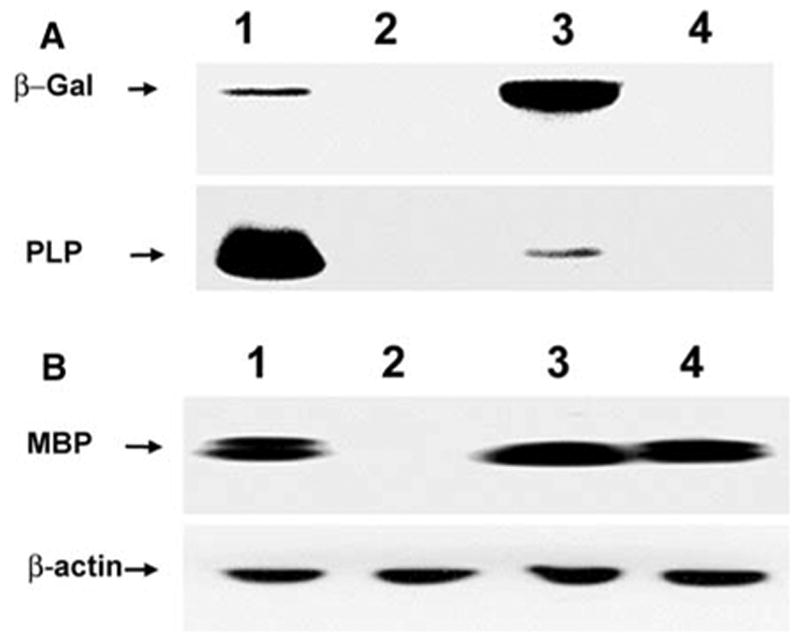

In order to further assess the reduction of transgene expression in the Plpjp background, Western blot analysis was performed with brain and spinal cord lysates. As shown in Fig. 2, the levels of PLP and β-gal were greatly reduced in the CNS of Plpjp males, compared to those present in wild-type males and Plpjp female carriers. Heterozygous Plpjp females demonstrated diminished amounts of both proteins at P7 (particularly in the spinal cord), but by P14, the levels of PLP and β-gal were comparable to those in wild-type males. Plpjp males expressed low, but detectable, amounts of β-gal protein, however PLP was not detected by Western blot analysis, presumably due to altered folding of the mutant protein and likely aggregation and/or degradation.

Fig. 2.

Western blot analysis of β-gal and PLP expression in the developing brain and spinal cord of PLP(+)Z transgenic mice. Proteins were isolated from wild-type (lanes 1–3) and Plpjp (lanes 4–6) males and heterozygous Plpjp females (lanes 7–9) at P7 (lanes 1, 4, 7), P14 (lanes 2, 5, 8), and P21 (lanes 3, 6, 9) of age. Twenty micrograms of total protein was loaded per lane. Blots were incubated with anti-PLP-specific M2 (1:2000) or anti-β-gal (1:1,000) antibodies

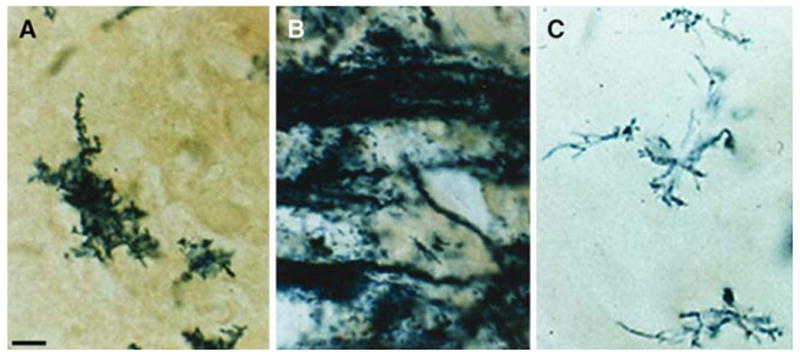

To better examine the morphology of cells expressing the transgene at high magnification, brain sections were stained with the β-gal substrate, Bluogal. Bluogal stained cells (oligodendrocytes) in the wild-type background had a stellate appearance at P5 (Fig. 3A) and exhibited large β-gal-expressing tracts, with little staining in cell bodies by P12 (Fig. 3B). Yet even at P21, β-gal expressing cells in the Plpjp male were morphologically similar to immature oligodendrocytes present in wild-type littermates at P5, staining pre-dominantly the multiple short processes of mutant cells, with little staining in cell bodies (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Bluo-gal staining for β-gal activity in brains of PLP(+)Z transgenic mice. Cortical tissue was examined from male wild-type mice at P5 (A) and P12 (B) and a Plpjp mouse at P21 (C). Bar: 10 μm

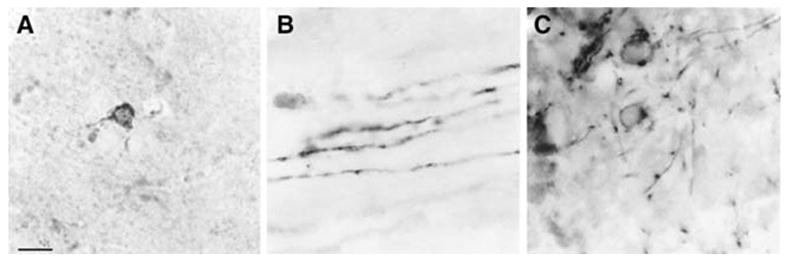

Immunocytochemical analysis confirmed a decrease in PLP(+)Z expression in the Plpjp background. When compared to age-matched wild-type males, P21 Plpjp males exhibited a dramatic decrease in both PLP and β-gal immunoreactivity in all regions examined, and MBP and CNP immunostaining was also decreased in affected males, although not as severely as for PLP and β-gal (data not shown). As seen at high magnification, the little PLP remaining was localized almost exclusively in the cell body of Plpjp oligodendrocytes (Fig. 4A), whereas in mature wild-type oligodendrocytes, localization of PLP to the cell body was rarely seen (data not shown). In sharp contrast, the β-gal transgene product in Plpjp mice was found in short oligodendrocyte processes and fibers, and only occasionally in cell bodies (Fig. 4B). CNP staining was observed in both the cell body and short fibers of Plpjp oligodendrocytes (Fig. 4C). Even though less CNP was expressed in oligodendrocytes from the Plpjp mutant, the distribution of CNP within the cell was similar to that in wild-type animals (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Distribution of PLP (A), β-gal (B) and CNP (C) in cells from the brain of a Plpjp/PLP(+)Z transgenic male, at P21. Bar: 10 μm

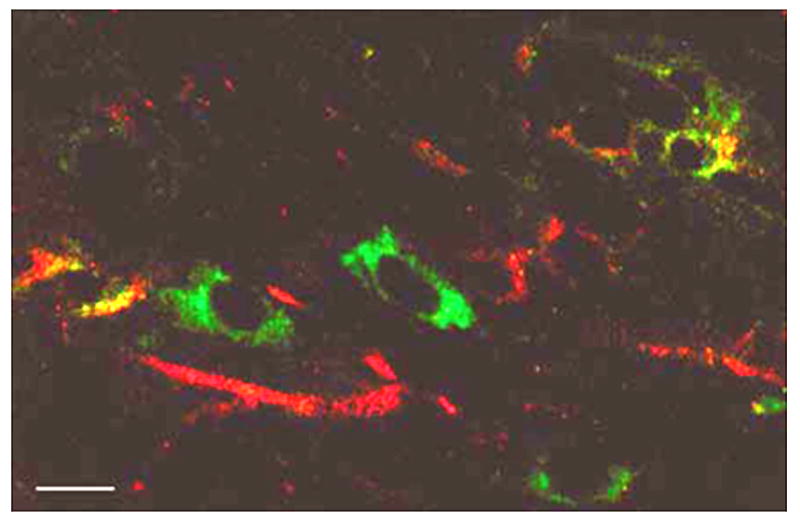

Double labeling for PLP and β-gal in Plpjp oligodendrocytes demonstrated significant partitioning of the proteins (Fig. 5). The PLP protein appeared to be restricted to the Plpjp oligodendrocyte cell body, while β-gal was detected predominantly along the processes and short fibers, with occasional cells having stain in the cell body. As seen in other studies [9, 10], it is likely that the mutant PLP protein is accumulating in the cell body. In contrast, the β-gal fusion protein, which contains the first 13 amino acids of PLP at its N-terminus and is targeted to compact myelin in wild-type mice [12], does not remain in the cell body and gets properly trafficked to the plasma membrane.

Fig. 5.

Confocal image of immunofluorescent colocalization of PLP (Fluorescein) and β-gal (Texas Red) in cells from the brain of a Plpjp male, PLP(+)Z transgenic mouse, at P21. Bar: 3.5 μm

PLP(+)Z transgene expression in the PNS in Plpjp mice

Transgene expression was also investigated in the PNS of Plpjp and wild-type males. As shown in Fig. 6, the amounts of both PLP and β-gal in sciatic nerve were decreased in Plpjp sciatic nerve, similar to that in brain. However unlike the CNS, the Plpjp mutation did not display pleiotropic effects in the PNS, as evidenced by equivalent amounts of MBP in sciatic nerve from Plpjp and wild-type males (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Western blot analysis of proteins in brain and sciatic nerve from PLP(+)Z transgenic mice at P21 of age. A: Proteins isolated from brain (lanes 1, 2) or sciatic nerve (lanes 3, 4) of wild-type (lanes 1, 3) and Plpjp (lanes 2, 4) males were analyzed for levels of β-gal and PLP. Significantly different amounts of protein from brain (7 μg) and sciatic nerve (100 μg) were loaded for analysis on the same blot. The blot was analyzed first for PLP using the M2 anti-PLP-specific antibody (1:500), then stripped and incubated with an antibody against β-gal (1:1,000). [The apparent increase in β-gal expression in normal sciatic nerve relative to normal brain simply reflects the significant increase in the amount of protein analyzed.] B: Proteins (30 μg) isolated from brain (lanes 1, 2) or sciatic nerve (lanes 3, 4) of wild-type (lanes 1, 3) and Plpjp (lanes 2, 4) males were analyzed for MBP and β-actin. The blot was analyzed first for MBP using an anti-MBP antibody (1:500), then stripped and incubated with an anti-β- actin (1:250) primary antibody

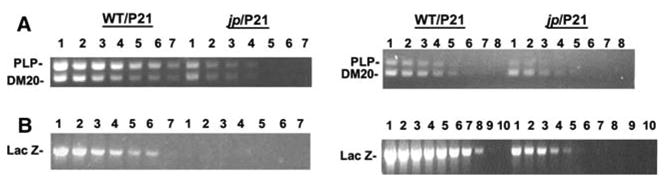

Plp/Dm20 and lacZ mRNA levels in the CNS and PNS were also analyzed semi-quantitatively by RT-PCR, which permits analysis of both Plp and Dm20 mRNAs (Fig. 7). In brain, the amounts of Plp/Dm20 mRNA were higher than lacZ in both wild-type and Plpjp males. Interestingly, lacZ mRNA levels in sciatic nerve were higher than either Plp or Dm20 mRNA in both wild-type and Plpjp males at P21. This may partially reflect the presence of two pools of alternative splice products (Plp/Dm20), while there is only one for PLP(+)Z transgene mRNA, although this does not impact their absolute expression in brain. Brain Plp mRNA levels were approximately 20-fold less in Plpjp compared to wild-type males, e.g., comparable amounts of Plp-specific RT-PCR products were generated using cDNA reaction mixture inputs of 50 ng for wild-type and 1 μg for Plpjp (Fig. 7). The amount of lacZ mRNA in Plpjp brain was decreased to an even greater extent. By contrast, in sciatic nerve, Plp/Dm20 mRNA levels were decreased less than 4-fold in Plpjp mice compared to wild-type (with Dm20 mRNA as the major constituent), while PLP(+)Z transgene expression decreased approximately 20-fold.

Fig. 7.

Relative levels of Plp/Dm20 and lacZ mRNA in PLP( + )Z transgenic mice by RT-PCR analysis. RNA isolated from whole brain or sciatic nerve of wild-type and Plpjp males at P21 was used for first strand cDNA synthesis. PCR reactions were performed with varying amounts of the cDNA mixture and primer pairs for Plp/Dm20, lacZ and α-tubulin (data not shown). A: RT-PCR results with whole brain from wild-type and Plpjp males. PCR reactions were performed with cDNA mixture inputs of 1 μg (lane 1), 500 ng (lane 2), 250 ng (lane 3), 100 ng (lane 4), 50 ng (lane 5), 25 ng (lane 6) and 12.5 ng (lane 7). B: RT-PCR results with sciatic nerve from wild-type and Plpjp males. PCR reactions were performed with cDNA mixture inputs of 4 μg (lane 1), 3 μg (lane 2), 2 μg (lane 3), 1 μg (lane 4), 500 ng (lane 5), 250 ng (lane 6), 100 ng (lane 7), 50 ng (lane 8), 25 ng (lane 9) and 12.5 ng (lane 10)

Discussion

Downregulation of the Plp gene and the PLP(+)Z transgene in oligodendrocytes

The current studies demonstrate that Plp genomic sequences contained within PLP(+)Z, which regulate expression of the PLP(+)Z transgene comparably to the endogenous Plp gene, downregulate expression of the Plp gene in both the CNS and the PNS in Plpjp mice, relative to wild-type mice. This is to be expected in the CNS. Plpjp mice, which express a mutant form of PLP due to a point mutation in the acceptor splice site of exon 5, have significant alterations in the oligodendrocyte cell cycle, where a high mitotic rate is observed accompanied by significant cell death [29–32]. Campagnoni’s group showed two decades ago that PLP protein and mRNA are dramatically downregulated in Plpjp mice [33–35]. Additionally, it has been known for some time that both Plp and Mbp transcriptional activity is decreased in the brains of affected males [5, 36]. While the obvious assumption has been that the mutant PLP protein is responsible for this change, it is possible that the point mutation itself could have had a cis effect on Plp gene activity. The current studies conclusively disprove this, since expression of the PLP(+)Z transgene, which does not contain the Plpjp point mutation, is likewise decreased in the Plpjp CNS relative to wild-type. Perhaps the reduction in transgene expression simply reflects the fact that Plpjp oligodendrocytes are compromised, triggering higher levels of cell death, and thus reducing their overall number in affected animals. However, significant numbers of GC+ oligodendrocytes are present in these animals [35, 37], and transcription of glycerol phosphate dehydrogenase, an early marker of oligodendrocyte differentiation, is unaffected [5]. In contrast, genes such as Plp, Mbp, and Mog (myelin/oligodendrocyte glycoprotein), whose expression is upregulated late in the oligodendrocyte differentiation program, are expressed at lower levels in the Plpjp CNS [5, 36, 38], much like the PLP(+)Z transgene. Thus it appears that it is the ability of the cells to fully differentiate, and hence express high levels of gene products found in mature oligodendrocytes that is compromised in the Plpjp mutant. This concept is consistent with the observation that Plpjp oligodendrocytes expressing the PLP(+)Z transgene were morphologically immature (Fig. 3). Previous studies [5] have shown that Plp gene transcription, in brain, is reduced in affected mice, with Plpjp mice at P25 having similar levels of Plp transcription as wild-type mice at P7. Other studies [38] have shown that the pattern of myelin gene expression in Plpjp oligodendrocytes is consistent with that found in immature wild-type cells. Thus, consistent with much data in the literature, expression of the PLP(+)Z transgene is reduced in the Plpjp CNS due to the immature status of oligodendrocytes in these animals.

Downregulation of the Plp gene and the PLP(+)Z transgene in Schwann cells

Few studies have assessed Plp gene regulation in the PNS. In contrast to the CNS, the Plpjp mutation in the PNS does not cause abnormal Schwann cell development or dysmyelination [39, 40]. However, expression of the PLP(+)Z transgene in the PNS, as well as the endogenous Plp gene, were decreased in Plpjp sciatic nerve relative to wild-type, while MBP levels were unaffected (Fig. 6). Since there are no overt pleiotropic effects of the Plpjp mutation in the PNS, the decreased levels of β-gal and PLP in the Plpjp PNS must be due to (Plp) regulatory sequences common to both the transgene and the endogenous gene, or to the shared nucleotide or amino acid sequence (13 N-terminal residues of PLP) between the mRNAs and proteins they encode. On the other hand, the mutated Plpjp PLP protein could conceivably participate in a negative feedback loop, decreasing its own expression, as well as that of the transgene. Since the PLP/DM20 C-terminus portion is out of frame in the mutant, it is possible that a nuclear localization signal (NLS) might have inadvertently been created. However, neither Plpjp PLP nor wild-type PLP contains an NLS when analyzed with a program that searches for NLS (http://cubic.bioc.columbia.edu/predictNLS) [41, 42]. Furthermore Anderson et al. [40] demonstrated that expression of the Plpjp PLP protein in Schwann cells did not prevent expression of wild type PLP protein. Thus, the decrease in the transcriptional activity of both the transgene and the endogenous Plp gene in Schwann cells is unlikely to be directly regulated by the mutated protein.

It is striking that there was a more precipitous drop in transgene mRNA than Plp/Dm20 mRNA gene in Plpjp mice, relative to wild-type. This was true in both the CNS and PNS, and may result from greater stability of Plp/Dm20 transcripts than transgene mRNA. Previous studies indicate that the Plp-specific sequence, which is absent from Dm20 mRNA, and the 3′-untranslated region of the Plp/Dm20 mRNA are important for stability of Plp gene transcripts in glial cells [15, 43, 44]. Since neither of these sequences is present in the transgene mRNA, amounts of the PLP(+)Z transcript are a true reflection of the transcriptional activity. Thus, the greater loss of transgene mRNA than Plp/Dm20 mRNAs in both the CNS and PNS in Plpjp mice relative to wild type is probably due, entirely, to a decrease in PLP(+)Z transcription initiation.

The downregulation of Plp/Dm20 mRNAs was less in Schwann cells than in oligodendrocytes. The stabilization elements that have been identified in the Plp mRNA particularly stabilize this mRNA in myelinating Schwann cells [43]. Thus, it is possible that since there is no loss of myelin in Plpjp peripheral nerve, the stabilization signals actively maintain Plp/Dm20 mRNAs. Since, as noted above, those stabilization elements are not present in the transgene mRNA, the decrease in PLP(+)Z mRNA levels would solely reflect a decrease in transcriptional activity.

It is unclear whether the reduction in expression of the transgene and the endogenous Plp gene in Plpjp mice results from expression of mutated PLP or DM20, or both. Unfortunately the only antibody available to detect DM20 protein by Western blot analysis recognizes a C-terminal epitope, which is altered in Plpjp PLP/DM20 proteins. Thus, only the mutant PLP protein in Plpjp mice could be examined due to the existence of PLP-specific antibodies [21]. Although the amounts, if any, of mutant DM20 in Plpjp sciatic nerve could not be determined, the PCR data (Fig. 7B) demonstrate higher amounts of Dm20 mRNA than Plp mRNA in both wild-type and Plpjp sciatic nerve. Thus, it is likely that the Plpjp DM20 protein also accumulates in Schwann cells of affected mice.

Intracellular translocation of PLP and β-galactosidase in Plpjp oligodendrocytes

Interestingly, the transgene protein and other myelin proteins moved out into the processes of Plpjp oligodendrocytes, while the Plpjp PLP protein remained in the cell body (Figs. 4 and 5). PLP and DM20 proteins are processed through the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi membranes. Thus, as reported in other studies, the mutant proteins encoded by the Plpjp gene likely cannot fold correctly and are prevented from moving further through the intracellular transport pathway [9, 45]. As mentioned earlier, the PLP(+)Z transgene encodes a protein that contains the 13 N-terminal amino acids of PLP/DM20. We have shown that the transgene fusion protein is trafficked to compact CNS myelin, presumably by these PLP/DM20 N-terminal residues [12]. Therefore, retention of Plpjp PLP/DM20 in the ER is a dominant effect, likely mediated by amino acids other than those at the N-terminus, since the transgene protein containing those amino acids was able to move through the ER and Golgi and out into the processes of Plpjp oligodendrocytes. Thus the movement of PLP/DM20 into the myelin membrane appears to be controlled substantially differently from that of other membrane proteins such as the acetylcholine receptor, in which N-terminal sequences are essential for the initial formation of a protein complex that then can be sorted to the appropriate membrane [46].

In summary, results presented here suggest that expression of the PLP(+)Z transgene is an excellent prognosticator of Plp promoter activity, even in Plpjp mice. While expression of the transgene was decreased in both the CNS and PNS of Plpjp mice relative to that in wild-type littermates, the decrease in Schwann cells occurred in the absence of any overt pleiotropic effects. MBPlevels in the PNS were unaffected, unlike the CNS, where the levels dropped in Plpjp mice. Thus, expression of Plpjp PLP/DM20 protein must signal indirectly and feedback to control Plp transcriptional activity, decreasing expression of the Plpjp gene as well as the transgene in the PNS, without affecting the expression of other myelin genes. Whether a similar signaling pathway exists in the CNS is obscured by the death of mature oligodendrocytes and the failure of immature oligodendrocytes to fully mature in the Plpjp mutant, but may well also be responsible for their decreased expression in the Plpjp CNS. The mechanisms mediating the feedback downregulation remain to be determined.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NS25304, WBM) and a postdoctoral fellowship from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (CSD). The authors thank Dannette DeWeese, Leigh Hayes and Tom Phan for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Special issue dedicated to Anthony Campagnoni.

References

- 1.Woodward K, Malcolm S. Proteolipid protein gene: Pelizaeus–Merzbacher disease in humans and neurodegeneration in mice. Trends Genet. 1999;15:125–128. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01716-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yool DA, Edgar JM, Montague P, Malcolm S. The proteolipid protein gene and myelin disorders in man and animal models. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:987–992. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.6.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macklin WB, Gardinier MV, King KD, Kampf K. An AG → GG transition at a splice site in the myelin proteolipid protein gene in jimpy mice results in the removal of an exon. FEBS Lett. 1987;223:417–421. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)80331-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nave KA, Bloom FE, Milner RJ. A single nucleotide difference in the gene for myelin proteolipid protein defines the jimpy mutation in mouse. J Neurochem. 1987;49:1873–1877. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1987.tb02449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Macklin WB, Gardinier MV, Obeso ZO, King KD, Wight PA. Mutations in the myelin proteolipid protein gene alter oligodendrocyte gene expression in jimpy and jimpymsd mice. J Neurochem. 1991;56:163–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb02576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boison D, Stoffel W. Myelin-deficient rat: a point mutation in exon III (A → C, Thr75 → Pro) of the myelin proteolipid protein causes dysmyelination and oligodendrocyte death. EMBO J. 1989;8:3295–3302. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08490.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gencic S, Hudson LD. Conservative amino acid substitution in the myelin proteolipid protein of jimpymsd mice. J Neurosci. 1990;10:117–124. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-01-00117.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nadon NL, Duncan ID, Hudson LD. A point mutation in the proteolipid protein gene of the ‘shaking pup’ interrupts oligodendrocyte development. Development. 1990;110:529–537. doi: 10.1242/dev.110.2.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gow A, Southwood CM, Lazzarini RA. Disrupted proteolipid protein trafficking results in oligodendrocyte apoptosis in an animal model of Pelizaeus–Merzbacher disease. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:925–934. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.4.925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Southwood CM, Garbern J, Jiang W, Gow A. The unfolded protein response modulates disease severity in Pelizaeus–Merzbacher disease. Neuron. 2002;36:585–596. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01045-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller MJ, Haxhiu MA, Georgiadis P, Gudz TI, Kangas CD, Macklin WB. Proteolipid protein gene mutation induces altered ventilatory response to hypoxia in the myelin-deficient rat. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2265–2273. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-02265.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wight PA, Duchala CS, Readhead C, Macklin WB. A myelin proteolipid protein-lacZ fusion protein is developmentally regulated and targeted to the myelin membrane in transgenic mice. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:443–454. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.2.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fuss B, Mallon B, Phan T, Ohlemeyer C, Kirchhoff F, Nishiyama A, Macklin WB. Purification and analysis of in vivo-differentiated oligodendrocytes expressing the green fluorescent protein. Dev Biol. 2000;218:259–274. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuss B, Afshari FS, Colello RJ, Macklin WB. Normal CNSmyelination in transgenic mice overexpressingMHCclass I H-2Ld in oligodendrocytes. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2001;18:221–234. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2001.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mallon BS, Shick HE, Kidd GJ, Macklin WB. Proteolipid promoter activity distinguishes two populations of NG2-positive cells throughout neonatal cortical development. J Neurosci. 2002;22:876–885. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-03-00876.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fewou SN, Büssow H, Schaeren-Wiemers N, Vanier MT, Macklin WB, Gieselmann V, Eckhardt M. Reversal of non-hydroxy: α-hydroxy galactosylceramide ratio and unstable myelin in transgenic mice overexpressing UDP-galactose: ceramide galactosyltransferase. J Neurochem. 2005;94:469–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonzalez JM, Bergmann CC, Fuss B, Hinton DR, Kangas C, Macklin WB, Stohlman SA. Expression of a dominant negative IFN-γ receptor on mouse oligodendrocytes. Glia. 2005;51:22–34. doi: 10.1002/glia.20182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee KK, de Repentigny Y, Saulnier R, Rippstein P, Macklin WB, Kothary R. Dominant-negative β1 integrin mice have region-specific myelin defects accompanied by alterations in MAPK activity. Glia. 2006;53:836–844. doi: 10.1002/glia.20343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li S, Moore CL, Dobretsova A, Wight PA. Myelin proteolipid protein (Plp) intron 1 DNA is required to temporally regulate Plp gene expression in the brain. J Neurochem. 2002;83:193–201. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bö L, Mork S, Kong PA, Nyland H, Pardo CA, Trapp BD. Detection of MHC class II-antigens on macrophages and microglia, but not on astrocytes and endothelia in active multiple sclerosis lesions. J Neuroimmunol. 1994;51:135–146. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(94)90075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asotra K, Macklin WB. Protein kinase C activity modulates myelin gene expression in enriched oligodendrocytes. J Neurosci Res. 1993;34:571–588. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490340509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate–phenol–chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dobretsova A, Kokorina NA, Wight PA. Functional characterization of a cis-acting DNA antisilencer region that modulates myelin proteolipid protein gene expression. J Neurochem. 2000;75:1368–1376. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0751368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meng F, Zolova O, Kokorina NA, Dobretsova A, Wight PA. Characterization of an intronic enhancer that regulates myelin proteolipid protein (Plp) gene expression in oligodendrocytes. J Neurosci Res. 2005;82:346–356. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benjamins JA, Skoff RP, Beyer K. Biochemical expression of mosaicism in female mice heterozygous for the jimpy gene. J Neurochem. 1984;2:487–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1984.tb02704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benjamins JA, Studzinski DM, Skoff RP. Biochemical correlates of myelination in brain and spinal cord of mice heterozygous for the jimpy gene. J Neurochem. 1986;6:1857–1863. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1986.tb13099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benjamins JA, Studzinski DM, Skoff RP, Nedelkoska L, Carrey EA, Dyer CA. Recovery of proteolipid protein in mice heterozygous for the jimpy gene. J Neurochem. 1989;53:279–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1989.tb07325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skoff RP. Increased proliferation of oligodendrocytes in the hypomyelinated mouse mutant-jimpy. Brain Res. 1982;248:19–31. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)91143-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knapp PE, Skoff RP, Redstone DW. Oligodendroglial cell death in jimpy mice: an explanation for the myelin deficit. J Neurosci. 1986;10:2813–2822. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-10-02813.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knapp PE, Skoff RP. A defect in the cell cycle of neuroglia in the myelin deficient jimpy mouse. Brain Res. 1987;432:301–306. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(87)90055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vermeesch MK, Knapp PE, Skoff RP, Studzinski DM, Benjamins JA. Death of individual oligodendrocytes in jimpy brain precedes expression of proteolipid protein. Dev Neurosci. 1990;12:303–315. doi: 10.1159/000111859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sorg BJ, Agrawal D, Agrawal HC, Campagnoni AT. Expression of myelin proteolipid protein and basic protein in normal and dysmyelinating mutant mice. J Neurochem. 1986;46:379–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1986.tb12979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sorg BA, Smith MM, Campagnoni AT. Developmental expression of the myelin proteolipid protein and basic protein mRNAs in normal and dysmyelinating mutant mice. J Neurochem. 1987;49:1146–1154. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1987.tb10005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Verity AN, Levine MS, Campagnoni AT. Gene expression in the jimpy mutant: evidence for fewer oligodendrocytes expressing myelin protein genes and impaired translocation of myelin basic protein mRNA. Dev Neurosci. 1990;12:359–372. doi: 10.1159/000111864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shiota C, Ikenaka K, Mikoshiba K. Developmental expression of myelin protein genes in dysmyelinating mutant mice: analysis by nuclear run-off transcription assay, in situ hybridization, and immunohistochemistry. J Neurochem. 1991;56:818–826. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb01997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ghandour MS, Skoff RP. Expression of galactocerebroside in developing normal and jimpy oligodendrocytes in situ. J Neurocytol. 1988;17:485–498. doi: 10.1007/BF01189804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thomson CE, Anderson TJ, McCulloch MC, Dickinson P, Vouyiouklis DA, Griffiths IR. The early phenotype associated with the jimpy mutation of the proteolipid protein gene. J Neurocytol. 1999;28:207–221. doi: 10.1023/a:1007024022663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sidman RL, Dickie MM, Appel SH. Mutant mice (quaking and jimpy) with deficient myelination in the central nervous system. Science. 1964;144:309–310. doi: 10.1126/science.144.3616.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anderson TJ, Montague P, Nadon N, Nave K-A, Griffiths IR. Modification of Schwann cell phenotype with Plp transgenes: evidence that the PLP and DM20 isoproteins are targeted to different cellular domains. J Neurosci Res. 1997;50:13–22. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19971001)50:1<13::AID-JNR2>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cokol M, Nair R, Rost B. Finding nuclear localization signals. EMBO Rep. 2000;1:411–415. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nair R, Carter P, Rost B. NLSdb: database of nuclear localization signals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:397–399. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jiang H, Duchala CS, Awatramani R, Shumas S, Carlock L, Kamholz J, Garbern J, Scherer SS, Shy ME, Macklin WB. Proteolipid protein mRNA stability is regulated by axonal contact in the rodent peripheral nervous system. J Neurobiol. 2000;44:7–19. doi: 10.1002/1097-4695(200007)44:1<7::aid-neu2>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mallon BS, Macklin WB. Overexpression of the 3′-untranslated region of myelin proteolipid protein mRNA leads to reduced expression of endogenous proteolipid mRNA. Neurochem Res. 2002;27:1349–1360. doi: 10.1023/a:1021623700009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roussel G, Neskovic NM, Trifilieff E, Artault JC, Nussbaum JL. Arrest of proteolipid transport through the Golgi apparatus in Jimpy brain. J Neurocytol. 1987;16:195–204. doi: 10.1007/BF01795303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Verrall S, Hall ZW. The N-terminal domains of acetylcholine receptor subunits contain recognition signals for the initial steps of receptor assembly. Cell. 1992;68:23–31. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90203-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]