Abstract

Purpose

To determine whether topical ocular hypotensive medication is associated with refractive changes, visual symptoms, decreased visual function, or increased lens opacification.

Design

Multicenter clinical trial

Methods

We compared the medication and observation groups of OHTS during 6.3 years of follow-up with regard to the rate of cataract and combined cataract/filtering surgery, and change from baseline in visual function, refraction and visual symptoms. A one-time assessment of lens opacification was done using the Lens Opacities Classification System III (LOCS III) grading system.

Results

An increased rate of cataract extraction and cataract/filtering surgery was found in the medication group (7.6%) compared to the observation group (5.6%) (HR 1.56; 95% CI 1.05–2.29). The medication and observation groups did not differ with regard to changes from baseline to June 2002 in Humphrey visual field mean deviation, Humphrey visual field foveal sensitivity, Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) visual acuity, refraction and visual symptoms. For the medication and observation groups, LOCS III readings were similar for nuclear color, nuclear opalescence and cortical opacification. There was a borderline higher mean grade for posterior subcapsular opacity in the medication group (0.43 ± 0.6 SD) compared to the observation group (0.36 ± 0.6 SD) (p=0.07).

Conclusion

We noted an increased rate of cataract extraction and cataract/filtering surgery in the medication group as well as a borderline higher grade of posterior subcapsular opacification in the medication group on LOCS III readings. We found no evidence for a general effect of topical ocular hypotensive medication on lens opacification or visual function.

Introduction

For decades, clinicians have questioned whether topical ocular hypotensive medication initiates or accelerates cataract formation. An increased prevalence of lens opacities has been reported in some case-control studies of participants with glaucoma or ocular hypertension.1–5 Furthermore, a recent large, well defined population-based sample6 and a recent clinical trial7 found a higher incidence of nuclear sclerosis among participants treated with topical ocular hypotensive medications. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study (OHTS) found a higher incidence of cataract extraction among participants randomized to topical ocular hypotensive medication compared to participants in the observation group.8

To further investigate the possible role of topical ocular hypotensive medication in initiating or accelerating lens opacification in OHTS, we compared the medication and observation groups during follow-up with regard to the rate of cataract extraction and combined cataract/filtering surgery and change from baseline in visual function, refraction and visual symptoms. In addition, a one-time assessment of the lens of each eye of participants was completed by masked examiners using the Lens Opacities Classification System III (LOCS III).9

METHODS

Study Design

The OHTS is a multi-center randomized trial of the safety and efficacy of topical ocular hypotensive medication in delaying or preventing the onset of primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) in individuals with ocular hypertension. A detailed description of the study has been published previously10 and can be found online at https://vrcc.wustl.edu/mop/mop.htm. The design and methods of OHTS are briefly summarized below.

Participants signed a HIPAA compliant informed consent form approved by the institutional review board of each clinic. Eligible individuals were randomized to either observation (n=819) or treatment with topical ocular hypotensive medication (n=817). Neither the participant nor the clinician was masked as to the randomization assignment. The treatment goal was to achieve an intraocular pressure (IOP) of 24 mm Hg or less and a 20% reduction from baseline IOP but not necessarily lower than 18 mm Hg. Clinicians could prescribe one or more commercially approved topical ocular hypotensive medications to achieve the treatment goal. The mean age at baseline was 55.4 ± 9.6 SD years, 69% of the participants were self-identified as “White, not of Hispanic origin,” 25% as “Black, not of Hispanic origin,” and 3.6% as “Hispanic.” Baseline IOP was 24.9 ± 2.7 SD mm Hg (average of right and left eyes). The primary study outcome was the development of POAG as determined by reproducible visual field abnormality and/or optic disc deterioration detected by masked graders at reading centers and attributed to POAG by a masked Endpoint Committee.

From the start of enrollment in February 1994 to June 2002, participants were managed according to their randomization assignment. In June 2002, OHTS published its primary outcome paper reporting the efficacy of topical ocular hypotensive medication in reducing the incidence of POAG.8 After June 2002, medication was offered to participants originally randomized to observation. Participants originally randomized to medication continued to receive medication.

Change in Visual Function and Refraction

The medication and observation groups were compared with regard to change from baseline to June 2002 for refraction (spherical equivalent) and the following indices of visual function:

Humphrey full threshold 30-2 visual field mean deviation

Humphrey full threshold 30-2 visual field foveal sensitivity

Best corrected Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) visual acuity Humphrey 30-2 full threshold testing was completed every 6 months. Refraction and best corrected ETDRS visual acuity were completed every 12 months.

Sixteen participants who had undergone cataract extraction in one or both eyes prior to OHTS were excluded leaving 99% of the randomized participants (1,620 of 1,636) available for analyses of visual function and refraction. Among these 1,620 participants, follow-up data were excluded after events that could produce lens opacification, decreased visual function or interfere with data analysis including: 1. developing POAG, 2. undergoing cataract extraction or combined cataract/filtering surgery, 3. developing a systemic or ocular condition that severely reduced visual function e.g. central retinal vein occlusion, 4. initiating medication in an observation participant, and 5. discontinuing medication in a medication participant. Data for both eyes were censored after the occurrence of the first censoring event in either eye of a participant in analyses of visual function and refraction.

Differences between randomization groups in the rate of change from baseline to June 2002 or to the first censoring date were estimated using data for each eye of each participant using multivariate regression models implemented with Proc Mixed, SAS® statistical software version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). We report the coefficient of change per year by randomization group. These models adjusted for the correlation between the two eyes of each participant and included as covariates age, race, diabetes, corticosteroid use and the use of topical ocular hypotensive medication prior to OHTS. Multivariate models of mean deviation did not include age as a covariate because mean deviation is adjusted for age in STATPAC 2. Because smoking history was recorded late in the study and was available for a smaller sample (n=1,387 of 1,620), we performed the primary multivariate analyses without history of smoking and repeated the analyses with smoking history. Smoking history was positive if the participant responded “yes” to the question “Have you ever smoked 100 or more cigarettes to date?”

To improve detection of changes in small subgroups, we also compared the medication and observation groups with regard to the occurrence of two threshold events indicative of decreased visual function- the occurrence of ETDRS visual acuity ≤ 39 letters (approximately 20/40 Snellen equivalent) in either eye or the occurrence of a visual field test with mean deviation p < 0.05 in either eye. Cox proportional hazards models were used to determine if the cumulative probability of these events differed between the two randomization groups. Covariates in the Cox models included age, race, diabetes, corticosteroid use and use of topical ocular hypotensive medication prior to OHTS. Multivariate models were rerun with the same covariates and history of smoking.

Change in Glaucoma Symptom Checklist

OHTS started administration of the Glaucoma Symptom Checklist in November 1996. The Glaucoma Symptom Checklist, which was completed every 6 months by participants, includes 4 visual symptoms - “blurry or dim vision,” “halos around lights,” “hard to see in daylight,” “hard to see in darkness.” Participants ranked how bothered they were by these symptoms on a scale from “1=not at all, unaware of any problems” to “4 = a lot, cannot work or cannot do usual activities.” Data from 2 or more visits prior to June 2002 were available for 93% (759 of 810) of the observation participants and 91% (738 of 810) of the medication participants.

Multivariate models (PROC MIXED) as described above were used to compare randomization groups with regard to change in visual symptoms from baseline to June 2002 or to the first censoring event. Since the 4 visual symptoms were highly intercorrelated, we analyzed the mean of the 4 visual symptom scores for each visit. Multivariate models were repeated with the same covariates and history of smoking.

National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire (NEI-VFQ)

OHTS started annual administration of the NEI-VFQ in March 2001. Data from one NEI-VFQ questionnaire were available for 35% (287 of 810) of the observation participants and 42% (338 of 810) of the medication participants by June 2002 or prior to a censoring event. While the number of NEI-VFQ questionnaires available for this analysis differed between randomization groups (p=0.01); no demographic or baseline clinical characteristics were found that differentiated participants with and without data from the NEI-VFQ questionnaire.

Each of the vision specific subscales - color vision, distance activities, dependency, driving, general vision, mental health, near activities, ocular pain, peripheral vision, role difficulties and social functioning- was analyzed separately with no correction for multiple comparisons. A composite score consisting of the overall mean of the subscale scores was also analyzed. Randomization groups were compared using analysis of variance with covariates of age, race, diabetes, corticosteroid use and the use of topical ocular hypotensive medication prior to OHTS. The multivariate models were repeated with the addition of history of smoking.

Cataract Extraction and Combined Cataract/Filtering Surgery

Ocular history was updated at every 6 month follow-up visit. The time from baseline to the first report of either cataract extraction or combined cataract/filtering surgery was calculated using data from all participants with no censoring except for death or loss to follow-up for 1,620 participants (810 observation participants and 810 medication participants). Sixteen participants had cataract extraction in one or both eyes prior to OHTS and were not included in this analysis. Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate the hazard ratio associated with randomization group. Baseline factors found to be associated with cataract extraction in univariate analyses included race, baseline IOP, baseline mean deviation, baseline visual acuity worse than 20/20, and use of calcium channel blockers at baseline. These factors were included in the multivariate Cox proportional hazards models in addition to those factors described previously (age, diabetes, corticosteroid use and use of topical ocular hypotensive medication prior to OHTS). The multivariate models were repeated with the addition of history of smoking.

Lens Opacity Classification System III (LOCS III)

All LOCS III graders completed training under the direction of Leo T. Chylack, Jr., M.D. After dilation of a participant’s pupils, the grader assigned a numeric grade to the degree of nuclear opalescence (0.1 to 6.9), nuclear color (0.1 to 6.9), cortical opacity (0.1 to 5.9) and posterior subcapsular opacity (0.1–5.9). Photographic standards were provided for each integer value on the scale e.g. 1.0, 2.0. The grader interpolated decimal values between these photographic standards so the available scale range for nuclear color was 70 units from 0.1 to 6.9 in 0.1 increments. Graders were masked as to randomization, POAG status, visual acuity and Humphrey visual field test results.

LOCS III gradings were begun in March 2003 after treatment had already been offered to participants in the observation group. LOCS III measurements were discontinued October 31, 2004 at the recommendation of the OHTS Data and Safety Monitoring Committee (DSMC). By the time of the LOCS III grading, participants originally randomized to observation had received ocular hypotensive medication for a median of 1.2 years (range 0.0 to 8.6 years) and participants originally randomized to medication had been on ocular hypotensive medication for a median of 8.5 years (range 0.0 to 10.2 years). Eyes that had developed POAG or had severely compromised vision due to ocular or systemic co-morbidities were included in all analyses of LOCS III data. We excluded eyes that had undergone cataract extraction or combined cataract/filtering surgery. The unoperated fellow eyes were used when available to minimize missing data. Masked LOCS III gradings were available for 78% (1,017 of 1,300) of the participants who signed an informed consent form to continue follow-up in OHTS after June 2002. An equal percentage of medication participants (78% or 511 of 654) and observation participants (78% or 506 of 646) had LOCS III gradings.

Multivariate models, which included data from both eyes (or one eye if both eyes were not available) and adjusted for the correlation between a participant’s two eyes, were implemented with Proc Mixed, SAS® statistical software version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC). Analyses were also run with the eye having the worse LOCS III grade or a random eye when both eyes had identical grades. Multivariate models for LOCS III data included as covariates the use of topical ocular hypotensive medication in OHTS, age, race, diabetes mellitus, corticosteroid use and the use of topical ocular hypotensive medication prior to OHTS. Multivariate models were repeated with the addition of history of smoking as a covariate.

Results

Change in Visual Function or Refraction

Data for analyses of visual function and refraction from baseline to June 2002 or a censoring date were available for 99% (1,620 of 1,636) of the randomized participants. Table 1 reports duration of follow-up available for 337 participants with censoring of follow-up data and for 1,283 participants with no censoring (mean follow-up 6.3 years). Duration of follow-up prior to the censoring event was sufficient to estimate slope coefficients for these 337 participants, and thus they could be included in the primary analyses.

Table 1.

Amount of Data (years) Available for Analyses of Change in Visual Function, Refraction and Visual Symptoms for Participants with Data Included to June 2002 and for Participants with Data Excluded Following a Censoring Event Prior to June 2002.

| Participants N | % | Amount of Data (Years) Available for Analyses Mean ± SD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants Not censored | 1283 | 79.2 | 6.3 | 1.7 |

| Participants Censored after an event | ||||

| Developed POAG | 129 | 8.0 | 4.1 | 1.8 |

| Cataract extraction or combined cataract/filtering surgery | 109 | 6.7 | 4.8 | 1.8 |

| Visual function severely reduced due to comorbidity | 7 | 0.4 | 5.0 | 2.7 |

| Observation participant starts ocular hypotensive medication | 45 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 1.8 |

| Medication participant off ocular hypotensive medication | 47 | 2.9 | 2.5 | 1.6 |

| Total | 1,620 | 100 | 5.8 | 2.0 |

No difference between randomization groups was detected in the coefficient of change per year in Humphrey full threshold foveal sensitivity, Humphrey full threshold mean deviation, best-corrected ETDRS visual acuity and refractive correction (spherical equivalent). Table 2 reports the mean of right and left eyes at baseline and at the last follow-up visit and the coefficient of change per year for visual function indices and refractive correction.

Table 2.

Comparison of the Observation Group and the Medication Group at Baseline, Last Visit and Coefficient of Change for Visual Function and Refraction (Spherical Equivalent).

| Group | n | Baseline* Mean ± SD | Last visit** Mean ± SD | Coefficient of change per year*** | P value+ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foveal Sensitivity (dB) |

Observation

Medication |

810

810 |

36.0 ± 1.5

36.0 ± 1.5 |

34.6 ± 2.5

34.7 ± 2.1 |

−0.21

−0.22 |

0.53 |

| Mean Deviation (dB) |

Observation

Medication |

810

810 |

0.21 ± 1.03

0.28 ± 1.07 |

−0.42 ± 1.94

−0.20 ± 1.57 |

−0.073

−0.061 |

0.32 |

| ETDRS (Letters correct) |

Observation

Medication |

807

798 |

55.7 ± 6.9

55.5 ± 7.4 |

53.0 ± 7.0

52.7 ± 6.9 |

−0.55

−0.56 |

0.89 |

| Spherical Equivalent (Diopters) | Observation | 810 | −0.60 ± 2.4 | −0.48 ± 2.3 | 0.021 | 0.82 |

| Medication | 810 | −0.67 ± 2.3 | −0.53 ± 2.4 | 0.022 |

Mean of right and left eyes of each participant at baseline

Mean of right and left eyes of each participant at the last visit before June 2002 or last visit prior to censoring

Change per year is expressed in units of measurement of the variable

Multivariate models utilized all data from baseline to last follow-up or censoring date of each eye and adjusted for age, race, use of topical medication prior to OHTS, diabetes mellitus, and use of corticosteroids. Models with these same covariates and the history of smoking yielded nearly identical results. Models for mean deviation did not include age as a covariate.

Forty-five percent (621 of 1387) of the participants reported a history of smoking as defined in OHTS, 47% (323 of 695) in the medication group and 43% (298 of 692) in the observation group). Nearly identical results were found when the multivariate models were rerun adding history of smoking to the covariates listed in the table. (Data not presented.)

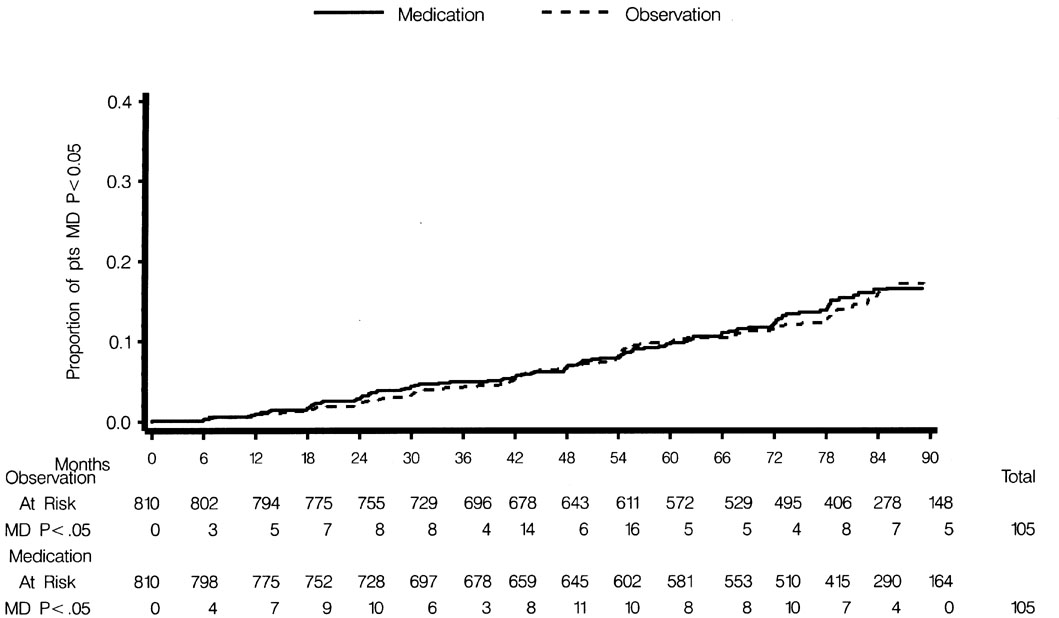

No difference was detected in the cumulative probability of an ETDRS visual acuity ≤ 39 letters (approximately equivalent to Snellen 20/40) in one or both eyes between the observation group (17%, 134 of 807) and the medication group (16%, 125 of 800) (HR 0.95; 95% CI 0.74–1.21) (Figure 1). No difference was detected in the cumulative probability of a Humphrey visual field test with mean deviation p<0.05 in one or both eyes between the observation group (13%, 105 of 810) and the medication group (13%, 105 of 810) (HR 0.99; 95% CI 0.76–1.30) (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Comparison of the Observation Group and the Medication Group in the cumulative proportion of participants with ≤ 39 letters correct on ETDRS visual acuity (approximately 20/40 Snellen equivalent) before June 2002 or a censoring event.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the Observation Group and the Medication Group in the cumulative probability of participants with Humphrey mean deviation (p <0.05) on any field prior to June 2002 or a censoring event.

Change in Glaucoma Symptom Checklist

No difference between randomization groups was detected in the coefficient of change in the mean of the four visual symptom question scores of the Glaucoma Symptom Checklist from 1996 to June 2002 or a censoring date. The coefficient of change per year was 0.024 points per year in the observation group (n=759) and 0.020 points per year in the medication group (n=738) on a scale from “1=not at all, unaware of any problems” to “4 = a lot, cannot work or cannot do usual activities” (P=0.44).

National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire

One completed NEI-VFQ questionnaire was available for analysis for 287 observation participants and 338 medication participants. No differences between randomization groups were detected on any of the 11 subscales or the composite score (p=0.21 to 0.98 in multivariate models). No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons.

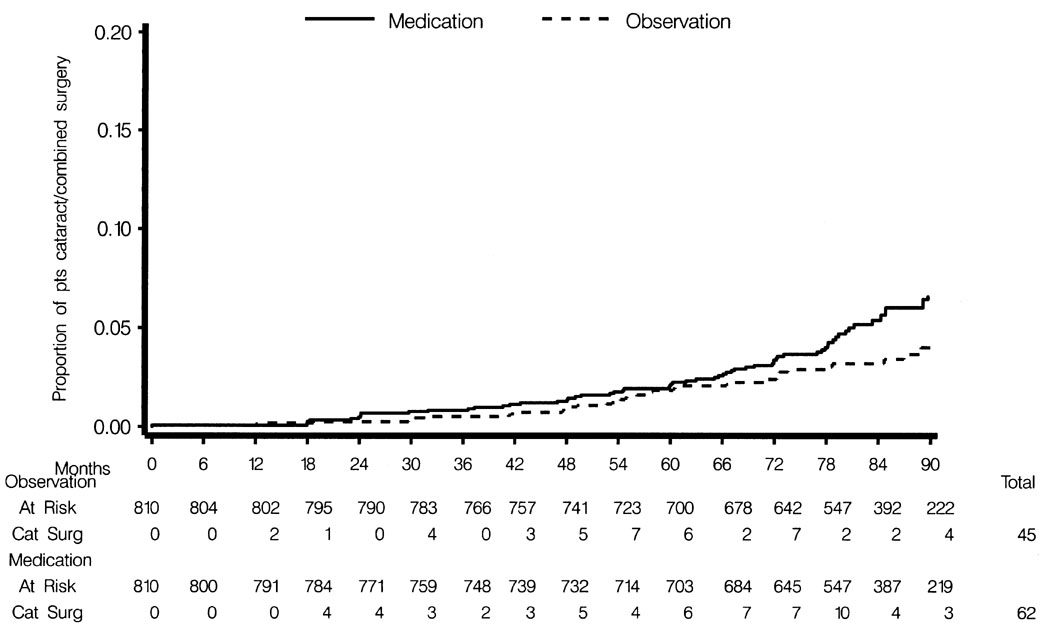

Cataract Extraction or Combined Cataract/Filtering Surgery from Baseline to June 2002

The percent of participants undergoing cataract extraction or combined cataract/filtering surgery from baseline to June 2002 was significantly higher in the medication group (7.6%, 62 of 810) compared to the observation group (5.6%, 45 of 810); HR 1.56; 95% CI 1.05–2.29) (Fig. 3). In the medication group, 5 of the 62 surgeries were combined procedures, and in the observation group, 2 of the 45 surgeries were combined procedures. No participant had filtering surgery prior to cataract extraction or combined procedure. Other factors significantly associated with higher risk for cataract extraction or combined procedure in the multivariate model included older age (HR for each decade, 2.28; 95% CI 1.81–2.87), self-identified white race (HR 1.72; 95% CI 1.00–2.96), and baseline visual acuity worse than 20/20 (HR 2.86; 95% CI 1.88–4.34). Cox proportional hazards model with smoking yielded nearly identical results (HR for randomization group 1.52; 95% CI 1.01–2.28).

Figure 3.

Comparison of the Observation Group and the Medication Group in the cumulative probability of participants having cataract extraction or combined cataract/filtering surgery from baseline to June 2002.

We conducted exploratory data analyses to determine why the rate of surgery was higher in the medication group. We investigated the possible influence of the following factors: 1. clinic to clinic variability in the rate of cataract and combined cataract/filtering surgery; 2. changes in visual function or refraction prior to surgery; 3. higher baseline IOP; and 4. higher follow-up IOP prior to surgery. Clinics varied considerably in their rate of cataract extraction and combined cataract/filtering procedures (range of 2% to 17% of participants at the clinics) prior to June 2002. To rule out the possibility that a few clinics accounted for the overall difference between randomization groups, we reran the Cox proportional hazards models excluding the 2 clinics with the highest cataract extraction rates. We still found a higher cumulative probability of cataract and combined cataract/filtering surgery in the medication group.

To determine if the clinical threshold for performing cataract extraction and combined cataract/filtering surgery was different between randomization groups, we compared the rate of change in visual function up to the time of cataract extraction in the observation and medication participants. Excluded from this subgroup analysis were 7 of 62 medication participants and 7 of 45 observation participants who had a censoring event prior to cataract extraction. No differences by randomization group were detected among those who underwent cataract extraction or combined procedures (Table 3) in the coefficient of change for refraction (p=0.27), Humphrey visual field mean deviation (p=0.56), Humphrey visual field foveal sensitivity (p=0.35), or best-corrected ETDRS visual acuity (p=0.88).

Table 3.

Comparison of Participants in the Observation Group and the Medication Group who undergo Cataract Extraction or Cataract/Filtering Surgery at Baseline, Last Visit and Coefficient of Change for Visual Function and Refraction (Spherical Equivalent).

| Participants undergoing cataract or combined procedures | N* | Baseline Mean ± SD | Last Follow-up Visit prior to Surgery Mean ± SD | Coefficient of change per year** | P Value *** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foveal Sensitivity (dB) |

Observation

Medication |

38

55 |

35.09 ± 1.65

34.90 ± 1.95 |

33.8 ± 2.4

33.8 ± 2.3 |

−0.38

−0.31 |

0.35 |

| Mean Deviation (dB) |

Observation

Medication |

38

55 |

0.02 ± 1.14

0.16 ± 1.09 |

−0.95 ± 2.02

−0.91 ± 1.71 |

−0.28

−0.23 |

0.56 |

| ETDRS (letters correct) |

Observation

Medication |

38

55 |

52.24 ± 5.44

51.30 ± 8.37 |

46.6 ± 8.5

48.3 ± 7.6 |

−1.18

−1.24 |

0.88 |

| Spherical Equivalent (Diopters) | Observation | 38 | −0.46 + 1.88 | −0.77 ± 1.5 | −0.12 | 0.27 |

| Medication | 55 | −0.23 ± 2.41 | −0.48 ± 1.9 | −0.07 |

7 of 62 medication participants and 7 of 45 observation participants are excluded due to a censoring event prior to cataract extraction or combined cataract/filtering procedure. See Table 1 for details.

Change per year is expressed in units of measurement of the variable

Multivariate models utilized all data from baseline to the visit prior to surgery of the first eye to undergo surgery, multivariate models adjusted for age, race, use of topical medication prior to OHTS, diabetes mellitus and use of corticosteroids.

To determine if high IOP influenced the decision to proceed with cataract extraction or combined cataract/filtering surgery, we compared the baseline and follow-up IOP up to the time of surgery for participants who subsequently underwent cataract or combined surgery to those who did not. In the observation group, no difference in mean baseline IOP was detected between participants who did undergo or subsequently did not undergo cataract or combined procedures (24.9 mm Hg ± 2.8 SD versus 24.5 mm Hg ± 2.6 SD respectively; p=0.40). Among observation participants who subsequently underwent surgery, mean follow-up IOP prior to surgery was slightly lower (23.0 ± 2.5 SD) compared to observation participants who did not undergo surgery (23.9 ± 3.0 SD, p =0.05).

In the medication group, participants who underwent cataract extraction or combined procedures had a higher mean baseline IOP compared to those who did not (25.9 mm Hg ± 2.6 SD and 24.7 mm Hg ± 2.7 SD respectively, p =0.004). Among medication participants who subsequently underwent surgery, mean follow-up IOP prior to surgery was 19.4 ± 1.9 SD compared to 19.2 + 2.2 SD among medication participants who did not undergo surgery (p =0.43). We also investigated if medication participants who missed the IOP goal more frequently were more likely to undergo cataract extraction or combined cataract/filtering surgery. No difference was detected in the percent of visits in which both eyes met the IOP target between medication participants who underwent cataract extraction or combined cataract/filtering surgery (68.5% ± 25.3 SD) versus the medication participants who did not undergo surgery (67.7% ± 28.4 SD; p=0.85).

Lens Opacities Classification System III (LOCS III)

Masked LOCS III gradings, which were initiated March 2003 and discontinued October 31, 2004 at the recommendation of the DSMC, were completed for 78% of the medication participants (511 of 654) and 78% of the observation participants (506 of 646). In a subset of 181 participants, a second LOCS III grading was performed by the same masked grader before the discontinuation date. In this subset, we examined the test-retest agreement between the first and second LOCS III gradings using a Pearson correlation coefficient. The average interval between the first and second LOCS III gradings was 10.3 months ± 2.7 SD. Pearson correlation coefficients between the first and second gradings were 0.76 for nuclear color, 0.67 for nuclear opalescence, 0.70 for cortical opacity and 0.51 for posterior subcapsular opacity.

Tables 4 and 5 report the mean LOCS III gradings for the average of both eyes of each participant as well as for the “worse eye” of each participant by randomization group. In multivariate models, the effect of duration of exposure to medication was better captured by randomization group than by months on topical ocular hypotensive medication because the distribution of duration on medication was bimodal. (Median treatment period was 1.2 years in the observation group versus 8.5 years in the medication group.) Therefore, multivariate analyses of LOCS III used randomization group to classify medication exposure time.

Table 4.

LOCS III Grading by Randomization Group: Mean of Right and Left Eyes of each Participant

| Observation (Mean ± SD) N = 506 | Medication (Mean ± SD) N = 511 | P- Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median Duration of Medication (yrs) | 1.2 | 8.5 | |

| Nuclear Color (scale 0.1–6.9) | 2.50 ± 1.3 | 2.54 ± 1.4 | 0.61 |

| Nuclear Opalescence (scale 0.1–6.9) | 2.27 ± 1.1 | 2.31 ± 1.1 | 0.50 |

| Cortical Opacity (scale 0.1–5.9) | 1.05 ± 1.1 | 1.07 ± 1.1 | 0.73 |

| Posterior Subcapsular Opacity (scale 0.1–5.9) | 0.36 ± 0.6 | 0.43 ± 0.6 | 0.067 |

(Multivariate models utilized one LOCS III grading for each eye adjusting for the correlation between the eyes of the participant. The multivariate model adjusted for age, race, use of topical medication prior to OHTS, diabetes mellitus, and use of steroids. Models with these same covariates and history of smoking yielded nearly identical results.

Table 5.

LOCS III Grading by Randomization Group: Worse Eye

| Observation (Mean ± SD) N = 506 | Medication (Mean ± SD) N = 511 | P- Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median Duration of Medication (yrs) | 1.2 | 8.5 | |

| Nuclear Color (scale 0.1–6.9) | 2.66 ± 1.4 | 2.69 ± 1.4 | 0.66 |

| Nuclear Opalescence (scale 0.1–6.9) | 2.42 ± 1.1 | 2.46 ± 1.2 | 0.51 |

| Cortical Opacity (scale 0.1–5.9) | 1.23 ± 1.2 | 1.27 ± 1.3 | 0.61 |

| Posterior Subcapsular Opacity (scale 0.1–5.9) | 0.45 ± 0.7 | 0.54 ± 0.8 | 0.054 |

Multivariate model utilized one LOCS III grading per participant and adjusted for age, race, use of topical medication prior to OHTS, diabetes mellitus, and use of steroids. Models with these same covariates and history of smoking yielded nearly identical results.

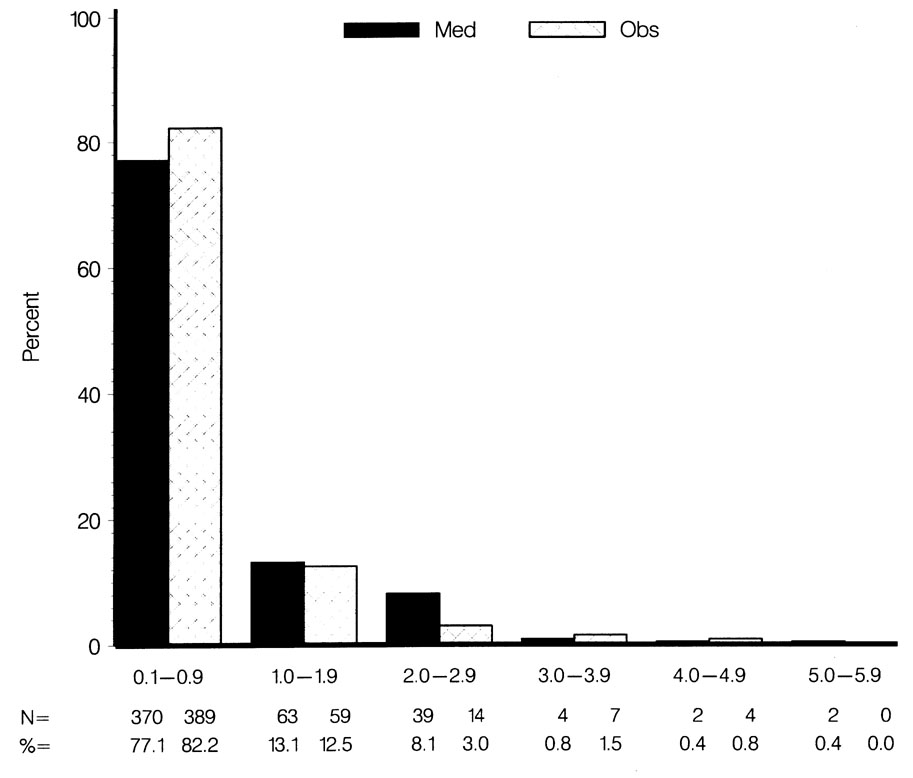

No statistically significant or clinically significant differences between randomization groups were detected for nuclear opalescence, nuclear color or cortical opacity in multivariate models that included data from “both eyes” or data from the “worse eye” of each participant (Tables 4 and 5). Covariates in the multivariate models included randomization group, age, race, diabetes mellitus, corticosteroid use and the use of topical ocular hypotensive medication prior to OHTS. A trend for higher mean posterior subcapsular opacity grades was detected in the medication group compared to the observation group in univariate as well as multivariate models for “both eyes” (0.43 ± 0.6 SD and 0.36 ± 0.6 SD respectively, p=0.067) as well as for the “worse eye” (0.54 ± 0.8 SD and 0.45 ± 0.7 SD respectively, p=0.054). A bar chart (Figure 4) shows the distribution of posterior subcapsular opacity gradings by randomization group in the worse eye.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the Observation Group and the Medication Group in the distribution of LOCS III posterior subcapsular opacity grades in the worse eye.

Multivariate models for nuclear color, nuclear opalescence, cortical and posterior subcapsular for “both eyes” and “worse eyes” were rerun with the same covariates plus history of smoking and yielded nearly identical results. (Results not presented.)

DISCUSSION

Clinicians have long wondered whether topical ocular hypotensive medication initiates or accelerates cataract formation. While it is widely accepted that the cholinesterase inhibitors cause cataract,11–13 the possibility the cataractogenic effect of direct cholinergic agonists such as pilocarpine14 could cause cataract has never been proven definitively. Some researchers have questioned whether drugs that inhibit aqueous humor formation can affect the metabolism of the lens, leading to cataract formation. Finally, other researchers have suggested that preservatives in eye drops, such as benzalkonium chloride, can cause cataract.15

A number of studies have linked glaucoma with an increased risk of cataract or cataract extraction.1–5 Some of these studies attribute much of the increased risk of cataract to the treatment, particularly topical anticholinesterase drugs and filtering surgery, rather than to the disease itself. Some epidemiologic studies associate higher levels of intraocular pressure or ocular hypertension with increased incidence or prevalence of cataract or cataract surgery,16–18 whereas in other studies the relationship was not confirmed.6

The Barbados Eye Study in a population of mostly Afro-Caribbean participants reported a threefold increased incidence of developing nuclear cataract among participants treated with topical ocular hypotensive medications, mostly beta blockers. The study also reported a borderline increase in posterior subcapsular opacification in the participants on medication.6 The Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial reported an increased incidence of LOCS II gradings ≥ 2 for nuclear opacification in patients who received topical betaxalol and laser trabeculoplasty.7

In OHTS, the rate of cataract and combined cataract/filtering surgery was higher in the medication group compared to the observation group. Sixty-two of 810 (7.6%) participants in the medication group had cataract or combined cataract/filtering surgery as opposed to 45 of 810 (5.6%) participants in the observation group. It is important to emphasize that there were no set criteria in OHTS for cataract extraction or combined procedures. The decision to perform cataract or combined cataract/filtering surgery was made by the clinician and the study participant. We attempted to determine whether there was a tendency toward earlier surgery in the medication group. The participants undergoing cataract extraction in the two randomization groups did not differ in the slope of change from baseline to the time of surgery in refraction, Humphrey visual field mean defect, Humphrey visual field foveal sensitivity, visual symptoms and ETDRS visual acuity. However, it is still possible that there was a tendency toward earlier surgery in the medication group, perhaps related to clinicians wanting to achieve low IOP levels in medication participants. We have no way to exclude this possibility.

We looked for an overall effect of medication on visual function, visual symptoms and refractive error by comparing the slope of change of EDTRS visual acuity, Humphrey visual field mean defect, Humphrey visual field foveal sensitivity, refraction and visual symptoms from baseline to June 2002 or a censoring date. We found no differences in the slopes of change between the medication and the observation groups. It is unlikely that the greater rate of cataract extraction in the medication group (62 people in the medication group versus 45 people in the observation group) would mask any overall group differences given the sample size of 1620 participants and the inclusion of all data from baseline to the date of surgery among participants undergoing surgery.

We performed LOCS III readings after participants originally randomized to observation were offered medication. Thus, the LOCS III assessments were made when the original medication group had received treatment for 8.5 years, and the original observation group had received treatment for 1.2 years. We found no difference between the groups for nuclear color, nuclear opalescence, and cortical opacity. We found a borderline difference of approximately one unit on a 60-point scale in the mean posterior subcapsular opacity grading. This trend was noted when the grading of both eyes of a participant were averaged and when the worse eye of each participant was analyzed. It should be noted that in OHTS the posterior subcapsular grading was the least reproducible of the LOCS III gradings (Pearson Correlation Coefficient .51 versus .67 to .75 for the other three types). We did not collect information on the type of cataract removed in OHTS, so we cannot comment on whether posterior subcapsular opacities contributed to the need for cataract extraction during the study.

As noted above, the Barbados Eye Study6 and the Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial7 reported an increase in nuclear opacification in treated participants. We did not find such an increase in OHTS. We cannot fully explain this difference but it may be explained in part by differences in the populations studied, treatment regimens, and method of lens assessment. It should be emphasized that the LOCS III gradings in OHTS were done after the observation group had been on medication for a median of 1.2 years. This may have diminished the difference between the groups.

We utilized the LOCS III grading system to judge lens opacification whereas the Barbados Eye Study6 and the Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial7 used the LOCS II system. The LOCS II and LOCS III grading systems differ principally in that the LOCS III system can detect smaller changes in lens opacification, particularly at the lower end of the grading system.9 The LOCS III system employed in this study should theoretically be more sensitive in detecting early changes than the LOCS II system used in previous studies.

OHTS was designed to assess the efficacy and safety of topical ocular hypotensive medication in delaying or preventing the onset of open-angle glaucoma in ocular hypertensive individuals; however, the design of OHTS did not include serial prospective lens assessment such as clinical lens evaluation, lens photographs, or quantitative measurements, such as LOCS III. Furthermore, we cannot assess whether any specific drug or class of drugs could be associated with cataract formation because many participants in OHTS changed medications during the trial or used more than one medication concurrently to achieve the intraocular pressure goals.

In summary, we find an increased rate of cataract extraction and combined cataract/filtering surgery in ocular hypertensive participants treated with a variety of ocular hypotensive medications. It is possible that these differences arose by chance or by an undetected bias on the part of the clinicians or that topical ocular hypotensive medication initiates or accelerates cataract in a subset of ocular hypertensive individuals. We also find a borderline higher LOCS III grading for posterior subcapsular opacity in the group treated with medication for 8.5 years versus the group treated with medication for 1.2 years; however, we did not find a difference in LOCS III grading for nuclear color, nuclear opalescence or cortical opacity, nor did we find a difference in the rate of change in a variety of visual function measures, refraction and ocular symptoms between the medication and the observation groups. While we find no evidence for an overall effect of medication on measures of lens opacification, it must be emphasized that OHTS was not designed specifically to answer this important question. Given our findings and the findings of the Barbados Eye Study6 and the Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial7 we believe it is important for future investigators to include prospective studies on the effect of all classes of topical ocular hypotensive medication on lens opacification.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants EY09307and EY09341from the National Eye Institute and the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD; Merck Research Laboratories, White House Station, NJ; and unrestricted grants from Research to Prevent Blindness, New York, NY.

Biography

David C. Herman, MD, is an Associate Professor of Ophthalmology at Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and a Consultant in Ophthalmology at May Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota. His clinical and research interests include glaucoma and ocular inflammatory diseases.

Footnotes

Medications were donated by the following pharmaceutical companies: Alcon Laboratories, Inc., Fort Worth TX; Allergan Therapeutics Group, Irvine CA; Bausch & Lomb Pharmaceutical Division, Tampa FL; CIBA Vision Corporation, Duluth GA; Merck Research Laboratories, White House Station, NJ; Novartis Ophthalmics Inc., Duluth MN; Otsuka America Pharmaceutical Inc., Rockville MD; Pfizer, Inc., New York, NY; Pharmacia & Upjohn, Peapack NY, and Santen Inc., Napa, CA.

Conflict of interest: None

For a complete list of authors, refer to the OHTS website: https://vrcc.wustl.edu

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Bernth-Petersen P, Bach E. Epidemiologic aspects of cataract surgery. III: Frequencies of diabetes and glaucoma in a cataract population. Acta Ophthalmol. 1983;61(3):406–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1983.tb01439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Heyningen R, Harding JJ. A case-control study of cataract in Oxfordshire: Some risk factors. Br J Ophthalmol. 1988;72:804–808. doi: 10.1136/bjo.72.11.804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harding JJ, Harding RS, Egerton M. Risk factors for cataract in Oxfordshire: Diabetes, peripheral neuropathy, myopia, glaucoma and diarrhoea . Acta Ophthalmol. 1989;67:510–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1989.tb04101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harding JJ, Egerton M, van Heyningen R, Harding RS. Diabetes, glaucoma, sex, and cataract: analysis of combined data from two case control studies. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993;77:2–6. doi: 10.1136/bjo.77.1.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaffer RN, Rosenthal G. Comparison of cataract incidence in normal and glaucomatous population. Am J Ophthalmol. 1970;69(3):368–370. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(70)92266-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leske MC, Wu SY, Nemesure B, Hennis A Barbados Eye Studies Group. Risk factors for incident nuclear opacities. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:1303–1308. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01094-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heijl A, Leske MC, Bengtsson B, Hyman L, Bengtsson B, Hussein M Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial Group. Reduction of intraocular pressure and glaucoma progression: results from the Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:1268–1279. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.10.1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kass MA, Heuer DK, Higginbotham EJ, Johnson CA, Keltner JL, Miller JP, Parrish RK, Wilson MR, Gordon MO. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: a randomized trial determines that topical ocular hypotensive medication delays or prevents the onset of primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:701–713. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.6.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chylack LT, Jr, Wolfe JK, Singer DM, Leske MC, Bullimore MA, Bailey IL, Friend J, McCarthy D, Wu SY. The Lens Opacities Classification System III. The Longitudinal Study of Cataract Study Group. Arch Ophthalmol. 1993;111:831–836. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1993.01090060119035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gordon MO, Kass MA. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: design and baseline description of the participants. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117:573–583. doi: 10.1001/archopht.117.5.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Axelson U, Holmberg A. The frequency of cataract after miotic therapy. Ophthalmologica. 1966;44:421–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1966.tb08053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaffer RN, Hetherington J., Jr Anticholinesterase drugs and cataracts. Am J Ophthalmol. 1966;62:613–618. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(66)92181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Roeth A., Jr Lens opacities in glaucoma patients on phospholine iodide therapy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1966;61:629–628. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(66)92182-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levene RZ. Uniocular miotic therapy. Trans Sect Ophthalmol Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1975;79(2):OP376–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goto Y, Ibaraki N, Miyake K. Human lens epithelialcell damage stimulation of their secretion of chemical mediators by benzalkonium chloride rather than latanoprost and timolol. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121:835–839. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.6.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chandrasekaran S, Cumming RG, Rochtchina E, Mitchell P. Associations between elevated intraocular pressure and glaucoma, use of glaucoma medications, and 5-year incident cataract: The Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:422–429. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klein BE, Klein R, Moss SE. Incident cataract surgery: The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 1997;104(4):573–80.T. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(97)30267-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klein BE, Klien R, Linton KL. Intraocular pressure in an American community: The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992;33:2224–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]