Abstract

Here we identify the BAP1 and BAP2 genes of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) as general inhibitors of programmed cell death (PCD) across the kingdoms. These two homologous genes encode small proteins containing a calcium-dependent phospholipid-binding C2 domain. BAP1 and its functional partner BON1 have been shown to negatively regulate defense responses and a disease resistance gene SNC1. Genetic studies here reveal an overlapping function of the BAP1 and BAP2 genes in cell death control. The loss of BAP2 function induces accelerated hypersensitive responses but does not compromise plant growth or confer enhanced resistance to virulent bacterial or oomycete pathogens. The loss of both BAP1 and BAP2 confers seedling lethality mediated by PAD4 and EDS1, two regulators of cell death and defense responses. Overexpression of BAP1 or BAP2 with their partner BON1 inhibits PCD induced by pathogens, the proapototic gene BAX, and superoxide-generating paraquat in Arabidopsis or Nicotiana benthamiana. Moreover, expressing BAP1 or BAP2 in yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) alleviates cell death induced by hydrogen peroxide. Thus, the BAP genes function as general negative regulators of PCD induced by biotic and abiotic stimuli including reactive oxygen species. The dual roles of BAP and BON genes in repressing defense responses mediated by disease resistance genes and in inhibiting general PCD has implications in understanding the evolution of plant innate immunity.

Programmed cell death (PCD) is a death program actively executed by the cell. In animals, PCD is a way to sculpt tissues, maintain cell numbers, and remove unwanted or damaged cells (Jacobson et al., 1997). In plants, PCD is an integral part of plant development, occurring throughout the plant's life cycle in processes such as fertilization, xylogenesis, and senescence (Greenberg, 1996). It is also an essential component known as hypersensitive response (HR) during plant-pathogen interactions (Shirasu and Schulze-Lefert, 2000; Greenberg and Yao, 2004). HR occurs in race-specific disease resistance mediated by the host disease R (resistance) gene and the corresponding pathogen avr (avirulence) gene in an allele-specific manner (Flor, 1971). It is characterized by rapid calcium and other ion fluxes, an extracellular oxidative burst, and transcriptional reprogramming (Scheel, 1998). Plants may use an apoptotic machinery similar to those of animals and yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) as similar morphological and biochemical features are shared for PCD in these organisms (Gilchrist, 1998; Beers and McDowell, 2001; Greenberg and Yao, 2004; Lam, 2004). Furthermore, cell death in plants is suppressed by expression of an animal antiapoptosis gene CED9/Bcl-2 (Mitsuhara et al., 1999; Dickman et al., 2001), and an HR-like cell death is induced by the expression of animal proapoptotic genes such as Bax (Lacomme and Santa Cruz, 1999; Mitsuhara et al., 1999; Xu et al., 2004). However, functional equivalents of animal cell death genes have not been readily identified by sequence homology in plants and the regulation and execution of PCD in plants have yet to be understood.

PCD and disease resistance are intricately linked in plants, exemplified by the simultaneous induction of disease resistance and activation of cell death upon pathogen recognition by R proteins. A number of signaling molecules are involved in disease resistance including reactive oxygen species (ROS), salicylic acid (SA), and nitric oxide (Shirasu and Schulze-Lefert, 2000). ROS accumulate preceding cell death during HR, with biphasic oxidative bursts (Lamb and Dixon, 1997). Although ROS have been shown to trigger cell death (Van Breusegem and Dat, 2006), ROS generating NADPH oxidase complex appears to negatively regulate cell death during HR (Torres et al., 2005). SA plays a crucial molecule for systemic acquired resistance (Durrant and Dong, 2004) and it accelerates the rate of cell death in HR and amplifies a sustained oxidative burst (Shirasu and Schulze-Lefert, 2000). R proteins cloned to date largely belong to five protein families (Dangl and Jones, 2001; Martin et al., 2003). Those in the largest family in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) contain a nucleotide-binding (NB) domain and a Leu-rich repeat (LRR) domain at the carboxyl terminus, with either a coiled-coil (CC) domain or a Toll/interleukin-1 receptor (TIR) domain at the amino terminus (Meyers et al., 2003). Although examples of direct physical interaction between Avr and R exist, emerging evidence suggests that the recognition could be indirectly mediated by other plant host proteins. In this guard hypothesis, R proteins may guard or monitor the status of the host plant proteins that are targets of pathogen Avr effector proteins (Martin et al., 2003; Chisholm et al., 2006; Jones and Dangl, 2006).

Genetic studies have identified genes required for R gene signaling (Dangl and Jones, 2001; Glazebrook, 2001). ENHANCED DISEASE SUSCEPTIBILITY1 (EDS1) and PHYTOALEXIN DEFICIENT4 (PAD4) are required for the function of TIR-NB-LRR proteins while NONRACE-SPECIFIC DISEASE RESISTANCE1 (NDR1) is normally required for the CC-NB-LRR proteins although there are exceptions (Wiermer et al., 2005). REQUIRED FOR MLA12 RESISTANCE (RAR1), SUPPRESSOR OF THE G2 ALLELE OF SKP1 (SGT1), and HEAT SHOCK PROTEIN90 (HSP90) modulate R-protein accumulation and signaling competence (Azevedo et al., 2002; Schulze-Lefert, 2004; Holt et al., 2005; Azevedo et al., 2006). Intriguingly, EDS1, PAD4, and NDR1 are implicated in the amplification of cell death and this function appears to be independent from their roles in R-gene-mediated defense responses (Clarke et al., 2001; Rusterucci et al., 2001). Genetic studies have also identified genes for cell death control. A number of mutants classified as lesion mimics induce spontaneous cell death that may result from defects in developmental PCD, HR control, or from necrosis and chlorosis (Shirasu and Schulze-Lefert, 2000). Some of the lesion mimic mutants have misregulation of the initiation of cell death and form small, localized, necrotic spots. More than 30 such mutants have been isolated including some of those in accelerated cell death (acd), constitutive expressor of PR genes (cpr), lesion simulating disease (lsd), and suppressor of SA insensitivity (ssi) in Arabidopsis (Lorrain et al., 2003) and mutation-induced recessive alleles (mlo) in barley (Hordeum vulgare; Buschges et al., 1997). About half a dozen mutants, including some lsd and acd, are unable to control the rate and extent of lesions and form chlorosis in a large area (Lorrain et al., 2003). Most of these lesion mimic mutants have altered defense responses, further indicating an intricate connection between cell death and disease resistance. Understanding how each individual gene modulates cell death is essential to deciphering cell death control and defense pathways.

The Arabidopsis BAP1 gene is involved in defense and cell death regulation. It encodes a membrane-associated protein containing a C2 domain and has a calcium-dependent phospholipid-binding activity (Hua et al., 2001; Yang et al., 2006a). Biochemical and genetic data indicate that BAP1 is a functional partner of BON1, an evolutionarily conserved copine protein with two C2 domains at its amino terminus (Hua et al., 2001; Yang et al., 2006a). BAP1 and BON1 are negative regulators of defense responses. Similar to but less so than the bon1 mutants (Hua et al., 2001; Jambunathan et al., 2001), the bap1 loss-of-function mutants have an enhanced disease resistance to virulent pathogens and consequently dwarfed statures (Yang et al., 2006a). The defense phenotype is mediated by SNC1/BAL, a TIR-NB-LRR type of gene in the RPP5 cluster (Yang and Hua, 2004; Yang et al., 2006a). Though a cognate avr gene has not been identified, SNC1 is likely an R gene as its active mutants induce constitutive defense responses (Stokes et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2003). The bap1 and bon1 phenotypes are reversed by loss-of-function mutations in SNC1, EDS1, and PAD4 as well as by nahG encoding a SA-degrading enzyme (Yang and Hua, 2004; Yang et al., 2006a), indicating that BON1 and BAP1 are negative regulators of the R gene SNC1. The BAP1 and BON1 genes have additional roles other than negatively regulating SNC1. Overexpression of BAP1 confers wild-type plants an enhanced susceptibility to a virulent oomycete in a SNC1-independent manner (Yang et al., 2006a). Furthermore, the loss of function of all BON1 family (BON1, BON2, BON3) results in seedling lethality that is largely suppressed by eds1, pad4, but not by snc1 or nahG (Yang et al., 2006b). Thus, BON1 has an overlapping function with its two homologs in Arabidopsis and their shared function is not totally SNC1 dependent.

The intriguing regulation of a NB-LRR type of R gene and defense responses by membrane-associated proteins BAP1 and BON1 prompted us to further investigate the function of these proteins. In this study, we molecularly and genetically characterized the BAP1 gene and its homolog BAP2 gene in Arabidopsis. Similarly to BAP1, BAP2 interacts with BON1 in the yeast two-hybrid system and its overexpression rescues the bap1 phenotype. Unlike bap1, the bap2 loss-of-function mutant has no apparent growth defects or increased disease resistance. However, it has an accelerated HR in response to avirulent bacterial pathogen. The BAP1 and BAP2 genes have overlapping functions in suppressing cell death, and the loss of both genes in Arabidopsis leads to seedling lethality that can be reverted by pad4 or eds1 mutations. Furthermore, overexpression of BAP1 and BON1 inhibits cell death induced by several R genes, a mouse proapototic gene Bax, and superoxide-generating paraquat in plants. In addition, expressing BAP1 or BAP2 in yeast attenuates cell death induced by hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Thus the BON and BAP genes are likely general repressors of cell death and could therefore be targets of pathogen effectors and guarded by R genes.

RESULTS

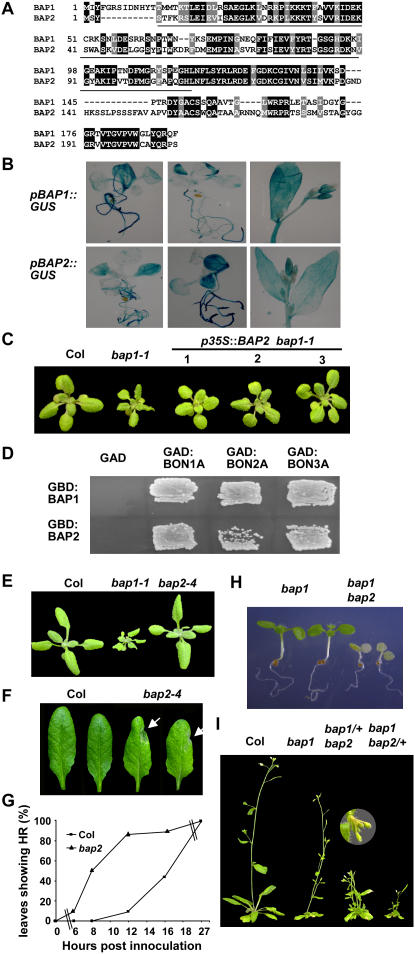

BAP2 Is Homologous to BAP1

Blast search revealed a gene At2g45760 with homology to BAP1 in Arabidopsis and we named it as BAP2. Using reverse transcription-PCR, we isolated a cDNA of BAP2 and found that it encodes a small protein of 207 amino acids containing a C2 domain at the amino terminus and a short segment at the carboxyl terminus. The deduced BAP1 and BAP2 proteins are 54% identical with homology at both the C2 domain and the C-terminal segment (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

BAP2 has an overlapping function with BAP1. A, Alignment of the amino acid sequences of BAP1 and BAP2. Identical residues are shaded in black and similar residues are shaded in gray. The C2 domains are underlined. B, Expression patterns of the BAP1 and BAP2 genes. Shown are representative GUS stainings of transgenic plants containing pBAP1∷GUS and pBAP2∷GUS at the seedling and flowering stages. Note expression in roots, young leaves, stems, and floral buds. C, BAP2 overexpression largely rescues the bap1-1 defect. bap1-1 has a dwarf phenotype compared to the wild-type Col. Shown on the right are three independent transgenic lines carrying p35S∷BAP2 in bap1-1. D, BAP1 and BAP2 interact with BON1, BON2, and BON3 in the yeast two-hybrid system. GBD:BAP1 and GBD:BAP2 are fusions of BAP1 and BAP2 with the GAL4 DNA-binding domain, respectively. GAD:BON1A, GAD:BON2A, and GAD:BON3A are fusions of the A domains of BON1, BON2, and BON3 with the GAL4 activation domain, respectively. Yeast cells containing both the GAD and GBD constructs were patched on SC medium selecting for protein-protein interaction 3 d after streaking. Note the combinations of the BAP proteins with the BON proteins, but not with the GAD vector controls, grow on this medium. E, bap2-4 has no obvious growth defects. Shown are 3-week-old seedlings of the wild-type Col, bap1-1, and bap2-4. F and G, bap2 has an altered HR in response to Pst DC3000 avrRpt2. At 8 hpi, most of the bap2 leaves but not the Col leaves exhibited HR indicated by white arrows (F). The percentage of leaves exhibiting HR is shown during the course of 30 h after inoculation (G). Replicated experiments yielded a similar alteration. H, The bap1bap2 double mutant is seedling lethal. Shown are seedlings several days after germination. The two on the left are the bap1 single mutants and the two on the right are the bap1bap2 double mutants. I, bap1 and bap2 have dominant interactions. Shown are plants after bolting. bap1bap2/+ and bap1/+bap2 have more severe phenotype than the bap1 and the bap2 single mutants, respectively. Insert shows a bended and yellow inflorescence stem in bap1/+bap2.

RNA-blot analysis indicates that BAP2 is expressed at a lower level than BAP1 (data not shown), which is consistent with the transcriptional profiling data available from The Arabidopsis Information Resource links (http://Arabidopsis.org/). BAP2 is under a similar regulation at the transcript level as BAP1. Both genes are up-regulated by infections from Botrytis cinerea, nematode, and Pseudomonas syringae, treatments of chemicals (AgNO3, chitin, cycloheximide, ozone, syringolin), and salt stress. They are also both up-regulated in the loss-of-function bon1-1 mutant (referred as bon1 from now on) and have a higher expression level at lower temperatures (Yang et al., 2006a; data not shown).

To assess the spatial expression pattern of BAP2, we fused the promoter of BAP2 with the GUS reporter gene and generated transgenic plants carrying pBAP2∷GUS. GUS staining of representative transgenic lines showed that pBAP2∷GUS was ubiquitously expressed throughout the plants including leaves, stems, roots, and inflorescences, with higher activities in relatively young tissues (Fig. 1B). This pattern resembles that of pBAP1∷GUS (Fig. 1B), suggesting that the BAP1 and BAP2 genes have similar spatial expression domains.

To determine whether BAP2 has a similar biochemical function to BAP1, we expressed BAP2 in the loss-of-function bap1-1 mutant (referred as bap1 from now on) under the control of the strong constitutive 35S promoter of cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV). While bap1 has small and curly leaves compared to the wild-type Columbia-0 (Col-0; referred as Col from now on), p35S∷BAP2 transgenic lines in bap1-1 are essentially wild type in appearance (Fig. 1C), indicating that the BAP2 protein has a similar biochemical activity to BAP1.

Previous studies demonstrated that the BAP1 protein interacts with the BON1 protein in vitro and that they likely act as partners in vivo (Hua et al., 2001; Yang et al., 2006a). We asked whether BAP2 can interact with BON1 as well by using the yeast two-hybrid system (Fields and Song, 1989). BAP1 and BAP2 were each fused to the DNA-binding domain of the GAL4 transcription factor to generate GBD:BAP1 and GBD:BAP2 fusion proteins, respectively, while the A domain of BON1 was fused with the activation domain of GAL4 to generate GAD:BON1A. Coexpression of GBD:BAP2 with GAD:BON1A conferred growth to the yeast host strain on medium selecting for protein-protein interactions, similarly to that of GBD:BAP1 and GAD:BON1A (Fig. 1D), indicating a direct interaction between the BON1 and BAP2 proteins.

Because BON2 and BON3 have overlapping functions with BON1 (Yang et al., 2006b), we further determined whether BAP1 and BAP2 can interact with BON2 or BON3 in the yeast two-hybrid system. Coexpression of GBD:BAP1 or GBD:BAP2 with GAD:BON2A and GAD:BON3A, respectively, conferred yeast growth on the selection medium (Fig. 1D). It thus appears that each member of the BON family can interact with each member of the BAP family. Assessed by yeast growth, the strength of interaction differs among these protein pairs, with the weakest interaction found between BAP2 and BON2 and the strongest one found between BON1 and BAP1. These differences are yet to be validated with the analysis of expression and stability of these proteins in yeasts.

The Loss of BAP1 and BAP2 Function Confers Seedling Lethality

To elucidate the function of BAP2, we isolated a T-DNA insertion mutant of BAP2 (SALK_052789) from the SALK collection. The T-DNA was inserted in the nucleotide sequence corresponding to Gln 67 of the encoded BAP2 protein (Fig. 1A), and no BAP2 transcript was observed by RNA-blot analysis (data not shown). This loss-of-function mutant, named as bap2-4 (referred as bap2 from now on), did not exhibit any obvious growth defects, in contrast to the bap1 mutant (Fig. 1E). However, an accelerated HR was observed in bap2 compared to Col for P. syringae pv tomato (Pst) DC3000 expressing AvrRpt2. Col wild type and bap2 were inoculated with a high concentration of Pst DC3000 carrying avrRpt2. At 8 h postinoculation (hpi), none of the Col leaves showed HR, while 50% of the bap2 leaves already had HR at this time (Fig. 1, F and G). At 12 h, 90% of the bap2 leaves exhibited HR while only 10% of the wild-type leaves showed HR (Fig. 1G).

To reveal possible overlapping functions between BAP1 and BAP2, we attempted to generate double mutants between bap2 and bap1. However, plants with the bap1bap2 genotype could not be identified from the F2 progenies of a cross between bap1 and bap2, suggesting that the homozygous mutant is either embryonic or seedling lethal. We subsequently sowed the progenies of double mutants (one heterozygous and the other homozygous) on agar plates, and found 39 out of 164 bap1bap2/+ and 52 out of 194 from bap1/+bap2 seeds germinated but soon died at the cotyledon stage (Fig. 1H). Again, no surviving seedlings were bap1bap2, confirming that the double mutant is seedling lethal.

We observed dominant interactions between the bap1 and bap2 mutants. bap1 is a recessive mutant with a mild growth defect (Yang et al., 2006a) and bap2 has no obvious growth defect. However, heterozygous mutants of bap1 and bap2 each enhanced the phenotypes of the homozygous mutants of the other (Fig. 1I). The bap1/+bap2 mutant had small and slightly curly leaves in contrast to the wild-type-looking bap2 mutant. After bolting, its primary shoot frequently bended at the tip and died afterward. Multiple lateral shoots usually generated subsequently, giving a bushy phenotype. The bap1bap2/+ mutant exhibited a stronger phenotype than the bap1 single mutant. Its leaves are very curly with water-soaked appearance, resembling those of bon1. The genetic interactions between BAP1 and BAP2 indicate that these two genes have overlapping functions and that their functions are dosage dependent.

Cell Death Occurs in Mutant Combinations between bap1 and bap2

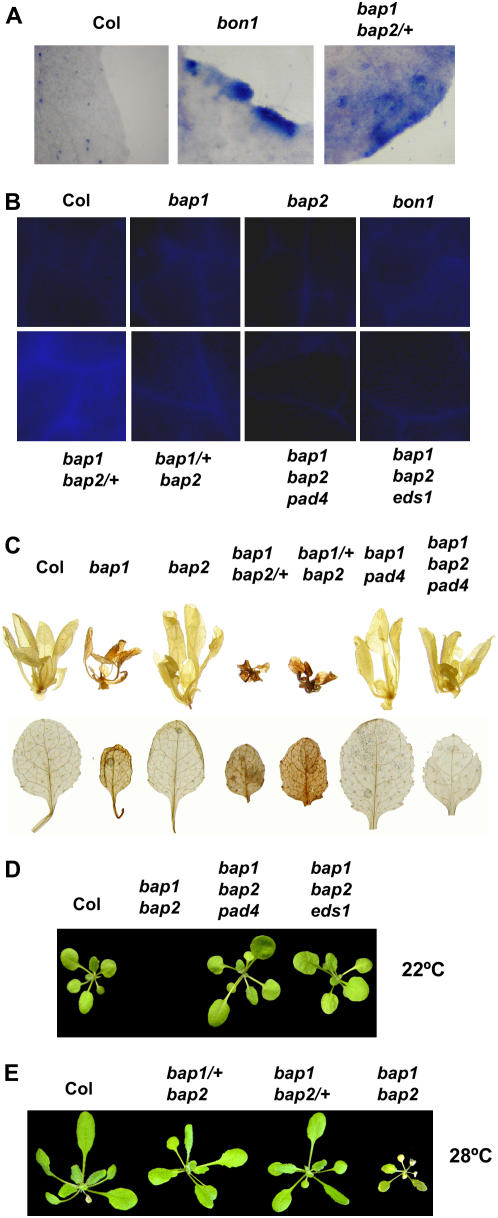

We assessed cell death in different mutant combinations between bap1 and bap2 as their double homozygous mutant is seedling lethal. Trypan blue, a membrane impermeable reagent, was used to stain dead cells or cells with damaged cell membranes. This vital stain revealed various degrees of cell death in leaves of different mutants (Fig. 2A). None of the wild-type Col leaves (0/8) analyzed had any staining, neither did the bap1 (0/8) or the bap2 (0/8) single mutants. Strong staining was found in most of the leaves of bon1-1 (9/14), consistent with previous findings (Jambunathan et al., 2001; Yang et al., 2006b). Very few leaves of bap1/+bap2 (1/8) were stained by trypan blue, while most of the bap1bap2/+ leaves (7/12) were stained. Thus, extensive cell death occurs in leaves of bap1bap2/+ as in bon1, correlating with a severe morphological defect in leaves.

Figure 2.

Cell death occurs in bap1 and bap2 mutant combinations. A, Trypan blue staining of representative leaves of Col, bon1, and bap1bap2/+. In contrast to wild-type Col and the bap1 and bap2 single mutants (data not shown), bap1bap2/+ has a strong trypan blue staining similar to bon1. B, Autofluorescence of leaves from Col, bap1, bap2, bon1, bap1bap2/+, bap1/+bap2, bap1bap2pad4, and bap1bap2eds1. bap1bap2/+ has the strongest autofluorescence while the bap1 and bap2 single mutants have no significant amount. Autofluorescence is absent in bap1bap2pad4 and bap1bap2eds1. C, Accumulation of H2O2 in various mutants. Top section shows DAB staining of 2-week-old plants grown under constant lights and the bottom section shows DAB staining of individual leaves from plants grown under 12 h light and 12 h of darkness. Note the weak staining in bap1, a strong staining in bap1bap2/+, bap1/+bap2, but no staining in wild-type Col, bap2, bap1pad4, or bap1bap2pad4. D, Both pad4 and eds1 rescued the lethal phenotype of bap1bap2. Shown are 3-week-old seedlings of the wild-type Col, bap1bap2pad4, and bap1bap2eds1 grown at 22°C. bap1bap2 was dead at this stage. E, High temperature partially rescued the bap1bap2 mutant phenotype. Shown are 3-week-old seedlings of the wild-type Col, bap1/+bap2, bap1bap2/+, and bap1bap grown at 28°C. Note bap1bap2/+ and bap1/+bap2 are wild-type looking and bap1bap2 is surviving but yellowing at this stage.

We further analyzed leaves of these mutants for autofluorescence indicative of accumulation of phenolic compounds from dead cells. No significant autofluorescence was observed in Col, bon1, bap1, bap2, or bap1/+bap2 (Fig. 2B). In contrast, strong autofluorescence was found in bap1bap2/+ (Fig. 2B), indicating extensive cell death in bap1bap2/+.

We then asked whether the cell death phenotype in bap1 and bap2 mutant combinations was associated with an accumulation of ROS. To this end, we determined the relative amount of H2O2 in mutant plants by diaminobenzidine (DAB) that forms reddish brown precipitates when reacted with H2O2. Under growth conditions of both constant light and 12-h light/12-h darkness, bap1, but not bap2, had a darker staining compared to the wild-type Col. bap1/+bap2 and bap1bap2/+ both had a stronger staining than bap1 (Fig. 2C). Thus, H2O2 accumulates at a moderate level in bap1 and at a higher level in the bap1 and bap2 mutant combinations.

Modulation of the bap1bap2 Double Mutant Phenotypes by eds1, pad4, and the Environment

The lethal phenotype of bap1bap2 could result from a heightened defense response leading to extensive cell death at very early stage of development. We assessed whether the lethal phenotype of bap1bap2 is due to a stronger activation of SNC1 and higher accumulation of SA in the double mutant than in the bap1 single mutant, given that the loss-of-function mutant snc1-11 (referred as snc1 from now on) and the SA-degrading nahG suppressed the phenotype of bap1. Analysis of progenies of a bap1bap2/+snc1/+ plant and those of a bap1bap2/+nahG/+ plant indicate that neither snc1 nor nahG could rescue the lethal phenotype of bap1bap2 (data not shown).

Strikingly, the lethality of bap1bap2 can be suppressed by mutations in PAD4 or EDS1. From the F2 progenies of a cross between bap2 and bap1pad4 (Yang et al., 2006a), we were able to obtain bap1bap2 plants and these plants were always pad4 homozygous, indicating that pad4 suppressed the lethal phenotype of bap1bap2. Not only was the triple mutant bap1bap2pad4 viable, it was also wild type in appearance throughout its development (Fig. 2D). Similar rescue of lethality of bap1bap2 was observed with the eds1 mutation as well (Fig. 2D).

pad4 and eds1 suppressed all other mutant phenotypes observed in the bap1 and bap2 mutant combinations. No autofluorescence could be seen on leaves of bap1bap2pad4 or bap1bap2eds1, in contrast to the strong fluorescence on the bap1bap2/+ leaves (Fig. 2B). Nor was a higher level of DAB staining observed in bap1bap2pad4, indicating a suppression of H2O2 accumulation in bap1bap2 by pad4 (Fig. 2C).

We determined whether environmental factors can modulate the phenotypes of the bap1 and bap2 mutant combinations. A higher temperature of 28°C alleviates the growth defects observed in all double mutants to different degrees. Both bap1bap2/+ and bap1/+bap2 were wild-type looking throughout the life cycle at 28°C in contrast to the dwarf phenotype at 22°C (Fig. 2E). The bap1bap2 homozygous mutant was partially rescued by a higher growth temperature. Instead of dying immediately after germination at 22°C, the double mutant grew like the wild type at 28°C for 2 weeks after germination. However, when the wild type started bolting at approximately 3 weeks old, the double mutant turned yellow and died (Fig. 2E).

A shorter photoperiod suppressed phenotypes of some of the mutant combinations as well. bap1/+bap2 and bap1bap2/+ grown under a cycle of 12-h light and 12-h darkness rather than constant light were wild-type looking (data not shown). However, no bap1bap2 could be found from progenies of bap1/+bap2 or bap1bap2/+ under this growth condition, indicating that the shorter photoperiod does not suppress the seedling lethality of bap1bap2.

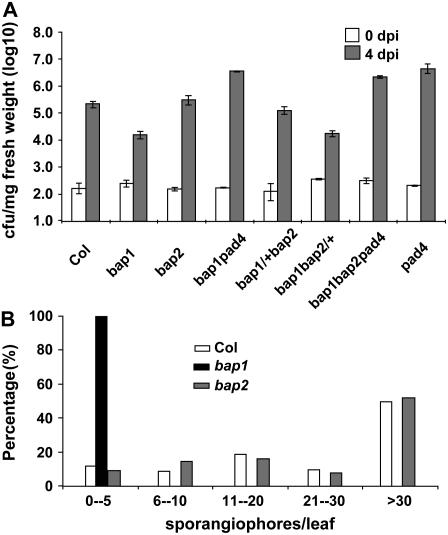

The bap2 Cell Death Phenotype Is Not Associated with Defense Responses

Because bap1 has heightened disease resistance to virulent P. syringae and Hyaloperonospora parasitica (Yang et al., 2006a), we assessed whether bap2 has an abnormal defense response. We challenged the bap2 mutant with a virulent bacterial pathogen Pst DC3000 and found that it was as susceptible to this pathogen as the wild-type Col (Fig. 3A). Four days after infection, Pst grew to 4.2 × 105 colony forming units (cfu) mg−1 fresh weight in bap2, similarly to the level of 3 × 105 in the wild type, while its growth was reduced to 1.1 × 104 in bap1. bap2 was also as susceptible to virulent H. parasitica as the wild type. While no sporangiphores were found on bap1 a week after spray inoculation, bap2 supported the same amount of growth of this pathogen as the wild-type Col (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

The bap2 mutant does not have an enhanced disease resistance. A, bap2 is susceptible to Pseudomonas syringe pv tomato DC3000. Plants were infected with Pst DC3000 and the amount of bacterial growth in the leaves was determined at 0 and 4 d post inoculation (dpi). Bacterial growth was inhibited in bap1 but not in bap2 compared to the wild-type Col. bap1/+bap2 and bap1bap2/+ had approximately the same amount of growth as bap2 and bap1, respectively. bap1bap2pad4 supports the same amount of bacterial growth as the pad4 single mutant. B, bap2 is susceptible to virulent growth of Hyalopernonspora parasitica. H. parasitica Noco2 strain was used to infect Col, bap1, and bap2. Shown is the distribution of the number of sporangiophores per leaf formed a week later for each genotype. In contrast to bap1, bap2 had the same amount of sporangiophore formation as the wild-type Col.

Given that bap1 and bap2 enhanced each other's morphological and cell death phenotype in a dominant manner, we asked whether the same is true for the disease resistance phenotype. Growth of Pst DC3000 was analyzed in the bap1/+bap2 and bap1bap2/+ mutants. Pst propagated to 1.8 × 104 cfu mg−1 fresh weight in bap1bap2/+, comparable to the level of 1.1 × 104 in bap1 (Fig. 3A), indicating that bap2 does not dominantly enhance disease resistance in bap1. Pst grew to 1.3 × 105 in bap1/+bap2, similar though slightly lower than the level of 4.2 × 105 in bap2 (Fig. 3A). No significant difference was observed in biological replica between bap1/+bap2 and bap2. Thus, bap1 and bap2 do not dominantly enhance each other's disease resistance phenotype in contrast to the growth and cell death phenotype. In addition, bap1bap2pad4 was as susceptible to Pst as pad4 and bap1pad4 (Fig. 3A), indicating that the resistance phenotype is mediated by PAD4.

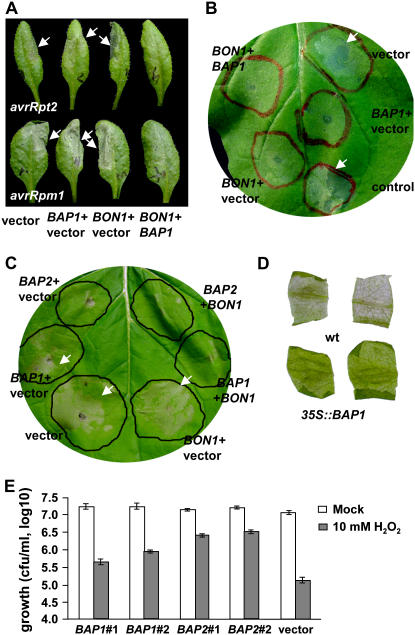

Overexpression of BAP and BON Genes Inhibits PCD Induced by a Variety of Biotic and Abiotic Stimuli in Plants

The loss-of-function phenotypes indicate that the BAP genes are negative regulators of cell death. To determine whether they have a direct role in suppressing cell death, we analyzed their overexpression effect on PCD. First we assayed HR induced by Pst DC3000 carrying avirulent effectors in Arabidopsis. Wild-type Col plants were infiltrated with Pst DC3000 (avrRpt2) together with Agrobacterium containing p35S∷BON1, p35S∷BAP1, or an empty vector. At 14 hpi, a strong HR indicated by the collapse of tissues appeared on all leaves inoculated with Pst DC3000 (avrRpt2) together with the vector control (Fig. 4A). Agroinfiltrations with p35S∷BAP1 or p35S∷BON1 did not affect HR when compared to the vector control, although they occasionally slightly delayed its onset. In contrast, HR was not observed at 14 hpi when p35S∷BAP1 and p35S∷BON1 were simultaneously agroinfiltrated (Fig. 4A), and it only started to develop at approximately 18 hpi, indicating that BAP1 and BON1 together inhibited HR induced by avrRpt2.

Figure 4.

Overexpression of BAP1 and BAP2 suppresses PCD. A, BAP1 and BON1 together suppress HR triggered by Pst DC3000 harboring avrRpt2 and avrRpm1. DC3000 strains were inoculated on Arabidopsis leaves to induce HR indicated by the collapse of cells (marked by white arrows). p35S∷BAP1, p35S∷BON1, or an empty vector were agroinfiltrated together with DC3000. Shown are leaves 8 hpi for avrRpm1 and 17 hpi for avrRpt2. Combination of p35S∷BAP1 and p35S∷BON1 significantly inhibits HR induced by both AvrRpt2 and AvrRpm1. p35S∷BAP1 appears to have a weak suppression of HR induced by AvrRpt2, but it was not consistently observed. B, Both BON1 and BAP1 inhibit HR induced by the R protein Rx in N. benthamiana. Rx and its effector CP were agroinfiltrated on leaves (marked by red circles) to induce HR. Except for the control area, all other areas were coagroinfiltrated with BON1, BAP1, or the empty vector singly or combined with the same total amount of Agrobacterium cells in each infiltrated area. Shown is a representative leaf at 60 hpi. Note the cell collapse in the vector and the control areas (indicated by white arrows). C, BAP1 and BAP2 suppress Bax-induced cell death in N. benthamiana. Leaf areas marked by black circles were agroinfiltrated with pDEX∷Bax and Bax expression was induced by spraying the whole leaf with DEX. These areas were also agroinfiltrated with BAP1, BAP2, BON1, and the empty vector either singly or combined with the same total amount of agrobacteria for each area. Shown is a representative leaf at 72 hpi. Cell death occurred in area coinfiltrated with the vector control, BON1, and BAP1 singly (indicated by white arrows). Cell death is slightly suppressed by BAP2 and is greatly suppressed by coexpression of BAP1 or BAP2 together with BON1. D, BAP1 overexpression confers paraquat resistance. Leaf discs from the wild-type Col and 35S∷BAP1 transgenic plants were floated on paraquat solution (4 μm) for 2 d before pictures were taken. E, Yeast strains transformed with BAP1, BAP2, or the empty vector pAD4M were treated with 10 mm of H2O2 or water (mock). Shown is the amount of live cells 12 h after treatment in two BAP1, two BAP2, and one vector transformants from three replicates. BAP1 and especially BAP2 greatly increased the survival rates of yeast cells treated with H2O2.

We additionally tested the effect of BAP1 and BON1 overexpression on HR induced by another avirulent strain Pst DC3000 (avrRpm1). At 5 to 6 hpi, a strong HR was induced by avrRpm1 when agroinfiltrated with the vector control. Agroinfiltration with p35S∷BAP1 or p35S∷BON1 alone did not significantly affect the development of HR. However, HR was not observed until 8 to 9 hpi with simultaneous agroinfiltration of BAP1 and BON1 (Fig. 4A). The suppression for both avirulent strains was consistently seen in replicated experiments. Therefore, overexpression of BON1 and BAP1 together in Arabidopsis greatly delayed HR induced by avirulent bacterial pathogen Pst DC3000 with two different effector proteins.

We subsequently analyzed the effect of overexpression of BAP1 and BON1 on PCD induced by other R proteins. Transient coexpression of a potato (Solanum tuberosum) NB-LRR type of R protein Rx and its elicitor PVX coat protein (CP) was shown to induce HR in Nicotiana benthamiana (Bendahmane et al., 2000). A collapse of cells indicative of HR was observed in leaf area agroinfiltrated with Rx and CP at 36 hpi. Coagroinfiltration with the vector alone did not alter the onset or the progression of HR. However, when p35S∷BAP1 or p35S∷BON1 were coagroinfiltrated, HR was either suppressed or greatly reduced at 36 hpi (Fig. 4B). In some repeats, no HR was ever developed over the following 5 d observation. Coagroinfiltration of p35S∷BAP1 and p35S∷BON1 together did not appear to have a stronger effect in HR suppression.

Given that BAP1 and BON1 inhibit HR induced by R proteins, we further tested whether the BAP1 and BON1 genes can suppress PCD induced by reagents other than R proteins in plants. The mouse Bax gene belongs to the apoptotic Bcl-2 family and is shown to induce cell death response in plants resembling HR (Lacomme and Santa Cruz, 1999; Kawai-Yamada et al., 2001; Abramovitch et al., 2003). We infiltrated leaves of N. benthamiana with Agrobacterium containing the Bax gene under the control of a dexamethasone (DEX) inducible promoter (pDEX∷Bax; Kawai-Yamada et al., 2001) and induced Bax expression by spraying the inoculated leaves with DEX. Cell death occurred at 72 hpi, manifested by a transparent and collapsed infiltrated area (Fig. 4C). Coagroinfiltration with either p35S∷BAP1 or p35S∷BON1 did not consistently affect the rate or extent of cell death compared to the vector control. p35S∷BAP2, however, sometimes inhibited Bax-induced cell death at 72 hpi (Fig. 4C). Strikingly, when p35S∷BAP1 and p35S∷BON1 were simultaneously agroinfiltrated with pDEX∷Bax, no obvious cell death was observed at 72 hpi when the control areas exhibited strong cell death (Fig. 4C). Similar suppression of cell death was observed when p35S∷BAP2 and p35S∷BON1 were coagroinfiltrated. In both cases, cell collapse started at 90 hpi and occurred to a full extend at 114 hpi in BON1 and BAP1/BAP2 coinfiltrated areas. Therefore, Bax-induced cell death was delayed by 1 to 2 d with overexpression of BON1 together with BAP1 or BAP2.

BAP1 and BAP2 Inhibit Cell Death Induced by ROS in Arabidopsis and Yeast

The BAP transcripts are induced by a number of biotic and abiotic stimuli and the common feature of these treatments is probably ROS. Considering that they are capable of inhibiting PCD, we asked whether overexpression of the BAP genes can inhibit cell death induced by ROS. To this end, we compared Col Arabidopsis lines containing the 35S∷BAP1 transgene (Yang et al., 2006a) to the wild-type Col in paraquat sensitivity. Paraquat is a redox-active compound that generates superoxide anion in the cell, causing cell damage and cell death (Tsang et al., 1991). We found that overexpression of the BAP1 gene protects cells from these damages. Wild-type leaf discs treated with paraquat had chlorophyll loss and cholorosis over 2 d, while leaf discs of 35S∷BAP1 transgenic lines stayed green under the same treatment (Fig. 4D), indicating a protective role of BAP1 against ROS.

We further asked whether the BAP genes can protect nonplant species from ROS-induced cell death. We expressed the BAP1 and BAP2 genes under the control of the constitutive ADH promoter in yeast, and assayed their effects on cell death induced by ROS. Yeast cells were treated with 10 mm of H2O2 to induce PCD and cell survival rates were counted 12 h after the treatment. Only 1% of cells containing an empty vector survived the H2O2 treatment compared to the mock treatment (Fig. 4E). In contrast, cells expressing either BAP1 or BAP2 had significantly higher survival rates (Fig. 4E). A total of 2.6% and 4.9% of cells survived for two independent BAP1-expressing strains, respectively, while 18.2% and 20.4% of cells survived for two independent BAP2-expressing strains, respectively. The increase in survival rates by expressing BAP1 and more so by BAP2 was observed in repeated experiments treated with 10 mm of H2O2 as well as in similar experiments treated with 5 mm of H2O2 (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Interaction among the BAP and BON Genes

In this study, we characterized the function of BAP1 and BAP2, two homologous genes encoding small C2 domain-containing proteins. In contrast to the single bap1 mutants that exhibit a constitutive defense response phenotype, the bap2 single mutant does not show any obvious growth defects or enhanced disease resistance. bap2 did exhibit an accelerated HR to an avirulent Pseudomonas strain, suggesting that BAP2 has a role in modulating PCD. Furthermore, the bap1bap2 double mutant is seedling lethal and the heterozygous mutant of one gene can enhance the homozygous mutant of the other. These genetic interactions indicate that BAP1 and BAP2 have unequal redundancy with BAP1 playing a major role. They also indicate that the amount of activities conferred by BAP1 and BAP2 are critical for the process they regulate. This activity decreases roughly in the order of BAP1BAP2, BAP1bap2/+, BAP1bap2, bap1/+BAP2, bap1/+bap2/+, bap1/+bap2, bap1BAP2, bap1bap2/+, and bap1bap2, and it correlates with an increase in morphological phenotypic severity from wild type to lethality. Considering that expressing BAP2 under the CaMV 35S promoter rescued the bap1 single mutant phenotype, we suspect that the BAP2 might have a lower biological activity than BAP1 in terms of the protein amount, protein expression domain, and/or protein activity.

Molecular genetic analysis in this study supports the previous model that BAP1 is a functional partner of BON1, and it further indicates that the BAP proteins are functional partners of the BON proteins. Overexpressing BAP1 and BON1 together but not singly inhibits HR induced by avirulent Pst and cell death induced by Bax, indicating that the BAP1 and BON1 proteins work together to modulate cell death. In addition, the loss of the BAP family function results in seedling lethality similarly to the loss of the BON family function, and the lethality can both be suppressed by eds1 and pad4. Thus the BAP1 family and the BON1 family carry similar functions. Nevertheless, the suppression by eds1 and pad4 is more complete for bap1bap2 than for bon1bon2bon3, suggesting that the BON genes might play a greater role than the BAP genes in Arabidopsis.

The fact that BAP1 and BON1 proteins could interact with each other raises the question whether there are specific pairs of interaction between the BON proteins and the BAP proteins. The yeast two-hybrid assay demonstrated that each protein of the BON family can interact with each member of the BAP family although some interactions appear to be stronger than others. This suggests that in plants there could be multiple interactions between the BON and BAP proteins. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that the bon1bap1 double mutant has a stronger phenotype than the bon1 or bap1 single mutants (H. Yang and J. Hua, unpublished data). Thus BAP1 and possibly BAP2 associate in a functional manner with BON2 or BON3 in addition to the BON1 protein in plants. In addition, promoter-GUS analyses of the BON1 family and the BAP1 family indicate some overlapping expression domains of these genes (Yang et al., 2006b). Therefore, multiple protein complexes might form between BON and BAP proteins to provide robustness and/or specificities to the system.

Regulation of Cell Death and Defense by the BAP and BON Proteins

In this study, we identified a more direct role of the BAP family in the control of PCD across the kingdoms. The loss of function of some of the BAP and BON genes (singly or in combination) leads to microlesions, accelerated HR, or lethality, implicating them as negative regulators of cell death. Quite a few negative regulators of cell death have been identified based on the phenotype of lesions induced by their loss-of-function mutants. However, the regulation could formally be indirect as some lesion mimic mutants are shown to result from the perturbation of metabolic pathways (Mittler et al., 1995; Molina et al., 1999). rin4, bon1, and bap1 are the few known to result from activation of specific R genes (Axtell and Staskawicz, 2003; Mackey et al., 2003; Yang and Hua, 2004; Yang et al., 2006a). It is thought that plant host genes such as RIN4 are targeted by plant pathogens and are subsequently monitored or guarded by R genes (Jones and Dangl, 2006). Some other cell death regulators such as MLO, though not implicated in specific R gene regulation, might also be targeted and manipulated by pathogens (Panstruga, 2005). Understanding the cellular function of these host target genes is of great interest in light of the evolution of plant innate immunity. Here we found a direct role of BAP and BON genes in inhibiting PCD by showing that PCD induced by a variety of reagents can be inhibited by overexpression of BAP and BON genes in different species across the kingdoms. These include HR induced by bacterial effector proteins AvrRpt2 and AvrRpm1 in Arabidopsis, HR induced by the R protein Rx in N. benthamiana, PCD induced by a mammalian apotopic Bax gene, and ROS-generating chemical paraquat. More strikingly, cell death in yeast induced by H2O2 is inhibited by BAP1 and BAP2. The effect of overexpression on diverse PCD indicates that the BON and BAP genes may modify a common component of PCD shared by different organisms. The BAP genes may act downstream of the production of H2O2 in PCD, indicated by their suppression of H2O2-induced cell death in yeast. It is supported by the observation that overexpression of BAP1 and BON1, though inhibits HR, did not appear to alter the onset of H2O2 production during Bax-induced cell death (Y. Li and J. Hua, unpublished data).

Direct regulators and executors of PCD in plants have also been identified by their PCD suppressing activity when they are overexpressed in animals, yeasts, and plants. These include an endoplasmic reticulum-associated BAX INHIBITOR-1 (BI-1; Kawai-Yamada et al., 2001; Watanabe and Lam, 2006; Ihara-Ohori et al., 2007), a transcription factor AtEBP (Pan et al., 2001; Ogawa et al., 2005), a vesicle-associated protein VAMP (Levine et al., 2001), and an AGC kinase Adi3 (Devarenne et al., 2006). These proteins possess a diverse variety of biochemical activities and localize to different cellular compartments, suggesting the involvement of many biochemical and cellular processes in regulating or executing PCD. The BAP1 and BON1 proteins are membrane associated and they possess a calcium-dependent phospholipid-binding activity. The BAP and BON proteins could be potentially functionally connected with AtBI-1 that was shown to interact with calmodulin and maintain calcium homeostasis. They might also work closely with VAMP as C2 proteins often play a role in membrane trafficking. Further investigation of the inhibitory activity of cell death by BON1 and BAP1 should generate insights into regulation of PCD in plants.

The BAP and BON genes appear to be unique among these direct repressors of PCD in that they are implicated in regulating specific NB-LRR type of R-like genes as well. Their loss-of-function mutants exhibit enhanced disease resistance to a variety of virulent pathogens through activating R genes. For instance, the loss of BON1 function leads to enhanced resistance via activating an accession-specific TIR-NB-LRR gene SNC1 (Yang and Hua, 2004), indicating that the BON1 protein could be monitored (guarded) by the R SNC1 gene. No other genes with a direct PCD suppressing activity when overexpressed have yet been identified as being monitored by specific R genes. Overexpression of BI-1 from barley weakened resistance conferred by the mlo mutation and an R gene MLA12 to a fungal pathogen Blumeria graminis (Eichmann et al., 2006). This is likely due to its general effect on H2O2 burst and it is yet to be determined whether or not the loss of BI-1 function will specifically trigger the activation of specific R genes like MLA12.

The dual function of BAP and BON genes in cell death and defense responses, similarly observed in MLO and lsd among others, probably reflects an intrinsic relationship between these two processes as exemplified by HR being an integral part of most of the R-mediated disease resistance. We favor the model that the BAP and BON genes have an ancient role in cell death control and an evolved role in plant defense response. This is consistent with the BON genes as members of the copine gene family found not only in plants but also in animals. It is unclear whether or not the BAP genes are evolutionarily conserved because the most significant signature of their encoded proteins is the C2 domain that is widely present in many signaling molecules. The striking feature of BAP1 is its extreme responsiveness to numerous biotic and abiotic stimuli ranging from singlet oxygen species, temperature variation, wounding from bacterial infection, to even butterfly egg oviposition (op den Camp et al., 2003; Yang et al., 2006a; Little et al., 2007). BAP2 and BON1 respond to at least some of these stimuli but apparently to a lesser degree. The responsiveness to diverse stimuli suggests that the BAP and BON genes may serve as signaling molecules or maintain calcium or lipid homeostasis in stress responses, and the loss of these activities results in cell death. The suppression of the bap and bon phenotypes by eds1 or pad4 indicates that BAP and BON genes regulate a cell death pathway mediated by EDS1 and PAD4. Emerging evidence has strongly implicated EDS1 and PAD4 in transducing redox signals (Mateo et al., 2004; Ochsenbein et al., 2006). It is tempting to speculate that the BAP and BON genes are responsive to ROS and/or calcium signals and modulate ROS signaling in stress responses.

The BAP and BON molecules might become targets of pathogen effector proteins because of their ancestral role in cell death control during the evolution of plant innate immune system (Jones and Dangl, 2006). Indeed, the bon1 and bap1 mutants have heightened defense responses that are at least partially mediated by a TIR-NB-LRR type of R gene SNC1. It is possible that the loss of the BON1 or BAP1 proteins is interpreted by plants as the result of the invasion of a pathogen and thus triggers the activation of R proteins to mount defense responses. Multiple R genes in addition to SNC1 are likely regulated by the BON family and the BAP family, as the bon1bon2, bon1bon3, and bap1bp2 double mutants have stronger phenotypes independent of SNC1 than the bon1 or bap1 single mutants. In addition, the bon or bap mutant combinations exhibit phenotypic variations in different accession backgrounds (Yang et al., 2006b; J. Hua, unpublished data), suggesting the involvement of multiple accession-specific R genes. It has yet to be determined whether the regulation of BON and BAP proteins on R proteins is similar to that of RIN4 on RPM1 and RPS2. Current data do not distinguish models of regulation at the protein level or the RNA transcript level. Future studies on the general PCD inhibitor BAP and BON genes should shed light not only on the regulation of defense responses in plants but also PCD in other kingdoms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material and Growth Conditions

Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) plants were grown at 22°C or 28°C under continuous fluorescent light (100 μmol m−2 s−1) with 50% to 70% relative humidity unless specified otherwise. Arabidopsis seeds were either directly sowed on soil or selected on plates before being transferred to soil. For bacterial pathogen tests, plants were grown at 22°C under a photoperiod of 12 h of light for 2 weeks (for dipping inoculation) or 1 month (for infiltration inoculation).

The bap2-4 mutant was isolated from the Salk T-DNA collection (http://signal.salk.edu/cgi-bin/tdnaexpress). The T-DNA insertion site was confirmed by sequencing PCR products amplified from the mutant with T-DNA primers and gene-specific primers.

Yeast Two-Hybrid Analysis

BAP1 and BAP2 were each fused with the DNA-binding domain of the GAL4 transcription factor in the yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) vector pGBD-C2 with a Trp auxotroph marker (James et al., 1996). The A domains of BON1, BON2, and BON3 were each fused with the activation domain of GAL4 in the yeast vector pGAD-C2 with a Leu auxotroph maker (James et al., 1996). pGBD:BAP1 and pGBD:BAP2 were each cotransformed with pGAD:BON1A, pGAD:BON2A, and pGAD:BON3A, respectively, into the yeast strain PJ69-4 (James et al., 1996). Transformants with both the GBD and GAD constructs were selected on synthetic complete (SC) medium without Trp and Leu. Protein interactions were assayed by growing the transformants on SC medium without adenine, His, Trp, and Leu.

RNA-Blot Analysis

Total RNAs were extracted from 3-week-old plants using TriReagents (Molecular Research) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Twenty micrograms of RNA for each sample were resolved on 1.2% agarose gels containing 1.8% formaldehyde. Ethidium bromide was used to visualize the rRNA bands to ensure equal loading. RNA gel blots were hybridized with gene-specific, 32P-labeled, single-stranded DNA probes.

Pathogen Resistance Assay

Bacterial growth in Arabidopsis was monitored as described with some modifications (Tornero and Dangl, 2001). Pseudomonas syringae pv tomato DC3000 was grown overnight on the Kapadnis-Baseri medium and resuspended at 108 cfu mL−1 in a solution of 10 mm MgCl2 and 0.02% Silwet L-77. Two-week-old seedlings were dip inoculated with bacteria and kept covered for 1 h. The amount of bacteria in plants was analyzed at 1 h after dipping (day 0) and 4 d after dipping (day 4). The aerial parts of three inoculated seedlings were pooled for each sample and three samples were collected for each genotype at one time point. Seedlings were ground in 1 mL of 10 mm of MgCl2 and serial dilutions of the ground tissue were used to determine the number of cfu per gram of leaf tissues.

For HR test, Pst DC3000 with avirulent genes were resuspended at 108 cfu mL−1 and infiltrated into leaves of 4-week-old Arabidopsis plants. Infiltrated leaves were monitored hourly for symptoms of cell collapse.

Hyaloparanospora parasitica Noco2 strain was propagated on the Col accession of Arabidopsis. Conidiospores were suspended in water at a concentration of 40,000 spores per mL and spray inoculated onto 2-week-old plants that were subsequently kept covered at 16°C. The number of sporangiophores formed on the first two true leaves was counted a week later. Approximately 100 leaves were counted for each genotype.

Agrobacterium-Mediated Transient Expression

Genes to be expressed are cloned into binary vectors and transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain C58C1 containing the virulence plasmid pCH32 (Rairdan and Moffett, 2006). Agrobacterium infiltrations were performed as described (Bendahmane et al., 2000) with modified inoculation concentrations as specified.

The genomic fragments of the BAP1, BAP2, and BON1 genes were expressed with the CaMV 35S promoter in the binary pGreen0229 vector (http://www.pgreen.ac.uk/). Agrobacterial cells containing BON1, BAP1, BAP2, or the empty vector were each resuspended in the infiltration buffer (10 mm MgCl2, 10 mm MES, and 150 μm Acetosyringone) at 0.5 OD600. Cells with Rx or CP were resuspended at 0.2 OD600 and combined at 1:1 to make the Rx and CP mixture. Cells containing the pDEX:Bax were resuspended at 0.5 OD600 2 h prior to infiltration. A total of 50 μm of DEX was sprayed onto Nicotiana benthamiana leaves 15 h after infiltration.

Cell Death Analysis in Plants

Autofluorescence of leaf tissues was examined as described (Adam and Somerville, 1996). Trypan blue staining was performed as described (Bowling et al., 1997). DAB was dissolved in 50 mm of Tris-acetate (pH 5.0) at a concentration of 1 mg/mL. Leaf discs or whole seedlings were punched out, placed in the DAB solution, and vacuum infiltrated till the tissues were soaked. They were then incubated at room temperature in the dark for 24 h before the tissues were cleared in boiling ethanol (95%) for 10 min.

For paraquat treatment, leaf discs from 3-week-old plants were floated on 4 μm of paraquat. They were first kept in dark for 1 h and then incubated under light for 2 to 3 d.

Cell Death Test in Yeasts

The coding regions of the BAP1 and BAP2 genes were cloned into the pAD4M vector under the control of the ADH promoter (from Dr. G. Fink). Constructs were transformed into yeast strain PJ69-4 by LiAc-mediated transformation (http://mgwww.mbi.ucla.edu/node/124). Two independent transformants of BAP1 and BAP2 were used for cell death test. Yeast cells were grown in selective liquid medium (SC-Leu) for 36 h, collected by centrifugation, washed three times with water, and resuspended in fresh medium at a concentration of 0.5 OD600. Each sample was split into two halves with one treated with H2O2 at a final concentration of 10 mm or 5 mm and the other with water as mock control. The amount of live cells at 12 h after treatment was analyzed by growing serial dilutions onto rich media.

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession number NM_130139.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Arabidopsis Bioresource Research Center for providing T-DNA insertion lines, J. Parker, J. Glazebrook, and X. Dong for Arabidopsis mutants, H. Uchimiya and G. Fink for plasmids, and P. Moffett, A. Collmer, and T. Delaney for bacterial and oomyete strains.

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (grant no. 0415597 to J.H.).

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantphysiol.org) is: Jian Hua (jh299@cornell.edu).

Open Access articles can be viewed online without a subscription.

References

- Abramovitch RB, Kim YJ, Chen S, Dickman MB, Martin GB (2003) Pseudomonas type III effector AvrPtoB induces plant disease susceptibility by inhibition of host programmed cell death. EMBO J 22 60–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adam L, Somerville SC (1996) Genetic characterization of five powdery mildew disease resistance loci in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 9 341–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axtell MJ, Staskawicz BJ (2003) Initiation of RPS2-specified disease resistance in Arabidopsis is coupled to the AvrRpt2-directed elimination of RIN4. Cell 112 369–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo C, Betsuyaku S, Peart J, Takahashi A, Noel L, Sadanandom A, Casais C, Parker J, Shirasu K (2006) Role of SGT1 in resistance protein accumulation in plant immunity. EMBO J 25 2007–2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo C, Sadanandom A, Kitagawa K, Freialdenhoven A, Shirasu K, Schulze-Lefert P (2002) The RAR1 interactor SGT1, an essential component of R gene-triggered disease resistance. Science 295 2073–2076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beers EP, McDowell JM (2001) Regulation and execution of programmed cell death in response to pathogens, stress and developmental cues. Curr Opin Plant Biol 4 561–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendahmane A, Querci M, Kanyuka K, Baulcombe DC (2000) Agrobacterium transient expression system as a tool for the isolation of disease resistance genes: application to the Rx2 locus in potato. Plant J 21 73–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowling SA, Clarke JD, Liu Y, Klessig DF, Dong X (1997) The cpr5 mutant of Arabidopsis expresses both NPR1-dependent and NPR1-independent resistance. Plant Cell 9 1573–1584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buschges R, Hollricher K, Panstruga R, Simons G, Wolter M, Frijters A, van Daelen R, van der Lee T, Diergaarde P, Groenendijk J, et al (1997) The barley Mlo gene: a novel control element of plant pathogen resistance. Cell 88 695–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm ST, Coaker G, Day B, Staskawicz BJ (2006) Host-microbe interactions: shaping the evolution of the plant immune response. Cell 124 803–814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke JD, Aarts N, Feys BJ, Dong X, Parker JE (2001) Constitutive disease resistance requires EDS1 in the Arabidopsis mutants cpr1 and cpr6 and is partially EDS1-dependent in cpr5. Plant J 26 409–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangl JL, Jones JD (2001) Plant pathogens and integrated defence responses to infection. Nature 411 826–833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devarenne TP, Ekengren SK, Pedley KF, Martin GB (2006) Adi3 is a Pdk1-interacting AGC kinase that negatively regulates plant cell death. EMBO J 25 255–265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickman MB, Park YK, Oltersdorf T, Li W, Clemente T, French R (2001) Abrogation of disease development in plants expressing animal antiapoptotic genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98 6957–6962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durrant WE, Dong X (2004) Systemic acquired resistance. Annu Rev Phytopathol 42 185–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichmann R, Dechert C, Kogel K, Huckelhoven R (2006) Transient over-expression of barley BAX Inhibitor-1 weakens oxidative defence and MLA12-mediated resistance to Blumeria graminus f.sp. hordei. Mol Plant Pathol 7 543–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields S, Song O (1989) A novel genetic system to detect protein-protein interactions. Nature 340 245–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flor HH (1971) Current status of the gene-for-gene concept. Annu Rev Phytopathol 9 275–296 [Google Scholar]

- Gilchrist DG (1998) Programmed cell death in plant disease: the purpose and promise of cellular suicide. Annu Rev Phytopathol 36 393–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazebrook J (2001) Genes controlling expression of defense responses in Arabidopsis—2001 status. Curr Opin Plant Biol 4 301–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg JT (1996) Programmed cell death: a way of life for plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93 12094–12097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg JT, Yao N (2004) The role and regulation of programmed cell death in plant-pathogen interactions. Cell Microbiol 6 201–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt BF III, Belkhadir Y, Dangl JL (2005) Antagonistic control of disease resistance protein stability in the plant immune system. Science 309 929–932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua J, Grisafi P, Cheng SH, Fink GR (2001) Plant growth homeostasis is controlled by the Arabidopsis BON1 and BAP1 genes. Genes Dev 15 2263–2272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihara-Ohori Y, Nagano M, Muto S, Uchimiya H, Kawai-Yamada M (2007) Cell death suppressor Arabidopsis bax inhibitor-1 is associated with calmodulin binding and ion homeostasis. Plant Physiol 143 650–660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson MD, Weil M, Raff MC (1997) Programmed cell death in animal development. Cell 88 347–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jambunathan N, Siani JM, McNellis TW (2001) A humidity-sensitive Arabidopsis copine mutant exhibits precocious cell death and increased disease resistance. Plant Cell 13 2225–2240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James P, Halladay J, Craig EA (1996) Genomic libraries and a host strain designed for highly efficient two-hybrid selection in yeast. Genetics 144 1425–1436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JD, Dangl JL (2006) The plant immune system. Nature 444 323–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai-Yamada M, Jin L, Yoshinaga K, Hirata A, Uchimiya H (2001) Mammalian Bax-induced plant cell death can be down-regulated by overexpression of Arabidopsis Bax Inhibitor-1 (AtBI-1). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98 12295–12300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacomme C, Santa Cruz S (1999) Bax-induced cell death in tobacco is similar to the hypersensitive response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96 7956–7961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam E (2004) Controlled cell death, plant survival and development. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5 305–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb C, Dixon RA (1997) The oxidative burst in plant disease resistance. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 48 251–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine A, Belenghi B, Damari-Weisler H, Granot D (2001) Vesicle-associated membrane protein of Arabidopsis suppresses Bax-induced apoptosis in yeast downstream of oxidative burst. J Biol Chem 276 46284–46289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little D, Darimont C, Bruessow F, Reymond P (2007) Oviposition by pierid butterflies triggers defense responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 143 784–800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorrain S, Vailleau F, Balague C, Roby D (2003) Lesion mimic mutants: keys for deciphering cell death and defense pathways in plants? Trends Plant Sci 8 263–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackey D, Belkhadir Y, Alonso JM, Ecker JR, Dangl JL (2003) Arabidopsis RIN4 is a target of the type III virulence effector AvrRpt2 and modulates RPS2-mediated resistance. Cell 112 379–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin G, Bogdanove A, Sessa G (2003) Understanding the functions of plant disease resistance proteins. Annu Rev Plant Biol 54 23–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateo A, Muhlenbock P, Rusterucci C, Chang CC, Miszalski Z, Karpinska B, Parker JE, Mullineaux PM, Karpinski S (2004) LESION SIMULATING DISEASE 1 is required for acclimation to conditions that promote excess excitation energy. Plant Physiol 136 2818–2830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers BC, Kozik A, Griego A, Kuang H, Michelmore RW (2003) Genome-wide analysis of NBS-LRR-encoding genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 15 809–834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuhara I, Malik KA, Miura M, Ohashi Y (1999) Animal cell-death suppressors Bcl-x(L) and Ced-9 inhibit cell death in tobacco plants. Curr Biol 9 775–778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler R, Shulaev V, Lam E (1995) Coordinated activation of programmed cell death and defense mechanisms in transgenic tobacco plants expressing a bacterial proton pump. Plant Cell 7 29–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina A, Volrath S, Guyer D, Maleck K, Ryals J, Ward E (1999) Inhibition of protoporphyrinogen oxidase expression in Arabidopsis causes a lesion-mimic phenotype that induces systemic acquired resistance. Plant J 17 667–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsenbein C, Przybyla D, Danon A, Landgraf F, Gobel C, Imboden A, Feussner I, Apel K (2006) The role of EDS1 (enhanced disease susceptibility) during singlet oxygen-mediated stress responses of Arabidopsis. Plant J 47 445–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa T, Pan L, Kawai-Yamada M, Yu LH, Yamamura S, Koyama T, Kitajima S, Ohme-Takagi M, Sato F, Uchimiya H (2005) Functional analysis of Arabidopsis ethylene-responsive element binding protein conferring resistance to Bax and abiotic stress-induced plant cell death. Plant Physiol 138 1436–1445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- op den Camp RG, Przybyla D, Ochsenbein C, Laloi C, Kim C, Danon A, Wagner D, Hideg E, Gobel C, Feussner I, et al (2003) Rapid induction of distinct stress responses after the release of singlet oxygen in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 15 2320–2332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan L, Kawai M, Yu LH, Kim KM, Hirata A, Umeda M, Uchimiya H (2001) The Arabidopsis thaliana ethylene-responsive element binding protein (AtEBP) can function as a dominant suppressor of Bax-induced cell death of yeast. FEBS Lett 508 375–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panstruga R (2005) Serpentine plant MLO proteins as entry portals for powdery mildew fungi. Biochem Soc Trans 33 389–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rairdan GJ, Moffett P (2006) Distinct domains in the ARC region of the potato resistance protein Rx mediate LRR binding and inhibition of activation. Plant Cell 18 2082–2093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusterucci C, Aviv DH, Holt BF III, Dangl JL, Parker JE (2001) The disease resistance signaling components EDS1 and PAD4 are essential regulators of the cell death pathway controlled by LSD1 in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 13 2211–2224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheel D (1998) Resistance response physiology and signal transduction. Curr Opin Plant Biol 1 305–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze-Lefert P (2004) Plant immunity: the origami of receptor activation. Curr Biol 14 R22–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirasu K, Schulze-Lefert P (2000) Regulators of cell death in disease resistance. Plant Mol Biol 44 371–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes TL, Kunkel BN, Richards EJ (2002) Epigenetic variation in Arabidopsis disease resistance. Genes Dev 16 171–182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tornero P, Dangl JL (2001) A high-throughput method for quantifying growth of phytopathogenic bacteria in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 28 475–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres MA, Jones JD, Dangl JL (2005) Pathogen-induced, NADPH oxidase-derived reactive oxygen intermediates suppress spread of cell death in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat Genet 37 1130–1134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang EW, Bowler C, Herouart D, Van Camp W, Villarroel R, Genetello C, Van Montagu M, Inze D (1991) Differential regulation of superoxide dismutases in plants exposed to environmental stress. Plant Cell 3 783–792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Breusegem F, Dat JF (2006) Reactive oxygen species in plant cell death. Plant Physiol 141 384–390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe N, Lam E (2006) Arabidopsis Bax inhibitor-1 functions as an attenuator of biotic and abiotic types of cell death. Plant J 45 884–894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiermer M, Feys BJ, Parker JE (2005) Plant immunity: the EDS1 regulatory node. Curr Opin Plant Biol 8 383–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P, Rogers SJ, Roossinck MJ (2004) Expression of antiapoptotic genes bcl-xL and ced-9 in tomato enhances tolerance to viral-induced necrosis and abiotic stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101 15805–15810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Li Y, Hua J (2006. a) The C2 domain protein BAP1 negatively regulates defense responses in Arabidopsis. Plant J 48 238–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S, Hua J (2004) A haplotype-specific Resistance gene regulated by BONZAI1 mediates temperature-dependent growth control in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 16 1060–1071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S, Yang H, Grisafi P, Sanchatjate S, Fink GR, Sun Q, Hua J (2006. b) The BON/CPN gene family represses cell death and promotes cell growth in Arabidopsis. Plant J 45 166–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Goritschnig S, Dong X, Li X (2003) A gain-of-function mutation in a plant disease resistance gene leads to constitutive activation of downstream signal transduction pathways in suppressor of npr1-1, constitutive 1. Plant Cell 15 2636–2646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]