Abstract

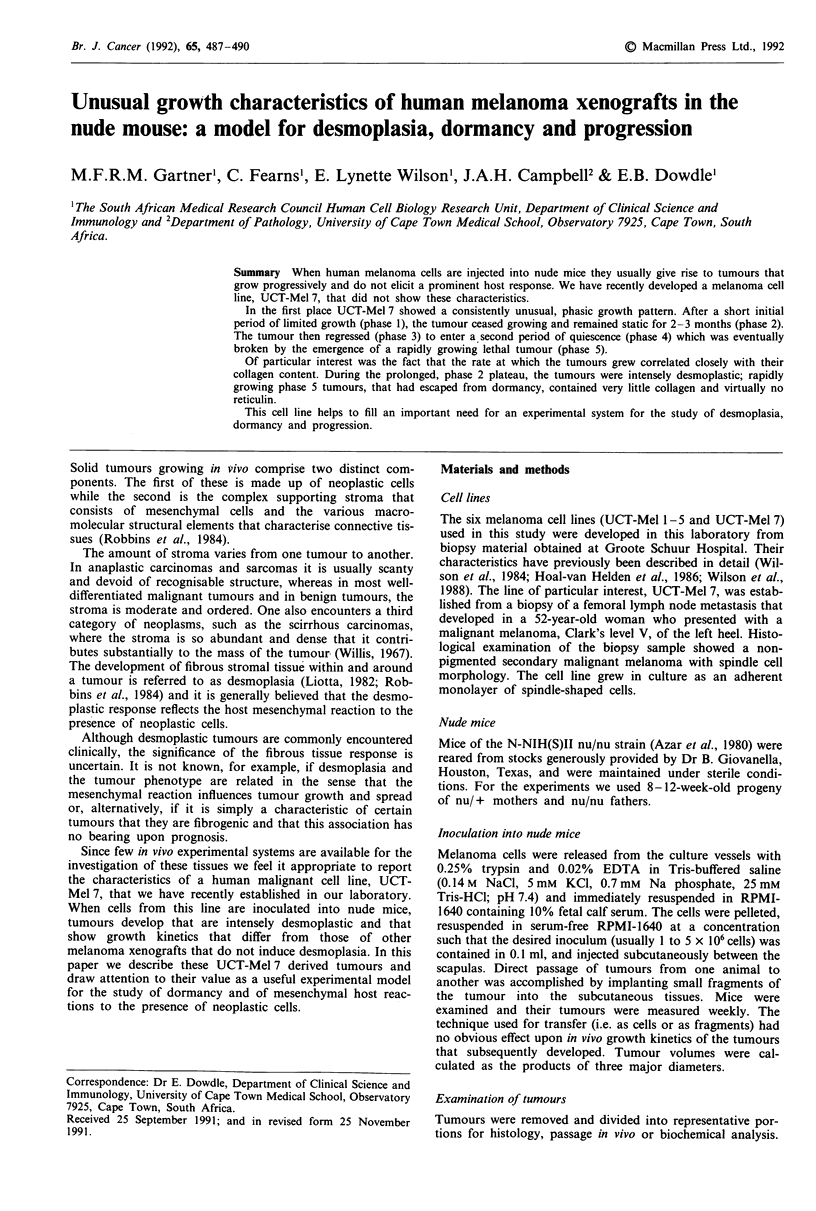

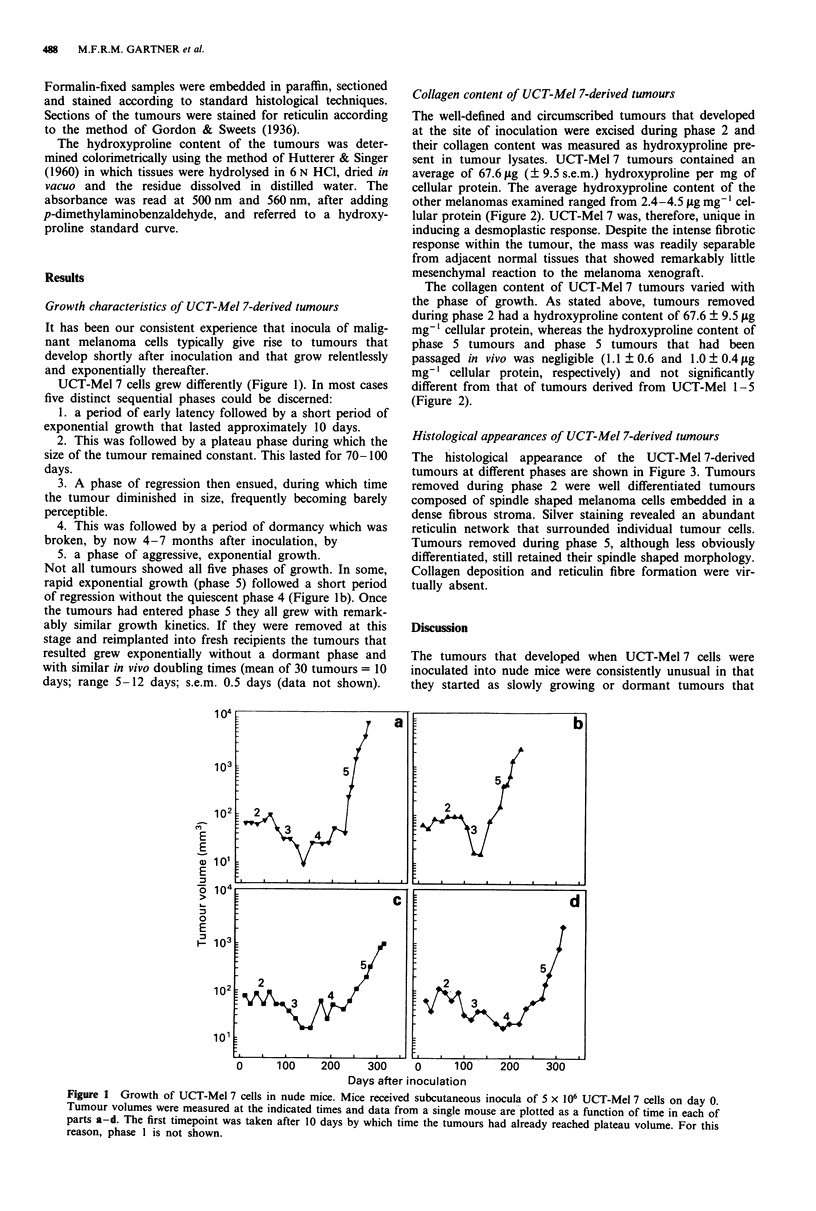

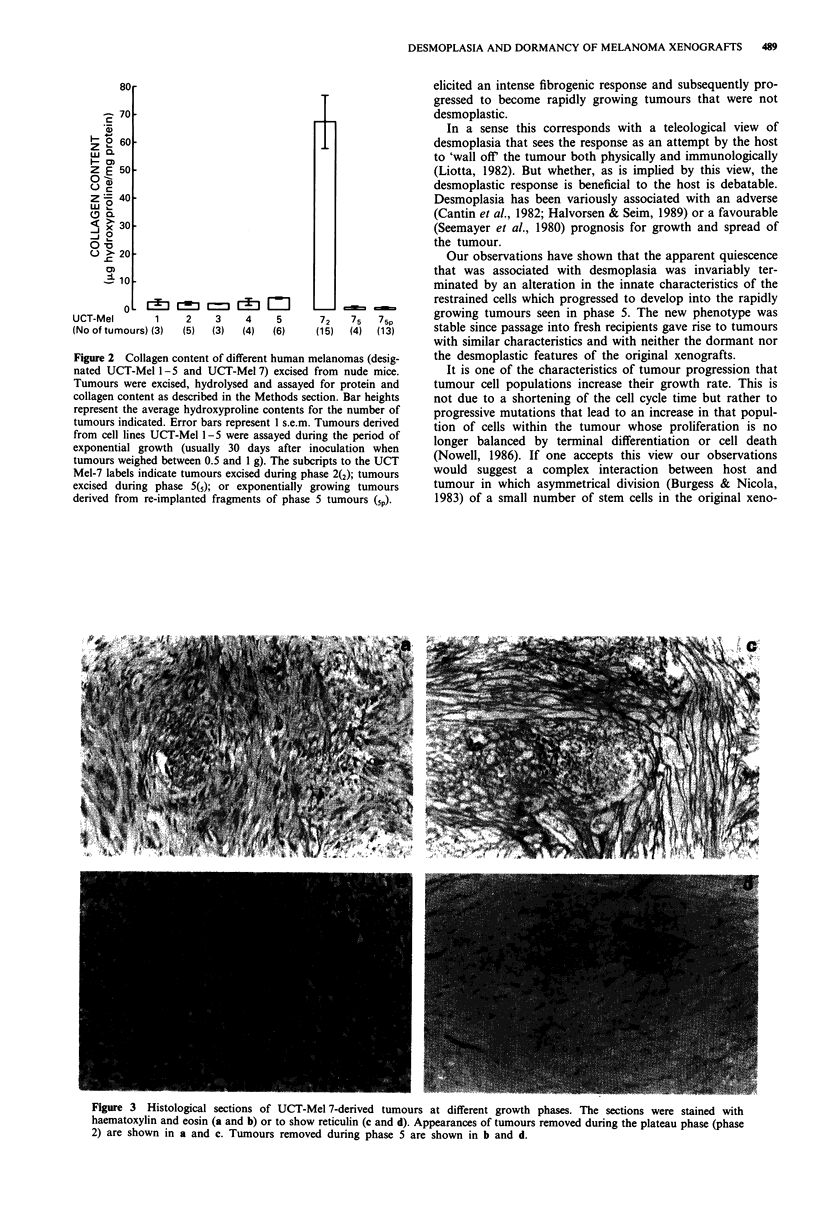

When human melanoma cells are injected into nude mice they usually give rise to tumours that grow progressively and do not elicit a prominent host response. We have recently developed a melanoma cell line, UCT-Mel 7, that did not show these characteristics. In the first place UCT-Mel 7 showed a consistently unusual, phasic growth pattern. After a short initial period of limited growth (phase 1), the tumour ceased growing and remained static for 2-3 months (phase 2). The tumour then regressed (phase 3) to enter a second period of quiescence (phase 4) which was eventually broken by the emergence of a rapidly growing lethal tumour (phase 5). Of particular interest was the fact that the rate at which the tumours grew correlated closely with their collagen content. During the prolonged, phase 2 plateau, the tumours were intensely desmoplastic; rapidly growing phase 5 tumours, that had escaped from dormancy, contained very little collagen and virtually no reticulin. This cell line helps to fill an important need for an experimental system for the study of desmoplasia, dormancy and progression.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Azar H. A., Hansen C. T., Costa J. N:NIH(S)-nu/nu mice with combined immunodeficiency: a new model for human tumor heterotransplantation. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1980 Aug;65(2):421–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsky S. H., Gopalakrishna R. Increased invasion and spontaneous metastasis of BL6 melanoma with inhibition of the desmoplastic response in C57 BL/6 mice. Cancer Res. 1987 Mar 15;47(6):1663–1667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker D., Meier C. B., Herlyn M. Proliferation of human malignant melanomas is inhibited by antisense oligodeoxynucleotides targeted against basic fibroblast growth factor. EMBO J. 1989 Dec 1;8(12):3685–3691. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08543.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantin R., Al-Jabi M., McCaughey W. T. Desmoplastic diffuse mesothelioma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1982 Apr;6(3):215–222. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198204000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon H., Sweets H. H. A Simple Method for the Silver Impregnation of Reticulum. Am J Pathol. 1936 Jul;12(4):545–552.1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gospodarowicz D. Fibroblast growth factor: structural and biological properties. Int J Rad Appl Instrum B. 1987;14(4):421–434. doi: 10.1016/0883-2897(87)90019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halaban R., Kwon B. S., Ghosh S., Delli Bovi P., Baird A. bFGF as an autocrine growth factor for human melanomas. Oncogene Res. 1988 Sep;3(2):177–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halvorsen T. B., Seim E. Association between invasiveness, inflammatory reaction, desmoplasia and survival in colorectal cancer. J Clin Pathol. 1989 Feb;42(2):162–166. doi: 10.1136/jcp.42.2.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoal-Van Helden E. G., Wilson E. L., Dowdle E. B. Characterization of seven human melanoma cell lines: melanogenesis and secretion of plasminogen activators. Br J Cancer. 1986 Aug;54(2):287–295. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1986.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignotz R. A., Endo T., Massagué J. Regulation of fibronectin and type I collagen mRNA levels by transforming growth factor-beta. J Biol Chem. 1987 May 15;262(14):6443–6446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labat-Robert J., Bihari-Varga M., Robert L. Extracellular matrix. FEBS Lett. 1990 Aug 1;268(2):386–393. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81291-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liotta L. A. Tumor extracellular matrix. Lab Invest. 1982 Aug;47(2):112–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowell P. C. Mechanisms of tumor progression. Cancer Res. 1986 May;46(5):2203–2207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghow R., Postlethwaite A. E., Keski-Oja J., Moses H. L., Kang A. H. Transforming growth factor-beta increases steady state levels of type I procollagen and fibronectin messenger RNAs posttranscriptionally in cultured human dermal fibroblasts. J Clin Invest. 1987 Apr;79(4):1285–1288. doi: 10.1172/JCI112950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts R., Gallagher J., Spooncer E., Allen T. D., Bloomfield F., Dexter T. M. Heparan sulphate bound growth factors: a mechanism for stromal cell mediated haemopoiesis. Nature. 1988 Mar 24;332(6162):376–378. doi: 10.1038/332376a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saksela O., Moscatelli D., Sommer A., Rifkin D. B. Endothelial cell-derived heparan sulfate binds basic fibroblast growth factor and protects it from proteolytic degradation. J Cell Biol. 1988 Aug;107(2):743–751. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.2.743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seemayer T. A., Lagacé R., Schürch W. On the pathogenesis of sclerosis and nodularity in nodular sclerosing Hodgkin's disease. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histol. 1980;385(3):283–291. doi: 10.1007/BF00432538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlodavsky I., Folkman J., Sullivan R., Fridman R., Ishai-Michaeli R., Sasse J., Klagsbrun M. Endothelial cell-derived basic fibroblast growth factor: synthesis and deposition into subendothelial extracellular matrix. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987 Apr;84(8):2292–2296. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.8.2292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson E. L., Gartner M. F., Campbell J. A., Dowdle E. B. Metastasis of a human melanoma cell line in the nude mouse. Int J Cancer. 1988 Jan 15;41(1):83–86. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910410116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]