Abstract

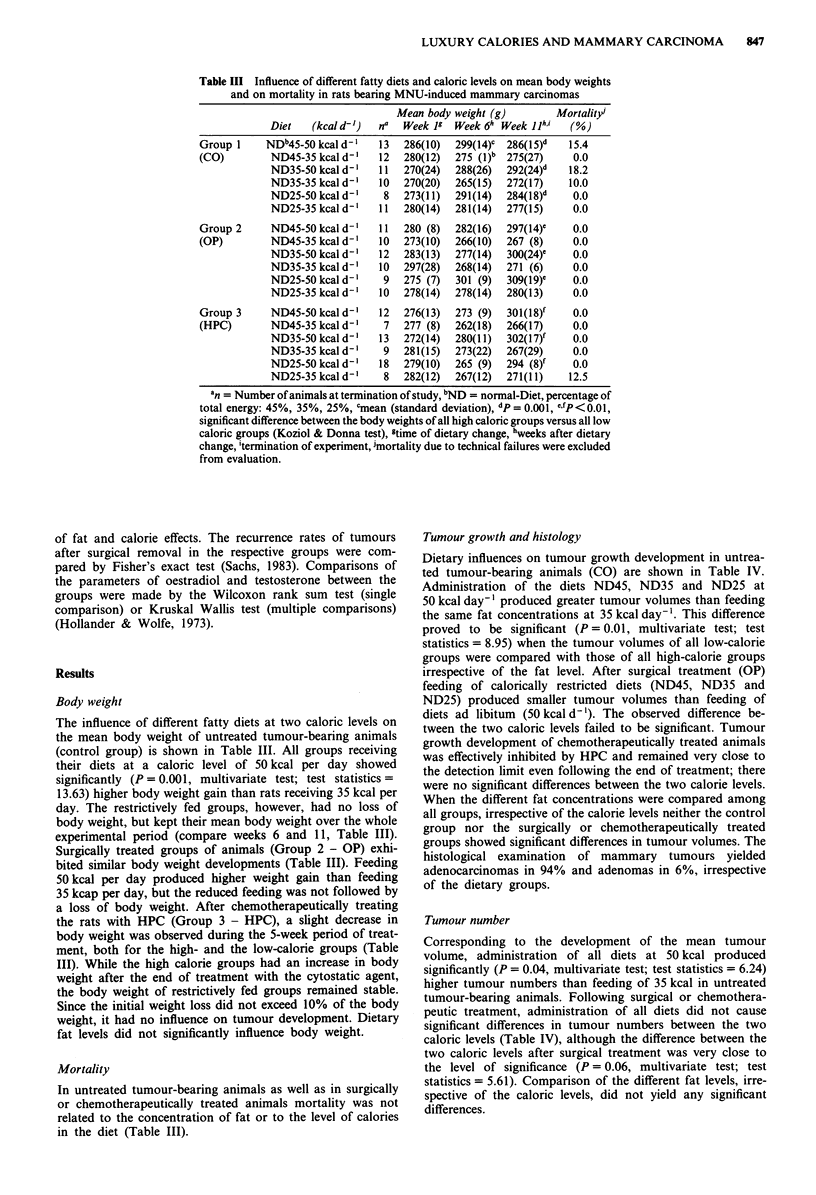

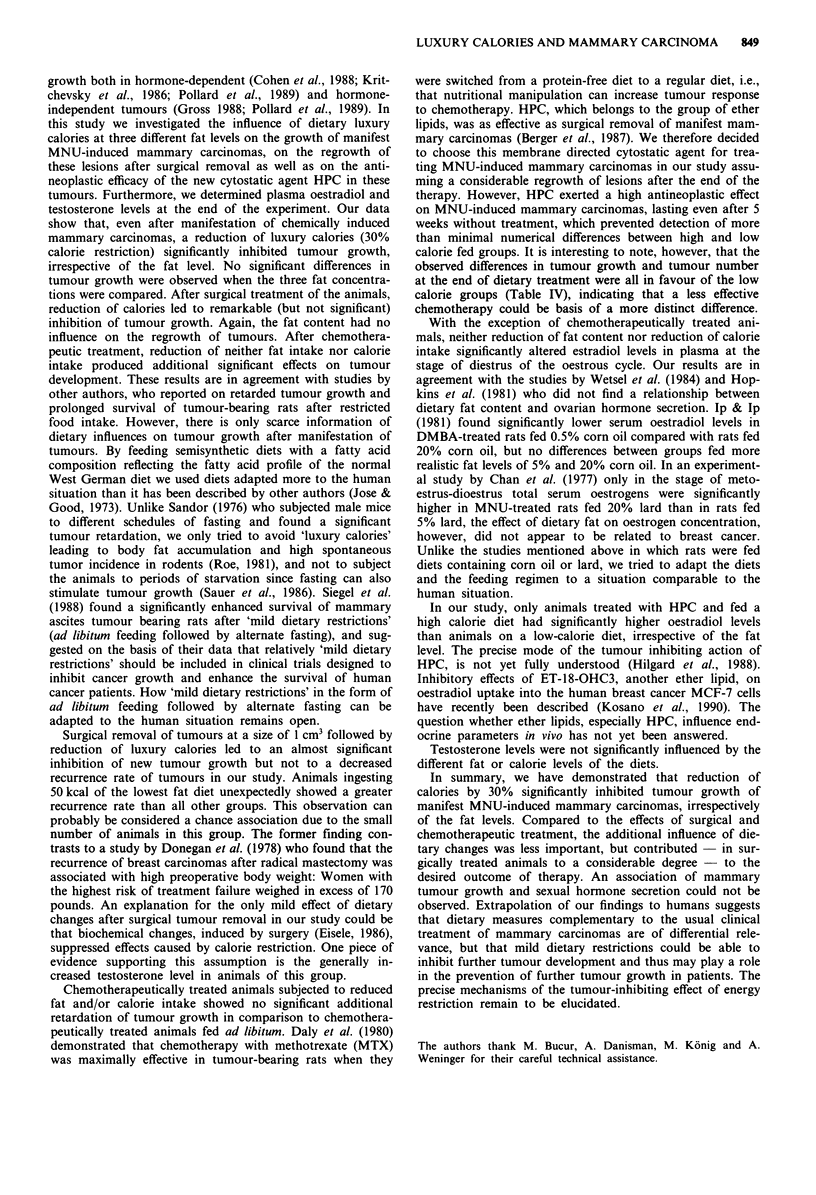

The aim of this study was to investigate the influence of dietary calorie intake at three different fat levels on (a) the growth of established methylnitrosourea (MNU)-induced mammary carcinoma, (b) the reappearance of mammary carcinomas after surgical removal, and (c) the growth of manifest lesions in animals treated with the cytostatic agent hexadecylphosphocholine (HPC). A reduction of calories by 30% significantly inhibited tumour growth of manifest mammary carcinomas in rats, without having a negative influence on body weight gain. After chemotherapeutic treatment no significant dietary influence was observed besides the high antineoplastic efficacy of HPC, but when feeding calorically restricted diets to surgically treated animals the number of reappearing tumours was considerably smaller (P = 0.06) than after feeding the diets ad libitum. The fat content of the diets did not influence the growth of manifest mammary carcinomas. No significant dietary effects were exerted on oestradiol or testosterone levels in untreated tumour bearing animals. An elevation of oestradiol levels was observed when animals were subjected to HPC and fed a high calorie diet. An elevation of testosterone levels was assessed after surgical treatment of the rats, irrespective of fat content and calorie level. Our results suggest that a reduction of calories can inhibit growth of manifest mammary carcinomas and has impeding effects on tumour development after surgical removal. After effective chemotherapeutic treatment the additional influence of dietary changes was of less relevance. Furthermore, our data do not establish any association between growth inhibition of mammary tumours, caused by the mild caloric restriction, and altered oestradiol or testosterone production.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Aylsworth C. F., Sylvester P. W., Leung F. C., Meites J. Inhibition of mammary tumor growth by dexamethasone in rats in the presence of high serum prolactin levels. Cancer Res. 1980 Jun;40(6):1863–1866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aylsworth C. F., Van Vugt D. A., Sylvester P. W., Meites J. Role of estrogen and prolactin in stimulation of carcinogen-induced mammary tumor development by a high-fat diet. Cancer Res. 1984 Jul;44(7):2835–2840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger M. R., Muschiol C., Schmähl D., Eibl H. J. New cytostatics with experimentally different toxic profiles. Cancer Treat Rev. 1987 Dec;14(3-4):307–317. doi: 10.1016/0305-7372(87)90023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beth M., Berger M. R., Aksoy M., Schmähl D. Comparison between the effects of dietary fat level and of calorie intake on methylnitrosourea-induced mammary carcinogenesis in female SD rats. Int J Cancer. 1987 Jun 15;39(6):737–744. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910390614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll K. K., Khor H. T. Effects of level and type of dietary fat on incidence of mammary tumors induced in female Sprague-Dawley rats by 7,12-dimethylbenz()anthracene. Lipids. 1971 Jun;6(6):415–420. doi: 10.1007/BF02531379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan P. C., Head J. F., Cohen L. A., Wynder E. L. Influence of dietary fat on the induction of mammary tumors by N-nitrosomethylurea: associated hormone changes and differences between Sprague-Dawley and F344 rats. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1977 Oct;59(4):1279–1283. doi: 10.1093/jnci/59.4.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinton S. K., Alster J. M., Imrey P. B., Simon J., Visek W. J. The combined effects of dietary protein and fat intake during the promotion phase of 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene-induced breast cancer in rats. J Nutr. 1988 Dec;118(12):1577–1585. doi: 10.1093/jn/118.12.1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen L. A., Choi K. W., Wang C. X. Influence of dietary fat, caloric restriction, and voluntary exercise on N-nitrosomethylurea-induced mammary tumorigenesis in rats. Cancer Res. 1988 Aug 1;48(15):4276–4283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen L. A. Mechanisms by which dietary fat may stimulate mammary carcinogenesis in experimental animals. Cancer Res. 1981 Sep;41(9 Pt 2):3808–3810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly J. M., Reynolds H. M., Rowlands B. J., Dudrick S. J., Copeland E. M., 3rd Tumor growth in experimental animals: nutritional manipulation and chemotherapeutic response in the rat. Ann Surg. 1980 Mar;191(3):316–322. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198003000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donegan W. L., Hartz A. J., Rimm A. A. The association of body weight with recurrent cancer of the breast. Cancer. 1978 Apr;41(4):1590–1594. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197804)41:4<1590::aid-cncr2820410449>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelman R. W., Day N. K., Chen R. F., Tomita Y., Bauer-Sardiña I., Dao M. L., Good R. A. Calorie consumption level influences development of C3H/Ou breast adenocarcinoma with indifference to calorie source. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1990 Jan;193(1):23–30. doi: 10.3181/00379727-193-42984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman J. M., Hilf R. A role of estrogens and insulin binding in the dietary lipid alteration of R3230AC mammary carcinoma growth in rats. Cancer Res. 1985 May;45(5):1964–1972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham S., Marshall J., Mettlin C., Rzepka T., Nemoto T., Byers T. Diet in the epidemiology of breast cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 1982 Jul;116(1):68–75. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross L. Inhibition of the development of tumors or leukemia in mice and rats after reduction of food intake. Possible implications for humans. Cancer. 1988 Oct 15;62(8):1463–1465. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19881015)62:8<1463::aid-cncr2820620802>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgard P., Stekar J., Voegeli R., Engel J., Schumacher W., Eibl H., Unger C., Berger M. R. Characterization of the antitumor activity of hexadecylphosphocholine (D 18506). Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1988 Sep;24(9):1457–1461. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(88)90336-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirayama T. Epidemiology of breast cancer with special reference to the role of diet. Prev Med. 1978 Jun;7(2):173–195. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(78)90244-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirohata T., Nomura A. M., Hankin J. H., Kolonel L. N., Lee J. An epidemiologic study on the association between diet and breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1987 Apr;78(4):595–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hislop T. G., Coldman A. J., Elwood J. M., Brauer G., Kan L. Childhood and recent eating patterns and risk of breast cancer. Cancer Detect Prev. 1986;9(1-2):47–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins G. J., Kennedy T. G., Carroll K. K. Polyunsaturated fatty acids as promoters of mammary carcinogenesis induced in Sprague-Dawley rats by 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1981 Mar;66(3):517–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe G. R., Hirohata T., Hislop T. G., Iscovich J. M., Yuan J. M., Katsouyanni K., Lubin F., Marubini E., Modan B., Rohan T. Dietary factors and risk of breast cancer: combined analysis of 12 case-control studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1990 Apr 4;82(7):561–569. doi: 10.1093/jnci/82.7.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulka B. S. Dietary fat and breast cancer: case-control and cohort studies. Prev Med. 1989 Mar;18(2):180–193. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(89)90065-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hursting S. D., Thornquist M., Henderson M. M. Types of dietary fat and the incidence of cancer at five sites. Prev Med. 1990 May;19(3):242–253. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(90)90025-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ip C., Ip M. M. Inhibition of mammary tumorigenesis by a reduction of fat intake after carcinogen treatment in young versus adult rats. Cancer Lett. 1980 Nov;11(1):35–42. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(80)90126-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ip C., Ip M. M. Serum estrogens and estrogen responsiveness in 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene-induced mammary tumors as influenced by dietary fat. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1981 Feb;66(2):291–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ip C., Yip P., Bernardis L. L. Role of prolactin in the promotion of dimethylbenz[a]anthracene-induced mammary tumors by dietary fat. Cancer Res. 1980 Feb;40(2):374–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D. Y., Schatzkin A., Green S. B., Block G., Brinton L. A., Ziegler R. G., Hoover R., Taylor P. R. Dietary fat and breast cancer in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey I Epidemiologic Follow-up Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1987 Sep;79(3):465–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jose D. G., Good R. A. Quantitative effects of nutritional protein and calorie deficiency upon immune responses to tumors in mice. Cancer Res. 1973 Apr;33(4):807–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klurfeld D. M., Welch C. B., Davis M. J., Kritchevsky D. Determination of degree of energy restriction necessary to reduce DMBA-induced mammary tumorigenesis in rats during the promotion phase. J Nutr. 1989 Feb;119(2):286–291. doi: 10.1093/jn/119.2.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosano H., Yasutomo Y., Kugai N., Nagata N., Inagaki H., Tanaka S., Takatani O. Inhibition of estradiol uptake and transforming growth factor alpha secretion in human breast cancer cell line MCF-7 by an alkyl-lysophospholipid. Cancer Res. 1990 Jun 1;50(11):3172–3175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koziol J. A., Maxwell D. A., Fukushima M., Colmerauer M. E., Pilch Y. H. A distribution-free test for tumor-growth curve analyses with application to an animal tumor immunotherapy experiment. Biometrics. 1981 Jun;37(2):383–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kritchevsky D., Weber M. M., Buck C. L., Klurfeld D. M. Calories, fat and cancer. Lipids. 1986 Apr;21(4):272–274. doi: 10.1007/BF02536411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kritchevsky D., Welch C. B., Klurfeld D. M. Response of mammary tumors to caloric restriction for different time periods during the promotion phase. Nutr Cancer. 1989;12(3):259–269. doi: 10.1080/01635588909514025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumaki T., Noguchi M. Effects of high dietary fat on the total DNA and receptor contents in rats with 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene-induced mammary carcinoma. Oncology. 1990;47(4):352–358. doi: 10.1159/000226847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasekan J. B., Clayton M. K., Gendron-Fitzpatrick A., Ney D. M. Dietary olive and safflower oils in promotion of DMBA-induced mammary tumorigenesis in rats. Nutr Cancer. 1990;13(3):153–163. doi: 10.1080/01635589009514056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubin F., Wax Y., Modan B. Role of fat, animal protein, and dietary fiber in breast cancer etiology: a case-control study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1986 Sep;77(3):605–612. doi: 10.1093/jnci/77.3.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills P. K., Annegers J. F., Phillips R. L. Animal product consumption and subsequent fatal breast cancer risk among Seventh-day Adventists. Am J Epidemiol. 1988 Mar;127(3):440–453. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y., Kodama M., Kodama T. Relation between adrenal function and 7, 12-dimethylbenz[a]-anthracene-induced mammary cancer of the rat. Gan. 1981 Oct;72(5):679–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips R. L., Snowdon D. A. Association of meat and coffee use with cancers of the large bowel, breast, and prostate among Seventh-Day Adventists: preliminary results. Cancer Res. 1983 May;43(5 Suppl):2403s–2408s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard M., Luckert P. H., Snyder D. Prevention of prostate cancer and liver tumors in L-W rats by moderate dietary restriction. Cancer. 1989 Aug 1;64(3):686–690. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890801)64:3<686::aid-cncr2820640320>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe F. J. Are nutritionists worried about the epidemic of tumours in laboratory animals? Proc Nutr Soc. 1981 Jan;40(1):57–65. doi: 10.1079/pns19810010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosén M., Nyström L., Wall S. Diet and cancer mortality in the counties of Sweden. Am J Epidemiol. 1988 Jan;127(1):42–49. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandor R. S. Effects of fasting on growth and glycolysis of the Ehrlich ascites tumor. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1976 Feb;56(2):427–428. doi: 10.1093/jnci/56.2.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer L. A., Nagel W. O., Dauchy R. T., Miceli L. A., Austin J. E. Stimulation of tumor growth in adult rats in vivo during an acute fast. Cancer Res. 1986 Jul;46(7):3469–3475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatzkin A., Piantadosi S., Miccozzi M., Bartee D. Alcohol consumption and breast cancer: a cross-national correlation study. Int J Epidemiol. 1989 Mar;18(1):28–31. doi: 10.1093/ije/18.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao R. P., Dao M. L., Day N. K., Good R. A. Dietary manipulation of mammary tumor development in adult C3H/Bi mice. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1990 Apr;193(4):313–317. doi: 10.3181/00379727-193-43041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel I., Liu T. L., Nepomuceno N., Gleicher N. Effects of short-term dietary restriction on survival of mammary ascites tumor-bearing rats. Cancer Invest. 1988;6(6):677–680. doi: 10.3109/07357908809078034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundram K., Khor H. T., Ong A. S., Pathmanathan R. Effect of dietary palm oils on mammary carcinogenesis in female rats induced by 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene. Cancer Res. 1989 Mar 15;49(6):1447–1451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van't Veer P., Kok F. J., Brants H. A., Ockhuizen T., Sturmans F., Hermus R. J. Dietary fat and the risk of breast cancer. Int J Epidemiol. 1990 Mar;19(1):12–18. doi: 10.1093/ije/19.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsch C. W. Enhancement of mammary tumorigenesis by dietary fat: review of potential mechanisms. Am J Clin Nutr. 1987 Jan;45(1 Suppl):192–202. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/45.1.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsch C. W., House J. L., Herr B. L., Eliasberg S. J., Welsch M. A. Enhancement of mammary carcinogenesis by high levels of dietary fat: a phenomenon dependent on ad libitum feeding. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1990 Oct 17;82(20):1615–1620. doi: 10.1093/jnci/82.20.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetsel W. C., Rogers A. E., Rutledge A., Leavitt W. W. Absence of an effect of dietary corn oil content on plasma prolactin, progesterone, and 17 beta-estradiol in female Sprague-Dawley rats. Cancer Res. 1984 Apr;44(4):1420–1425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willett W. C., Stampfer M. J., Colditz G. A., Rosner B. A., Hennekens C. H., Speizer F. E. Dietary fat and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1987 Jan 1;316(1):22–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198701013160105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams C. M., Dickerson J. W. Dietary fat, hormones and breast cancer: the cell membrane as a possible site of interaction of these two risk factors. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1987 Apr;13(2):89–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida H., Fukunishi R., Kato Y., Matsumoto K. Progesterone-stimulated growth of mammary carcinomas induced by 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene in neonatally androgenized rats. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1980 Oct;65(4):823–828. doi: 10.1093/jnci/65.4.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]