Abstract

Objective

Children who are physically maltreated are at risk of a range of adverse outcomes in childhood and adulthood, but some children who are maltreated manage to function well despite their history of adversity. Which individual, family, and neighborhood characteristics distinguish resilient from non-resilient maltreated children? Do children’s individual strengths promote resilience even when children are exposed to multiple family and neighborhood stressors (cumulative stressors model)?

Methods

Data were from the Environmental Risk Longitudinal Study which describes a nationally-representative sample of 1,116 twin pairs and their families. Families were home-visited when the twins were 5 and 7 years old, and teachers provided information about children’s behavior at school. Interviewers rated the likelihood that children had been maltreated based on mothers’ reports of harm to the child and child welfare involvement with the family. Results: Resilient children were those who engaged in normative levels of antisocial behavior despite having been maltreated. Boys (but not girls) who had above-average intelligence and whose parents had relatively few symptoms of antisocial personality were more likely to be resilient versus non-resilient to maltreatment. Children whose parents had substance use problems and who lived in relatively high crime neighborhoods that were low on social cohesion and informal social control were less likely to be resilient versus non-resilient to maltreatment. Consistent with a cumulative stressors model of children’s adaptation, individual strengths distinguished resilient from non-resilient children under conditions of low, but not high, family and neighborhood stress.

Conclusion

These findings suggest that for children residing in multi-problem families, personal resources may not be sufficient to promote their adaptive functioning.

Keywords: Resilient maltreated children, Non-resilient maltreated children, Cumulative stressors model

Introduction

Child maltreatment includes physical, sexual, or emotional abuse and neglect and constitutes a potent stressor for children. An estimated 906,000 children in the United States were victims of abuse or neglect in 2003 (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2005) and incidence rates of maltreatment have been increasing steadily since the 1980s (Sedlak & Broadhurst, 1996). Children exposed to one form of family violence often experience other forms; neglect is the most common (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2005). A number of well-designed, prospective longitudinal studies have shown that children who are maltreated are at risk of a range of problems in childhood, adolescence and adulthood, including aggression, delinquency, and violent crime, depression, anxiety, and substance use problems, peer problems, and school failure (Cicchetti & Manly, 2001; Horwitz, Widom, McLaughlin, & White, 2001; Lansford et al., 2002; Widom & Maxfield, 2001). Thus, maltreatment is a significant public health concern and efforts should be focused not only on prevention, but on ensuring that children who have been maltreated have the best possible outcomes.

Although children who are maltreated are at risk of problems across multiple domains, not all children who are maltreated experience these difficulties. These resilient children achieve positive developmental outcomes despite the significant adversities they have faced (Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, 2000; Masten & Coatsworth, 1995). Even studies that employ stringent definitions of resilience that require children to manifest competence across multiple domains and over time find that 12–22% of children or adults who were abused as children are functioning well despite their history of maltreatment (e.g., Cicchetti, Rogosch, Lynch, & Holt, 1993; Cicchetti & Rogosch, 1997; Kaufman, Cook, Arny, Jones, & Pittinsky, 1994; McGloin & Widom, 2001). More commonly, however, children who have faced significant adversity function well in some domains, but not others and show fluctuations in functioning over time (Luthar et al., 2000).

Although definitions of resilience vary, a consensus view is emerging that resilient children are those who master normative developmental tasks despite their experiences of significant adversity (Luthar et al., 2000; Masten & Coatsworth, 1998). This definition does not require that youth excel; rather, it requires that youth function at least as well as the average child who has not been exposed to adversity. In middle childhood---the focus of the current investigation---stage-salient tasks include the ability to function well in the school environment, interact appropriately with peers, and regulate behavior (Luthar et al., 2000)

Several prospective, longitudinal studies have attempted to identify factors that promote resilience, or successful adaptation, among children who have been maltreated. Based on some of the early, seminal work on resilience (e.g., Garmezy, 1985; Werner & Smith, 1992), these studies have identified factors at the level of the child, the family, and the child’s broader social network that buffer children from the effects of maltreatment. Researchers have found that children who are resilient to maltreatment tend to be characterized by high ego-control and ego-resiliency, high self-esteem and above-average intelligence, and tend to attribute successes to their own efforts (Cicchetti et al., 1993; Feiring, Taska, & Lewis, 2002; Herrenkohl, Herrenkohl, & Egolf, 1994; Moran & Eckenrode, 1992). Having been the victim of maltreatment may influence the likelihood that children possess some of these characteristics. For example, Moran and Eckenrode (1992) showed that individuals who had experienced chronic maltreatment were less likely to possess the personal resources that protected them against depression. More recently, studies have shown that some genotypes and some profiles of physiological stress reactivity confer protection against the adverse effects of maltreatment (Caspi et al., 2002; Foley et al., 2004; Hart, Gunnar, & Cicchetti, 1996; Heim, Newport, Bonsall, Miller, & Nemeroff, 2001; Jaffee et al., 2005). Other studies have shown that females are relatively more resilient to maltreatment than males (McGloin & Widom, 2001), though it is not clear whether the factors that promote resilience to maltreatment differ for boys versus girls.

Children’s relationships with family members and other members of their social network have also been found to promote resilience to maltreatment. Maltreated children who reported being relatively more self-reliant within their families and who were able to develop close relationships with other adults scored higher on a composite measure of resilience (Cicchetti & Rogosch, 1997). Positive family changes (e.g., intervention, paternal visitation rights terminated) and, in some instances, removal to foster care have also been associated with improved functioning in isolated domains (Davidson-Arad, Englechin-Segal, & Wozner, 2003; Egeland, Carlson, & Sroufe, 1993; Olivan, 2003). With respect to children’s broader social networks, those who experience a structured school environment or who form supportive relationships with teachers or other adults in their communities tend to have better outcomes.

Children who are maltreated tend to grow up in multi-problem families characterized by poverty, exposure to inter-parental violence, parent psychopathology, criminality, drug and alcohol problems, and dangerous neighborhood conditions (Appel & Holden, 1998; Edleson, 1999; Gelles, 1992; Jaffee, 2005; Lynch & Cicchetti, 1998; Sedlak & Broadhurst, 1996). Studies have shown that maltreatment increases children’s risk of adverse outcomes independent of these correlated stressors (Cicchetti & Toth, 1995; Widom, 1991). This highlights the need to study children’s resilience in context. A transactional approach to the study of resilience would propose that neither children’s individual strengths nor the environmental context will predict who is resilient to maltreatment (Sameroff & Chandler, 1975). Rather, the fit between the child and the environment is the best predictor of children’s psychological well-being. For example, resilience to maltreatment may depend on the total number of stressors that children face. A cumulative stressors model proposes that under conditions of severe stress, positive functioning may not be possible, even for those children who possess considerable individual strengths (Repetti, Taylor, & Seeman, 2002; Rutter, 1979; Seifer, Sameroff, Baldwin, & Baldwin, 1992). For example, Sameroff and colleagues (1998) showed that personal protective factors appeared to have no effect on children’s competence when children were exposed to high numbers of environmental risk factors.

The current study used a person-centered approach to define resilience. Resilient children were those who had (1) been physically maltreated before the age of 5 years and (2) whose antisocial behavior problems as reported by teachers fell within the normal range for similarly-aged (and same-sexed) children. We relied on teachers’ reports of children’s antisocial behavior for two reasons. First, our definition of resilience was intended to reflect normative, developmentally-appropriate behavior for 5–7 year old children. Because teachers, unlike most parents, interact with large numbers of children on a daily basis, they are well-placed to judge whether a given child’s behavior is normative in comparison to the behavior of other children. Second, because many of the children were maltreated by their parents, parents’ reports of their children’s behavior may have been biased. We focused on children’s lack of antisocial behavior problems as a marker for resilience because children who are maltreated are at risk of aggressive and delinquent behaviors (Widom, 1989), and early-emerging antisocial behavior problems predict adverse outcomes across multiple domains, including peer relationships, academic achievement, and physical health (Jaffee, Belsky, Harrington, Caspi, & Moffitt, in press; Moffitt, Caspi, Harrington, & Milne, 2002).

Although the extant literature has identified multiple characteristics that are associated with resilience to maltreatment, the current study makes two contributions. First, we identify individual, family, and neighborhood characteristics that predict stable, positive adaptation over a 2-year period. Most previous studies have identified factors that promote resilience at a single point in time. Given that many children who are resilient at one point in time are not considered resilient at a later point in time (Jaffee, 2006; Kaufman et al., 1994), it is important to identify factors that are associated with persistently positive functioning. Second, unlike other studies, we identify the interplay among risk and protective factors. Characteristics at one level of the child’s ecology that promote resilience are likely to interact with risk or protective factors at other levels of the child’s ecology, but most studies of children’s resilience have not tested these interactions. By studying children’s functioning in family and neighborhood context, we test whether previously identified “main effects” of protective factors such as IQ or temperament are moderated by the child’s broader social context. This approach has the potential to inform intervention efforts by identifying the conditions under which resilience is most likely to be achieved.

The current paper had three goals. First, we developed a definition of resilience that encompassed positive adaptation over time and across informants (i.e., the teacher who reported on the child’s behavior when the child was 5 years old was different from the teacher who reported on the child’s behavior 2 years later). In order to validate this measure we tested whether children who were defined as resilient according to these criteria were also functioning successfully in other domains.

Second, we tested whether individual, family, and neighborhood characteristics would distinguish resilient from non-resilient maltreated children and tested whether the characteristics that were associated with resilience differed for girls and boys. This model presumes that certain individual, family, or neighborhood characteristics will have “protective-stabilizing” effects on children’s functioning (Luthar, 1993; Luthar et al., 2000). That is, children who have the attribute (e.g., high intelligence) and who were maltreated will be behaviorally indistinguishable from children who have the attribute and were not maltreated. It is not known whether the resilience process operates differently for maltreated boys and girls, and we are not aware of theory that would allow us to make a priori hypotheses about sex differences. Nonetheless, to be thorough, we tested for sex differences in the associations examined here.

Third, because very few studies have explored how individual and family or extra-familial factors combine to distinguish resilient from non-resilient children, we tested the hypothesis that children’s strengths would predict resilience to maltreatment only when children were exposed to relatively few family and neighborhood stressors. Thus, our analyses made two key comparisons. Comparing resilient to non-resilient children allowed us to test whether individual, family, or neighborhood factors distinguished resilient from non-resilient children. Comparing resilient to non-maltreated children allowed us test whether maltreated children were doing as well as non-maltreated children simply because both groups were exposed to relatively few family or neighborhood stressors.

Method

Participants

Participants are members of the Environmental Risk (E-Risk) Longitudinal Twin Study, which investigates how genetic and environmental factors shape children’s development. The sampling frame from which the E-Risk families were drawn was two consecutive birth cohorts (1994 and 1995) in a birth register of twins born in England and Wales (Trouton, Spinath, & Plomin, 2002). Of the 15,906 twin pairs born in these 2 years, 71% joined the register.

The E-Risk Study probability sample was drawn using a high-risk stratification strategy. High-risk families were those in which the mother had her first birth when she was 20 years of age or younger. We used this sampling (1) to replace high-risk families who were selectively lost to the register via non-response and (2) to ensure sufficient base rates of problem behavior given the low base rates expected for 5-year-old children. Age at first childbearing was used as the risk-stratification variable because it was present for virtually all families in the register, it is relatively free of measurement error, and early childbearing is a known risk factor for children’s problem behaviors (Maynard, 1997; Moffitt & E-Risk Study Team, 2002). The high-risk sampling strategy resulted in a final sample in which one-third of study mothers constitute a 160% oversample of mothers who were at high risk based on their young age at first birth (13–20 years), while the other two-thirds of study mothers accurately represent all mothers in the general population (aged 13–48) in England and Wales in 1994–95 (estimates derived from the General Household Survey; Bennett, Jarvis, Rowlands, Singleton, & Haselden, 1996). To provide unbiased statistical estimates from the whole sample that can be generalized to the population of British families with children born in the 1990s, the data reported in this article were corrected with weighting to represent the proportion of maternal ages in that population.

The study sought a sample size of 1,100 families to allow for attrition in future years of the longitudinal study while retaining statistical power. An initial list of families who had same-sex twins was drawn from the register to target for home visits, with a 10% oversample to allow for nonparticipation. Of the 1,203 families from the initial list who were eligible for inclusion, 1,116 (93%; 51% female) participated in home-visit assessments when the twins were age 5 years, forming the base sample for the study: 4% of families refused, and 3% were lost to tracing or could not be reached after many attempts. With parent’s permission, questionnaires were posted to the children’s teachers, and teachers returned questionnaires for 94% of cohort children. Written informed consent was obtained from mothers. The E-Risk Study has received ethical approval from the Maudsley Hospital Ethics Committee. All research workers completed two weeks of formal training to attain standard on the measures reported here and had university degrees in behavioral science and experience in psychology, anthropology, or nursing.

A follow-up home visit was conducted 18 months after the twins’ age-5 assessment, when the children were on average 6 ½ years old (range 6.0 to 7.0 years). Follow-up data were collected for 98% of the 1,116 E-risk study families. At this follow-up, teacher questionnaires were obtained for 91% of the 2,232 E-risk study twins (93.0% of those taking part in the follow-up).

Measures

Weighted descriptive statistics for the sample overall and for non-maltreated, resilient, and non-resilient children are presented in Table 1. Measures included individual characteristics, family characteristics, and neighborhood characteristics that were measured when the children were 5 years old (measures that were administered during the age 7 interview are noted).

Table 1.

Means (SD) or Percentages (n) for Individual, Family, and Neighborhood Characteristics for Total Sample and Sub-Groups

| Maltreated

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Sample (n = 2,181) | Non-Maltreated (n = 1,895) | Resilient (n = 72) | Non-Resilient (n = 214) | Effect Size (d) Resilient vs. Non-maltreated | Effect Size (d) Resilient vs. Non-resilient | |

| Means (SD) or Percentages (n) | ||||||

| Individual Characteristics | ||||||

| Child sex (% male) | 49% | 49% | 57% | 51% | -- | -- |

| Above-avg. IQ | 33% | 34% | 39% | 26% | .12 | .31 |

| Well-adjusted temperament | 25% | 25% | 30% | 22% | .13 | .24 |

| Family Characteristics | ||||||

| Maternal warmth | .64 (.26) | .64 (.26) | .59 (.26) | .56 (.27) | .21 | .12 |

| Social deprivation | 1.18 (1.71) | 1.11 (1.65) | 1.53 (2.03) | 1.80 (1.96) | .25 | .14 |

| Maternal depression | 26% | 23% | 39% | 52% | .41 | .29 |

| Parent antisocial personality | 22% | 19% | 41% | 45% | .58 | .10 |

| Parent substance use problems | 22% | 20% | 26% | 42% | .21 | .39 |

| Adult domestic violence | 37% | 34% | 53% | 62% | .43 | .22 |

| Sibling warmtha | 10.22 (1.77) | 10.28 (1.75) | 9.83 (1.71) | 9.80 (1.92) | .26 | .01 |

| Sibling conflicta | 6.56 (2.86) | 6.40 (2.84) | 7.67 (2.09) | 7.76 (2.99) | .37 | .11 |

| Neighborhood factors | ||||||

| Crime | .82 (1.24) | .78 (1.20) | .69 (1.08) | 1.26 (1.59) | .08 | .38 |

| Social cohesion | 7.87 (2.56) | 7.98 (2.49) | 7.85 (2.22) | 6.75 (3.09) | .05 | 38 |

| Informal social control | 7.61 (2.63) | 7.73 (2.51) | 7.38 (2.77) | 6.37 (3.35) | .14 | .31 |

Measured at the age 7 assessment. All other measures from the age 5 assessment.

Individual characteristics

Children’s cognitive ability was measured using the short form of the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence-Revised (Wechsler, 1990). Following the procedure designed by Sattler (1992), we computed IQ scores based on children’s performance on the Vocabulary and Block Design sub-tests. Children with above-average IQ were defined as those who were at least half a standard deviation above the mean on the IQ measure.

Based on their observations of the children, research workers rated each twin on 25 different behavioral characteristics that assessed children's temperament (for details about this measure see Caspi, Henry, McGee, Moffitt, & Silva, 1995). Children with well-adjusted temperament were those who scored below the median on the under-controlled temperament scale (e.g., “easily frustrated,” “hostile”) as well as below the median on the shy temperament scale (e.g., “upset by strangers,” “self-confident,” reversed). Thus, children with well-adjusted temperament were sociable and self-controlled. The internal consistencies of these scales were both above .90.

Family characteristics

Maternal warmth was measured with the Expressed Emotion interview (e.g., Caspi et al., 2004). This measure refers to the emotions an adult expresses in his or her description of a child. Mothers were asked to speak for 5 minutes about each of their children. The content and quality of mothers’ speech (i.e., what mothers said and how they said it) was coded for positive or negative emotional valence to derive the total number of positive and negative comments made by mothers. The measure of maternal warmth used in the current analyses reflects the proportion of positive comments mothers made about each of their children.

Social deprivation reflects the sum of sociodemographic adversities that families faced (rated dichotomously as being present ‘1’ or absent ‘0’), including (1) lack of educational qualifications, (2) low socioeconomic status, (3) low income, (4) welfare receipt, (5) rental home, (6) household does not own or have access to a car or van, and (7) the neighborhood is characterized by a high proportion of public housing, poverty, single-parent families, and unemployment. For details about this measure, see Kim-Cohen and colleagues (2003).

Mothers’ major depressive disorder (MDD) was assessed using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS; Robins, Cottler, Bucholz, & Compton, 1995) according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-IV (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) criteria. Mothers were also asked about the timing of their depression relative to the twins’ birth; the variable used in our analysis reflects episodes of MDD that occurred after the children were born. Father’s and mother’s history of antisocial behavior was reported by mothers using the Young Adult Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, 1997), modified to obtain lifetime data and supplemented with questions from the DIS (Robins et al., 1995) that assessed the (lifetime) presence of DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) symptoms of Antisocial Personality Disorder (e.g., deceitfulness, aggressiveness). Mothers have been shown to be reliable informants about their partner’s antisocial behavior (Caspi et al., 2001). A symptom of antisocial personality disorder was considered to be present if the mother endorsed the symptom as being “very true or often true.” Children were coded as having an antisocial parent if either parent had three or more antisocial personality symptoms.

Mothers were asked a series of questions about drug and alcohol problems taken from the short Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (Selzer, Vinokur, & van Rooijen, 1975) and from the Drug Abuse Screening Test (Skinner, 1983). Mothers were asked these same questions about their children’s biological father. Internal consistency reliabilities for both scales were above .70. A symptom was considered to be present if the mother endorsed the symptom as being “very true or often true.” Crews and Sher (1992) reported that a cut-off score of four symptoms for mothers and five symptoms for fathers showed good agreement with clinical diagnoses of alcoholism. Thus, children were coded as living with a parent with substance use problems if either parent scored above the cut-point for substance use problems.

Adult domestic violence was assessed by inquiring about 12 acts of physical violence, including all 9 items from the Conflict Tactics Scale, Form R (Straus, 1990) plus 3 items describing other physically abusive behaviors (e.g., pushed/grabbed/shoved; beat up; threatened with knife or gun). Mothers were asked about their own violence toward any partner and about partners’ violence toward them during the 5 years since the twins’ birth, responding “not true” (coded 0) or “true” (coded 2). The domestic violence measure represents the variety of acts of violence mothers experienced as both victims and perpetrators. The internal consistency reliability of the physical abuse scale was .89. For additional information about the scale, see Jaffee, Moffitt, Caspi, Taylor, and Arseneault (2002). The measure of adult domestic violence used in this manuscript reflects whether children lived in homes where there was any adult domestic violence versus no adult domestic violence.

At the age 7 assessment, mothers were asked a series of questions about the quality of their children’s relationship with one another. Mothers responded on a 3-point scale ranging from 0 ‘no’ to 2 ‘yes’ to 6 questions about sibling warmth (e.g., “do your twins love each other,” “do both your twins do nice things for each other;” alpha = .76) and 6 questions about sibling conflict (e.g., “do your twins insult and call each other names,” “do your twins disagree and quarrel with each other;” alpha = .83).

Neighborhood characteristics

Crime was assessed by asking mothers whether their family had been victimized by violent crime (e.g., mugging, assault), a burglary or home break-in, or a theft. Informal social control and social cohesion (Sampson, Raudenbush, & Earls, 1997) were each assessed with five items to which mothers responded from 0 “no, not true” to two “yes, very true.” Informal social control was assessed by asking mothers to judge whether people in their neighborhoods would take action against five different types of threats (e.g., children skipping school and hanging around, fight in a public place; alpha = .75). Social cohesion was assessed by asking mothers whether their neighborhoods were close-knit, whether neighbors helped one another and shared values, and whether neighbors trusted and got along with each other (alpha = .83).

Child behavior

At ages 5 and 7, teachers were asked to complete the Teacher Report Form (Achenbach, 1991) which assesses children’s antisocial behavior (e.g., “gets in many fights,” “destroys property belonging to others”), emotional problems (e.g, “unhappy, sad, or depressed,” “nervous, high-strung, or tense”), and prosocial behavior (“shares treats with friends,” “considerate of other people’s feelings”). Internal consistency reliabilities exceeded .75 for these scales.

Reading ability

Children were administered the Test of Word Reading Efficiency (TOWRE), which measures a child's ability to pronounce printed words accurately and fluently (Torgesen, Wagner, & Rashotte, 1999). The TOWRE contains two subtests. The Sight Word Efficiency subtest measures the number of real printed words that can be accurately identified within 45 seconds; the Phonemic Decoding Efficiency subtest measures the number of pronounceable printed non-words that can be accurately decoded in 45 seconds. Raw scores were converted to age-standardized scores. Our analysis included a variable that measured whether children were reading at or above the median for the sample.

Resilience to maltreatment

At the age 5 assessment, mothers were administered the standardized clinical interview protocol from the Multi-Site Child Development Project to assess whether either of their children had ever been physically maltreated (Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 1990; Dodge, Pettit, Bates, & Valente, 1995; Lansford et al., 2002). We interviewed mothers instead of ascertaining cases from Child Protective Service registers for three reasons. First, official record data identify only a small proportion of cases, which may be a biased, unrepresentative subset (Walsh, McMillan, & Jamieson, 2002; Widom, 1988). Second, because of time delays in detection, investigation, and legal proceedings against perpetrators, official record data sources tend not to record children as confirmed cases until older ages and the children in our sample were 5 years old. Third, searching child protection records for this sample would have required parental consent, placing record data at the same potential risk of parental concealment as mothers’ reports.

The interview protocol was designed by Dodge and colleagues (Dodge et al., 1990; Dodge et al., 1995; Lansford et al., 2002) to enhance mothers' comfort with reporting valid child maltreatment information, while also meeting researchers' legal and ethical responsibilities for reporting. Under the UK Children Act (Department of Health, 1989), our responsibility was to secure intervention if maltreatment was current and ongoing. At the start of the interview about discipline and physical maltreatment, the interviewer explained to the mother that if she reported maltreatment that had occurred in the child’s first 4 years and was not ongoing, that information could remain confidential. However, if she reported maltreatment that occurred in the year prior to the interview and the risk to the child was ongoing, study staff would be under legal obligation to assist the family to get help. Thus, when mothers gave informed consent to proceed with the interview they understood that a report of recent, ongoing maltreatment would constitute a request for help (if the maltreatment was not already known to authorities). The interview did not ask directly about the timing of incidents, and, therefore, mothers who wished to report maltreatment while avoiding intervention could have opted to describe maltreatment as happening in the past. There was a need to intervene on behalf of 15 families. We found that almost all current cases of maltreatment were already known to government home health visitors, the family’s general practitioner, or child protection teams, although very few of the cases had been officially registered.

The protocol included standardized probe questions such as, "When [name] was a toddler, do you remember any time when s/he was disciplined severely enough that s/he may have been hurt?" and "Did you worry that you or someone else [such as a babysitter, a relative or a neighbor] may have harmed or hurt [name] during those years?" (1% of mothers declined to answer the questions). The same set of questions about physical maltreatment was asked individually about each twin, and the interviews about each twin were separated by 1.5 hours of questions on other topics. Questions were carefully worded to avoid implying that the mother was the perpetrator, so mothers might feel more willing to report that a child had been maltreated. In cases where mothers reported any physical maltreatment, interviewers probed mothers for details about the incident and recorded notes. Interviewers coded the likelihood that the child had been maltreated based on the mothers’ narrative. This classification showed inter-coder agreement on 90% of ratings (kappa = .56) in the Dodge et al. study (Dodge, Pettit, & Bates, 1994; Dodge et al., 1995) and ours. The 10% of codes that disagreed tended to reflect uncertainty about whether physical maltreatment was “probable” or “definite.”

Based on the mother’s report of the severity of discipline and the interviewer’s rating of the likelihood that the child had been physically maltreated, children were coded as having not been, possibly been, or definitely been physically maltreated. Examples of possible physical maltreatment in our sample (N = 273 children) included instances where the mother reported that she smacked the child harder than intended and left a mark or bruise, or cases where social services were contacted by schools, neighbors, and/or family members out of concern that the child was being physically maltreated. Examples of definite physical maltreatment included children who were beaten by a teenaged step-sibling, punished by being burnt with matches or thrown against doors, had injuries (e.g., fractures or dislocations) from neglectful or abusive care, or were formally registered with a social services child protection team. The prevalence of such definite, serious physical maltreatment as defined in this sample was 1.5% (N = 34 children).

For the purposes of our analyses, the child physical maltreatment variable was recoded into a dichotomous variable representing children who experienced no physical maltreatment (unweighted, the prevalence was 86%; weighted to represent the population it was 88%) versus a combined group of children who experienced possible or definite physical maltreatment (unweighted, the prevalence was 14%; weighted to represent the population it was 12%). Our combined prevalence of 12% resembles the 15% prevalence estimate reported by Dodge and colleagues (Dodge et al., 1990) whose measurement protocol we used.

The physical maltreatment interview protocol has (a) good concurrent validity as evidenced by correlations above .60 with mothers’ reports of their child-directed aggression using the Conflict Tactic Scales (Dodge et al., 1990; Straus & Gelles, 1988), (b) good inter-reporter reliability as evidenced by a correlation of .60 between mothers’ and fathers’ reports in 396 couples (Dodge et al., 1995), and (c) good predictive validity as evidenced by significant 12-year prediction from preschool maltreatment to outcomes in grade 11, including increased violence, school absenteeism, anxiety and depressive symptoms, and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms, controlling for a variety of social and family risk factors (Lansford et al., 2002).

Data analysis strategy

Multinomial logistic regression analyses were conducted to (a) compare non-maltreated, resilient, and non-resilient children on measures of adaptive functioning and (b) to test whether individual, family, and neighborhood factors distinguished resilient from non-resilient children. Multinomial logistic regression analyses estimated the relative risk of being in one category (e.g., non-resilient) relative to a reference category (e.g., resilient) as a function of individual, family, and neighborhood covariates.

Because our twin study included two children from each family, observations of children’s behavior were non-independent. Therefore, we analyzed the data using standard regression techniques but with all tests based on the sandwich or Huber/White variance estimator (Rogers, 1993; Williams, 2000), a method available in STATA 7.0. (StataCorp, 2001). Application of this technique adjusts estimated standard errors and, therefore, accounts for the dependence in the data due to analyzing sets of twins.

Results

Defining resilience

We defined resilience on the basis of children’s history of maltreatment and their teachers’ reports of their antisocial behavior. Because boys had significantly higher levels of antisocial behavior than girls, children were compared to other children of their same sex. Children who had never been maltreated were assigned to the non-maltreated group (unweighted n = 1895; weighted proportion = 88%). Children who had been maltreated and whose antisocial behavior scores at ages 5 and 7 fell at or below the median for the non-maltreated group at those ages were assigned to the resilient group (unweighted n = 72; weighted proportion = 3%). Children who had been maltreated and whose antisocial behavior scores exceeded the median for the non-maltreated group at age 5 or 7 were assigned to the non-resilient group (unweighted n = 214, weighted proportion = 9%). To be categorized as resilient, children had to have non-missing antisocial behavior scores at both time points (21 children did not).

Our definition of resilience among children who had been maltreated was relatively stringent in requiring that antisocial behavior scores fall at or below the median for the non-maltreated group at both ages 5 and 7. Indeed, only 32% of the non-maltreated children were considered resilient by these criteria although, by definition, 50% of non-maltreated children were resilient at either age 5 or age 7. Among those children who had been maltreated and whose antisocial behavior scores at age 5 did not exceed the median for the non-maltreated group, 64% remained at or below the median for the non-maltreated group at age 7. Resilience at age 5 increased the odds of resilience at age 7 by a factor of 5 (OR = 5.37, 95% C. I. = 2.89 to 9.99, p ≤ .001).

Testing the validity of the resilience construct

Our definition of resilience was based on maltreated children’s relatively low levels of antisocial behavior. To test whether children classified as resilient were achieving other normative developmental tasks, we compared resilient children, non-resilient children, and children who had never been maltreated on a range of outcomes that reflected competence in mental health, social relationships, and academic achievement (Table 2). Teachers reported that resilient children had fewer emotional problems than non-resilient children (at age 7 but not at age 5), engaged in more prosocial behavior, and were more likely to have average or above-average reading ability. Effect sizes comparing resilient and non-resilient children were moderate in magnitude. In contrast, resilient children and non-maltreated children did not differ significantly on these variables. Effect sizes comparing resilient and non-maltreated children were generally small in magnitude. Thus, resilient children were not only doing better than non-resilient children on measures of emotional problems, prosocial behavior, and reading ability, but they were doing as well as children who had never been maltreated.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for Non-Maltreated, Resilient, and Non-Resilient Children on Emotional Problems, Prosocial Behavior, and Reading Ability

| Maltreated

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non- Maltreated | Resilient | Non-Resilient | Regression Model Fit | Resilient vs. Non-Maltreated | Resilient vs. Non-Resilient | |

| Means (SD) | F (df) | effect size | effect size | |||

| Emotional problems at 5 | 5.37 (5.31) | 4.76 (4.39) | 5.34 (5.49) | .56 (2, 1047) | .12 | .11 |

| Emotional problems at 7 | 5.14 (5.41) | 4.27 (4.63) | 6.79 (6.88) | 5.24 (2, 1024)** | .16 | .40** |

| Prosocial behavior at 5 | 11.85 (4.89) | 12.93 (3.74) | 10.25 (4.63) | 9.80 (2, 1024)*** | .22 | .61*** |

| Prosocial behavior at 7 | 12.80 (4.75) | 13.80 (4.93) | 11.40 (5.09) | 5.74 (2, 1021)*** | .21 | .48** |

| Percentages (n) | Wald χ2 (df) | OR (95% C. I.) (effect size) | OR (95% C. I.) (effect size) | |||

| Average or above -average reading scores at 7 | 57.2 (964) | 64.5 (44) | 49.2 (85) | 4.91 (2) | 1.38 (.79; 2.35) (.17) | 1.88 (1.02; 3.47)* (.35) |

p ≤ .001,

p ≤ .01,

p ≤ .05

Note: OR = odds ratio; ORs are transformed to compare (a) resilient versus non-maltreated and (b) resilient versus non-resilient children.

Do individual, family, and neighborhood factors distinguish resilient children from non-resilient and non-maltreated children?

To test whether individual, family, and neighborhood factors distinguished resilient from non-resilient (and non-maltreated) children, we conducted a series of multinomial logistic regression analyses. Resilient children were the reference category in these analyses. However, in Table 3 we transformed the relative risk ratios (RRRs) so that RRRs greater than 1.0 indicated that any given characteristic (e.g., high IQ) was more prevalent among children in the resilient group than the other two groups and RRRs less than 1.0 indicated that a given characteristic was less prevalent among children in the resilient group than the other two groups (e.g., RRRresilient vs. non-resilient = 1/RRRnon-resilient vs. resilient).

Table 3.

Multinomial Logistic Regression Analyses: Individual, Family, and Neighborhood Characteristics Distinguish Resilient from Non-Resilient and Non-Maltreated Children

| Resilient versus Non-Resilient | Resilient versus Non-Maltreated | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RRR | 95% Confidence Interval | RRR | 95% Confidence Interval | |

| Individual Characteristics | ||||

| Child sex | 1.29 | .66 to 2.53 | 1.39 | .74 to 2.59 |

| Above-average IQ | 1.75a | .91 to 3.35 | 1.23 | .71 to 2.14 |

| Well-adjusted temperament | 1.54 | .72 to 3.31 | 1.27 | .65 to 2.48 |

| Family characteristics | ||||

| Social deprivation | .93 | .80 to 1.09 | 1.14 | .98 to 1.32 |

| Maternal depression | .59 | .30 to 1.15 | 2.10* | 1.12 to 3.96 |

| Parental antisocial personality symptoms | .84a | .44 to 1.62 | 2.87*** | 1.55 to 5.31 |

| Parental substance use problems | .49* | .24 to 1.00 | 1.46 | .75 to 2.84 |

| Adult domestic violence | .67 | .34 to 1.32 | 2.18* | 1.17 to 4.07 |

| Maternal warmth | 1.50 | .57 to 3.89 | .46 | .20 to 1.08 |

| Sibling conflict | .96 | .87 to 1.06 | 1.14** | 1.05 to 1.23 |

| Sibling warmth | 1.01 | .86 to 1.17 | .87 | .76 to 1.00 |

| Neighborhood characteristics | ||||

| Crime | .72** | .57 to .92 | .94 | .74 to 1.18 |

| Social cohesion | 1.12* | 1.00 to 1.26 | .95 | .86 to 1.06 |

| Informal social control | 1.15** | 1.04 to 1.27 | .98 | .89 to 1.08 |

p ≤ .001,

p ≤ .01,

p ≤ .05

Note: RRR = relative risk ratio. RRR is transformed so that non-resilient children are the reference category in columns 1 & 2 and non-maltreated children are the reference category in columns 3 and 4.

Main effect is qualified by a significant interaction with child sex.

Comparing resilient and non-resilient children

The results in the first and second columns of Table 3 show that gender, high IQ, and well-adjusted temperament did not distinguish resilient from non-resilient children. However, a significant interaction was detected between child sex and IQ (RRR = 5.28, 95% C. I. = 1.30 to 21.43, p ≤ .05). For boys, high IQ increased the relative risk of being resilient versus non-resilient by 3.87 (95% C. I. = 1.70 to 8.87, p ≤ .001). For girls, IQ was not associated with resilience status (RRR = .73, 95% C. I. = .24 to 2.27, p = .59).

Having a parent with substance use problems decreased the likelihood of being resilient rather than non-resilient, but none of the other family characteristics distinguished resilient from non-resilient children. The interaction between child sex and parent symptoms of antisocial personality was also significant (RRR = .24, 95% C. I. .06 to .90, p ≤ .05). Boys whose parents had symptoms of antisocial personality were only half as likely to be resilient as they were to be non-resilient to maltreatment (RRR = .43, 95% C. I. .19 to .92, p ≤ .05). However, parent symptoms of antisocial personality did not distinguish resilient from non-resilient girls (RRR = 1.79, 95% C. I. .64 to 5.00, p = .26). None of the other interactions between child sex and family characteristics were significant.

As shown in the last three rows of columns 1 and 2 (Table 3), children who lived in higher crime neighborhoods were less likely to be resilient to maltreatment than they were to be nonresilient. Children who lived in neighborhoods characterized by higher levels of social cohesion and high levels of informal social control were more likely to be resilient to maltreatment than they were to be non-resilient. Tests of the interactions between neighborhood characteristics and child sex showed that neighborhood characteristics did not differ in the degree to which they distinguished resilient from non-resilient boys or girls.

Comparing resilient and non-maltreated children

The results in the third and fourth columns of Table 3 show that neither gender, above-average IQ, nor well-adjusted temperament distinguished children who were resilient to maltreatment from those who were not maltreated. However, children whose mothers had been clinically depressed, whose parents had symptoms of antisocial personality, whose parents reported adult domestic violence, and who had conflictual relationships with their siblings were more likely to be resilient to maltreatment versus non-maltreated. Neighborhood characteristics did not distinguish resilient from non-maltreated children. There were no significant interactions between child sex and any of the individual, family, or neighborhood characteristics.

Testing a cumulative stressors model

As reported above, boys who had high IQ were significantly more likely to be resilient than they were to be non-resilient to maltreatment (RRR = 3.87). Moreover, although the effect was not statistically significant, boys who were temperamentally well-adjusted were also more likely to be resilient than they were to be non-resilient to maltreatment (RRR = 2.78, 95% C. I. = .91 to 8.53, p = .07). We tested whether these individual strengths (high IQ or well-adjusted temperament; in sample overall, n = 912, weighted percentage = 46%) distinguished resilient from non-resilient children no matter how many family and neighborhood stressors the children experienced. Even though the main effects of individual strengths were not significant for girls, girls and boys were included in this analysis because the lack of main effects does not preclude the detection of significant interaction terms.

We created a cumulative stressors variable by counting the following stressors: (1) maternal depression since the birth of the children, (2) clinically-significant parent substance use problems, (3) 3 or more symptoms of parent antisocial personality disorder, (4) social deprivation (high social deprivation was captured by a score of 2 or higher; 28% of sample), (5) troubled sibling relations (characterized by scores above the 50th percentile for sibling conflict and below the 50th percentile for sibling warmth), (6) low maternal warmth (more than half the statements mothers made about children were negative), (7) adult domestic violence, (8) neighborhood crime (characterized by scores of 2 or higher on the criminal victimization scale), (9) low social cohesion (bottom 30th percentile), and (10) low social control (bottom 30th percentile). Scores ranged from 0 to 10 (M = 2.99, SD = 2.20). There was a small amount of missing data across the 10 dichotomous variables that were included in the cumulative stressors composite. Thus, to create the cumulative stressors variable, we prorated scores for individuals who were missing data on less than half of the 10 stressor variables (15%). The vast majority of prorated scores (90%) came from individuals who were missing data for only 1 stressor.

A negative binomial regression analysis was conducted to determine whether non-maltreated, resilient, and non-resilient children differed on the number of stressors to which they were exposed. As predicted, non-resilient children were exposed to significantly more stressors than resilient children (b = .23, SE = .10, p ≤ .05) and non-maltreated children were exposed to significantly fewer stressors than resilient children (b = .32, SE = .09, p ≤ .001).

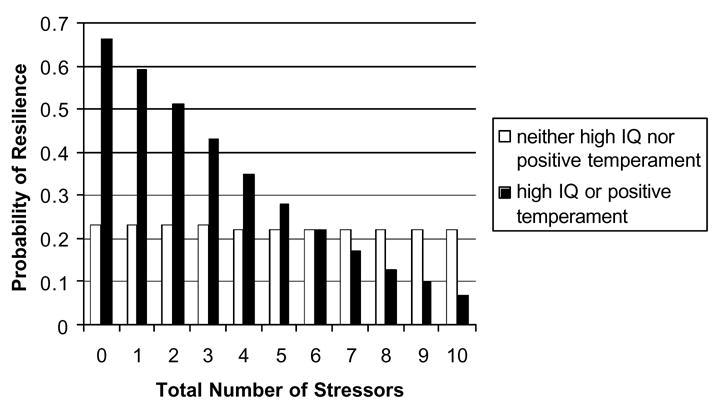

The results of a hierarchical multinomial logistic regression analysis yielded a significant interaction between children’s individual strengths and cumulative stressors (RRR = 1.34, SE = .16, 95% C. I. = 1.08 to 1.68, p ≤ .01). Figure 1 graphs the predicted probability of being resilient to maltreatment as a function of children’s individual strengths. This figure excludes children who were not maltreated. Children who possessed strengths were more likely to be resilient to maltreatment than children who did not, but only under conditions of relatively low stress. For example, under conditions of low stress (e.g., no more than 1 stressor), children who possessed strengths were highly likely to be resilient (59% probability or higher) but under conditions of high stress (e.g., 4 or more stressors), children who possessed strengths were decreasingly likely to be resilient (35% probability or less). In contrast, only about 20% of children who did not possess strengths were resilient to maltreatment, regardless of their exposure to increasing numbers of family and neighborhood stressors.

Figure 1.

The probability of children’s resilience to maltreatment as a function of individual strengths and exposure to family and neighborhood stressors.

Discussion

In a group of children who had been maltreated before the age of 5 years, individual, family, and neighborhood characteristics were associated with behavioral resilience. Boys who had above-average intelligence and whose parents had few symptoms of antisocial personality were more likely to be resilient than non-resilient. Similarly, children whose parents were free of substance use problems and who lived in lower-crime neighborhoods characterized by higher levels of social cohesion and informal social control were more likely to be resilient than non-resilient to maltreatment. However, exposure to multiple family and neighborhood stressors severely compromised children’s resilience, particularly when children possessed individual strengths that, under low-stress conditions, protected them from the adverse effects of maltreatment.

Defining resilience

Previous research with this sample has shown that physical maltreatment increases children’s risk of antisocial behavior (Jaffee et al., 2005; Jaffee, Caspi, Moffitt, & Taylor, 2004). However, not all children who were maltreated were characterized by behavior problems at the age when they were making the transition to school. Among children who were physically maltreated, approximately a quarter were defined as resilient based on teachers’ reports that the children engaged in average or below-average levels of antisocial behavior compared to their same-sex non-maltreated peers. Although our definition of resilience was based on children’s antisocial behavior, children who we defined as resilient showed age-appropriate competencies across a range of outcomes. For instance, resilient children looked similar to non-maltreated children and better than non-resilient children in terms of other aspects of their mental health (e.g., anxious, depressed behavior), their prosocial skills, and their reading skills. Similarities between resilient and nonmaltreated children did not arise because both groups were exposed to equally low levels of family and neighborhood stressors. Resilient children faced more family stressors than non-maltreated children but were functioning at an equivalently high level, at least during the early school years. Thus, resilient children were achieving normative developmental tasks across multiple points in time and according to different teachers who rated their behavior and abilities.

Our definition of resilience required that children show adaptive functioning at two different time points. However, adaptive functioning from age 5 to 7 showed evidence of both change and stability. On the one hand, children who were resilient to maltreatment when they were 5 years old were significantly more likely to be resilient to maltreatment when they were 7 years old compared to children who were not resilient at age 5. On the other hand, approximately a third of children who would have been considered resilient to maltreatment when they were 5 years old were not resilient 2 years later. These findings are consistent with results from other studies that identify change over time in resilience (Jaffee, 2006; Kaufman et al., 1994). Future research should explore factors that promote change and stability in children’s resilience to maltreatment over time.

Individual, family, and neighborhood characteristics associated with resilience

Our findings are consistent with the extant literature in showing that individual, family, and neighborhood factors are associated with resilience to maltreatment (Cicchetti et al., 1993; Cicchetti & Rogosch, 1997; Feiring et al., 2002; Herrenkohl et al., 1994; Moran & Eckenrode, 1992). Our findings add to this literature by identifying factors that are associated with persistent resilience, at least over a 2-year period, as opposed to resilient functioning at a single point in time. Moreover, we identified a pattern of gender differences in the correlates of resilience that, to our knowledge, has not been identified by other groups.

Boys and girls were equally likely to have been physically maltreated and equally likely to be resilient. However, individual strengths played a more important role in distinguishing resilient from nonresilient boys rather than girls. It is possible that boys who are bright, sociable, and self-controlled attract more attention and support from teachers and other adults than girls who possess similar strengths, particularly when adults know or suspect that boys come from difficult home environments and when these strengths are typically less characteristic of boys than girls. It may also be that individual strengths make girls resilient in other ways. For example, if resilience was defined in terms of depression and anxiety rather than antisocial behavior, the results might have been different. Moreover, there was some evidence that family risk factors (e.g., parental antisocial personality symptoms) had stronger effects on boys than girls. It is necessary that interaction effects be replicated in other samples, and specific hypotheses about gender differences be generated and tested empirically. We note that, despite these gender differences in main effects of individual strengths and family risk factors, there was a significant interaction for boys and girls between individual strengths and family and neighborhood stressors such that individual strengths distinguished resilient from non-resilient children under conditions of low, but not high, stress.

Transactional models of children’s functioning

Our findings contribute to the extant literature on children’s resilience to maltreatment by illustrating the importance of studying the interplay among risk and protective factors. Transactional models of development highlight the need to study the individual within context (Sameroff & Chandler, 1975; Sameroff & MacKenzie, 2003). This approach proposes that a person’s outcomes cannot be predicted from individual characteristics alone, nor from a singular focus on the person’s life circumstances, but rather from the fit between individuals and their environments. To date, most studies of children’s resilience to maltreatment have focused on identifying specific factors that promote positive functioning without considering whether these protective factors interact with other risk and protective factors operating at different levels of the child’s ecology.

Although resilient children were exposed to fewer family and neighborhood stressors than non-resilient children, this fact alone did not explain their better outcomes. Rather, compared to non-resilient boys, resilient boys possessed personal strengths like high IQ that predicted their positive functioning. However, these personal strengths were not associated with resilience under all conditions. When children faced multiple family and neighborhood stressors, personal strengths failed to distinguish those who were resilient to maltreatment from those who were not. This finding is consistent with a number of reports in the literature (Luthar, 1991; Sameroff, Bartko, Baldwin, Baldwin, & Seifer, 1998) and underscores the basic premise of the transactional approach. The protective effects of children’s individual strengths must be understood within the context of children’s life circumstances.

It bears noting that family and neighborhood adversities had to be extreme before they impinged upon children’s individual strengths. All the resilient and non-resilient children in our sample were under at least some stress because they had all been victims of maltreatment. An examination of Figure 1 shows that individual strengths failed to predict resilience only when children were experiencing multiple family or neighborhood stressors in addition to maltreatment. This pattern of effects is consistent with Scarr’s proposition (Scarr, 1992) that children’s individual characteristics are expressed and account for variability in children’s outcomes when children are raised within the expectable range of caregiving environments, but not when children’s circumstances fall outside the range of normative caregiving environments. Our findings suggest that children who possess individual strengths and who can be protected from significant ongoing family and neighborhood stressors stand a good chance of maintaining positive functioning in the long-term. This, however, is an empirical proposition that must be put to the test with longitudinal data.

Implications for practice

Cumulative stress models underscore the fact that risk factors tend to accumulate within particular families. Cumulative effects also refer to the adverse consequences for the child of exposure to multiple family and neighborhood risks and the degree to which these consequences accumulate in strength over time. A basic premise of the transactional model is that the relationship between the individual and his or her environment is bidirectional (Sameroff & MacKenzie, 2003). The child who has experienced adversity but is bright and sociable and is doing well in school is likely to elicit support from teachers and from other children that will further foster positive adaptation. This child will go from strength to strength. In contrast, the child who is struggling in school and who is aggressive and uncooperative is more likely to be rejected by peers and adults, thereby increasing the child’s risk for persistent maladaptation (Caspi & Moffitt, 1995). The sooner practitioners can intervene to break this negative bidirectional chain, the better the chances of fostering positive adaptation across multiple domains.

Our findings lend support to the efforts of multisystemic interventions that target multiple levels of the child’s ecology, including characteristics of the child and the child’s family. Neighborhood factors may impinge directly on children or indirectly via their effects on parents’ emotional well-being and parenting practices. Given that the individual strengths we measured are not easy to modify (e.g., IQ and temperament are moderately to highly stable over time) intervention researchers may have more success in modifying behaviors that arise as a consequence of maltreatment (e.g., children’s aggressive, antisocial behavior or school difficulties). Regardless of which individual characteristics become the focus of intervention efforts, our data suggest that such efforts must also focus on parents’ well-being and, potentially, characteristics of the neighborhoods in which children live in an effort to determine how parents and children can be helped to cope with the challenges of residence in dangerous, isolated communities. Interventions should attempt to minimize the number of family and neighborhood stressors children experience so that children can draw on innate personal resources or on those that are fostered through the intervention process.

Limitations

Our conclusions are characterized by several limitations. First, it is possible that children who we defined as resilient managed to function well because they had experienced relatively less severe or chronic episodes of maltreatment. Although we did not collect information about the severity or duration of abuse, we do know how many children were judged to be possibly maltreated versus definitely maltreated based on the research workers’ interviews with the children’s mothers (these children were combined into one maltreated group in this paper). Eleven percent of the children who were resilient to maltreatment had been definitely maltreated whereas 7% of the children who were not resilient to maltreatment had been definitely maltreated. Thus, to the degree that the research workers’ certainty that the child had been physically maltreated can be treated as an index of the severity of the abuse, we can conclude that children who were resilient to maltreatment potentially experienced more severe abuse than non-resilient children, though differences between the two groups are unlikely to be statistically significant.

Second, the proportion of children who were defined as resilient and the factors that distinguished resilient from non-resilient children might have varied depending on what type of abuse children experienced. However, we did not ask caregivers about specific forms of maltreatment other than to ascertain that children had been physically maltreated. Other studies have largely failed to find support for the hypothesis that different factors protect children who have experienced different forms of maltreatment (e.g., physical vs. sexual abuse; Cicchetti & Rogosch, 1997; McGloin & Widom, 2001). Indeed, this may be because many children who are victims of one type of maltreatment experience multiple forms of maltreatment.

Third, the children in our sample were twins. Although twin infants are more likely to be abused than singletons (Groothuis et al., 1982), studies of singletons have shown that cumulative stressors exert the same adverse effects on child behavior (and on factors that promote positive child well-being) as we demonstrated in this paper.

Fourth, our decision to create an index of family and neighborhood risk factors has advantages and disadvantages. On the one hand, this approach fails to address the possibility that specific risk factors are disproportionately influential, although empirical tests of this hypothesis have not found support for it (e.g., Deater-Deckard, Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 1998; Sameroff, Seifer, Baldwin, & Baldwin, 1993). On the other hand, this approach recognizes that risk factors tend to be correlated. Short of an experimental design, it is not only difficult to estimate the influence of one risk factor independent from the others, but statistical controls for over-lapping risk factors may not reflect the realities of multi-problem families.

Conclusion

In summary, individual, family, and neighborhood risk factors all distinguished resilient from non-resilient children, but resilience was influenced by the interplay among these different levels of risk and protection. Individual strengths, such as an above-average IQ or an easy-going temperament distinguished resilient from non-resilient maltreated children when children were exposed to relatively few stressors, but not when children were exposed to multiple stressors.

Child maltreatment is a significant public health concern because children who are physically maltreated are at risk of a range of adverse outcomes in childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. Nevertheless, some children who are maltreated manage to function well. The challenge for researchers and practitioners is to discover what combination of individual, family, and extra-familial resources are available to these children, how these factors work to promote positive well-being, and whether they help to maintain positive adaptation over the long-term.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Study mothers and fathers, the twins, and the twins’ teachers for their participation. Our thanks to Michael Rutter and Robert Plomin for their contributions, to Thomas Achenbach for kind permission to adapt the CBCL, to Hallmark Cards for their support, and to members of the E-Risk team for their dedication, hard work, and insights.

Footnotes

The E-Risk Study is funded by the Medical Research Council grant number G9806489 and by the UK-Economic and Social Research Council Network for the Study of Social Contexts for Pathways In Crime.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Teacher's Report Form and 1991 profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Young Adult Self-Report and Young Adult Behavior Checklist. Burlington: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual. 4. Washington DC: Authors; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Appel AE, Holden GW. The co-occurrence of spouse and physical child abuse: A review and appraisal. Journal of Family Psychology. 1998;12:578–599. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett N, Jarvis L, Rowlands O, Singleton N, Haselden L. Living in Britain: Results from the General Household Survey. London: HMSO; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Henry B, McGee RO, Moffitt TE, Silva PA. Temperamental origins of child and adolescent behavior problems: From age 3 to age 15. Child Development. 1995;66:55–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, McClay J, Moffitt TE, Mill J, Martin J, Craig IW, Taylor A, Poulton R. Role of genotype in the cycle of violence in maltreated children. Science. 2002;297:851–854. doi: 10.1126/science.1072290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Moffitt TE. The continuity of maladaptive behavior: From description to understanding in the study of antisocial behavior. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology. 1. New York: Wiley; 1995. pp. 472–511. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Morgan J, Rutter M, Taylor A, Arseneault L, Tully L, Jacobs C, Kim-Cohen J, Polo-Tomas M. Maternal expressed emotion predicts children's antisocial behavior problems: Using monozygotic-twin differences to identify environmental effects on behavioral development. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:149–161. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Taylor A, Smart M, Jackson J, Tagami S, Moffitt TE. Can women provide reliable information about their children's fathers? Cross-informant agreement about men's lifetime antisocial behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2001;42:915–920. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Manly JT. Operationalizing child maltreatment: Developmental processes and outcomes. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13(4) Ref Type: Journal (Full) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. The role of self-organization in the promotion of resilience in maltreated children. Development and Psychopathology. 1997;9:797–815. doi: 10.1017/s0954579497001442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA, Lynch M, Holt KD. Resilience in maltreated children: Processes leading to adaptive outcome. Development and Psychopathology. 1993;5:629–647. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth SL. A developmental psychopathology perspective on child abuse and neglect. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry. 1995;34:541–565. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199505000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews TM, Sher KJ. Using adapted short MASTs for assessing parental alcoholism: Reliability and validity. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1992;16:576–584. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1992.tb01420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson-Arad B, Englechin-Segal D, Wozner Y. Short-term follow-up of children at risk: Comparison of the quality of life of children removed from home and children remaining at home. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2003;27:733–750. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(03)00113-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Multiple risk factors in the development of externalizing behavior problems: Groups and individual differences. Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:469–493. doi: 10.1017/s0954579498001709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. The Children Act. London: HMSO; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Mechanisms in the cycle of violence. Science. 1990;250:1678–1683. doi: 10.1126/science.2270481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE. Socialization mediators of the relation between socioeconomic status and child conduct problems. Child Development. 1994;65:649–665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE, Valente E. Social information-processing patterns partially mediate the effect of early physical abuse on later conduct problems. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1995;104:632–643. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.104.4.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edleson JL. The overlap between child maltreatment and woman battering. Violence Against Women. 1999;5:134–154. [Google Scholar]

- Egeland B, Carlson EA, Sroufe LA. Resilience as process. Development and Psychopathology. 1993;5:517–528. [Google Scholar]

- Feiring C, Taska L, Lewis M. Adjustment following sexual abuse discovery: The role of shame and attributional style. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:79–92. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley DL, Eaves LJ, Wormley B, Silberg JL, Maes HH, Riley B. Childhood adversity, monoamine oxidase A genotype, and risk for conduct disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:744. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.7.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garmezy N. Stress-resistant children: The search for protective factors. Recent research in developmental psychopathology. In: Stevenson JE, editor. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry Book Supplement No 4. Oxford: Pergamon Press; 1985. pp. 213–233. [Google Scholar]

- Gelles RJ. Poverty and violence toward children. American Behavioral Scientist. 1992;35:258–274. [Google Scholar]

- Groothuis JR, Altmeier WA, Robarge JP, O'Connor S, Sandler H, Vietze P, Lustig JV. Increased child-abuse in families with twins. Pediatrics. 1982;70:769–773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart J, Gunnar M, Cicchetti D. Altered neuroendocrine activity in maltreated children related to symptoms of depression. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:201–214. [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Newport DJ, Bonsall R, Miller AH, Nemeroff CB. Altered pituitary-adrenal axis responses to provocative challenge tests in adult survivors of childhood abuse. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:575–581. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.4.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrenkohl EC, Herrenkohl R, Egolf M. Resilient early school-age children from maltreating homes: Outcomes in late adolescence. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1994;64:301–309. doi: 10.1037/h0079517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz AV, Widom CS, McLaughlin J, White HR. The impact of childhood abuse and neglect on adult mental health: A prospective study. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2001;42:184–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee SR. Family violence and parent psychopathology: Implications for children's socioemotional development and resilience. In: Goldstein S, Brooks R, editors. Handbook of resilience in children. New York: Kluwer; 2005. pp. 149–163. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee SR. The prevalence and stability of resilience to maltreatment: Results from a nationally-representative sample of children in the United States. 2006. Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee SR, Belsky J, Harrington H, Caspi A, Moffitt TE. When parents have a history of conduct disorder: How is the caregiving environment affected? Journal of Abnormal Psychology. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.2.309. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee SR, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Dodge KA, Rutter M, Taylor A, Tully LA. Nature x nurture: Genetic vulnerabilities interact with child maltreatment to promote conduct problems. Development and Psychopathology. 2005;17:67–84. doi: 10.1017/s0954579405050042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee SR, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Taylor A. Physical maltreatment victim to antisocial child: Evidence of an environmentally mediated process. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:44–55. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee SR, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Taylor A, Arseneault L. Influence of adult domestic violence on children's internalizing and externalizing problems: An environmentally informative twin study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41:1095–1103. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200209000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Cook A, Arny L, Jones B, Pittinsky T. Problems defining resiliency: Illustrations from the study of maltreated children. Development and Psychopathology. 1994;6:215–229. [Google Scholar]

- Kim-Cohen J, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Harrington H, Milne BJ, Poulton R. Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:709–717. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE, Crozier J, Kaplow J. Long-term effects of early child physical maltreatment on psychological, behavioral, and academic problems in adolescence: A 12-year prospective study. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2002;156:824–830. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.8.824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS. Vulnerability and resilience: A study of high-risk adolescents. Child Development. 1991;62:600–616. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01555.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS. Annotation: Methodological and conceptual issues in research on childhood resilience. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1993;34:441–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1993.tb01030.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development. 2000;71:543–562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M, Cicchetti D. An ecological-transactional analysis of children and contexts: The longitudinal interplay among child maltreatment, community violence, and children's symptomatology. Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:235–257. doi: 10.1017/s095457949800159x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Coatsworth JD. Competence, resilience, and psychopathology. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology: Vol. 2: Risk, disorder, and adaptation. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1995. pp. 715–752. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Coatsworth JD. The development of competence in favorable and unfavorable environments. American Psychologist. 1998;53:205–220. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard RA. Kids having kids: Economic costs and social consequences of teen pregnancy. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- McGloin JM, Widom CS. Resilience among abused and neglected children grown up. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:1021–1038. doi: 10.1017/s095457940100414x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE E-Risk Study Team. Teen-aged mothers in contemporary Britain. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 2002;43:727–742. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Harrington H, Milne BJ. Males on the life-course-persistent and adolescence-limited antisocial pathways: Follow-up at age 26 years. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14:179–207. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402001104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran PB, Eckenrode J. Protective personality characteristics among adolescent victims of maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1992;16:743–754. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(92)90111-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivan G. Catch-up growth assessment in long-term physically neglected and emotionally abused preschool age male children. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2003;27:103–108. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00513-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repetti RL, Taylor SE, Seeman TE. Risky families: Family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:330–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Cottler L, Bucholz K, Compton W. Diagnostic Interview Schedule for DSM-IV. St. Louis, MO: Washington University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers WH. Regression standard errors in clustered samples. Stata Technical Bulletin. 1993;13:19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Protective factors in children's responses to stress and disadvantage. In: Kent MW, Rolf JE, editors. Primary prevention of psychopathology: Social competence in children. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England; 1979. pp. 49–74. [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ, Bartko WT, Baldwin A, Baldwin C, Seifer R. Family and social influence on the development of child competence. In: Lewis M, Feiring C, editors. Families, risk, and competence. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1998. pp. 161–185. [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ, Chandler MJ. Reproductive risk and the continuum of caretaking casualty. In: Horowitz FD, Hetherington M, Scarr-Salapatek S, Siegal G, editors. Review of child development research. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1975. pp. 187–244. [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ, MacKenzie MJ. Research strategies for capturing transactional models of development: The limits of the possible. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15:613–640. doi: 10.1017/s0954579403000312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ, Seifer R, Baldwin A, Baldwin C. Stability of intelligence from preschool to adolescence: The influence of social and family risk factors. Child Development. 1993;64:80–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277:918–924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattler JM. Assessment of children: WISC-III and WPPSI-R supplement. San Diego, CA: Author; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Scarr S. Developmental theories for the 1990s: Development and individual differences. Child Development. 1992;63:1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedlak AJ, Broadhurst DD. Executive summary of the third national incidence study of child abuse and neglect. 1996 Retrieved July 31, 2002 from http://www.calib.com/nccanch/pubs/statinfo/nis3.cfm#national.