Abstract

Prepulse inhibition of the startle response to auditory stimulation (AS) is a measure of sensorimotor gating that is disrupted by the dopamine D1/D2 receptor agonist, apomorphine. The apomorphine effect on prepulse inhibition is ascribed in part to altered synaptic transmission in the limbic-associated shell and motor-associated core subregions of the nucleus accumbens (Acb). We used electron microscopic immunolabeling of dopamine D1 receptors (D1Rs) in the Acb shell and core to test the hypothesis that region-specific redistribution of D1Rs is a short-term consequence of AS and/or apomorphine administration. Thus, comparisons were made in the Acb of rats sacrificed one hour after receiving a single subcutaneous injection of vehicle (VEH) or apomorphine (APO) alone or in combination with startle-evoking AS (VEH+AS, APO+AS). In both regions of all animals, the D1R immunoreactivity was present in somata and large, as well as small, presumably more distal dendrites and dendritic spines. In the Acb shell, compared with the VEH+AS group, the APO+AS group had more spines containing D1R immunogold particles, and these particles were more prevalent on the plasma membranes. This suggests movement of D1Rs from distal dendrites to the plasma membrane of dendritic spines. Small- and medium-sized dendrites also showed a higher plasmalemmal density of D1R in the Acb shell of the APO+AS group compared with the APO group. In the Acb core, the APO+AS group had a higher plasmalemmal density of D1R in medium-sized dendrites compared with the APO or VEH+AS group. Also in the Acb core, D1R-labeled dendrites were significantly smaller in the VEH+AS group compared to all other groups. These results suggest that alerting stimuli and apomorphine synergistically affect distributions of D1R in Acb shell and core. Thus adaptations in D1R distribution may contribute to sensorimotor gating deficits that can be induced acutely by apomorphine or develop over time in schizophrenia.

Keywords: accumbens shell, immunogold, receptor trafficking, schizophrenia, sensorimotor gating, spine

INTRODUCTION

Prepulse inhibition is an operational measure of sensorimotor gating, where there is a reduction in startle response when auditory (AS) or other startling stimulus (pulse) is immediately preceded by a weak, non-startling stimulus (prepulse) (Hoffman and Searle, 1965; Ison and Hammond, 1971). This PPI is disrupted in schizophrenic patients (Braff et al., 1992; Grillon et al., 1992), and also in rodents when apomorphine, a dopamine D1/D2 receptor agonist, is systemically administered five to ten minutes prior to testing (Davis et al., 1990; Druhan et al., 1998; Geyer and Swerdlow, 1998; Kinney et al., 1999). Thus, the acute administration of apomorphine may elicit adaptation within the sensorimotor systems that mimic those pathologically occurring in schizophrenia.

The PPI-disruptive effect of apomorphine is mediated in part by increased dopamine in the nucleus accumbens (Acb)(Swerdlow et al., 1986; Swerdlow et al., 1990; Swerdlow et al., 1992). The relevant functional sites likely include both the shell and core subregions of the Acb, but they may be differentially affected (Wan et al., 1994; Wan and Swerdlow, 1996). This is suggested by the known anatomical connectivity of each subregion (Voorn et al., 1989; Heimer et al., 1991; Voorn et al., 1994). The Acb shell receives substantial mesolimbic dopaminergic innervation, while the core is functionally similar to the motor-associated dorsal striatum and receives dopaminergic input from the substantia nigra pars compacta (Groenewegen et al., 1999). Experience-dependent limbic inputs also terminate in the Acb shell, while the sensory cortical inputs target the core region that is involved in appetitive instrumental learning and locomotor activity (Heimer et al., 1991; Zahm and Brog, 1992; Kelley et al., 1997; Groenewegen et al., 1999; Smith-Roe and Kelley, 2000; Di Ciano et al., 2001).

Although dopamine D2 receptors (D2Rs) in the Acb play an important role in the regulation of PPI in rats, there are considerable synergistic interactions between dopamine D1 receptor (D1R) and D2R in the sensorimotor gating system (Wan and Swerdlow, 1993; Wan et al., 1996). D1Rs in the Acb are also critically involved in regulating locomotor activity and attentional processes mediated by mesoaccumbal dopamine release (Carey et al., 1998; Schwienbacher et al., 2002; Misener et al., 2004). Furthermore, D1R activation in the striatum facilitates sensorimotor cortical functions (Steiner and Kitai, 2000). Unlike D2Rs, D1Rs are predominantly located in distal dendrites and dendritic spines, which are major sites for synaptic plasticity (Delle Donne et al., 2004; Hara and Pickel, 2005). The surface expression of D1R is not stationary, but dynamically changed by synaptic activity and the availability of D1R agonists (Dumartin et al., 1998; Lamey et al., 2002). Auditory stimulation (AS), such as that used in acoustic startle testing, transiently decreases extracellular dopamine in the Acb (Humby et al., 1996). Moreover, glutamate activation of NMDA receptors that are co-expressed with D1R in many Acb dendrites, can increase D1R plasma membrane insertion, as well as recruitment of D1Rs to dendritic spines (Scott et al., 2002; Pei et al., 2004; Hara and Pickel, 2005). Thus, either apomorphine binding to D1/D2 receptors or AS resulting in decreased dopamine and/or altered activation of glutamatergic inputs to Acb may affect the expression of D1Rs in selective neuronal compartments within the Acb shell and core neurons. To test this hypothesis, we examined the electron microscopic immunocytochemical labeling of D1Rs in the Acb shell and core of normal rats and rats exposed to AS in measures of PPI in the presence or not of apomorphine. The results provide the first ultrastructural evidence that apomorphine and AS synergistically affect the dendritic plasmalemmal distribution of D1Rs preferentially in the Acb shell.

METHODS

Animal preparation

The animal protocols in this study strictly adhered to NIH guidelines concerning the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals in Research, and were approved by the Animal Care Committee at Weill Medical College of Cornell University. Adult male Sprague Dawley rats (280-350 g; Taconic Farms, Germantown, NY) arrived 14 days prior to their experimental use. All rats were housed two per cage under a 12 hour light/dark cycle. Food and water were available ad libitum.

Apomorphine (R-(−)-Apomorphine-HCL, ICN Biomedicals Inc., Aurora, OH) was dissolved in the vehicle solution (0.9% saline and 0.1 mg/ml ascorbic acid) using a sonicator. The apomorphine solution was injected subcutaneously at 1 mg/kg. This dose was chosen based on previous studies showing that apomorphine injected at the same range of doses disrupts PPI to acoustic startle (Mansbach et al., 1988). The vehicle solution alone was used as a control.

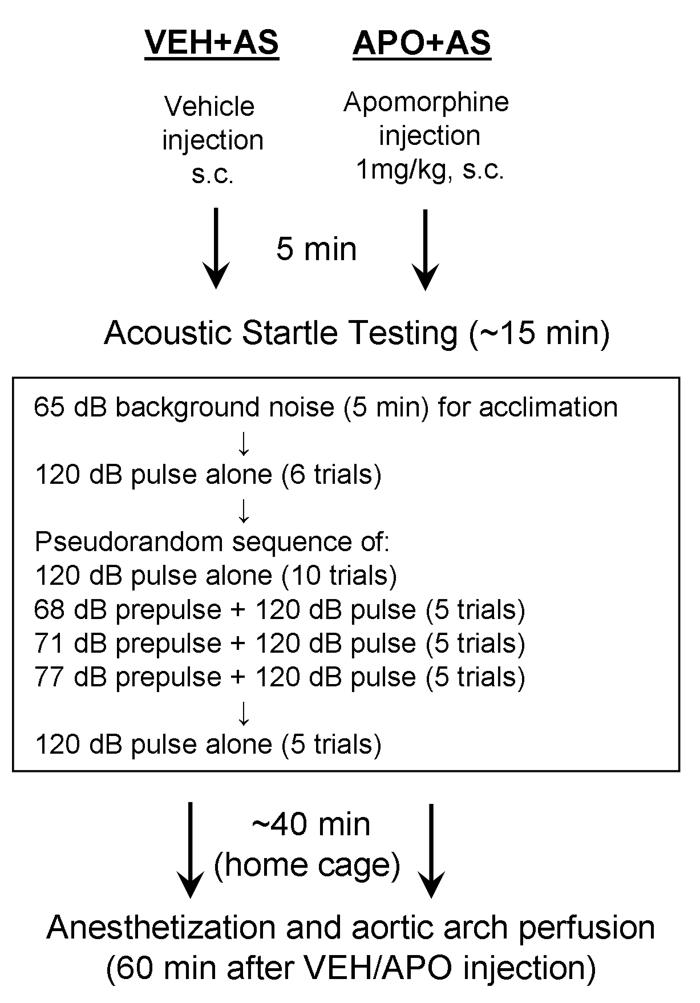

Four groups of 3 rats/group were examined in this study: single subcutaneous injection of 1) vehicle without AS (VEH), 2) apomorphine without AS (APO), 3) vehicle followed by auditory stimulation from acoustic startle testing (VEH+AS), and 4) apomorphine followed by auditory stimulation from acoustic startle testing (APO+AS). Rats in VEH+AS and APO+AS groups received the vehicle or apomorphine injection five minutes before introduction to the acoustic startle chamber and exactly an hour before aortic arch perfusion (Fig 1). The rats in VEH and APO groups also received the injection an hour before perfusion.

Figure 1.

A schematic diagram of the experimental paradigm for VEH+AS and APO+AS groups. Five minutes after the rats received either a vehicle or apomorphine subcutaneous injection, they were introduced to the acoustic startle apparatus. The startle testing started with 5 minutes of 65 dB background noise to allow the rats to acclimate to the environment. Then they were given six 120 dB pulse alone trials followed by a pseudorandom sequence of pulse alone trials and prepulse+pulse trials. The session concluded with an additional five pulse alone trials. After the completion of acoustic startle testing, the VEH+AS and APO+AS rats were returned to their home cage for approximately 40 minutes until the perfusion (60 minutes after the vehicle/apomorphine injection). The VEH and APO groups also received a single subcutaneous injection of vehicle and apomorphine, respectively, but did not undergo acoustic startle testing and remained in their home cage for 60 minutes until the perfusion (not shown).

Acoustic startle testing

All test sessions were performed in a one chamber SR-LAB startle apparatus with digitalized signal output (San Diego Instruments, San Diego, CA). The startle apparatus consisted of 1) a transparent acrylic cylinder 8.2 cm in diameter to hold the rat, 2) Radioshack Supertweeter mounted inside the isolation cabinet to generate the background noise and acoustic stimuli (prepulse and pulse), and 3) microcomputer and interface assembly (San Diego Instruments) to measure and record the startle magnitude as transduced by cylinder movement via a piezoelectric device mounted below a Plexiglass stand. The acoustic startle amplitude was defined as the peak of an average of 250 readings collected every 1 msec beginning at the onset of the acoustic stimulus. Sound levels were measured and calibrated with a Radioshack digital sound level meter (Radioshack Corporation, Fort Worth, TX).

To reduce variation in behavioral results arising from stress, all rats were handled for 10 minutes daily starting on the day of shipment arrival until the day of acoustic startle testing two weeks later. All rats that underwent the acoustic startle evaluation were tested in the light cycle (Weiss et al., 1999). Seven days prior to acoustic startle testing, the rats were exposed to a brief matching startle session, a procedure that is commonly used to reduce group variability in responses (Geyer and Swerdlow, 1998; Pothuizen et al., 2005). For this, rats were placed in the startle chamber and exposed to 65 dB background noise for 5 minutes, followed by 11 pulses, each consisting of 40 msec bursts of 120 dB noise, with inter-trial intervals averaging 15 seconds (range 8 to 23 seconds). The peak and average responses from each rat on each of the 11 trials were collected, and the initial response value was recorded separately from the remaining ten responses for each rat, the latter of which were averaged together. Data from these sessions were used to divide the rats into two groups (VEH+AS and APO+AS) with similar mean and variance of basal startle amplitudes.

On the day of the acoustic startle and PPI evaluation, each rat received a subcutaneous vehicle or apomorphine injection. The rats in VEH+AS and APO+AS groups were introduced into the acrylic cylinder 5 minutes after the injection. The acoustic startle testing started with 5 minutes of 65 dB background noise to allow the rats to acclimate to the environment. The first six trials were pulse alone trials, which consisted of a 40 msec burst of 120 dB noise. Then a pseudorandom sequence of pulse alone trials and prepulse+pulse trials were presented at inter-trial intervals averaging 15 seconds (range 8 to 23 seconds). The pulse alone trial was presented ten times, and the three different prepulse+pulse trial types were each presented five times. These consisted of a 20 msec prepulse stimuli (3, 6 or 12 dB above the 65 dB background noise), which do not elicit motor responses, preceding the 120 dB pulse by 100 msec. The session concluded with an additional five pulse alone trials. The acoustic startle testing lasted approximately 15 minutes. The VEH and APO rats were returned to their home cages for one hour after the apomorphine or vehicle injection. The VEH+AS and APO+AS rats were returned to their home cages for approximately 40 minutes after the end of the acoustic startle testing.

Differences in startle amplitudes between groups were statistically evaluated using analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's post-hoc test with SPSS (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL.). Results are expressed as means ± s.e. of the mean. Only probability values (p) less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Tissue preparation

All rats were deeply anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (100 mg/kg, i.p.) an hour after vehicle or apomorphine injection. We chose this time point as one that would enable not only internalization, but also recycling, and lateral movement of D1R (Vargas and von Zastrow, 2004; Scott et al., 2006). A longer time point would be more likely to evoke changes in gene expression. The rats were perfused via the ascending aorta first with 10 ml of heparin (1000 U/ml), then with 60 ml of 3.75% acrolein and 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB; pH 7.4), followed by 200 ml of 2% PFA in 0.1 M PB. The brains were removed and postfixed with 2% PFA in 0.1 M PB for 30 minutes at 4°C, and then cut coronally into 40 μm sections on a Vibratome (Leica, Deerfield, IL). Holes were punched at different locations within the cortex to distinguish between rats of different treatment groups. All Acb sections used for this study were selected at 1.60 mm anterior to Bregma (Paxinos and Watson, 1986) and contained both the shell and the core. These sections were placed in 1% sodium borohydride in 0.1 M PB for 30 minutes to remove excess aldehydes, and then rinsed thoroughly with 0.1 M PB. To enhance the penetration of immunoreagents, the sections were incubated in a cryprotectant solution (25% sucrose and 3.5% glycerol in 0.05 M PB) for 15 minutes and rapidly freeze-thawed by immersing in liquid chlorodifluoromethane (Freon, Refron Inc., NY) followed by liquid nitrogen and finally in room temperature 0.1 M PB. The sections were then rinsed in 0.1 M Tris-buffered saline (TBS).

Antibody

A rat monoclonal antibody raised against a 97 amino acid peptide corresponding to the C-terminus of the human D1R was obtained commercially (Clone 1-1-F11 S.E6, Sigma RBI, Saint Louis, MO). The D1R antibody has been well characterized and shown to specifically recognize the antigenic peptide by Western blot, immunoprecipitation and blocking control experiments used for immunocytochemistry (Levey et al., 1993). This D1R antibody has also been localized by electron microscopic immunocytochemistry in the Acb shell and core (Hara and Pickel, 2005; Hara et al., 2006). To determine the level of non-specific attachment of the primary antibody or secondary gold-conjugated IgGs, we examined the number of immunogold particles overlying myelin, where D1R is not known to be expressed.

Immunocytochemical labeling

The free-floating sections were incubated in 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in 0.1 M TBS, pH 7.6, for 30 minutes to block non-specific binding of antisera. Then the sections were incubated for 48 hours at 4°C in the primary antibody solution, which consisted of the rat monoclonal anti-D1R (1:100 dilution) with 0.1% BSA in 0.1 M TBS.

For immunogold-silver labeling, the sections were rinsed in 0.01 M PBS, pH 7.4, blocked in 0.8% BSA and 0.1% gelatin in PBS for 10 minutes, and subsequently incubated for 2 hours in a 1:50 dilution of goat anti-rat (for D1R immunogold) IgG conjugated with 1 nm colloidal gold (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL). The sections were rinsed several times with 0.1 M TBS, then placed in 2% glutaraldehyde for 10 minutes to ensure adherence of the secondary gold-conjugated IgG to the sections (Chan et al., 1990). The gold particles were silver-enhanced using the IntenS-EM kit (Amersham) for 7 minutes at room temperature. The sections were fixed in 2% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 M PB for 60 minutes, followed by dehydration with a graded series of ethanols and propylene oxide. These sections were incubated overnight in 1:1 mixture of propylene oxide and Epon (Electron Microscopy Science, Fort Washington, PA). The sections were transferred to 100% Epon for 2-3 hours and flat-embedded between sheets of Aclar plastic. Flat-embedded sections were examined with a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope (Nikon Instruments Inc., Melville, NY) and images were captured using a Micropublisher 5.0RTV camera (QImaging, BC, Canada). Light microscopic images were adjusted for brightness and sharpness using Adobe Photoshop (version 7.0.1, Adobe Systems Inc., Mountain View, CA) and then imported into PowerPoint, Microsoft Office, 2003.

Areas containing both the Acb shell and core, immediately medial to the anterior commissure, were trimmed into trapezoids (Fig. 2) and cut into ultra-thin (60 nm) sections with a diamond knife (Diatome, Fort Washington, PA) using an ultratome (NOVA LKV-Productor AB, Bromma, Sweden). Thin sections from the outer surface of the tissue were collected on 400-mesh copper grids (Electron Microscopy Sciences). These sections were counterstained with 5% uranyl acetate for 20 minutes followed by Reynold's lead citrate (Reynolds, 1963) for 5 minutes. After washing and drying, the ultra-thin sections were examined at 60 kV with a Philips CM10 transmission electron microscope (FEI, Hillsboro, OR). The microscopic images were captured using AMT Advantage HR/HR-B CCD Camera System (Advanced Microscopy Techniques, Danvers, MA).

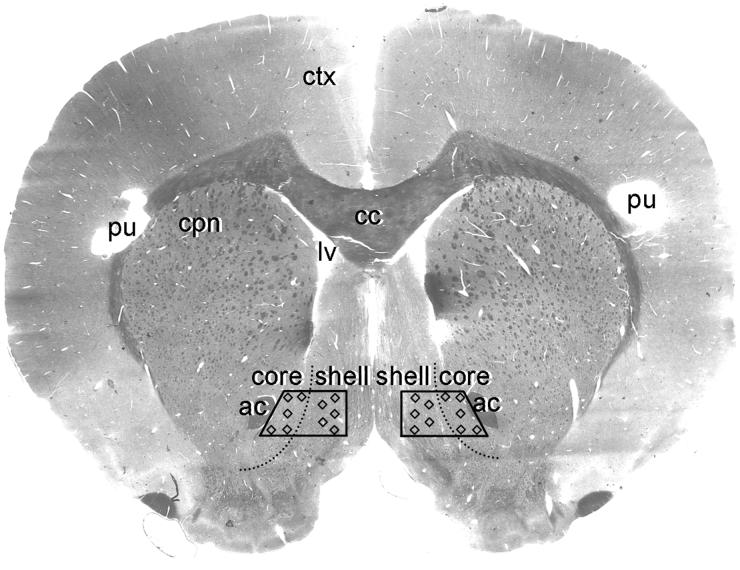

Figure 2.

A light micrograph of a flat-embedded accumbens vibratome section labeled with D1R. The trapezoids indicate the locations from which the ultrathin sections were collected for electron microscopic image analysis. Each trapezoid included both the Acb shell and core, directly medial to the anterior commissure (ac) at the level 1.6 mm anterior to Bregma (Paxinos and Watson, 1986). Microscopic images were taken from 18-20 grid squares within the two Acb trapezoids per rat, illustrated by the small squares. None of these grid squares were adjacent to one another in order to collect a representative sample from a vast area of the medial Acb shell and core. Holes were punched (pu) at different locations within the cortex (ctx) to distinguish between rats in different experimental groups. cc, corpus callosum; cpn, caudate-putamen nucleus; lv, lateral ventricle.

Electron microscopic analysis

Data analysis on D1R immunolabeling was performed on ultra-thin sections collected near the surface of the tissue at the interface with the embedding material. All the sections from each of the four experimental groups were co-processed and the identical sampling methods were used, thus eliminating variables that could affect between-group comparisons. The profiles containing D1R immunoreactivity were classified using descriptions from Peters et al. (1991). The dendritic profiles were characterized by abundant organelles such as mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum and frequent contacts from vesicle-filled axon terminals. A profile was considered as a dendritic spine when smaller than 0.5 μm in diameter, largely devoid of organelles and receptive to an asymmetric excitatory-type synapse. Profiles were considered to be selectively immunogold-labeled even when they contained only one gold particle to avoid false negative labeling of smaller profiles. This approach of immunogold quantification was validated because the distance between two D1R immunogold particles within longitudinally-cut dendritic profiles was significantly larger than the thickness of the thin-sections (Hara et al., 2006).

Two accumbens vibratome sections containing both the shell and core subregions as shown in Figure 2 were examined from each of twelve rats. For every rat, microscopic images were taken from 18-20 grid squares illustrated by the small squares within the two Acb trapezoids (Fig. 2). None of these grid squares were adjacent to one another. This assumed the collection of a representative sample from a vast area of the medial Acb shell and core. A micrograph was captured when there were at least 2 transversely-cut D1R-labeled dendritic profiles within the camera field at 13,500X magnification (41.0 μm2) to select areas where there was optimal antibody penetration. We specifically looked for transversely-cut D1R-labeled profiles to exclude longitudinally-cut dendrites with high plasma membrane to surface area ratios. At least 80 micrographs at this magnification were obtained from each rat and each subregion. Approximately 600 labeled dendritic profiles in each experimental group and each subregion were quantified (4788 dendritic profiles in total). D1R immunogold particles were categorized with respect to whether they were in contact with the plasma membrane or present in the cytoplasm. The gold particles were almost always inside the plasma membrane, consistent with the generation of the antibody against the intracellular C-terminus. When more than half of the gold particle was inside the plasma membrane, it was considered as plasmalemmal dendritic labeling and not labeling of an adjacent process, such as an axon terminal or glia. In rare cases, when more than 50% of the gold particle was outside the membrane, this particle was not counted as dendritic labeling. The number of D1R-labeled dendrites determined using these criteria parallels that seen with immunoperoxidase labeling in the Acb (Hara and Pickel, 2005). Two or more gold particles next to each other, but without defined boundaries, were counted as one particle. All microscopy and quantification of labeled profiles were applied equally in all sections and performed blind.

MCID Elite software (version 6.0, Imaging Research Inc., Ontario, Canada) was used to measure the cross-sectional diameters, perimeters, surface areas and form factors of all D1R-labeled dendritic profiles in the Acb shell and core. The diameter, perimeter and surface areas were all used as indirect measures of dendritic size. Only transversely-cut D1R-labeled dendrites with a form factor of over 0.50 were included in our data to exclude longitudinally-cut dendrites with high plasma membrane to surface area ratios. The parameters used for statistical comparisons were: 1) the number of D1R-labeled spines/unit neuropil area, 2) the number of plasmalemmal D1R gold particles on spines/unit neuropil area, 3) the total number of spines (D1R-labeled and unlabeled, combined)/unit neuropil area, 4) the number of plasmalemmal D1R gold particles on a dendritic profile/dendritic perimeter, 5) the number of cytoplasmic D1R gold particles on a dendritic profile/dendritic cross-sectional area, 6) the number of total D1R gold particles in a dendritic profile/dendritic cross-sectional area, and 7) the cross-sectional surface area of a D1R-labeled profile.

Cluster analysis by dendritic diameter was performed to statistically divide all D1R-labeled dendrites into small, medium and large subcategories using SPSS (SPSS Inc.) in order to compare similar structures across groups. For statistical evaluation, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's post hoc test in SPSS (SPSS Inc.) was used for comparisons between the four experimental groups of rats. Observed power was calculated with each analysis to confirm that the sample size was sufficient to support the data.

For preparation of microscopic illustrations, Adobe Photoshop software (version 7.0.1, Adobe Systems Inc., Mountain View, CA) was used to enhance contrast and sharpness of the digital images. These images were then imported into PowerPoint, Microsoft Office, 2003 to make composite plates and add lettering.

RESULTS

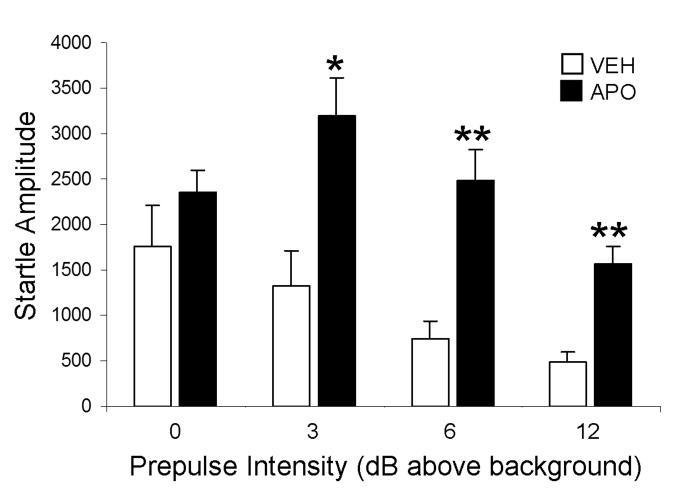

The behavioral testing showed that acute apomorphine effectively disrupts PPI to AS. When a prepulse (3, 6, 12 dB above background) preceded the 120 dB pulse AS, the apomorphine-injected rats had significantly greater startle responses than the vehicle-injected rats, resulting in disruption of PPI (p=0.030, 0.0015 and 0.0001, respectively; Fig 3). In the absence of prepulse (0 dB above background), the vehicle-and apomorphine-injected rats showed no statistically significant differences in the startle amplitudes to the 120 dB AS (p>0.05; Fig 3).

Figure 3.

A bar graph showing the maximal startle amplitude in vehicle (VEH)- and apomorphine (APO)- injected rats in response to 120 dB pulse alone (0) and prepulse (3, 6, 12db above background) plus 120 dB pulse. A two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test was used for statistical comparisons between the vehicle and apomorphine-injected rats. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, n=3 rats/experimental group

Electron microscopy showed that D1R distribution seen in the VEH group was similar to that of naïve rats of the same strain from a previous study, even though these particles were not quantitatively compared (Hara and Pickel, 2005). It also showed treatment-specific differences in D1R dendritic distributions in rats receiving apomorphine and/or AS. D1R gold particles over myelin and other structures not known to express D1Rs were rare in the Acb. Only one out of 432 myelinated axons showed a single D1R gold particle in 9316 μm2 of neuropil. Therefore, background immunolabeling was negligible (<0.25%), making it unlikely that non-specific attachment of the gold particles affected the between-group comparisons of D1R distributions.

The D1R immunogold particles were often located on the plasmalemma, but also present near intracellular endomembranous structures in dendritic spines as well as dendrites, somata and axons of the Acb shell and core of control rats. Quantitative comparisons of immunogold labeling showed significant region-specific differences between control and experimental groups that relate to D1R locations in dendritic profiles of Acb shell and core.

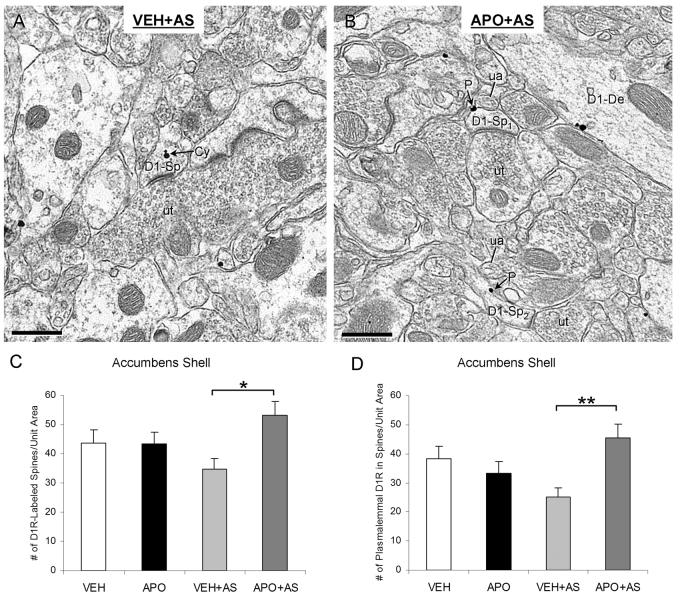

Apomorphine-induced changes in spine distribution of D1Rs in rats receiving AS

The spine distributions of D1R labeling were quantitatively compared between the four groups of rats. In the Acb shell, compared with the VEH+AS group, the APO+AS group showed significantly more D1R-labeled spines per unit area (F(3, 972)=3.05; p=0.014; observed power, 0.717), as well as a higher number of D1R gold particles on the plasmalemma of spines (F(3, 972)=4.27; p=0.003; observed power, 0.864; Fig. 4A-D). These changes were not accompanied by a difference in the total number of spines (D1R-labeled and unlabeled combined; p>0.05). There were no statistically significant differences in any of the criteria between VEH and APO in absence of AS in the shell (p>0.05). In the Acb shell of APO+AS rats, the D1R gold particles were often located on spine necks or heads, away from the excitatory synapses (Fig. 4B). Many of these plasmalemmal gold particles were present near or apposed to small unlabeled axonal profiles (Fig. 4B). In the Acb core, no significant differences were observed in the number of D1R-labeled spines, plasmalemmal D1Rs in dendritic spines, or total number of spines between any of the four treatment groups (p>0.05; Fig. 5).

Figure 4.

Apomorphine effects on D1R immunogold distributions in dendritic spines of the Acb shell in rats exposed to acoustic startle. (A, B) Electron micrographs showing spine heads (D1-Sp) with D1R immunogold particles in the cytoplasm (Cy) and on the plasma membrane (P) in VEH+AS group (A) and APO+AS group (B), respectively. The spines receive asymmetric excitatory-type synapse from unlabeled terminals (ut). In the APO+AS group, D1R immunogold particles are also present on the plasmalemma of a spine neck (D1-Sp2) and on the plasma membrane of a dendrite (D1-De). The plasmalemmal D1R immunogold particles are located near unlabeled small axonal profiles (ua). (C, D) Bar graphs showing the number of D1R-labeled spines (C) and the number of D1R gold particles on the plasma membrane of spines (D) per 4100 μm2 of Acb shell tissue. A one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test was used for statistical comparisons between the following groups: vehicle-injected (VEH), apomorphine-injected (APO), vehicle injection followed by auditory stimulation (VEH+AS) and apomorphine injection followed by auditory stimulation (APO+AS). *p<0.05, **p<0.01. n=3 rats/each of the four experimental groups

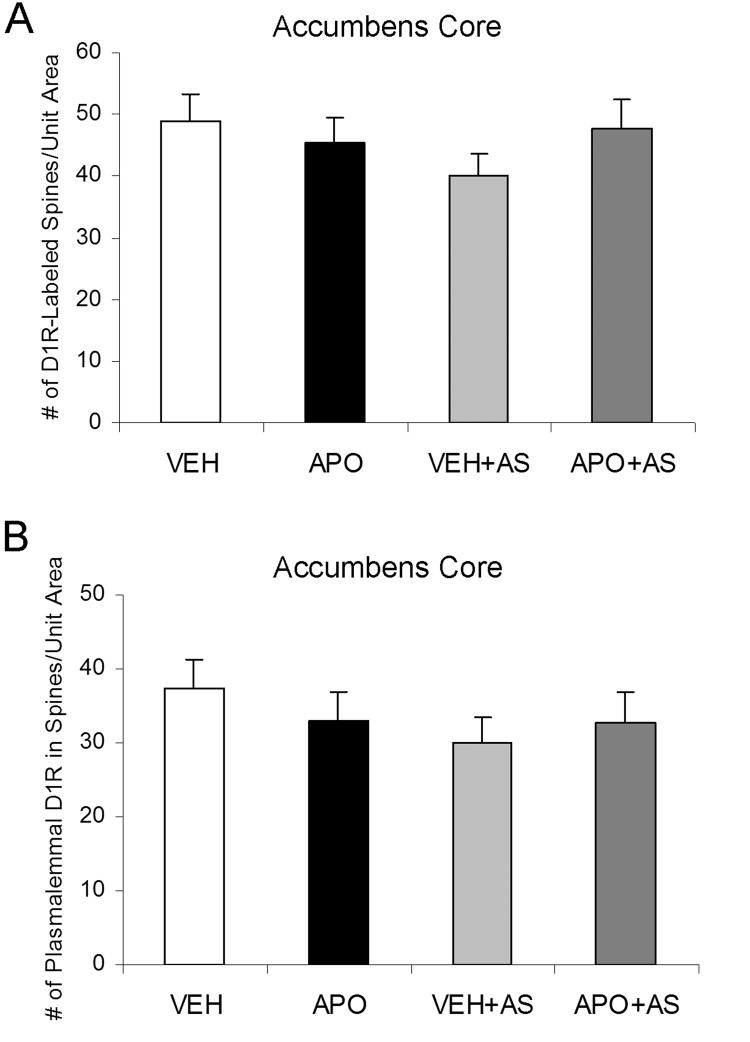

Figure 5.

Bar graphs showing the between-group similarities in the numbers of D1R-labeled spines (A) and the numbers of D1R gold particles on the plasma membrane of spines (B) per 4100 μm2 of Acb core tissue. A one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test was used for statistical comparisons between the following groups: vehicle-injected (VEH), apomorphine-injected (APO), vehicle injection followed by auditory stimulation (VEH+AS) and apomorphine injection followed by auditory stimulation (APO+AS). No statistically significant differences were observed between any of the groups. n=3 rats/each of the four experimental groups

Size-dependent dendritic distributions of D1Rs in the Acb shell

D1R-labeled dendrites had diameters that ranged from 0.01 to 2.03 μm. The larger dendrites contained abundant endoplasmic reticulum and other organelles similar to the somata. These dendrites also showed considerably more cytoplasmic D1R labeling than the smaller, presumably more distal dendrites, regardless of the Acb region or treatment conditions. Thus, cluster analysis by dendritic diameter was used to statistically divide all D1R-labeled dendrites into small, medium and large subcategories in order to compare similar structures across groups. Small dendrites were often contiguous with dendritic spines and not clearly distinguished from the spines. This also suggests that the small dendrites are more distal on the dendritic tree. Most of the small D1R-labeled dendrites and dendritic spines received excitatory-type asymmetric synapses.

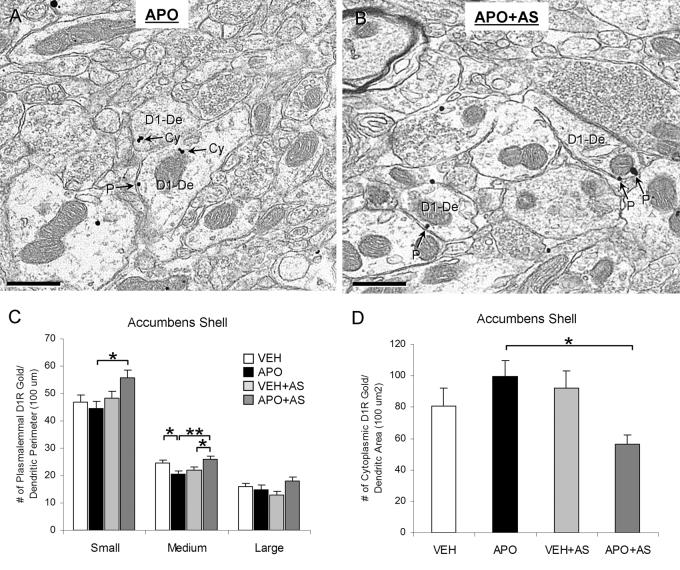

In small (diameters ranging from 0.11-0.49 μm) dendrites of Acb shell, the APO+AS group had a significantly higher number of plasmalemmal D1R gold particles per unit perimeter length compared to the APO group (F(3, 788)=3.17; p=0.017; observed power, 0.735; Fig 6A-C]. D1R gold particles were usually seen on portions of the plasmalemma apposed by other dendritic, axonal, or glial profiles and were rarely present on the asymmetric synapses (Fig 6A, B). In medium (0.50-0.87 μm in diameter) dendrites, the APO group showed a significantly lower plasmalemmal D1R gold density compared to the VEH group (p=0.035), but this difference was reversed when AS followed the apomorphine administration (F(3, 1154)=5.42; p=0.002; observed power, 0.937; Fig 6C). The APO+AS group also had a significantly higher plasmalemmal D1R density compared with the VEH+AS group (p=0.039). There were no statistically significant differences in the D1R plasmalemmal distribution between any of the groups in the Acb shell large (0.88-1.86 μm in diameter, n=480) dendrites. When dendrites of all sizes were combined, the APO+AS group had a significantly lower number of cytoplasmic D1R gold particles per dendritic cross-sectional area compared to the APO group (F(3, 2422)=3.73; p=0.010; observed power, 0.811; Fig 6D).

Figure 6.

Size- and treatment-dependent differences in plasmalemmal and cytoplasmic D1R labeling in the Acb shell dendrites. (A, B) Electron micrographs showing differences in D1R immunogold distributions in small-medium dendrites (D1-De) between the APO (A) and APO+AS (B) groups. In the APO group, one dendrite contains D1R immunogold particles only in the cytoplasm (Cy) and the other dendrite contains both cytoplasmic and plasmalemmal (P) D1R gold particles. In the APO+AS group, the D1R immunogold particles in both dendrites are located on the plasma membrane (P). (C) A bar graph showing the number of plasmalemmal D1R immunogold particles per unit perimeter length (100 μm) in each experimental group and each size of Acb shell dendrites. Cluster analysis by dendritic diameter was performed to statistically divide the D1R-labeled dendrites into small, medium and large subcategories. A one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test was used for statistical comparisons between the following groups: vehicle-injected (VEH), apomorphine-injected (APO), vehicle injection followed by auditory stimulation (VEH+AS) and apomorphine injection followed by auditory stimulation (APO+AS). *p<0.05, **p<0.01, n=3 rats/each of the four experimental groups. (D) A bar graph showing the number of cytoplasmic D1R immunogold particles per unit dendritic cross-sectional area (100 um2) in the four experimental groups. A one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test was used for statistical comparisons between the groups. *p<0.05, n=3 rats/each of the four experimental groups

The average dendritic cross-sectional area of all transversely-cut D1R-labeled dendrites in the Acb shell was smaller in the VEH+AS group compared to the VEH group (F(3, 2422)=3.281; p=0.022; observed power, 0.753). There were, however, no between-group differences in the dendritic diameter, which is another measure of dendritic size (p>0.05). There were also no between-group differences observed in the total number of D1R immunogold particles per cross-sectional area of D1R-labeled dendrites in the Acb shell (p>0.05).

Size-dependent dendritic distribution of D1Rs in the Acb core

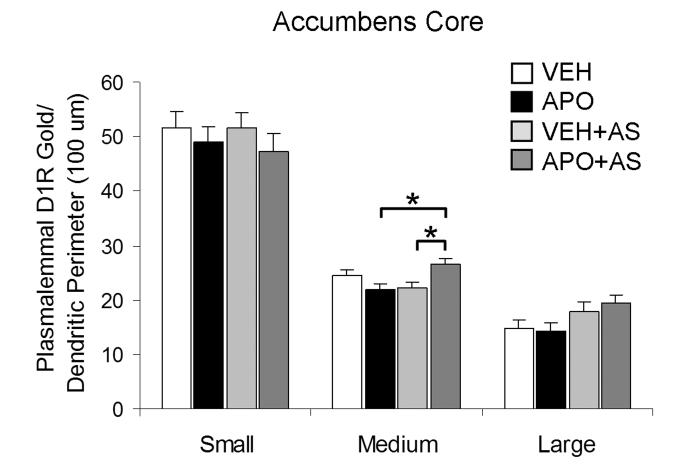

Cluster analysis by dendritic diameter was used to statistically divide all Acb core D1R-labeled dendrites into small, medium and large subcategories as performed in the Acb shell. In the medium (0.44-0.78 μm in diameter) dendrites of the Acb core, the APO+AS group had a significantly higher plasmalemmal D1R gold density compared to the APO group and the VEH+AS group (F(3, 1247)=3.855; p=0.017 and 0.027, respectively; observed power, 0.824; Fig 7). There were no statistically significant between-group differences in the D1R plasmalemmal density in the Acb core small (0.01-0.43 μm in diameter, n=708) or large (0.79-2.03 μm in diameter, n=411) dendrites (p>0.05).

Figure 7.

A bar graph showing an effect of apomorphine and auditory stimulation in the number of plasmalemmal D1R immunogold particles per unit perimeter length (100 μm), exclusively in medium-sized dendrites of the Acb core. Cluster analysis by dendritic diameter was performed to statistically divide the D1R-labeled dendrites into small, medium and large subcategories. A one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test was used for statistical comparisons between the following groups: vehicle-injected (VEH), apomorphine-injected (APO), vehicle injection followed by auditory stimulation (VEH+AS) and apomorphine injection followed by auditory stimulation (APO+AS). *p<0.05, n=3 rats/each of the four experimental groups

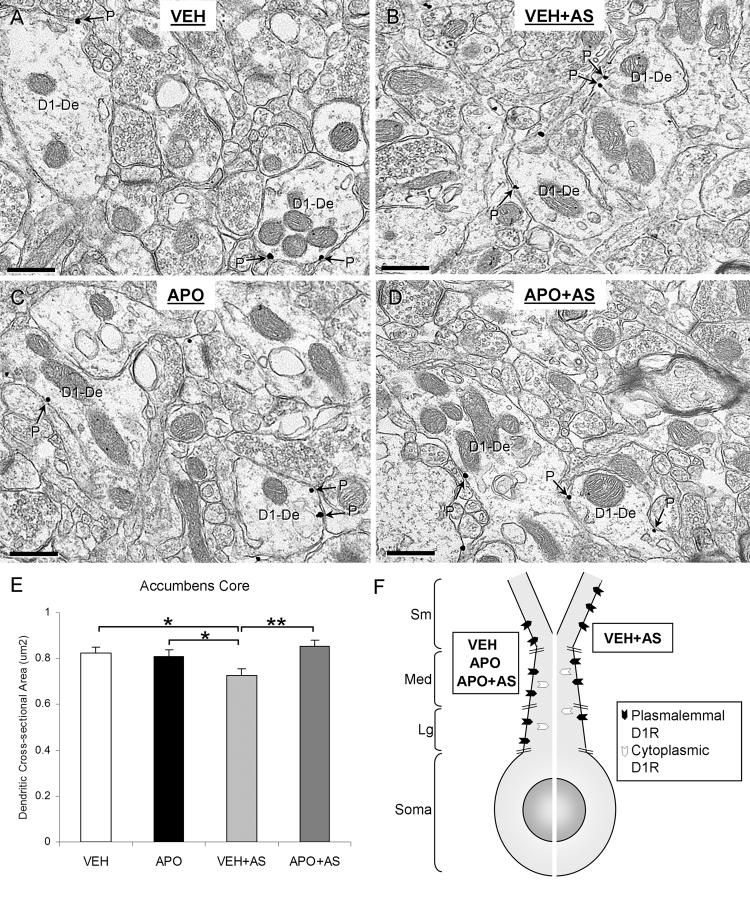

In the Acb core, the average cross-sectional area of all transversely-cut D1R-labeled dendrites was significantly smaller in the VEH+AS group compared to the VEH group, APO group and the APO+AS group (F(3, 2366)=3.822; p=0.011, 0.033, and 0.008, respectively; observed power, 0.821; Fig 8A-F). The average diameter of D1R-labeled dendrites was also significantly smaller in the VEH+AS group compared to the APO+AS group in the Acb core (F(3, 2366)=2.917; p=0.017; observed power, 0.697). There were no between-group differences observed in the total number of D1R immunogold particles per cross-sectional area of D1R-labeled dendrites in the Acb core (p>0.05).

Figure 8.

Targeting D1Rs to smaller dendrites of Acb core in rats exposed to vehicle injection and auditory stimulation (VEH+AS) compared with rats receiving a vehicle injection alone (VEH), an apomorphine injection alone (APO) or an apomorphine injection followed by auditory stimulation (APO+AS). (A-D) Electron micrographs showing D1R-labeled dendrites (D1-De) in each of the four groups (VEH, APO, VEH+AS, APO+AS). The D1R immunogold particles are located on the plasma membrane (P) of the dendrites in all groups. The D1R-labeled dendrites in the VEH+AS group are smaller in size (B) than those in all other groups (A, C, D). (E) A bar graph showing the average cross-sectional area (μm2) of Acb core D1R-labeled dendrites in each experimental group. A one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test was used for statistical comparisons between the following groups: VEH, APO, VEH+AS, and APO+AS. *p<0.05, **p<0.01; n=3 rats/each of the four experimental groups. (F) A schematic diagram showing the D1Rs targeted to smaller, presumably more distal dendrites in the VEH+AS group compared to VEH, APO and APO+AS groups in the Acb core. Sm, small dendrite; Med, medium dendrite; Lg, large dendrite.

DISCUSSION

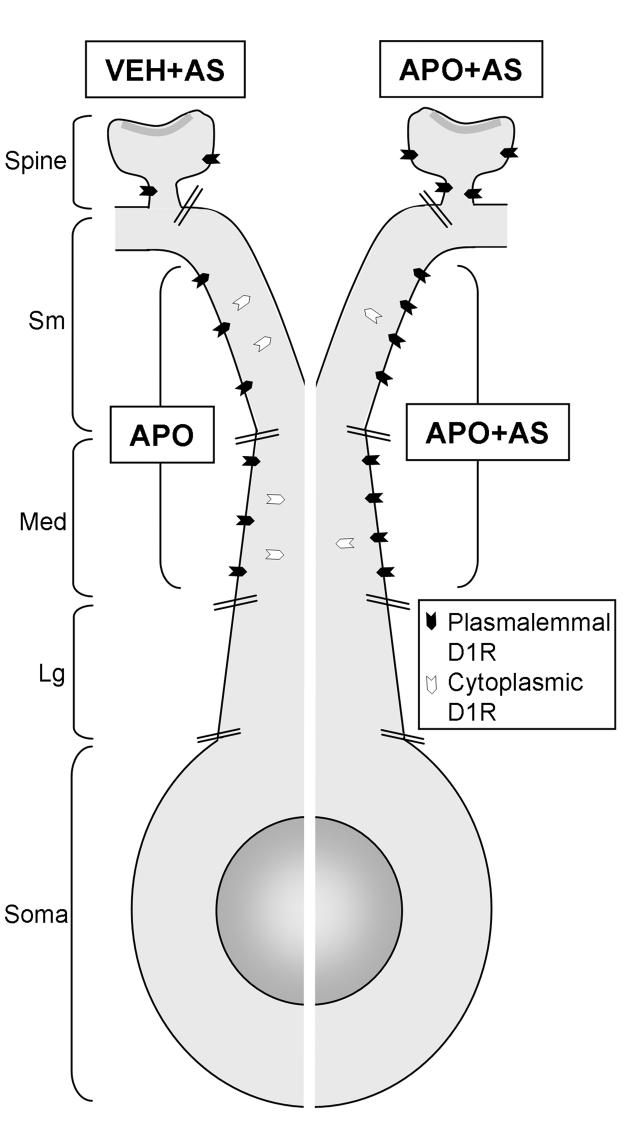

Our results provide the first ultrastructural evidence that apomorphine and AS synergistically affect dendritic D1R subcellular distribution in a size- and subregion-specific manner in the rat Acb. The greatest changes in D1R distributions were seen in dendrites and dendritic spines of the Acb shell as summarized in Figure 9. These changes as well as more minor adaptations in D1R dendritic location in the Acb core implicate D1R trafficking in the Acb in response to alerting stimuli that are potently affected by dopamine. These findings are discussed with respect to their contribution to understanding the sensorimotor gating deficits seen in schizophrenia.

Figure 9.

A schematic diagram showing the soma and dendrites of a spiny neuron in Acb shell. The relative plasmalemmal/cytoplasmic densities of D1R gold particles in dendritic compartments (dendritic spine, small (Sm)-, medium (Med)-, and large (Lg)-sized dendrites) are shown. The neuron is artificially divided (white line) so as to compare experimental groups. These groups received a vehicle injection followed by auditory stimulation (VEH+AS), an apomorphine injection alone (APO), or an apomorphine injection followed by auditory stimulation (APO+AS). In spines, the APO+AS group has significantly more plasmalemmal D1Rs compared to the VEH+AS group. In small and medium dendrites, the APO+AS group has significantly more D1Rs on the plasma membrane compared to the APO group. The greater density of plasmalemmal D1R particles in the APO+AS group is paralleled by a decrease in cytoplasmic D1Rs, suggesting surface trafficking from a cytoplasmic reserve pool.

Methodological Considerations

Our results establish the feasibility of electron microscopic pre-embedding immunogold for determining acute changes in D1R distributions across experimental groups and brain regions. The D1R antibody used in this study is well characterized by Western blot, immunoprecipitation and blocking control experiments and shows high specificities in the Acb and other brain areas known to express D1Rs (Weiner et al., 1991; Levey et al., 1993; Lu et al., 1998). Moreover, the normal localization of D1Rs in our control group (VEH) matched previous light and electron microscopic immunocytochemical studies using the same antibody (Hara and Pickel, 2005).

The immunogold quantification methods used for between-group comparisons were similar to those used in other studies (Glass et al., 2005; Lessard and Pickel, 2005). All the sections from each of the four experimental groups were co-processed, and special care was taken to use identical sampling methods. Micrographs were collected from many grid squares throughout the medial Acb shell and core to eliminate the possibility of biasing the data. Quantitative data analysis of D1R immunogold labeling was performed exclusively on ultra-thin sections collected near the surface of the tissue at the interface with the embedding material, where there was optimal penetration of primary and secondary antisera. Profiles were considered as D1R-labeled when they contained even one gold particle, since background labeling over myelin and other structures not known to express D1Rs was negligible. This method of quantifying profiles with one or more gold particles has been used when characterizing other receptors in the Acb (Pickel et al., 2004; Hara and Pickel, 2005). The observed level of background suggests that this approach yielded <0.25% error, making it unlikely that non-specific attachment of gold particles affected the between-group comparisons of D1R distributions. Any variable that could affect D1R subcellular distribution was expected to affect all experimental groups equally.

The acoustic startle testing consisted of both high and low intensity AS. The changes in D1R distributions in rats receiving AS are most likely due to the high intensity AS (120 dB pulse), and not the low intensity prepulses, since prepulses themselves do not elicit motor responses (Hoffman and Searle, 1965; Swerdlow et al., 2002). Furthermore, high intensity pulses, when presented alone, produce a significant decrease in extracellular dopamine levels in the Acb, but this change is inhibited when a prepulse precedes the pulse (Humby et al., 1996). In parallel studies of neurokinin 1 receptor distributions in the ventral tegmental area also showed that AS-evoked relocation of these receptors was not affected by the presence or absence of prepulses in the acoustic startle testing (Lessard and Pickel, 2005).

Apomorphine- and AS-induced changes in D1R distribution in the Acb shell

In dendritic spines of Acb shell, the APO+AS group had a significantly greater plasmalemmal density of D1R immunogold particles than the VEH+AS group. D1R immunogold particles in the APO+AS group were often located on extrasynaptic plasma membranes of spine necks. These are strategic locations for D1Rs, since dopaminergic terminals preferentially contact dendritic spine necks (Sesack and Pickel, 1990; Groves et al., 1994). Accordingly, many D1R immunogold particles on spine necks were apposed by small unlabeled axonal profiles, characteristic of dopaminergic terminals (Groves et al., 1994; Pickel et al., 1996). The APO+AS group also had a significantly higher number of D1R-labeled spines compared to the VEH+AS group, without a significant change in the total (labeled and unlabeled) number of spines. Our results suggest that the combination of apomorphine and AS may induce movement of D1Rs from distal dendrites to dendritic spine plasmalemma. In addition, D1Rs in the spine cytoplasm may be transferred to the spine plasma membrane.

The APO+AS group also had a greater plasmalemmal density of D1R immunogold particles in small and medium dendrites compared to the APO group. The plasmalemmal increase was paralleled by a corresponding decrease in cytoplasmic D1R gold particles in the APO+AS group, with no change in the total dendritic gold particles (Fig. 9). This suggests that in the APO+AS group, the cytoplasmic D1Rs in the Acb shell small and medium dendrites are being mobilized to the plasma membrane.

The greater number of D1R-labeled spines and higher plasmalemmal density of D1Rs in small/medium dendrites and dendritic spines of the APO+AS group as compared with other control groups may be a compensatory response to a presumable decrease of extracellular dopamine. The high intensity AS used in the acoustic startle testing is known to decrease extracellular dopamine levels in the Acb (Humby et al., 1996). In addition, apomorphine activation of inhibitory G-protein-coupled D2Rs located in mesolimbic dopamine neurons can potently suppress their activity, resulting in decreased dopamine release in the Acb (Walters et al., 1975; de La Fuente-Fernandez et al., 2001). With fewer available ligands, more D1Rs would reside in spine necks, where the dopaminergic inputs preferentially terminate, and on the dendritic plasma membrane, where they have access to the ligands (Sesack and Pickel, 1990).

Alternatively, the D1R redistribution seen in the APO+AS group may also reflect changes occurring in other neurotransmitter systems modulated by dopamine, such as glutamate. Important clues are provided by our study in the basolateral amygdala, where we show that application of dopamine significantly decreases glutamate NMDA receptor-mediated postsynaptic currents through postsynaptic mechanisms, which may include co-trafficking of D1R and NMDA receptor (Pickel et al., 2006). This is suggested by known protein-protein interactions between the C-terminals of D1R and the NR1 subunit of NMDA receptor (Lee et al., 2002; Fiorentini et al., 2003; Pei et al., 2004; Pickel et al., 2006). Dopaminergic and glutamatergic terminals converge on the same dendritic spine in the Acb (Sesack and Pickel, 1990; Pinto et al., 2003), where NMDA receptor antagonists also disrupt sensorimotor gating (Mansbach and Geyer, 1989; Bakshi et al., 1999). Interestingly, activation of D2R reduces glutamate release only when the glutamatergic neurons are stimulated at high frequency (Yin and Lovinger, 2006). This condition may be similar to that seen in the APO+AS group, where apomorphine elicits a D2R-mediated presynaptic inhibition of glutamate release from neurons that are highly activated by AS. Furthermore, glutamatergic terminals preferentially terminate on distal dendrites and dendritic spines (Meredith 1999), where the greatest changes in D1R distribution occurred. Therefore, activation of ventral prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, or other glutamatergic afferents specifically targeting the Acb shell, not the core, could account for the observed regional specificity in D1R trafficking (Groenewegen et al., 1999; Zahm, 2000).

AS-induced changes in dendritic D1R distribution in the Acb core

In the Acb core, the AS- and/or apomorphine-induced changes in plasmalemmal distribution of D1Rs between groups were less robust compared to the shell and limited to the medium-sized dendrites. The increased plasmalemmal D1R density in the medium dendrites of the APO+AS group may be a result of the same mechanisms described above for the Acb shell. The main finding in the core, however, was that the VEH+AS group had smaller D1R-labeled dendrites compared with APO, VEH or APO+AS. One interpretation of this data is a movement of D1Rs from medium to smaller, more distal dendrites, where dopaminergic inputs are known to terminate (Groves et al., 1994). Unlike the Acb shell, the dopaminergic inputs to the Acb core principally originate from the substantia nigra pars compacta, which is associated with motor response (Brog et al., 1993; David et al., 2004). The movement of D1Rs to smaller dendrites could also reflect sensory recruitment of D1Rs to dendritic compartments where there is a selective decrease in extracellular dopamine due to the high intensity AS (Humby et al., 1996). Moreover, the dopamine release in the Acb core is influenced by glutamatergic inputs from the basolateral amygdala, one of the known regions most implicated in fear conditioning and activated by AS (Ebert and Koch, 1997; Louilot and Besson, 2000; Stevenson and Gratton, 2004).

Our data from the VEH+AS group is most consistent with trafficking of D1R to distal dendrites due to the AS-induced decrease in extracellular dopamine (Humby et al., 1996). We cannot, however, exclude the possibility that AS causes morphological changes, such as shrinkage of D1R-containing dendrites in the core. This possibility is supported by studies showing that Acb medium spiny neurons are structurally plastic. Dopamine depletion, psychostimulants and dyskinesia are all known to alter spine density and dendritic branching in Acb dendrites (Meredith et al., 1995; Robinson and Kolb, 1999; Meredith et al., 2000). In our study, however, less than one hour elapsed between AS and processing of brain tissue, and most reported changes in dendritic architecture occur after chronic manipulations. In addition, there were no significant between-group differences in spine density in the Acb, suggesting that even the highly labile dendritic spines were not affected.

Implications

These results provide the first ultrastructural evidence that the activation of dopamine D1/D2 receptors by apomorphine has little impact on D1R trafficking except when combined with biologically significant sensory inputs such as startle-evoking AS. Furthermore, they specifically identify the dendrites and spines in the Acb shell as the major neuronal compartments in which D1R distributions are most dynamically affected by sensory activation subject to dopamine modulation. There is no animal model for a complex psychiatric illness such as schizophrenia, but apomorphine-induced PPI disruption in rats provides a model of sensorimotor gating deficits seen in schizophrenia patients (Geyer et al., 2001; van den Buuse et al., 2005). The apomorphine- and AS-evoked redistribution of D1R in the Acb may significantly change striatal outputs affecting cortical activities that contribute to the sensorimotor gating deficit (Steiner and Kitai, 2000).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grant MH40342 from the National Institute of Mental Health to V.M.P., grants DA04600 and DA005130 from the National Institute of Drug Abuse to V.M.P. and M.J. Kreek, respectively, and by the Supreme Council of Freemason's Scottish Rite Fellowship to Y.H.

ABBREVIATIONS

- Acb

nucleus accumbens

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- APO

apomorphine-injected

- APO+AS

apomorphine injection followed by auditory stimulation

- AS

auditory stimulation

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- D1R

dopamine D1 receptor

- dB

decibel

- i.p.

intraperitoneal

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- p

probability value

- PB

phosphate buffer

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PFA

paraformaldehyde

- PPI

prepulse inhibition

- TBS

Tris-buffered saline

- U

unit

- VEH

vehicle-injected

- VEH+AS

vehicle injection followed by auditory stimulation

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Bakshi VP, Tricklebank M, Neijt HC, Lehmann-Masten V, Geyer MA. Disruption of prepulse inhibition and increases in locomotor activity by competitive N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;288:643–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braff DL, Grillon C, Geyer MA. Gating and habituation of the startle reflex in schizophrenic patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:206–215. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820030038005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brog JS, Salyapongse A, Deutch AY, Zahm DS. The patterns of afferent innervation of the core and shell in the “accumbens” part of the rat ventral striatum: immunohistochemical detection of retrogradely transported fluoro-gold. J Comp Neurol. 1993;338:255–278. doi: 10.1002/cne.903380209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey MP, Diewald LM, Esposito FJ, Pellicano MP, Gironi Carnevale UA, Sergeant JA, Papa M, Sadile AG. Differential distribution, affinity and plasticity of dopamine D-1 and D-2 receptors in the target sites of the mesolimbic system in an animal model of ADHD. Behav Brain Res. 1998;94:173–185. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(97)00178-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J, Aoki C, Pickel VM. Optimization of differential immunogold-silver and peroxidase labeling with maintenance of ultrastructure in brain sections before plastic embedding. J Neurosci Methods. 1990;33:113–127. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(90)90015-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David HN, Sissaoui K, Abraini JH. Modulation of the locomotor responses induced by D1-like and D2-like dopamine receptor agonists and D-amphetamine by NMDA and non-NMDA glutamate receptor agonists and antagonists in the core of the rat nucleus accumbens. Neuropharmacology. 2004;46:179–191. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M, Mansbach RS, Swerdlow NR, Campeau S, Braff DL, Geyer MA. Apomorphine disrupts the inhibition of acoustic startle induced by weak prepulses in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1990;102:1–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02245735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de La Fuente-Fernandez R, Lim AS, Sossi V, Holden JE, Calne DB, Ruth TJ, Stoessl AJ. Apomorphine-induced changes in synaptic dopamine levels: positron emission tomography evidence for presynaptic inhibition. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:1151–1159. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200110000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delle Donne KT, Chan J, Boudin H, Pelaprat D, Rostene W, Pickel VM. Electron microscopic dual labeling of high-affinity neurotensin and dopamine D2 receptors in the rat nucleus accumbens shell. Synapse. 2004;52:176–187. doi: 10.1002/syn.20018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Ciano P, Cardinal RN, Cowell RA, Little SJ, Everitt BJ. Differential involvement of NMDA, AMPA/kainate, and dopamine receptors in the nucleus accumbens core in the acquisition and performance of pavlovian approach behavior. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9471–9477. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-09471.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druhan JP, Geyer MA, Valentino RJ. Lack of sensitization to the effects of d-amphetamine and apomorphine on sensorimotor gating in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1998;135:296–304. doi: 10.1007/s002130050513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumartin B, Caille I, Gonon F, Bloch B. Internalization of D1 dopamine receptor in striatal neurons in vivo as evidence of activation by dopamine agonists. J Neurosci. 1998;18:1650–1661. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-05-01650.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert U, Koch M. Acoustic startle-evoked potentials in the rat amygdala: effect of kindling. Physiol Behav. 1997;62:557–562. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(97)00018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorentini C, Gardoni F, Spano P, Di Luca M, Missale C. Regulation of dopamine D1 receptor trafficking and desensitization by oligomerization with glutamate N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:20196–20202. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M213140200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer MA, Krebs-Thomson K, Braff DL, Swerdlow NR. Pharmacological studies of prepulse inhibition models of sensorimotor gating deficits in schizophrenia: a decade in review. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;156:117–154. doi: 10.1007/s002130100811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer MA, Swerdlow NR. Measurement of startle response, prepulse inhibition, and habituation. Curr Prot Neurosci Unit. 1998;8:1–15. doi: 10.1002/0471142301.ns0807s03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass MJ, Kruzich PJ, Colago EE, Kreek MJ, Pickel VM. Increased AMPA GluR1 receptor subunit labeling on the plasma membrane of dendrites in the basolateral amygdala of rats self-administering morphine. Synapse. 2005;58:1–12. doi: 10.1002/syn.20176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillon C, Ameli R, Charney DS, Krystal J, Braff D. Startle gating deficits occur across prepulse intensities in schizophrenic patients. Biol Psychiatry. 1992;32:939–943. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(92)90183-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groenewegen HJ, Wright CI, Beijer AV, Voorn P. Convergence and segregation of ventral striatal inputs and outputs. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;877:49–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves PM, Linder JC, Young SJ. 5-hydroxydopamine-labeled dopaminergic axons: three-dimensional reconstructions of axons, synapses and postsynaptic targets in rat neostriatum. Neuroscience. 1994;58:593–604. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90084-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara Y, Pickel VM. Overlapping intracellular and differential synaptic distributions of dopamine D1 and glutamate N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors in rat nucleus accumbens. J Comp Neurol. 2005;492:442–455. doi: 10.1002/cne.20740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara Y, Yakovleva T, Bakalkin G, Pickel VM. Dopamine D1 receptors have subcellular distributions conducive to interactions with prodynorphin in the rat nucleus accumbens shell. Synapse. 2006;60:1–19. doi: 10.1002/syn.20273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimer L, Zahm DS, Churchill L, Kalivas PW, Wohltmann C. Specificity in the projection patterns of accumbal core and shell in the rat. Neuroscience. 1991;41:89–125. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90202-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman HS, Searle JL. Acoustic Variables in the Modification of Startle Reaction in the Rat. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1965;60:53–58. doi: 10.1037/h0022325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humby T, Wilkinson LS, Robbins TW, Geyer MA. Prepulses inhibit startle-induced reductions of extracellular dopamine in the nucleus accumbens of rat. J Neurosci. 1996;16:2149–2156. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-06-02149.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ison JR, Hammond GR. Modification of the startle reflex in the rat by changes in the auditory and visual environments. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1971;75:435–452. doi: 10.1037/h0030934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley AE, Smith-Roe SL, Holahan MR. Response-reinforcement learning is dependent on N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor activation in the nucleus accumbens core. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:12174–12179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.12174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinney GG, Wilkinson LO, Saywell KL, Tricklebank MD. Rat strain differences in the ability to disrupt sensorimotor gating are limited to the dopaminergic system, specific to prepulse inhibition, and unrelated to changes in startle amplitude or nucleus accumbens dopamine receptor sensitivity. J Neurosci. 1999;19:5644–5653. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-13-05644.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamey M, Thompson M, Varghese G, Chi H, Sawzdargo M, George SR, O'Dowd BF. Distinct residues in the carboxyl tail mediate agonist-induced desensitization and internalization of the human dopamine D1 receptor. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:9415–9421. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111811200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee FJ, Xue S, Pei L, Vukusic B, Chery N, Wang Y, Wang YT, Niznik HB, Yu XM, Liu F. Dual regulation of NMDA receptor functions by direct protein-protein interactions with the dopamine D1 receptor. Cell. 2002;111:219–230. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00962-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessard A, Pickel VM. Subcellular distribution and plasticity of neurokinin-1 receptors in the rat substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area. Neuroscience. 2005;135:1309–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levey AI, Hersch SM, Rye DB, Sunahara RK, Niznik HB, Kitt CA, Price DL, Maggio R, Brann MR, Ciliax BJ. Localization of D1 and D2 dopamine receptors in brain with subtype-specific antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:8861–8865. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.8861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louilot A, Besson C. Specificity of amygdalostriatal interactions in the involvement of mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons in affective perception. Neuroscience. 2000;96:73–82. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00530-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu XY, Ghasemzadeh MB, Kalivas PW. Expression of D1 receptor, D2 receptor, substance P and enkephalin messenger RNAs in the neurons projecting from the nucleus accumbens. Neuroscience. 1998;82:767–780. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00327-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansbach RS, Geyer MA. Effects of phencyclidine and phencyclidine biologs on sensorimotor gating in the rat. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1989;2:299–308. doi: 10.1016/0893-133x(89)90035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansbach RS, Geyer MA, Braff DL. Dopaminergic stimulation disrupts sensorimotor gating in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1988;94:507–514. doi: 10.1007/BF00212846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith GE, Ypma P, Zahm DS. Effects of dopamine depletion on the morphology of medium spiny neurons in the shell and core of the rat nucleus accumbens. J Neurosci. 1995;15:3808–3820. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-03808.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith GE. The synaptic framework for chemical signaling in nucleus accumbens. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;877:140–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith GE, De Souza IE, Hyde TM, Tipper G, Wong ML, Egan MF. Persistent alterations in dendrites, spines, and dynorphinergic synapses in the nucleus accumbens shell of rats with neuroleptic-induced dyskinesias. J Neurosci. 2000;20:7798–7806. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-20-07798.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misener VL, Luca P, Azeke O, Crosbie J, Waldman I, Tannock R, Roberts W, Malone M, Schachar R, Ickowicz A, Kennedy JL, Barr CL. Linkage of the dopamine receptor D1 gene to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9:500–509. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Academic Press; Orlando: 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei L, Lee FJ, Moszczynska A, Vukusic B, Liu F. Regulation of dopamine D1 receptor function by physical interaction with the NMDA receptors. J Neurosci. 2004;24:1149–1158. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3922-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A, Palay SL, Webster HD. The Fine Structure of the Nervous System. Oxford University Press; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Pickel VM, Nirenberg MJ, Milner TA. Ultrastructural view of central catecholaminergic transmission: immunocytochemical localization of synthesizing enzymes, transporters and receptors. J Neurocytol. 1996;25:843–856. doi: 10.1007/BF02284846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickel VM, Chan J, Kash TL, Rodriguez JJ, MacKie K. Compartment-specific localization of cannabinoid 1 (CB1) and mu-opioid receptors in rat nucleus accumbens. Neuroscience. 2004;127:101–112. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickel VM, Colago EE, Mania I, Molosh AI, Rainnie DG. Dopamine D1 receptors co-distribute with N-methyl-d-aspartic acid type-1 subunits and modulate synaptically-evoked N-methyl-d-aspartic acid currents in rat basolateral amygdala. Neuroscience. 2006;142:671–690. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.06.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto A, Jankowski M, Sesack SR. Projections from the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus to the rat prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens shell: ultrastructural characteristics and spatial relationships with dopamine afferents. J Comp Neurol. 2003;459:142–155. doi: 10.1002/cne.10596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pothuizen HH, Jongen-Relo AL, Feldon J. The effects of temporary inactivation of the core and the shell subregions of the nucleus accumbens on prepulse inhibition of the acoustic startle reflex and activity in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:683–696. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds ES. The use of lead citrate at high pH as an electron-opaque stain in electron microscopy. J Cell Biol. 1963;17:208–212. doi: 10.1083/jcb.17.1.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Kolb B. Alterations in the morphology of dendrites and dendritic spines in the nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex following repeated treatment with amphetamine or cocaine. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:1598–1604. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwienbacher I, Fendt M, Hauber W, Koch M. Dopamine D1 receptors and adenosine A1 receptors in the rat nucleus accumbens regulate motor activity but not prepulse inhibition. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;444:161–169. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01622-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott L, Kruse MS, Forssberg H, Brismar H, Greengard P, Aperia A. Selective up-regulation of dopamine D1 receptors in dendritic spines by NMDA receptor activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:1661–1664. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032654599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott L, Zelenin S, Malmersjo S, Kowalewski JM, Markus EZ, Nairn AC, Greengard P, Brismar H, Aperia A. Allosteric changes of the NMDA receptor trap diffusible dopamine 1 receptors in spines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:762–767. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505557103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sesack SR, Pickel VM. In the rat medial nucleus accumbens, hippocampal and catecholaminergic terminals converge on spiny neurons and are in apposition to each other. Brain Res. 1990;527:266–279. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Roe SL, Kelley AE. Coincident activation of NMDA and dopamine D1 receptors within the nucleus accumbens core is required for appetitive instrumental learning. J Neurosci. 2000;20:7737–7742. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-20-07737.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner H, Kitai ST. Regulation of rat cortex function by D1 dopamine receptors in the striatum. J Neurosci. 2000;20:5449–5460. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-14-05449.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson CW, Gratton A. Basolateral amygdala dopamine receptor antagonism modulates initial reactivity to but not habituation of the acoustic startle response. Behav Brain Res. 2004;153:383–387. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2003.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow NR, Caine SB, Geyer MA. Regionally selective effects of intracerebral dopamine infusion on sensorimotor gating of the startle reflex in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1992;108:189–195. doi: 10.1007/BF02245306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow NR, Braff DL, Geyer MA, Koob GF. Central dopamine hyperactivity in rats mimics abnormal acoustic startle response in schizophrenics. Biol Psychiatry. 1986;21:23–33. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(86)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow NR, Mansbach RS, Geyer MA, Pulvirenti L, Koob GF, Braff DL. Amphetamine disruption of prepulse inhibition of acoustic startle is reversed by depletion of mesolimbic dopamine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1990;100:413–416. doi: 10.1007/BF02244616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow NR, Shoemaker JM, Stephany N, Wasserman L, Ro HJ, Geyer MA. Prestimulus effects on startle magnitude: sensory or motor? Behav Neurosci. 2002;116:672–681. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.116.4.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Buuse M, Garner B, Gogos A, Kusljic S. Importance of animal models in schizophrenia research. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39:550–557. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas GA, Von Zastrow M. Identification of a novel endocytic recycling signal in the D1 dopamine receptor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:37461–37469. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401034200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voorn P, Gerfen CR, Groenewegen HJ. Compartmental organization of the ventral striatum of the rat: immunohistochemical distribution of enkephalin, substance P, dopamine, and calcium-binding protein. J Comp Neurol. 1989;289:189–201. doi: 10.1002/cne.902890202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voorn P, Brady LS, Schotte A, Berendse HW, Richfield EK. Evidence for two neurochemical divisions in the human nucleus accumbens. Eur J Neurosci. 1994;6:1913–1916. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1994.tb00582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters JR, Bunney BS, Roth RH. Piribedil and apomorphine: preand postsynaptic effects on dopamine synthesis and neuronal activity. Adv Neurol. 1975;9:273–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan FJ, Swerdlow NR. Intra-accumbens infusion of quinpirole impairs sensorimotor gating of acoustic startle in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1993;113:103–109. doi: 10.1007/BF02244341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan FJ, Geyer MA, Swerdlow NR. Accumbens D2 modulation of sensorimotor gating in rats: assessing anatomical localization. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1994;49:155–163. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90470-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan FJ, Swerdlow NR. Sensorimotor gating in rats is regulated by different dopamine-glutamate interactions in the nucleus accumbens core and shell subregions. Brain Res. 1996;722:168–176. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00209-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan FJ, Taaid N, Swerdlow NR. Do D1/D2 interactions regulate prepulse inhibition in rats? Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;14:265–274. doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(95)00133-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner DM, Levey AI, Sunahara RK, Niznik HB, O'Dowd BF, Seeman P, Brann MR. D1 and D2 dopamine receptor mRNA in rat brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:1859–1863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.5.1859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss IC, Feldon J, Domeney AM. Circadian time does not modify the prepulse inhibition response or its attenuation by apomorphine. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1999;64:501–505. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00100-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin HH, Lovinger DM. Frequency-specific and D2 receptor-mediated inhibition of glutamate release by retrograde endocannabinoid signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:8251–8256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510797103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahm DS. An integrative neuroanatomical perspective on some subcortical substrates of adaptive responding with emphasis on the nucleus accumbens. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;24:85–105. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(99)00065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahm DS, Brog JS. On the significance of subterritories in the “accumbens” part of the rat ventral striatum. Neuroscience. 1992;50:751–767. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90202-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]