Abstract

Assembly of α-globin with translated, full-length and C-terminal truncated human γ-globin to form Hb F was assessed in a cell-free transcription/translation system. Polysome profiles showed two amino acid C-terminal-truncated γ-chains retained on polysomes can assemble with unlabeled holo α-chains only after puromycin-induced chain release. Two amino acid C-terminal truncated γ-chains encoded from vectors containing a stop codon at the translation termination site were released from polysomes and assembled with α-chains in the absence of puromycin addition, while removal of 11 or more amino acids from the γ-chain carboxy-terminus inhibited assembly with α-chains. These results suggest that amino acids in the HC- and H-helix γ-chain regions including amino acids 135–144 at the C-terminus in the translated γ-chains play a key role in assembly with α-chains, and that assembly occurs soon after exit of translated γ-chains from the ribosome tunnel and release from polysomes thereby preventing stable γ2 homo-dimer formation.

Keywords: Hemoglobin, Fetal hemoglobin, Hemoglobin γ-chain, Hemoglobin α-chain, Protein assembly, Polysome profile, Nascent protein, Cell-free system, AHSP (α-globin stabilizing protein), Hemoglobinopathies

The α chains of hemoglobin are in monomer/dimer equilibrium and favor the monomeric form, whereas non-α globin chains are in monomer/tetramer equilibrium and favor the tetrameric form. It is generally assumed that dissociation of these oligomeric subunits into monomers must occur before these two different chains can combine to form αβ or αγ dimers, which then associate to form tetrameric hemoglobin. In addition, assembly of the α-non-α hetero-dimer is postulated to be the main rate-limiting step in vivo to form hemoglobin, and is governed by electrostatic attractions between α and non-α partner subunits [1,2]. The γ-globin chains in Hb F are negatively charged; and, therefore, they would be expected to assemble efficiently with positively charged α chains. However, Hb F formation in vitro using purified γ- and α-globin chains is ~4 × 105 fold slower compared to Hb A formation from purified β- and α-globin chains [3]. This slow Hb F formation in vitro is to some extent due to stable γ2-dimer formation. Differences in amino acids at α1β1 and α1γ1 interaction sites and differences in surface charge also lead to different assembly rates in vitro for Hb A and Hb F [3]. In contrast, expressed radiolabeled γ- and β-globin chains made in a wheat germ, coupled cell-free transcription/translation system using γ- and β-globin cDNA expression vectors in the presence of excess unlabeled α chains added prior to translation initiation showed similar formation rates for radiolabeled Hb A and Hb F [4]. These results suggested that in the absence of free α chains the newly translated monomeric γ chains form stable homodimers in erythroid cells, which leads to lower levels of αγ dimers. In fact, in newborns with an α-thalassemia syndrome, the proportion of Hb F is lower than in individuals with all four normal α-globin genes [5]. Furthermore, it was reported that a boy with a three-gene deletional form of α thalassemia and a non-deletional form of hereditary persistence of fetal hemoglobin presented with 11% Hb Barts (γ4) and no Hb H (β4) [6], again suggesting that Hb F formation is selectively lowered under conditions of limiting amounts of stable α chains. Based on these results and the existence of a free pool of α chains in erythroid cells [7], we proposed that recently translated or nascent γ-globin chains associate with monomeric α-globin chains to form αγ hetero-dimers, prior to formation of stable γ2 homo-dimers [4].

A pool of free α chains as well as hemin appears compatible with cellular homeostasis and important for ensuring efficient assembly with non-α globin chains to form functional hemoglobin tetramers in erythroid cells [8,9]. Furthermore, globin-chain assembly with partner chains and efficient assembly of subunits to form functional hemoglobin is critical to prevent accumulation of unstable single globin chains which could lead to cell destruction. Efficient assembly also is critical for optimizing gene therapy for the treatment of hemoglobinopathies, since one therapeutic scenario involves expression of excess β-chain variants or γ-globin chains. In this report we assess determinants for Hb F assembly after expression of full-length and C-terminal truncated γ-globin chains in a wheat germ, coupled cell-free transcription/translation system. We also address whether nascently growing γ chains are able to assemble with a pool of α-globin chains to form αγ hetero-dimers followed by tetrameric Hb F.

Materials and methods

Globin-chain cDNA expression vectors

The plasmids pcDNA-α, β and γ containing the SP6 promoter and cDNAs coding for the human α, β- or γ-globin chains, respectively, were constructed from pcDNA3 and pHE2 α, β and γ by subcloning each cDNA into the HindIII/XbaI sites of pcDNA3 [3]. Transcription in vitro by SP6 RNA polymerase generates α-, β- or γ-globin mRNA which is translated in a commercially available, wheat germ cell-free transcription/ translation system. Sequence and insertion site of the α-, β- or γ-chain cDNAs in the expression vectors were confirmed by automated DNA sequence analysis using dye-tagged terminators. A variety of restriction enzymes (HindIII, MscI, EcoRI, PvuII, and NcoI) was used to generate linear expression vector templates terminated at varying lengths from 24% to 100% of wild type template. In addition, γ-globin-chain cDNA templates containing a stop codon for truncation at amino acids 144 or 135 were generated by overlap extension, PCR-induced mutagenesis.

Expression of α-, β- or γ-globin chains in a wheat germ, cell-free transcription/translation system

Expression of α-, β- or γ-globin chains in a cell-free, coupled transcription/translation system was performed using a TNT®SP6 Coupled Wheat Germ Extract System Kit (Promega, Madison, WI) containing 35S methionine (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Inc., Piscataway, NJ) [4]. A typical 50 μl reaction contained 2 μg DNA template and was incubated at 30 °C. For tetramer assembly studies, 6 ng human α- or non-α globin chains (7.5 nM) in the CO form were added to the reaction either at zero time, during or after radiolabeled partner globin-chain synthesis. Synthesized radiolabeled α-, β- or γ-globin chains, αβ or αγ dimers, and α2β2 (Hb A) or α2γ2 (Hb F) tetramers were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE)1 and cellulose acetate electrophoresis (CAE) in the presence or absence of excess unlabeled Hb A or Hb F (1.6 nM) on Titan III membranes at pH 8.6 with Super-Heme buffer (Helena Laboratories Beaumont, TX). Addition of excess Hb A or Hb F to reactions prior to electrophoresis facilitates hetero-tetramer formation of radiolabeled Hb A or Hb F, respectively, during electrophoresis [10]. Electrophoretic mobility of newly synthesized globin chains and assembled dimers and tetramers was compared with that of authentic human hemoglobins. Human α- and β-globin chains were purified from human Hb A as previously reported [11]. Removal of p-chloro mercuribenzoate from α and β chains was accomplished using 20 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and globin chains were isolated after gel filtration on a Superose 12 column (Pharmacia Biotech Inc., Piscataway, NJ). Expression and purification of globin chains were described previously [3]. Hemin was dissolved in enough 0.1 N NaOH to give about 5×10−6 M. This stock was diluted with 9 volumes of 0.5 M Tris buffer, pH 7.4, in the presence of 0.2 mM KCN. Purified recombinant human AHSP (α-hemoglobin stabilizing protein) was obtained as described previously [12].

Generation of polysome profiles by sucrose gradient fractionation

Ten to 40% (w/v) linear sucrose gradients containing 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) were prepared in Beckman ultracentrifuge tubes (14 × 89 mm) using a two-chamber gradient mixer for polysome profiling of wheat germ transcription/translation reactions. Transcription/translation reactions were incubated at 30°C for 30–60 min with 35S-labeled methionine and 1.5 mM ATP following addition of γ-globin cDNA vector in the presence or absence of excess unlabeled α chains. Reactions then were incubated for an additional 10 min in the presence or absence of puromycin (5 mM) at room temperature, and then layered onto the gradients. The SW41 rotor and ultracentrifuge were pre-cooled to 4 °C, and tubes were centrifuged at 40,000 rpm for 100 min. Gradients were separated into 11 or 5 fractions (1 or 2 ml per fraction, respectively) collected from the top of the tube, and fractions were monitored for UV absorbance at 254 nm using a ISCO UA-5 detector (Lincoln, Nebraska). Proteins in each fraction were precipitated by addition of TCA [final concentration, 5% (w/v)], and pellets were dissolved by 10 μl SDS [12% (w/v)] loading buffer prior to electrophoresis on SDS–PAGE gels followed by autoradiography.

Results

Effects of excess α-globin chains on assembly with radiolabeled non-α globin chains

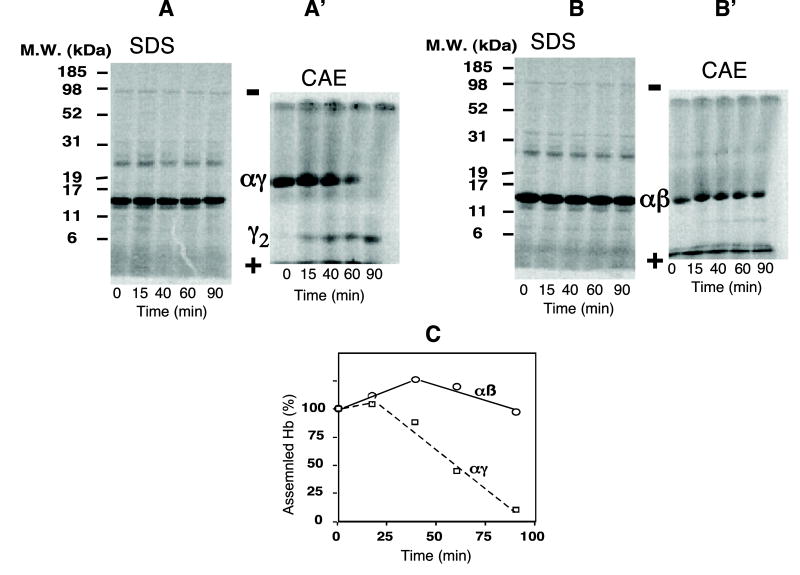

We showed previously that rates of radiolabeled hemoglobin formation were similar to that of non-α-chain synthesis in a wheat germ coupled cell-free transcription/ translation system using plasmid templates containing γ- or β-globin cDNA expression vectors when unlabeled, excess α chains were present prior to synthesis of γ chains [4]. In contrast, Hb F did not form if α chains were added to reactions after γ-globin chain synthesis had plateaued. In contrast, Hb A formed even when α chains were added after β-chain synthesis had plateaued (Fig. 1 and [4]). In this study, we evaluated the time dependency of addition of excess, unlabeled α chains for αγ assembly with newly synthesized γ chains. Cellulose acetate electrophoresis (CAE) of γ-cDNA reactions containing unlabeled α-globin chains added at different times showed radiolabeled bands co-migrating with αγ and γ2 dimers. Intensity of these bands depended on time of addition of α chains (Fig. 1A′). If reactions were incubated in the presence of α chains added at zero time or at 15 min., αγ dimers formed and only trace amounts of γ2 were seen after the 90 min. reaction (Fig. 1A′). Addition of α chains to reactions at later times failed to restore αγ hetero-dimer synthesis (Fig. 1C) and increased γ2 formation, even though the overall production of γ chains measured by SDS–PAGE intensity of γ chains was unaffected (Fig. 1A). In contrast, radiolabeled αβ formation was independent of time of α-chain addition (Fig. 1B and C). These results indicate that optimal formation in vitro of αγ hetero-dimers requires presence of excess α chains during translation of γ-globin mRNA.

Fig. 1.

Assembly of radiolabeled γ- or β-globin chains following addition of unlabeled α-globin chains at different times during reactions in a cell-free coupled transcription/translation system. Transcription/translation of γ-globin cDNA and β-globin cDNA vectors was performed following addition of unlabeled α-globin chains at different times during the 90 min reactions. Time of addition of unlabeled α chains (7.5 nM) is shown on the x-axis, and radiolabeled globin chains synthesized after 90 min are shown after SDS–PAGE ((A) and (B) are results for γ- and β-globin chains, respectively). Assembled homo-dimers and tetramers are shown following cellulose electrophoresis (CAE) (in A′ and B′ for αγ and αβ formation, respectively, or formation of their homo-dimers). Relative amounts of hetero-dimer formation for αβ and αγ as a function of time of addition of unlabeled α-globin chains during the 90 min. reaction are shown in (C).

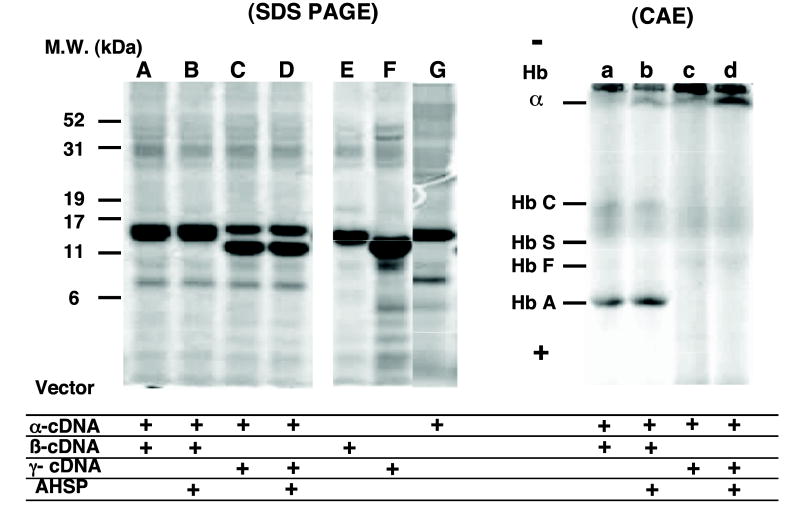

Since formation of αγ hetero-dimers was dependent on time of α-chain addition, we evaluated effects of simultaneous co-expression of γ- and α-chain reactions in the absence of added unlabeled α chains. In addition, effect of recombinant AHSP (α-globin stabilizing protein) was assessed, since it stabilizes α globin in vivo and in vitro [12]. Results of autoradiography of SDS–PAGE and CAE are shown in Fig. 2. Radiolabeled α- and β-globin chains co-migrated as a single band at ~16 kDa, whose intensity was independent of AHSP addition (Fig. 2, lanes A and B in SDS–PAGE panel). Co-expressed α- and γ-globin chains made from the cDNA expression vectors showed two bands (Fig. 2, lanes C and D in SDS–PAGE panel). We found previously that γ chains migrate faster than α- and β-globin chains on SDS–PAGE, even though molecular weights of the chains are the same (lane F versus lanes E and G of SDS–PAGE panel and [3]). Autoradiographs showing synthesis of single globin chains are shown for comparison (Fig. 2, lanes E–G in SDS–PAGE panel). Intensity of the radiolabeled α-chain band was slightly less than the non-α chains. Radiolabeled intensities of these globin bands were not affected by presence of AHSP in the reaction. Only trace amounts of Hb F were detected on CAE after co-expression of γ-plus α-globin cDNAs in the presence or absence of AHSP (Fig. 2, lanes c and d in the CAE panel), even though Hb A bands are seen after co-expression of β- and α-globin cDNAs in the presence or absence of AHSP (Fig. 2, lanes a and b in the CAE panel). In addition, radiolabeled α chains were more readily detected near the origin in the presence of AHSP in both mixtures (Fig. 2, lanes b and d in the CAE panel). These results suggest that synthesized β- and α-globin chains can form Hb A, and that translated α chains can assemble with AHSP preventing α-chain precipitation. In contrast, synthesized γ- and α-globin chains only form trace amounts of Hb F with newly synthesized α and γ chains precipitating. While AHSP can stabilize α chains, the limited amounts of newly synthesized α chains made in this cell-free system may not be sufficient to facilitate formation of αγ hetero-dimers.

Fig. 2.

Globin-chain synthesis and tetramer formation from α and non-α globin chains co-expressed in the same cell-free coupled transcription/translation reaction. Radiolabeled globin chains synthesized after a 60-min reaction containing only one expression vector (lanes E, F, and G) or equal amounts of α and non-α chain cDNA expression vectors (lanes A–D) in the presence (lanes B and D) or absence (lanes A, C, E, F and G) of AHSP (~10 nM) is shown after SDS–PAGE and autoradiography (left panel). Assembled radiolabeled hemoglobin tetramers formed from reactions corresponding to the left panel (lanes a–d) are shown after CAE and autoradiography after addition of unlabeled Hb A or Hb F (~1.6 nM) prior to electrophoresis. Positions for migration of Hbs A, F, S and C as well as free α globin are indicated.

Next, we determined the minimum amount of unlabeled free α chains required to promote assembly with newly synthesized γ chains (Fig. 3). When unlabeled α chains were added to reactions at zero time, Hb F formation was dependent on amounts of α chains added; the higher the amount, the more Hb F formed with a plateau at ~0.6 nM for unlabeled α chains. These results suggest that the limiting amounts of newly synthesized α chains made in this cell-free system (<~0.25 nM) were not sufficient, and that a relative excess of stable α chains is required to drive Hb F production and prevent γ2 homo-dimer formation.

Fig. 3.

Effects of varying unlabeled α-globin chain amounts added at zero time on formation of radiolabeled hetero-dimers. Radiolabeled αγ formation is shown after 30 min reactions as a function of unlabeled α chain amount added at 0 time. Reactions were subjected to CAE followed by autoradiography. Relative radiolabeled αγ band intensities were quantitated following autoradiography (inset) using a phosphorimaging analysis system (STORM 84D), and results expressed as relative amounts where 1.0 on the y-axis represents value obtained with 1nM unlabeled α chains added at zero time to reactions.

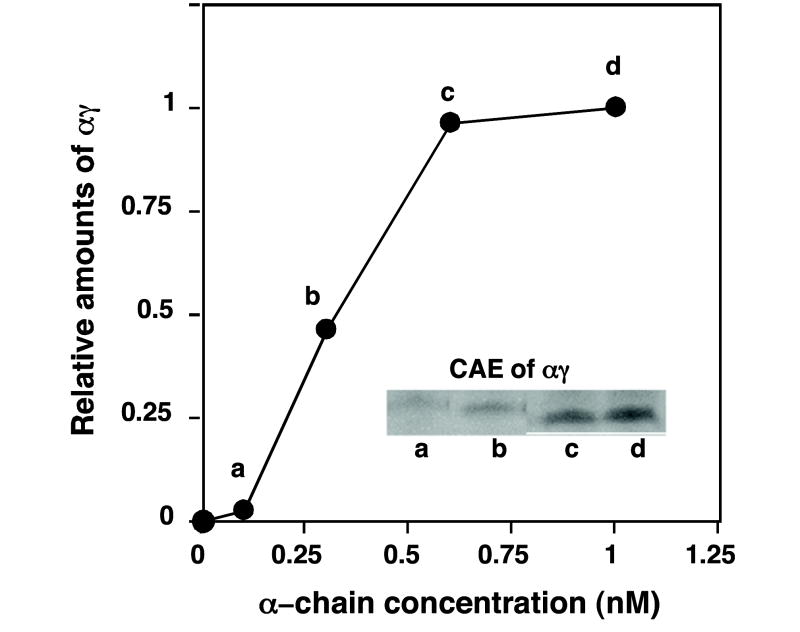

Assembly of truncated γ-globin chains with α chains

We were interested in determining whether nacently growing γ chains could assemble with preformed α chains. Since only a small fraction of radiolabeled material remains polysome-bound normally, we created using commercially available restriction enzymes a series of C-terminal γ-globin truncation mutations containing 135, 119, 86, 58 or 35 amino acids instead of the normal 146 amino acids. We designed cDNA expression constructs in which the normal chain-termination codon is absent and replaced by an amino acid coding triplet at the 3’end of the mRNA [13]. In the absence of a termination signal, most newly synthesized and growing chains remain polysomal-bound via their C-terminal amino acid. These “trapped” polypeptides can be released from polysomes by addition of puromycin [14,15]. Wild type and truncated γ-globin cDNA expression vectors ranging from 24% to 100% of wild-type length were expressed in the cell-free transcription/translation system with excess unlabeled α chains present (Fig. 4). We confirmed expression of these truncated γ chains by SDS–PAGE (Fig. 4A, left), and tested for assembly with α-globin chains (Fig. 4B and B′, middle and right). Wild type γ-globin expression vector generated radiolabeled αγ hetero-dimer in the presence or absence of puromycin addition (Fig. 4, lane 1 in B and B′), while truncated γ-globin chains containing 135 amino acids or less generated in the absence of a stop codon in the cDNA expression vector did not assemble with α-globin chains. Treatment with puromycin to release the truncated γ-globin peptides from polysomes did not lead to assembly with α-globin chains (Fig. 4B′, right).

Fig. 4.

Assembly of truncated γ chains templated from linearized cDNA expression vectors lacking a stop codon with α chains in a cell-free coupled transcription/translation system. A variety of restrictive enzymes (HindIII, MscI, EcoRI, PvuII, and NcoI) was used to generate linearized expression vector templates terminated at varying lengths from 24% to 100% (146 amino acids) of wild-type template. Transcription/translation of truncated, linearized γ-globin cDNA expression vectors was performed for 30 min following addition of unlabeled α-globin chains (7.5 nM) at zero time. Synthesis of radiolabeled globin chains (SDS–PAGE, left panel A) and assembled hetero-dimers from reactions containing (CAE, right panel B′) or lacking (CAE, middle panel B) puromycin (5 mM) are shown. Lanes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 represent results for γ-chain templates containing 146 (wild type), 135, 119, 86, 58 or 35 amino acids.

Next we prepared γ chains lacking the last two carboxyl-terminal amino acids (His and Tyr) coded from a cDNA expression vector lacking a stop codon using KpnI to generate a linearized expression vector terminated after amino acid 144. This 144 amino acid construct lacking a stop codon in the cDNA was compared to a γ-chain expression vector containing a PCR-induced stop codon after amino acid 144. The 144 amino acid chain templated in the absence of a stop codon only assembled with α chains after puromycin-induced polysome release (Fig. 5B′, lane 2p). In contrast, of the 144 and 135 amino acid constructs coded from templates containing a stop codon, only the 144 construct assembled with unlabeled α chains without puromycin treatment (Fig. 5A′, lane 2), just like full-length γ chains (Fig. 5A′, lane 1). These results indicate that assembly of nascent γ chains lacking two amino acids at the carboxy terminus first requires release from polysomes. This hetero-dimerization occurs independent of the last two amino acids in the γ-globin chains.

Fig. 5.

Assembly of two amino acid-truncated γ-globin chains from reactions containing or lacking puromycin. KpnI or MscI were used to generate linearized expression vector templates terminated after 144 and 135 amino acids in the γ chain. These templates lack a stop codon and were compared to γ-chain expression vectors containing PCR-induced stop codons after 135 or 144 amino acids. Transcription/translation reactions of these expression vector templates containing (A and A′) or lacking (B and B′) a stop codon were performed for 30 min following addition of unlabeled α-globin chains (7.5 nM) at zero time. Results were compared to those of wild type γ-globin cDNA. Synthesis of radiolabeled globin chains are shown after SDS–PAGE from templates containing (A) or lacking (B) a stop codon. Corresponding assembled hetero-dimers are shown after CAE from templates containing (A′) or lacking (B′) a stop codon. Lanes 2 and 3 represent results from two or eleven amino-acid truncated versus wild γ-cDNA expression vector (lane 1), respectively. Lane 2p and 3p in (B) and (B′) represent results for two or eleven amino acid truncated and wild γ-cDNA reactions (lane 1p), respectively, incubated with puromycin (5 mM).

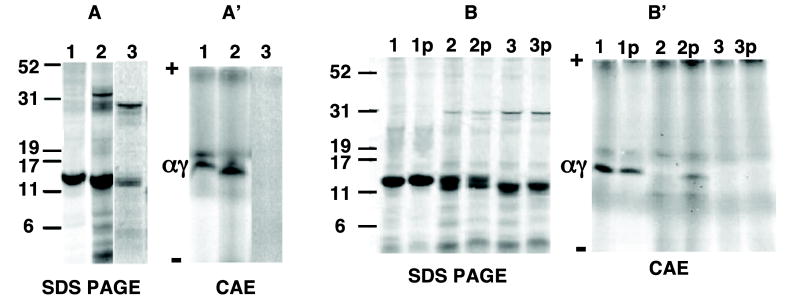

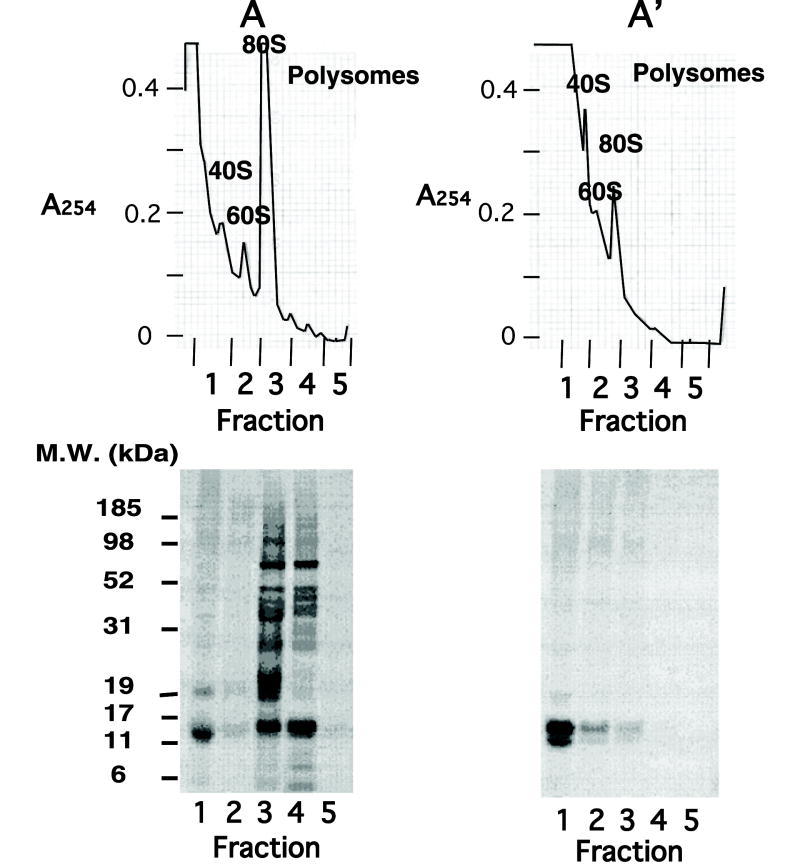

Nascent radiolabeled γ-chains lacking two amino acids coded from an expression vector lacking a stop codon were detected on polysomes (Fig. 6A, fractions 3 and 4). As expected, the radiolabeled polysome-bound chains were released after incubation with puromycin (Fig. 6A′). Without puromycin, no radiolabeled, assembled αγ hetero-dimers were detected in the polysomal fractions, even though radiolabeled ~16 kDa γ chain bands were detected in the polysomal fractions. Furthermore, in reactions containing truncated γ-globin cDNA and excess radio-iodinated α-globin chains added at zero time, no α-globin label was detected in the polysomal fractions after SDS–PAGE (data not shown). Moreover, Western blotting using monoclonal antibodies against α-globin chains showed no α chains in the polysomal fractions. It is also noteworthy that longer incubation time for reactions containing truncated γ-globin chain cDNA coded from vectors lacking a stop codon lead to release of more than half of the truncated γ chains from polysomes which could assemble with a pool of α chains just like the two amino acid-truncated γ-globin chains coded from vectors containing a stop codon after 144 amino acids. These results suggest that the region between amino acids 135 and 144 at the C-terminus of the γ chain plays a key role in assembly with α chains, and that assembly can occur only after γ-chain release from polysomes. In addition, Hb F formation may be facilitated by presence of a pool of free α chains stabilized by AHSP, which interacts with properly folded monomeric γ chains soon after translation and release from polysomes.

Fig. 6.

Polysome profiles of reactions containing KpnI-linearized two amino acid truncated γ-chain cDNA vector incubated with α chains in the presence or absence of puromycin. Transcription/translation reactions containing truncated templates were incubated at 30 °C in the presence of unlabeled α chains (7.5 nM) added at zero time. After 30 min, the reaction was incubated for an additional 10 min in the presence (A′) or absence (A) of puromycin (5 mM) at room temperature. Reactions were fractionated on sucrose gradients and fractions were collected. Absorbance at 254 nm is shown in the top panels (A and A′), while results of SDS–PAGE followed by autoradiography are shown below. Polysomal fractions are in tubes 3–5.

Discussion

Competitive mixing experiments using purified α- and non-α-globin chains and their variants have provided insights into the mechanisms of hemoglobin assembly in vivo. Previous studies demonstrated a relationship between chain electrostatic charge and assembly of globin chains [1,16-19]. Based on these results an electrostatic model of globin-chain assembly was formulated in which the rate of dimer assembly is governed by electrostatic attraction between partner chains. In addition, we found previously that surface charge and interface β-chain residues synergistically affect assembly with α chains [20]. Furthermore, carboxyl terminal residues of globin chains appear to play a critical role in hetero-dimer assembly of globin chains [21,22]. Competition experiments in vitro showed that elimination of the carboxyl-terminal two amino acids from β chains [Des (His-146, Tyr-145) β chains] promotes assembly with α chains. Thus, Des (His-146, Tyr-145) β chains assemble more readily with α chains than normal β chains due to intermolecular change in structure which may enhance monomeric β formation [21]. Our results show also that elimination of two amino acids from the carboxy terminus of γ chains allows assembly with α chains only after these truncated γ chains are released from polysomes, while removal of 11 amino acids or more does not allow assembly. These results suggest that the HC and H-helix areas near the carboxy terminus of γ chains play a critical role in folding to form stable γ chains and/or facilitates dissociation to monomers followed by assembly with α chains, and that somewhere between 135 and 144 amino acids are required for this. In addition, the crystal structure of the 50S ribosomal subunit containing the tunnel for peptidyl transferase (PT) has recently been solved at high resolution [23]. This tunnel passes through the large ribosomal subunit and emerges on the back-side of the PT center. It has been suggested that this is the normal exit from the ribosome for nascent proteins. Furthermore, the crystal structure shows that the diameter of the tunnel is too small to allow folding in its interior, and that the tunnel extends about 100 Å between the PT center and its exit, so that the ribosome protects about 40 C-terminal amino acid residues of the nascent globin chains after translation. These results suggest that dynamic assembly of γ chains with folded α chains can occur after complete translation and polysomal release of γ chains. Therefore, the C-terminal residues, after translated γ chains exit from the ribosome tunnel, then are critical for subsequent assembly with folded α chains to avoid stable γ2 homo-dimer formation, resulting in facilitation of αγ hetero-dimer and α2γ2 hetero-tetramer formation.

Mature hemoglobin in erythroid cells should be affected by differences in assembly rates of globin chains [1]. Since β- and γ-chains differ considerably in primary structure, it is likely that factors other than charge sub-domains of non-α chains affect their relative rates of assembly with α chains. Indeed, we found that γ-chain homo-dimers did not dissociate into monomers readily and formed stable homo-dimers in vitro, which inhibited their assembly with α chains in competitive mixing experiments [3]. These results indicate that several factors should influence relative production of human hemoglobin in erythroid cells, and suggested that nascent or recently translated γ-globin chains associate dynamically with monomeric stabilized α-globin chains. Our present study further confirms that intact α chains may play a critical role in formation of αγ by preventing stable γ2 formation.

In addition, we found previously that AHSP stabilizes free α chains by binding specifically to α but not β chains [12,24], and suggested that AHSP participates in hemoglobin assembly and/or hemostatis by stabilizing free α chains [24]. We believe that AHSP remains bound to α chains and promotes their stability until they encounter a desired partner, either β- or γ-globin chains in vivo [12]. Affinity of α chains for β or γ chains is greater than that for AHSP, so that in the presence of partner chains, the α-globin chain is released from AHSP to form functional tetrameric Hb A or Hb F. In fact, our results showed that α chains generated in the cell-free transcription/translation reaction were stabilized by AHSP, but did not facilitate assembly with simultaneously translated γ chains because of the low level of α-chain production in these extracts. Even though AHSP may stabilize translated α chains, the limited amounts of newly synthesized α chains in this cell-free system may not be sufficient to facilitate formation of αγ hetero-dimers. In contrast, presence of a pool of α chains is not critical for assembly with the recently translated β chains to form Hb A in this system, no doubt since β chain homo-dimers or homotetramers readily dissociate to monomers in the presence of α chains, and also have a greater affinity for α chains than AHSP, which facilitates assembly with α chains to form Hb A.

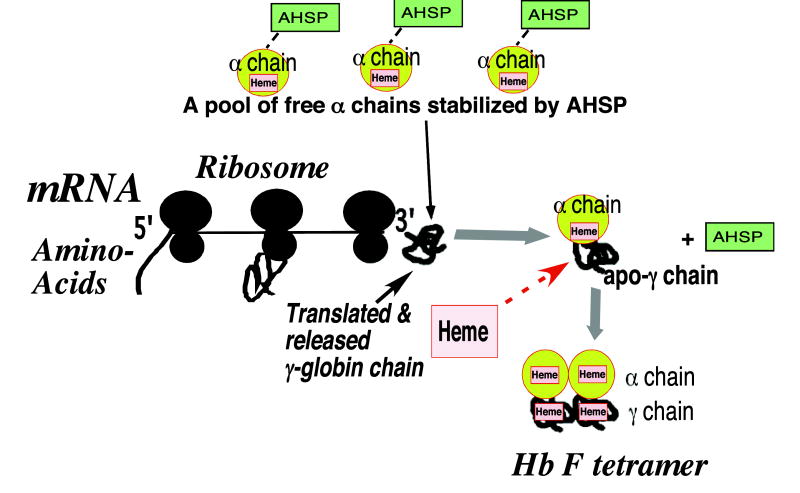

Furthermore, in vitro experiments of heme incorporation into apo-β-globin showed that apo-β-globin chains assemble with heme-incorporated α chains before heme can be correctly inserted into the heme pocket of the β-glo-bin chain [25-28]. Therefore, formation of a semi-α-hemoglobin intermediate may be critical prior to formation of functional hemoglobin. Heme insertion into the stereo-specific heme pocket of non-α chains in hetero-dimers may promote correct heme orientation for formation of functional hemoglobin. These sequential folding, assembly and heme incorporation pathways in the presence of a pool of α chains and heme in the cytoplasm may promote assembly of functional Hb F tetramers in vivo. We speculate that the free α-chain pool stabilized by binding to AHSP and the presence of heme facilitates Hb F formation (Fig. 7). Further studies in vivo are required to validate the role of a pool of α chains, AHSP and heme in hemoglobin assembly in erythroid cells.

Fig. 7.

Diagram of proposed assembly of recently translated γ-globin chains with AHSP- stabilized α chains to form Hb F in vivo. The nascently growing apo-γ globin polypeptide chains are shown during translation forming partially folded structures prior to complete translation. A pool of α chains stabilized by binding to AHSP interacts with recently translated, full-length apo-γ-globin chains dynamically after their exit from the ribosome tunnel and release generating α-apo-γ hetero-dimers and free AHSP, which results in prevention of γ2 homo-dimer formation. Assembled α-apo-γ hetero-dimers promote correct heme insertion into the heme pockets of the γ chains. In addition, α chains may act as chaperones and promote formation of stable αγ hetero-dimers by facilitating proper conformational folding of γ-globin chains during assembly.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (HL58879, HL69256, HL 70585, HL70596 and DK61692), the Cardeza Foundation for Hematologic Research, and UNICO National Inc. Foundation.

Abbreviations used

- SDS–PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacryl-amide gel electrophoresis

- CAE

cellulose acetate electrophoresis

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- PT

peptidyl transferase

References

- 1.Bunn FH. Blood. 1987;69:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaeffer JR, Kingston RE, McDonald MJ, Bunn HF. Nature. 1978;276:631–632. doi: 10.1038/276631a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adachi K, Zhao Y, Yamaguchi T, Surrey S. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:12424–12429. doi: 10.1074/jbc.c000137200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adachi K, Zhao Y, Surrey S. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:13415–13420. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200857200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stalling M, Abraham A, Abraham EC. Blood. 1983;62:75a. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chui DH, Patterson M, Dowling CE, Kazazian HH, Jr, Kendall AG. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:179–182. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199007193230307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benz EJ, Jr, Forget BG. Prog Hematol. 1975;9:107–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beuzard Y, London IM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:2863–2866. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.7.2863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shu-ChingHuang EJB., Jr . New. In: Martin H, Steinberg BGF, Douglas R, Higgs, Ronald L Nagel, editors. Disorders of Hemoglobin. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2001. pp. 146–173. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adachi K, Zhao Y, Surrey S. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2003;413:99–106. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(03)00089-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bucci E. Methods Enzymol. 1981;76:97–106. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(81)76117-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kihm AJ, Kong Y, Hong W, Russell JE, Rouda S, Adachi K, Simon MC, Blobel GA, Weiss MJ. Nature. 2002;417:758–763. doi: 10.1038/nature00803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilmore R, Collins P, Johnson J, Kellaris K, Rapiejko P. Methods Cell Biol. 1991;34:223–239. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61683-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Funfschilling U, Rospert S. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:3289–3299. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.10.3289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang S, Sakai H, Wiedmann M. J Cell Biol. 1995;130:519–528. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.3.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDonald MJ, Turci SM, Bunn HF. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1984;165:3–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bunn HF, McDonald MJ. Nature. 1983;306:498–500. doi: 10.1038/306498a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marbet NT, McDonald MJ, Turci S, Sarkar B, Szabo A, Bunn HF. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:5222–5228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawamura Y, Nakamura S. J Biochem. 1983;93:1159–1166. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a134241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamaguchi T, Yi Y, McDonald MJ, Adachi K. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;270:683–687. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joshi AA, McDonald MJ. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:8549–8553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moulton DP, Joshi AA, Morris A, McDonald MJ. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;204:956–961. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nissen P, Hansen J, Ban N, Moore PB, Steitz TA. Science. 2000;289:920. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5481.920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kong Y, Zhou S, Kihm AJ, Katein AM, Yu X, Gell DA, Mackay JP, Adachi K, Foster-Brown L, Louden CS, Gow AJ, Weiss MJ. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1457–1466. doi: 10.1172/JCI21982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vasudevan G, McDonald MJ. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:517–524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.1.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vasudevan G, McDonald MJ. J Protein Chem. 1998;17:319–327. doi: 10.1023/a:1022551131455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vasudevan G, McDonald MJ. J Protein Chem. 2000;19:583–590. doi: 10.1023/a:1007150318854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adachi K, Yang Y, Lakka V, Wehrli S, Reddy KS, Surrey S. Biochemistry. 2003;42:10252–10259. doi: 10.1021/bi030095s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]