Abstract

Background

Recent media reports have portrayed an alarming increase in apparent anabolic-androgenic steroid (AAS) use among American teenage girls; Congress even held hearings on the subject in June 2005. We questioned whether AAS use among teenage girls was as widespread as claimed.

Methods

We reviewed four large national surveys and many smaller surveys examining the prevalence of AAS use among teenage girls. Virtually all of these surveys used anonymous questionnaires. We asked particularly whether the language of survey questions might generate false-positive responses among girls who misinterpreted the term “steroid.” We also reviewed data from other countries, together with results from the only recent study (to our knowledge) in which investigators personally interviewed female AAS users.

Results

The surveys produced remarkably disparate findings, with the lifetime prevalence of AAS use estimated as high as 7.3% among ninth-grade girls in one study, but only 0.1% among teenage girls in several others. Upon examining the surveys reporting an elevated prevalence, it appeared that most used questions that failed to distinguish between anabolic steroids, corticosteroids, and over-the-counter supplements that respondents might confuse with “steroids.” Other features in the phrasing of certain questions also seemed likely to further bias results in favor of false-positive responses.

Conclusions

Many anonymous surveys, using imprecise questions, appear to have greatly overestimated the lifetime prevalence of AAS use among teenage girls; the true lifetime prevalence may well be as low as 0.1%. Future studies can test this impression by using a carefully phrased question regarding AAS use.

1. Introduction

Many men use illicit anabolic-androgenic steroids (AAS) to gain muscle for athletics or appearance (Pope and Brower, 2000). Women, by contrast, would seem unlikely to want to use AAS, since they are less likely to desire muscularity, and also risk masculinizing effects from these drugs (Gruber and Pope 2000). Surprisingly, however, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recently reported “lifetime illegal steroid use” in 7.3% of ninth-grade American girls (CDC, 2003) – sparking media warnings of a possible crisis of AAS use among girls (Anonymous, 2005; Hohler, 2005; Johnson, 2005). In June 2005, the House Government Reform Committee of the United States Congress held a public hearing regarding AAS abuse by women and girls (U.S. Congress, 2005). Subsequent media coverage has continued to suggest, despite some criticism (Collins, 2005), that AAS use among American teenage girls is widespread (Biden, 2006; Bishop, 2005; Sandalow, 2005).

Are these concerns justified? Below, we suggest that the reported prevalence of AAS use among girls is often greatly inflated by false-positive responses to survey questions, and that true AAS use among girls is rare.

2. Review of Studies

2.1 National studies

Four large national surveys have assessed the lifetime prevalence of AAS use in American teenage girls (CDC, 2003, 2005; Field et al., 2005; Johnston et al., 2005; SAMHSA, 1994) – yielding grossly discrepant estimates, ranging from 0.1% to 7.3% (Table 1). These discrepancies cannot reasonably be attributed to sampling differences, because the surveys showed no comparable differences in their prevalence estimates for other drugs, such as cannabis (Table 1). The discrepancies also cannot be explained by secular trends in the prevalence of AAS use, since all but one of the studies were performed within the last few years. Therefore, to better explain the discrepancies, we examine differences in study methodology.

Table 1. National Studies of Anabolic Steroid Use in Girls.

| Study | Method | Overall sample | Subgroup | N | Prevalence of AAS Use | Lifetime prevalence of cannabis use | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifetime | Past Year | ||||||

| CDC Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance, 2003 | Anonymous questionnaire | National sample of high school students | 9th grade girls | 1809 | 7.3% | 28.1% | |

| 10th grade girls | 1860 | 5.1% | 36.4% | ||||

| 11th grade girls | 1938 | 4.3% | 43.5% | ||||

| 12th grade girls | 1922 | 3.3% | 44.9% | ||||

| CDC Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance, 2005 | Anonymous questionnaire | National sample of high school students | 9th grade girls | 1735 | 4.8% | 27.8% | |

| 10th grade girls | 1780 | 2.5% | 35.7% | ||||

| 11th grade girls | 1821 | 2.8% | 39.4% | ||||

| 12th grade girls | 1817 | 2.3% | 42.8% | ||||

| Monitoring the Future Study, 2004 | Anonymous questionnaire | National sample of high school students | 8th grade Girls | 8708 | 1.6% | 1.0% | 15.0% |

| 10th grade Girls | 8342 | 1.4% | 0.9% | 32.8% | |||

| 12th grade Girls | 7370 | 2.3% | 1.7% | 42.6% | |||

| Growing up Today Study, 2001a | Anonymous questionnaire | Children of participants in Nurses Health Study | Girls 14-19 | 3427 | 0.1% | 0.1% | 22.6% |

| National Household Survey, 1994 | Questionnaire/Interviewb | National population sample | Girls 14-19 | 2062 | 0.1% | 0.1% | 21.4% |

Note that figures shown here are for girls studied in 2001, whereas the most recent publication of the Growing up Today Study (Field et al., 2005) presents data from 1999.

See discussion in text

2.1.1 The CDC study

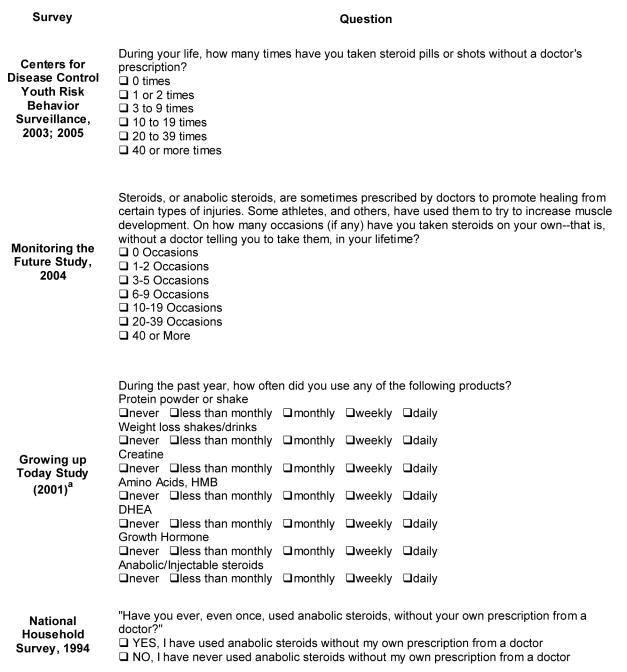

The CDC surveys (CDC, 2003, 2005) ask a single question about use of “steroid pills or shots without a doctor's prescription” (Figure 1). But this question has several deficiencies. First, it does not specify anabolic-androgenic steroids as opposed to corticosteroids; therefore a girl using, say, prednisone for poison ivy might answer positively, defeating the question's intent. Second, the phrase “without a doctor's prescription” implies that doctors typically prescribe “steroids” – whereas doctors actually almost never prescribe AAS to girls. Third, respondents may erroneously think that “steroids” are present in over-the-counter sports supplements, such as protein powders, amino acids, creatine, or supplements with names suggestive of AAS (see Table 2). Fourth, the question asks “how many times” the respondent has taken “steroids,” (i.e., “1 or 2 times,” “3 to 9 times,” etc.). But this again is misleading, because unlike other illicit drugs, AAS are not taken on individual “times,” but instead for a course measured in weeks or months (Pope and Brower, 2000). For all of these reasons, respondents may misinterpret the “steroid” question and give false-positive responses. Note that these four problems do not affect questions regarding other drugs of abuse; questions regarding, say, cocaine or marijuana are unambiguous.

Fig. 1.

Questions Regarding AAS use in Four National Surveys.

aNote that figures shown here are for girls studied in 2001, whereas the most recent publication of the Growing up Today Study presents data from 1999.

Table 2. Examples of Genuine of AAS vs. Sports Supplements.

| Genuine AAS | Sports Supplements | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| (illicit, federally controlled substances) | (licit, over-the counter, containing no AAS) | ||

| Chemical name | Brand names | Examples of Brand Names | |

| testosterone | Sustanon | creatine | Creavescent |

| Duratest | Anavol | ||

| Depo-testosterone | Betagen | ||

| Mass Stack | |||

| nandrolone decanoate | Deca-durabolin | Mass Cycle | |

| methenolone | Primobolan | adrenal steroidsa | Andro |

| Nor Andro | |||

| methandienone | Dianabol | Andro-Stack | |

| Anabol | 3 Andro Xtreme | ||

| oxandrolone | Anavar | other supplements | Lipovar |

| Anator | |||

| oxymetholone | Anadrol | Anadrox | |

| Tribex | |||

| methyltestosterone | Metandren | Anabolic Formula | |

| Mesteron | Metabolol | ||

| Methyl-Masterdrol | |||

| trenbolone | Finaject | Hi-Tech Anavar | |

| Parabolan | Hi-Tech Dianabol | ||

| Hi-Tech Metanabol | |||

| stanazolol | Winstrol | Doctor's Testosterone Gel | |

Adrenal steroids such as androstenedione and its relatives, which have only weak anabolic activity, were available over the counter until January 2005, but became federally controlled substances under the Anabolic Steroid Control Act of 2004. Only DHEA (dehydroepiandrosterone) is still legally available in supplement stores.

False-positive responses would explain the striking decrease in CDC prevalence estimates from 2003 to 2005 (see Table 1). It might initially appear that AAS use among girls has declined over these two years – but this interpretation is fallacious, because these are lifetime estimates. Consider, for example, the 7.3% estimate for ninth-graders in 2003 (95% confidence interval: ± 2.6%). If no additional ninth-graders tried AAS in the following two years, then their lifetime prevalence in 2005, when they reached 11th grade, would still be 7.3%. But the actual 2005 figure for 11th-graders is only 2.8% (95% confidence interval: ± 1.1%). This striking difference cannot reasonably be explained by sampling differences in 2003 versus 2005, since the 95% confidence intervals for these estimates do not even overlap. More likely, the proportion of false-positives declined; given the extensive recent publicity about AAS, fewer students misinterpreted the term “steroid” in 2005.

2.1.2 The Monitoring the Future Study

Unlike the CDC question, the Monitoring the Future (MTF) study question (Figure 1) mentions the specific term “anabolic steroids,” and adds that “steroids” are used for muscle development (Johnston et al., 2005). Like the CDC question, however, the MTF question still misleadingly implies that doctors typically prescribe AAS, or might “tell you to take them,” and that AAS are taken on individual “times.” Also, the question does not specifically caution respondents that AAS should not be confused with corticosteroids or sports supplements. Overall, then, this question should still yield some false positives, but fewer than the CDC – and as predicted, the MTF study indeed produces lower estimates (Table 1).

2.1.3. The Growing up Today study

Unlike the CDC and MTF studies, the Growing up Today (GUT) study (Field et al., 2005) places its “steroid” question last in a series of seven questions regarding substances typically used for muscle gains, fat loss, or athletic performance (Figure 1). Therefore, having just answered the six previous questions, respondents are well cued that “anabolic/injectable steroids” refers to AAS as opposed to, say, corticosteroids. Respondents are also unlikely to confuse “steroids” with over-the-counter supplements such as protein or creatine, since they have already answered separate questions about these categories. These features should minimize false-positive responses – and therefore the GUT study's 0.1% estimate for lifetime AAS use among teenage girls seems likely accurate.

One might argue, conversely, that the GUT study underestimates AAS use, because the phrase “anabolic/injectable steroids” might generate false-negative responses among individuals using exclusively oral AAS, and not injectable AAS. But this possibility is unlikely to cause serious error, because most AAS users do use injectable AAS, either alone or combined with oral agents (Pope and Brower, 2000). Therefore, even assuming that 50% of female AAS users used exclusively oral agents, and all of these individuals gave false-negative responses to the GUT question, the prevalence estimate would still rise only to 0.2%.

2.1.4. The National Household Survey

Unlike the previous studies, the National Household Survey (NHS) utilized trained interviewers, rather than anonymous questionnaires (SAMSHA, 1994). With an interviewer present to provide clarification and query subjects about equivocal responses, one would expect few false-positives – and indeed, for girls aged 14-19, the NHS estimated the lifetime prevalence of AAS use at only 0.1%. Even this figure might still include some false-positives, however, because approximately 95% of girls were not asked verbally about AAS, but simply answered a written questionnaire in the presence of the interviewer. Although the written question (Figure 1) appropriately uses the term “anabolic steroids,” it fails to caution that AAS should not be confused with corticosteroids or sports supplements, and it implies that AAS are drugs typically prescribed by doctors – factors conducive to false-positive responses, as discussed above. Therefore, the NHS figure, low as it is, might still overestimate of the true prevalence of AAS use in teenage girls.

It might be argued that the NHS estimate is out of date, because this survey has not assessed AAS use among teenagers since 1994. However, longitudinal data, such as the annual MTF figures (Johnston et al., 2006), show no marked rise in AAS use between 1994 and 2005 – suggesting that the 1994 NHS figures are still applicable. It might also be argued that the NHS produced false negatives because respondents were unwilling to disclose illicit AAS use to an interviewer. But this argument also seems implausible, since the NHS produced substantial prevalence estimates for other illicit drugs, such as cannabis, despite the lack of anonymity (Table 1).

In summary, upon inspecting the national studies above, it appears that among American girls 14-19, the true lifetime prevalence of AAS use is likely about 0.1%, as estimated by the GUT and NHS studies, and that the higher estimates in the CDC and MTF studies are attributable to false-positive responses.

2.1.5. Prevalence of AAS use among boys in national studies

Our discussion above would imply, parenthetically, that prevalence estimates for AAS among boys should also be greatly inflated by false-positives in the CDC study, modestly inflated in the MTF study, and relatively free of false-positives in the GUT and NHS studies. Consistent with this prediction, lifetime prevalence estimates of AAS use for boys were 6.8% in the 2003 CDC study (9th through 12th grades combined); 3.9% in the 2004 MTF study (10th and 12th grades combined); 0.4% in the 2001 GUT study; and 1.4% in the 1994 NHS study. Thus, we would suggest that the true lifetime prevalence of AAS use among American boys aged 14-19 is likely in the range of 1% or possibly even less. It should be noted, however, that many male AAS users begin use after age 19; for example, in one recent study of 48 AAS users age 18-65 (Kanayama et al., 2003) only 15 (31%) reported AAS use prior to age 20, and in the 1991 NHS, the median reported age of onset of AAS use across genders was 18 (Yesalis et al., 1993). Thus, the lifetime prevalence of AAS use is likely higher among men in their 20s or 30s.

2.2. High-school surveys

Many additional studies have estimated the prevalence of AAS use in more local samples of teenagers. Some were restricted to boys; major studies that included girls (Durant et al., 1993, 1994; Elliot et al., 2004; Faigenbaum et al., 1998; Fisher et al., 1996; Irving et al., 2002; Scott et al., 1986; Tanner et al., 1995) are summarized in Table 3. All of these studies used anonymous or confidential questionnaires; none, to our knowledge, provided an explicit definition of AAS, and none cautioned respondents that AAS should not be confused with corticosteroids or sports supplements. Several additional studies (Coker et al., 2000; Durant et al., 1995, 1999; Grunbaum et al., 1998; Middleman et al., 1995; Miller et al., 2005; Zullig et al., 2001), utilized CDC data from individual regions; these studies by definition have the same flaws as the national CDC studies already discussed, and hence are omitted from Table 3. Overall, therefore, it would follow that most estimates of AAS use among high-school girls should be greatly inflated by false-positives.

Table 3. Anonymous Surveys of American High-School Students that Report the Prevalence of Anabolic Steroid Use in Girls.

| Study | Location | Sample | N | Reported lifetime prevalence of AAS Use | Question regarding “steroids” |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Durant et al., 1993 | Georgia | ninth-grade girls | 919 | 1.9% | CDC questiona |

| Tanner et al., 1995 | Colorado | high-school girls | 3497 | 1.3% | Have you ever used anabolic steroids? |

| Scott et al., 1996 | Nebraska | middle- and high-school girls | 2522 | 0.8%b | information not supplied |

| Fisher et al., 1996 | New York City | girls in high-school gym class | 461c | 4%c | information not supplied |

| Faigenbaum et al., 1998 | Massachusetts | middle-school girls | 499 | 2.8% | Have you ever taken steroids? |

| Irving et al., 2002 | Minnesota | middle-school girls | 740d | 5.7%e | How often have you use steroids in order to gain muscle during the past year? |

| high-school girls | 1430d | 1.4%e | |||

| Elliot et al., 2004 | Oregon, Washington | female high-school athletes | 928 | 0.1% | “similar to” MTF and CDC questions |

Question was “How many times have you taken steroid pills or shots without a doctor's prescription?

Use of AAS in past 30 days

Exact number not supplied

Estimated number; exact number not supplied

Use of AAS in past 12 months

A notable exception in Table 3 is the study of Elliot and colleagues (2004), who found lifetime AAS use in only 0.1% of 928 female high-school athletes. Athletes might be expected to exhibit greater AAS use than girls in general – yet Elliott and colleagues found a far lower prevalence than the other surveys of girls as a whole. There is a likely explanation for this difference: athletes, answering a questionnaire focusing on performing-enhancing substances, would rarely misinterpret the term “steroid” – thus minimizing false-positive responses. The study's results also seem unlikely to be seriously biased by false-negative responses from genuine AAS users who denied use – since respondents readily acknowledged substantial use of other drugs, such as marijuana and diet pills. Therefore, the study's 0.1% estimate for lifetime AAS use among girls seems reasonable.

2.3. Evidence from other studies involving women

Two other recent studies offer further evidence that AAS use is rare in women and even rarer in girls. Kanayama et al. (2001) gave anonymous questionnaires to 511 clients at five gymnasiums, including two “hard-core” gymnasiums frequented by competitive bodybuilders. Since AAS use is usually associated with strength training (Pope and Brower, 2000), one would expect gymnasiums, especially “hard-core” gymnasiums, to show high concentrations of AAS users. Indeed, AAS use was reported by 18 (5.4%) of 334 men, but none of 177 women.

In the other study, Gruber and Pope (2000) systematically recruited and interviewed female AAS users; this was the only published study in the last decade, to our knowledge, reporting direct interviews of women using AAS. The investigators advertised extensively for subjects in gymnasiums – a method that had previously yielded ample numbers of male AAS users (Pope and Katz, 1988; 1994) – but found only 25 female AAS users in three metropolitan areas over a two-year period. Of these, none reported AAS use prior to age 20.

Indeed, to our knowledge, no scientific paper in the last 10 years has described a girl or woman, personally interviewed, who reported AAS use prior to age 20. Considering that approximately 23,000,000 American girls reached age 20 between 1996 and 2006, and allowing that even 0.5% of these girls used AAS before age 20, then there would be 115,000 American women, presently age 20-30, who first used AAS as teenagers. If so, it would seem remarkable that none has been described in the scientific literature.

2.4. Studies from other countries

We are aware of only one national survey of teenage AAS use outside of the United States: Galduróz and colleagues (2004) studied 48,155 Brazilian students, using a survey question designed to minimize false positives – providing specific examples of nine representative AAS widely used in Brazil (Androlone, Anabolex, etc.), and asking respondents who answered “yes” to name the AAS that they had used. Only those naming a genuine AAS were scored positive. For students age 14-19, the lifetime prevalence was 3.1% for boys, but only 0.4% for girls (Galduróz, J.C.F., personal communication, 2006).

Two other large overseas studies, though not national, are also instructive. Nilsson et al. (2001) surveyed 5827 students aged 16-17 in a county in Sweden, using an instrument that included descriptive information to clarify the term “anabolic steroids” (Nilsson, S., personal communication, 2006). Although 84 (2.9%) of the 2785 boys reported AAS use, no cases were found among the 3042 girls. By contrast, Handelsman and Gupta (1997) surveyed 13,355 high-school students in southeastern Australia and reported AAS use in 3.2% of boys and 1.2% of girls. The Australian questionnaire, however, exhibited many of the same deficits as the CDC questionnaire described above, namely asking about use of “steroids” without cautioning respondents that “steroids” should not be confused with corticosteroids or sports supplements. Thus the Australian survey, unlike the Brazilian and Swedish surveys, likely generated many false-positive responses.

3. Conclusions

We believe that quoted prevalence estimates of AAS use are often greatly inflated by false-positive responses to imprecise questions regarding “steroids” on anonymous questionnaires. Our analysis suggests that the true lifetime prevalence of AAS use among American teenage girls is well below 0.5%, and possibly only 0.1%. This impression should be tested in subsequent surveys using questions carefully designed to eliminate false-positive responses as described above. Ideally, such questions should first be tested and validated via follow-up interviews. However, since AAS use is uncommon, a fully adequate validation study might require a denominator of thousands of respondents, making it impractical. Nevertheless, false-positive responses could certainly be minimized by formulating survey questions that 1) caution respondents that AAS should not be confused with corticosteroids or over-the-counter nutritional supplements; 2) provide examples of commonly used AAS; and 3) require respondents to name the AAS that they have used, as in the Brazilian study above.

These conclusions have important implications for public health policy. If AAS use is indeed rare among teenage girls, then it may be irrational to devote extensive resources in this area; resources targeted at prevention of AAS use may be better concentrated on males, for whom the prevalence and hazards of AAS use are better documented.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIDA grant DA016744 (Drs. Kanayama, Hudson, and Pope) and NIH grant DK59570 (Dr. Field).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Omaha World-Herald. 2005. May 2, Girls use steroids, too. Drug abuse problem not limited to male athletes, young men; p. 6B. Anonymous. [Editorial] [Google Scholar]

- Biden JR., Jr Steroid side effects. The Washington Times. 2006 February 21;:A13. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop G. The Seattle Times. 2005. Oct 10, Growing issue for women; getting a boost – steroid use has increased among high-school girls; p. D5. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), United States Department of Health and Human Services. Youth risk behavior surveillance – United States. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2004. 2003;53(SS2) Data available online at: http://www.cdc.gov/HealthyYouth/yrbs/data/index.htm [Accessed on 26 October 2006] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), United States Department of Health and Human Services. Youth risk behavior surveillance – United States. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2006. 2005;55(SS5) Data available online at: http://www.cdc.gov/HealthyYouth/yrbs/data/index.htm [Accessed on 26 October 2006] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, McKeown RE, Sanderson M, Davis KE, Valois RF, Huebner S. Severe dating violence and quality of life among South Carolina high school students. Am J Prev Med. 2000;19:220–227. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00227-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins R. Barbies® for boldenone. Muscular Development. 2005 October;:286. [Google Scholar]

- Durant RH, Ashworth CS, Newman C, Rickert VI. Stability of the relationships between anabolic steroid use and multiple substance use among adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 1994;15:111–116. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(94)90537-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuRant RH, Escobedo LG, Heath GW. Anabolic-steroid use, strength training, and multiple drug use among adolescents in the United States. Pediatrics. 1995;96(1 Pt 1):23–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durant RH, Rickert VI, Ashworth CS, Newman C, Slavens G. Use of multiple drugs among adolescents who use anabolic steroids. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:922–926. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304013281304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durant RH, Smith JA, Kreiter SR, Krowchuk DP. The relationship between early age of onset of initial substance use and engaging in multiple health risk behaviors among young adolescents. Arch Pediat Adolesc Med. 1999;153:286–291. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.3.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliot DL, Goldberg L, Moe EL, DeFrancesco CA, Durham MB, Hix-Small H. Preventing substance use and disordered eating: initial outcomes of the ATHENA (Athletes Targeting Healthy Exercise And Nutrition Alternatives) program. Arch Ped Adolesc Med. 2004;158:1043–1049. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.11.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faigenbaum AD, Zaichkowsky LD, Gardner DE, Micheli LJ. Anabolic steroid use by male and female middle school students. Pediatrics. 1998;101:e6. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.5.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field AE, Austin SB, Camargo CA, Taylor CB, Striegel-Moore RH, Loud KJ, Colditz GA. Exposure to the mass media, body shape concerns, and use of supplements to improve weight and shape among male and female adolescents. Pediatrics. 2005;116:214–220. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher M, Juszczak I, Friedman SB. Sports participation in an urban high school: academic and psychologic correlates. J Adolesc Health. 1996;18:329–334. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(95)00067-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galduróz JCF, Noto AR, Fonseca AM, Carlini EA. Levantamento Nacional Sobre o Consumo de Drogas Psicotrópicas entre Estudantes do Ensino Fundamental e Médio da Rede Pública de Ensino nas 27 Capitais Brasileiras- 2004. São Paulo, Brazil: Centro Brasileiro de Informações sobre Drogas Psicotrópicas; 2004. Available online at: http://www.cebrid.epm.br/levantamento_brasil2/index.htm [Accessed on 26 October 2006] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber AJ, Pope HG., Jr Psychiatric and medical effects of anabolic-androgenic steroid use in women. Psychother Psychosom. 2000;69:19–26. doi: 10.1159/000012362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunbaum JA, Basen-Engquist K, Pandey D. Association between violent behaviors and substance use among Mexican-American and non-Hispanic white high school students. J Adolesc Health. 1998;23:153–159. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handelsman DJ, Gupta L. Prevalence and risk factors for anabolic-androgenic steroid abuse in Australian high school students. Int J Androl. 1997;20:159–164. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2605.1997.d01-285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohler B. Steroid use by young women troubling. Specialists believe problem even greater than statistics. The Boston Globe. 2005 May 10;:D1. [Google Scholar]

- Irving LM, Wall M, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M. Steroid use among adolescents: findings from Project EAT. J Adolesc Health. 2002;30:243–252. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00414-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson LA. Girls are abusing steroids too – often to get that toned look. Trenton NJ: Associated Press State and Local Wire; 2005. Apr 25, [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2004. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2005; 2005. (NIH Publication No. 05-5726) Data for 8th and 10th graders online at: http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/cgi-bin/bob/newark?study=4263&path=SAMHDA; data for 12th graders available online at: http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/cgi-bin/bob/newark?study=4264&path=SAMHDA [Accessed on 26 October 2006] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2005. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2006. (NIH Publication No. 06-5882) Available online at: http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/overview2005.pdf [Accessed on 26 October 2006] [Google Scholar]

- Kanayama G, Pope HG, Jr, Cohane G, Hudson JI. Risk factors for anabolic-androgenic steroid use among weightlifters: A case-control study. Drug Alcohol Dep. 2003;71:77–86. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00069-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanayama G, Pope HG, Jr, Gruber AJ, Borowiecki J. Over-the-counter drug use in gymnasiums: An underrecognized substance abuse problem? Psychother Psychosom. 2001;70:137–140. doi: 10.1159/000056238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleman AB, Faulkner AH, Woods ER, Emans SJ, Durant RH. High-risk behaviors among high school students in Massachusetts who use anabolic steroids. Pediatrics. 1995;96:268–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KE, Hoffman JH, Barnes GM, Sabo D, Melnick MJ, Farrell MP. Adolescent anabolic steroid use, gender, physical activity, and other problem behaviors. Subst Use Misuse. 2005;40:1637–1657. doi: 10.1080/10826080500222727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson S, Baigi A, Marklund B, Fridlund B. The prevalence of the use of androgenic anabolic steroids by adolescents in a county of Sweden. Eur J Pub Health. 2001;11:195–197. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/11.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope HG, Jr, Brower KJ. Anabolic-Androgenic Steroid Abuse. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, editors. Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry/VII. Philadelphia PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000. pp. 1085–95. [Google Scholar]

- Pope HG, Jr, Katz DL. Affective and psychotic symptoms associated with anabolic steroid use. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145:487–490. doi: 10.1176/ajp.145.4.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope HG, Jr, Katz DL. Psychiatric and medical effects of anabolic-androgenic steroid use. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:375–382. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950050035004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandalow M. Many teenage girls abuse steroids, lawmakers told; experts say it's mainly for cosmetic reasons. San Francisco Chronicle. 2005 June 16;:A1. [Google Scholar]

- Scott DM, Wagner JC, Barlow TW. Anabolic steroid use among adolescents in Nebraska schools. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 1986;53:2068–2072. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/53.17.2068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), United States Department of Health and Human Services. National Survey on Drug Use and Health (formerly called the National Household Survey) Available online at: http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/nhsda.htm; data for 1994-B survey available online at: http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/cgi-bin/SDA/SAMHDA/hsda?samhda+nhsda94b [Accessed on 26 October 2006] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner SM, Miller DW, Alongi C. Anabolic steroid use by adolescents: prevalence, motives, and knowledge of risks. Clin J Sport Med. 1995;5:108–115. doi: 10.1097/00042752-199504000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson PD, Zmuda JM, Catlin DH. Use of anabolic steroids among adolescents. New Engl J Med. 1993;329:888–889. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309163291219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Congress, House Government Reform Committee. Hearing On Steroid Use In Young Women, U.S. Representative Thomas M. Davis, Chairman, June 15, 2005. Congressional Quarterly, 2005.

- Yesalis CE, Kennedy NJ, Kopstein AN, Bahrke MS. Anabolic-androgenic steroid use in the United States. JAMA. 1993;270:1217–1221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zullig KJ, Valois RF, Huebner S, Oeltmann JE, Drane W. Relationship between perceived life satisfaction and adolescents' substance abuse. J Adolesc Health. 2001;29:271–288. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00269-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]