Abstract

We isolated a novel acid-labile yellow chromophore from the incubation of lysine, histidine and D-threose and identified its chemical structure by one and two-dimensional 1H and DEPT NMR spectroscopy combined with LC-tandem mass spectrometry. This new cross-link exhibits a UV absorbance maximum at 305 nm and a molecular mass of 451 Da. The proposed structure is 2-amino-5-(3-((4-(2-amino-2-carboxyethyl)-1H-imidazol-1-yl)methyl)-4-(1,2-dihydroxyethyl)-2-formyl-1H-pyrrol-1-yl)pentatonic acid, a cross-link between lysine and histidine with addition of two threose molecules. It was in part deduced and confirmed through synthesis of the analogous compound from n-butylamine, imidazole and D-threose. We assigned the compound the trivial name histidino-threosidine. Systemic incubation revealed that histidino-threosidine can be formed in low amounts from fructose, glyceraldehyde, methylglyoxal, glycolaldehyde, ascorbic acid, and dehydroascorbic acid, but at a much higher yield with degradation products of ascorbic acid, i.e. threose, erythrose, and erythrulose. Bovine lens protein incubated with 10 and 50 mM threose for two weeks yielded 560 and 2840 pmol/mg histidino-threosidine. Histidino-threosidine is to our knowledge the first Maillard reaction product known to involve histidine in a crosslink.

Keywords: advanced glycation end-product, yellow chromophore, fluorophore, ascorbic acid, lens, glycation, aging, erythrulose

Introduction

The Maillard reaction is initiated with the reversible formation of a Schiff base between a reducing sugar and the amino group of a protein. This relative unstable Schiff base will form a more stable Amadori product through rearrangement, which then undergoes a series of reactions to form stable advanced glycation end products (AGEs) (1). AGEs accumulate in tissue proteins during aging. Accumulation rate is accelerated in diabetes and is linked to complications such as nephropathy, retinopathy and neuropathy (2; 3).

Aging human lens crystallins similarly accumulate post-synthetic modifications and cross-links which decrease their solubility. The process is greatly accelerated during cataractogenesis, and can become extreme in brunescent cataracts. Unequivocal evidence now points to a major role of AGEs in the age-related pigmentation and crosslinking of human lens crystallins (4–6).

In specific organs like the lens, ascorbic acid may act as an important source of glycation damage. Evidence include: 1) ascorbic acid (ASA) concentration in lens is higher than most other tissues, i.e. 1 to 3 mM (7; 8); 2) ascorbic acid through its degradation products such as dehydroascorbic acid (DHA), erythrulose, erythrose, threose forms protein adducts and cross-links at much higher rate (~70 fold) compared with glucose and fructose(9). Protein modifications such as carboxymethyl-lysine, pentosidine, vesperlysine A and carboxyethyl-lysine from ascorbic acid are often identical with those forming from reducing sugars. Below we present evidence for the existence of a novel candidate cross-link from lysine, histidine, dehydroascorbic acid (DHA) or its degradation product threose or erythrulose.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Reagents of highest quality available were obtained from Sigma (St Louis, MO, U.S.A.), unless indicated otherwise. Deionized water (18.2 MΩ cm) was used for all experiment. D-Threose was purchased from Omicron Biochemicals (South Bend, Indiana, U.S.A.). Solvents for NMR experiments were purchased from Norell (Landisville, NJ, U.S.A.). LC-18 reversed phase Superclean SP tubes were purchased from Supelco (Sigma). Carbobenzoxy (Z)-protected amino acids were from Fluka/Sigma (St Louis, MO, U.S.A.).

Incubation of Z-lysine, Z-histidine with D-threose

Z-Lysine (700mg, 2.5mmol), Z-histidine (722.5 mg, 2.5 mmol) and D-threose (2.5 mmol) were dissolved in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (50 ml, pH 7.4) with 1 mM DTPA (diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid). This mixture was filtered over 0.22 μm filter unit (Millipore) and incubated at 37 °C for 3 weeks.

LC-18 SPE tubes preliminary purification

Incubation sample (25 ml) was applied to LC-18 solid phase extraction column (SUPELCO, 60 g). The solid phase extraction column was washed with 50 ml methanol (1 % TFA) and equilibrated with 50 ml water (1% TFA) before using. The incubation sample was passed through the tube and the solid phase extraction column was washed with 100 ml water containing 1% TFA. The dark brown material was then eluted with methanol containing 1% TFA.

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)

The methanol eluent was injected into preparative C-18 reversed-phase column (Vydac 218TP1022, 22 × 250 mm, 10 μm; The Separations Group, Hesperia, CA). A Waters HPLC instrument (Waters Chromatography Div., Milford, MA) with Model 510 pumps, automatic injector (model 712 WISP), and a model 680 controller were used. The column was eluted at a flow rate of 5 ml/min with 12 % acetonitrile for 10 min, and washed with a gradient of acetonitrile (12 %–42 %) for 40 min. The column eluent was monitored with an online absorbance detector (Waters 484 tunable absorbance detector) and a fluorescence detector (Waters 470 scanning fluorescence detector) at 335 and 385 nm for the excitation and the emission, respectively. The chromatograms were recorded with chromatography software (Azur, France). Fractions which had m/z values of 720 were collected by an online fraction-collector (FRAC-100, Pharmacia Biotech) and freeze-dried. This fraction was further purified with two columns. The samples were first injected into a C-18 reverse-phase semi-preparative column (Vydac 218TP1010, 10 × 250 mm, 10 μm, The Separations Group) using the same solvents and gradient as before, but with a lower flow rate: 3 ml/min. The fractions with m/z values of 720 were collected, freeze-dried, dissolved in methanol, and injected into a C-18 reverse-phase analytical column (Vydac 218 TP104, 4.6 × 250 mm, 10 μm; The Separations Group, Hesperia, CA) with the same gradient at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. After HPLC purification, the fractions were freeze-dried and stored at −80 °C.

In vitro incubation of Z-lysine, Z-histidine with sugars

Each 10 mM of glucose, ribose, fructose, erythrulose, glyceraldehyde, methylglyoxal, DHA, threose, erythrose, glycolaldehyde were incubated with 10 mM of Z-lysine and Z-histidine in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer with 1 mM DTPA (pH 7.4). After 14 days at 37 °C, the samples were injected into a C-18 analytical column (Vydac protein & peptide c18) with same gradient and solvents.

Spectroscopy

Absorption spectra were recorded with a Hewlett-Packard 8452A diode array spectrophotometer connected to an IBM PC/AT computer (Hewlett-Packard, Inc., Avondale, PA; IBM Corp., Boca Raton, FL) The sample of Z-histidino-threosidine for proton NMR spectroscopy was exchanged three times with methanol-d4 (All NMR solvents are from Norell Inc., Landisville NJ) under nitrogen atmosphere. The sample dissolved in 400 μl of 100 % methanol-d4 was transferred to a 5-mm NMR tube and scanned for 1H-NMR at 25 °C with a Varian Inova 600 NMR spectrometer. The samples of Z-histidino-threosidine for 13C-NMR, DEPT, COSY, HMQC and HMBC were exchanged three times with dimethylsulfoxide-d6, transferred to a 5-mm NMR tube and scanned overnight 25 °C with the same NMR spectrometer. The sample of histidino-threosidine for NMR spectroscopy was exchanged three times with D2O. The NMR spectrum of histidino-threosidine was taken the same as the sample for Z-histidino-threosidine. LC-MS and LC-MS/MS were performed using 2690 separation module with Quattro Ultima triple quadropole mass spectrometry detector (Waters-Micromass, Manchester, U.K.).

Determination of histidino-threosidine in bovine lens protein incubated with threose

Bovine lenses ((Pel-Freez Biologicals, Rogers, AR) were pooled, decapsulated, homogenized in water (2.5 ml/lens), and separated by centrifugation at 20,000×g. The pellet was washed twice with water (2.5 ml/lens) followed by centrifugation. The three supernatant fractions (water-soluble fractions) were pooled and extensively dialyzed against water for 2 days and freeze-dried.

50 mg/ml water-soluble bovine lens proteins were incubated with 0, 2, 10, 50 mM threose for 2 weeks in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer with 1 mM DTPA (pH 7.4). After incubation, samples were dialyzed against water for 2 days and freeze-dried. The freeze-dried pellet was sequentially digested at 37 °C for 24 h intervals by the addition of each of the following enzymes in PBS: (A) 0.12 U of peptidase (P7500, Sigma)/5 mg substrate; (B) 1.05 U of pronase E (165921, Roche)/5 mg substrate; and (D) 0.2 U of aminopeptidase M (102768, Roche). Chloroform and toluene each at a volume of 1.5μl/ml were added as antimicrobial agents. The resulting enzyme digested protein was analyzed by LC-MS/MS system. An Atlantis® dC-18 column (2.1 × 50 mm, 3 μm; Waters, Milford, MA, U.S.A.) was used. The mobile phase was 0.1 % TFA in water (Burdick&Jakson, Muskegon, MI, U.S.A.). The flow rate was 0.2 ml/min (washing of column (90 % of acetonitrile (Burdick&Jakson, Muskegon, MI, U.S.A.)) and column re-equilibration was performed between every injection). The product was detected by electrospray positive ionization-mass spectrometric multiple reaction monitoring. The ionization source temperature was 130 °C and the desolvation gas temperature 400 °C. The cone gas and desolvation gas-flow rates were 850 and 150 l/h, respectively. The capillary voltage was 3.60 kV and the cone voltage 35 V. Argon gas was in the collision cell. The collision energies for 84.00 and 279.20 fragment ions were 40 and 20 eV, respectively. Programmed molecular ion and fragment ion masses were optimized to ± 0.1 Da for multiple-reaction-monitoring detection of analyte.

Results

Isolation and purification of histidino-threosidine from in vitro incubation

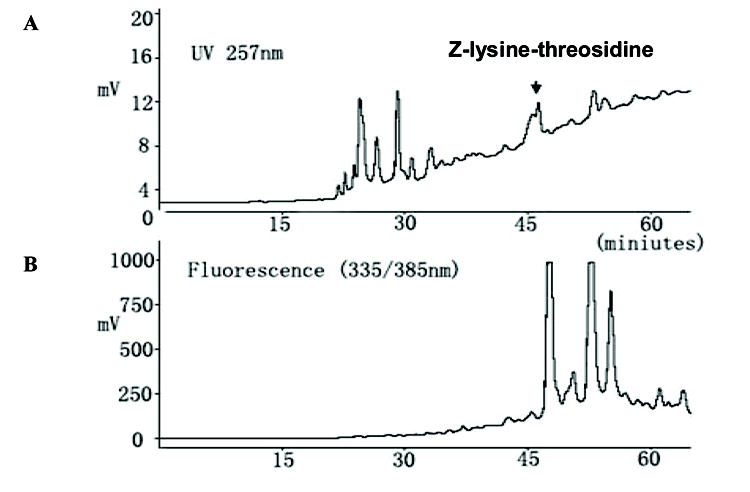

After 20 days of incubation of each 50 mM of Z-lysine, Z-histidine, and threose in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer at 37 °C, the incubation mixture was applied on LC-18 reversed phase Superclean SPE tubes and eluted with methanol. This step enriched the hydrophobic fraction of the incubation sample. The methanol eluent was fractionated by preparative reverse phase HPLC and monitored with UV detector at 257 nm (specific for Z-group) and fluorescence detector at 335/385 nm (specific for known fluorescent crosslink-pentosidine). Fractions eluting after Z-lysine were collected and monitored for compounds with m/z values exceeding 569 (i.e. the sum of the molecular weights of Z-lysine + Z-histidine) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Reversed-phase HPLC profiles showing the purification of Z-histidino-threosidine from incubation of Z-lysine, Z-histidine and D-threose by preparative column.

(A) UV absorption profile at 257 nm (B) Fluorescence profile with excitation and emission maxima at 335 nm and 385 nm.

The m/z value a peak eluting around 46 min was 720, which strongly suggested presence of a cross-linking candidate. This peak was collected, pooled, freeze-dried and further purified by analytical C-18 column. Greater than 95% purity was achieved as estimated based on NMR, HPLC and total ion scan mass spectrometry. After purification, the Z-histidino-threosidine was subjected to LC-MS and MS/MS analyses (Data not shown). MS spectra revealed a molecular ion peak with an m/z value of 720 Da, indicating a molecular mass of 719 Da. Based on the molecular mass of 719.2803 obtained by high-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were obtained on a Kratos MS-25A instrument, an empirical formula C36H41O11N5 was assigned for this molecule.

Evidence for the involvement of histidine in the crosslink

The imidazole group of histidine is known for its activity in electron donating and electron accepting functions (10; 11). Thus histidine might act as a catalyst without being a constituent in the final structure. To determine whether it is a lysine-histidine crosslink or a lysine-lysine crosslink, we incubated Z-lysine, threose, and imidazole (chosen as a histidine analog) under identical conditions. The incubation samples were analyzed by LC/MS. We found a compound with m/z of 499, which corresponds to a Z-lysine-imidazole structure. If the imidazole group would only acts as a catalyst and the compound is a lysine-lysine crosslink, the m/z should be again 720. Since no such m/z value was detected in the incubation mixtures with imidazole, the imidazole group of histidine thus did not act as a bystander catalyst in the formation of a putative lysine-lysine cross-link, but is indeed a component of the crosslink. We gave the new crosslink the name histidino-threosidine, by analogy with the work of Prabhakaram(12).

Structure elucidation of histidino-threosidine

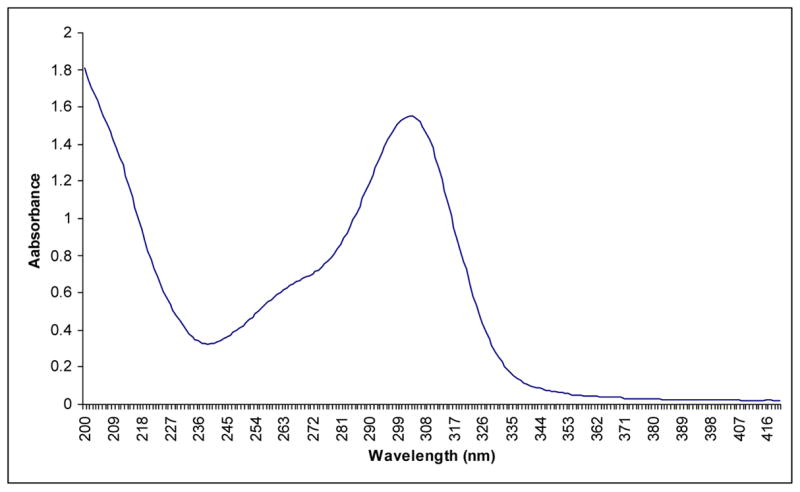

For further characterization of histidino-threosidine, we prepared it from Boc-lysine, Boc-histidine and D-threose. The Boc-compound was similarly purified with HPLC and confirmed with mass spectrometry. Greater than 95% purity was achieved as estimated based on HPLC and total ion scan mass spectrometry. The Boc-group was cleaved by reacting with ice cold TFA for 2 hours. Fig. 2 shows the absorption and spectrum of the deprotected histidino-threosidine with a maximum wavelength at 305 nm, Although we initially monitored the reaction for both UV and fluorescence and noticed co-chromatography between UV at 305 nm and 344/414 nm fluorescence activity, subsequent purification experiments resulted in a highly enriched UV active histidino-threosidine compound with trace contamination of an unknown highly fluorescent compound with unrelated excitation maximum(344 nm) that could not be completely eliminated. Based on this data and by analogy with published data from our laboratory on pyrrole carbaldehydes such as pyrraline (13) and formyl-threosyl pyrrole (14) we conclude histidino-threosidine is not fluorescent.

Fig. 2.

Absorption spectra of Boc-histidino-threosidine isolated from incubation of Boc-lysine and Boc-histidine with D-threose.

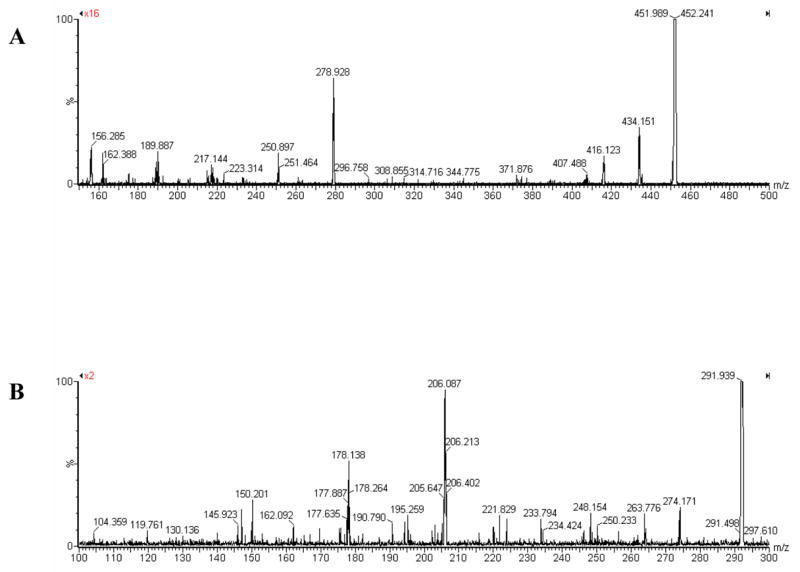

The deprotected histidino-threosidine was also analyzed by MS and MS/MS. A major peak with an m/z value of 452 Da was obtained, indicating a molecular mass of 451 Da (data not shown). The MS/MS fragmentation pattern of this compound is shown in Fig 3A. The fragments were assigned individually to the structure.

Fig. 3. Electron spray ionization-MS/MS spectra of (A) histidino-threosidine and (B) imidazole-threosidine.

For histidine-threosidine MS/MS was performed on 452. Major fragments are 434 (loss of H2O), 416 (loss of 2H2O), 407 (loss of COOH), 278.9 (loss of H2O and histidine), 250.9 (loss of COOH and histidine), 189 (loss of CHOHCH2OH, COOH and histidine), 162 (loss of CHO, CHOHCH2OH, COOH, histidine), 156 (histidine). For imidazole-threosidine MS/MS was performed on 292. Major fragments are 274 (loss of H2O), 263.8 (loss of CHO), 248 (loss of CH3CH2CH2 ), 206 (loss of OH and imidazole ring), 195 (loss of CHO and imidazole ring), 178 (loss of CHO, OH and imidazole ring), 150 (loss of –CH2-imidazole and –CHOHCH2OH).

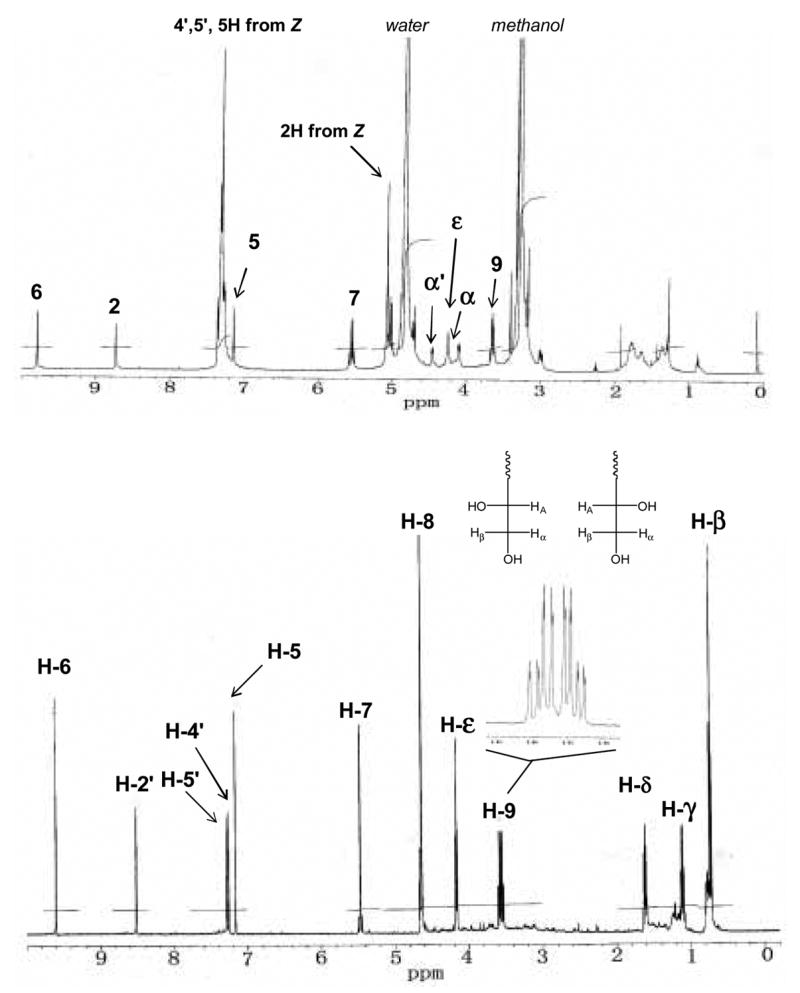

The determination of the structure of the crosslink using 1H NMR spectrum of Z-histidino-threosidine presented a problem because the large proton signals of the Z group (around 7.2 ppm) were potentially masking important aromatic protons with similar 1H NMR chemical shift. Therefore we used imidazole as histidine analog and butylamine as lysine analog to obtain NMR spectra. Incubation condition and purification process were similar to that described previously (see page 5 and 6). Greater than 95% purity was achieved as estimated based on NMR, HPLC and total ion scan mass spectrometry. The compound had the predicted m/z value of 292. As shown in Fig. 4, the proton spectrum of imidazole-threosidine conserved all the important signals in Z- histidino-threosidine.

Fig. 4. 1H-NMR spectra of Z-histidino-threosidine (A) and imidazole-threosidine (B).

Spectrum A was collected in methanol-d4, while spectrum B in D2O. Inset shows resonance of H-8 and H-9α,β.

As shown in Fig. 4, the signal at 9.8 ppm suggests an aldehyde proton. Its correlated carbon is around 179 ppm which further supports an aldehyde structure. The proton signal around 8.5, 7.25, and 7.3 ppm can be assigned to the three protons on the imidazole ring. The other 7.2 ppm proton indicates another ring in the cross-link. The shape of proton signal at 5.5 ppm suggests that they are the two mutual correlated protons on the same carbon. The HMBC spectrum shows this proton correlated with 4 or 5 aromatic carbons which suggest that it’s a –CH2 group between two aromatic rings. The protons at 4.7 and 3.5 ppm are strongly correlated according to the COSY spectrum (Fig. 5). Their correlated carbons are at 66 and 65 ppm, which indicates a –CHOH-CH2OH group in the structure. The splitting pattern of the protons at 3.5 ppm is interesting (Fig 4B). It suggests that the compound may have both R and S conformations. In R conformation, Hα is first split by Hβ and then by HA. In the same way, Hβ is first split by Hα and then by HA. Thus in R conformation, 8 splits are formed. In total, we will have 16 splits in R and S conformations. Other proton signals at 4.2, 1.6, 1.1, and 0.7 ppm can be assigned by the protons at alphabetic chain of butylamine.

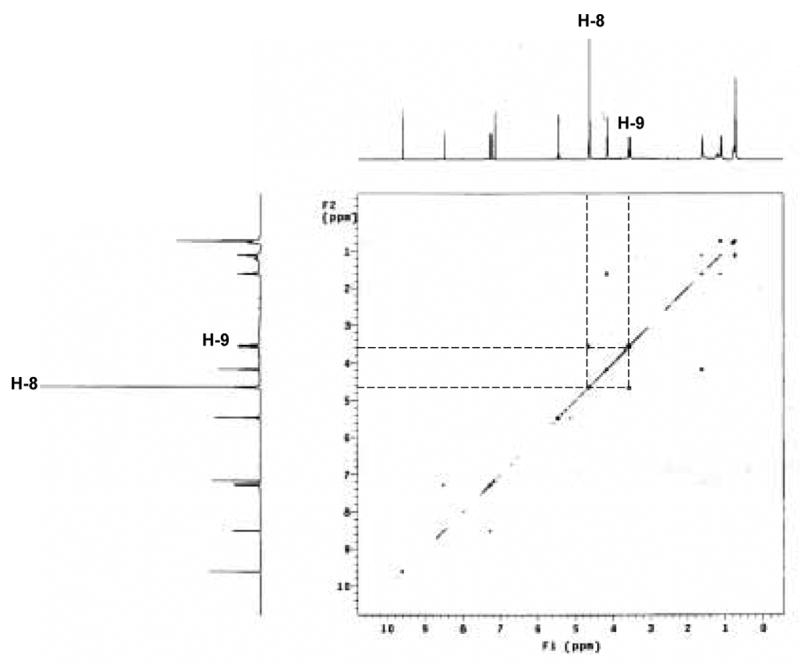

Fig. 5. 1H – 1H correlation spectroscopy (COSY) of imidazole-threosidine.

The cross signals between H-8 and H-9 are aligned in the panel.

Based on this information, a tentative structure for imidazole-threosidine and its analog emerged (Fig. 6). The newly formed ring should have –CHO, -CH2-, -CHOH-CH2OH, and -H as its side chain. Assuming the new ring involves a 4 carbon backbone from threose, the pyrrolic structure shown in Fig. 6 is proposed, except that the position of –CHO and –CH2- can be exchanged. Exchangeability also exists between –H and -CHOH-CH2OH position.

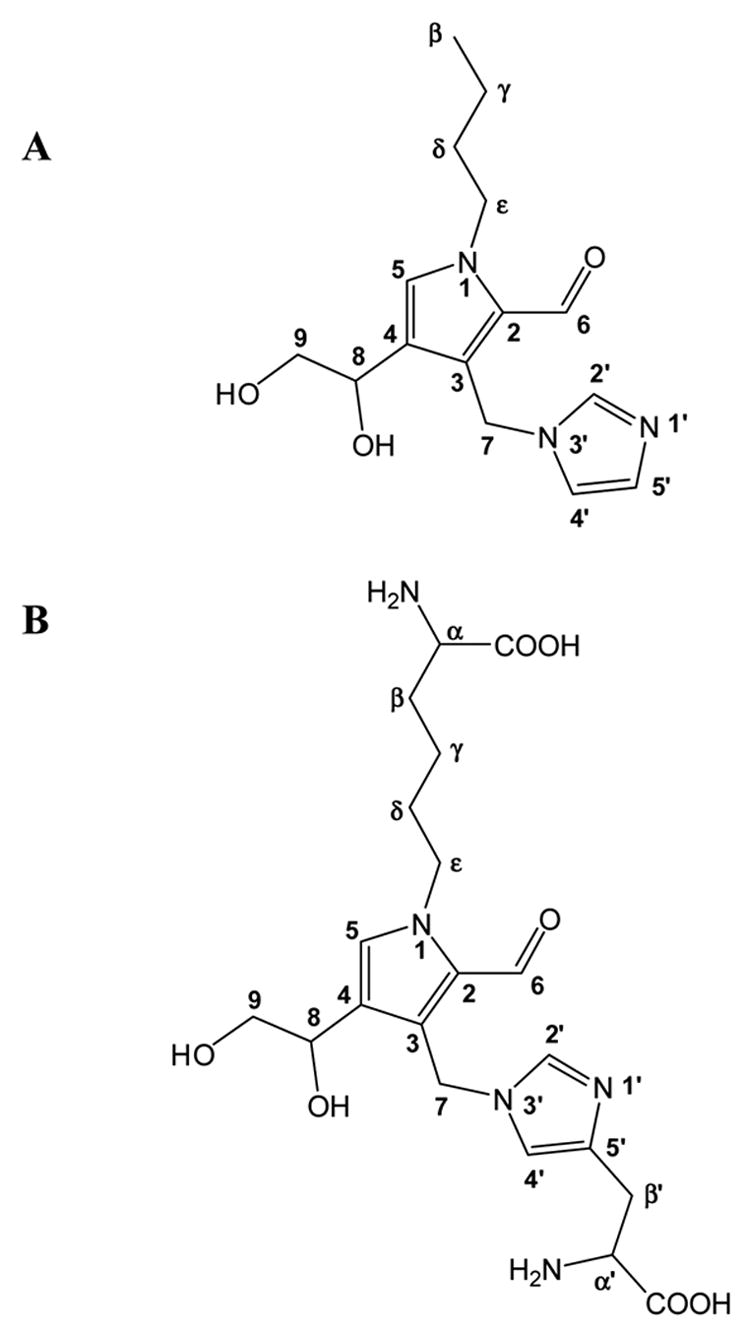

Fig. 6.

Proposed chemical structure of imidazole-threosidine (A) and histidino-threosidine (B).

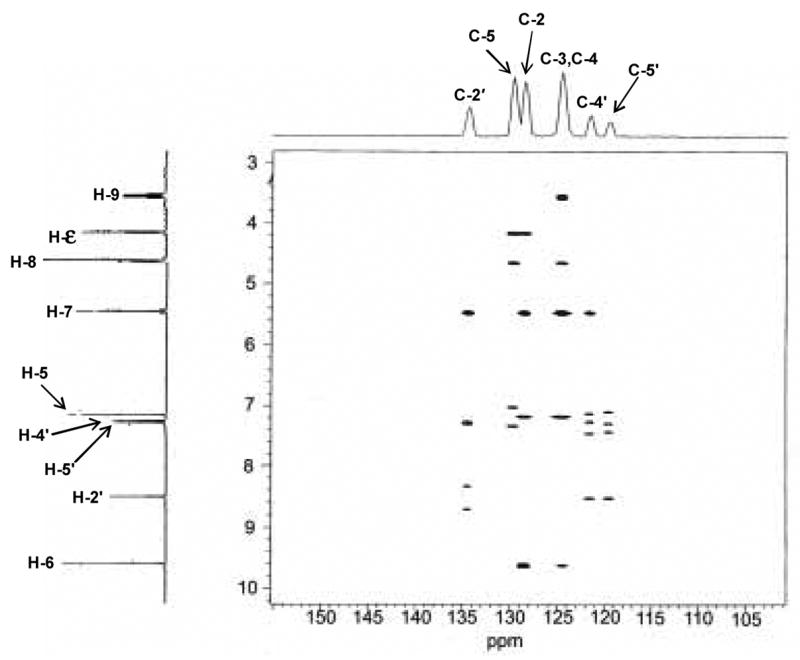

To further characterize the structure of the imidazole-threosidine analog, the exact position of –CHO, -CH2-, -CHOH-CH2OH, and –H needed to be determined. The HMBC spectrum gave us much information (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Heteronuclear multiple bond correlation (HMBC) spectroscopy of imidazole-threosidine.

With the information obtained from 1H and HMQC NMR spectra, the peak at 4.1 ppm was assigned to H-ε as shown in Fig 6. In HMBC spectrum (Fig. 7), this proton correlates with two carbons in aromatic region (129 and 130 ppm) suggesting these two carbons at the position 5 and 2 as shown in Fig. 6. In addition, the carbon at 130 ppm showed residual one-bond C-H coupling, visible as satellite doublets centered on the proton at 7.1 ppm. According to these data C-atom at 129 ppm was assigned as C-2, while signal at 130 ppm as C-5 and signal at 7.1 ppm in 1H NMR spectrum as H-5. In addition, the HMBC spectrum also showed correlation of C-5 with H-ε and H-8, which supports that C-atom at position 4 links to CHOH-CH2OH side chain. Correlation of C-2 in the HMBC spectrum with H-ε, H-7, H-5 and H-6 is compatible with proposed structure. Residual one bond correlation of C-atom at 135 ppm with proton at 8.5 ppm can be assigned as position 2′ in the imidazole ring of histidine. This C-atom also showed correlation with H-7 confirming CH2 group between two rings in the structure. Similarly, 13C NMR chemical shifts at 122 and 120 ppm can be assigned as C-4′ and C-5′. Signal at 124.5 ppm was assigned as C-4 in newly formed ring and correlation of C-4 with H-8, H-9 and H-5 is compatible with the proposed structure. Interestingly, signal at 124.5 ppm also correlated with H-6 which is from position C-4 four bonds away. Finally, it was realized that the signal at 124.5 ppm represents overlapping of C-4 and C-2 signals and according to that correlation between C-atom at 124.5 ppm and proton at 9.6 ppm can be explained as correlation between C-2 and H-6. With the all information above, the side chains at position 2 and 3 still can be exchangeable. Fig. 8 shows 13C NMR chemical shifts of proposed structures.

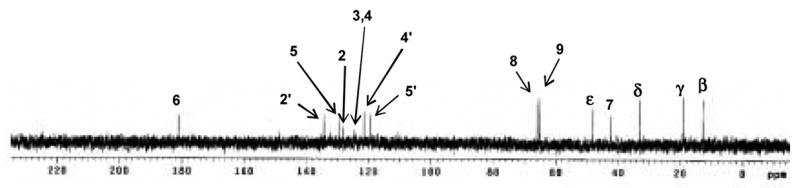

Fig. 8.

13C NMR spectrum of imidazole-threosidine.

The distortionless enhancement by polarization transfer (DEPT-135) spectra for Boc-KT2H. DEPT is a spectral editing sequence. It can discriminate CH1, CH2 and CH3 carbons. In CH2 profile, signals at 22, 32, 33, 66 ppm indicate that they are β carbon to ε carbon of lysine alphabetic chain. Signal at 31.5 ppm represents the β carbon of histidine. Signals at 67 ppm are CH2 of Z protection group. In CH profile, Signal at 56 ppm represents α carbon of lysine and histidine. There are 3 aromatic CHs in the area of 100–160 ppm which confirms 3 proton linked carbon of aromatic ring in the structure proposed. Signal at 179 ppm indicates an aldehyde carbon which confirms a –CHO side chain. Interestingly, when we refer to the structure paper of formyl threosyl pyrrole or FTP which is formed from incubation of lysine and threose(14), we found similar carbon signal at 48.5 ppm in CH2 profile and 67 ppm in CH profile, which suggests that our crosslink may also have the pyrrole linked CHOH-CH2OH group. (The DEPT spectra will be provided in supplemented data) Based on these data we propose the structure in Fig. 6B for histidino-threosidine.

To find which sugar or degradation products of sugar with the highest yield of Z-histidino-threosidine upon incubation with Z-lysine and Z-histidine, we performed systematic incubations and compared the peak area which shows m/z of 720 in HPLC profiles. Among them threose, erythrose had the highest activity, followed by erythrulose and DHA, while the yield from glucose, ribose, fructose, glyceraldehyde, MGO, glycolaldehyde were very low (Table 1). The fact that erythrulose, the main non-oxidative degradation product of ascorbic acid under physiological conditions (15), was a precursor suggests that L-erythrulose can transform into L-threose, L-erythrose and glycolaldehyde under conditions similar to physiological(16). Generally, degradation products of ascorbic acid are all good precursors of histidino-threosidine.

Table I.

Generation of compound Z- histidino-threosidine with different glycation agents. Relative yield of Z- histidino-threosidine with various sugars, oxoaldehydes, dehydroascorbate (DHA) and known degradation production of DHA. Relative yield of Z- histidino-threosidine with various sugars, oxoaldehydes, dehydroascorbate (DHA) and known degradation production of DHA.

| PRECURSOR | Yield |

|---|---|

| D-Glucose | 0 |

| D-Ribose | 0 |

| D-Fructose | Trace |

| D,L-Glyceraldehyde | Trace |

| Methylglyoxal | Trace |

| Glycolaldehyde | Trace |

| D-Threose | 34 (100)a |

| D-Erythrose | 30 (88) |

| D-Erythrulose | 3 (8.8) |

| Dehydroascorbate | 0.8 (2.4) |

Yield is given as percentage in parentheses.

The yield with threose was taken as 100 %.

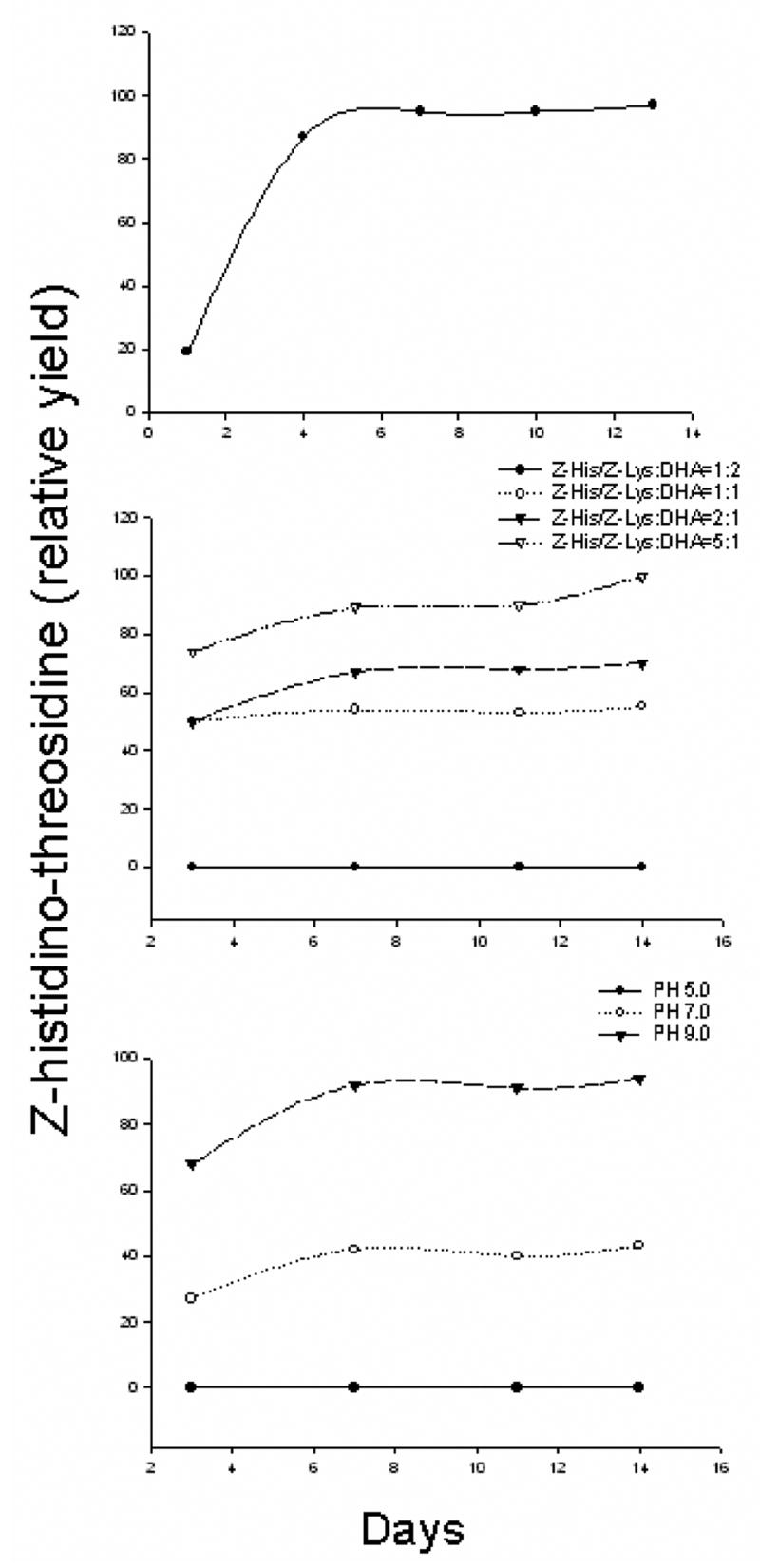

Fig. 9A shows the time dependent generation of Z-histidino-threosidine using threose as a precursor. With threose, Z- histidino-threosidine reaches a plateau in 4 days. Fig. 9B shows the effect of the ratio of Z-lysine, Z-histidine and DHA on the generation of the compound. Increase of DHA beyond the equimolar ratio totally eliminates the generation of the compound, suggesting large amounts of DHA will favor the generation of other products instead of Z- histidino-threosidine.

Fig. 9.

Effects of time (A), incubation ratios (B) and PH (C) on Z-histidino-threosidine formation from Z-threosidine, Z-histidine and threose.

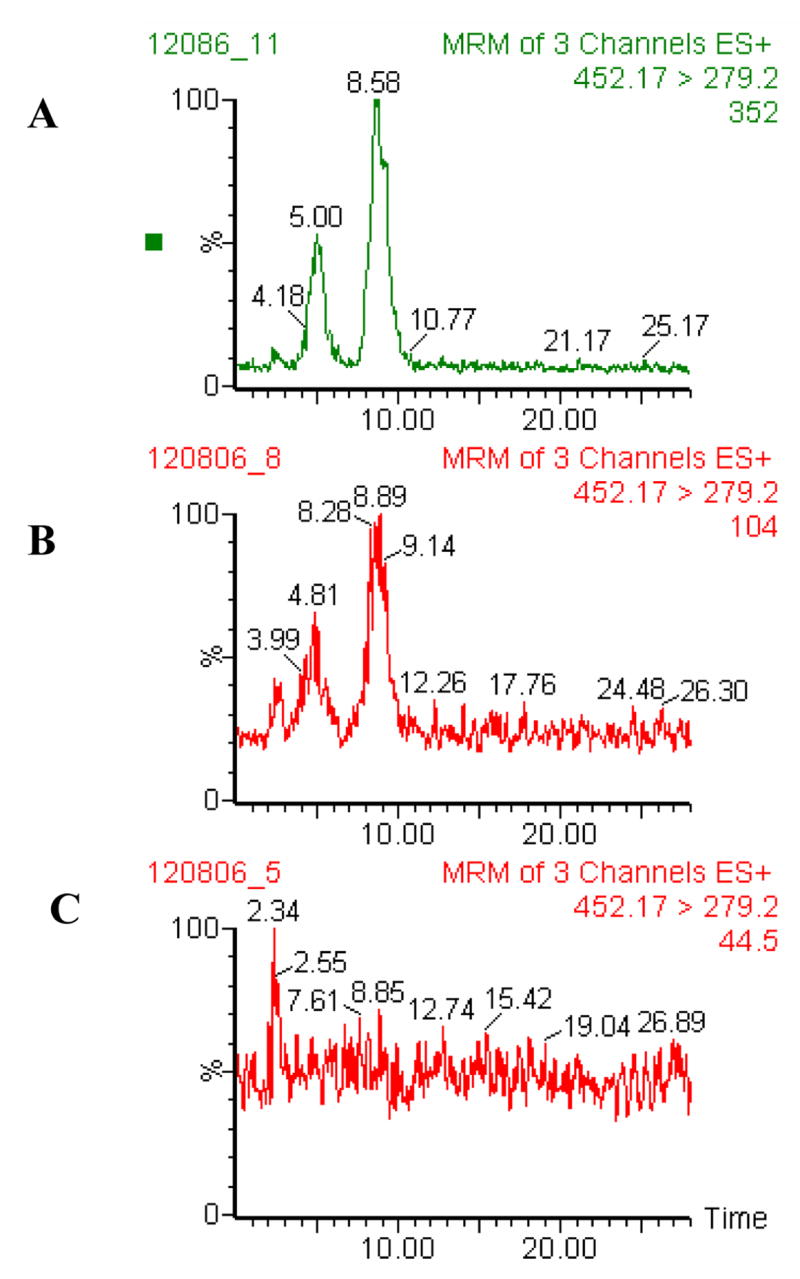

Finally, formation of Z- histidino-threosidine was favored under basic pH, as shown in Fig. 9C. When the pH value decreased to 5, its generation was totally inhibited. Histidino-threosidine was detected in bovine lens protein incubated with 10 and 50 mM threose concentrations at levels of 560 and 2840 pmol/mg of protein, respectively (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10. LC-MS/MS chromatogram of bovine lens protein (BLP) incubated with 50 (A), 10 (B) and 2 mM (C) threose.

Chromatographic conditions are described in the Experimental section

Discussion

The mechanism by which ascorbic acid and its degradation products crosslink proteins is by and large still unknown. Recently, candidate crosslinks have been described by Reihl et al. (17). These crosslinks involve arginine and lysine in an imidazole ring. While the role of these crosslinks remains to be determined, we have used a systematic approach of the search of crosslinks of lysine with histidine. Z-Protected lysine and histidine were used in order to more easily isolate the presumed crosslinks based on the anticipated hydrophobic behavior (e.g. long retention time) of the compounds. In doing so, surprisingly few candidate crosslinks emerged from which histidino-threosidine were isolated and characterized.

Histidino-threosidine has both novel and as well as features reminiscent of previously described Maillard reaction compounds. Neither glucose nor ribose was precursors. Dehydroascorbate was a precursor, albeit in relative low quantities compared to threose, erythrose and erythrulose. Somewhat surprising was the relatively low yield of histidino-threosidine from DHA in light of the data from Simpson & Ortwerth which imply erythrulose as the single major degradation product of DHA under anaerobic conditions. Assuming their observation is correct, we attribute this discrepancy to the fact that the major DHA degradation product erythrulose is not a good precursor for histidino-threosidine, and its ability to enolize to threose or erythrose is more restricted than we initially assumed. Fructose, glyceraldehyde, methylglyoxal, and glycolaldehyde generate traces of histidino-threosidine. On the other hand the pyrrole carbaldehyde structure has been observed in a number of studies. Nagaraj and Monnier reported a structure named formyl threosyl pyrrole (14). Surprisingly, except for pyralline that originates from 3-deoxyglucosone(18), there is currently limited evidence for the existence of pyrrole adducts and crosslinks in the lens. Histidino-threosidine is first Maillard crosslink found so far according to our literature search, although a histidine adducts with 4-hydroxynonenal has been previously reported (19). These authors confirmed the structure of a HNE-His imidazole Michael adduct. Similarly, a histidine adduct derived from fatty acid oxidation product malondialdehyde has been identified by Bailey’s group(20).

However, other studies have pointed to the beneficial effects and utilization of histidine as an anti-cataract agent. Carnosine is dipeptide containing histidine. Carnosine-like compounds can prevent AGE-induced crosslinking(21). Recently, Seidler et al. (22) suggested that histidine is the representative structure for an anti-crosslinking agent. And they proposed that imidazolium group of histidine may stabilize adducts formed at the primary amino group because methylation at N-1 position of imidazole abolished anti-crosslinking activity of histidine. Sayre et al. showed that carnosine also can inhibit 4-hydroxynonenal derived crosslinking by forming a 13-member cyclic adduct through initial Schiff base formation followed by conjugate addition of the imidazole group (23). Here we provide experimental evidence that histidine can form stable structure with primary amino group.

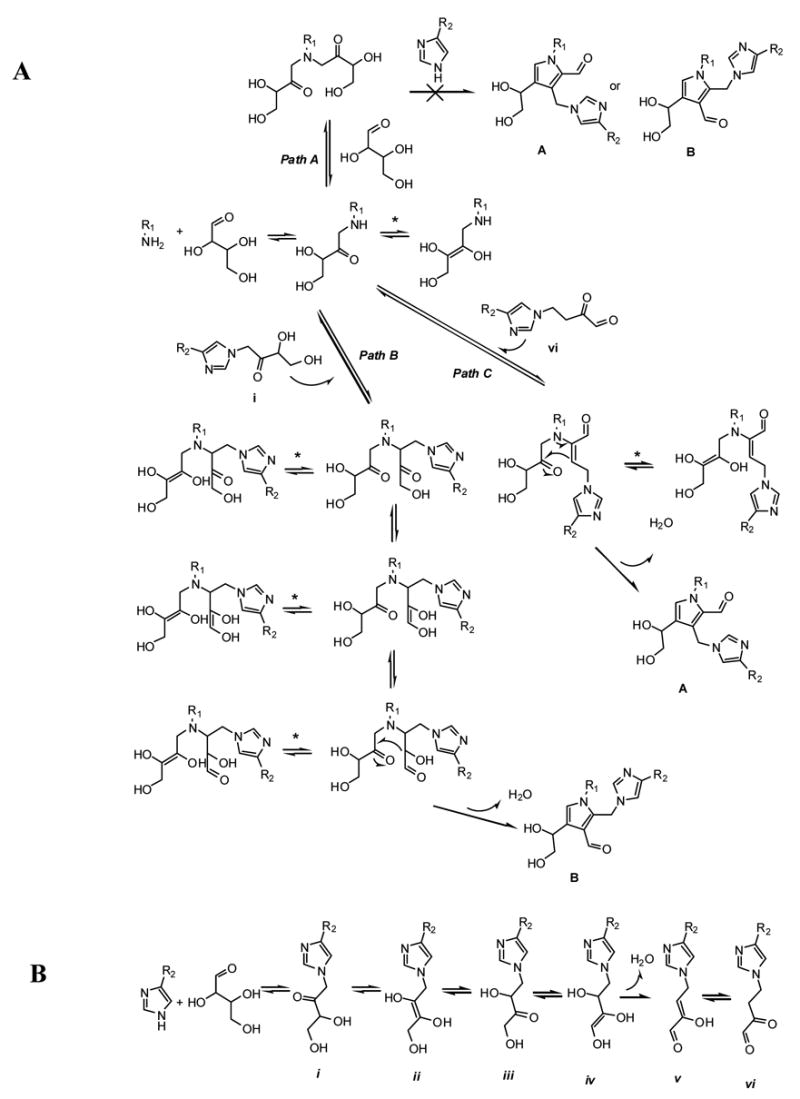

Proposed mechanism of histidino-threosidine formation is shown on Fig. 11A. The reaction starts with nucleophilic attack of lysine nitrogen to the sugar aldehyde group which, after loss of water and rearrangement gives the Amadori product. Although, formation of some cross-links with two sugar moieties, such as triosidines, involves formation of -bis-Amadori product on lysine residue (24) this path cannot generate the proposed histidino-threosidine structure A or B (Path A). However, nucleophylic attack of lysine-Amadori compound on keto-group of histidine-Amadori (Path B) can generate lysine-histidine-bis-Amadori product which after intramolecular enolization and aldol condensation can generate histidino-threosidine B. Histidino-threosidine with aldehyde group at position 2 probably follows the mechanism of crossline formation proposed by Biemel et al. (25) where dideoxysone vi (Path C), formed by enolisation of sugar part on histidine Amadori product (Fig. 11B)(26), reacts with lysine Amadori product and after ring closure generates histidino-threosidine A. Because Path C involves reaction of Amadori product and 3,4-dideoxysone which is, according to Reihl et al., not a major dideoxysone formed from Amadori product of C-4 sugars (26), this makes Path C less likely than Path B and, accordingly, structure A less likely than structure B. Loss of chirality on position 8 is the result of intramolecular tautomerisation of lysine Amadori product (equilibriums labeled with *).

Fig. 11. Proposed mechanism of formation of histidino-threosidine (A) and proposed mechanism of dideoxysone formation with histidine and threose (B).

The yield with threose was taken as 100 %.

Histidino-threosidine was detected in bovine lens proteins incubated with 10 and 50 mM but not 2 mM threose, leading to the conclusion that the formation of this crosslink requires saturation with sugars, i.e. conditions that are unlikely healthy physiological conditions. The fact that histidino-threosidine was observed only in supra-physiological concentrations of tetroses suggests that it is unlikely to be found in vivo. However the crosslink may be present in certain forms of old and cataractous human lenses in which the oxidoreductases and other detoxification enzymes are severely deficient.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Lawrence M. Sayre and Ognyan K Argirov for helpful discussions. We also thank Dr. Witold Surewicz and coworker H.E. Shuang for determination of fluorescence spectra. This work was supported by NEI grant EY07099.

Abbreviations used

- AGEs

advanced glycation end product

- COSY

correlation spectroscopy

- DEPT

distortionless enhancement by polarization transfer

- DTPA

diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid

- HMBC

heteronuclear multiple bond correlation

- HMQC

heteronuclear multiple quantum correlation

- LC-ESIMS

liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization mass spectrometry

- RP-HPLC

reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatography

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lee AT, Cerami A. Role of glycation in aging. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1992;663:63–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb38649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Genuth S, Sun W, Cleary P, Sell DR, Dahms W, Malone J, Sivitz W, Monnier VM. Glycation and carboxymethyllysine levels in skin collagen predict the risk of future 10-year progression of diabetic retinopathy and nephropathy in the diabetes control and complications trial and epidemiology of diabetes interventions and complications participants with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2005;54:3103–3111. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.11.3103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monnier VM, Sell DR, Genuth S. Glycation products as markers and predictors of the progression of diabetic complications. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1043:567–581. doi: 10.1196/annals.1333.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng R, Lin B, Lee KW, Ortwerth BJ. Similarity of the yellow chromophores isolated from human cataracts with those from ascorbic acid-modified calf lens proteins: evidence for ascorbic acid glycation during cataract formation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1537:14–26. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(01)00051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng R, Lin B, Ortwerth BJ. Separation of the yellow chromophores in individual brunescent cataracts. Exp Eye Res. 2003;77:313–325. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(03)00131-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng R, Lin B, Ortwerth BJ. Rate of formation of AGEs during ascorbate glycation and during aging in human lens tissue. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1587:65–74. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(02)00069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Varma SD, Richards RD. Ascorbic acid and the eye lens. Ophthalmic Res. 1988;20:164–173. doi: 10.1159/000266579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Varma SD. Ascorbic acid and the eye with special reference to the lens. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1987;498:280–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb23768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee KW, Mossine V, Ortwerth BJ. The relative ability of glucose and ascorbate to glycate and crosslink lens proteins in vitro off. Exp Eye Res. 1998;67:95–104. doi: 10.1006/exer.1998.0500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kipp BH, Faraj C, Li G, Njus D. Imidazole facilitates electron transfer from organic reductants. Bioelectrochemistry. 2004;64:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.bioelechem.2003.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rothery EL, Mowat CG, Miles CS, Walkinshaw MD, Reid GA, Chapman SK. Histidine 61: an important heme ligand in the soluble fumarate reductase from Shewanella frigidimarina. Biochemistry. 2003;42:13160–13169. doi: 10.1021/bi030159z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prabhakaram M, Katz ML, Ortwerth BJ. Glycation mediated crosslinking between alpha-crystallin and MP26 in intact lens membranes. Mech Ageing Dev. 1996;91:65–78. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(96)01781-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayase F, Nagaraj RH, Miyata S, Njoroge FG, Monnier VM. Aging of proteins: immunological detection of a glucose-derived pyrrole formed during maillard reaction in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:3758–3764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagaraj RH, Monnier VM. Protein modification by the degradation products of ascorbate: formation of a novel pyrrole from the Maillard reaction of L-threose with proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1253:75–84. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(95)00161-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simpson GL, Ortwerth BJ. The non-oxidative degradation of ascorbic acid at physiological conditions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1501:12–24. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(00)00009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Argirov OK, Lin B, Olesen P, Ortwerth BJ. Isolation and characterization of a new advanced glycation endproduct of dehydroascorbic acid and lysine. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1620:235–244. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(03)00002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reihl O, Lederer MO, Schwack W. Characterization and detection of lysine-arginine cross-links derived from dehydroascorbic acid. Carbohydr Res. 2004;339:483–491. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagaraj RH, Sady C. The presence of a glucose-derived Maillard reaction product in the human lens. FEBS Lett. 1996;382:234–238. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00142-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nadkarni DV, Sayre LM. Structural definition of early lysine and histidine adduction chemistry of 4-hydroxynonenal. Chem Res Toxicol. 1995;8:284–291. doi: 10.1021/tx00044a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slatter DA, Avery NC, Bailey AJ. Identification of a new cross-link and unique histidine adduct from bovine serum albumin incubated with malondialdehyde. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:61–69. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310608200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Munch G, Mayer S, Michaelis J, Hipkiss AR, Riederer P, Muller R, Neumann A, Schinzel R, Cunningham AM. Influence of advanced glycation end-products and AGE-inhibitors on nucleation-dependent polymerization of beta-amyloid peptide. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1360:17–29. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(96)00062-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hobart LJ, Seibel I, Yeargans GS, Seidler NW. Anti-crosslinking properties of carnosine: significance of histidine. Life Sci. 2004;75:1379–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Y, Xu G, Sayre LM. Carnosine inhibits (E)-4-hydroxy-2-nonenal-induced protein cross-linking: structural characterization of carnosine-HNE adducts. Chem Res Toxicol. 2003;16:1589–1597. doi: 10.1021/tx034160a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tessier FJ, Monnier VM, Sayre LM, Kornfield JA. Triosidines: novel Maillard reaction products and cross-links from the reaction of triose sugars with lysine and arginine residues. Biochem J. 2003;369:705–719. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Biemel KM, Friedl DA, Lederer MO. Identification and quantification of major maillard cross-links in human serum albumin and lens protein. Evidence for glucosepane as the dominant compound. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:24907–24915. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202681200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reihl O, Rothenbacher TM, Lederer MO, Schwack W. Carbohydrate carbonyl mobility--the key process in the formation of alpha-dicarbonyl intermediates. Carbohydr Res. 2004;339:1609–1618. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2004.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.