Abstract

Background and purpose:

Angiogenesis is a crucial step in tumour growth and metastasis. Ginsenoside-Rb1 (Rb1), the major active constituent of ginseng, potently inhibits angiogenesis in vivo and in vitro. However, the underlying mechanism remains unknown. We hypothesized that the potent anti-angiogenic protein, pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF), is involved in regulating the anti-angiogenic effects of Rb1.

Experimental approaches:

Rb1-induced PEDF was determined by real-time PCR and western blot analysis. The anti-angiogenic effects of Rb1 were demonstrated using endothelial cell tube formation assay. Competitive ligand-binding and reporter gene assays were employed to indicate the interaction between Rb1 and the oestrogen receptor (ER).

Key results:

Rb1 significantly increased the transcription, protein expression and secretion of PEDF. Targeted inhibition of PEDF completely prevented Rb1-induced inhibition of endothelial tube formation, suggesting that the anti-angiogenic effect of Rb1 was PEDF specific. Interestingly, the activation of PEDF occurred via a genomic pathway of ERβ. Competitive ligand-binding assays indicated that Rb1 is a specific agonist of ERβ, but not ERα. Rb1 effectively recruited transcriptional activators and activated an oestrogen-responsive reporter gene. Furthermore, Rb1-mediated PEDF activation and the subsequent inhibition of tube formation were blocked by the ER antagonist ICI 182,780 or transfection of ERβ siRNA, indicating ERβ dependence.

Conclusions and implications:

Here we show for the first time that the Rb1 suppressed the formation of endothelial tube-like structures through modulation of PEDF via ERβ. These findings demonstrate a novel mechanism of the action of this ginsenoside that may have value in anti-cancer and anti-angiogenesis therapy.

Keywords: ginseng, angiogenesis, endothelial cells, PEDF, oestrogen receptor

Introduction

Ginseng is a key component in Chinese traditional medicine and has been regarded as a panacea for thousands of years. Its use in North America and Europe has become increasingly popular in recent years because of its numerous purported effects in the cardiovascular, endocrine, immune, and nervous systems and apparently low rate of side effects (Rhim et al., 2002). It is one of the best-selling herbs in the United States (Helms, 2004). The major pharmacologically active components of ginseng are ginsenosides, which are steroidal saponins comprising 3–6% of ginseng. To date, more than 30 ginsenosides have been identified. One of the most abundant is the ginsenoside Rb1 and this ginsenoside constitutes 0.37–0.5% of ginseng extracts (Zhu et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2005). The root extract of the American ginseng contains on average 16.24 mg g−1 of the Rb1 ginsenoside (Zhu et al., 2004).

Various studies have indicated that Rb1 has anti-tumour and anti-angiogenic activities. Ginseng has been shown to possess cancer-preventing activities in case–control studies (Yun, 2003), and ginseng extracts inhibit the growth of human breast tumour cells in vitro (Duda et al., 1999). In terms of its anti-angiogenic activity, Rb1 and its metabolite have been shown to be very effective in suppressing tumour angiogenesis in vivo (Sato et al., 1994; Shibata, 2001). Using primary endothelial cell cultures, Rb1 was shown to inhibit functional neovascularization into a polymer scaffold in vivo and the proliferation, chemoinvasion, and tubulogenesis of endothelial cells in vitro (Sengupta et al., 2004). Although these findings highlight the therapeutic potential of Rb1 as a novel modality to treat cancer and other angiogenesis-dependent diseases, the receptors for Rb1 and the signalling molecules that mediate the anti-angiogenic activity of Rb1 are still unknown.

Angiogenesis, the growth of new capillaries from the pre-existing microvessels, is a tightly regulated event integral to many physiological or pathological conditions, including development, wound healing, and tumour growth (Risau, 1997). Among many angiogenesis regulators, pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) has been described as the most potent natural inhibitor of angiogenesis known to date (Dawson et al., 1999). It is a 50 kDa secreted glycoprotein expressed ubiquitously in many tissues and cells of the body, including endothelial cells (Tombran-Tink, 2005). Loss of PEDF expression is associated with angiogenic activity in cancer cells, whereas PEDF, as a soluble protein or when delivered using viral-mediated gene transfer strategies, is highly effective against endothelial cell growth, migration, and neovascularization (Duh et al., 2002; Abe et al., 2004). PEDF can also antagonize the effects of a number of important angiogenic inducers, including vascular endothelial growth factor (Dawson et al., 1999). Some of the mechanisms regulating PEDF expression have been investigated. The presence of a putative oestrogen responsive element in the PEDF promoter, and the modulation by 17β-oestradiol (E2) of PEDF expression are highly suggestive of an oestrogen receptor (ER) involvement in PEDF's biological functions (Tombran-Tink et al., 1996; Cheung et al., 2006; Li et al., 2006). The fact that Rb1 is a steroidal saponin, which in structure resembles oestrogen, and biochemical studies also indicate that Rb1 has oestrogen-like properties and exerts its action via the activation of ER (Lee et al., 2003; Cho et al., 2004) further suggest that PEDF, ER, and Rb1 may be linked in a common pathway that controls angiogenesis.

There are two subtypes of the ER, ERα and ERβ. Although ERα and ERβ share a high sequence homology (96%) in their DNA-binding domain, the divergence of their ligand-binding domains (LBDs) (58% homology) leads to dissimilar ligand preferences and affinities of these two ER subtypes. After binding of the ligand to these receptors, the complex interacts with specific DNA sequences, known as oestrogen responsive elements (ERE), on the promoter regions of target genes, recruit coregulators, and initiate transcription (Gustafsson, 2000a).

In this study, we aimed to elucidate the mechanism of the anti-angiogenic action of Rb-1. The results presented here clearly show that Rb1 regulates the expression and action of the anti-angiogenic factor PEDF and that this regulation is under the control of ERβ, but not ERα.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were obtained from Clonetics (San Diego, CA, USA) and cultured in medium 199 supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 20 μg ml−1 endothelial cell growth supplement (ECGS), 90 U ml−1 heparin, and 1% penicillin–streptomycin–neomycin in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 95% air/5% CO2. HUVEC between passages 2–8 were used in these studies to ensure the genetic stability of the culture. Cells were then adapted in phenol red-free medium supplemented with 20% charcoal/dextran-treated FBS (for removal of endogenous steroids in the serum) 48 h before each assay.

Treatments

The regulation of PEDF by Rb1 was determined by treating HUVEC with increasing concentrations of Rb1 between 0 and 500 nM for 24 h. Conditioned media and total HUVEC cell lysates were analysed for PEDF expression by western blot. RNA was harvested for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis.

For inhibition assays, cells were pretreated with 10 μM of the ER antagonist ICI 182,780 for 30 min before the addition of Rb1 or DMSO alone, which served as a control. Cell transfection was performed using siLentfect reagent (Bio-Rad, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, HUVEC were seeded in six-well plates and grown to 70–80% confluence. In total, 10 nM ERβ small interfering RNA (siRNA) was added per well. After 24 h, the cells were incubated with or without Rb1 for an additional 24 h before protein levels determination or tube formation assay. As a non-specific siRNA control, scrambled siRNA was used.

Tube formation assay

HUVEC (1 × 105 cells per well) were seeded in growth factor-reduced Matrigel-coated 24-well plates in phenol red-free medium 199 containing 1% charcoal/dextran-treated FBS. Cells were incubated in the absence or presence of 250 nM Rb1, conditioned medium derived from Rb1-stimulated HUVEC (Rb1-CM), a combination of Rb1 or Rb1-CM with either ER siRNA or PEDF-neutralizing antibody, or with ICI 182,780 for 16 h at 37°C. Images were captured under phase contrast microscopy (× 10) using a CCD camera. Twelve microscopic fields were randomly selected for each well. The anti-angiogenic activities were determined by counting the branch points of the formed tubes and the average numbers of branch points were calculated as described previously (Yue et al., 2006). Each experiment was repeated three times.

Western blot analysis

Equal amounts of proteins for each sample were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was then incubated with the indicated primary antibodies for 3 h, followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies and binding visualized by an ECL detection system. Where indicated, the membranes were stripped and re-probed with another antibody. The density of the bands was quantified by densitometric analysis using Metamorph software.

Real-time PCR

Total RNAs were extracted with TRIzol reagent and reverse transcribed using Superscript II First-strand Synthesis SuperMix (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Real-time PCR was performed using the IQ SYBR Green supermix and the iCycler IQ-Real-Time detection system (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA). PCR primers for PEDF were synthesized as described (Cheung et al., 2006). β-Actin was analysed in the same run. Fluorescent measurements were recorded during each annealing step. The PCR quality and specificity were verified by melting curve analysis and gel electrophoresis.

Competitive binding and co-activator recruitment assays

ERα and ERβ competitive binding assays were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Serial dilutions of Rb1 (7.8–2 μM) were used to compete with Fluormone, a proprietary fluorescent oestrogen ligand, for binding to the LBD of recombinant human ERα or ERβ. The fluorescence polarization was measured by a PTI Fluorescence Lifetime Scanning Spectrometer. If Rb1 does not bind to the LBD of ERα or ERβ, no competition occurs and a relatively large ER/Fluormone complex forms, exhibiting a high polarization value. If Rb1 binds to ERα or ERβ, the Fluormone is displaced from the complex, resulting in low polarization values. Negative (without any ligand; 0% competition) and positive (1 mM E2; 100% competition) controls provided limits for the fluorescence polarization range. IC50 was defined as the concentration that caused a half-maximum shift in polarization. The equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd) was calculated as the concentration of the competing ligand occupying half of the binding sites in the absence of the tracer ligand. IC50 and Kd values were obtained by fitting the data from the competition studies to a one-site competition model and from the saturation studies to a one-site binding model, respectively (Blommel et al., 2004). Fluorescence-labeled co-activator containing consensus LxxLL (where x is any amino acid) motif was used to differentiate the agonist from the antagonist of ERβ (Ozers et al., 2005). Helix12 unblocks the co-activator cleft upon binding of agonist to the LBD. Competitive binding studies between Rb1 and the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) were carried out using a GR competitive binding assay, in which 1 mM dexamethasone served as a positive control.

Reporter gene assay

pERE-TA-SEAP reporter plasmids (0.5 μg well−1 of 24-well plate) or pTAL-SEAP (negative control) were used with Lipofectamine. pERE-TA-SEAP contains tandems of ERE linked to a downstream SEAP reporter gene. pTAL-SEAP is an identical plasmid but without the ERE. After transfection for 24 h, cells were treated and conditioned medium were harvested after further 24 h incubation. SEAP activity was assayed according to the manufacturer's protocol using the SEAP Fluorescence detection kit. The SEAP activity was measured as relative fluorescence intensity per μg of total cellular protein, and expressed as multiples of the untreated control.

The PEDF promoter region between positions −864 and +63 (Tombran-Tink et al., 2004) was transfected using Lipofectamine and the procedure carried out as directed by the manufacturer. The pSV-β-galactosidase plasmid was co-transfected as an internal control. Luciferase activity was measured using a luminometer (TD20/20, Turner Designs). Relative luciferase units (RLU) normalized to transfection efficiency were calculated as the ratio of luciferase activity to β-galactosidase activity and are presented as the mean±s.d. of three individual experiments, each with triplicate samples. The fold changes were calculated by comparison with the promoterless luciferase vector (pGL3-Basic).

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was repeated at least three times with essentially identical results and presented as mean±s.d. Statistical comparisons were carried out by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with Tukey's least significant difference t-test for post hoc analysis (GraphPad software, San Diego). P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Materials

Ginsenoside-Rb1 (Rb1) is a reference compound (purity >98%) purchased from the Division of Chinese Materia Medica and Natural Products, National Institute for the Control of Pharmaceutical and Biological Products (NICPBP), Ministry of Public Health, China. Phenol red-free medium 199, ECGS, heparin, GR antagonist RU486, dexamethasone (Dex), and the polyclonal anti-β-actin were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA). Charcoal/dextran-treated FBS was obtained from Hyclone (Logan, UT, USA). Diarylpropionitrile (DPN), propyl pyrazole triol (PPT), and the ER antagonist ICI 182,780 were obtained from Tocris Biosciences (Ellisville, MI, USA). Antibodies to ERα and ERβ were purchased from Upstate Biotechnology Inc. (Lake Placid, NY, USA), PEDF antibodies were from Bioproducts (Maryland, MD, USA). The peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Zymed (San Francisco, CA, USA). Growth factor-reduced Matrigel (GFR-Matrigel), pERE-TA-SEAP, and pGRE-TA-SEAP were from BD Biosciences (Palo Alto, CA, USA). ERα and ERβ competitive binding assays, GR competitive binding assay, and ER co-activator binding assay were from Invitrogen. siRNA for silencing ERβ (Cat. No. M-003402-02) was from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO, USA).

Results

Rb1 promotes the expression and secretion of PEDF in HUVEC

PEDF is a natural inhibitor of angiogenesis that plays a crucial role in maintaining the angiogenic balance (Dawson et al., 1999). To evaluate the possible effect of Rb1 on PEDF expression, HUVEC were stimulated with different concentrations (0–500 nM) of Rb1 for 24 h. Figure 1 shows that Rb1 dose-dependently induced PEDF protein expression in the cell lysate with the maximal effect being observed at a dose of 250 nM (Figure 1a). Consistently, media conditioned by these cells also showed enhanced secretion of PEDF (Figure 1b). The presence of a specific 50-kDa band indicated that PEDF was appropriately synthesized and processed.

Figure 1.

Rb1 regulated PEDF expression in HUVEC. HUVEC were incubated in culture medium supplemented with 20% charcoal-stripped FBS for 48 h, and, subsequently, were treated with vehicle only, or increasing concentrations of Rb1 (100–500 nM) for 24 h. (a) Cell lysate (40 μg) and (b) conditioned medium (100 μg) were analysed by western blot for the presence of PEDF protein. Immunoblotting for β-actin and staining of proteins by Coomassie blue were included as loading controls for (a and b), respectively. The signal intensity was determined by densitometry and expressed as the ratio of PEDF relative to β-actin or Coomassie blue for each sample (right panels). Experiments were repeated three times and data are shown as mean±s.d. *P<0.05 for Rb1-treated cells versus untreated control. PEDF, pigment epithelium-derived factor; HUVEC, human umbilical vein endothelial cells; FBS, fetal bovine serum.

To elucidate whether Rb1-induced PEDF secretion was transcriptionally controlled, mRNA expression of PEDF was measured by real-time PCR. Melting curve analysis yielded a single peak, and gel electrophoresis showed a single band (data not shown). Treatment of HUVEC with 250 nM Rb1 resulted in a significant upregulation of PEDF mRNA (Figure 2a). The fold-change in mRNA levels was comparable to that in protein levels (∼7-fold), suggesting that the increased PEDF protein expression may result from increased mRNA synthesis.

Figure 2.

Rb1 directly activated PEDF transcription. (a) Cells were incubated in culture medium supplemented with 20% charcoal-stripped FBS for 48 h, and then cultured in the presence of 250 nM Rb1 for 24 h. Changes in PEDF mRNA levels were determined by real-time PCR using primers specific for PEDF and β-actin. (b) Cells were transfected with 1 μg of reporter construct of PEDF promoter region from nucleotide −864 to +63 in the presence or absence of 250 nM Rb1. All cells were co-transfected with 0.5 μg of pSV-βGal as an internal control for transcription efficiency. The reporter activity, referred to as relative luciferase units (RLU), was calculated as the ratio of luciferase to β-galactosidase activity normalized by the RLU (=1) displayed by cells transfected with the pGL3-Basic vector. The results are obtained from three repeated experiments, and data are shown as mean±s.d. *P<0.05 for treated cells versus untreated control. PEDF, pigment epithelium-derived factor; FBS, fetal bovine serum.

Rb1 directly regulates PEDF gene transcription

To assess whether Rb1 causes transcriptional activation at the PEDF promoter, we transfected HUVEC with a luciferase reporter construct of the PEDF promoter region −864 to +63 and measured luciferase activity after treatment with 250 nM of Rb1. Luciferase activity was normalized according to the β-galactosidase activity and expressed as RLU to reflect the promoter activity. Transfection efficiency was >70% as determined using the green fluorescent protein. The results showed that the activity of PEDF promoter was strongly increased (3.5-fold) by Rb1 (P<0.05) (Figure 2b). These results clearly demonstrate a direct effect of Rb1 on the human PEDF gene promoter.

Rb1-induced anti-angiogenic actions involves PEDF in HUVEC

Next, we examined whether the anti-angiogenic activity of Rb1 was mediated via modulation of PEDF. Tube formation assay was employed because it is the most simple and classical angiogenesis assay in vitro and has been described as representing the multi-step process of angiogenesis involving cell adhesion, migration, and differentiation (Madri et al., 1988). As shown in Figure 3, endothelial cells aligned and formed tube-like network structures in the absence of Rb1, in contrast to a significant decrease in tube formation of HUVEC following treatment with 250 nM Rb1. The anti-angiogenic effect of Rb1 was completely reversed by the addition of PEDF-neutralizing antibody (P<0.05), confirming that Rb1 actions were mediated through PEDF and that the negative effect of PEDF on tube formation was specific. Importantly, conditioned media derived from Rb1-treated HUVEC (Rb1-CM) also led to a 4.6-fold decrease in the number of branch points, an effect that was markedly attenuated in the presence of the PEDF-neutralizing antibody but not control immunoglobulin G (IgG). The antibodies alone had no effect on tube formation. These data demonstrate, for the first time, a role for PEDF in mediating the anti-angiogenic activity of Rb1 in HUVEC.

Figure 3.

PEDF was involved in Rb1-mediated inhibition of endothelial tube formation. HUVEC (1 × 105 cells per well) were seeded in growth factor-reduced, Matrigel-coated, 24-well plate in phenol red-free medium 199 containing 1% charcoal-stripped FBS. Cells were treated with or without 250 nM Rb1 in the absence or presence of PEDF-neutralizing antibody (anti-PEDF). Conditioned medium derived from Rb1-stimulated HUVEC (Rb1-CM) was left untreated or pretreated with anti-PEDF or control IgG. Control cells were treated with anti-PEDF or IgG alone. Bottom panel, data represent the mean±s.d. of the number of branch points relative to the control, which was set to be 100%, counted in 12 microscopic fields of three independent experiments. Scale bar, 50 μm. *P<0.05 for treated cells versus untreated control. PEDF, pigment epithelium-derived factor; HUVEC, human umbilical vein endothelial cells; FBS, fetal bovine serum; IgG, immunoglobulin G.

ERα and ERβ expression of HUVEC

ER is a potential regulator of PEDF gene expression (Tombran-Tink et al., 1996; Cheung et al., 2006; Li et al., 2006) and the oestrogenic effect of Rb1 has been previously proposed (Lee et al., 2003; Cho et al., 2004). To investigate the possible role of ER in Rb1-induced anti-angiogenic activity, we first evaluated the expression of ERα and ERβ by western blot analysis and real-time PCR in HUVEC. Figure 4 reveals that the protein and mRNA of both subtypes were present in the cells, as described previously (Venkov et al., 1996). Rb1 treatment for 24 h did not alter ERα and ERβ expression (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Expression of ERα and ERβ in HUVEC. Western blot and real-time PCR were performed on HUVEC for ERα and ERβ protein expression and mRNA quantification. β-Actin was included as a loading control. ER, oestrogen receptor; HUVEC, human umbilical vein endothelial cells.

Rb1 is a functional ligand for ERβ but not for ERα or GR

Thereafter, a competitive ligand-binding assay was performed to study the specific binding of Rb1 to ERα and ERβ using proprietary fluorescent ligand (Fluormone)-recombinant human ER complexes. Displacement of Fluormone from the complex results in a decrease in fluorescence polarization. The shift in polarization is used to determine the specific affinity of that ligand for the respective receptor. The competitive ligand binding assays indicated that Rb1 is a specific ligand for ERβ, but not for ERα. The IC50 values for E2 and Rb1 were 15.18 nM (Kd=4.82 nM; R2=0.98) and 246.70 nM (Kd=70.36 nM; R2=0.99), respectively (Figure 5a). This value agrees well with the concentration of Rb1 (250 nM) that shows significant inhibitory effects on PEDF expression and angiogenesis (Figures 1, 2 and 3). Moreover, the binding was specific for ER because similar concentration (or even at a concentration 100-fold higher) of Rb1 could not displace Fluormone (Glucocorticoid) from the GR (data not shown). These results demonstrate that Rb1 is a selective agonist for ERβ, but not for ERα or GR.

Figure 5.

Competitive binding of Rb1 to ERβ, co-activator peptide recruitment, and reporter gene activation. (a) The competitive binding was determined by a fluorescence polarization-based assay using recombinant human ERα or ERβ, and E2 (1 mM) served as positive controls. (b) Fluorescent-labeled co-activator containing consensus LxxLL (where x is any amino acid) motif was used to differentiate the agonist from the antagonist of ERβ. Fluorescence polarization was expressed as millipolarization units (mP). Data represent the means from three different experiments. (C) HUVEC was transiently transfected with a reporter gene containing 2 × ERE. E2 (50 nM) and ICI 182,780 (ICI) (10 μM) were used as positive and negative controls. SEAP activity was measured as relative fluorescence intensity per microgram of total protein. The SEAP activity of the untreated control cells was defined as 1. Data represent mean±s.d. (n=3). *P<0.05 for treated cells versus untreated control. ER, oestrogen receptor; HUVEC, human umbilical vein endothelial cells; ERE, oestrogen responsive element; E2, 17β-oestradiol.

In the classical genomic pathway of oestrogen action, the nuclear hormone receptor–ligand complex undergoes a conformation change allowing the receptor to interact with ERE located on the promoter regions and to recruit coregulators for initiation of transcription of target genes (Gustafsson, 2000a). Using the co-activator recruitment assay, we showed that Rb1, like E2, induced interaction of ERβ with co-activator peptides (Figure 5b). In addition, Rb1 was able to activate ER transcription from a SEAP reporter gene (pERE-TA-SEAP) under the control of a promoter containing two copies of the ERE in HUVEC, showing a 2.1-fold induction over control and this efficacy was comparable with that of E2 (Figure 5c). Both E2 and Rb1 had no effect on pTAL-SEAP, a vector identical to pERE-TA-SEAP but without the ERE (data not shown). ICI 182,780, a specific ER antagonist, was used as a negative control. It was able to bind the LBD of ER but showed no recruitment of co-activator peptide or transactivation of the reporter gene (Figures 5b and c). These data further confirm that Rb1 can directly activate ERβ signaling.

The actions of Rb1 on PEDF expression and function are mediated via ERβ

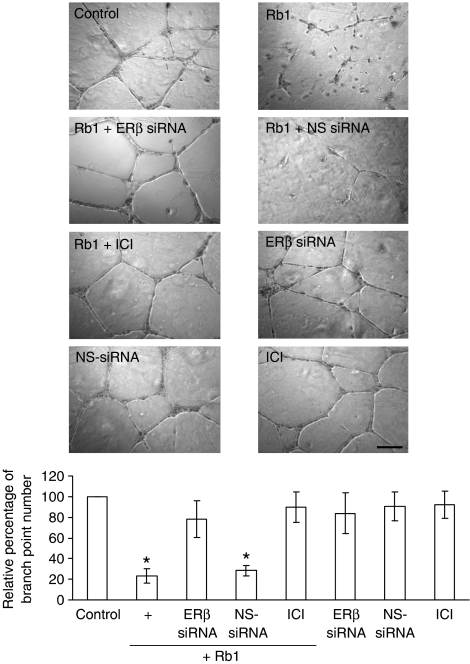

To study the involvement of ERβ in Rb1-induced PEDF activation, we examined the effect of the ERβ selective agonist DPN (100 nM) (Harrington et al., 2003) on PEDF expression. The results showed that DPN closely reproduced the response of Rb1 with a significant increase in the amount of PEDF mRNA (6.3-fold versus control) (Figure 6a). In contrast, the ERα selective agonist PPT did not increase PEDF expression (data not shown), suggesting the involvement of ERβ in the Rb1-induced anti-angiogenic action. To further define the role of ERβ in the Rb1 effects, we chose to deplete ERβ using siRNA. The efficacy of silencing ERβ was determined by immunoblotting (Figure 6b). Most importantly, reduced ERβ expression with siRNA markedly attenuated Rb1-induced PEDF expression (Figures 6c and d) as well as its effects on endothelial tube formation (Figure 7) when compared with cells transfected with non-specific siRNA. PEDF promoter activity was also reduced by ERβ siRNA, suggesting that the ER-mediated activation of PEDF occurs via a genomic pathway. These activities can also be specifically blocked by treatment with the specific ER antagonist ICI 182,780 (Figures 6 and 7), providing further support for the role of activated ER in mediating Rb1 action in these cells. The antagonist or siRNA alone had no effect (Figures 6 and 7). Together, these data indicate that ERβ is a critical mechanistic link in mediating the anti-angiogenic effects of Rb1 in HUVEC.

Figure 6.

Inhibition of ERβ suppressed Rb1-induced PEDF expression. (a) PEDF mRNA was assessed by real-time RT-PCR in untreated control cells or cells treated with Rb1, E2, or DPN. (b) Cells were transiently transfected with siRNA directed against ERβ (ERβ siRNA) or non-specific siRNA (NS-siRNA) as a control. ERα and ERβ expression levels were analysed by western blot. Changes in PEDF mRNA and protein were analysed by (c) real-time PCR and (d) western blot, respectively. Cells treated with a specific ER antagonist ICI 182,780 (ICI) were also analysed. Experiments were repeated three times, and data are shown as mean±s.d. *P<0.05 for treated cells versus untreated control. ER, oestrogen receptor; ERE, oestrogen responsive element; E2, 17β-oestradiol; RT-PCR, reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction; DPN, diarylpropionitrile; siRNA, small interfering RNA.

Figure 7.

Inhibition of ERβ attenuated Rb1-mediated inhibition of endothelial tube formation. HUVEC (1 × 105 cells per well) were seeded in growth factor-reduced, Matrigel-coated, 24-well plate in phenol red-free medium 199 containing 1% charcoal-stripped FBS. Cells were treated with or without 250 nM Rb1, in the absence or presence of ERβ siRNA, non-specific (NS)-siRNA, or ICI 182,780 (ICI). Control cells were treated with ERβ siRNA, NS-siRNA, or ICI alone. Bottom panel, data represent the mean±s.d. of the number of branch points relative to the control, which was set to be 100%, counted in 12 microscopic fields of three independent experiments. Scale bar, 50 μm. *P<0.05 for treated cells versus untreated control.

Discussion

The growth of solid tumours is highly dependent on angiogenesis. Thus, inhibition of angiogenesis has become a promising approach in anticancer therapy (Fan et al., 2006). Our data provide a molecular basis for the anti-angiogenic action of Rb1. Here we show for the first time that the Rb1 suppresses tube-like structure formation, and that this effect is mediated by activation of the potent anti-angiogenic protein PEDF under the control of ERβ, but not ERα. The clinical relevance of this observation was underpinned by the fact that Rb1 and its metabolite inhibited tumour angiogenesis in vivo (Sato et al., 1994; Shibata, 2001). In epidemiological case–control studies, ginseng was found to possess cancer prevention activities in various organ sites (Yun, 2003).

PEDF is one of the most potent inhibitors of angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo, an action clearly evident in tumour xenografts, tube-like structure formation, and corneal neovascularization (Dawson et al., 1999; Duh et al., 2002; Abe et al., 2004). Mice lacking PEDF exhibit increased vascularity in most organs (Folkman, 2004). In our study, the anti-angiogenic effects of Rb1, as demonstrated by inhibition of endothelial tubular networks formation when grown on a reconstituted basement membrane, were reversed with a PEDF-neutralizing antibody, strongly suggesting that PEDF is downstream to Rb1 action in HUVEC. The importance of PEDF as an angiomodulator is obvious from the fact that it targets only new vessel growth and spares the pre-existing vasculature and, as an endogenously produced molecule, PEDF is relatively non-toxic, although side effects might present at high doses (Ek et al., 2006).

Another novel observation presented here is the finding that PEDF is a direct target of ERβ. Rb1 causes transcriptional activation at the PEDF promoter. Since the ERβ agonist DPN, but not the ERα agonist PPT, induced a similar increase of the amount of PEDF mRNA, we proposed that the regulation of PEDF is ERβ-mediated. These studies represent the first demonstration that Rb1 induces PEDF expression through the transcriptional effect of ERβ, an interesting finding that now makes PEDF a target for both ER subtypes although its transcriptional response is likely to depend on the ER type and the ligand. In line with our present findings, E2 treatment of retinal Müller cells, which are known to be ERβ positive, has also been shown to upregulate PEDF mRNA expression (Li et al., 2006). On the contrary, in human ovarian surface epithelial cells where the main ER subtype is ERα (Brandenberger et al., 1998), E2 has been reported to repress PEDF gene expression (Cheung et al., 2006). Also, E2 could regulate gene transcription via other motifs in addition to the ERE, including activator protein-1, nuclear factor-κB, and cAMP-responsive element binding protein (Alexaki et al., 2006; Cascio et al., 2007) and their binding sites are present in the PEDF promoter. Whether these regulatory elements participate in ER-mediated transcriptional regulation of PEDF remains to be determined and is an area for further research. The mechanism for the differential ERα and ERβ-mediated transcriptional regulation of PEDF is unknown and again requires further study.

The oestrogenic effects of Rb1 have been previously hypothesized (Lee et al., 2003; Cho et al., 2004). In this study, we showed for the first time a direct effect of Rb1 on ER in human endothelial cells and that this effect was mediated by ERβ, rather than ERα. In competitive ligand-binding assays, Rb1 was able to displace a high-affinity fluorescent oestrogen ligand from human recombinant ERβ, but not ERα. Furthermore, the ability to recruit co-activator peptides to the receptor and the activation of the reporter gene have demonstrated that Rb1 can activate transcription from the consensus ERE motifs. Our results also demonstrated that GR showed no response to Rb1, providing further support for a specific role of activated ER in mediating its action.

The mechanism of the oestrogenic effect has been re-evaluated following the discovery of a second ER subtype, ERβ (Rubanyi et al., 1997). Studies in ERα knockout mice (Sudhir et al., 1997) and in the only known individual lacking functional ERα (Gustafsson, 2000b) point to a positive role for ERα in the regulation of angiogenesis. The impact of ERβ in this regard is less clear although several reports support the role of ERβ as a negative regulator of ERα (Pettersson and Gustafsson, 2001; Buteau-Lozano et al., 2002). However, a possible role for ERβ in inhibition of angiogenesis has been postulated, based on the evidence that E2 decreases the expression of the angiogenic factor VEGF in breast cancer cells transfected with ERβ (Garvin et al., 2006), as well as reduced angiogenesis of the MDA-MB-231 xenograft tumours which endogenously express ERβ (Doll et al., 2003). Our findings that Rb1 binds preferentially to ERβ, but not ERα, suggest that this ginsenoside may have potential pharmacological utility as a natural selective ER modulator with tissue-specific action. The potential advantage of tissue-specific action is the reduction of systemic side effects. Thus, ERβ has been shown to produce the beneficial effects of oestrogen on bone and the cardiovascular system without the undesirable effects of oestrogen on breast and endometrial proliferation (Pettersson and Gustafsson, 2001; Buteau-Lozano et al., 2002), which could possibly account for the reported favourable influence of ginseng in postmenopausal women and its anticancer effects (Kronenberg and Fugh-Berman, 2002; Lee et al., 2003).

In summary, the present study provides evidence supporting the postulated role of Rb1 as an inhibitor of angiogenesis and demonstrates the novel finding that inhibition of the formation of tube-like structures by endothelial cell cultures by Rb1 is mediated through PEDF via the ERβ subtype in HUVEC. These findings also provide further insights into the possible therapeutic use of Rb1, especially in cancer, where neovascularization is an important pathological component.

Acknowledgments

The present work was supported by Earmarked Research Grants (HKBU 2171/03M, HKBU2476/06M to RNSW, and HKU 7599/05M to ASTW) of the Research Grant Council, Hong Kong SAR Government.

Abbreviations

- Dex

dexamethasone

- DPN

diarylpropionitrile

- ER

oestrogen receptor

- E2

17β-oestradiol

- ERE

oestrogen responsive element

- GR

glucocorticoid receptor

- HUVEC

human umbilical vein endothelial cells

- LBD

ligand-binding domain

- PEDF

pigment epithelium-derived factor

- PPT

propyl pyrazole triol

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Abe R, Shimizu T, Yamagishi S, Shibaki A, Amano S, Inagaki Y, et al. Overexpression of pigment epithelium-derived factor decreases angiogenesis and inhibits the growth of human malignant melanoma cells in vivo. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:1225–1232. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63210-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexaki VI, Charalampopoulos I, Kampa M, Nifli AP, Hatzoglou A, Gravanis A, et al. Activation of membrane estrogen receptors induce pro-survival kinases. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2006;98:97–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blommel P, Hanson GT, Vogel KW. Multiplexing fluorescence polarization assays to increase information content per screen: applications for screening steroid hormone receptors. J Biomol Screen. 2004;9:294–302. doi: 10.1177/1087057104264420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandenberger AW, Tee MK, Jaffe RB. Estrogen receptor alpha (ER-alpha) and beta (ER-beta) mRNAs in normal ovary, ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma and ovarian cancer cell lines: down-regulation of ER-beta in neoplastic tissues. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:1025–1028. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.3.4788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buteau-Lozano H, Ancelin M, Lardeux B, Milanini J, Perrot-Applanat M. Transcriptional regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor by estradiol and tamoxifen in breast cancer cells: a complex interplay between estrogen receptors alpha and beta. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4977–4984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascio S, Bartella V, Garofalo C, Russo A, Giordano A, Surmacz E. Insulin-like growth factor 1 differentially regulates estrogen receptor-dependent transcription at estrogen response element and AP-1 sites in breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:3498–3506. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606244200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung LW, Au SC, Cheung AN, Ngan HY, Tombran-Tink J, Auersperg N, et al. Pigment epithelium-derived factor is estrogen sensitive and inhibits the growth of human ovarian cancer and ovarian surface epithelial cells. Endocrinology. 2006;147:4179–4191. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho J, Park W, Lee S, Ahn W, Lee Y. Ginsenoside-Rb1 from Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer activates estrogen receptor-alpha and -beta, independent of ligand binding. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:3510–3515. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DW, Volpert OV, Gillis P, Crawford SE, Xu HJ, Benedict W, et al. Pigment epithelium-derived factor: a potent inhibitor of angiogenesis. Science. 1999;285:245–248. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5425.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doll JA, Stellmach VM, Bouck NP, Bergh AR, Lee C, Abramson LP, et al. Pigment epithelium-derived factor regulates the vasculature and mass of the prostate and pancreas. Nat Med. 2003;9:774–780. doi: 10.1038/nm870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duda RB, Zhong Y, Navas V, Li MZ, Toy BR, Alavarez JG. American ginseng and breast cancer therapeutic agents synergistically inhibit MCF-7 breast cancer cell growth. J Surg Oncol. 1999;72:230–239. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9098(199912)72:4<230::aid-jso9>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duh EJ, Yang HS, Suzuma I, Miyagi M, Youngman E, Mori K, et al. Pigment epithelium-derived factor suppresses ischemia-induced retinal neovascularization and VEGF-induced migration and growth. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:821–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ek ET, Dass CR, Choong PF. PEDF: a potential molecular therapeutic target with multiple anti-cancer activities. Trends Mol Med. 2006;12:497–502. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan TP, Yeh JC, Leung KW, Yue PY, Wong RN. Angiogenesis: from plants to blood vessels. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27:297–309. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman J. Endogenous angiogenesis inhibitors. APMIS. 2004;112:496–507. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2004.apm11207-0809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garvin S, Ollinger K, Dabrosin C. Resveratrol induces apoptosis and inhibits angiogenesis in human breast cancer xenografts in vivo. Cancer Lett. 2006;231:113–122. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson JA. Novel aspects of estrogen action. J Soc Gynecol Invest. 2000a;7:S8–S9. doi: 10.1016/s1071-5576(99)00060-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson JA. New insights in oestrogen receptor (ER) research – the ERbeta. Eur J Cancer. 2000b;36 Suppl. 4:S16. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00206-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington WR, Sheng S, Barnett DH, Petz LN, Katzenellenbogen JA, Katzenellenbogen BS. Activities of estrogen receptor alpha- and beta-selective ligands at diverse estrogen responsive gene sites mediating transactivation or transrepression. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2003;206:13–22. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(03)00255-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helms S. Cancer prevention and therapeutics: Panax ginseng. Altern Med Rev. 2004;9:259–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronenberg F, Fugh-Berman A. Complementary and alternative medicine for menopausal symptoms: a review of randomized, controlled trials. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:805–813. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-10-200211190-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YJ, Jin YR, Lim WC, Park WK, Cho JY, Jang S, et al. Ginsenoside-Rb1 acts as a weak phytoestrogen in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Arch Pharm Res. 2003;26:58–63. doi: 10.1007/BF03179933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Tang Y, Li F, Turner S, Li K, Zhou X, et al. 17beta-estradiol (betaE2) protects human retinal Muller cell against oxidative stress in vitro: evaluation of its effects on gene expression by cDNA microarray. Glia. 2006;53:392–400. doi: 10.1002/glia.20291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madri JA, Pratt BM, Tucker AM. Phenotypic modulation of endothelial cells by transforming growth factor-beta depends upon the composition and organization of the extracellular matrix. J Cell Biol. 1988;106:1375–1384. doi: 10.1083/jcb.106.4.1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozers MS, Ervin KM, Steffen CL, Fronczak JA, Lebakken CS, Carnahan KA, et al. Analysis of ligand-dependent recruitment of coactivator peptides to estrogen receptor using fluorescence polarization. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:25–34. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersson K, Gustafsson JA. Role of estrogen receptor beta in estrogen action. Annu Rev Physiol. 2001;63:165–192. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhim H, Kim H, Lee DY, Oh TH, Nah SY. Ginseng and ginsenoside Rg3, a newly identified active ingredient of ginseng, modulate Ca2+ channel currents in rat sensory neurons. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;436:151–158. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01613-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risau W. Mechanisms of angiogenesis. Nature. 1997;386:671–674. doi: 10.1038/386671a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubanyi GM, Freay AD, Kauser K, Sukovich D, Burton G, Lubahn DB, et al. Vascular estrogen receptors and endothelium-derived nitric oxide production in the mouse aorta. Gender difference and effect of estrogen receptor gene disruption. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:2429–2437. doi: 10.1172/JCI119426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Mochizuki M, Saiki I, Yoo YC, Samukawa K, Azuma I. Inhibition of tumor angiogenesis and metastasis by a saponin of Panax ginseng, ginsenoside-Rb2. Biol Pharm Bull. 1994;17:635–639. doi: 10.1248/bpb.17.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta S, Toh SA, Sellers LA, Skepper JN, Koolwijk P, Leung HW, et al. Modulating angiogenesis: the yin and the yang in ginseng. Circulation. 2004;110:1219–1225. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000140676.88412.CF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata S. Chemistry and cancer preventing activities of ginseng saponins and some related triterpenoid compounds. J Korean Med Sci. 2001;16 Suppl:S28–S37. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2001.16.S.S28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudhir K, Chou TM, Messina LM, Hutchison SJ, Korach KS, Chatterjee K, et al. Endothelial dysfunction associated with a disruptive mutation in the estrogen receptor gene. Lancet. 1997;349:1146–1147. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)63022-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tombran-Tink J. The neuroprotective and angiogenesis inhibitory serpin, PEDF: new insights into phylogeny, function, and signaling. Front Biosci. 2005;10:2131–2149. doi: 10.2741/1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tombran-Tink J, Lara N, Apricio SE, Potluri P, Gee S, Ma JX, et al. Retinoic acid and dexamethasone regulate the expression of PEDF in retinal and endothelial cells. Exp Eye Res. 2004;78:945–955. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2003.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tombran-Tink J, Mazuruk K, Rodriguez IR, Chung D, Linker T, Englander E, et al. Organization, evolutionary conservation, expression and unusual Alu density of the human gene for pigment epithelium-derived factor, a unique neurotrophic serpin. Mol Vis. 1996;2:11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkov CD, Rankin AB, Vaughan DE. Identification of authentic estrogen receptor in cultured endothelial cells. A potential mechanism for steroid hormone regulation of endothelial function. Circulation. 1996;94:727–733. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.4.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang A, Wang CZ, Wu JA, Osinski J, Yuan CS. Determination of major ginsenosides in Panax quinquefolius (American ginseng) using high-performance liquid chromatography. Phytochem Anal. 2005;16:272–277. doi: 10.1002/pca.838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue PY, Wong DY, Wu PK, Leung PY, Mak NK, Yeung HW, et al. The angiosuppressive effects of 20(R)-ginsenoside Rg3. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;72:437–445. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun TK. Experimental and epidemiological evidence on non-organ specific cancer preventive effect of Korean ginseng and identification of active compounds. Mutat Res. 2003;523–524:63–74. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(02)00322-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S, Zou K, Fushimi H, Cal S, Komatsu K. Comparative study on triterpene saponins of Ginseng drugs. Planta Med. 2004;70:666–677. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-827192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]