Abstract

The discovery of fetal mRNA transcripts in the maternal circulation holds great promise for noninvasive prenatal diagnosis. To identify potential fetal biomarkers, we studied whole blood and plasma gene transcripts that were common to 9 term pregnant women and their newborns but absent or reduced in the mothers postpartum. RNA was isolated from peripheral or umbilical blood and hybridized to gene expression arrays. Gene expression, paired Student’s t test, and pathway analyses were performed. In whole blood, 157 gene transcripts met statistical significance. These fetal biomarkers included 27 developmental genes, 5 sensory perception genes, and 22 genes involved in neonatal physiology. Transcripts were predominantly expressed or restricted to the fetus, the embryo, or the neonate. Real-time RT-PCR amplification confirmed the presence of specific gene transcripts; SNP analysis demonstrated the presence of 3 fetal transcripts in maternal antepartum blood. Comparison of whole blood and plasma samples from the same pregnant woman suggested that placental genes are more easily detected in plasma. We conclude that fetal and placental mRNA circulates in the blood of pregnant women. Transcriptional analysis of maternal whole blood identifies a unique set of biologically diverse fetal genes and has a multitude of clinical applications.

Introduction

The dynamic nature of mRNA transcripts may provide invaluable information on fetal gene expression and fetal and maternal health during pregnancy. Poon et al. (1) were the first to demonstrate that fetal expressed genes could be used for noninvasive prenatal diagnosis by identifying male-specific fetal mRNA transcripts in maternal plasma. Unlike fetal DNA, which increases proportionately in maternal plasma throughout gestation (2), mRNA transcripts vary in their expression during each trimester of pregnancy (3, 4). The previous limitations associated with the identification of fetal DNA in maternal plasma, including dependence on male gender or unique paternal polymorphisms, are theoretically eliminated with the use of mRNA transcripts.

To date, several placental and fetal mRNA transcripts have been identified in maternal plasma. Using real-time quantitative RT-PCR amplification, Ng et al. showed that human chorionic gonadotropin β subunit (hCGB), human placental lactogen (PL), and corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) transcripts could be detected in maternal plasma (5). Each gene has a pattern of expression that depends on gestational age. Fetal-derived γ-globin transcripts are elevated in the maternal circulation following elective termination of pregnancy (6). Microarray analysis has identified clinically useful placental transcripts for noninvasive fetal gene profiling (7), such as elevated CRH in preeclampsia (8). Each of these placental and/or fetal markers is limited in its scope and restricts our overall understanding of fetal development, fetal pathology, and complications of pregnancy.

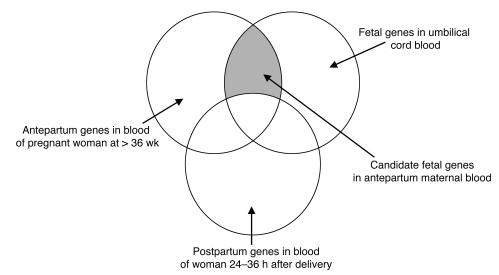

In the present study, we utilized gene expression microarrays to perform transcriptional analyses of maternal and fetal whole blood (9). Since fetal-derived mRNA is rapidly cleared from maternal circulation following delivery (10, 11), antepartum and postpartum samples were compared with paired newborn umbilical cord blood samples to identify unique fetal biomarkers in maternal whole blood. Our hypothesis was that if specific gene transcripts were detected in pregnant women prior to delivery as well as in their infants’ cord blood, yet were significantly reduced or absent in maternal blood within 24 to 36 hours of delivery, these gene transcripts could theoretically originate from the fetus (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A Venn diagram depicting presumed fetal gene transcripts detected in antepartum maternal blood.

Those gene transcripts that were detected in both the antepartum mother and fetus, but were not seen in the postpartum samples were targeted as unique fetal markers.

In our original sample set (n = 6), a unique subset of presumed fetal transcripts emerged that differed from previously published maternal plasma profiles (7). Therefore an additional subset of pregnant women and their infants (n = 3) were enrolled. Whole blood and plasma samples were obtained for comparative microarray analyses to better understand the biology of circulating fetal nucleic acids in the maternal circulation.

Results

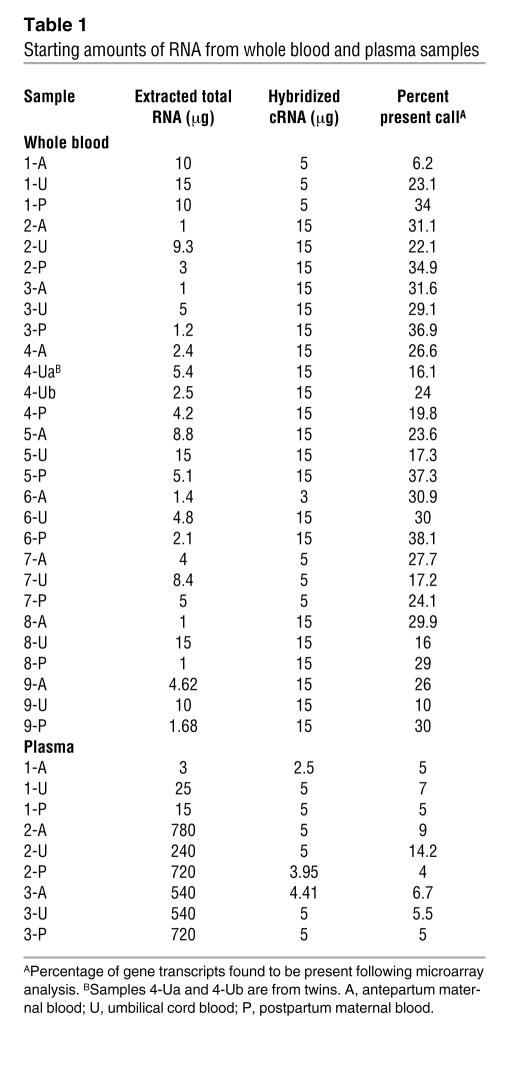

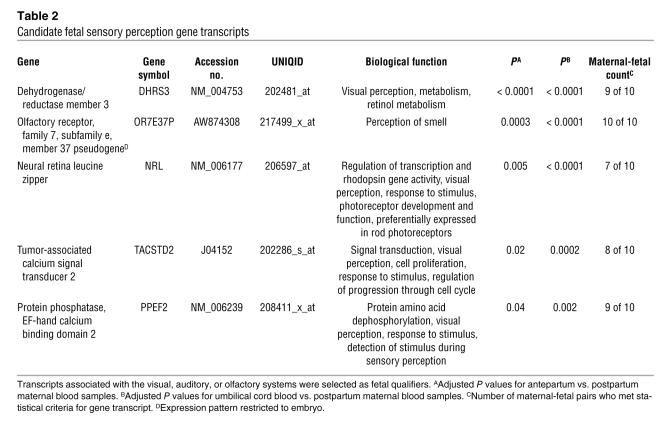

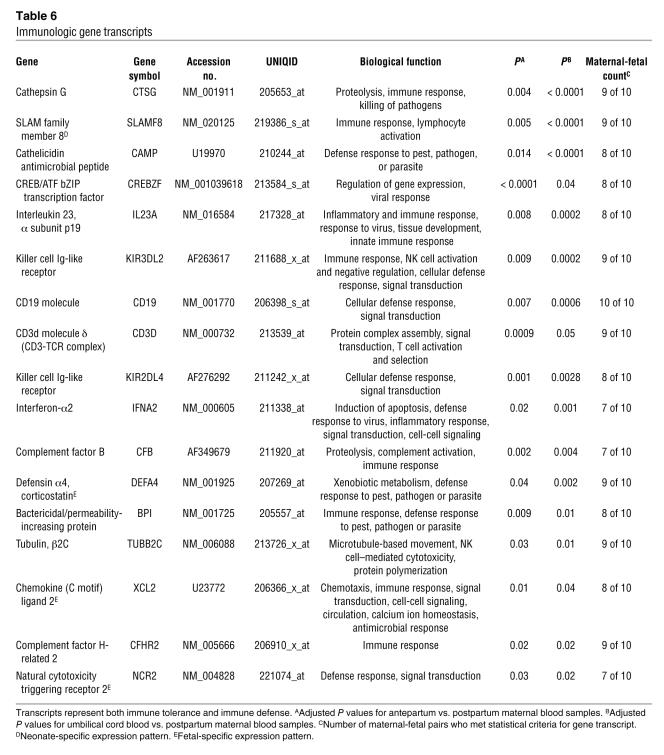

In each whole blood sample (n = 28), the starting amounts of total isolated RNA varied from 1 to 15 μg; 3 to 15 μg of fragmented complementary RNA (cRNA) was hybridized onto microarrays (Table 1). Mean percent present call (percentage of gene transcripts found to be present following microarray analysis) count was 26% (range, 6.2% to 38.1%). Following paired Student’s t test analysis, 157 transcripts met statistical criteria (P < 0.05) as candidate fetal genes (Supplemental Table 1; supplemental material available online with this article; doi:10.1172/JCI29959DS1). Each transcript was evaluated for its functional role, developmental pattern of expression, and participation in key biological pathways. This resulted in a smaller subset of genes (n = 71) in which the transcript was involved in a developmental process (e.g., ROBO4); derived from fetal, placental, or male tissue (e.g., PLAC1); or associated with a physiological newborn response (e.g., NPR1) or had its expression limited to or highly associated with a fetus or neonate (e.g., GDF9) (Tables 2–6). Within this subset, there were 27 developmental genes (musculoskeletal, epidermal, and nervous system), 5 sensory perception genes (olfactory and visual), 22 genes involved in fetal physiologic function or expressed predominantly in fetal, neonatal, placental, or male tissues, and 17 immune defense genes. One gene transcript, AFFX-BioDn-3_at, a spiked control, also met statistical criteria. Presumably its presence in our list of qualifiers is explained by the expected 5% false discovery rate.

Table 1 .

Starting amounts of RNA from whole blood and plasma samples

Table 2 .

Candidate fetal sensory perception gene transcripts

Table 6 .

Immunologic gene transcripts

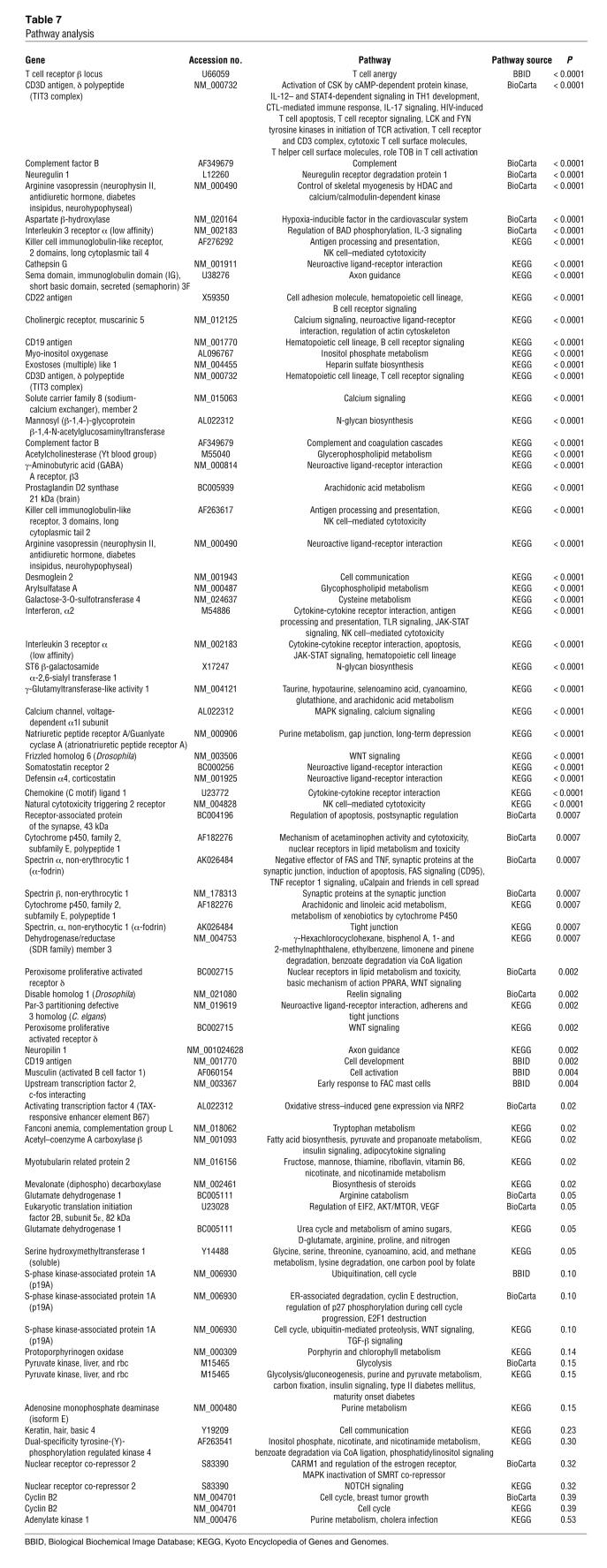

Pathway analysis identified transcripts associated with receptor proteins, antigens, and intrinsic membrane proteins. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway analysis suggested that transcripts involved in T cell biology were highly abundant. These included the CD3D antigen, CD19 antigen, CD22 antigen, and CD123 IL-3 receptor (P < 0.001). Biological Biochemical Image Database and BioCarta pathway analyses showed similar results (Table 7).

Table 7 .

Pathway analysis

Real-time RT-PCR amplification was performed on 5 of the 9 whole blood sample sets to confirm the presence of 4 gene transcripts detected on microarrays (GAPDH; defensin α1 [DEFA1], T cell receptor β variable 19 [TRBV19]; and myosin light polypeptide 4, alkali, atrial, embryonic [MYL4]). Genes were chosen randomly from an initial list of qualifiers derived from the first 6 subjects studied. There was 100% concordance between genes detected with real-time RT-PCR amplification and with microarray hybridization (Supplemental Table 2).

Initially, 10 commercially available single SNP assays were performed on cDNA synthesized from the original maternal and umbilical cord whole blood samples. Genotyping analysis of 5 women and their infants for 10 SNPs identified 1 SNP (CD19 rs2904880) within an antepartum sample that was identical to the umbilical cord genotype, yet differed from the maternal postpartum genotype. To further substantiate our findings, an additional 10 women, representing 11 maternal-fetal pairs (one set of dizygotic twins), were enrolled in our study for the sole purpose of SNP analysis. Both genomic DNA and total RNA were obtained from each subject at the established time points. In addition to CD19, a SNP analysis was performed for the gene KIR3DL2. There were 4 informative maternal-fetal genotypes; 2 revealed evidence of fetal RNA trafficking for KIR3DL2 (Supplemental Table 3).

In each plasma sample (n = 9), the starting amount of total isolated RNA varied from 3 to 780 ng; 2.5 to 5 μg of fragmented cDNA was hybridized onto microarrays (Table 1). The mean percent present call count for plasma cDNA was 6.8% (range, 4% to 14.2%). Following paired 2-tailed Student’s t test analysis, 175 transcripts met statistical criteria (Supplemental Table 4). Again, a spiked control, AFFX-r2-Bs-dap-5_at, met statistical significance.

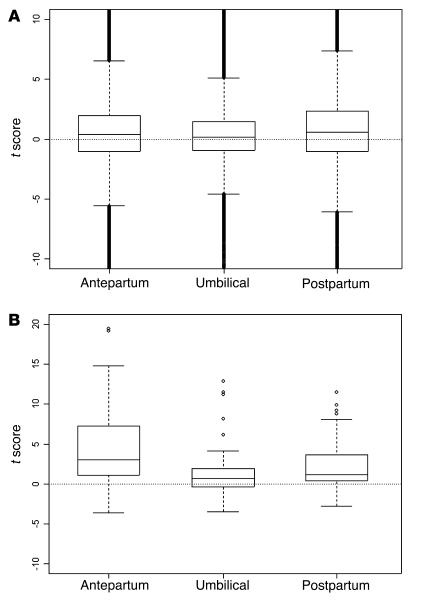

Overall, comparative analyses of whole blood and plasma transcripts located on the microarrays showed a range of differences (Figure 2A). Still, the interquartile range of the paired t scores contained 0 in all 3 cases, consistent with the fact that fewer than half the transcripts changed significantly in either direction between whole blood and plasma. However, in a set of 50 previously identified genes expressed in term placenta (7), 30 were shown to have significantly higher expression (adjusted P < 0.05) in antepartum plasma compared with corresponding antepartum whole blood using a paired 2-tailed Student’s t test. A χ2 test showed that this was significantly higher than would be expected compared with the observed rate (20%) for the full arrays (P < 0.00001). This contrasts strongly with the same analysis for the umbilical and postpartum comparisons, for which the differences in expression of this 50-gene set between whole blood and plasma were consistent with the distribution on the entire arrays (P = 0.45 and 0.16, respectively). The t score distribution for each of these comparisons in the 50-gene set is shown in Figure 2B.

Figure 2. Boxplots of paired t scores comparing gene expression in plasma and whole blood samples.

The boxes mark the first quartile, median, and third quartile of the t scores for each comparison. Vertical dotted lines represent t scores within 1.5 times the interquartile range. Positive t scores represent transcripts higher in plasma samples; negative t scores represent transcripts higher in whole blood. (A) Distribution of paired t scores for all 22,283 transcripts measured in antepartum, umbilical cord, and postpartum samples. What appear to be bold vertical lines are actually numerous dots. (B) Distribution of paired t scores for 50 previously identified placental transcripts. Dots indicate outliers.

Discussion

This study used transcriptional analyses to detect unique fetal biomarkers in maternal whole blood. Identification of these transcripts relied on primary data mining using commercially available software (NetAffx Analysis Center; Affymetrix), publicly available databases (OMIM and Entrez Gene), and publicly available expression profiles (UniGene). Pathway analysis was performed on Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) (12). This extensive and stringent analysis allowed us to identify presumably fetal gene transcripts that not only met statistical criteria but also proved biologically plausible through expression, functional, and pathway analyses.

Our results were both surprising and encouraging. By sampling maternal blood late in pregnancy, we identified specific gene transcripts that appeared to be associated with a fetus preparing to transition from the in utero environment. Sensory perception genes, particularly of the visual system, were upregulated in the term fetus and detected in the antepartum mother (Table 2). This was unexpected. Visual pathway genes included the neural retina leucine zipper (NRL), which is preferentially expressed in rod photoreceptors and is essential for photoreceptor development and function, and dehydrogenase/reductase member 3 (DHRS3), which is involved in visual perception and retinol metabolism.

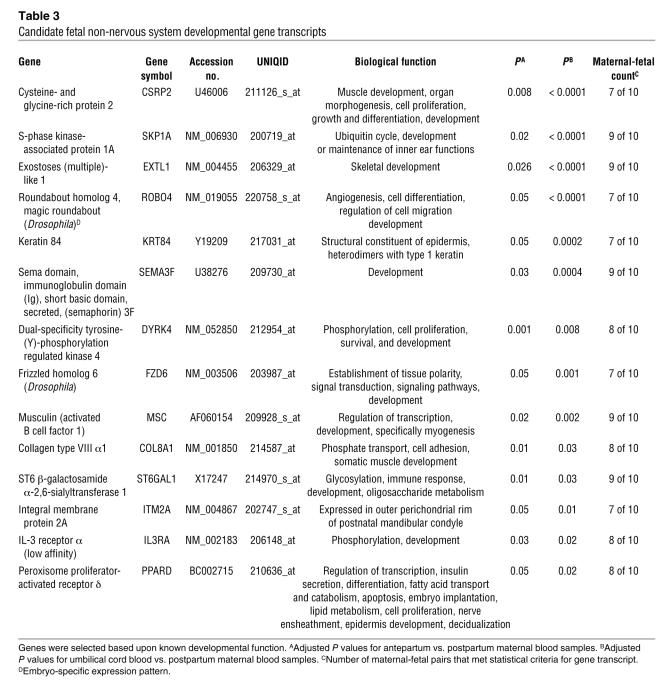

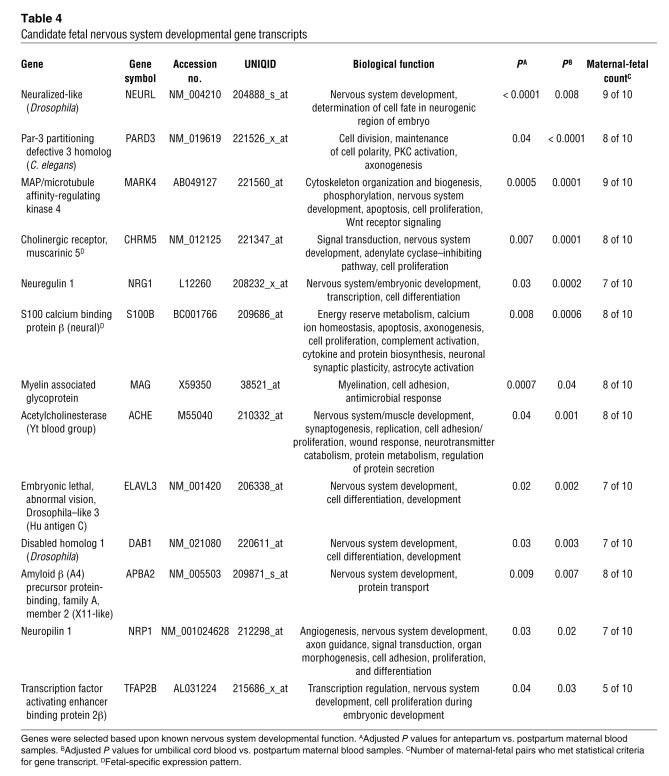

Developmental genes from the embryonic, muscular, skeletal, epidermal, and nervous systems were also identified (Tables 3 and 4). The nervous system genes constituted approximately half (48%) of the genes in this group (Table 4). Though subsequent studies profiling fetal developmental genes throughout pregnancy must be performed, it is interesting that neurodevelopmental genes predominate. It is well documented that near-term infants (32 to 36 weeks) may suffer from complications due to immaturity of the nervous system, presenting clinically as apnea of prematurity or an uncoordinated suck-swallow reflex. Thus it makes physiological sense that term fetuses would be upregulating neurodevelopmental transcripts.

Table 3 .

Candidate fetal non-nervous system developmental gene transcripts

Table 4 .

Candidate fetal nervous system developmental gene transcripts

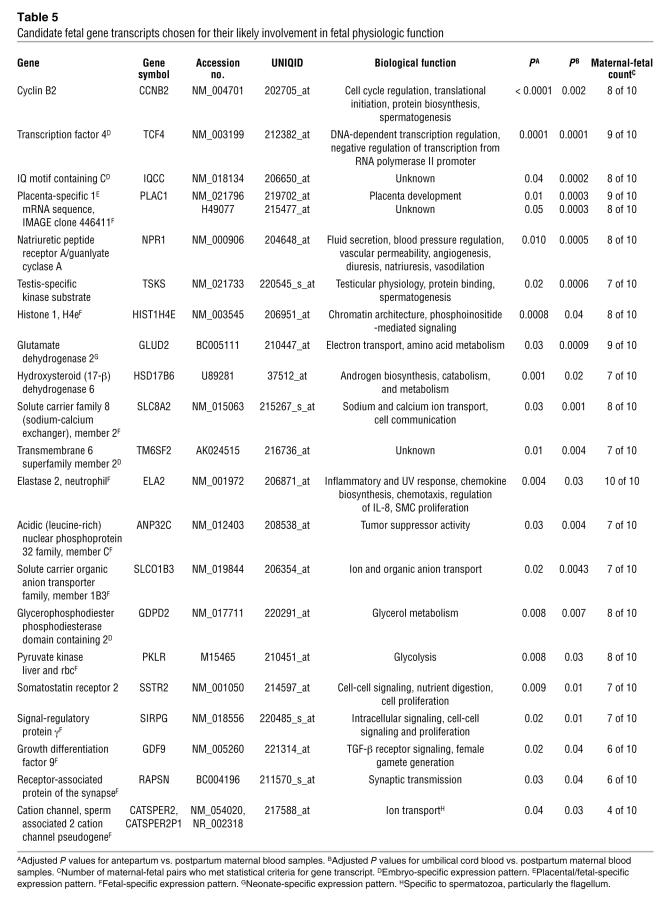

Several candidate fetal-derived genes of interest were also identified, based upon their tissue expression pattern or a probable neonatal physiological response (Table 5). Of particular interest were natriuretic peptide receptor A (NPR1) and S100 calcium binding protein β (neural) (S100B). NPR1 is likely responsible for the physiologic diuresis that occurs over the first 24 to 48 hours in all neonates, while S100B is involved in neurodevelopment. Overexpression of S100B has been associated with an increased susceptibility to perinatal hypoxia-ischemia in mice (13). This gene may be of interest for future studies, particularly in infants at risk for hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, a severe and often fatal disease.

Table 5 .

Candidate fetal gene transcripts chosen for their likely involvement in fetal physiologic function

Immune-mediated gene transcripts, several of which are specifically expressed in the fetus or neonate, were upregulated (Table 6). Given the intricate and delicate immune balance that must exist between a pregnant woman and her fetus (14, 15), this was not surprising. However, the immune gene transcripts identified in this study were not involved in immune tolerance but rather included genes that were involved with a host’s ability to mount an inflammatory response (complement factor B [CFB], natural cytotoxicity triggering receptor 2 [NCR2], and SLAM family member 8 [SLAMF8]) and its ability to defend against bacteria, fungi, and viruses (bactericidal/permeability increasing protein [BPI], defensin α4, corticostatin [DEFA4], cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide [CAMP], cation channel, sperm associated 2 cation channel pseudogene [CATSPER2,CATSPER2P1], and testis-specific kinase substrate [TSKS]). Additionally, independent pathway analysis revealed an abundance of transcripts associated with T cells. This finding was also intriguing given that the thymus gland, the major regulator of all T cells, is much more prominent and active in the neonate compared with the mother. Though none of these genes can be considered exclusively fetal in origin, it again appears that profiling a term infant reveals upregulation of gene transcripts essential for fetal-to-newborn transition.

There are 2 statistically significant transcripts that appear to be associated with male gender (Table 5). The 2 gene transcripts (cation channel, sperm associated 2 cation channel pseudogene and testis-specific kinase substrate) are either expressed in spermatozoa or involved in spermatogenesis. Neither of these transcripts maps to the Y chromosome. It may be surprising, given the predominance of male infants in our study (70%), that more gender-specific transcripts do not appear on our list. However, there are only 47 Y-chromosome specific transcripts on the Affymetrix HGU133a microarray, and only 5 of these are expressed at higher levels in male infants than in female infants in our study, which limits our ability to detect differences in gender-specific genes in the antepartum samples. Finally, given the small number (n = 3) of female infants in this study, there was inadequate power to confirm any sex-specific differences in the antepartum samples.

The presence of fetal-specific mRNA sequences was confirmed with multiple techniques. Not only were individual transcripts identified on microarrays confirmed by real-time RT-PCR amplification (Supplemental Table 2), but there was also an independent SNP analysis that identified 3 distinct fetal transcripts for 2 different genes in maternal antepartum blood (Supplemental Table 3). Our detection of 3 unique fetal SNPs from only 5 possible informative mother-infant combinations substantiates our work and provides definitive proof that biologically diverse fetal gene transcripts are entering the maternal circulation. Additionally, the UniGene analysis performed on the 157 statistically significant genes identified 17 transcripts predominantly expressed in the fetus, 5 transcripts predominantly expressed in the embryo, 2 transcripts predominantly expressed in the neonate, and 1 gene whose expression was restricted to the embryo.

Maternal and umbilical cord whole blood samples were the source of RNA for this study. Notably, whole blood is cellular and fetal cells persist for decades within the postpartum mother (16, 17). However, the identification of fetal genes in our study was dependent upon their absence in maternal postpartum samples and is likely not representative of prior pregnancies. The use of whole blood is also known to interfere with microarray hybridization rates. Although there are commercially available kits to reduce the amount of globin genes found in whole blood, we were unable to utilize such kits because they selectively reduce β- and α-globin genes, not the predominantly fetal γ-globin gene. Thus globin reduction of this sample set would result in a preferential reduction in the maternal samples only. Our results indicate that non–globin-reduced whole blood may have mild interference with the hybridization process. Our mean percent present call was 26%, which is lower than generally established mean (40% to 45%) using the same techniques (18). Additionally, blood samples were obtained over an extended time period, resulting in the use of microarrays from several different lots. While varying lots of microarrays may increase variability of findings, it will minimize the chance of a bias or systematic error associated with a single lot (19). Finally, recent literature has emerged demonstrating the reliability and reproducibility of a single microarray, and therefore no arrays were run in multiples (20).

The overwhelming majority of the literature examining fetal nucleic acid trafficking cites the placenta as the major source of fetal transcripts and utilizes plasma for their detection (21). Although some of the gene transcripts identified in this whole blood analysis were expressed in placental tissue, including placental-specific 1 (PLAC1), we did not identify other previously documented placental transcripts (PL, CRH, or hCGB) in maternal whole blood. This was both surprising and unexpected and resulted in additional studies in a subset of women and their infants who had comparative whole blood and plasma analyses. Overall, the distributions of t scores represented in paired gene expression differences between whole blood and plasma did not appear to be too strongly biased. However, when specific genes were targeted, a different profile emerged. A number of placental genes previously identified in maternal plasma were present in the antepartum plasma samples but continued to elude detection in corresponding whole blood. Identification of well-established placental genes within our plasma samples validates the work of previous authors and substantiates our own plasma microarray data despite our low hybridization rate. This result suggests that placental transcripts are more readily detectable in the maternal circulation from plasma than from whole blood. The discrepancy seen between gene expression profiles in whole blood and plasma raises important questions regarding the biological mechanisms of fetal nucleic acid trafficking.

In summary, fetal as well as placental mRNAs circulate in the blood of pregnant women. This report illustrates what we believe to be a novel approach to noninvasively monitor the developing fetus. Our results have been confirmed by multiple methods. Transcriptional analysis of maternal whole blood identifies a unique set of biologically diverse fetal genes not previously recognized, which may differ from comparable plasma analysis, and suggests fetal upregulation of pathways necessary for extrauterine life. The transcripts identified can serve as a baseline to compare fetuses affected by a variety of pathologic conditions and will have a multitude of important clinical applications in prenatal diagnosis, perinatology, and neonatology.

Methods

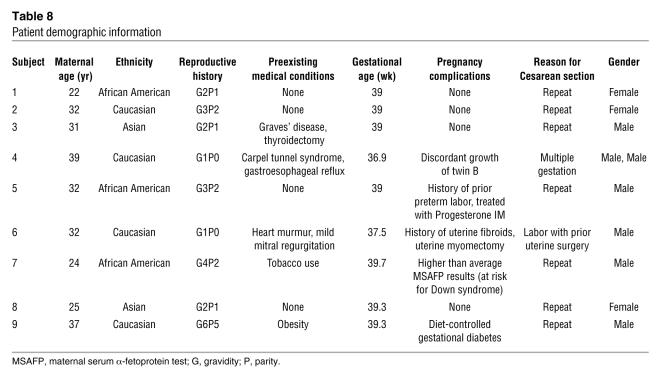

Subjects.

All pregnant women participating in this study presented to the Labor and Delivery Unit at Tufts — New England Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts, USA, at 36 weeks’ or more gestation for a scheduled cesarean section. Cesarean section deliveries were chosen for ease of sample attainment and to provide relatively uniform delivery conditions. Informed consent was obtained according to the protocol approved by the hospital’s Institutional Review Board. Nine women and 10 infants (1 twin gestation) participated in this study. In the first 6 study participants, only whole blood was obtained; in the subsequent subjects, both whole blood and plasma were obtained. A total of 37 (9 antepartum whole blood, 3 antepartum plasma, 9 postpartum whole blood, 3 postpartum plasma, 10 newborn whole blood, 3 newborn plasma) microarrays comprise the data set. One woman had undergone in vitro fertilization; the other pregnancies were conceived naturally. All other clinical and demographic details of study subjects are given in Table 8.

Table 8 .

Patient demographic information

RNA whole blood isolation.

Whole blood samples (7.5 cc) were obtained in 3 PaxGene (PreAnalytiX) tubes immediately prior to cesarean delivery and 24 to 36 hours postpartum and from the corresponding umbilical cord(s). Samples were stored at room temperature for 6 to 36 hours prior to RNA extraction in accordance with the PaxGene blood RNA kit (PreAnalytiX) manufacturer’s protocol. During extraction, on-column DNase digestion (RNase-Free DNase Set; Qiagen) was performed to eliminate DNA contamination. After final elution of extracted total RNA, 2.0 μl from each sample were analyzed on the Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent) to assess the quantity and purity of each sample. Only samples with clear peaks at ribosomal 18S and 28S that had a minimum starting amount of 1 μg total RNA met our quality and quantity criteria for subsequent amplification (Table 1).

RNA plasma isolation.

Whole blood was collected in 10-cc EDTA Vacutainer blood tubes (BD). Blood samples underwent an initial spin at 1,600 g for 10 minutes at 4°C. Harvested plasma was then transferred into microcentrifuge tubes and underwent an additional spin at 15,350 g for 10 minutes at 4°C to eliminate any residual cells. Plasma extraction was performed in accordance with previously published reports (22). Total RNA was eluted in 60 μl of RNase-free water. Quantity and quality of extracted total plasma RNA was assessed with the Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent) prior to amplification.

RNA whole blood amplification.

Extracted total RNA from whole blood was amplified according to the Eberwine protocol (23) with the use of the commercially available One Step Amplification Kit (Affymetrix). Amplified cRNA was again assessed with the Bioanalyzer 2100 for purity and quantity prior to fragmentation. Globin reduction was not performed on any sample.

RNA plasma amplification.

Extracted total RNA from plasma was amplified with the WT–Ovation Pico RNA Amplification System (NuGEN Technologies Inc.) in accordance with manufacturer’s protocol. Amplified cDNA was assessed with the Bioanalyzer 2100 for purity and quantity. Fragmentation and biotinylation occurred with the FL–Ovation cDNA Biotin Module v2 (NuGEN Technologies Inc.) per the manufacturer’s protocol.

Microarray hybridization, staining, and scanning.

Approximately 15 μg of amplified and labeled cRNA from whole blood and 5 μg of amplified and labeled cDNA from plasma samples were fragmented and hybridized onto GeneChip Human Genome U133A microarrays (Affymetrix) (Table 7). Hybridization quantities of whole blood cRNA and plasma cDNA were based on each respective amplification protocol. Following hybridization, each array was washed and stained in the GeneChip Fluidics Station 400 (Affymetrix). Each array was used once. Arrays were then scanned with the GeneArray Scanner (Affymetrix), and initial analysis was performed using the GeneChip Microarray Suite 5.0 (Affymetrix).

Real-time RT-PCR.

Confirmatory 1-step real-time RT-PCR was done on the extracted total RNA from 5 of the original 6 whole blood sample sets for 4 genes identified on the microarrays. The genes identified were GAPDH, DEFA1, TRBV19, and MYL4. All experiments were performed on the PerkinElmer Applied Biosystems 7700 Sequence Detector with the TaqMan One-Step RT-PCR Master Mix Reagents Kit (Applied Biosystems Inc.) as previously described (24).

The amplification primers and probes were as follows: GAPDH forward, 5′-GAAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGTC-3′, GAPDH reverse, 5′-GAAGATGGTGATGGGATTTC-3′, GAPDH probe, 5′-(6-FAM)-CAAGCTTCCCGTTCTCAGCC-(TAMRA)-3′; TRBV19 forward, 5′-GGCCACCTTCTGGCAGAA-3′, TRBV19 reverse, 5′-AGAGCCCGTAGAACTGGACTTG-3′, TRBV19 probe, 5′-(6-FAM)-CCCCGCAACCACTTCCGCTG-(TAMRA)-3′; DEFA1 forward, 5′-CAGCCCCGGAGCAGATT-3′, DEFA1 reverse, 5′-TTTCGTCCCATGCAAGGG-3′, DEFA1 probe, 5′-(6-FAM)-CAGCGGACATCCCAGAAGTGGTTGT-(TAMRA)-3′; MYL4 forward, 5′-GGGCCTGCGTGTCTTTGA-3′, MYL4 reverse, 5′-CGTGCCGAAGCTCAGCA-3′ MYL4 probe, 5′-(6FAM)-AAGGAGAGCAATGGCACGGTCATGG-(TAMRA)-3′ (Applied Biosystems Inc.).

Calibration curves for DEFA1, TRBV19, and MYL4 were prepared with extracted total RNA from umbilical cord blood. The stock umbilical RNA was amplified with the WT–Ovation RNA Amplification System (NuGEN Technologies Inc.) and then serially diluted 10-fold to generate a curve. The calibration curve for GAPDH was prepared from commercially available Total RNA (Applied Biosystems Inc.).

The thermal cycle profile for all transcripts was as follows: the reaction was initiated at 48°C for 30 minutes for the uracil N-glycosylase to act, followed by reverse transcription at 60°C for 30 minutes. Following a 5-minute denaturing cycle at 95°C, 40 cycles of PCR were performed with 20 seconds of denaturing at 94°C, then 1 minute at 60°C for annealing and extension.

SNP analysis.

SNP analysis was performed both retrospectively on stored RNA samples and prospectively from genomic DNA and total RNA in whole blood collected from women and infants specifically for SNP identification in both cases. cDNA was synthesized from total RNA using the WT–Ovation RNA Amplification System (NuGEN Technologies Inc.). SNPs were chosen if their sequence was contained within a genomic DNA coding region and was found within the coding region identified on the HGU133a Affymetrix gene expression microarray. Additionally, each SNP had to demonstrate a high polymorphism rate (>10%) across multiple populations and be included in a gene transcript that was identified in our antepartum subjects no less than 90% of the time. Identification of SNPs was performed with the ABI 7900HT genotyping system based on TaqMan SNP genotyping technology (Applied Biosystems Inc.). Genomic DNA, when available, and cDNA samples were genotyped for each SNP assay using Applied Biosystems TaqMan SNP genotyping system (25).

Selection of candidate fetal genes.

Microarray data analysis was performed in R 2.3.0 using the Affy and Multtest packages in Bioconductor 1.8 (http://www.bioconductor.org/) (26). All of the arrays were normalized as a set using the quantile normalization method. Two sets of paired Student’s t tests were performed on the (base 2) log-transformed data from the whole blood samples, 1 comparing the antepartum and postpartum women, and 1 comparing the umbilical cord blood and the postpartum mothers. In the case of the twin pregnancy, each twin was compared to their mother as if there were 2 independent maternal-fetal pairs. The P values of these tests were adjusted for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate approach (27). Candidate fetal biomarkers were selected if they differed significantly (adjusted P values of less than 0.05) in both comparisons (antepartum vs. postpartum and umbilical vs. postpartum) and if the expression levels were lower in the postpartum samples in both cases (corresponding to having paired t scores less than 0 in each case). There were 157 transcripts that met these criteria.

Publicly available databases (OMIM, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=OMIM; PubMed, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez; and NetAffx, http://www.affymetrix.com/analysis/index.affx) describing the functional role and expression pattern of all statistically significant gene transcripts (Supplemental Table 2) were then manually reviewed to determine whether each gene potentially played a role in fetal development and well being.

Further information regarding the developmental profiles of the 157 transcripts was obtained from the publicly available database UniGene (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=unigene). Any transcript that had either been exclusively identified in the embryo or highly associated with embryos, fetuses, or neonates was identified as a candidate fetal gene transcript (qualifier). From the combined review of the annotation sources above and expression patterns in UniGene, a list of 71 candidate fetal markers was selected.

To determine if the gene transcripts that met statistical significance were consistent across maternal-fetal pairs, normalized log-transformed data were further analyzed (Supplemental Table 5). For each transcript, antepartum, umbilical, and postpartum values were examined across each maternal-fetal pair. Transcripts were considered positive if both the antepartum and umbilical values were greater than the postpartum sample. In rare instances, if either the antepartum or umbilical value was higher than the postpartum sample, but the other value was equal to the postpartum sample, this too was considered positive. The twin gestation was considered as 2 independent maternal-fetal pairs. Expression count values can be found in Tables 2–6 and Supplemental Table 1.

Pathway analysis.

The 157 transcripts were also analyzed for potential involvement in biological pathways. Using DAVID 2007 software (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/), the probability that each transcript would be found within a pathway compared with chance alone was calculated. These calculations were also done using pathways from Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes, BioCarta, and Biological Biochemical Image Database. The results are shown in Table 7.

Analysis of placental genes in the plasma samples.

Plasma microarray data were analyzed similarly to whole blood data as described above. A subset of 50 transcripts expressed by full-term placentas (7) was then selectively analyzed to determine if different expression profiles existed between whole blood and plasma obtained at the same time point. Comparisons between the whole blood and plasma array data were performed using paired Student’s t tests, adjusted as described above. χ2 tests were used to ensure that the fraction of genes that were higher in plasma in the placental gene set was not simply an array normalization artifact.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The support and assistance of Yue Shao, Jim Foster, Victor Wong, Mamta Mohan, Xian Adiconis, and Helen Stroh are gratefully acknowledged. This work was funded by NIH grants R01 HD42053 to D.W. Bianchi and 5T15 LM007092 and R01 HG003354 to M. Ramoni.

Footnotes

Nonstandard abbreviations used: cRNA, complementary RNA; DEFA1, defensin α1; MYL4, myosin light polypeptide 4, alkali, atrial, embryonic; TRBV19, T cell receptor β variable 19.

Conflict of interest: D.W. Bianchi’s laboratory receives sponsored research support, and D.W. Bianchi personally has stock options and receives compensation for consultation, from Living Microsystems.

Citation for this article: J. Clin. Invest. 117:3007–3019 (2007). doi:10.1172/JCI29959

References

- 1.Poon L.L.M., Leung T.N., Lau R.K., Lo Y.M.D. Presence of fetal RNA in maternal plasma. Clin. Chem. 2000;46:1832–1834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lo Y.M.D., et al. Quantitative analysis of fetal DNA in maternal plasma and serum: implications for noninvasive prenatal diagnosis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1998;62:768–775. doi: 10.1086/301800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costa J.M., et al. Fetal expressed gene analysis in maternal blood: A new tool for noninvasive study of the fetus. . Clin. Chem. 2003;49:981–983. doi: 10.1373/49.6.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qinyu G., Quanjun L., Yunfei B., Wen T., Lu Z. A semi-quantitative microarray method to detect fetal RNAs in maternal plasma. Prenat. Diagn. 2005;25:912–918. doi: 10.1002/pd.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ng E.K.O., et al. mRNA of placental origin is readily detectable in maternal plasma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. . 2003;100:4748–4753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0637450100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wataganara T., et al. Circulating cell-free fetal nucleic acid analysis may be a novel marker of fetomaternal hemorrhage after elective first-trimester termination of pregnancy. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2004;1022:129–134. doi: 10.1196/annals.1318.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsui N.B.Y., et al. Systematic micro-array based identification of placental mRNA in maternal plasma: towards non-invasive prenatal gene expression profiling. J. Med. Genet. 2004;41:461–467. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.016881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ng E.K.O., et al. The concentration of circulating corticotrophin-releasing hormone mRNA in maternal plasma is increased in preeclampsia. Clin. Chem. 2003;49:727–731. doi: 10.1373/49.5.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rainen L., et al. Stabilization of mRNA expression in whole blood samples. Clin. Chem. 2002;48:1883–1890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiu R.W.K., et al. Time profile of appearance and disappearance of circulating placenta-derived mRNA in maternal plasma. Clin. Chem. 2006;52:313–316. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.059691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsui N.B., Ng E.K., Lo Y.M. Stability of endogenous and added RNA in blood specimens, serum, and plasma. Clin. Chem. 2002;48:1647–1653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dennis G., Jr., et al. DAVID: Database for annotation, visualization, and integrated discovery. Genome Biol. . 2003;4:P3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wainwright M.S., et al. Increased susceptibility of S100B transgenic mice to perinatal hypoxia-ischemia. Ann. Neurol. 2004;56:61–67. doi: 10.1002/ana.20142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelemen K., Paldi A., Tinneberg H., Torok A., Szekeres-Bartho J. Early recognition of pregnancy by the maternal immune system. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 1998;39:351–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1998.tb00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wood G.W. Is restricted antigen presentation the explanation for fetal allograft survival? Immunol. Today. 1994;15:15–18. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bianchi D.W., Flint A.F., Pizzimenti M.F., Knoll J.H., Latt S.A. Isolation of fetal DNA from nucleated erythrocytes in maternal blood. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1990;87:3279–3283. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.9.3279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bianchi D.W., Zickwolf G.K., Weil G.J., Sylvester S., DeMaria M.A. Male fetal progenitor cells persist in maternal blood for as long as 27 years postpartum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1996;93:705–708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.2.705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.

- 19.Bukowski R., Hankins G.D.V., Saade G.R., Anderson G.D., Thornton S. Labor-associated gene expression in the human uterine fundus, lower segment, and cervix. . PLoS. Med. 2006;3:918–930. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shi L., et al. The MicroArray Quality Control (MAQC) project shows inter- and intraplatform reproducibility of gene expression measurements. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006;24:1151–1161. doi: 10.1038/nbt1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maron J.L., Bianchi D.W. Prenatal diagnosis using cell-free nucleic acids in maternal body fluids: a decade of progress. Am. J. Med. Genet. . 2007;145:5–17. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ng E.K.O., et al. Presence of filterable and nonfilterable mRNA in the plasma of cancer patients and healthy individuals. Clin. Chem. 2002;48:1212–1217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Gelder R.N., et al. Amplified RNA synthesized from limited quantities of heterogeneous cDNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1990;87:1663–1667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.5.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Livak K.J. Allelic discrimination using fluorogenic probes and the 5’ nuclease assay. Genet. Anal. 1999;14:143–149. doi: 10.1016/s1050-3862(98)00019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gentleman R.C., et al. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R80. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Draghici S., Khatri P., Martins R.P., Ostermeier G.C., Krawetz S.A. Global functional profiling of gene expression. Genomics. 2003;81:98–104. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(02)00021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benjamini Y., et al. 1995Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. (Ser. A). B 75290–300. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.