Abstract

Background and purpose:

S100A9 protein induces anti-nociception in rodents, in different experimental models of inflammatory pain. Herein, we investigated the effects of a fragment of the C-terminus of S100A9 (mS100A9p), on the hyperalgesia induced by serine proteases, through the activation of protease-activated receptor-2 (PAR2).

Experimental approach:

Mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia induced by PAR2 agonists (SLIGRL-NH2 and trypsin) was measured in rats submitted to the paw pressure or plantar tests, and Egr-1 expression was determined by immunohistochemistry in rat spinal cord dorsal horn. Calcium flux in human embryonic kidney cells (HEK), which naturally express PAR2, in Kirsten virus-transformed kidney cells, transfected (KNRK-PAR2) or not (KNRK) with PAR2, and in mouse dorsal root ganglia neurons (DRG) was measured by fluorimetric methods.

Key results:

mS100A9p inhibited mechanical hyperalgesia induced by trypsin, without modifying its enzymatic activity. Mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia induced by SLIGRL-NH2 were inhibited by mS100A9p. SLIGRL-NH2 enhanced Egr-1 expression, a marker of nociceptor activation, and this effect was inhibited by concomitant treatment with mS100A9p. mS100A9p inhibited calcium mobilization in DRG neurons in response to the PAR2 agonists trypsin and SLIGRL-NH2, but also in response to capsaicin and bradykinin, suggesting a direct effect of mS100A9 on sensory neurons. No effect on the calcium flux induced by trypsin or SLIGRL in HEK cells or KNRK-PAR2 cells was observed.

Conclusions and implications:

These data demonstrate that mS100A9p interferes with mechanisms involved in nociception and hyperalgesia and modulates, possibly directly on sensory neurons, the PAR2-induced nociceptive signal.

Keywords: S100A9, antinociception, hyperalgesia, inflammation, PAR2, Egr-1, DRG neurons, HEK cells, KNRK-PAR2 cells

Introduction

The S100A9 protein belongs to the family of S-100 proteins (Schäfer et al., 1995; Zimmer et al., 1995). It is composed of two calcium-binding motifs (Hessian et al., 1993), and forms a heterodimeric complex with the S100A8 protein, which is then called calprotectin (Steinbakk et al., 1990). S100A8 and S100A9 proteins are highly conserved, presenting 60–80% homology between human, rat and mouse (Edgeworth et al., 1991). Both proteins are expressed in circulating neutrophils and monocytes, where they represent 45 and 1% of the total cytosolic proteins of these cells, respectively (Hogg et al., 1989). Calprotectin is found in high concentrations in body fluids of patients with acute and chronic inflammatory diseases (Sorg, 1992; Brun et al., 1994; Golden et al., 1996). From these studies, the use of calprotectin as a diagnostic marker of inflammation in noninfectious inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease has been proposed (Foell et al., 2004; Striz and Trebichavsky, 2004).

As of its increased expression in inflammatory settings, studies have investigated the effects of calprotectin, S100A8 and S100A9 on different inflammatory parameters. Calprotectin induces a marked anti-inflammatory effect in a model of adjuvant-induced arthritis in rats (Brun et al., 1995), and modulates the growth and apoptotic activity of fibroblasts. These effects are physiologically controlled by metallic ions (Yui et al., 1997). S100A9 alone seems to play a prominent role in leukocyte trafficking, having chemotactic and proadhesive properties for neutrophils (Ryckman et al., 2003), and blockade of S100A9 suppressed neutrophil migration in response to lipopolysaccharide (Vandal et al., 2003). While these results suggest a proinflammatory role for S100A9, other studies have shown anti-inflammatory properties. For instance, S100A9, but not S100A8, deactivates activated peritoneal macrophages (Aguiar-Passeti et al., 1997). S100A9 released by neutrophils can reduce inflammatory pain in a model of neutrophilic peritonitis induced by glycogen or carrageenan in mice (Giorgi et al., 1998; Pagano et al., 2002). Further studies have determined that the C-terminal domain of the murine calcium-binding protein S100A9 (mS100A9p) reproduced several anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive properties of the full-length protein S100A9. mS100A9p inhibits spreading and phagocytic activity of adherent peritoneal cells (Pagano et al., 2005) and inhibits hyperalgesia induced by jararhagin, a metalloproteinase isolated from the Bothrops jararaca venom (Dale et al., 2004). However, to date, the antinociceptive effects of S100A9 have never been dissociated from its anti-inflammatory properties. It is not clear whether the antinociceptive properties of S100A9 are due to a general reduction of inflammation or whether S100A9 has analgesic properties.

Among the many mediators involved in inflammation, proteases have been identified as important actors, which can induce both edema and inflammatory cells recruitment and have a direct pronociceptive effect on sensory neurons (Vergnolle et al., 1999, 2001b, 2003; Kirkup et al., 2003). The effects of proteases on inflammation and pain parameters are mediated, at least in part, by the activation of protease-activated receptor-2 (PAR2). PAR2 is a G protein-coupled receptor that is activated by a unique mechanism whereby proteases such as trypsin or mast cell tryptase hydrolyze, at a specific cleavage site, the extra cellular N-terminus of the receptor. This cleavage exposes a new N-terminus that acts as a tethered ligand, which binds intramolecularly to initiate cellular signals (Nystedt et al., 1994; Bohm et al., 1996; Hollenberg et al., 1997; Vergnolle et al., 2003). Data obtained with the agonist peptide for PAR2, corresponding to the tethered ligand domain of the receptor (SLIGRL-NH2) have shown that PAR2 activation induces hyperalgesia independently of inflammation (Vergnolle et al., 2001a). Doses of PAR2 agonists that did not cause signs of inflammation (no edema, no increase in granulocyte recruitment or vasodilatation), were able to provoke profound and long-lasting thermal and mechanical hyperalgesia (Vergnolle et al., 2001a). We wanted to use this particular property of PAR2 activation to define potential direct analgesic properties for S100A9 that would be independent from its anti-inflammatory effect.

The present study aimed at investigating the effects of the C-terminal fragment of S100A9 against hyperalgesia and sensory neuron activation induced by PAR2 agonists.

Methods

Animals

Male Wistar rats weighing 170–180 g and male C57Bl6 mice were used throughout this study. Animals were maintained under controlled light cycle (12/12 h) and temperature (22±2°C) with free access to food and water. The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, and was approved by the Ethics Committee on Animal Experimentation.

Mechanical nociception

Nociceptive response to pressure was measured using an Ugo Basile paw pressure apparatus, as described by Randall and Selitto (1957). After measuring the baseline threshold (force at which rats before any treatment withdraw their paw), trypsin (50 μg), saline (0.9% NaCl), SLIGRL (10 μg) and/or mS100A9p (1, 4 or 8 μg) were injected (injection volume 100 μl) by the intraplantar (i.pl.) route in rats. Mechanical hyperalgesia was defined as a decrease of the threshold (force in g) required to induce paw withdrawal. Thresholds for paw withdrawal were measured in rats at different times after i.pl. injection.

Thermal nociception

Paw withdrawal latency to radiant heat stimulus was measured using an Ugo Basile Plantar test essentially as described by Hargreaves et al. (1988). Withdrawal latency of rats was measured before and after the i.pl. injection of SLIGRL (10 μg in 100 μl) and/or mS100A9p (0.1, 1 or 20 μg in 100 μl). Thermal hyperalgesia was defined as a significant decrease of the withdrawal latency, compared to basal measurement (time 0, before i.pl. injection).

Trypsin enzymatic activity assay

Enzymatic activity of trypsin was evaluated on chromogenic substrate BAPNA (Nα-benzoyl-DL-p-nitroanilide – Sigma). Trypsin at the dose of 50 μg or trypsin together with 50 μg of soybean trypsin inhibitor (SBTI) or trypsin with 1 or 4 μg of mS100A9p were added to 500 μl of 0.05 M of Tris-HCl buffer, pH 5.8 and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. After this incubation, the solutions were added to 1 ml of BAPNA (1 mM) and were incubated for 15 min at 37°C. The reactions were terminated with 30% acetic acid. The optical density of the incubation mixture was measured using a spectrophotometer, at 405 nm.

Immunohistochemistry

At 3 h after the i.pl. injection of SLIGRL (10 μg) or the concomitant injection of SLIGRL and mS100A9p (4 μg), rats were transcardially perfused with phosphate-buffered saline and 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB; pH 7.4). The spinal cord (L4 and L5) was removed, left in the same fixative for 5–8 h and then cryoprotected overnight in 30% sucrose. Frozen sections (30 μm) were immunostained for Egr-1 expression. The spinal cord sections were incubated free floating with a rabbit polyclonal antibody against the nuclear protein, which is the product of the early growth response-1 gene (egr-1) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), and diluted 1:200 in PB containing 0.3% Triton X-100 plus 5% of normal goat serum. Incubation with the primary antibody was conducted overnight at 24°C. After three washes (10 min each) in PB, the sections were incubated with biotinylated goat anti-rabbit sera (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA, USA) diluted 1:200 in PB for 2 h at 24°C. The sections were washed again in PB and incubated with the avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (ABC Elite; Vector Labs). After the reaction with 0.05% 3–3′-diaminobenzidine and a 0.01% solution of hydrogen peroxide in PB and intensification with 0.05% osmium tetroxide in water, the sections were mounted on gelatin- and chromoalumen-coated slides, dehydrated, cleared, and coverslipped. The material was then examined with a light microscope, and digital images were collected. A quantitative analysis of the immunolabeled material was performed with NIH Image. The number of Egr-1 immunoreactive neurons of the right dorsal horn (treated side) was compared with the left side, to obtain the difference between treated and nontreated sides. The results were compared and subjected to statistical analysis.

Calcium signal in PAR2-expressing cells

Human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells were maintained in 75 cm−2 T-flasks in minimum essential media (MEM – Gibco, Invitrogen Corporation, NY, USA), containing (v/v) 5% fetal bovine serum, 1% horse serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution (PSS) – Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA). Kirsten virus-transformed kidney cells stably expressing PAR2 cells (KNRK-PAR2) were used as previously described (Vergnolle et al., 1998), and maintained in 75 cm−2 T-flasks Dubelco's modified eagle medium (DMEM – Gibco), containing 5% v/v fetal calf serum, 1% geneticin (Gibco) and 1% PSS.

Cells were harvested at confluence to be used for trypsin or SLIGRL-induced calcium signals in suspension as previously described (Vergnolle et al., 1998). Cells were rinsed and disaggregated using isotonic calcium-free phosphate buffered saline (for HEK cells) or cell dissociation buffer (for KNRK-PAR2 cells – Gibco) and, after centrifugation, were resuspended in 1 ml of DMEM in the presence of the calcium indicator, Fluo-3 (Molecular Probes Inc., Eugene, OR, USA) at a final concentration of 25 μg ml−1 (22 μM). Cells were allowed to take up Fluo-3 for 25 min at room temperature, in the presence of 0.25 mM sulfinpyrazone, after which time the cells were rinsed twice by centrifugation and resuspended in buffer (in mM: NaCl, 150; KCl, 3; CaCl, 1.5; HEPES, 20; glucose, 10; sulfinpyrazone, 0.25) to remove excess dye. Cell concentrations of approximately 6 × 106 ml−1 was used for fluorescence studies. Fluorescence measurements, reflecting elevations of intracellular calcium, were conducted at 24°C, using a Perkin-Elmer fluorescence spectrophotometer, with an excitation wavelength of 480 nm and emission wavelength recorded at 530 nm. Cells were maintained in suspension in a stirred (round magnetic flea-bar) plastic cuvette (total volume 2 ml) maintained at 24°C, and peptide (SLIGRL 50 μM 2 ml−1) or trypsin (1 U 2 ml−1) stock solutions were added directly to the suspension.

Dorsal root ganglia neuron cultures and calcium imaging

Dorsal root ganglia (DRG) neurons from thoracic and lumbar spinal cord of mice were minced in cold Hank's balanced salt solution (HBSS – Sigma) and incubated for 90 min at 37°C in DMEM (low glucose – Sigma) containing (in mg ml−1): 0.5 trypsin, 1.0 collagenase type I and 0.1 DNase type A (Sigma) (Steinhoff et al., 2000). SBTI (Sigma) was added to neutralize trypsin. Neurons were centrifuged, pellets were suspended in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 10% horse serum, 1% PSS, glutamine (2 mM ml−1) and 2.5 μg ml−1 DNAse type IV and plated on glass coverslips Petri dishes (35 mm diameter; MatTek Corporation, Ashland, MA, USA) coated with Matrigel (BD Biosciences, Belford, MA, USA). Cells were cultured for a minimum of 72 h. The Petri dishes were then washed twice with a Hanks buffered salt solution, pH 7.4 and incubated for 60 min at 37°C with Hanks buffered salt solution supplemented with 0.1% bovine serum albumin in the same solution to which 3–5 μM of Fluo-3-AM was added. After the incubation period, the Petri dishes were washed twice again with the assay buffer (the same as described above) of which 2 ml were left in each Petri dish.

Cells were observed using a wide-field fluorescence Olympus IX-70 microscope and an LCPlan FL × 40 objective. The time course of changes was studied in a series of 30 pictures taken over 90 s; the five initial pictures were used to determine the baseline. Before the fifth picture, neurons were treated by an acute administration of SLIGRL (100 μM), trypsin (2.5 U ml−1), capsaicin (100 nM), bradykinin (10 nM) and/or mS100A9p (0.5, 5, 50 or 100 μM 2 ml−1). The experiment was repeated three times per group. Fluorescence measurements reflecting elevations of intracellular calcium were conducted at 460–490 nm excitation and 515 nm emission in individual cells using the acquisition program OpenLab software.

Substance P secretion

DRG neurons isolated from mice were rinsed in HBSS, and incubated in HBSS containing 1% Papain (Worthington, Cedarlane, Hornby, Ontario, Canada) for 10 min at 37°C. After a wash with filtered Leibovitz's L-15 Medium solution (glutamine (200 mM), glucose 20%, FBS 10%), DRG neurons were incubated in HBSS containing collagenase (1 mg ml−1) and dispase (4 mg ml−1) at 37°C for 10 min. After titration, cells were plated in Poly-L-ornithine-laminine (Sigma) glass-bottom Petri dishes (35 mm diameter; MatTek Corporation, Ashland, MA, USA) and recovered with the complete culture media MEM, 2.5% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, glutamine (200 mM), 1% dextrose and cytosine-β-D-arabino-furanoside hydrochloride, 5-fluoro-2-deoxi-uridine, uridine 10 μM each). Cells were incubated at 37°C for 5-min with HBSS alone (200 μl) or HBSS containing LRGILS 100 μM, SLIGRL 100 μM, mS100A9 100 μM or SLIGRL 100 μM plus mS100A9 100 μM. Cell supernatants were assayed for substance P (SP) using an enzymatic immunoassay kit (Assay Design, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) following the manufacturer's recommendations.

Presentation of data and analysis

All data are presented as the mean±s.e.m. Statistical analysis of data were generated using GraphPAd Prism, version 4.02 (Graph Pad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Statistical analysis between two samples was performed using Student's t-test. Statistical comparison of more than two groups was performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey's multiple comparisons post-test. In all cases, values of P<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Chemicals

The peptide identical to the C-terminus of murine S100A9 protein – H-E-K-L-H-E-N-N-P-R-G-H-G-H-S-H-G-K-G-NH2 (mS100A9p) – was synthesized based on the sequence published by Raftery et al. (1996). This peptide was synthesized in solid phase by fluorenil-metoxicarbonil (FMOC) technique. Characterization and purification were performed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), and its mass evaluated by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI-TOF) spectrometry. The peptide was diluted in saline at a final concentration of 1 mg ml−1.

PAR agonists

The peptide corresponding to the tethered ligand domain of PAR2 (S-L-I-G-R-L-NH2) and the control peptide (L-R-G-I-L-S-NH2) were purchased from EZbiolab Inc. (Westfield, IN, USA). Trypsin from porcine pancreas (10 200 U mg−1), trypsin inhibitor (SBTI), capsaicin and bradykinin were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, USA). Trypsin, SLIGRL-NH2, capsaicin and bradykinin were diluted in saline (0.9% NaCl).

Results

Effect of mS100A9p on trypsin-induced hyperalgesia

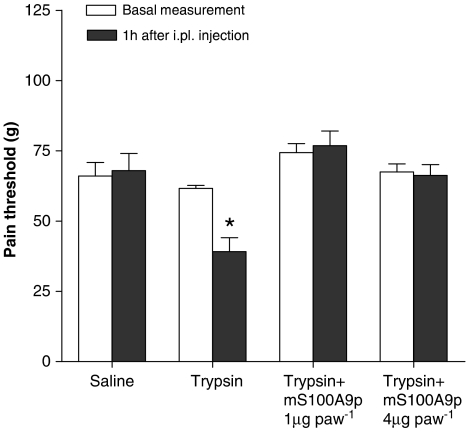

Rats received an i.pl. injection of trypsin at a dose of 50 μg, concomitantly with 1 or 4 μg of mS100A9p. Nociceptive threshold (in grams) in response to mechanical stimulus was measured before and after i.pl. injections. i.pl. injection of trypsin caused a decreased nociceptive threshold characteristic of hyperalgesia, and coinjection with mS100A9p inhibited trypsin-induced hyperalgesia (see Figure 1). Both doses of mS100A9p tested (1 and 4 μg) were effective at reducing trypsin-induced hyperalgesia (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Effects of mS100A9p on mechanical hyperalgesia induced by trypsin in rats. Trypsin (50 μg) was incubated for 30 min at 37°C with 1 or 4 μg of mS100A9p and the combination was then injected into the rat paw. Pain threshold in response to mechanical stimulation was measured in rats before (basal measurement) and 1 h after treatment using the paw pressure test. Rats injected with saline or trypsin alone were submitted to the same protocol. Data represent mean±s.e.m. of 6–8 animals per group. (*) Significantly different from basal measurements (P<0.05, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison post-test).

We further investigated whether or not the inhibitory effect of mS100A9p on trypsin-induced hyperalgesia could be caused by inhibition of trypsin proteolytic activity. The effect of mS100A9p on trypsin enzymatic activity was evaluated by following the hydrolysis of the chromogenic substrate BAPNA at 405 nm. Enzymatic activity of trypsin incubated in the presence of mS100A9p (1 or 4 μg) for 30 min was not reduced compared to the activity of trypsin used alone (see Table 1). In contrast, incubation of trypsin with SBTI (50 μg) completely inhibited trypsin activity (Table 1). Taken together, these results suggest that mS100A9p does not reduce trypsin-induced hyperalgesia by inhibiting trypsin enzymatic activity.

Table 1.

Effect of mS100A9p on the enzymatic activity of trypsin

| Experimental groups | Absorbance at 405 nm |

|---|---|

| Control group (Tris HCl buffer) | 0 |

| Trypsin 50 μg | 0.833 (±0.094) |

| Trypsin 50 μg+mS100A9p 1 μg | 0.550 (±0.116) |

| Trypsin 50 μg+mS100A9p 4 μg | 0.646 (±0.074) |

| Trypsin 50 μg+SBTI 50 μg | 0 |

| SBTI 50 μg | 0 |

| mS100A9p 4 μg | 0 |

The catalytic activity of trypsin was measured with the chromogenic substrate, BAPNA; incubation conditions are described in the Materials and methods. Preincubation of trypsin with mS100A9p (either 1or 4 μg) did not significantly affect the increase of absorbance at 405 nm, demonstrating no change in the catalytic activity of trypsin.

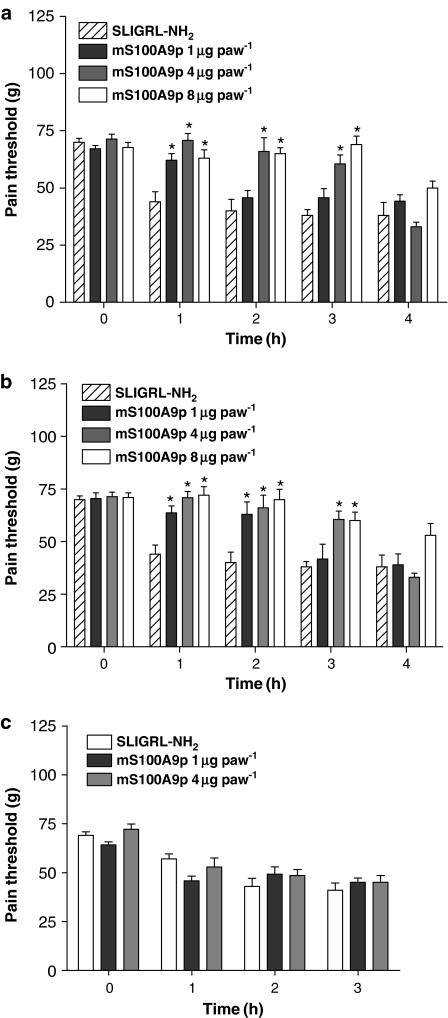

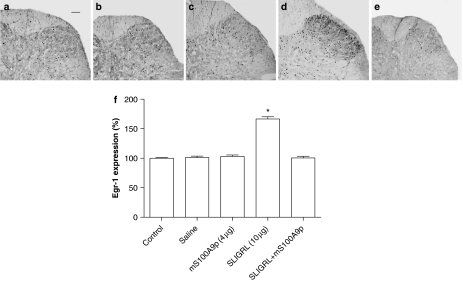

Effect of mS100A9p on PAR2-activating peptide-induced hyperalgesia

Because trypsin causes inflammation and pain by acting on PAR2 (Vergnolle et al., 2001a, Nguyen et al., 2003), we tested the effects of mS100A9p on selective PAR2 agonist-induced hyperalgesia. Rats received an i.pl. injection of the selective PAR2 agonist SLIGRL-NH2 at a dose of 10 μg, concomitantly with 1, 4 or 8 μg of mS100A9p. Nociceptive threshold (in grams) and withdrawal latency (in seconds) in response to mechanical and thermal stimulus, respectively, were measured before and after i.pl. injections. Administration of SLIGRL-NH2 caused a significant decrease of the nociceptive threshold (Figure 2) and withdrawal latency (Figure 3), characteristic of mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia, respectively. Concomitant administration of mS100A9p inhibited SLIGRL-induced mechanical hyperalgesia in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2a), with the lowest dose (1 μg) inhibiting hyperalgesia only at the first hour and by 45%, but the two higher doses (4 and 8 μg) reduced hyperalgesia from 1 to 3 h, and by 59 and 81%, respectively, at 3-h. Pretreatment (30 min before) with mS100A9p also significantly reduced SLIGRL-induced mechanical hyperalgesia (Figure 2b). Here again, the effect of mS100A9p was dose-dependent, as the dose of 1 μg of mS100A9p inhibited hyperalgesia by 45 and 48% at the first and second hours of evaluation, the dose of 4 μg of mS100A9p, inhibited hyperalgesia by 67% at the first hour, 97% at the second hour and 65% at the third hour, and the dose of 8 μg mS100A9p inhibited SLIGRL-induced hyperalgesia by 60% at the first hour, 100% at the second hour and by 50% at the third hour of evaluation. In contrast, post-treatment with mS100A9p (1 h after SLIGRL) did not modify SLIGRL-induced mechanical hyperalgesia at the two doses tested (1 and 4 μg) (Figure 2c).

Figure 2.

Effects of time of treatment with mS100A9p on mechanical nociception in rats induced by SLIGRL-NH2. The mS100A9p was given in doses of 1, 4 or 8 μg concomitantly (a), 30 min before (b) or 1 h after (c) i.pl. injection of 10 μg of SLIGRL-NH2. Animals were evaluated before (time 0), 1, 2, 3 and 4 h after treatment. Rats injected only with SLIGRL-NH2 received the same total volume as the other groups. Data represent mean±s.e.m. of 6–8 animals per group. (*) Significantly different from SLIGRL-NH2 alone at the same time-point (P<0.05, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison post-test).

Figure 3.

Effects of time of treatment with mS100A9p on thermal nociception in rats, induced by SLIGRL-NH2. The mS100A9p was given in doses of 0.1, 1 or 20 μg concomitantly (a), 30-min before (b) or 1-h after (c) i.pl. injection of 10 μg of SLIGRL-NH2. Animals were evaluated before (time 0), 1, 2 and 3 h after SLIGRL-NH2 administration. Rats injected only with SLIGRL-NH2 received the same total volume as the other groups. Data represent mean±s.e.m. of eight animals per group. (*) Significantly different from SLIGRL-NH2 alone at the same time-point (P<0.05), (**) significantly different from SLIGRL-NH2 alone at the same time-point (P<0.001), one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison post-test).

Similarly to mechanical stimuli, SLIGRL-induced thermal hyperalgesia was significantly reduced by concomitant i.pl. administration of mS100A9p (Figure 3a). The three doses tested (0.1, 1 and 20 μg) of mS100A9p inhibited SLIGRL-induced thermal hyperalgesia for the first 2-h, with the percentage inhibition ranging from 15 to 100%. Pretreatment with mS100A9p 30-min before i.pl. SLIGRL also caused inhibition of thermal hyperalgesia, but only for the two highest doses and only for the first hour (Figure 3b). As observed for mechanical hyperalgesia, post-treatment with mS100A9p, even at the two highest doses (1 and 20 μg; Figure 3c) did not significantly reduce SLIGRL-induced hyperalgesia.

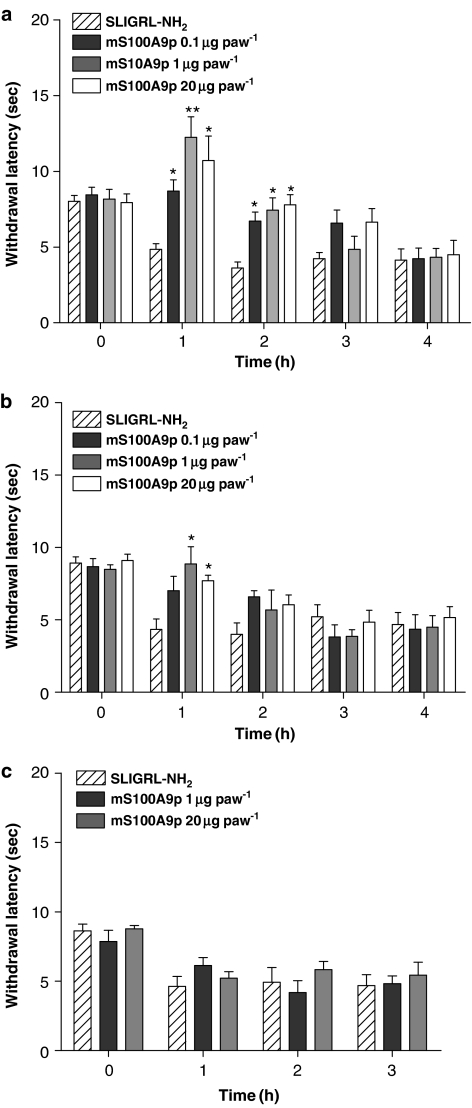

Activation of spinal nociceptors

Previous reports showed that i.pl. injection of SLIGRL enhanced c-fos expression in the superficial laminae of the dorsal horn of the spinal cord of rats (Vergnolle et al., 2001b). Here, we evaluated the effects of i.pl. administration of SLIGRL on expression of Egr-1, a marker of nociceptor activation similar to the Fos protein, in the presence or absence of mS100A9p. i.pl. injection of 10 μg of SLIGRL increased Egr-1 expression (56%) at the superficial laminae of the spinal dorsal horn, 3 h after the injection (Figure 4). Concomitant treatment with 4 μg of mS100A9p significantly inhibited the number of Egr-1 immunolabeled nuclei in the superficial laminae of the dorsal horn, while mS100A9p alone had no effect on the number of immunolabeled nuclei in basal conditions (Figure 4; n=6).

Figure 4.

Effects of saline, mS100A9p, SLIGRL-NH2 or SLIGRL-NH2 plus mS100A9p on dorsal horn expression of Egr-1. (a–e) Photomicrographs of immunostained sections of spinal cord dorsal horn from (a) naïve (control) animals, or from rats after i.pl. injection of: (b) saline; (c) 4 μg mS100A9p; (d) 10 μg SLIGRL-NH2; (e) concomitant treatment with SLIGRL-NH2 and mS100A9p. (f) quantitative changes in Egr-1 immunoreactivity in dorsal horn (L4 and L5) of rats. The spinal cords were collected 3 h after the treatments. Scale bar=50 μm. Data represent mean±s.e.m. of six animals per group. (*) Significantly different from all other groups (P<0.05, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison post-test).

Effects of mS100A9p on calcium mobilization in sensory neurons

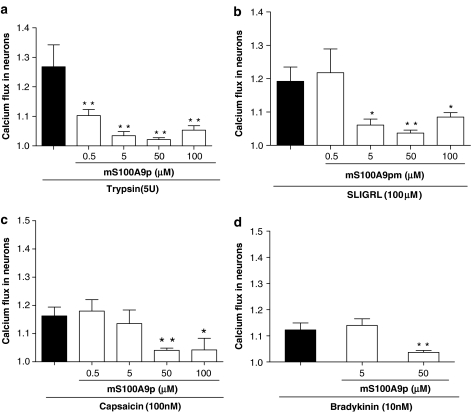

PAR2 is expressed and causes calcium influx in sensory neurons from DRG cultures (Steinhoff et al., 2000). We first wanted to investigate whether or not mS100A9p could interfere with PAR2 signaling in DRG neurons. Neurons were stimulated with two PAR2 agonists: trypsin (2.5 U ml−1, Figure 5a) or SLIGRL (100 μM, Figure 5b), concomitantly with mS100A9p at the concentrations of 0.5, 5, 50 or 100 μM. All the doses of mS100A9p tested, significantly inhibited the magnitude of calcium flux in DRG neurons in response to trypsin (2.5 U ml−1), and this effect was dose-dependent (Figure 5a). mS100A9p also inhibited the SLIGRL-induced calcium influx at the concentrations of 5 μM (11%), 50 μM (13%) and 100 μM (9%; Figure 5b). Next, we wanted to investigate whether mS100A9p was able to interfere with the signaling of other pronociceptive substances on sensory neurons. Therefore, isolated DRG neurons were stimulated by capsaicin (Figure 5c) or by bradykinin (Figure 5d), and the effects of different concentrations of mS100A9p on calcium mobilization were recorded. Capsaicin-induced calcium mobilization in DRG neurons was inhibited by 50 and 100 μM of mS100A9p (15 and 14%, respectively), but not by 0.5 or 5 μM (Figure 5c). Finally, 50 μM but not 5 μM of mS100A9p inhibited bradykinin-induced calcium mobilization in sensory neurons (10% inhibition; Figure 5d).

Figure 5.

Effect of mS100A9p on calcium flux in DRG neurons. Neurons were exposed to SLIGRL (100 μM; (a)), trypsin (5 U ml−1; (b)), capsaicin (100 nM; (c)) or bradykinin (10 nM; (d)) and concomitantly to mS100A9p (0.5 5, 50 or 100 μM). Neurons exposed only to SLIGRL, trypsin, capsaicin or bradykinin were considered as control groups. Calcium flux was measured by fluorescence (460–490 nm excitation and 515 nm emission) in individual cells using a Wide-Field Fluorescence Microscope. Kinetic studies of 30 pictures in 90 s were performed. Data represent mean±s.e.m. of 15–20 neurons per group. (*) Significantly different from control groups (P<0.05), (**) significantly different from control groups (P<0.001, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison post-test).

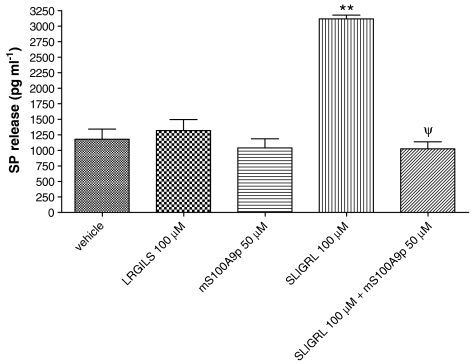

Effects of mS100A9p on PAR2-induced SP release by sensory neurons

PAR2 activation on sensory neurons causes SP release (Steinhoff et al., 2000). We wanted to investigate whether or not mS100A9p was able to also inhibit PAR2-induced SP release. As previously described, incubation of sensory neurons in the presence of the PAR2 agonist SLIGRL-NH2 (100 μM) caused a significant increase in SP release compared to the effects of the control peptide inactive on PAR2 LRGILS-NH2 (Figure 6). mS100A9p (50 μM) was able to completely inhibit the effects of PAR2 agonist on SP release stimulated by the agonist peptide, while it had no effect on SP release from DRG neurons exposed to mS100A9p alone (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Effects of vehicle, LRGILS-NH2, SLIGRL-NH2, mS100A9p or SLIGRL-NH2 plus mS100A9p on SP release by cultured DRG neurons. Data represent mean±s.e.m. of 15–20 neurons per group. (**) Significantly different from vehicle pr LRGILS-NH2 (P<0.001), (ψ) significantly different from SLIGRL-NH2 alone (P<0.05, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison post-test).

mS100A9p effect on PAR2 activation is specific for sensory neurons

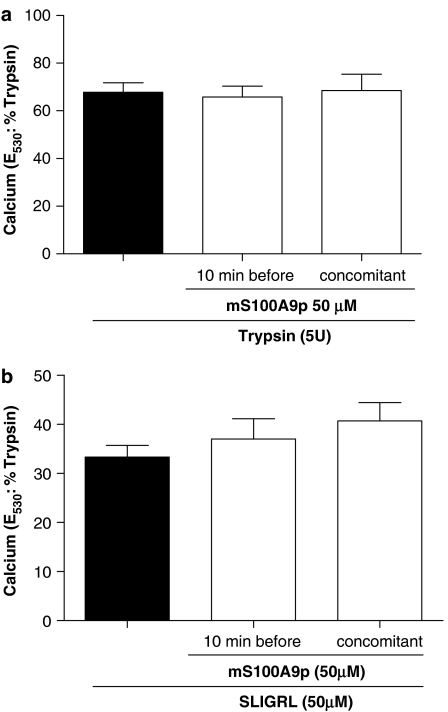

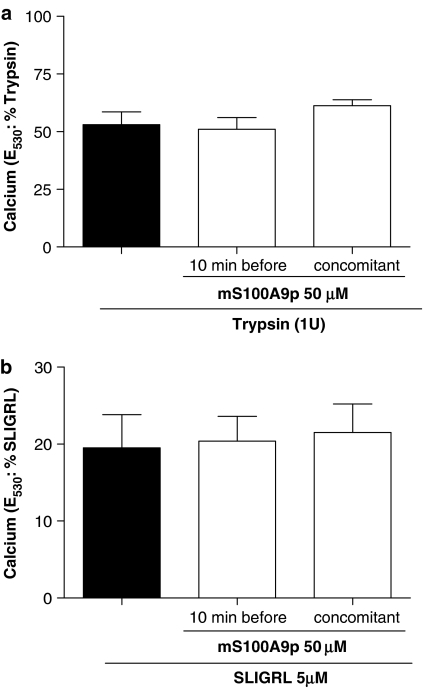

As mS100A9p was able to significantly inhibit PAR2-induced hyperalgesia and PAR2-induced calcium signal in sensory neurons, we wanted to investigate whether or not mS100A9p could act as a PAR2 antagonist. Therefore, we used HEK cells naturally expressing PAR2, and KNRK cells stably transfected with PAR2, or untransfected cells and evaluated the effects of mS100A9p on calcium flux. In HEK cells, the response to trypsin (5 U ml−1) was not modified by concomitant or pre-exposure of cells to 50 μM of mS100A9p (Figure 7a). Similarly, response of those cells to the selective PAR2 agonist SLIGRL-NH2 was not modified by mS100A9p (Figure 7b). KNRK nontransfected cells did not respond to trypsin or the selective PAR2 agonist SLIGRL-NH2 (data not shown). In contrast, KNRK PAR2-transfected cells showed calcium mobilization in response to trypsin (5 U ml−1) or SLIGRL-NH2 (5 μM), but the amplitude of those responses was not modified by concomitant, or pre-exposure to mS100A9p (Figure 8).

Figure 7.

Effect of mS100A9p on calcium signaling in HEK-293 cells. (a) Cells were activated by the exposure to 5 U of trypsin alone or by trypsin plus 50 μM of mS100A9p. Trypsin and mS100A9p were incubated either 10 min before cell exposure or at the same time (b). Cells were activated by the exposure to 50 μM of SLIGRL-NH2 alone or by SLIGRL-NH2 plus 50 μM of mS100A9p. SLIGRL-NH2 and mS100A9p were incubated either 10 min before cell exposure or at the same time. Cells were monitored for fluorescence and the response to mS100A9p treatment was compared to the response of cells exposed only to the agonists (trypsin or SLIGRL-NH2). The data are illustrative of four or more independently conducted experiments.

Figure 8.

Effect of mS100A9p on calcium signaling in KNRK-PAR2 cells. (a) Cells were activated by the exposure to 1 U of trypsin alone or by trypsin plus 50 μM of mS100A9p. Trypsin and mS100A9p were incubated either 10 min before cell exposure or at the same time (b). Cells were activated by the exposure to 50 μM of SLIGRL-NH2 alone or by SLIGRL-NH2 plus 50 μM of mS100A9p. SLIGRL-NH2 and mS100A9p were incubated either 10 min before cell exposure or at the same time. Cells were monitored for fluorescence and the response to mS100A9p treatment was compared to the response of cells exposed only to the agonists (trypsin or SLIGRL-NH2). The data are illustrative of four or more independently conducted experiments.

Discussion

Antinociceptive properties for S100A9 protein have been demonstrated in different models of inflammatory pain, where this protein inhibited hyperalgesia and nociception (Giorgi et al., 1998; Pagano et al., 2002). However, anti-inflammatory effects are also associated with the C-terminus of S100A9. Murine S100A9 C-terminal peptide (mS100A9p) inhibits spreading and phagocytic activity of adherent peritoneal cells (Pagano et al., 2005). Also, mS100A9p inhibits hyperalgesia and edema induced by jararhagin, a metalloproteinase, through inhibition of its enzymatic activity (Dale et al., 2004). Therefore, it was not clear whether the analgesic properties of mS100A9p were due to inhibition of different proinflammatory parameters, which would then lead to a reduction of inflammatory hyperalgesia, or whether mS100A9p could exert a direct inhibitory effect on inflammatory pain. As serine proteases, and the receptors they activate, the protease-activated receptors (PARs), have been shown to play a pivotal role in pain transmission, independently of their effects on inflammation (Hoogerwerf et al., 2001; Vergnolle et al., 2001a, 2003; Ossovskaya and Bunnett 2004), we wanted to investigate the effects of the C-terminal fragment of the S100A9 protein (mS100A9p) on the hyperalgesia induced by trypsin and by a selective PAR2 agonist.

We found that mS100A9p inhibited hyperalgesia induced by trypsin in rats, evaluated by the paw pressure test. This effect was not dependent on an inhibitory action of the peptide upon trypsin enzymatic activity, since mS100A9p did not inhibit trypsin catalytic activity. These results suggested that the effects of mS100A9p on trypsin-induced hyperalgesia were not due to inhibition of serine protease activity released at the inflammatory site. The antihyperalgesic effects of the peptide were also observed with hyperalgesia induced by the PAR2 agonist peptide SLIGRL-NH2. Previous studies have demonstrated, and we have confirmed in our study (data not shown), that at the dose of SLIGRL-NH2 we used (10 μg per rat paw), no inflammatory reaction was observed – no edema, no vasodilatation, no increase in prostaglandin release and no granulocyte infiltration (Vergnolle et al., 2001a). Therefore, the antinociceptive effects of mS100A9p do not seem to be related to its potential anti-inflammatory effects, but rather to the possibility that mS100A9p could act directly on the pathways that relay nociceptive messages.

mS100A9p not only significantly inhibited PAR2-induced hyperalgesia in rats submitted either to mechanical or to thermal nociceptive tests, but also decreased nociceptor activation at the spinal level. The expression of proto-oncogenes from the c-fos, c-jun and egr-1 family are extensively used as tools for the expression of enhanced activity of nociceptive neurons (Herdegen et al., 1991; Buritova et al., 1995). Our results demonstrated that the i.pl. administration of SLIGRL-NH2 induced a significant increase of Egr-1 expression, which is characteristic of nociceptor activation. This result is in accordance with previously published data showing that Fos protein expression was increased in the nuclei of neurons of the spinal dorsal horn, in response to i.pl. PAR2 agonist (Vergnolle et al., 2001a). Interestingly, we showed here that mS100A9p is able to interfere with the transmission of PAR2-induced pain message to the central nervous system, reducing nociceptor activation at a central level. Moreover, we showed that mS100A9p can act directly on sensory neuron activation, inhibiting PAR2-, bradykinin-, and capsaicin-induced calcium mobilization in DRG neurons. This result reveals sensory neurons as another important cellular target for the effects of S100A9 protein in the context of inflammation and also suggests an antinociceptive role for S100A9 independent of its effects on inflammation.

As proteases are largely released at sites of inflammation and as they have been demonstrated to be able to signal directly to sensory neurons through the activation of PAR2, causing sensitization and ultimately pain signals (Hoogerwerf et al., 2001; Vergnolle et al., 2001a; Kirkup et al., 2003; Reed et al., 2003), it was possible that mS100A9p acted as a PAR2 antagonist to reduce the transmission of pain signals. We tested this hypothesis by investigating the effects of mS100A9p in cells, other than sensory neurons, that express PAR2. We showed that mS100A9p, at a dose (50 μM) that showed maximal effect in DRG neurons against PAR2 agonists, was not able to modify the amplitude of the calcium response of HEK cells naturally expressing PAR2, or of PAR2-transfected KNRK cells to trypsin or SLIGRL-NH2. This result suggests that mS100A9p did not act as a direct antagonist on PAR2. One explanation could also be that signaling pathways involved in calcium mobilization are different in DRG neurons and HEK or KNRK-transfected cells. mS100A9p could antagonize signaling pathways and calcium mobilization downstream from PAR2 activation. The fact that calcium mobilization in DRG neurons induced by three different agonists, capsaicin, bradykinin and the PAR2 agonist, was inhibited by mS100A9p suggested that mS100A9p acted on a process common to these activators of sensory neurons. Importantly, our results showed a dose–response effect for the antinociceptive properties and inhibition of calcium mobilization of mS100A9p, against PAR2 agonists. As mS100A9p inhibits calcium mobilization in response to the activation of three different receptors: bradykinin B2 receptor, transient receptor potential vanillin -1 (TRPV1: activated by capsaicin in DRG neurons) or PAR2, one hypothesis could be that mS100A9p blocks a calcium channel present on sensory neurons and common to the signaling pathway of those three receptors. A more definitive understanding of the mechanism of action of S100A9 on inflammatory and nociceptive mediator biology represents the next challenge in this field.

We found that mS100A9p inhibits PAR2-induced SP release in cultured DRG neurons. Considering the pivotal role played by SP in the transmission of nociceptive message (Harrison and Geppetti, 2001), our results suggest that the analgesic properties of mS100A9p in vivo, could be due to such inhibition of SP release, thus preventing further activation of pain pathways.

In conclusion, our data has presented evidence that the C-terminal of the S100A9 protein exhibits antinociceptive properties against PAR2-induced pain. This effect of the S100A9 fragment is independent of anti-inflammatory properties of this peptide. Lastly, we present here evidence that mS100A9p can directly signal to sensory neurons, which are thus highlighted as important cellular targets of the effects of S100A9. Our data reinforce the potential prominent role that S100A9 could play in the control of inflammatory pain.

Acknowledgments

This study was part of the PhD thesis of Camila Squarzoni Dale, carried out at the Department of Pathology, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of São Paulo, Program of Experimental and Comparative Pathology. We thank Dr Morley Hollenberg, from the Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics of University of Calgary, for the use of the fluorescence spectrophotometer and Dr Pina Colarusso from the Department of Physiology & Biophysics for the use of the fluorescence microscope. We also thank Dr Luis Roberto de Carmargo Gonçalves from the Laboratory of Pathophysiology of Butantan Institute for the chromogenic substrate and Adilson da Silva from the Department of Physiology and Biophysics of the Institute of Biomedical Sciences for technical support. This work was supported by CAPES, FAPESP and the Canadian Institute for Health Research.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

one-way analysis of variance

- egr-1 gene

early growth response-1 gene

- DRG neurons

dorsal root ganglia neurons

- HEK cells

human embryonic kidney cells

- KNRK

Kirsten virus-transformed kidney

- KNRK-PAR2

Kirsten virus-transformed kidney PAR2 transfected cells

- NIF

neutrophil immobilizing factor

- PAR

protease-activated receptor

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Aguiar-Passeti T, Postol E, Sorg C, Mariano M. Epithelioid cells from foreign-body granuloma selectively express the calcium-binding protein MRP-14, a novel down-regulatory molecule of macrophage activation. J Leukoc Biol. 1997;62:852–858. doi: 10.1002/jlb.62.6.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohm SK, Kong W, Bromme D, Smeekens SP, Anderson DC, Connolly A, et al. Molecular cloning, expression and potential functions of the human proteinase-activated receptor-2. Biochem J. 1996;14:1009–1016. doi: 10.1042/bj3141009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buritova J, Honore P, Besson JM. Indomethacin reduces both Krox-24 expression in the rat lumbar spinal cord and inflammatory signs following intraplantar carrageenan. Brain Res. 1995;674:211–220. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00009-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brun JG, Haland G, Haga HJ, Fagerhol MK, Jonsson R. Effects of calprotectin in avridine-induced arthritis. APMIS. 1995;103:233–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1995.tb01100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brun JG, Jonsson R, Haga HJ. Measurement of plasma calprotectin as an indicator of arthritis and disease activity in patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:733–738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale CS, Goncalves LRC, Juliano L, Juliano MA, Moura-da-Silva AM, Giorgi R. The C-terminus of murine S100A9 inhibits hyperalgesia and edema induced by jararhagin. Peptides. 2004;25:81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgeworth J, Gorman M, Bennett R, Freemont P, Hogg N. Identification of p8, 14 as a highly abundant heterodimeric calcium binding protein complex of myeloid cells. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:7706–7713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foell D, Frosch M, Sorg C, Roth J. Phagocyte-specific calcium-binding S100 proteins as clinical laboratory markers of inflammation. Clin Chim Acta. 2004;344:37–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2004.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi R, Pagano RL, Dias MA, Aguiar-Passeti T, Sorg C, Mariano M. Antinociceptive effect of the calcium-binding protein MRP-14 and the role played by neutrophils on the control of inflammatory pain. J Leukoc Biol. 1998;64:214–220. doi: 10.1002/jlb.64.2.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden BE, Clohessy PA, Russell G, Fagerhol MK. Calprotectin as a marker of inflammation in cystic fibrosis. Arch Dis Child. 1996;74:136–139. doi: 10.1136/adc.74.2.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves K, Dubner R, Brown F, Flores C, Joris J. A new and sensitive method for measuring thermal nociception in cutaneous hyperalgesia. Pain. 1988;32:77–88. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison S, Geppetti P. Substance P. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2001;33:555–576. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(01)00031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hessian PA, Edgeworth J, Hogg N. MRP-8 and MRP-14, two abundant Ca (2+)-binding proteins of neutrophils and monocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 1993;53:197–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herdegen T, Kovary K, Leah J, Bravo R. Specific temporal and spatial distribution of JUN, FOS, and KROX-24 proteins in spinal neurons following noxious transsynaptic stimulation. J Comp Neurol. 1991;313:178–191. doi: 10.1002/cne.903130113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenberg MD, Saifeddine M, Al-Ani B, Kawabata A. Proteinase-activated receptors: structural requirements for activity, receptor cross-reactivity, and receptor selectivity of receptor-activating peptides. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1997;75:832–841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg N, Allen C, Edgeworth J. Monoclonal antibody 5.5 reacts with p8, 14, a myeloid molecule associated with some vascular endothelium. Eur J Immunol. 1989;9:1053–1061. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830190615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogerwerf WA, Zou L, Shenoy M, Sun D, Micci MA, Lee-Hellmich H, et al. The proteinase-activated receptor 2 is involved in nociception. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9036–9042. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-22-09036.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkup AJ, Jiang W, Bunnett NW, Grundy D. Stimulation of proteinase-activated receptor 2 excites jejunal afferent nerves in anaesthetised rats. J Physiol. 2003;552:589–601. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.049387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nystedt S, Emilsson K, Wahlestedt C, Sundelin J. Molecular cloning of a potential proteinase activated receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1994;91:9208–9212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.20.9208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen C, Coelho AM, Grady E, Compton SJ, Wallace JL, Hollenberg MD, et al. Colitis induced by proteinase-activated receptor-2 agonists is mediated by a neurogenic mechanism. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2003;81:920–927. doi: 10.1139/y03-080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ossovskaya VS, Bunnett NW. Protease-activated receptors: contribution to physiology and disease. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:579–621. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00028.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagano RL, Dias MA, Dale CS, Giorgi R. Neutrophils and the calcium-binding protein MRP-14 mediate carrageenan-induced antinociception in mice. Mediators Inflamm. 2002;11:203–210. doi: 10.1080/0962935029000050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagano RL, Sampaio SC, Juliano L, Juliano MA, Giorgi R. The C-terminus of murine S100A9 inhibits spreading and phagocytic activity of adherent peritoneal cells. Inflamm Res. 2005;54:204–210. doi: 10.1007/s00011-005-1344-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall LO, Selitto JJ. A method for measurement of analgesic activity on inflamed tissue. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1957;111:409–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raftery MJ, Harrison CA, Alewood P, Jones A, Geczy CL. Isolation of the murine S100 protein MRP14 (14 kDa migration-inhibitory-factor-related protein) from activated spleen cells: characterization of post-translational modifications and zinc binding. Biochem J. 1996;316:285–293. doi: 10.1042/bj3160285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed DE, Barajas-Lopez C, Cottrell G, Velazquez-Rocha S, Dery O, Grady EF, et al. Mast cell tryptase and proteinase-activated receptor 2 induce hyperexcitability of guinea-pig submucosal neurons. J Physiol. 2003;547:531–542. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.032011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryckman C, Vandal K, Rouleau P, Talbot M, Tessier PA. Proinflammatory activities of S100: proteins S100A8, S100A9, and S100A8/A9 induce neutrophil chemotaxis and adhesion. J Immunol. 2003;170:3233–3242. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.3233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer BW, Wicki R, Engelkamp D, Mattei MG, Heizmann CW. Isolation of a YAC clone covering a cluster of nine S100 genes on human chromosome 1q21: rationale for a new nomenclature of the S100 calcium-binding protein family. Genomics. 1995;25:638–643. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(95)80005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorg C. The calcium binding proteins MRP8 and MRP14 in acute and chronic inflammation. Behring Inst Mitt. 1992;91:126–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbakk M, Naess-Andresen CF, Lingaas E, Dale I, Brandtzaeg P, Fagerhol MK. Antimicrobial actions of calcium binding leucocyte L1 protein, calprotectin. Lancet. 1990;336:763–765. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)93237-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhoff M, Vergnolle N, Young SH, Tognetto M, Amadesi S, Ennes HS, et al. Agonists of proteinase-activated receptor 2 induce inflammation by a neurogenic mechanism. Nat Med. 2000;6:151–158. doi: 10.1038/72247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striz I, Trebichavsky I. Calprotectin –a pleiotropic molecule in acute and chronic inflammation. Physiol Res. 2004;53:245–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandal K, Rouleau P, Boivin A, Ryckman C, Talbot M, Tessier PA. Blockade of S100A8 and S100A9 suppresses neutrophil migration in response to lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol. 2003;171:2602–2609. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.5.2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergnolle N, Bunnett NW, Sharkey KA, Brussee V, Compton SJ, Grady EF, et al. Proteinase-activated receptor-2 and hyperalgesia: a novel pain pathway. Nat Med. 2001a;7:821–826. doi: 10.1038/89945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergnolle N, Ferazzini M, D'andrea MR, Buddenkotte J, Steinhoff M. Proteinase-activated receptors: novel signals for peripheral nerves. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:496–500. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00208-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergnolle N, Hollenberg MD, Sharkey KA, Wallace JL. Characterization of the inflammatory response to proteinase-activated receptor-2 (PAR2)-activating peptides in the rat paw. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;127:1083–1090. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergnolle N, Macnaughton WK, Al-Ani B, Saifeddine M, Wallace JL, Hollenberg MD. Proteinase-activated receptor 2 (PAR2)-activating peptides: identification of a receptor distinct from PAR2 that regulates intestinal transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95:7766–7771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergnolle N, Wallace JL, Bunnett NW, Hollenberg MD. Protease-activated receptors in inflammation, neuronal signaling and pain. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001b;22:146–152. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01634-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yui S, Mikami M, Tsurumaki K, Yamazaki M. Growth-inhibitory and apoptosis-inducing activities of calprotectin derived from inflammatory exudate cells on normal fibroblasts: regulation by metal ions. J Leukoc Biol. 1997;61:50–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer DB, Cornwall EH, Landar A, Song W. The S100 protein family: history, function, and expression. Brain Res Bull. 1995;37:417–429. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(95)00040-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]