Abstract

Background

Int-6 (integration site 6) was identified as an oncogene in a screen of tumorigenic mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) insertions. INT6 expression is altered in human cancers, but the precise role of disrupted INT6 in tumorigenesis remains unclear, and an animal model to study Int-6 physiological function has been lacking.

Principal Findings

Here, we create an in vivo model of Int6 function in zebrafish, and through genetic and chemical-genetic approaches implicate Int6 as a tissue-specific modulator of MEK-ERK signaling. We find that Int6 is required for normal expression of MEK1 protein in human cells, and for Erk signaling in zebrafish embryos. Loss of either Int6 or Mek signaling causes defects in craniofacial development, and Int6 and Erk-signaling have overlapping domains of tissue expression.

Significance

Our results provide new insight into the physiological role of vertebrate Int6, and have implications for the treatment of human tumors displaying altered INT6 expression.

Introduction

Embryonic development and tumour development often share underlying molecular mechanisms–a concept illustrated by the identification of genes disrupted by the mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) in mammary cancers [1]. An important example, the Int-1 gene which is a common integration site for MMTV in mammary tumours, encodes the homologue of the Drosophila wingless gene [2], [3] and was subsequently named Wnt1 (wingless/Int) in recognition of this conserved function. Wnt signaling is now known to be disrupted in many human tumor types, especially colon cancer [4]. Other Int genes, such as Int-2 and 4 (Fgf3, 4), and Int-3 (Notch4), encode mitogens and regulators of development that are also misactivated in many cancers [1], [5].

In the majority of cases, MMTV activates Int gene expression as a result of proviral integration upstream of the promoter region. Remarkably, all three MMTV insertions found in Int-6, which encodes a component of the eukaryotic translation initation factor 3 (eIF3), were found to lie within introns, and in the opposite transcriptional orientation to the Int-6 gene, creating a truncated Int-6 mRNA [1], [6]. Ectopic expression of equivalently truncated Int-6 can transform cell cultures [7], [8], and promote persistent mammary alveolar hyperplasia and tumorigenesis in transgenic mice [9].

Despite important evidence in favor of a role for INT6 in human tumourigenesis [10]–[12], the molecular basis for INT6 in cancer development remains unresolved. Highly conserved in eukaryotes, INT6 contains a PCI domain, found in proteins of the 19S regulatory lid of the proteasome, the COP9 signalosome (CSN), and the eIF3 translation initiation complex; all three complexes share overall structural similarity, and INT6 has been found associated with each [13]. When overexpressed in yeast, Int6 induces multi-drug resistance by activating an AP-1 transcription factor [14], [15], and in human cells, the range of INT6 function includes orderly progression through mitosis [16], regulation of the proteasome-dependent stability of MCM7 [17] and HIF2α [18], and nonsense mediated mRNA decay [19].

With no animal model for Int6 loss-of-function available, we reasoned that an understanding of INT6 during development would provide novel insight into INT6 function in normal vertebrate cells, thereby providing a new perspective on INT6 function in cancer formation. Here, using zebrafish and mammalian cells, we describe the first Int6 loss-of-function phenotype in an animal, and link Int6 with a signaling pathway, that like those effected by other Int genes, is critical for both development and cancer.

Results

Int6 is essential for zebrafish embryogenesis

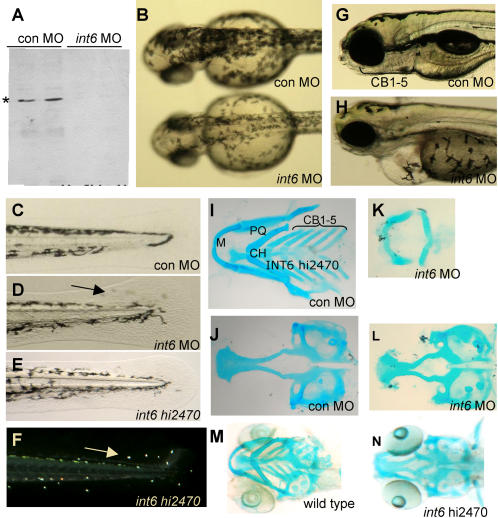

We chose to study the physiological role of zebrafish Int6 during development, using morpholino oligonucleotides (MOs) to reduce Int6 protein, as well as an int6hi2470 insertional mutant line (kindly provided by N. Hopkins, A. Amsterdam and S. Farrington. M.I.T.). Zebrafish Int6 is over 90% identical in its amino acid sequence to human INT6 (Ensembl ENSDARG00000002549) and using an Int6 antibody raised against the N-terminus of the human INT6 [20] we determined that the int6 MO resulted in loss of Int6 (Figure 1A). As INT6 has been implicated in G2/M-phase cell cycle control, we first performed whole-mount immunohistochemistry with the late G2/M phase marker, phospho-histone H3, and found only slightly reduced numbers of cells in late G2/M phase in the int6 morphant compared to the control (Figure S1). Importantly, we found that embryos injected with int6 MO had specific developmental defects (Figure 1B–N), most notably reduced melanisation 2 days post-fertilization (dpf: int-6 MO n = 51/53; con MO n = 0/35; int-6 5MM n = 3/31); misplaced pigment cells in the tail 3 dpf (int-6 MO n = 46/49; con MO n = 3/30); and abnormal jaw morphogenesis, with cartilage elements reduced or malformed at 4 and 5 dpf (int-6 MO n = 81/85 4 dpf, n = 76/83 5 dpf; con MO 1/67 4 dpf, n = 1/61 5 dpf). The craniofacial and pigment cell defects observed in the int-6 morphant and hi2470 mutant suggest that int-6 might contribute to development of neural crest-cell (NCC) derivatives. We used multiple markers of NCCs and their derivatives to assess when these phenotypes arise, and found Int6 did not appear to be required for the specification or organization of premigratory and migrating cartilage precursors (Figure S2). In contrast, alcian blue cartilage staining revealed a specific loss of the five ceratobranchial cartilage elements in the int6 morphants, whereas Meckel's, palatoquadrate, and hyoid cartilage were all present, albeit misshapen (5.5 dpf int6 MO n = 45/53; con MO n = 1/34; Figure 1I–L, Figure S3). Expression of int6 mRNA restored normal craniofacial elements to the int6 morphant (data not shown); and the int6hi2470 mutant had an almost identical craniofacial phenotype (Figure 1M, N) indicating a genuine requirement for Int6 in craniofacial development.

Figure 1. Int6 is essential for zebrafish embryonic development.

(A) Western blot analysis of Int6 (*) in zebrafish embryos injected with a control (con) MO or int6 MO. (B) int6 morphant melanocytes are less darkly pigmented. (C–F) Int6 is required for pigment cell placement in the tail, as int6 morphants and int6hi2470 mutants have misplaced pigment cells in the tail fin (D, arrow). Ambient light illuminates the iridophore ‘star-light’ pattern seen in the int6hi2470 embryos (F, arrow). (G–H) By 5 dpf, embryos injected with a con MO have clearly visible certobranical arches, while int6 morphants do not have visible certobranical arches, in addition to other abnormalities, including unconsumed yolk sac, heart and eye development. (I–N). Alcian blue staining of 5 dpf embryos shows loss of ceratobrancial arches 1 through 5. M, Meckel's; PQ, palatoquadrate; CH, ceratohyal; CB, ceratobrancial.

Loss of Int6 alters MEK protein and Erk signaling

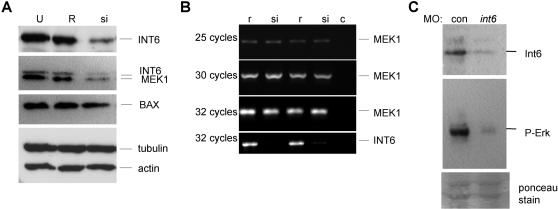

Biochemical evidence in fission yeast suggests that Int6 is part of a specialized eIF3 translation initiation complex that may target specific mRNAs for translation [21]. Given the involvement of INT6 in cell proliferation [16], western blots using a panel of antibodies against proteins involved in the cell cycle and associated signalling pathways were performed using lysates from control and INT6 siRNA transfected MDA-MB-231 cells. Of 16 proteins investigated in this way, only MEK1 levels were altered by INT6 siRNA transfection (Figure 2). As previously reported [20], we found INT6-siRNA cell lysates had reduced levels of INT6 protein compared with the untransfected and reverse INT6-siRNA sequence. We also found a dramatic reduction of MEK1 protein levels that correlated with loss of INT6, while BAX, tubulin and actin protein levels appeared unaffected in the INT6-siRNA transfected cells (Figure 2A). The loss of MEK1 was specifically at the protein level, as semi-quantitative-PCR showed normal levels of MEK1 mRNA in INT6-siRNA treated cells, as well as the expected reduced levels of the INT6 message in the INT6-siRNA transfected cells (Figure 2B). The possibility that INT6 may affect MAPK signaling through control of MEK protein levels prompted us to examine the phosphorylation state of Erk1/2, downstream targets of the Mek kinases, in int6 morphant zebrafish embryos. Compared with control MO embryos, int6 morphant embryo lysates had reduced phospho-Erk levels (Figure 2C). These data suggest a novel function for Int6 in the control of MAPK signaling in the developing embryo, possibly by direct control of MEK1 protein levels.

Figure 2. INT6 is required for MEK protein levels and Erk-signaling.

A. Osteosarcoma U2-OS cells untransfected (U), or transfected with siRNA targeted against the INT6 mRNA (si) or the reverse sequence (R), show reduced levels of INT6 and MEK1 protein specifically after transfection with INT6-siRNA, but no reduction in BAX, tubulin or actin protein levels. (B) Semi-quantitative-PCR shows MEK1 mRNA is unaffected in reverse sequence and INT6-siRNA treated cells, coupled with the expected reduced levels of the INT6 message in the INT6-siRNA transfected cells. c, PCR control without DNA. (C) Phospho-Erk levels are reduced in int6 morphants, while ponceau stain detects equal loading of protein on the gel.

Int6 and Mek pathways converge during development

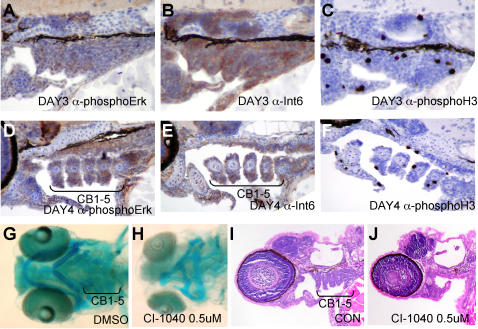

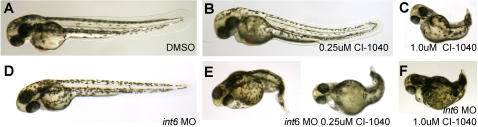

If Int6 controls Mek activity in the developing embryo, we theorized that specific developing tissues might have overlapping expression domains of Int6 protein and phospho-Erk activity. Indeed, immunohistochemistry with antibodies directed against Int6 and phospho-Erk revealed overlapping domains of expression in the developing craniofacial region in 3 and 4 dpf embryos (Figure 3A–F). Strong Int6 tissue-specific expression was also detected in the developing intestine and lens, regions that had little or no phospho-Erk expression (Figure S4). Given the observed phospho-Erk and Int6 expression in the craniofacial region, we hypothesized that some of the Int6 phenotypes, such as the jaw formation defect, might be phenocopied by repression of Erk signaling. As interpretation of MO phenotypes has recently been complicated by the identification of MO-induced p53-dependent craniofacial defects [22], we used an alternative approach – the highly selective, clinically active MEK inhibitor CI-1040 [23] – to reduce Mek signaling in zebrafish. We added the drug at 4 hpf at a concentration of 0.25, 0.5, and 1.0 µM, and confirmed loss of phospho-Erk expression by Western blot analysis (data not shown). Notably, the addition of CI-1040 caused a dose-dependent loss of the posterior structures of the embryo, such that 1.0 µM CI-1040 caused a severe anterior-posterior (AP) axis defect (Figure 4A–C), consistent with a role for FGF signaling in the development of the AP axis [24]. CI-1040 also caused loss of ceratobranchial cartilage elements, while the anterior elements – Meckel's, palatoquadrate and hyoid cartilages – were present but misshapen (Figure 3G–J), similar to the effects seen in int6 morphants and mutants.

Figure 3. Int6 and phospho-Erk expression in the developing zebrafish embryo, and pharmacological inhibition of Mek alters ceratobrancial (CB) arches.

(A–F). Immuno-histochemistry of Int6 and phospho-Erk in the developing craniofacial tissues, counter stained with hematoxylin, and phospho-histone H3 to show cycling cells. (G, H) Ventral whole mount views of Alcian blue stained pharyngeal cartilages show loss of ceratobrancial arches 1–5 and a reduction of Meckel's (M), palatoquadrate (PQ) and ceratohyal (CH) cartilages in 4 dpf embryos treated with 0.5 uM CI-1040. (I, J) Sections of 4 dpf embryos hematoxylin and eosin stained after 0.5 uM CI-1040 treatment reveals loss of CB arches 1–5 (brackets). E, Ethmoid plate; PC, Parachordal cartilage.

Figure 4. Int6 and Mek signaling interact in vivo.

(A–C). Only embryos treated with the 1.0 µM CI-1040, and not 0.25 µM, show a loss of posterior structures, in contrast to (D) int6 morphants (int6 MO 0.25 ng). (E, F) In combination with 0.25 µM of CI-1040, 0.25 µg of int6 MO causes a dramatic alteration of the anterior-posterior axis.

To further elucidate the biological relevance of Int6 and Mek signaling, we took advantage of the ease with which signaling pathways can be altered pharmacologically in specific genetic contexts in the zebrafish system. We reasoned that if Int6 contributes to activation of Mek signaling, then embryos with reduced Int6 should be hypersensitive to low doses of the MEK inhibitor CI-1040. In control embryos treated with 0.25 µM CI-1040, no changes in the anterior-posterior axis were detected (Figure 4B). In addition, int6 morphants generated by low doses of MO (0.25 ng) did not have an altered AP axis (Figure 4D). In contrast, in combination with low doses of CI-1040, the low dose int6 morphant showed a severely enhanced AP axis phenotype (Figure 4E). Taken together, these data provide further evidence that int6 may play a role in modulating MEK signaling in vivo.

Discussion

Activated in most cancers, the MAPK signaling pathway is among the most attractive targets for novel anti-cancer therapies [23]. Like MAPK signaling pathways, most of the Int pathways - Wnt, Fgf, and Notch - are conserved regulators of development that are frequently activated to promote oncogenesis. We provide evidence that, like other Int gene products, Int6 is required for vertebrate development (Figure 1), in part by providing a novel layer of MAPK signal transduction regulation (Figure 2). With the wide range of cellular activities attributed to INT6, the mechanistic detail of this control remains to be understood; our early investigations indicate reduction of MEK1 in INT6-siRNA treated mammalian cells is not dependent on the proteasome (M.G. & C.J.N., unpublished data), making direct MEK1 regulation by INT6-dependent translation a possibility.

Recently, importance of RAS, RAF and MEK in human disease has been extended beyond cancer by the discovery that human germ-line mutations in these genes cause the LEOPARD-Noonan family of syndromes [25]. Detailed immunohistochemical studies in mice have identified highly regulated, specific domains of discrete and dynamic ERK phosphorylation throughout development, including the pharyngeal arches and limb buds [26]. In the first Int6 protein expression studies in a whole developing animal, we show that Int6 has regionally overlapping domains of protein expression with phospho-Erk, primarily in the craniofacial region (Figure 3, Figure S4). Lending biological significance to these observations, we show that phenotypic characteristics are shared between the loss of Int6 and inhibition of Mek activity (Figure 3). In addition, partial loss of Int6 causes embryos to be highly sensitive to a mildly compromising dose of Mek inhibition, revealing an in vivo interaction between Int6 protein expression and developmental Mek-Erk signaling (Figure 4). As early over-expression of Ras-Raf-Mek signaling causes morphologic defects, we are currently generating transgenic lines that allow temporal control of Mek signaling, which will be a valuable tool for deeper genetic dissection of the Int6-Mek-Erk relationship in vivo. It will be critical in future studies to establish if Int6 is capable of controlling both Mek1 and Mek2; our initial MO studies indicate that MEK2 may have a specific role in melanocyte migration (C.A. & E.E.P, unpublished data), raising the possibility that the pigment cell migration defects observed in the int6 morphants also reflect altered MEK signaling.

FGF signaling is crucial for skeletal development, exemplified by the mutations that disrupt FGF signaling in human genetic skeletal abnormality syndromes [27]. In the developing mouse embryo, most phospho-ERK domains overlap with FGF signaling domains [26]. FGF signaling molecules are candidates for upstream activation of the Int6-moderated Mek-Erk signaling that shapes the craniofacial skeleton in vertebrates [28], [29], and candidate downstream targets of Int6-Mek-Erk signaling include the chondrocyte differentiation transcription factor Sox9, which requires Mek activity for transcriptional activity [30]. We also note that erk2, but not erk1, is specifically expressed in the pharyngeal arches in two-day old zebrafish embryos [31], possibly suggesting that Int6-Mek modulation in the developing craniofacial region may specifically signal through targets of Erk2.

Relating the Int6 modulation of Mek-Erk signaling to cancer development is a new angle for future investigation. One possibility is that in MMTV induced mammary tumors, the truncated Int-6 protein may act as an oncogene by altering MEK-ERK signaling. We propose that the diverse cellular locations of Int6, combined with the temporal expression and localization of Mek1/2 and Erk1/2, may result in fine-tuning of Mek-Erk signaling pathways in specific tissues during development, and may have important implications for the role of INT6 in tumorigenesis.

Methods

Zebrafish husbandry and morpholino studies

Zerbafish (Danio rerio) lines AB, AB*, and AB*-TPL were raised and staged as described [32], [33]. MOs (Table 1) were designed by and purchased from Gene Tools, LLC (USA), and 1 ng injected into one-cell stage embryos.

Table 1. Oligonucleotides used in this study.

| Method | Symbol | Oligonucleotide |

| Morpholino | ||

| Control | con MO | 5′ CCTCTTACCTCAGTTACAATTTATA |

| int6 Translation block | int-6 MO | 5′ GGTCAGATCGTACTCCGCCATGATG |

| int6 5-base pair mismatch | int-6 5MM | 5′ GGTgAGATCcTAgTCCGCgATcATG |

| siRNA | ||

| INT6 sense siRNA (si) | INT6-siRNA | 5′ GAACCACAGUGGUUGCACAUU |

| INT6 reverse siRNA (R) | R | 5′ UUACACGUUGGUGACACCAAG |

| RT-PCR primers | ||

| MEK1 forward | 5′ ATTATTGTTCCCCTAAGTGGATTG | |

| MEK1 reverse | 5′ TTACAACAGCATTGGTACTTGGAT | |

| INT6 forward | 5′ ATGGCGGAGTACGACTTGACT | |

| INT6 reverse | 5′ TCAGTAGAAGCCAGAATCTTGAGT | |

| Actin forward | 5′ CGTGATGGTGGGCATGGGTCA | |

| Actin reverse | 5′ CTTAATGTCACGCACGATTTCC | |

Phenotype analysis

Phenotype analysis were performed as described: cell cycle studies [34]; alcian blue staining [35]; probe synthesis and whole-mount in-situ hybridizations [36]. cDNA probes for neural crest markers were the kind gift of David Raible (University of Washington, USA). Polyadenylated int6 mRNA was generated using Ambion mMessage mMachine (#1340).

Cell culture and RT-PCR analysis

MDA-MB-231 cells were grown and transfected as described [19] using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) with si-oligonucleotides (Table 1; Eurogentec) at a final concentration of 100 nM in Optimem (Gibco). Forty-eight hours after transfection total RNA was isolated (RNeasy Mini Kit; Qiagen) and one-step RT-PCR reactions (Qiagen) accomplished using specific primers (Table 1).

Immunoblotting

Whole-cell lysates and zebrafish extracts were generated [31], [19] and immunohistochemistry was performed as described [36]. Antibodies used as in Table 2.

Table 2. Primary antibodies used in this study.

| Antibody | Source | Working dilution |

| anti-Phospho-Histone H3 (ser 10) #9706 | Cell Signaling Technology | 1∶1000 western blot 1∶100 immunohistochemistry |

| anti-Phospho-p44/42 MAPK #9160 | Cell Signaling Technology | 1∶1000 western blot 1∶100 immunohistochemistry |

| anti-Int6 CN24 | Watkins and Norbury, 2004 | 1∶500 western blot 1∶50 immunohistochemistry |

| anti-α-tubulin | K. Gull, Oxford | 1∶5000 western blot |

| anti-BAX N-20 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | 1∶1000 western blot |

| anti-MEK1 H-8 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | 1∶2000 western blot |

| anti-actin N-20 | Sigma | 1∶4000 western blot |

Supporting Information

Cell cycle analysis of int6 morphants. Whole-mount immunohistochemistry with the late G2/M phase marker, phospho-histone H3 shows only slightly reduced numbers of cells in late G2/M phase in the int6 morphant compared to the control. Similarly, DNA content as measured by flow cytometry reveals only a slight reduction of cells in G2/M phase in the int6 morphant. Thus, we find that loss of Int6 in normal vertebrate cells (as well as in additional human cancer cell lines, M.G. & C.J.N. unpublished data) does not appear result in an accumulation of cells in G2/M progression.

(4.75 MB TIF)

Lateral views of in situ hybridization of neural crest markers in control and int6 morphants, revealing no change in cell number or migration as indicated by the apparently normal expression of dlx2 (stages 6–36 hpf, examined at two hour intervals), nor of early markers of NCC and melanocytes, such as sox10, crestin, snail and mitfa (24 hpf) in int6 morphants. These observations were extended by examination of a transgenic sox10-GFP line (1) revealing unaltered GFP-expressing NC-derived cells in int6 morphants within the first 48 hpf, but a loss of GFP expressing differentiated pharyngeal arches 3–7 by 3 dpf (data not shown).

(40.41 MB TIF)

Development of the pharyngeal arches in the developing control (A–C) and (D–F) int6 morphant animals. Note the loss of pharyngeal arches (A, bracket) in the int6 morphants (bracket). Sections were stained with methylene blue. Anterior to the left.

(14.09 MB TIF)

Immunohistochemistry of Int6 and phospho-Erk staining in 4 dpf embryos. (A, B) While Int6 and phospho-Erk signaling overlap in the craniofacial region, they also have distinct patterns, for example in the eye and (C, D) gut. We note that while Int6 and phospho-Erk have overlapping domains of expression in the craniofacial region, Int6 staining in the craniofacial region was stronger than phospho-Erk, and phospho-Erk staining was limited to specific tissues within the craniofacial region. M, Meckel's; E: Ethmoid plate; CH, ceratohyal; CB, ceratobrancial. Sagittal section, anterior to the left.

(17.60 MB TIF)

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to N. Hopkins, A. Amsterdam and S. Farrington for the int6hi2470 line; R. Marais and C. Marshall for CI-1040; D. Raible for DNA constructs; K. Gull for anti-tubulin antibodies; E. Prichard for additional CI-1040 observations; D. Faratian for help with immunohistochemistry; B. Morgan for assistance with manuscript preparation; L. Poulton for critical reading of the manuscript; and N. Hastie and D. Harrison for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: This work was funded by a MRC grant to EEP, and by grants from CRUK and the AICR to CJN. Funders had no role in the design or conduct of the study, in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data, or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Callahan R, Smith GH. MMTV-induced mammary tumorigenesis: gene discovery, progression to malignancy and cellular pathways. Ongogene. 2000;19:992–1001. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nusse R, Varmus HE. Many Tumors Induced by the Mouse Mammary Tumor Virus Contain a Provirus Integrated in the Same Region of the Host Genome. Cell. 1982;31:99–109. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90409-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rijsewijk F, Schuermann M, Wagenaar E, Parren P, Weigel D, et al. The Drosophila homolog of the mouse mammary oncogene int-1 is identical to the segment polarity gene wingless. Cell. 1987;50:649–657. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90038-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clevers H. Wnt/ß-Catenin Signaling in Development and Disease. Cell. 2006;3:469–480. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tekmal RR, Keshava N. Role of MMTV integration locus cellular genes in breast cancer. Front Biosci. 1997;379:519–526. doi: 10.2741/a209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asano K, Merrick WC, Hershey JW. The translation initiation factor eIF3-p48 subunit is encoded by int-6, a site of frequent integration by the mouse mammary tumor virus genome. J Biol Chem. 1997;19:23477–23480. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mayeur GL, Hershey JW. Malignant transformation by the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit p48 (eIF3e). FEBS Lett. 2002;514:49–54. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02307-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rasmussen SB, Kordon E, Callahan R, Smith GH. Evidence for the transforming activity of a truncated Int6 gene, in vitro. Oncogene. 2001;20:5291–5301. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mack DL, Boulanger CA, Callahan R, Smith GH. Expression of truncated Int6/eIF3e in mammary alveolar epithelium leads to persistent hyperplasia and tumorigenesis. Br Can Res, 2007;4:42. doi: 10.1186/bcr1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buttitta, et al. Int6 Expression Can Predict Survival in Early-Stage Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:3198–3204. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marchetti A, Buttitta F, Pellegrini S, Bertacca G, Callahan R. Reduced expression of INT-6/eIF3-p48 in human tumors. Inter J Onco. 2001;18:175–179. doi: 10.3892/ijo.18.1.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Traicoff Chung JY, Braunschweig T, Mazo I, Shu Y, et al. Expression of EIF3-p48/INT6, TID1 and Patched in cancer, a profiling of multiple tumor types and correlation of expression. J Biomed Sci. 2007;14:395–405. doi: 10.1007/s11373-007-9149-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yen HC, Chang EC. INT6–a link between the proteasome and tumorigenesis. Cell Cycle. 2003;2:81–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crane R, Craig R, Murray R, Dunand-Sauthier I, Humphrey T, et al. A fission yeast homolog of Int-6, the mammalian oncoprotein and eIF3 subunit, induces drug resistance when overexpressed. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;10:3993–4003. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.11.3993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jenkins CC, Mata J, Crane RF, Thomas B, Akoulitchev A, et al. Activation of AP-1-dependent transcription by a truncated translation initiation factor. Eukaryotic Cell. 2005;11:1840–1850. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.11.1840-1850.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morris C, Jalinot P. Silencing of human Int-6 impairs mitosis progression and inhibits cyclin B-Cdk1 activation. Oncogene. 2005;24:1203–1211. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buchsbaum S, Morris C, Bochard V, Jalinot P. Human INT6 interacts with MCM7 and regulates its stability during S phase of the cell cycle. Oncogene. 2007:1–13. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen L, Uchida K, Endler A, Shibasaki F. Mammalian tumor suppressor Int6 specifically targets hypoxia inducible factor 2 alpha for degradation by hypoxia- and pVHL-independent regulation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:12707–12716. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700423200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morris C, Wittmann J, Jack HM, Jalinot P. Human INT6/eIF3e is required for nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. EMBO Rep. 2007. 2007;8:596–602. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watkins SJ, Norbury CJ. Cell cycle-related variation in subcellular localization of eIF3e/INT6 in human fibroblasts. Cell Prolif. 2004;37:149–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2004.00305.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou C, Arslan F, Wee S, Krishnan S, Ivanov AR, Oliva A, Leatherwood J, Wolf DA. PCI proteins eIF3e and eIF3m define distinct translation initiation factor 3 complexes. BMC Biology. 2005;3:14. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-3-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robu ME, Larson JD, Nasevicius A, Beiraghi S, Brenner C, et al. p53 Activation by knockdown technologies. PloS Genetics. 2007;3:0787–0801. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sebolt-Leopold JS, Herrera R. Targeting the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade to treat cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:937–947. doi: 10.1038/nrc1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schier AF, Talbot WS. Molecular genetics of axis formation in zebrafish. Annu Rev Genet. 2005;39:561–613. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.37.110801.143752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bentires-Alj M, Kontaridis MI, Neel BG. Stops along the RAS pathway in human genetic disease. Nature Medicine. 2006;12:283–285. doi: 10.1038/nm0306-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corson LB, Yamanaka Y, Lai KM, Rossant J. Spatial and temporal patterns of ERK signaling during mouse embryogenesis. Development. 2003;130:4527–4537. doi: 10.1242/dev.00669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilkie AO. Bad Bones, absent smell, selfish testes: the pleiotropic consequences of human FGF receptor mutations. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16:187–203. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldring MB, Tsuchimochi K, Ijiri K. The Control of Chondrogenesis. J Cell Biochem, 2006;97:33–44. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Graham A, Okabe M, Quinlan R. The role of the endoderm in the development and evolution of the pharyngeal arches. J Anat. 2005;207:479–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2005.00472.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murakami S, Kan M, McKeehan WL, de Crombrugghe B. Up-regulation of the chondrogenic Sox9 gene by fibroblast growth factors is mediated by the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. PNAS, 2000;97:113–118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krens SF, He S, Spaink HP, Snaar-Jagalska BE. Characterization and expression patterns of the MAPK family in zebrafish. Gene Exp Patterns. 2006;6:1019–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Westerfield M. The Zebrafish Book. The University of Oregon Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kimmel CB, Ballard WW, Kimmel SR, Ullmann B, Schilling TF. Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 1995;203:253–310. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002030302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shepard JL, Stern HM, Pfaff KL, Amatruda JF. Analysis of the cell cycle in zebrafish embryos. Methods Cell Biol. 2004;76:109–125. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(04)76007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Javidan Y, Schilling TF. Development of cartilage and bone. Methods Cell Biol, 2004;76:415–436. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(04)76018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nusslein-Volhard C, Dahm R. A Practical Approach. London: Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patton EE, Widlund HR, Kutok JL, Kopani KR, Amatruda JF, et al. BRAF mutations are sufficient to promote nevi formation and cooperate with p53 in the genesis of melanoma. Curr Biol, 2005;15:249–254. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Cell cycle analysis of int6 morphants. Whole-mount immunohistochemistry with the late G2/M phase marker, phospho-histone H3 shows only slightly reduced numbers of cells in late G2/M phase in the int6 morphant compared to the control. Similarly, DNA content as measured by flow cytometry reveals only a slight reduction of cells in G2/M phase in the int6 morphant. Thus, we find that loss of Int6 in normal vertebrate cells (as well as in additional human cancer cell lines, M.G. & C.J.N. unpublished data) does not appear result in an accumulation of cells in G2/M progression.

(4.75 MB TIF)

Lateral views of in situ hybridization of neural crest markers in control and int6 morphants, revealing no change in cell number or migration as indicated by the apparently normal expression of dlx2 (stages 6–36 hpf, examined at two hour intervals), nor of early markers of NCC and melanocytes, such as sox10, crestin, snail and mitfa (24 hpf) in int6 morphants. These observations were extended by examination of a transgenic sox10-GFP line (1) revealing unaltered GFP-expressing NC-derived cells in int6 morphants within the first 48 hpf, but a loss of GFP expressing differentiated pharyngeal arches 3–7 by 3 dpf (data not shown).

(40.41 MB TIF)

Development of the pharyngeal arches in the developing control (A–C) and (D–F) int6 morphant animals. Note the loss of pharyngeal arches (A, bracket) in the int6 morphants (bracket). Sections were stained with methylene blue. Anterior to the left.

(14.09 MB TIF)

Immunohistochemistry of Int6 and phospho-Erk staining in 4 dpf embryos. (A, B) While Int6 and phospho-Erk signaling overlap in the craniofacial region, they also have distinct patterns, for example in the eye and (C, D) gut. We note that while Int6 and phospho-Erk have overlapping domains of expression in the craniofacial region, Int6 staining in the craniofacial region was stronger than phospho-Erk, and phospho-Erk staining was limited to specific tissues within the craniofacial region. M, Meckel's; E: Ethmoid plate; CH, ceratohyal; CB, ceratobrancial. Sagittal section, anterior to the left.

(17.60 MB TIF)