Abstract

We describe an efficient method for introducing and analyzing a comprehensive set of mutations in a cloned gene to map its functional organization. The technique, genetic footprinting, uses a retroviral integrase to generate a comprehensive library of mutants, each of which bears a single insertion of a defined oligonucleotide at a random position in the gene of interest. This mutant library is selected for gene function en masse. DNA samples are isolated from the library both before and after selection, and the mutations represented in each sample are then analyzed. The analysis is designed so that a mutation at a particular location gives rise to an electrophoretic band of discrete mobility. For the whole library, this results in a ladder of bands, each band representing a specific mutation. Mutants in which the inserted sequence disrupts a feature that is required for the selected function, ipso facto, fail the selection. The corresponding bands are therefore absent from the ladder of bands obtained from the library after selection, giving rise to a footprint representing features of the gene that are essential for the selected function. Because the sequence of the inserted oligonucleotide is known, and its position can be inferred precisely from the electrophoretic mobility of the corresponding band, the precise location and sequence of mutations that disrupt gene function can be determined without isolating or sequencing individual mutants. This method should be generally applicable for saturation mutagenesis and high-resolution functional mapping of cloned DNA sequences.

Mutagenesis, followed by analysis of the functional attributes retained or lost by the resulting mutants, is an essential strategy for analyzing the structure and function of a gene. Current methods of mutagenesis and mutant analysis fall into two broad categories. One consists of creating specific mutations followed by studying their phenotypes. The other involves creating a series of random mutations, subjecting them to a selection or screen for gene function, and then characterizing the molecular defect in each of the mutants. Both of these approaches usually involve isolating, storing, and characterizing each mutant separately, making them very time- and labor-intensive as the number of mutants increases. In this report we describe an efficient experimental procedure for construction and parallel analysis of a comprehensive set of mutations in a gene to define the important functional features of that gene.

We used a retroviral integrase, the enzyme that integrates the retroviral genome into a host chromosome, to generate an extensive pool of insertion or substitution mutations. Each mutant in the pool carried an insertion of a defined oligonucleotide at a random position in the gene of interest (Fig. 1). The entire pool of mutants was subjected to selection for gene function. DNA samples were isolated from the library of mutants both before and after selection. One convenient method for analyzing the performance of each mutant under selection employed a PCR, using one primer specific to a site in or near the gene, and a second primer corresponding to the inserted oligonucleotide. For each mutation, a PCR product of unique length was generated, the length depending only on the position of the inserted oligonucleotide in the gene. For the whole library, this resulted in a series of products of different lengths, which when run on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel, gave rise to a ladder of bands, each band representing a specific mutation. Mutants in which the inserted sequence disrupted a feature required for the selected function failed the selection. The corresponding bands were therefore absent from the ladder of PCR products obtained from the library after selection, giving rise to a genetic footprint representing features of the gene that were essential for the selected function. Because the sequence of the inserted oligonucleotide is known, and its position could be inferred precisely from the electrophoretic mobility of the corresponding bands, the precise location and sequence of mutations that disrupt gene function could be determined without isolating or sequencing individual mutants. The technique should allow efficient production and analysis of thousands of mutations in any cloned gene that can be subjected to a functional selection.

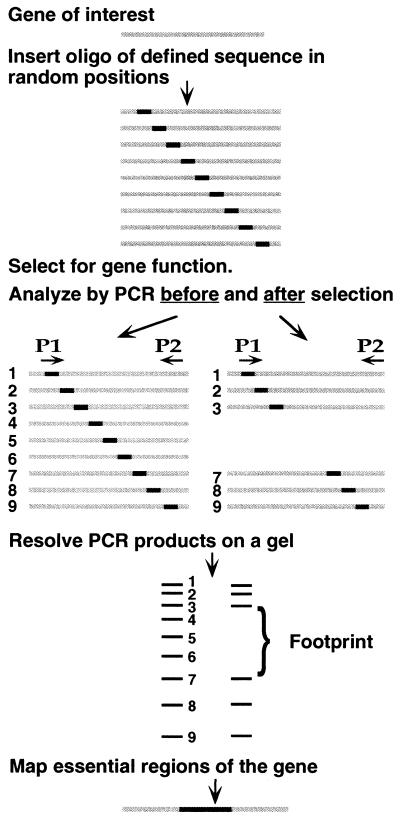

Figure 1.

The principle of genetic footprinting. Starting with a cloned gene, a comprehensive library of mutants is made by inserting a defined oligonucleotide duplex at random positions. The library of mutants is subjected to a selection for a function of the gene. DNA made from the library of mutants both before and after selection is analyzed by PCR. P1 is the primer corresponding to the inserted oligonucleotide. P2 is a labeled primer that primes from a site just outside the gene. The products run as a ladder of bands on a sequencing gel, each band corresponding to at least one independent mutation. Bands representing mutants that fail to survive the selection are absent from the corresponding ladder of PCR products, giving rise to a footprint. Comparing the sizes of the missing bands to a sequencing ladder allows precise determination of the essential feature(s) of the gene.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids Containing supF and Selection for supF Function.

The supF gene was contained in the plasmid πAN13 (894 bp) (1). Mutations in πAN13 were transformed into Escherichia coli MC1061 containing the plasmid p3, which has amber stop codons in its genes for resistance to ampicillin and tetracycline (1). Bacteria were selected for supF function by growth in liquid Luria–Bertani medium or on Luria–Bertani agar plates, containing 12.5 μg/ml ampicillin or carbenicillin and 7.5 μg/ml tetracycline. Mutant libraries were grown for 9, 16, 26, or 36 generations under selection. To generate the πchloro plasmid, the chloramphenicol-resistance gene was amplified by PCR from the plasmid pACYC184 (2), using primers 5′-ATTAATTCTAGATACCTGTGACGGAAGATCAC and 5′-ATTAATTCTAGAACCGGGTCGAATTTGCTTTC. The PCR product was purified (Qiaquick PCR purification kit, Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA), cleaved with XbaI, and subcloned into the XbaI site in the polylinker of πAN13. DNA made from a bacterial colony resistant to chloramphenicol (20 μg/ml), carbenicillin (12.5 μg/ml), and tetracycline (7.5 μg/ml) was used in the mutagenesis. πchloro mutants were expanded by growth in Luria–Bertani medium containing 20 μg/ml chloramphenicol for 9 or 18 generations.

Generation of Insertional Mutations.

Moloney murine leukemia virus (MoMLV) integrase was purified as a fusion to glutathione S-transferase (3). A single glutathione-agarose column (the first purification step in ref. 3) resulted in integrase that was sufficiently pure for this mutagenesis. The viral end (VE) oligonucleotide duplex was generated by annealing NotBsgMLVB (5′-AATGAAAGCTGCACGCGGCCGCATTCTTAT) to NotBsgMLVG (5′-ATAAGAATGCGGCCGCGTGCAGCTTTCA), heating to 95°C in 50 mM NaCl and cooling slowly to room temperature. The annealed oligonucleotides (80 nM) were incubated with 120 nM integrase in 5 mM MnCl2/20 mM Mops, pH 7.2/75 mM KCl/10 mM DTT/50 μg/ml BSA/20% (vol/vol) glycerol in a reaction volume of 100 μl for 5 min at 37°C. NaCl (final concentration of 400 mM), and 4.5 μg of a mixture of plasmids πAN13 and p3 then were added to the above (for convenience, the p3 plasmid was not separated away from πAN13) and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. The reaction was stopped with 10 mM disodium EDTA, pH 8.0/0.5% SDS/50 μg/ml proteinase K and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. Except for the high concentration of sodium chloride (see below), the reaction conditions were similar to standard in vitro reactions with MoMLV integrase and resulted in sufficient concerted integration product. However, it is quite possible that some parameters that we did not test might result in more efficient concerted integration. πAN13 plasmids that had undergone a concerted integration of two oligonucleotides, and were therefore linear (29% of total DNA), were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis from those that had only a single oligonucleotide integrated (relaxed circle, 17% of total DNA) and those that had no integrations (supercoiled DNA, 54% of total DNA). The concerted integration product was purified (Qiaquick gel extraction kit). Nick translation with Taq DNA polymerase (see below) eliminated the four-nucleotide gap flanking the integrated oligonucleotides. The resulting molecules were amplified by PCR using the oligonucleotide NotBsgMLVG, both to obtain more starting material and to select further for molecules that had undergone a concerted integration of two oligonucleotides. The PCR buffer contained 20 mM Tris·HCl (pH 8.55 at 25°C), 150 μg/ml BSA, 16 mM (NH4)2SO4, and 250 μM each dNTP. Each 100-μl reaction mixture had 3.5 mM MgCl2, 40 pmol of primer NotBsgMLVG, 1 ng of template DNA, and 2.5 units of AmpliTaq polymerase (Perkin–Elmer). Thermal cycling consisted of 5 min at 72°C for nick translation, 2 min at 94°C, followed by 30 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, and 1 min, 20 s at 78°C. Thin-walled tubes (Applied Scientific, San Francisco) or Micro-amp tubes (Perkin–Elmer) were used, in a Perkin–Elmer 9600 thermal cycler, with all ramp times set to zero. PCR products were purified (Qiaquick PCR purification kit) and cleaved with NotI (New England Biolabs). Subsequent ligation of the cohesive ends gave rise to a 36-bp insertion (50–100 ng of DNA, buffer provided by New England Biolabs and 2.5 Weiss units of T4 DNA ligase in 20 μl was incubated at 16°C for 18 h).

Analysis of Insertional Mutations by PCR.

DNA samples from the unselected and selected libraries of mutant supF were used as templates for a PCR that used the inserted VE oligonucleotide as one of the priming sites (primer 5′-GGCCGCGTGCAGCTTTCA), and a primer that hybridized to a site near or in the gene as the second priming site. For mutants generated in πAN13, the gene-specific primer was π267L (5′-GGAAAAACGCCAGCAACGCCAGC); for mutants generated in πchloro, the gene-specific primer was π858U (5′-CCTTTGATCTTTTCTACGGGGTCTG) or CAM60supF (5′-CGGTATCAACAGGGACACCAGGA). Each 20-μl reaction mixture contained PCR buffer (described above), 2 mM MgCl2, 2 ng of template DNA, 0.5 unit of AmpliTaq polymerase, and 4 pmol of each primer. One-tenth of the gene-specific primer was labeled with 32P (T4 polynucleotide kinase, New England Biolabs). Thermocycling was for 2 min at 94°C, followed by 15 cycles of 30 s at 94°C and 30 s at 72°C. An equal volume of gel-loading dye (95% deionized formamide/20 mM EDTA/0.05% xylene cyanol/0.05% bromophenol blue) was added, and samples were heated to 95°C for 5 min before loading onto a preheated 6% or 8% polyacrylamide sequencing gel, containing 7 M urea and running buffer (89 mM Tris·HCl, pH 8.5/29 mM taurine/0.5 mM EDTA).

Generation of Substitution Mutations.

Three micrograms of plasmid DNA from the chloramphenicol-selected πchloro insertion library was digested with 20 units of BsgI, in the manufacturer-supplied buffer (New England Biolabs), in a final volume of 150 μl. Twelve nanomoles of S-adenosylmethionine was added every 20 min during the 2-h digestion. DNA was extracted with phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1, vol/vol) and precipitated with ethanol. To ensure complete digestion, the DNA was subjected to a second identical round of BsgI digestion. Other type IIs enzymes, such as BpmI (New England Biolabs) and Eco57I (Fermentas-New England Biolabs), share with BsgI the ability to recognize a 6-bp sequence and to cleave 16/14 bp away from the recognition site. While we have not tested them, it is possible that they provide more accurate and complete cleavage than BsgI. The BsgI-digested plasmid DNA was ligated to a 12-bp insert generated from the self-complementary oligonucleotide 5′-TAGCATATGCTANN, where N represents an equal mixture of the four deoxynucleotides. The 3′ end of this oligonucleotide was randomized to allow base pairing to the unspecified 3′ dinucleotide overhang generated in the plasmid by BsgI digestion. The oligonucleotide was phosphorylated with T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs) and self-annealed. The annealed oligonucleotide was present in 100-fold molar excess over plasmid DNA. A 50-μl ligation reaction mixture containing 0.5–1 μg of plasmid DNA, 40 pmol of annealed oligonucleotide, a buffer provided by the manufacturer (New England Biolabs), and 12 Weiss units of T4 DNA ligase was incubated at 16°C for 18 h. The reaction mixture was extracted with phenol/chloroform and precipitated with ethanol. The ligated DNA was cleaved with the restriction enzyme NdeI, whose recognition site was unique to the replacement oligonucleotide. A 200-μl reaction mixture contained 400 units of NdeI and a buffer provided by the manufacturer (New England Biolabs). Cleaved excess oligonucleotide was removed (Qiaquick PCR purification kit). DNA was recircularized by ligation as described for insertional mutations.

Analysis of Insertion and Substitution Mutations by Restriction Endonuclease Digestion.

PCR was performed on insertional or substitution mutation libraries, using the primers π858U and CAM60supF (sequences given above), with one of the two primers radiolabeled. To generate a sizing ladder using sequenced substitution mutation clones, the π858U primer was radiolabeled and used for PCR in concert with unlabeled primer π267L. Duplicate 100-μl PCR mixtures contained PCR buffer (see above), 3.5 mM MgCl2, 20 ng of template DNA, 2.5 units of AmpliTaq DNA polymerase, and 10 pmol each of labeled and unlabeled primer. Thermal cycling was for 2 min at 94°C, followed by 10 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 20 s at 68°C, and 30 s at 72°C. Duplicate reactions were pooled, concentrated (Qiaquick PCR purification kit), and purified by electrophoresis through 1% agarose and band excision (Qiaquick gel extraction kit). Purified PCR products were digested with NotI (insertional mutants) or with NdeI (substitution mutants): 1.5 units of enzyme per μl in the manufacturer-supplied buffer (New England Biolabs). Digestion products were analyzed by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (described above).

RESULTS

General Strategy for Introducing Mutations.

To make a diverse set of insertional and substitution mutations in a gene (see Fig. 2 and Materials and Methods), we used MoMLV integrase, the retroviral enzyme that integrates the viral genome into a host chromosome. Integrase can carry out a similar reaction in vitro, integrating a pair of oligonucleotides, representing the two ends of the viral DNA, into a circular DNA molecule containing a target gene (3–6). The oligonucleotides used for these experiments (VE oligonucleotides) contained the sequence recognized by integrase as a model viral DNA end, and sites for restriction endonucleases NotI and BsgI. Cleavage of the integration products with NotI generated cohesive ends, which could be ligated to produce a circular DNA containing a 36-bp insertion, 32 bp of which consisted of an inverted repeat (Fig. 2B). A second strategy allowed insertions of any defined size and sequence to be introduced, either as net insertions or as substitutions for wild-type sequence. This method involved cutting the original insertions with BsgI, a type IIs restriction enzyme that recognizes a site in the VE oligonucleotide, but cleaves 16/14 nucleotides away, in the target gene sequences that flank the inserted oligonucleotide. Cleavage directed by the two inserted BsgI sites resulted in a deletion of 12 bp from the gene. Ligation of this cleavage product in the presence of an oligonucleotide duplex of the same effective length resulted in a block substitution. In the case of a protein-encoding gene, this would preserve the translational reading frame and the overall length of the mutant polypeptide.

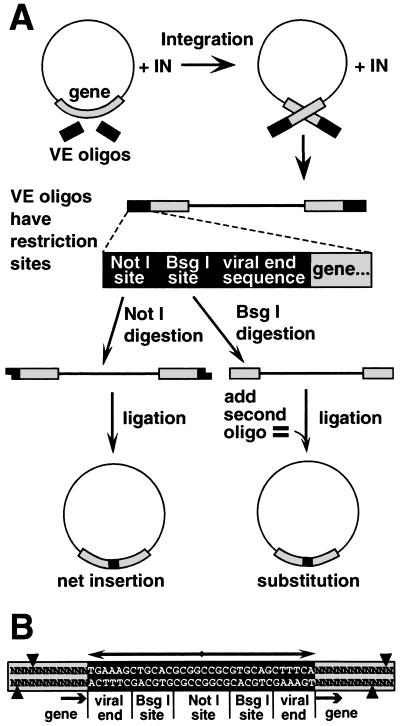

Figure 2.

Strategy for making random insertions. (A) MoMLV integrase inserted oligonucleotide duplexes (VE oligonucleotides) containing terminal sequences from MoMLV DNA ends into diverse sites in a plasmid. Linear DNA products of concerted integration of the VE oligonucleotides were purified and digested with NotI. Intramolecular ligation of the resulting cohesive ends produced a 36-bp insertion in the gene, or elsewhere in the plasmid. Digestion of the concerted integration product with BsgI (lower right) resulted in excision of the integrated oligonucleotide duplex, along with 12 bp of the flanking DNA. (B) Sequence of the insertion mutation and flanking target DNA. Each insertion has a stereotyped structure composed of a 32-bp palindrome (double-headed arrow), containing a NotI site, two BsgI sites, and two copies of sequences representing the ends of MoMLV DNA. Arrows mark the integrase-generated four-base duplication of target DNA sequence. Cleavage directed by the two BsgI sites is depicted by arrowheads, and typically resulted in a 12-bp deletion in the target gene.

Insertional Mutations in supF.

We made a library of insertional mutations in the E. coli supF suppressor tRNA gene, carried in the plasmid πAN13 (894 bp). The supF tRNA translates amber stop codons, adding tyrosine to a polypeptide chain. supF was chosen because its functional organization has been characterized (7) and because its small size (200 bp) facilitated optimization of the technique. Insertional mutations were introduced throughout πAN13. The resulting pool of mutants was transformed into E. coli MC1061 containing the plasmid p3, which has amber stop codons in its genes for resistance to ampicillin and tetracycline (1). Growth of the transformants in the presence of ampicillin and tetracycline depended upon functional supF tRNA, allowing selection for supF function.

DNA was prepared from both the unselected and selected pools of mutagenized πAN13 plasmids. The samples were analyzed by PCR, using a labeled primer (π267L) that hybridized to a site about 160 bp upstream of the start site of the supF gene (see Fig. 4). The second primer was complementary to the inserted oligonucleotide. A ladder of bands was seen in the lane containing PCR products from the unselected DNA (Fig. 3, lane 1), each band representing at least one insertion at a specific site in the target plasmid. The size of the library was such that each internucleotide site in the plasmid was represented by an average of more than 200 independent mutant clones. The lane representing the selected pool showed two prominent footprints (Fig. 3, lane 2). Footprint 1 corresponded to insertions that mapped to sites between 46 and 126 nucleotides downstream of the transcription start site, and footprint 2 corresponded to insertions that mapped to sites between 9 and 29 nucleotides upstream of the transcription start site (Fig. 4). Most of the bands seen in regions outside the footprints in the unselected pool (Fig. 3, lane 1) also were seen in the lane representing the selected pool (Fig. 3, lane 2). Two alternative primers, one priming at a site in the 5′-pre-tRNA sequence, and the other priming in the opposite direction at a site downstream of the supF gene, were used in a similar analysis. The resulting footprints mapped to sites identical to those identified in Fig. 3A (data not shown).

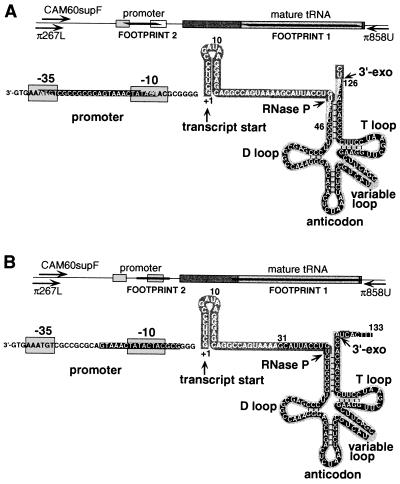

Figure 4.

The structure of supF and a map of its essential features. The supF tRNA is transcribed as a 128-nucleotide precursor, which is cleaved by RNase P and a 3′-exonuclease (3′-exo) to generate the 85-nucleotide mature tRNA. To the left of the RNA transcript are the promoter elements of the gene. A linear representation of the gene is shown at the top. Mature tRNA sequences are shown in pale gray; precursor sequences that are removed upon processing are shown in darker gray. Footprints are shown in black. Primers used to generate the footprint shown in Fig. 3 hybridized to a site located 160 bp (primer-π267L) or 141 bp (CAM60supF) upstream, or 183 bp downstream (π858U), of the transcription start site. (A) Footprints from the 36-bp insertional mutation library. Footprint 1 extends from nucleotide 46 to nucleotide 126 of the transcript. Footprint 2 extends from nucleotide −9 to nucleotide −29 in the promoter region. (B) Footprints from the substitution mutation library. Footprint 1 extends from nucleotide 35 to nucleotide 129 in the mature tRNA. Footprint 2 in the promoter region is represented by the absence of three bands in positions −7, −9, and −12. The exact boundaries of footprints in this illustration are determined by the set of rules chosen to define them. In A, nucleotides that are partially covered by the footprint represent those that are duplicated by integration events. In B, edges of the footprint are drawn at the internucleotide site corresponding to the right edge of the insertion. In regions where integration was infrequent, the footprint boundary could lie between a band that was retained after selection and one that was a few nucleotides away and was not retained. In such cases, we have chosen to define the margins of the footprints by the nearest bands retained after selection.

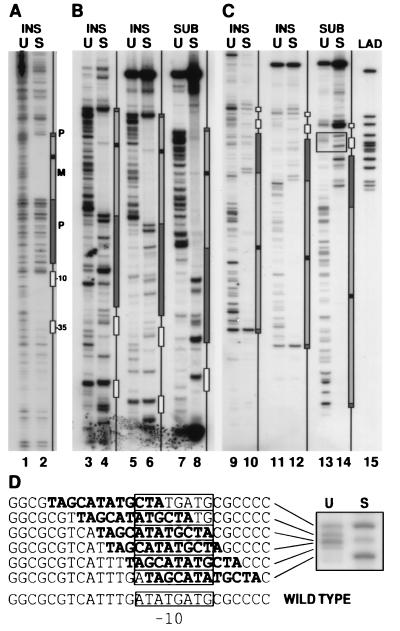

Figure 3.

Genetic footprinting of supF. (A) Analysis of 36-bp insertional mutations in the plasmid πAN13. DNA from the unselected (U) and selected (S) libraries of mutant supF was used as template for a PCR containing a primer complementary to the insert oligonucleotide, paired with a radiolabeled primer complementary to a region 160 bp upstream of the transcription start site (π267L). A schematic diagram of the supF gene is shown to the right, aligned with the corresponding PCR products. Sequenced plasmid DNA and PCR products from selected sequenced mutations were run adjacent to the footprinted DNA as molecular weight markers and were used to draw the boxes representing various regions of the supF gene (boxes marked −10 and −35 correspond to promoter elements; P, regions of precursor tRNA that are removed upon processing; M, mature tRNA. Black box within the mature tRNA corresponds to the variable loop). (B and C) Analysis of libraries of 36-bp insertional (INS) or 12-bp substitution (SUB) mutations in the plasmid πchloro. In B, the labeled primer (CAM60supF) was complementary to a region 141 bp upstream of the transcription start site; in C, the labeled primer (π858U) was complementary to a region 183 bp downstream of the start site. In lanes 3, 4, 9, and 10, insertional mutants were analyzed by a PCR in which the inserted sequence served as a priming site, as in A. In lanes 5–8 and 11–14, PCR products generated using primers π858U and CAM60supF (one of which was labeled as indicated above) were digested with a restriction endonuclease, whose recognition sequence was unique to the inserted sequence. The ladder (LAD) in lane 15 was generated by pooling 12 unique sequenced clones of replacement mutants that were made in the plasmid πAN13. Ladder DNA was PCR amplified with primer π267L and labeled primer π858U, and digested with a restriction endonuclease as described. (D) The boxed region from lanes 13 and 14 is enlarged to show the PCR products corresponding to substitution mutants replacing all or part of the −10 element. The sequence corresponding to each mutant is indicated to the left with the substituted sequence indicated in boldface type. The wild-type sequence of this region is shown at the bottom, with the −10 element indicated by a box.

These results are in accord with previously reported structure–function analyses of supF tRNA (8–10). The supF tRNA is synthesized as a larger pre-tRNA, which then is processed at the 5′ end of the tRNA by RNase P, and at the 3′ end by a 3′-exonuclease, to give rise to the mature tRNA (8, 11) (see Fig. 4). Footprint 1 encompassed most of the sequence encoding the mature tRNA (Fig. 4). The mature tRNA, a small (85-nucleotide), compactly folded structure, tolerated a 36-bp insert only in the variable loop (see band within footprint 1, Fig. 3, lane 4), which varies considerably in length among natural tRNAs (12). There are canonical promoter elements in the −10 and −35 positions upstream of the transcription unit. These sequences, and the distance between them, are important for promoter activity, and thus would be expected to be sensitive to large insertions. Footprint 2 was consistent with this expectation, spanning the −10 promoter element and the region between the two promoter elements. There was only a partial depletion of bands representing insertions in the −35 promoter box. This might be explained by the similarities between the sequence of the −35 promoter box and the terminal sequences of the VE oligonucleotide (GAAATGT and GAAAGT, respectively).

In integrating viral DNA, MoMLV integrase joins the 3′ ends of viral DNA to 5′-phosphates staggered by four base pairs in the target DNA, resulting in four-base gaps flanking the newly integrated viral DNA (13). Repair of the gaps results in duplication of these four bases. The fidelity of the integration process in generating a precise 4-bp duplication is critical to allowing a simple interpretation of the footprints, because we rely entirely on the size of the PCR product to infer the sequence of the corresponding mutation. The fidelity of this duplication, in an in vitro reaction using oligonucleotides as models of the viral DNA ends, has not previously been investigated. We sequenced 39 mutant clones that had survived selection to determine if each mutation had the stereotyped structure expected for inserts made by MoMLV integrase. Ninety-five percent of mutations (37 of 39) had the expected structure, i.e., they were flanked by a duplication of 4 bp of target DNA. Five percent (2 of 39) contained a 3-bp duplication. As previously reported for avian myeloblastosis virus and HIV integrases (14, 15), the fidelity depended on the salt concentration of the integration reaction. When the salt in the reaction consisted of 75 mM potassium chloride, only 66% of mutations had the expected structure. When 400 mM sodium chloride was added, in addition to the 75 mM of potassium chloride, 95% of mutations had the expected structure.

Substitution Mutations.

A second strategy (lower right of Fig. 2A and Materials and Methods) allowed us to introduce an oligonucleotide duplex of any defined length and sequence at diverse positions in the gene. To facilitate amplification of mutant libraries, we constructed a plasmid, πchloro, which contained a second selectable marker, for chloramphenicol resistance (CAMR), in addition to supF. Thirty-six-base-pair insertional mutations were introduced in this plasmid, using the VE oligonucleotides as described. Transformed bacteria containing the resulting mutagenized plasmids were grown in the presence of chloramphenicol. This allowed for expansion of the mutagenized plasmids, including those containing mutations in supF. The insertional mutations then were converted to substitution mutations by cleavage with BsgI, followed by ligation to a second oligonucleotide of desired length and sequence. The resulting mutant library contained 12-bp substitutions of wild-type sequence with that of the specific oligonucleotide duplex. The library was selected for supF function as before.

Because 12 nucleotides is too short for optimal performance as a specific PCR priming site, an alternative strategy was used for footprinting. The oligonucleotide used to make the block substitutions contained an NdeI restriction endonuclease site. A 333-bp fragment containing supF was amplified from the unselected or selected pools of mutants, using two flanking primers, one of which was radiolabeled. The PCR products then were digested with NdeI, producing a ladder of products analogous to those generated with the previous method (Fig. 3, lanes 7, 8, 13, and 14). This alternative method of analysis gave results almost identical to the previous method, when tested on the library containing the 36-bp insertion mutations (Fig. 3, compare lanes 3 and 4 with lanes 5 and 6, respectively, and lanes 9 and 10 with lanes 11 and 12, respectively). The footprint observed for the substitution mutations extended into the RNA precursor sequences 5′ to the sequences encoding the mature tRNA molecule, while the footprint observed for the larger 36-nucleotide insertions mostly was confined to the sequences of the mature tRNA (Fig. 4). Perhaps the hairpin structure of the RNA segment introduced by the larger insertions minimized disruption of the precursor. Alternatively, the duplication of the four bases on each side of the inserted sequence may have ameliorated the effects of the insertion. In contrast, in the promoter region, the substitution mutations were better tolerated than the 36-bp insertions. This might be explained by the considerable variation tolerated in bacterial promoter sequences, and by the A+T richness of the sequence chosen for the substitutions (Fig. 3D). A 109-bp deletion mutation in supF that removes the entire promoter region has been reported to retain supF activity (10).

The population of mutants selected in the presence of chloramphenicol—i.e., without selection for supF—showed a reverse footprint—an enhancement of bands in the region corresponding to the mature tRNA (Fig. 3, lanes 3, 5, and 7). This was not unexpected, because supF prevents termination of translation at amber codons and therefore is deleterious to cells that express it. The enhanced bands represent mutations that disrupted supF function and thus relieved this deleterious effect.

We sequenced 33 clones from the library of substitution mutations. Seventy percent (23 of 33) of these had the expected 12-bp deletion in the gene. The remaining 30% (10 of 33) had aberrant deletions, of 11 bp (12%), 13 bp (6%), 14 bp (9%), and 33 bp (3%). The inserted sequence was the expected one in each case. Based on sequencing of insertional mutations, aberrant integration events would account for about 5% of the unexpected deletions. The others most likely were generated by aberrant activity of BsgI or a contaminant in the BsgI or DNA ligase preparations. Nevertheless, the majority of the mutations had the expected structure, which allowed reliable analysis. In the case of a protein-encoding gene, the 30% nonstandard deletions would lead to frame-shift mutations and therefore usually to a phenotype more severe than that of a simple substitution mutation. Rare cases where the aberrant mutation resulted in a less severe defect than the canonical substitution, or a gain of function, could lead to misinterpretation of the footprinting data.

DISCUSSION

The power of genetic footprinting lies in the ability to make and analyze a large set of molecularly defined mutations in parallel. Using transposons to make large insertions in genes in vivo, the method can be applied to entire genomes to identify candidate genes involved in specific processes (16, 17). Alternatively, it can be applied at high resolution to individual genes or even to very small sequences—e.g., to identify sequences regulating gene expression, which are typically only a few base pairs in length (i.e., footprint 2). While conceptually similar, the experimental methods for genetic footprinting of genes and genomes are very different.

A key advantage of genetic footprinting is that it does not require mutants to be recovered or isolated to recognize their effect on gene function, because their presence in the initial pool of mutants, and their failure to be recovered among survivors of a selection, can be inferred from the footprint. Thus, one can determine phenotypes of nonviable mutants, which would be difficult to study using conventional methods.

While we have chosen to carry out initial development of this technique using a target gene encoding an RNA molecule, an identical procedure could be used to identify functional features in a protein. In mutagenizing genes that code for proteins, the insertion or deletion generally would be a multiple of three bases to maintain reading frame. Almost any sequence, except a sequence that is already present in the gene, can be introduced as an insertional mutation in this procedure. For example, the sequence could (in one of the reading frames) encode a peptide that tends to destabilize a particular secondary structure. It could code for amino acids with bulky side chains that might disrupt closely packed domains in a protein’s hydrophobic core. It could be a (His) sequence to aid protein purification, or an epitope tag to facilitate subcellular localization or purification of the protein. It could incorporate a peptide that confers a new functionality to the protein—e.g., the ability to be phosphorylated by a specific protein kinase, cut by a specific endoprotease, glycosylated, or transported to a specific cellular compartment. We anticipate that it often will be useful to conduct several footprinting analyses of the same gene, each using a different sequence for the inserted oligonucleotide, because one sequence might be tolerated at a particular location while a second sequence with different properties might not.

Genetic footprinting allows considerable variation in the size of the insertion. The ability to make a diverse set of large insertions might be particularly useful for protein engineering where large insertions and deletions offer more effective means to alter protein structure and function than multiple substitution mutations (18). The minimum practical size for the inserted sequence depends upon the method chosen for mutant analysis. A PCR-based method, like that used in our initial analysis, requires that the insert be long enough to serve as a specific PCR primer. The insert could be as short as four to eight bases if it were to include a restriction endonuclease site, allowing analysis as described for substitution mutations.

Genetic footprinting relies on mutations at diverse sites in a gene. Retroviral integrases are well suited for making such insertions, because they display little target specificity for naked DNA. The dense pattern of bands seen in the analysis of unselected pool of mutants indicated that integration of the VE oligonucleotide was sufficiently random that insertions at almost every internucleotide position in the plasmid were represented in the sample. However, the frequency of integration varied among the different sites, resulting in variable intensity of the corresponding bands. We found that the most favored integration sites in πAN13 were preferred 20- to 50-fold over the least-favored ones, for reasons that are not yet well understood (6). Therefore, a library whose size is 50 times greater than the number of base pairs in the mutagenized gene has a reasonable chance of containing a mutation at any given internucleotide position. Different retroviral integrases and transposases favor different sites for integration (6). Thus, if a region of the gene happened to be a particularly poor target for integration mediated by MoMLV integrase, other integrases or bacterial transposases, such as the MuA transposase, could be used for the mutagenesis.

Genetic footprinting most easily can be applied to situations where growth, survival, or replication under some condition can be used as a selection for gene function, but its use is not restricted to these situations. Indeed, any selection that makes recovery of a DNA molecule dependent on a property of the DNA sequence or its encoded products is amenable to genetic footprinting. Thus, this technique should allow rapid and efficient investigation of the essential features of many cloned genes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Brian Scottoline for generously supplying MoMLV integrase; Jennifer Gerton for preliminary experiments in initial development of method; Duane Grandgenett for communicating unpublished data that identified optimum reaction conditions for concerted integration using avian myeloblastosis virus integrase; and Karl Reich for PCR primers that allowed amplification of the chloramphenicol-resistance gene. This investigation was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and by grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (Grant UO1 AI27205) and The Jane Coffin Childs Memorial Fund for Medical Research. I.R.S. is a fellow of The Jane Coffin Childs Memorial Fund for Medical Research. R.A.C. has been supported by a National Science Foundation fellowship and by Cancer Biology Training Grant 5T32CA09302. P.O.B. is an Assistant Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: VE, viral end; MoMLV, Moloney murine leukemia virus.

References

- 1.Huang H V, Little P F, Seed B. Bio/Technology. 1988;10:269–283. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-409-90042-2.50020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang A C Y, Cohen S N. J Bacteriol. 1978;134:1141–1156. doi: 10.1128/jb.134.3.1141-1156.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dotan I, Scottoline B, Heuer T, Brown P. J Virol. 1995;69:456–468. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.1.456-468.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Craigie R, Fujiwara T, Bushman F. Cell. 1990;62:829–837. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90126-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jonsson C B, Donzella G A, Roth M J. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:1462–1469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pryciak P M, Varmus H E. Cell. 1992;69:769–780. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90289-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dirheimer G, Keith G, Dumas P, Westhof E. In: tRNA Structure, Biosynthesis and Function. Söll D, RajBhandary U L, editors. Washington, DC: Am. Soc. Microbiol.; 1995. pp. 93–126. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Apirion D, Miczak A. BioEssays. 1993;15:113–120. doi: 10.1002/bies.950150207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bedouelle H. Biochimie. 1990;72:589–598. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(90)90122-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kraemer K H, Seidman M M. Mutat Res. 1989;220:61–72. doi: 10.1016/0165-1110(89)90011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deutscher M P. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1990;39:209–240. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60628-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sprinzl, M., Hartmann, T., Weber, J., Blank, J. & Zeidler, R. (1989) Nucleic Acids Res. 17, Suppl. 1–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Brown P O, Bowerman B, Varmus H E, Bishop J M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:2525–2529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.8.2525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vora A C, Grandgenett D. J Virol. 1995;69:7483–7488. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.7483-7488.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goodarzi G, Im G-J, Brackmann K, Grandgenett D. J Virol. 1995;69:6090–6097. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.10.6090-6097.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith V, Botstein D, Brown P O. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6479–6483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith V, Chou K, Lashkari D, Botstein D, Brown P O. Science. 1996;274:2069–2074. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5295.2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shortle D, Sondek K. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1995;6:387–393. doi: 10.1016/0958-1669(95)80067-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]