Abstract

β-Adrenergic receptor (βAR) downregulation and desensitization are hallmarks of the failing heart. However, whether abnormalities in βAR function are mechanistically linked to the cause of heart failure is not known. We hypothesized that downregulation of cardiac βARs can be prevented through inhibition of PI3K activity within the receptor complex, because PI3K is necessary for βAR internalization. Here we show that in genetically modified mice, disrupting the recruitment of PI3K to agonist-activated βARs in vivo prevents receptor downregulation in response to chronic catecholamine administration and ameliorates the development of heart failure with pressure overload. Disruption of PI3K/βAR colocalization is required to preserve βAR signaling, since deletion of a single PI3K isoform (PI3Kγ knockout) is insufficient to prevent the recruitment of other PI3K isoforms and subsequent βAR downregulation with catecholamine stress. These data demonstrate a specific role for receptor-localized PI3K in the regulation of βAR turnover and show that abnormalities in βAR function are associated with the development of heart failure. Thus, a strategy that blocks the membrane translocation of PI3K and leads to the inhibition of βAR-localized PI3K activity represents a novel therapeutic approach to restore normal βAR signaling and preserve cardiac function in the pressure overloaded failing heart.

Introduction

Heart failure is a syndrome characterized by depressed ventricular function, fluid retention, and increased mortality (1). Classic characteristics of the failing heart include a reduction in β-adrenergic receptor (βAR) number and diminished contractile response to catecholamine stimulation, due in part to activation of the sympathetic nervous system (2, 3). Treatment of heart failure patients with beta-blockers may reverse this process, and recent clinical and experimental data support the concept that normalizing βAR function can lead to improved cardiac function and prolonged survival (4–6). Despite these newer therapies, however, the mortality rate for patients with chronic heart failure remains high, indicating a need for novel strategies that are synergistic with current treatments.

βARs belong to the large family of G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) that relay their signals by coupling to G proteins and activating or inhibiting different effector molecules, such as an enzyme or ion channel (3, 7). Under conditions of heart failure there is a downregulation in the number of βARs and diminished contractile response to catecholamine stimulation, due in part to activation of the sympathetic nervous system (2, 3). Upon catecholamine binding to βARs, the heterotrimeric G proteins dissociate into Gα and Gβγ subunits. The Gα subunit is free to activate the effector adenylyl cyclase to generate the second messenger cAMP and lead to an increase in heart rate and contractility. The termination of GPCR signals is initiated by phosphorylation of the agonist-occupied receptor primarily by the G protein–coupled receptor kinase (commonly known as βARK1), followed by the binding of arrestin proteins. Receptor phosphorylation and arrestin binding not only act to sterically inhibit further G protein activation, but is also the first step in the process of receptor internalization and downregulation (7), a process that we have shown to require the presence of PI3K within the agonist-occupied receptor complex (8).

PI3Ks are a conserved family of enzymes that catalyze the generation of D-3 phosphatidylinositols (PtdIns), which in turn regulate diverse cellular processes such as cell survival and proliferation, cytoskeletal arrangements, receptor endocytosis, and cardiac contractility (9–11). Based on their structure and substrate specificity, PI3Ks can be divided into three classes (I, II, and III). The class I PI3Ks can be further subdivided into class IA (activated by receptor tyrosine kinases, PI3Kα) and IB (activated by Gβγ subunits of heterotrimeric G proteins, PI3Kγ). Recent studies have demonstrated important roles for both PI3Kα and PI3Kγ in cardiac growth and function (9, 12, 13). For instance, PI3Kγ is upregulated in response to in vivo pressure-overload hypertrophy in the heart (14), and the absence or inhibition of PI3Kγ leads to enhanced cardiac contractility (9, 12). Moreover, overexpression of PI3Kα mutants in hearts of transgenic mice leads to changes in the size of cardiomyocytes, indicating this isoform may be important for cell growth in the heart (13). Whether PI3K plays a role in the development of heart failure through its interaction with βARs is unknown.

PI3K binds to βARK1 through a helical domain known as the phosphoinositide kinase domain (PIK), which is conserved among all PI3K isoforms. Upon agonist stimulation, βARK1 mediates the translocation of PI3K to βARs, allowing for the generation of phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-tri-phosphate (PtdIns-3,4,5-P3) (8, 10). The local generation of PtdIns-3,4,5-P3 within the receptor complex functions to enhance the recruitment of a number of phosphoinositide-binding endocytic proteins such as β-arrestin and AP-2, essential for βAR internalization (8, 15). Furthermore, in cell culture systems, overexpression of a catalytically inactive PI3K or PIK domain that disrupts the interaction between PI3K and βARK1 by displacing both class IA and IB isoforms blocks agonist-stimulated βAR internalization (8, 10).

Since βARK1-mediated localization of PI3K is required for internalization of βARs, we postulated that under conditions of excess catecholamines, similar to that found in chronic human heart failure, PI3K would play an important role in the chronic downregulation of βARs. To test the hypothesis that βAR downregulation and cardiac dysfunction could be prevented in vivo by blocking the βARK1-mediated recruitment of active PI3K, we studied mice with cardiac-specific overexpression of a catalytically inactive mutant of PI3Kγ (PI3Kγinact) and PI3Kγ knockout mice (PI3Kγ-KO) following exposure to chronic catecholamine administration or pressure overload–induced heart failure.

Methods

Generation of transgenic mice.

The pCMV-PI3Kp110γ-hemagglutinin (pCMV-PI3Kp110γ-HA) mutant (PI3Kγinact) (Δ942-981, a deletion in the ATP-binding site) was a generous gift from Charles S. Abrams (Department of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania Medical School, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA)(16). The cDNA insert of PI3Kγinact was amplified using a Pfu platinum turbo Taq high-fidelity enzyme (Stratagene, La Jolla, California, USA) with a 5′ primer (5′-TGCGGATCCGCCACCATGGAGCTGGAGAACTATAAACAG-3′) containing ClaI for subcloning, followed by Kozak consensus sequence and 3′-primer (5′-ACCCGGGATCCTTAAGCGTAGTCTGGTACGT-3′) with a ClaI site for subcloning. The PCR product was subcloned directly into a vector downstream of the αMyHC gene promoter and upstream of an HA epitope and an SV40 polyadenylation site. The subcloned cDNA was sequenced and digested with restriction enzymes XhoI and NotI to check for orientation. Transgenic founders were identified by Southern blot analysis of tail DNA using the SV40 poly(A) as a probe. Transgenic founder mice were backcrossed into both DBA and C57BL/6 backgrounds for nine generations. The DBA background PI3Kγinact transgenic mice was used for the osmotic pump study while C57BL/6 was used in the transverse aortic constriction (TAC) studies. The PI3Kγ knockout mice were a generous gift from Dianquing Wu (University of Connecticut Health Center), and their method of generation has been published previously (17). The background of the PI3Kγ knockout mice was 129/B6, and 129/B6 mice were used as controls. Animals were handled according to the approved protocols and animal welfare regulations of the Institutional Review Board at Duke University Medical Center.

Echocardiography.

Echocardiography was performed on conscious mice at 3–4 months of age with an HDI 5000 echocardiograph (ATL, Bothell, Washington, USA) as described previously (18).

Mini-osmotic pump implantation.

Mini-osmotic pumps were implanted as described previously (19). Isoproterenol was dissolved in 0.002% ascorbic acid, and pumps (Alzet model 1007D; DURECT Corp., Cupertino, California, USA) were filled to deliver at a rate of 3 mg/kg/d over a period of 7 days. In control mice pumps that delivered vehicle (0.002% ascorbic acid) were implanted.

In vivo pressure overload.

Mice were anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (2.5 mg/kg), and TAC was performed as described previously (18). Twelve weeks after surgery, the trans-stenotic pressure gradient was assessed by recording simultaneous measurement of right carotid and left axillary arterial pressures.

Hemodynamic evaluation in mice.

Hemodynamic evaluation was performed as described previously (20). Hemodynamic measurements were recorded at baseline and 45 seconds after infusion of incremental doses of isoproterenol (50, 500, and 1,000 pg). Hemodynamic measurements were analyzed by SONOVIEW software (Sonometrics Corp., London, Ontario, Canada).

Membrane fractionation, lipid kinase assay, βAR radioligand binding and adenylyl cyclase activity.

Total PI3K and PI3Kγ assays from the left ventricles (LV) flash-frozen in liquid N2 were carried out as described previously (10). Membrane fractions were prepared as described previously (18). For the βARK1-associated PI3K assay, 500 μg of membrane fraction was used for immunoprecipitation with the C5/1 mAb directed against βARK1 (10). To directly measure the generation of PtdIns-3,4,5-tri-phosphate (PIP3), in vitro lipid kinase assays were performed using the substrate PtdIns-4,5-P2, which can be used by class I PI3Ks to generate PtdIns-3,4,5-P3. The lipids were extracted with chloroform/methanol (ratio of 1:1), and organic phase was spotted on TLC plates and resolved chromatographically with 2N glacial acetic acid/1-propanol (ratio of 35:65). Dried plates were exposed, and autoradiographic signals were quantitated using Bio-Rad Phosphorimager. Receptor binding with 25 μg of the membrane fraction was performed as described previously (18) using βAR ligand ([125I] cyanopindolol, 250 pM). All assays were performed in triplicate, and receptor density (in femtomoles) was normalized to milligrams of membrane protein. Adenylyl cyclase assays were performed as described previously (18) using 20 μg of the membrane fraction. Generated cAMP was quantified using a liquid scintillation counter (MINAXIβ-4000).

βARK1 activity by rhodopsin phosphorylation.

Membrane (50 μg) and cytosolic fraction (150 μg) were incubated with rhodopsin-enriched rod outer segments with 10 mM MgCl2 and 100 μM ATP containing [γ-32P] ATP. The reactions were incubated in white light for 15 minutes, stopped, resolved by SDS-PAGE gel, and autoradiography was carried out as described previously (18).

Immunoblotting.

Immunoblotting was done as described previously (18). Immunoprecipitating Ab’s were added to 500 μg of membrane fraction. Ab’s to phospho-protein kinase B (pPKB) and phospho-glycogen synthase kinase (pGSK) were used for blotting at 1:1,000, anti-hemagglutinin (PI3Kγinact-HA) at 1:500, and 1:10,000 for βARK1. Detection was carried out using ECL (Amersham Biosciences Corp., Piscataway, New Jersey, USA), and bands were quantified with densitometry.

MAPK.

MAPK activities were assessed from clarified LV extracts as the capacity of immunoprecipitated extracellular signal-regulated kinase-p42/extracellular signal-regulated kinase-44 (ERK-p42/ERK-p44), p38, p38β, and JNK-p46/JNK3 MAPK to phosphorylate in vitro substrates (myelin basic protein or GST-JUN) as described previously (18).

Survival studies.

Survival data were analyzed by using a Kaplan-Meier survival analysis with a log-rank method of statistics. Survival analysis excluded mice that died within 3 days after surgery (TAC) and mice that had a pressure gradient of less that 15 mmHg for both WT and PI3Kγinact mice.

Statistical analysis.

Data are expressed as mean plus or minus SEM. Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA was used to evaluate hemodynamic measurement under basal and isoproterenol treatment and for analysis of cardiac function after TAC. Post-hoc analysis was performed with a Scheffé test. Two-sample comparisons were performed with Student’s t tests. The Student’s t test with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was used to evaluate data from the isoproterenol time course. For all analysis, a value of P less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

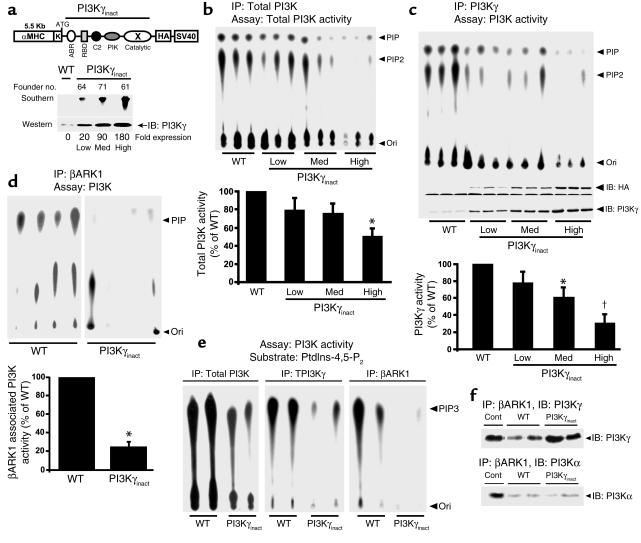

Mice overexpressing PI3Kγinact have decreased basal PI3K and βARK1-associated PI3K activity.

We generated PI3Kγinact mice by subcloning PI3Kγinact downstream of the αMHC promoter (Figure 1a, upper panel), which is expressed in cardiomyocytes (21). Three founders (numbers 64, 71, and 61) were generated, characterized by 20-, 90- and 180-fold overexpression of the mutant protein relative to WT (Figure 1a, lower panel). Robust total PI3K activity in WT mice was observed without a significant reduction in activity among the 20- and 90-fold overexpressing PI3Kγinact transgenic mice. The 180-fold overexpressing PI3Kγinact mice showed a 45% reduction in total PI3K compared with the WT (Figure 1b). Assays specific for the PI3Kγ isoform showed 40% and 65% reductions in PI3Kγ activity in the hearts from the 90- and 180-fold overexpressing transgenic mice, respectively (Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

Generation of transgenic mice with decreased cardiac βAR-localized PI3K activity. (a) Diagram of the transgene construct containing the PI3Kγinact cDNA (upper panel). Southern (10 μg of DNA) and Western blots (100 μg of cytosolic extract) from WT and three transgenic founder lines using SV-40 probe and anti-PI3Kγ Ab, respectively (lower panel). (b and c) Basal levels of total PI3K (b) and PI3Kγ (c) activity in the LV relative to WT (n = 9, WT and transgenic lines); 2 mg of cytosolic extract was used for immunoprecipitation with PI3K Ab. *P < 0.05 versus WT; †P < 0.01 versus WT. (d) Basal βARK1-associated PI3K activity in the LV of WT (n = 6) and 180-fold overexpressing transgenic mice (n = 6); 4 mg of cytosolic extract was used for immunoprecipitation with βARK1 mAb. (e) Total PI3K, PI3Kγ, and βARK1-associated PI3K activity in the left LVs measured by their ability to phosphorylate PtdIns-4,5-P2 to PtdIns-3,4,5-P3. (f) Immunoblotting for PI3Kα or PI3Kγ following immunoprecipitation with βARK1 mAb from clarified myocardial lysates (3 mg). *P < 0.001 versus WT. IP, immunoprecipitation; αMHC, alpha myosin heavy chain promoter; K, Kozak sequence; C2, similar to type II C2 domain found in phospholipase Cδ1; X, catalytically inactive; ABR, adaptor binding region; RBD, ras-binding domain; HA, hemagglutinin epitope tag; PIP, phosphatidylinositol mono-phosphate; PIP2, phosphatidylinositol bis-phosphate; Ori, origin; Cont (plus control), immunoprecipitation of PI3Kα or PI3Kγ with its respective Ab and immunoblotted for PI3Kα or PI3Kγ; βARK, β-adrenergic receptor kinase.

Since we have previously shown a direct interaction between βARK1 and PI3K (8, 10), we used the 180-fold overexpressing mice to determine whether the PI3Kγinact transgenic mice had decreased βARK1-associated PI3K activity by immunoprecipitating βARK1 from left ventricular lysates and assaying for PI3K activity. Importantly, there was a marked reduction in βARK1-associated PI3K activity in PI3Kγinact hearts compared with WT (Figure 1d). We next tested the ability of WT and PI3Kγinact transgenic mice (180–fold) to generate PIP3, the physiologically relevant phospholipid, using the specific class I PI3K substrate PtdIns-4,5-P2. Robust total PI3K and PI3Kγ activity was observed in the WT mice, while generation of PIP3 was attenuated in the PI3Kγinact transgenic mice (Figure 1e). Importantly, reduced generation of PIP3 was also observed when βARK1 was immunoprecipitated and assayed for PI3K activity in the PI3Kγinact mice (Figure 1e). To directly assess the association of PI3K with βARK1 in the heart, βARK1 was immunoprecipitated from myocardial lysates and blotted for the coimmunoprecipitating PI3K isoform. PI3Kγ interacts with βARK1 in the WT mice, and this interaction is increased in the PI3Kγinact transgenic mice due to its association with the overexpressed PI3Kγinact transgene (Figure 1f). In contrast, low levels of PI3Kα are found associated with βARK1 in the heart (Figure 1f). Taken together, these data indicate that overexpression of a catalytically inactive PI3Kγ successfully displaces endogenous active PI3K from βARK1, while having only a modest effect on total cellular PI3K activity.

To determine whether reduced βARK1-associated PI3Kγ activity would alter the physiologic phenotype of the transgenic mice under basal conditions, we assessed cardiac function by echocardiography and cardiac catheterization. No differences were found between WT and any of the PI3Kγinact lines for LV chamber dimensions, fractional shortening, heart rate, or in the LV weight/body weight (LVW/BW)ratios. Furthermore, cardiac catheterization of the WT and 180-fold overexpressing transgenic mice revealed no differences in contractile function (LV dP/dtmax) or other hemodynamic parameters (Table 1). These data suggest that although a high level of PI3Kγinact overexpression leads to a significant reduction in βARK1-associated PI3K activity, it does not result in any physiologic, morphometric, or hemodynamic changes under unstressed basal conditions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Physiologic parameters in WT and PI3Kγinact (TG) lines

PI3Kγinact overexpression prevents isoproterenol-induced βAR desensitization and downregulation in vivo.

Since we have previously shown a role for PI3K in βAR internalization in vitro, we tested the hypothesis that overexpression of PI3Kγinact would prevent βAR downregulation in vivo following chronic exposure to high levels of catecholamines. Transgenic mice overexpressing PI3Kγinact (180–fold) and their WT littermates were chronically treated with the catecholamine isoproterenol (ISO), for 7 days by osmotic mini-pumps to induce βAR downregulation. We then determined βAR responsiveness to additional ISO in intact catheterized mice by measuring the first derivative of LV pressure rise, LV dP/dt in individual mice. Compared with treatment with vehicle, chronic ISO treatment resulted in a substantial loss of catecholamine responsiveness in WT mice (Figure 2a). In marked contrast, treated PI3Kγinact mice showed normal contractile responses to catecholamines, indicating normal βAR sensitivity. Chronic ISO treatment resulted in a similar 20% increase in the LVW/BW ratios of both WT and transgenic mice (WT: vehicle 3.5 ± 0.1 mg/g, ISO 4.3 ± 0.1 mg/g; PI3Kγinact: vehicle 3.4 ± 0.1 mg/g, ISO 4.1 ± 0.1 mg/g, P = NS). Thus, overexpression of PI3Kγinact in the heart preserves βAR sensitivity under conditions of excess catecholamine levels, without affecting growth responses.

Figure 2.

PI3Kγinact-overexpressing mice do not undergo βAR desensitization or downregulation under conditions of chronic catecholamine administration. (a) In vivo hemodynamic studies showing βAR responsiveness as monitored by the increase in left ventricular contractility (LV dP/dtmax) in WT and PI3Kγinact mice following 7 days of ISO (closed circles: n = 9; closed squares: n = 7) or vehicle (open circles: n = 13; open squares: n = 8) treatment. *P < 0.0001 (two-way ANOVA) WT ISO versus PI3Kγinact ISO. (b) βARK1-associated PI3K activity in WT and PI3Kγinact ventricles (500 μg of membrane fraction) following 7 days of ISO (n = 6) or vehicle treatment (n = 5–6). Values are expressed relative to vehicle-treated WT. Immunoblotting the HA-epitope tag (PI3Kγinact) following immunoprecipitation with βARK1 from 500 μg of membrane fraction (upper immunoblot, IB: HA). *P < 0.001 ISO 7 days versus vehicle. (c) In vitro myocardial βARK1 activity measured by rhodopsin (Rho) phosphorylation in WT and PI3Kγinact mice following 7 days of ISO or vehicle treatment. (d) βAR density among WT and PI3Kγinact mice following 7 days of ISO administration (n = 6) or vehicle treatment (n = 5–6). *P < 0.05 ISO 7 days versus vehicle. (e) Basal (white bars) and in vitro ISO-stimulated (black bars) adenylyl cyclase activity in WT and PI3Kγinact mice following 7 days of ISO (n = 6) or vehicle treatment (n = 5–6). Adenylyl cyclase activity upon NaF stimulation: 257 ± 21 pmol/mg/min and 244 ± 18 pmol/mg/min for vehicle and ISO 7-day treatment, respectively, in WT; 242 ± 12 pmol/mg/min and 239 ± 24 pmol/mg/min for vehicle and ISO 7-day treatment, respectively, in PI3Kγinact mice. *P < 0.002 ISO versus basal. βARK1 (C5/1) mAb is directed against the catalytic site of βARK1 blocking its enzymatic activity.

To determine whether chronic ISO administration reduces βARK1-associated PI3K activity in myocardial membranes, WT and PI3Kγinact mice were treated with ISO for 7 days. A robust, 2.6-fold increase in βARK1-associated PI3K activity was observed in WT mice following chronic ISO treatment (Figure 2b). This effect was completely abolished in the transgenic mice overexpressing PI3Kγinact (Figure 2b), despite the fact that PI3Kγinact protein was recruited to the plasma membrane (Figure 2b; immunoblotting [IB]: HA). Cytosolic βARK1 expression was also increased with chronic ISO treatment in the hearts of both WT and PI3Kγinact mice hearts (data not shown). Therefore, overexpression of PI3Kγinact displaces active endogenous PI3K from βARK1, leading to the translocation of inactive PI3K by βARK1 to the myocardial membrane under conditions of agonist stimulation.

Translocation of βARK1 depends on dissociated Gβγ subunits from heterotrimeric G proteins (22). Since PI3Kγ binds Gβγ subunits, we tested whether overexpression of PI3Kγinact alters the membrane recruitment of βARK1. Membrane and cytosolic extracts from WT and PI3Kinact transgenic hearts were measured for their capacity to phosphorylate the GPCR rhodopsin. Membrane extracts from chronic ISO-treated hearts showed a similar increase in βARK1 activity (Figure 2c) that was abolished by preincubation with βARK1 mAb (anti–βARK1/βARK2-C5/1) (Figure 2c) (23). These data demonstrate that overexpression of PI3Kγinact does not alter the function or recruitment of βARK1 to myocardial membranes.

To determine whether inhibition of locally generated PtdIns-3,4,5-P3 within the plasma membrane diminishes the degree of βAR downregulation and desensitization that occurs with chronic ISO treatment, we measured βAR density and adenylyl cyclase activity in crude myocardial membrane preparations from WT and transgenic mouse hearts after 7 days of chronic ISO treatment. βAR density was reduced 33% in chronic ISO-treated WT hearts compared with vehicle-treated WT hearts (Figure 2d). In contrast, no significant decrease in βAR density occurred in the ISO-treated PI3Kγinact hearts compared with vehicle-treated PI3Kγinact hearts (Figure 2d). Furthermore, overexpression of PI3Kγinact completely preserved adenylyl cyclase activity following chronic ISO treatment compared with WT (Figure 2e). Taken together, these data show that under conditions of high levels of circulating catecholamines, overexpression of PI3Kγinact in the heart preserves in vivo βAR responsiveness by preventing the downregulation and desensitization of myocardial βARs.

To determine the time course of βARK1-mediated PI3K recruitment, receptor desensitization, and downregulation, WT and PI3Kγinact transgenic mice were treated with isoproterenol by mini-osmotic pump for 12 hours, 24 hours, 3 days, and 5 days. Significant βARK1-associated PI3K activity was observed in membrane fractions of WT mice within 12 hours of ISO and was sustained throughout the entire time course of ISO administration (Figure 3a). In contrast, βARK1-mediated PI3K recruitment was prevented in the PI3Kγinact transgenic mice over the same time period (Figure 3a). Vehicle treatment had no effect on the recruitment of PI3K (Figure 3a and Figure 2b). βAR receptor desensitization as measured by diminished ISO-stimulated membrane adenylyl cyclase activity also occurred within 12 hours of ISO administration (Figure 3b), which was also prevented in the PI3Kγinact transgenic mice (Figure 3b). As opposed to the early events of PI3K recruitment and βAR desensitization, downregulation of βARs did not occur until 3 days of ISO administration and was significantly reduced 30% upon 5 days of chronic catecholamine administration (Figure 3c). Importantly, no significant changes in βAR density occurred in the PI3Kγinact transgenic mice throughout the entire ISO administration time course (Figure 3c).

Figure 3.

βARK1-mediated PI3K recruitment leads to desensitization and downregulation of βARs. (a) βARK1-associated PI3K activity in WT and PI3Kγinact ventricles (500 μg of membrane fraction) following 12 hours, 24 hours, 3 days, and 5 days of ISO administration. (b) In vitro ISO-stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity represented as the fold increase over basal level in WT (white bars) and PI3Kγinact (black bars) mice following 12 hours, 24 hours, 3 days, and 5 days of chronic ISO administration. (c) βAR density among WT and PI3Kγinact mice following 12 hours, 24 hours, 3 days, and 5 days of ISO infusion. (d) βARK1-associated PI3K activity measured by the ability to in vitro phosphorylate PtdIns-4,5-P2 as a substrate to generate PtdIns-3,4,5-P3 in WT and PI3Kγinact ventricles (500 μg of membrane fraction) following 5 days of ISO administration. *P < 0.05 WT ISO treated versus WT vehicle. †P < 0.05 WT ISO versus PI3Kγinact ISO at same time point. Sub, substrate.

The ability of βARK1-associated PI3K to generate PIP3 was measured using the in vitro substrate PtdIns-4,5-P2 from the membranes of 5-day ISO-treated WT and PI3Kγinact mice. Robust PIP3 production was observed with the βARK1 immunoprecipitates from the WT mice, which was completely blocked in the PI3Kγinact transgenic mice (Figure 3d). These data show that overexpression of PI3Kγinact transgene displaces endogenous PI3K from βARK1 and that βARK1-mediated recruitment of PI3K and receptor desensitization occurs early with agonist stimulation followed by receptor downregulation.

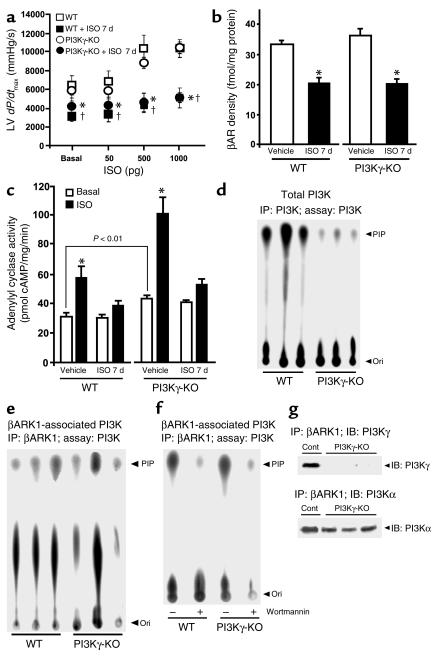

PI3Kγinact overexpression displaces all endogenous interacting PI3K isoforms from βARK1.

An important issue is whether the preservation of βAR functions with chronic ISO in the transgenic mice occurred because of the displacement of endogenous PI3K from the βARK1/PI3K complex, as we postulate, or due to a generalized reduction in cellular PI3Kγ activity. To test the latter possibility, we used PI3Kγ knockout (PI3Kγ-KO) mice that were homozygous for the PI3Kγ null allele. Mini-osmotic pumps containing ISO or vehicle were implanted in both WT and PI3Kγ-KΟ mice and hemodynamic studies performed 7 days later. ISO induced a brisk increase in LV dP/dtmax in both the vehicle-treated WT and PI3Kγ-KO mice (Figure 4a), whereas in vivo βAR responsiveness was severely attenuated in chronically ISO-treated PI3Kγ-KO and WT mice. The difference in basal LV dP/dtmax for WT control of PI3Kγ-KO mice and WT controls of PI3Kγinact transgenic mice is likely attributed to the different genetic backgrounds of these mice and is consistent with our previous studies (24, 25). Importantly, a similar response to ISO is observed for the two inbred WT strains with a twofold increase in LV dP/dtmax at maximal doses of ISO.

Figure 4.

Preservation of βAR sensitivity in PI3Kγinact mice is due to the displacement of PI3K from βARK1. (a) In vivo hemodynamic studies of βAR responsiveness (increase in LV dP/dtmax) following 7 days of ISO (closed circles: n = 7; closed squares: n = 7) or vehicle (open circles: n = 5; open squares: n = 5) treatment. *P < 0.0001 (ANOVA) PI3Kγ-KO ISO 7 days versus PI3Kγ-KO vehicle. †P < 0.0001 WT ISO 7 days versus WT vehicle. (b) βAR density following 7 days of ISO (n = 6) or vehicle (n = 4) treatment. *P < 0.001 ISO versus vehicle. (c) Basal (white bars) and in vitro ISO-stimulated (black bars) adenylyl cyclase activity following 7 days of ISO (n = 6–8) or vehicle treatment (n = 8). Adenylyl cyclase activity upon NaF stimulation: 179.0 ± 5.7 pmol/mg/min and 149.9 ± 4.8 pmol/mg/min for vehicle and ISO, respectively, for 7 days of treatment in WT; 325.2 ± 7.5 pmol/mg/min and 230.3 ± 5.6 pmol/mg/min for vehicle and ISO, respectively, for 7 days treatment in PI3Kγ-KO mice. *P < 0.001 ISO versus basal. (d) Total PI3K activity in WT (n = 6) and PI3Kγ-KO mice (n = 6). (e) βARK1-associated PI3K activity from LV extracts of WT (n = 6) and PI3Kγ-KO (n = 6) mice. (f) βARK1-associated PI3K activity in the presence of wortmannin, a selective PI3K inhibitor. (g) Immunoblotting for PI3Kγ and PI3Kα following immunoprecipitation with βARK1. Cont (plus control), immunoprecipitation of PI3Kα or PI3Kγ with its respective Ab and immunoblotted for PI3Kα or PI3Kγ.

We further evaluated βAR density and adenylyl cyclase activity in crude myocardial membrane preparations from WT and PI3Kγ-KO mice, and βAR density was equally reduced approximately 40% in chronic ISO-treated WT and PI3Kγ-KO hearts (Figure 4b) compared with the vehicle-treated hearts. Despite the increase in basal adenylyl cyclase activity in the PI3Kγ-KO mice (Figure 4c), as previously described (9), chronic ISO treatment resulted in marked desensitization to an extent similar to the WT mice (Figure 4c). Taken together, these data show that under conditions of high levels of circulating catecholamines absence of PI3Kγ does not prevent βAR downregulation or receptor desensitization, in marked contrast to the results obtained in the PI3Kγinact transgenic mice.

The above PI3Kγ-KO studies suggest that βARK1 may be interacting with other PI3K isoforms to promote βAR internalization, a finding we have shown previously in vitro for PI3Kα (10). To demonstrate that βARK1 interacts with other PI3K isoforms in the heart, total and βARK1-associated PI3K activity was measured from the myocardial lysates of WT and PI3Kγ-KO mice. PI3Kγ activity was not detectable in the knockout mice, confirming the null phenotype (data not shown), while total PI3K activity was markedly reduced (Figure 4d). We found the level of βARK1-associated PI3K activity in the hearts of PI3Kγ-KO mice, however, to be identical to that of the WT hearts (Figure 4, e and f), however, and this lipid kinase activity was wortmannin sensitive (Figure 4f). To test directly for the interacting PI3K isoform with βARK1 in the PI3Kγ-KO mice, βARK1 was immunoprecipitated from clarified myocardial lysates and blotted for both PI3Kα and PI3Kγ. As shown in Figure 4g, PI3Kα is the only isoform that coimmunoprecipitates with βARK1 in the PI3Kγ-KO mice. Taken together, these data show that interrupting the βARK1/PI3K interaction in the heart in vivo preserves βAR function in response to chronically elevated levels of circulating catecholamines. These data also show that in the absence of PI3Kγ, βARK1 can interact with other PI3K isoform(s) in vivo to promote downregulation and desensitization of βARs.

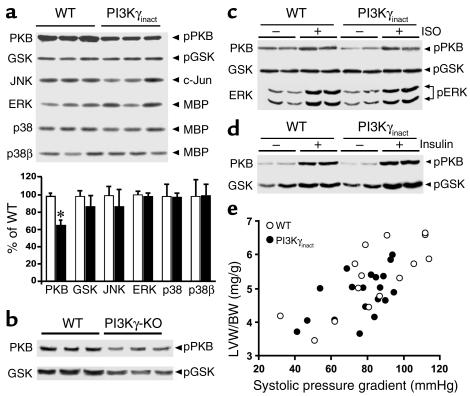

Cardiac-specific overexpression of PI3Kγinact does not alter downstream PI3K signaling or development of cardiac hypertrophy.

Since PI3K plays an important role in regulating cellular signaling, we wanted to exclude the possibility that overexpression of PI3Kγinact altered the activity of downstream signaling pathways. Under unstimulated conditions, no difference in activity was observed for all the three major MAPK pathways (ERK, JNK, and p38/p38β) between the PI3Kγinact mice and their WT littermate controls (Figure 5a). While PI3Kγinact mice showed a significant decrease in pPKB, this decrease did not change the phosphorylation status of the immediate downstream enzyme glycogen synthase kinase (GSK3) (Figure 5a). In contrast to the findings in the PI3Kγinact mice, both pPKB and pGSK were reduced in the PI3Kγ-KO mice in the unstressed basal state (Figure 5b). We further determined whether overexpression of PI3Kγinact transgene in the mice would affect immediate downstream signaling molecules like PKB, GSK3, and ERK following either GPCR or growth factor stimulation. Chronic ISO administration for 7 days showed a similar increase in both pPKB and pERK in the PI3Kγinact mice compared with the WT and had no effect on the level of pGSK3 (Figure 5c). Moreover, acute insulin administration led to significant increase of pPKB and pGSK levels in the PI3Kγinact transgenic mice, also similar to the increase observed in the hearts of WT mice (Figure 5d). These studies, taken together, show that overexpression of PI3Kγinact transgene does not interfere with the downstream signaling of GPCR or receptor tyrosine kinases.

Figure 5.

Cardiac-specific overexpression of PI3Kγinact does not alter downstream PI3K signaling. (a) JNK, ERK, p38, and p38β MAPK activities from 1 mg left ventricular myocardial extracts of WT and PI3Kγinact mice under unstimulated conditions. Myocardial extracts (100 μg) from WT and PI3Kγinact mice immunoblotted for pPKB and pGSK. White bars, WT; black bars, PI3Kγinact. *P < 0.01 PI3Kγinact versus WT. (b) Myocardial extracts from WT and PI3Kγ-KO mice immunoblotted for pPKB and pGSK. (c and d) pPKB, pGSK, and phospho-ERK (pERK) immunoblots from 100 μg of myocardial extract of WT and PI3Kγinact mice following 7 days of ISO treatment (c) and upon insulin stimulation (d). (e) Hypertrophic response to pressure overload induced by TAC measured as a ratio of left ventricular weight (LVW/BW) is plotted against the systolic pressure gradient produced by transverse aortic constriction for each WT (open circles: n = 15) and PI3Kγinact (closed circles: n = 19) mouse. Mean pressure gradient between the groups was similar, WT 83.3 ± 6.1 and PI3Kγinact 77.0 ± 3.6 mmHg. JNK, c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; PKB, protein kinase B; GSK, glycogen synthase kinase B; MBP, myelin basic protein.

Since acute agonist stimulation was not altered in PI3Kγinact mice, we wanted to determine whether overexpression of the PI3Kγinact transgene alters the response of the heart to a pleiotropic stimulus such as pressure overload–induced cardiac hypertrophy. The hypertrophic response after 7 days of pressure overload was measured as the index of LVW/BW and plotted against the systolic pressure gradient. Importantly, LVW/BW for individual WT and PI3Kγinact mice across a wide range of systolic pressure gradients was not different, indicating intact hypertrophic signaling pathways in the PI3Kγinact transgenic mice (Figure 5e). As a group there was a similar 150% increase in LV/BW after 7 days of TAC (pre-TAC WT, 3.35 ± 0.52 mg/g, and PI3Kγinact, 3.31 ± 0.46 mg/g, to post-TAC WT, 5.33 ± 1.00 mg/g, and PI3Kγinact, 4.83 ± 0.69 mg/g). Taken together, these data show that overexpression of PI3Kγinact does not inhibit the activation of downstream signaling pathways in the heart in response to multiple extracellular stimuli.

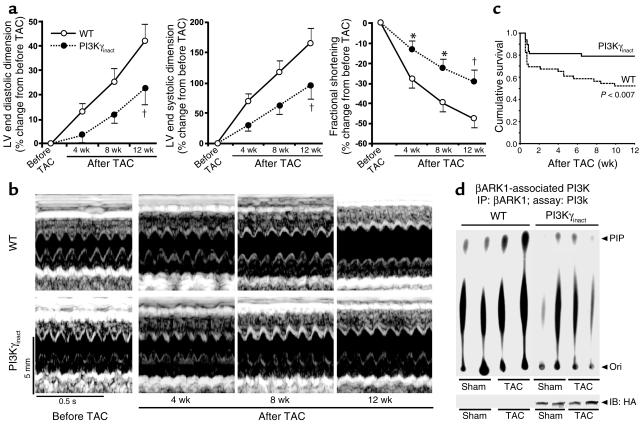

Cardiac-specific overexpression of PI3Kγinact preserves cardiac function under conditions of chronic pressure overload.

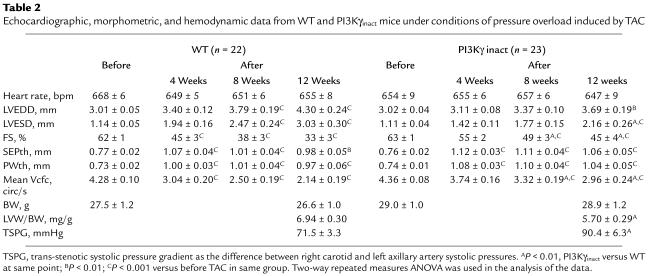

PI3Kγinact mice and their WT littermates underwent TAC and were subsequently followed for 12 weeks. Serial echocardiography showed progressive LV enlargement and deterioration in cardiac function in the WT littermates (Figures 6, a and b) (Table 2). In contrast, PI3Kγinact overexpression significantly delayed the development of cardiac dysfunction and dilatation over the same time period following chronic pressure overload (Figures FIGR RID="F6">, a and b). Furthermore, survival of PI3Kγinact mice after TAC was significantly greater compared with the WT mice (mean survival PI3Kγinact 68 ± 4 days and WT 52 ± 5 days, P < 0.007; Figure 6c), consistent with amelioration of the cardiac phenotype. Transgenic and WT littermate mice used for studies in Table 1 were inbred on a DBA background, while mice used for TAC studies (Table 2) were inbred on a C57BL/6 background. Small differences in basal percentage of fractional shortening between Table 1 and Table 2 are likely attributed to differences in the genetic background.

Figure 6.

PI3Kγinact overexpression delays development of cardiac failure following chronic pressure overload induced by TAC. (a) Percentage of change in LV end diastolic dimension, LV end systolic dimension, and fractional shortening in WT (n = 22) and PI3Kγinact (n = 23) mice measured by serial echocardiography at indicated time intervals after TAC. *P < 0.05 or †P < 0.01 for PI3Kγinact versus WT at the same point. (b) Representative serial echocardiography in conscious WT and PI3Kγinact mice with chronic pressure overload. (c) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis in WT (n = 46) and PI3Kγinact mice (n = 48) after surgery (TAC). P < 0.007, PI3Kγinact TAC versus WT TAC. (d) βARK1-associated PI3K activity in membrane fractions from hearts of WT and PI3Kγinact mice (500 μg) (upper). Immunoblotting for the HA-epitope (PI3Kγinact) following immunoprecipitation with βARK1 (lower).

Table 2.

Echocardiographic, morphometric, and hemodynamic data from WT and PI3Kγinact mice under conditions of pressure overload induced by TAC

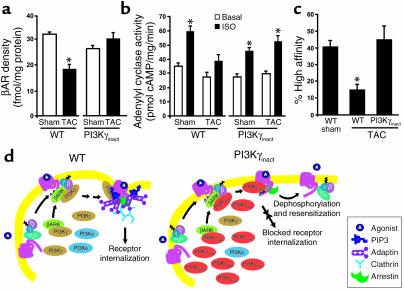

Because PI3Kγ is recruited to the membrane by βARK1, we determined βARK1-associated PI3K activity in the membrane fractions of sham and TAC hearts. The increase in the βARK1-associated PI3K activity in the TAC WT hearts was abolished in the TAC PI3Kγinact mice (Figure 6d) and was replaced by inactive PI3Kγinact protein (Figure 6d; IB: HA). Importantly, blocking the recruitment of active PI3K to the membrane prevented the downregulation of βARs in the cardiac membranes of TAC PI3Kγinact mice in contrast with the TAC WT mice, wherein βARs were significantly reduced (Figure 7a). Since heart failure causes uncoupling of βARs from G proteins, we tested the ability for βARs to activate adenylyl cyclase in pressure-overloaded WT and PI3Kγinact hearts. Importantly, there was complete preservation of adenylyl cyclase activity in PI3Kγinact mice compared with the WT, despite the exposure to chronic pressure overload (Figure 7b). To determine whether the preservation of cyclase activity was the result of enhanced βAR–G protein coupling, competition binding was carried out on membrane fractions from the hearts of WT and PI3Kγinact banded mice. The number of βARs in the high-affinity state was significantly greater in PI3Kγinact hearts compared with WT hearts (P < 0.01) after 12 weeks of TAC and equal to the level in the WT sham (Figure 7c). These data show that βAR density and βAR–Gαs subunit of heterotrimeric G protein effector coupling was preserved in hearts of PI3Kγinact mice despite being subjected to chronic pressure overload, a stimulus that normally induces significant alterations in βAR signaling.

Figure 7.

Competitive displacement of endogenous active PI3K by PI3Kγinact from βARK1 prevents βAR dysfunction following 12 weeks of chronic pressure overload. (a) βAR density among WT and PI3Kγinact mice (WT and PI3Kγinact sham: n = 4; TAC: n = 4). *P < 0.005 WT TAC versus WT sham. (b) Basal (white bars) and ISO-stimulated (black bars) adenylyl cyclase activity in membrane fractions from WT (n = 8–10) and PI3Kγinact (n = 7–8) hearts. Adenylyl cyclase activity upon NaF stimulation: 185 ± 8 pmol/mg/min for WT-sham; 128 ± 10 pmol/mg/min for WT-TAC; 151 ± 6 pmol/mg/min for PI3Kγinact-sham; 162 ± 10 pmol/mg/min for PI3Kγinact-TAC. *P < 0.001 ISO versus basal. (c) Myocardial βAR/Gs coupling (percentage of high affinity) in sarcolemmal membranes prepared from hearts of WT sham (n = 3), WT TAC (n = 4), and PI3Kγinact (n = 3) mice. *P < 0.01 WT TAC versus either WT sham or PI3Kγinact TAC. (d) Proposed model of the mechanism by which overexpression of PI3Kγinact transgene prevents βAR downregulation. Overexpression of PI3Kγinact leads to a competitive displacement of all PI3K isoforms from the βARK1/PI3K complex. Following agonist stimulation, the translocation of βARK1 recruits inactive PI3K to the activated receptor complex attenuating receptor internalization. Inhibition of receptor internalization ultimately leads to receptor dephosphorylation and resensitization either at the cell surface or through enhanced cycling of receptor without being targeted for lysosomal degradation. Gs, Gαs subunit of heterotrimeric G protein.

Discussion

In the present investigation we identify a unique role for PI3K in regulating the level and sensitivity of βAR function in the heart and suggest an important role for βAR dysfunction in pressure overload–induced heart failure. We show that cardiac-targeted overexpression of a catalytically inactive PI3K prevents βAR downregulation and desensitization with chronic catecholamine administration and ameliorates the development of cardiac dysfunction under conditions of chronic in vivo pressure overload. Our data show that overexpression of PI3Kγinact in the hearts of transgenic mice leads to a competitive displacement of all PI3K isoforms from the βARK1/PI3K complex such that translocation of βARK1 recruits catalytically inactive PI3K to activated receptors, leading to the inhibition of receptor internalization (Figure 7d). Intriguingly, we also show that the deletion of PI3Kγ in the heart is insufficient to prevent βAR dysfunction despite its positive effect on adenylyl cyclase activity. These data suggest that the generation of PtdIns-3,4,5-P3 molecules localized within the activated receptor complex plays a critical role in regulating βAR recycling and preserving βAR function in vivo.

PI3K and βAR function.

βAR downregulation and desensitization are hallmarks of heart failure and are believed to be secondary to the chronic activation of the sympathetic nervous system and increased catecholamines that occur with circulatory failure (2, 26). Recent data show that preservation of βAR function through βARK1 inhibition improves cardiac function in experimental models of heart failure (3–5). The mechanism for this benefit, however, is not entirely clear since βARK1 inhibition was carried out using overexpression of the βARK1-ct peptide (c-terminal region of βARK1) that also has the ability to sequester Gβγ subunits and as a result could inhibit activation of Gβγ-mediated signals. In this regard, our present study highlights a novel strategy to preserve βAR function under conditions of catecholamine excess and heart failure upon chronic pressure overload by targeting the βARK1/PI3K interface. While both the PI3Kγinact and βARK-ct transgenes prevent receptor downregulation, the underlying mechanism for preservation of βAR function are different. The βARK-ct peptide sequesters liberated Gβγ subunits, thereby inhibiting βARK1-mediated phosphorylation of βARs (27). In contrast, overexpression of PI3Kγinact transgene does not inhibit receptor phosphorylation as we show by in vitro rhodopsin phosphorylation but, rather, prevents subsequent process involved in receptor internalization (8).

The effect on βAR function was found to be specific to the disruption of the βARK1/PI3K interaction, since mice that completely lack the PI3Kγ gene (PI3Kγ-KO) showed a similar downregulation of βARs and diminished agonist-stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity when exposed to chronic catecholamines. This is particularly interesting given the recently identified role of PI3Kγ in regulating adenylyl cyclase activity (9, 12). PI3Kγ-KO mice have been shown to have enhanced contractility and elevated basal and agonist-stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity (ref. 9; Figure 4c). Despite this enhanced adenylyl cyclase activity, however, chronic ISO administration leads to desensitization and downregulation of βARs. Importantly, βARK1-associated PI3K activity in the hearts of PI3Kγ-KO mice was similar compared with the WT, and we show that βARK1 interacts with the PI3Kα isoform in the hearts of these mice (10). Based on the phenotype of these two mouse models (PI3Kγinact and PI3Kγ-KO), we postulate that overexpression of the dominant negative PI3K transgene leads to a reduction in βARK1-associated PI3K activity, which plays a critical role in preventing the downregulation and desensitization of the βARs under conditions of chronic agonist stimulation. Furthermore, the membrane recruitment of PI3K appears to be an early event in the regulation of βAR function and is consistent with our in vitro studies showing its role in receptor internalization within minutes of agonist stimulation (10). Thus, our data identify a new role for PI3K in maintaining the level of βARs in the heart. Whereas PI3Kγ may directly regulate cyclase activity (9), the recruitment of any active PI3K isoform to the receptor complex promotes the downregulation of βARs. Our data have important implications regarding the potential development of PI3Kγ inhibitors to augment cardiac contractility (9). Without preventing the βARK1-mediated recruitment of active PI3K to the cell membrane, a selective inhibitor of PI3Kγ would not prevent the βAR abnormalities or the contractility defects in heart failure.

Resensitization allows βARs to renew their ability to respond to ligand and has been shown to require internalization into intracellular compartments where the acidic environment allows for dephosphorylation of the receptor (28, 29). An interesting finding of this study is that resensitization of βARs in vivo may occur under conditions that prevent receptor internalization despite continuous exposure to agonist. One potential explanation for this phenomenon is the targeting of phosphatases to agonist-occupied receptors (30, 31), which could promote dephosphorylation of the receptor at the plasma membrane without the cycling into early endosomes. Alternatively, it is possible that βARs are internalized but undergo rapid recycling without being targeted for lysosomal degradation, a process thought to require PI3K activity (32, 33). Future studies that use in vitro models of βAR desensitization will be required to determine the exact mechanism of βAR resensitization in this system. Finally, we cannot exclude the possibility that the PI3Kγinact transgene affects some other signaling pathway that ameliorates cardiac dysfunction, leading to a reversal in the βAR defect.

PI3K and downstream cellular signaling.

PI3Kγinact overexpression did not affect the immediate downstream signaling with either GPCR or growth factor stimulation and did not inhibit the development of cardiac hypertrophy to short-term pressure overload. Although basal pPKB levels are lower in the PI3Kγinact transgenic mice compared with the WT, acute and chronic stimulation leads to PKB activation possibly due to availability of liberated Gβγ to activate endogenous PI3Ks and/or through transactivation of tyrosine kinase receptors such as the epidermal growth factor (34, 35). This supports our understanding that PI3Kγinact overexpression specifically disrupts the βARK1/PI3K interaction without affecting the acute activation of receptor-mediated downstream PI3K signals. Increasing evidence supports a role for PI3K in determining cardiac growth (13). Cardiac overexpression of a catalytically inactive PI3Kα (dnPI3Kα) was shown to result in reduced heart weight and cardiomyocyte size compared with WT, whereas overexpression of constitutively active PI3Kα developed a hypertrophic phenotype suggesting a specific regulatory role for the PI3Kα isoform in the control of myocyte growth (13). Moreover, mice deficient in phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN) showed spontaneous cardiac hypertrophy and reduced contractility, indicating a role of phosphatidylinositol signaling in cardiac growth (9). In contrast, in our study mice overexpressing PI3Kγinact had no effect on cardiac growth under normal or stressed conditions. The likely explanation for the difference in the mouse phenotypes relates to the different transgenes that were used in the two studies. We overexpressed the inactive PI3Kγ isoform that contained all the domains except for the ATP-binding site. In contrast, the dnPI3Kα transgene used by Shioi et al. (13) lacked the PIK domain that is necessary for its interaction with βARK1 (8). Thus, overexpression of dnPI3Kα would not displace endogenous PI3K from βARK1, but would act to sequester adaptor proteins involved in PI3Kα signaling pathways. Our data in this study show that competitive displacement of PI3K from the βARK1 complex is critical to preserve βAR function and prevent βAR downregulation in chronic disease states.

In conclusion, we demonstrate a new role for PI3K in regulating GPCR signaling in vivo. Overexpression of catalytically inactive PI3Kγ displaces active endogenous PI3K from βARK1 and leads to preservation of βAR function under conditions of chronic catecholamine administration and chronic pressure overload. Targeting PI3Kγ directly would be insufficient as a therapeutic strategy, but, rather, one would need to disrupt recruitment of PI3K to activated βARs to prevent receptor desensitization and downregulation. While the increased contractile phenotype of the PI3Kγ-KO mice (9) suggests a direct action of PI3Kγ on the catalytic activity of adenylyl cyclase, displacement of endogenous active PI3K from βARK1 is necessary to modulate receptor function. Finally, we show that normalization of βAR function is associated with the amelioration of the heart failure phenotype induced by pressure overload and suggests that βAR dysfunction may be involved in the pathogenesis of this disease. These findings may have important clinical implications for the treatment of heart failure, where circulating catecholamines are known to be increased leading to marked βAR dysfunction. Inhibition of βAR-localized PI3K activity may therefore represent a novel therapeutic strategy to restore βAR function.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the NIH (grant HL-56687 to H.A. Rockman) and the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (to H.A. Rockman). J.J. Nienaber is a research fellow supported by the Stanley J. Sarnoff Endowment for Cardiovascular Science. H.A. Rockman is a recipient of a Burroughs Wellcome Fund Clinical Scientist Award in Translational Research. We thank Weili Zou for her excellent technical assistance and Liza Barki-Harrington for her valuable critique and scientific insights.

Footnotes

Jeffrey J. Nienaber and Hideo Tachibana contributed equally to this work.

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Nonstandard abbreviations used: β-adrenergic receptor (βAR); G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs); phosphatidylinositol (PtdIns); phosphoinositide kinase domain (PIK); phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-tri-phosphate (PtdIns-3,4,5-P3); inactive mutant of PI3Kγ (PI3Kγinact); PI3Kγ knockout (PI3Kγ-KO); hemagglutinin (HA); transverse aortic constriction (TAC); left ventricle (LV); PtdIns-3,4,5-tri-phosphate (PIP3); phospho-protein kinase B (pPKB); phospho-glycogen synthase kinase (pGSK); extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK); LV weight/body weight (LVW/BW); isoproterenol (ISO); immunoblotting (IB); c-terminal region of β-adrenergic receptor kinase-1 (βARK1-ct).

References

- 1.Hunt SA, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the evaluation and management of chronic heart failure in the adult: executive summary. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Revise the 1995 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure) Circulation. 2001;104:2996–3007. doi: 10.1161/hc4901.102568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohn JN, et al. Plasma norepinephrine as a guide to prognosis in patients with chronic congestive heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 1984;311:819–823. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198409273111303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rockman HA, Koch WJ, Lefkowitz RJ. Seven-transmembrane-spanning receptors and heart function. Nature. 2002;415:206–212. doi: 10.1038/415206a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akhter SA, et al. In vivo inhibition of elevated myocardial beta-adrenergic receptor kinase activity in hybrid transgenic mice restores normal beta-adrenergic signaling and function. Circulation. 1999;100:648–653. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.6.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harding VB, Jones LR, Lefkowitz RJ, Koch WJ, Rockman HA. Cardiac beta ARK1 inhibition prolongs survival and augments beta blocker therapy in a mouse model of severe heart failure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:5809–5814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091102398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foody JM, Farrell MH, Krumholz HM. β-Blocker therapy in heart failure: scientific review. JAMA. 2002;287:883–889. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.7.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lefkowitz RJ. G protein-coupled receptors. III. New roles for receptor kinases and beta-arrestins in receptor signaling and desensitization. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:18677–18680. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.30.18677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naga Prasad SV, et al. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase regulates beta2-adrenergic receptor endocytosis by AP-2 recruitment to the receptor/beta-arrestin complex. J. Cell Biol. 2002;158:563–575. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200202113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crackower MA, et al. Regulation of myocardial contractility and cell size by distinct PI3K-PTEN signaling pathways. Cell. 2002;110:737–749. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00969-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naga Prasad SV, Barak LS, Rapacciuolo A, Caron MG, Rockman HA. Agonist-dependent recruitment of phosphoinositide 3-kinase to the membrane by beta-adrenergic receptor kinase 1. A role in receptor sequestration. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:18953–18959. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102376200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vanhaesebroeck B, et al. Synthesis and function of 3-phosphorylated inositol lipids. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2001;70:535–602. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jo SH, Leblais V, Wang PH, Crow MT, Xiao RP. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase functionally compartmentalizes the concurrent G(s) signaling during beta2-adrenergic stimulation. Circ. Res. 2002;91:46–53. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000024115.67561.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shioi T, et al. The conserved phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway determines heart size in mice. EMBO J. 2000;19:2537–2548. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.11.2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naga Prasad SV, Esposito G, Mao L, Koch WJ, Rockman HA. Gbetagamma-dependent phosphoinositide 3-kinase activation in hearts with in vivo pressure overload hypertrophy. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:4693–4698. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.7.4693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaidarov I, Keen JH. Phosphoinositide-AP-2 interactions required for targeting to plasma membrane clathrin-coated pits. J. Cell Biol. 1999;146:755–764. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.4.755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma AD, Metjian A, Bagrodia S, Taylor S, Abrams CS. Cytoskeletal reorganization by G protein-coupled receptors is dependent on phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma, a Rac guanosine exchange factor, and Rac. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:4744–4751. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.8.4744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Z, et al. Roles of PLC-beta2 and -beta3 and PI3Kgamma in chemoattractant-mediated signal transduction. Science. 2000;287:1046–1049. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5455.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Esposito G, et al. Genetic alterations that inhibit in vivo pressure-overload hypertrophy prevent cardiac dysfunction despite increased wall stress. Circulation. 2002;105:85–92. doi: 10.1161/hc0102.101365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iaccarino G, Tomhave ED, Lefkowitz RJ, Koch WJ. Reciprocal in vivo regulation of myocardial G protein-coupled receptor kinase expression by beta-adrenergic receptor stimulation and blockade. Circulation. 1998;98:1783–1789. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.17.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choi DJ, Rockman HA. Beta-adrenergic receptor desensitization in cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 1999;31:321–329. doi: 10.1007/BF02738246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Subramaniam A, et al. Tissue-specific regulation of the alpha-myosin heavy chain gene promoter in transgenic mice. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:24613–24620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pitcher JA, Freedman NJ, Lefkowitz RJ. G protein-coupled receptor kinases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1998;67:653–692. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi DJ, Koch WJ, Hunter JJ, Rockman HA. Mechanism of beta-adrenergic receptor desensitization in cardiac hypertrophy is increased beta-adrenergic receptor kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:17223–17229. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.27.17223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cho MC, et al. Defective beta-adrenergic receptor signaling precedes the development of dilated cardiomyopathy in transgenic mice with calsequestrin overexpression. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:22251–22256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.32.22251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rockman HA, et al. Expression of a beta-adrenergic receptor kinase 1 inhibitor prevents the development of myocardial failure in gene-targeted mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:7000–7005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.7000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bristow MR, et al. Decreased catecholamine sensitivity and beta-adrenergic-receptor density in failing human hearts. N. Engl. J. Med. 1982;307:205–211. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198207223070401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koch WJ, et al. Cardiac function in mice overexpressing the beta-adrenergic receptor kinase or a beta ARK inhibitor. Science. 1995;268:1350–1353. doi: 10.1126/science.7761854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krueger KM, Daaka Y, Pitcher JA, Lefkowitz RJ. The role of sequestration in G protein-coupled receptor resensitization. Regulation of beta2-adrenergic receptor dephosphorylation by vesicular acidification. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:5–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perry SJ, Lefkowitz RJ. Arresting developments in heptahelical receptor signaling and regulation. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12:130–138. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)02239-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin F, Wang H, Malbon CC. Gravin-mediated formation of signaling complexes in beta 2-adrenergic receptor desensitization and resensitization. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:19025–19034. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.25.19025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shih M, Lin F, Scott JD, Wang HY, Malbon CC. Dynamic complexes of beta2-adrenergic receptors with protein kinases and phosphatases and the role of gravin. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:1588–1595. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.3.1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clague MJ, Urbe S. The interface of receptor trafficking and signalling. J. Cell Sci. 2001;114:3075–3081. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.17.3075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zerial M, McBride H. Rab proteins as membrane organizers. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;2:107–117. doi: 10.1038/35052055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saward L, Zahradka P. Angiotensin II activates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ. Res. 1997;81:249–257. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim J, Eckhart AD, Eguchi S, Koch WJ. Beta-adrenergic receptor-mediated DNA synthesis in cardiac fibroblasts is dependent on transactivation of the epidermal growth factor receptor and subsequent activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:32116–32123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204895200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]