Abstract

Infection by Staphylococcus aureus can result in severe conditions such as septicemia, toxic shock, pneumonia, and endocarditis with antibiotic resistance and persistent nasal carriage in normal individuals being key drivers of the medical impact of this virulent pathogen. In both virulent infection and nasal colonization, S. aureus encounters the host immune system and produces a wide array of factors that frustrate host immunity. One in particular, the prototypical staphylococcal superantigen-like protein SSL7, potently binds IgA and C5, thereby inhibiting immune responses dependent on these major immune mediators. We report here the three-dimensional structure of the complex of SSL7 with Fc of human IgA1 at 3.2 Å resolution. Two SSL7 molecules interact with the Fc (one per heavy chain) primarily at the junction between the Cα2 and Cα3 domains. The binding site on each IgA chain is extensive, with SSL7 shielding most of the lateral surface of the Cα3 domain. However, the SSL7 molecules are positioned such that they should allow binding to secretory IgA. The key IgA residues interacting with SSL7 are also bound by the leukocyte IgA receptor, FcαRI (CD89), thereby explaining how SSL7 potently inhibits IgA-dependent cellular effector functions mediated by FcαRI, such as phagocytosis, degranulation, and respiratory burst. Thus, the ability of S. aureus to subvert IgA-mediated immunity is likely to facilitate survival in mucosal environments such as the nasal passage and may contribute to systemic infections.

Keywords: immune evasion, mucosal immunity, antibody, Fc receptor, staphylococcal superantigen-like

Staphylococcus aureus is an important human pathogen causing conditions ranging from minor superficial skin infections to life-threatening syndromes, including sepsis, toxic shock syndrome, osteomyelitis, pneumonitis, and endocarditis. It is carried without symptoms in at least 20% of individuals (1, 2). The emergence in the 1960s of pandemic penicillin-resistant S. aureus has been followed by a variety of hospital-associated and community-associated methicillin-resistant strains (HA- and CA-MRSA) (2, 3). The increased prevalence of MRSA infections and corresponding rise in life-threatening syndromes have made it imperative to elucidate the mechanisms of pathogenesis for S. aureus. The interaction between S. aureus and the host is complex and is mediated by an array of bacterial proteins that both mediate the various pathologies and modify the immune system of the host (4–10).

SSL7 (formerly named SET1) is the first described member of a new family of putative S. aureus toxins, the staphylococcal superantigen-like (SSL) proteins (11, 12), related to the staphylococcal enterotoxins (SEs) or superantigens (13). The SSL proteins have ≈30% sequence identity with toxic shock syndrome 1 (TSST-1) and 25% or less identity with other SEs. Despite the sequence differences, the SSL proteins have a typical SE tertiary structure consisting of a distinct oligonucleotide/oligosaccharide binding (OB-fold) linked to a β-grasp domain (14–16).

Similar to the se genes, the ssl genes are located in a pathogenicity island (SaPIn2) and are likely to be significant virulence factors (12, 17, 18). Most healthy individuals have antibodies to SSL proteins (19), and the ssl genes exhibit marked allelic variance consistent with selective pressure from the host immune system (20). However, unlike SE, the SSL proteins do not have superantigen activity, but some have been shown to inhibit key molecules of the host immune system. Both SSL5 (21) and SSL11 (M. C. Chung, B.D.W., H. Baker, R. J. Langley, E. N. Baker, and J.D.F., unpublished data) interact with sialyl-Lex and related oligosaccharides, thereby inhibiting key cellular adhesion processes such as neutrophil transmigration. Notably, SSL7 exhibits multiple activities, including the binding of complement component C5 and serum and mucosal forms of IgA, thereby inhibiting both C5 and fragment crystalline (Fc) receptor for IgA (FcαRI)-mediated immunity (22, 23). Furthermore, SSL7 has been observed to alter cytokine secretion (12) and to bind, and be rapidly internalized by, monocytes and dendritic cells, but the ligands involved are yet to be identified (16, 19).

We have determined the 3.2 Å resolution crystal structure of SSL7 bound to Fc of human IgA1, which reveals the structural mechanism for evasion of IgA-mediated immunity by S. aureus. Notably, two SSL7 molecules bind the Fc, principally at the junction of the Cα2 and Cα3 domains, establishing a competitive binding mechanism for inhibition of FcαRI (24). The OB-fold of SSL7 is used for IgA recognition, which suggests that the β-grasp domain has another role such as the binding of C5. Site-directed mutagenesis of SSL7 and IgA confirmed that key binding residues for SSL7 and FcαRI are colocated on human IgA.

Results

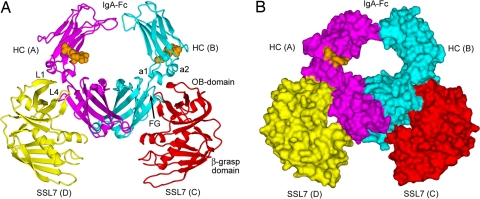

General Features of the Recognition of IgA by SSL7. The complex of SSL7 and human IgA1 Fc was determined to 3.2 Å resolution (Table 1). The complex has pseudo-2-fold symmetry, and two SSL7 molecules are bound to the Fc homodimer, where each SSL7 interacts principally with a single IgA heavy chain (Fig. 1). The main axes of the SSL7 and Fc molecules lie approximately in the same plane such that the complex has a relatively flat disk-like topography. The only protrusions from the flat faces of the disk are the N-linked carbohydrates of the Cα2 domains, but these glycans are mostly disordered, unlike their counterparts in IgG, which occupy the interface between the Cγ2 domains (25). The two SSL7 molecules, resembling the pincers of a crab, seize the Fc with two loops from the OB-fold (L1 and L4), which interact predominantly at the Cα2/Cα3 domain junctions of IgA. The SSL7 molecules also shield most of the lateral surfaces of the two Cα3 domains, but the only additional contacts involve the N-terminal α-helix of SSL7. Interestingly, the SSL7 β-grasp domains extend beyond the end of the Fc and are around the expected position of the tail pieces and J-chain that are responsible for the formation of polymeric IgA. We have demonstrated previously that SSL7 binds with high affinity to IgA found in mucosal secretions (22). The relatively flat topography of the current complex may allow the Fc of dimeric IgA to interact concurrently with both secretory component and SSL7.

Table 1.

Crystallographic statistics

| Parameter | Value* |

|---|---|

| Space group | P212121 |

| Unit cell dimensions, Å | a = 71.31, b = 109.26, c = 170.86 |

| Resolution range, Å | 50–3.20 (3.31–3.20) |

| Data completeness, % | 98 (97) |

| Average multiplicity | 6.3 (6.1) |

| Rsym | 0.103 (0.362) |

| Mean I/σ, I | 10.0 (2.8) |

| Rwork (Rfree) | 0.23 (0.31) |

| rmsd bond lengths, Å | 0.008 |

| rmsd bond angles, ° | 1.5 |

| Ramachandran plot† | |

| Most favored regions, % | 70.9 |

| Additional allowed regions, % | 26.1 |

| Generously allowed regions, % | 2.2 |

| Disallowed regions, % | 0.9 |

*Values in parentheses are for the highest-resolution shell.

†Prepared with Procheck, version 3.3.

Fig. 1.

Crystal structure of SSL7 bound to Fc of human IgA1. (A) Ribbons-style representation with the IgA-Fc homodimer (heavy chains, magenta and cyan; carbohydrates, orange CPK spheres) and the two SSL7 molecules (yellow and red) with secondary structure displayed. (B) Solvent-accessible surface view of the SSL7 complex with IgA-Fc.

The SSL7 Interface with IgA Is Discontinuous and Extensive.

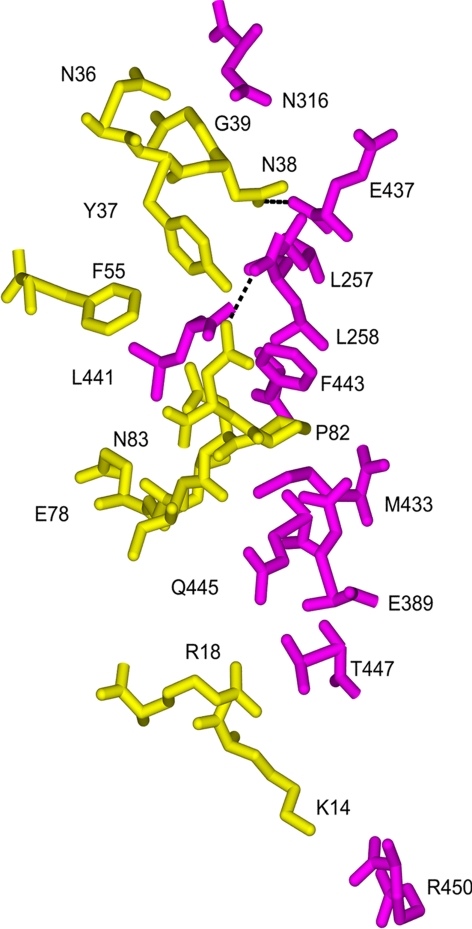

Although there are several differences in the residues participating in the binding of IgA for the two SSL7 molecules (Table 2), the conservation of the two interfaces is substantial (Fig. 2). The SSL7 footprint on IgA extends vertically down the Fc from the lower Cα2 domain to the end of the Cα3 domain; however, nearly all of the interactions occur at the Cα2/Cα3 junction (Figs. 2 and 3). In IgA, this binding “hot spot” is a shallow irregularly shaped cavity formed between Cα2 residues from two α-helices (a1, L257 and L258; a2, N316 and H317), and Cα3 residues from the C-strand (E389) and the FG loop (M433, E437, L441, F443, and Q445). Near the middle of the Cα2/Cα3 junction, the side chain of Fc residue L441 forms an obvious protrusion, which facets neatly into a hydrophobic slot in the SSL7 molecules (lined by F55, E78, L79, V89, and F179) and packs closely with the side chain of SSL7 residue F55. In SSL7, a loop (L1, residues 36–38) from the OB-fold binds adjacent to the protruding L441 in the Fc cavity formed mainly by Cα2 residues, whereas a second loop (L4, residues 78–83) penetrates with P82 in the lead into the pocket formed entirely by Cα3 residues. Thus far, all alleles of SSL7 are likely to bind IgA because the sequence of the L1-and L4-binding regions are identical in SSL7 from S. aureus strains 4427, MW2, N315, Mu50, GL1, GL10, and NCTC8325.

Table 2.

Interactions of SSL7 with IgA

| SSL7 site 1 residue (site 2) | Fc residue |

|---|---|

| Y37* N38, R85 (Y37) | L257 |

| N83* (D81, P82, N83*) | L258 |

| (N36) | E313 |

| N36, N38, G39 (N36*, N38, G39) | N316 |

| N36 | H317 |

| P82 (P82) | E389 |

| L79, I80 (I80) | M433 |

| (N38) | H436 |

| N38* (N38*) | E437 |

| (N38) | L439 |

| (F55) | P440 |

| F55, E78, V89, F179 (F55, E78) | L441 |

| Y37 | A442 |

| Y37, L79, D81, P82 (Y37, L79, D81, P82) | F443 |

| L79 | T444 |

| L79 (L79) | Q445 |

| R18 (R18) | T447 |

| (K14*) | D449 |

| K14 (K14*) | R450 |

| Y11† | E357 |

| Y11† | A360 |

*SSL7 residues hydrogen bonding with Fc residue.

†Subsite where SSL7 (chain D) interacts with the partner heavy chain (i.e., chain B).

Fig. 2.

Conserved SSL7 interactions with the Fc of human IgA1. Only those residues that participated in atomic contacts or hydrogen bonding (dashed lines) for both SSL7 (yellow) molecules bound to IgA-Fc (magenta) are displayed. A full list of residues involved in the different interfaces is presented in Table 2.

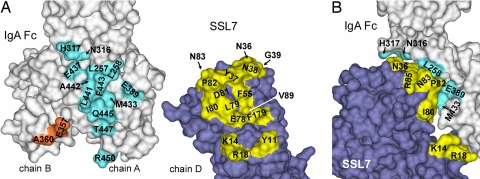

Fig. 3.

Surface views of binding regions on SSL7 and the Fc of human IgA1. (A) Residues at the interface (≤4 Å) are mapped to the molecular surfaces of the Fc (chain A, cyan; chain B, orange) and SSL7 (chain D, yellow) for one complex of SSL7 and the Fc. (B) Side view of the interaction between SSL7 and the Fc.

A second and distinct interface involves the N-terminal helix of SSL7 interacting with the end of the Fc (Figs. 2 and 3). Two SSL7 residues (K14 and R18) participate in interactions with the final G-strand of Cα3 (T447 and R450). In one SSL7 molecule (chain D), Y11 contacts the Fc residues A360 and E357, but these interactions occur with the second heavy chain (chain B) Cα3 domain (Fig. 3). Because of the observed differences, the smaller interface is unlikely to contribute significantly to SSL7 binding of IgA. However, the SSL7 interactions near the end of the Fc have led to the steric shielding of nearly all of the lateral surfaces of the two Cα3 domains.

Mutagenesis Confirms the Role of Key SSL7 Residues in Binding IgA.

Based on the three-dimensional structure of the SSL7 complex with IgA, individual point mutations were made to SSL7 residues N38, R44, L79, P82, and N83, and the effect on the SSL7 interaction with IgA was measured by biosensor analysis (Table 3). SSL7 mutant L79A had a 91-fold reduction in affinity compared with wild-type (WT) SSL7. The role of L79 in SSL7 binding of IgA is substantial through interactions with Fc residues F443, Q445, and M433 (Table 2 and Fig. 2). Furthermore, the L79 side chain also contributes to the hydrophobic environment of the cleft on SSL7 that accommodates L441 from Fc. Binding to IgA was reduced 35-fold compared with wild-type SSL7 for the N38T and P82A mutants, confirming the dominant roles of the OB-fold L1 and L4 loop regions, respectively. Mutation of SSL7 residues N83 (near the periphery of the interaction) and R44 (not part of the binding interface) only had modest effects on IgA-binding activity (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparative affinities of SSL7 mutants in binding human serum IgA

| SSL7 mutant | Kd × 10−6 M | Change, -fold |

|---|---|---|

| SSL7 wild type* | 0.0011 | 1 |

| N38T | 0.038 | 35 |

| R44A | 0.0036 | 3.2 |

| L79A | 0.1 | 91 |

| P82A | 0.039 | 35 |

| N83A | 0.004 | 4 |

*From ref. 22.

The Same Binding Site on IgA Is Recognized by SSL7 and FcαRI.

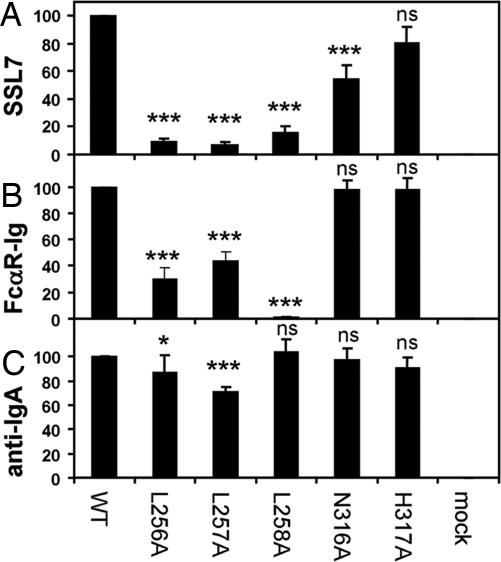

We previously identified the Cα2/Cα3 junction, and in particular the Cα3 domain FG loop sequence PLAF (Fc residues 440–443) were critical for binding to SSL7 and FcαRI (23). This finding is now confirmed in the three-dimensional structure of SSL7 and Fc, where both L441 and F443 are prominent interface residues (Table 2 and Figs. 2 and 3). We generated cell surface-expressed IgA-Fc mutants to examine the relative contribution of Cα2 residues from the a1- and a2-helices. The L256A and L257A mutations in the a1-helix were the most deleterious, reducing SSL7 binding 13-fold and 15-fold, respectively, followed by a 6.5-fold decrease for the L258A mutant Fc (Fig. 4). Interestingly, L256 does not contact SSL7, but its side chain is buried and packed against W315 and P251 in the core of the Cα2 domain, and its mutation has probably altered the conformation of the AB loop that contains the a1-helix. In contrast, both L257 and L258 participate in multiple interactions with the L1 loop region of SSL7 (Figs. 2 and 3), consistent with the reduced activity upon mutation. Mutations in the Cα2 EF loop a2-helix were less disruptive, with the N316A mutation reducing binding 1.8-fold, whereas the effect of the H317A mutation was negligible. In the complex, both of these Fc residues are located at the edge of the binding cavity that accommodates the L1 loop region of SSL7, and H317 was only observed to contact SSL7 in one of the two interactions (Table 2 and Figs. 2 and 3).

Fig. 4.

Mutagenesis of key residues on the Fc of human IgA1 confirms overlapping binding sites for SSL7 and FcαRI. (A–C) The IgA-Fc fusion proteins (WT and mutants, L256A, L257A, L258A, N316A, and H317A) were transiently expressed on CHOP cells and were analyzed by flow cytometry for binding of SSL7 (A), FcαRI-Ig fusion (B), and anti-IgA (C). The anti-IgA polyclonal antiserum binding of the various IgA-Fc fusion proteins was comparable with WT (90–103%) or modestly reduced (L256A mutant, 87%; L257A mutant, 71%). Binding data (mean ± SD; n = 4) are expressed as percent normalized by WT IgA Fc. ANOVA (ns, not significant P > 0.05; *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001) was performed with a Dunnett multiple comparison test (Prism 5 version 5.00, GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA) on data before normalization.

Activities of the Cα2 Fc mutants were also tested for binding to FcαRI. In contrast to SSL7 binding, the L256A and L257A Fc mutations resulted in modest reductions (3.3-fold and 2.3-fold, respectively) in FcαRI binding. Notably, the L258A mutant displayed >100-fold reduction in FcαRI-binding activity. Likewise, other studies found that L257R (26) and L258R (27) mutant IgAs were inactive in FcαRI binding. Mutation of N316A and H317A had no effect on the binding of FcαRI (Fig. 4). Thus, the Cα2/Cα3 domain junction of IgA is critical for binding both SSL7 and FcαRI (24), but the relative contribution differs for key Fc residues in binding SSL7 and FcαRI, consistent with their recognition of overlapping yet not identical binding sites on IgA.

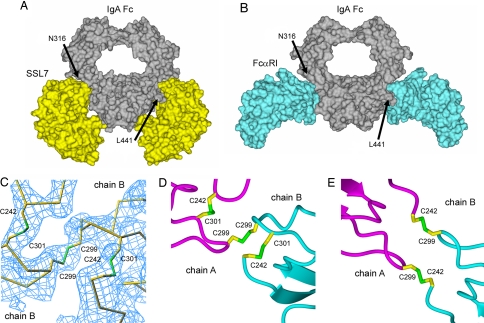

Comparison of Structures of SSL7 and FcαRI Bound to IgA-Fc.

The overlapping binding sites for SSL7 and FcαRI [Protein Data Base (PDB) ID code 1OW0] (24) are obvious from examination of their complexes with the Fc of human IgA1 (Fig. 5). The average total surface area buried at the interface of SSL7 and IgA is 1,678 Å2, i.e., 1,775 Å2 and 1,584 Å2 for each of the SSL7-Fc pairings. A similar total buried surface area of 1,654 Å2 occurs in the interaction of FcαRI with Fc (1,656 Å2 and 1,651 Å2), but both protein and carbohydrate residues of FcαRI contact the IgA ligand (24). In contrast, whereas the SSL7 molecules cover most of the Cα3 domains, the FcαRI grasps the Fc like bent fingers (Fig. 5B), which is perhaps a steric requirement of this receptor normally being anchored in, and “standing up” from, the cellular membrane (24, 28).

Fig. 5.

Comparison of the structures of SSL7 and FcαRI bound to Fc of human IgA1. (A and B) Surface views of the SSL7 complex (A) and FcαRI complex (B) (PDB code 1OW0) bound to IgA-Fc are shown. (C) Electron density (Fo − Fc at 2.5 σ) for the SSL7-bound Fc with the regions of polypeptide containing the Cα2 domain disulfides omitted during map calculation. (D and E) Disulfide bridges are shown for the Cα2 domain pairings of IgA-Fc structures bound to SSL7 (D) and FcαRI (E).

Compared with the near perfect pseudo-2-fold symmetry of the IgA-Fc in complex with FcαRI (24), the Fc bound to SSL7 has adopted noticeable asymmetry. Most of the differences occur near the top of the Cα2 domains in the polypeptide segments surrounding the half-cystine residues, which are displaced in Cα positions by up to 9 Å (C242, 7.5 Å; C299, 9.0 Å; C301, 8.5Å) when the two heavy-chain Cα3 domains are superimposed. In the lower portions of the Cα2 domains, the structural differences are minimal (≤0.6 Å Cα displacements), and consequently the Cα2/Cα3 domain junctions where the SSL7 bind are almost identical. Differences in Cα2 domains are attributable to the disulfide pairing of these domains in the SSL7–Fc complex. Examination of the electron density maps around the disulfides of the Fc revealed a single interchain pairing of C299–C299 and novel intradomain Cα2 disulfides resulting from C242–C301 pairings (Fig. 5 C and D). In contrast, the Fc in complex with FcαRI has two interchain disulfides involving C242–C299 (Fig. 5E), which leaves the two C301 residues with free sulfhydryl groups (24). This alternative disulfide connectivity has resulted in a 2-fold symmetrical association of the Cα2 domains.

Discussion

The 3.2 Å resolution structure of SSL7 bound to the Fc of human IgA1 has provided the first glimpses into how S. aureus has adapted for survival in mucosal and systemic environments without elimination by IgA-mediated immunity. This prototypical member of the SSL family of exotoxins (12) can bind with high affinity by comprehensively shielding both sides of the lower half of the Fc, apparently without blocking the additional components (tailpieces, J-chain, and secretory component) that assemble to form dimeric and secretory IgA (22). The Fc residues recognized by SSL7 occur in all human IgA subclasses and allotypes. Furthermore, SSL7 competitively inhibits the leukocyte IgA receptor, FcαRI, which binds to an overlapping site at the Cα2/Cα3 domain junction (24).

In IgA, the Cα2/Cα3 junction appears to be a hot spot for recognition by diverse molecules such as SSL7, FcαRI (CD89) (24, 26, 27), as well as proteins from group A streptococci (M proteins; Sir22/Arp4), group B streptococci (β-protein) (29, 30), and it forms part of the human polymeric Ig receptor-binding site (31). The Cγ2/Cγ3 domain junction of IgG is also a target site for multiple binding proteins, including the neonatal Fc receptor (32), staphylococcal protein A (25), autoantibodies or rheumatoid factors (33), viral receptors (34), and Trim21 or Ro52 (35). Thus, rather than being an inert junction of two antibody constant domains, they are sites of functional diversity, and so it is not surprising that pathogens target these junctions. Indeed, SSL7 species cross-reactivity (22), combined with a phylogenetic analysis of IgA and FcαRI sequences, found that these proteins have been coevolving under the pressure of pathogenic IgA-binding proteins such as SSL7. This work predicted residues in the Cα2 a2-helix affect SSL7 binding (36).

Recognition of IgA by SSL7 is predominantly through the OB-fold and, as an example of an OB-fold interaction with an Ig, SSL7 further illustrates the functional adaptability of the OB-fold. The OB-fold is found in all existent species from archaea to mammals, and these domains commonly bind oligonucleotides (RNA and DNA) or oligosaccharides, although protein binding and enzymatic activities have also been described (15). The OB-fold consists of a five-stranded β-barrel capped with an N-terminal α-helix, and ligand-binding sites are adaptable, often involving the face of the β-barrel and combinations of the variable loops. Nucleic acid binding usually involves the L2 and L4 loops, whereas the L3 and L4 loops have been described to bind oligosaccharide in the shigella-like toxin (15). In the SSL7 interaction with IgA, the L1 and L4 loops provide the major binding contacts, and the capping α-helix of the OB-fold is also involved (Figs. 1 and 2).

The β-grasp domain of SSL7 is not involved in binding IgA, but it extends beyond the globular Cα3 domains in a position that should not interfere with the assembly of tail pieces and J-chain in dimeric IgA. The C5 inhibitory activity of SSL7 occurs without obvious interference by IgA, and through implication we suggest the β-grasp domain to be the most likely candidate for SSL7-mediated inhibition of complement lysis and C5a-mediated chemotaxis. In support of the β-grasp domain of SSL7 having a C5 inhibitory function, it has been reported that the chemotaxis inhibitory protein of S. aureus (CHIPS), which consists of an isolated β-grasp domain, binds both C5aR and the formylated peptide receptor (37, 38).

In complex with SSL7, the IgA-Fc adopts an asymmetric conformation around the pairing of Cα2 domains. In contrast, the IgA-Fc bound to FcαRI is almost perfectly symmetrical because of different interchain and intradomain disulfide linkages in the two Fc structures (Fig. 5 C–E). These two Fcs both lack C241, and hence the disulfide connectivity may differ from intact IgA. With this caveat in mind, the two Fc structures indicate that pairing of Cα2 domains can generate different conformational states of IgA, possibly by disulfide interchange reactions. These different IgA conformers may alter interactions with the polymeric Ig receptor and so have a role in the assembly of secretory IgA. Indeed, late in transcytosis a disulfide interchange reaction occurs that results in a disulfide bond between IgA at C311 and the extracellular domain 5 (EC5) of the polymeric Ig receptor (39). The C311 side chain exists as a free sulfhydryl in both the FcαRI- and SSL7-bound IgA-Fc molecules, but its relative position differs by 2.7 Å in the two SSL7-bound heavy-chain conformers. Hence, disulfide-bonding patterns may contribute to generating distinct conformations of IgA, possibly with different functions. Furthermore, conformational plasticity of the Fc is supported by the finding that covalent binding of secretory component to dimeric IgA is optimized when the IgA is first treated in a redox buffer to facilitate disulfide/thiol interchange reactions (40).

This work and previous mutagenesis (23) have confirmed the structural and functional importance of the Cα2/Cα3 domain junction for binding of SSL7 and FcαRI. Circulating and secreted IgA differ in form and function (41), and SSL7 binds both with high affinity (22). Because SSL7 binds serum IgA a role in inhibiting FcαRI-mediated effector functions in S. aureus systemic infections is feasible (29, 42, 43). However, the topography of the SSL7 interaction with Fc may reflect adaptation for its known binding of secretory IgA (22), thereby facilitating mucosal colonization by S. aureus. The existence of functionally equivalent, although unrelated, proteins from group A and group B streptococci (29, 30), themselves often mucosal pathogens, suggests the mucosal response is the primary target of these IgA-binding proteins. Therefore, the SSL7 protein of S. aureus provides an elegant example of how a bacterial pathogen evades IgA-mediated immunity.

Materials and Methods

Production of Recombinant IgA-Fc and SSL7. A construct encoding a heavy-chain leader sequence (TIB142; American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) and an IgA-Fc region (C242 to P455; IgA1 myeloma Bur numbering) from IMAGE clone 4701069 (GenBank accession no. BC016369) was expressed from pAPEX-3p-X-DEST (pBAR424), a Gateway RfA cassette (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) derivative of pAPEX-3p (44). The IgA-Fc was produced by transfection of HEK293EBNA cells with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and selection with 2 μg/ml puromycin (Sigma, Melbourne, Australia). The IgA-Fc was affinity-purified by using thioredoxin-SSL7 coupled Sepharose (GE, Melbourne, Australia) and eluted with 50 mM glycine (pH 11.5).

The SSL7 gene used was from a S. aureus isolate (strain 4427) from Greenlane (GL) hospital, Auckland New Zealand, and the production of recombinant SSL7 (GL1) has been described previously (22). Mutants at individual residues of SSL7 were produced by splice overlap PCR as described previously (45).

Purification of IgA and Assay of SSL7-Binding Activity.

Human IgA was affinity-purified from serum by using SSL7-Sepharose (22). IgA was eluted with 50 mM glycine (pH 3), neutralized with 1 M Tris (pH 8.0), further purified on a Superdex 200 FPLC column, and used to assay the IgA-binding activity of SSL7 as described previously (22).

Transferrin Receptor-IgA-Fc Fusion Protein and IgA-Fc Mutants.

WT and mutant IgA1 Fc regions were expressed on CHOP cells as fusion proteins with the transmembrane region of the transferrin receptor and assayed for SSL7 and FcαRI-Ig-binding activities as described previously (23).

Crystallization and Structure Determination.

Cocrystals of SSL7 (9.7 mg/ml) and IgA-Fc (7.0 mg/ml) were generated by vapor diffusion against 12% (wt/vol) PEG 8000/66 mM sodium cacodylate, pH 6.5/130 mM calcium acetate. Data were obtained at 100 K by using a MicroMax007/R-Axis IV++ rotating anode system (Rigaku, The Woodlands, TX). Data were processed with the HKL program suite, version 1.96.6 (46), the structure determined by molecular replacement (PDB codes 1OW0 and 1V1P) and refined by using standard procedures within the CCP4, version 6.0.0 (47) and CNS, version 1.0 (48) program packages. Data collection and crystallographic refinement statistics are presented in Table 1.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia (P.A.R., B.D.W., and P.M.H.) and the Health Research Council of New Zealand (J.D.F.). P.A.R. is the recipient of an R. D. Wright Career Development Award from the NHMRC.

Abbreviations

- C5

complement component 5

- Fc

fragment crystalline

- FcαRI

Fc receptor for IgA

- OB

oligonucleotide/oligosaccharide-binding

- SE

staphylococcal enterotoxin

- SSL

staphylococcal superantigen-like.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: SSL7 is the subject of a filed provisional patent application.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID code 2QEJ).

References

- 1.Cole AM, Tahk S, Oren A, Yoshioka D, Kim YH, Park A, Ganz T. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2001;8:1064–1069. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.8.6.1064-1069.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grundmann H, Aires-de-Sousa M, Boyce J, Tiemersma E. Lancet. 2006;368:874–885. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68853-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bishop EJ, Howden BP. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2007;12:1–22. doi: 10.1517/14728214.12.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Labandeira-Rey M, Couzon F, Boisset S, Brown EL, Bes M, Benito Y, Barbu EM, Vazquez V, Hook M, Etienne J, et al. Science. 2007;315:1130–1133. doi: 10.1126/science.1137165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rooijakkers SH, Ruyken M, Roos A, Daha MR, Presanis JS, Sim RB, van Wamel WJ, van Kessel KP, van Strijp JA. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:920–927. doi: 10.1038/ni1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Voyich JM, Braughton KR, Sturdevant DE, Whitney AR, Said-Salim B, Porcella SF, Long RD, Dorward DW, Gardner DJ, Kreiswirth BN, et al. J Immunol. 2005;175:3907–3919. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rooijakkers SH, van Kessel KP, van Strijp JA. Trends Microbiol. 2005;13:596–601. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iwatsuki K, Yamasaki O, Morizane S, Oono T. J Dermatol Sci. 2006;42:203–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foster TJ. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:948–958. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Kessel K, Veldkamp KE, Pesschel A, de Haas C, Verhoef J, van Strijp J. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003;531:341–349. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0059-9_28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lina G, Bohach GA, Nair SP, Hiramatsu K, Jouvin-Marche E, Mariuzza R. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:2334–2336. doi: 10.1086/420852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams RJ, Ward JM, Henderson B, Poole S, O'Hara BP, Wilson M, Nair SP. Infect Immun. 2000;68:4407–4415. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.8.4407-4415.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Proft T, Fraser JD. Clin Exp Immunol. 2003;133:299–306. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02203.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arcus VL, Langley R, Proft T, Fraser JD, Baker EN. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:32274–32281. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203914200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arcus V. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2002;12:794–801. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00392-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Shangiti AM, Naylor CE, Nair SP, Briggs DC, Henderson B, Chain BM. Infect Immun. 2004;72:4261–4270. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.7.4261-4270.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuroda M, Ohta T, Uchiyama I, Baba T, Yuzawa H, Kobayashi I, Cui L, Oguchi A, Aoki K, Nagai Y, et al. Lancet. 2001;357:1225–1240. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)04403-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fitzgerald JR, Reid SD, Ruotsalainen E, Tripp TJ, Liu M, Cole R, Kuusela P, Schlievert PM, Jarvinen A, Musser JM. Infect Immun. 2003;71:2827–2838. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.5.2827-2838.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Shangiti AM, Nair SP, Chain BM. Clin Exp Immunol. 2005;140:461–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02789.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baba T, Takeuchi F, Kuroda M, Yuzawa H, Aoki K, Oguchi A, Nagai Y, Iwama N, Asano K, Naimi T, et al. Lancet. 2002;359:1819–1827. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08713-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bestebroer J, Poppelier MJ, Ulfman LH, Lenting PJ, Denis CV, van Kessel KP, van Strijp JA, de Haas CJ. Blood. 2007;109:2936–2943. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-015461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Langley R, Wines B, Willoughby N, Basu I, Proft T, Fraser JD. J Immunol. 2005;174:2926–2933. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wines BD, Willoughby N, Fraser JD, Hogarth PM. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:1389–1393. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509334200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herr AB, Ballister ER, Bjorkman PJ. Nature. 2003;423:614–620. doi: 10.1038/nature01685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deisenhofer J. Biochemistry. 1981;20:2361–2370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pleass RJ, Dunlop JI, Anderson CM, Woof JM. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:23508–23514. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.33.23508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carayannopoulos L, Hexham JM, Capra JD. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1579–1586. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wines BD, Sardjono CT, Trist HH, Lay CS, Hogarth PM. J Immunol. 2001;166:1781–1789. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.3.1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woof JM. Biochem Soc Trans. 2002;30:491–494. doi: 10.1042/bst0300491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pleass RJ, Areschoug T, Lindahl G, Woof JM. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:8197–8204. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009396200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lewis MJ, Pleass RJ, Batten MR, Atkin JD, Woof JM. J Immunol. 2005;175:6694–6701. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.6694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burmeister WP, Huber AH, Bjorkman PJ. Nature. 1994;372:379–383. doi: 10.1038/372379a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Corper AL, Sohi MK, Bonagura VR, Steinitz M, Jefferis R, Feinstein A, Beale D, Taussig MJ, Sutton BJ. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:374–381. doi: 10.1038/nsb0597-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sprague ER, Wang C, Baker D, Bjorkman PJ. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e148. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.James LC, Keeble AH, Khan Z, Rhodes DA, Trowsdale J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:6200–6205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609174104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abi-Rached L, Dorighi K, Norman PJ, Yawata M, Parham P. J Immunol. 2007;178:7943–7954. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.7943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haas PJ, de Haas CJ, Poppelier M. J., van Kessel KP, van Strijp JA, Dijkstra K, Scheek RM, Fan H, Kruijtzer JA, Liskamp RM, et al. J Mol Biol. 2005;353:859–872. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Postma B, Poppelier MJ, van Galen JC, Prossnitz ER, van Strijp JA, de Haas CJ, van Kessel KP. J Immunol. 2004;172:6994–7001. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.11.6994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chintalacharuvu KR, Tavill AS, Louis LN, Vaerman JP, Lamm ME, Kaetzel CS. Hepatology. 1994;19:162–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jones RM, Schweikart F, Frutiger S, Jaton JC, Hughes GJ. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1429:265–274. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(98)00239-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Egmond M, van Garderen E, van Spriel AB, Damen CA, van Amersfoort ES, van Zandbergen G, van Hattum J, Kuiper J, van de Winkel JG. Nat Med. 2000;6:680–685. doi: 10.1038/76261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van Egmond M, Damen CA, van Spriel AB, Vidarsson G, van Garderen E, van de Winkel JG. Trends Immunol. 2001;22:205–211. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)01873-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Monteiro RC, Van De Winkel JG. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:177–204. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Evans MJ, Hartman SL, Wolff DW, Rollins SA, Squinto SP. J Immunol Methods. 1995;184:123–138. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(95)00093-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hudson KR, Robinson H, Fraser JD. J Exp Med. 1993;177:175–184. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.1.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bailey S. Acta Crystallogr D. 1994;50:760–763. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, et al. Acta Crystallogr D. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]