Abstract

Disintegrins which contain an Arg-Gly-Asp sequence in their binding domains are antagonists of integrins such as αvβ3. The purpose of this study was to compare a range of disintegrins with different integrin selectivities for their binding behavior in vitro to vascular endothelial cells bearing αvβ3 and to cultured tumor cells which express αvβ3.

Methods

Five disintegrins (bitistatin, kistrin, flavoridin, VLO4 and echistatin) and a cyclic pentapeptide, c[RGDyK], were radiolabeled with 99mTc and tested for binding to cells in vitro.

Results

99mTc-kistrin, flavoridin and VLO4 had the highest binding, 99mTc-echistatin had moderate binding, and 99mTc-bitistatin and 99mTc-c[RGDyK] had low binding to cells. The observed binding was attributed to αvβ3 to various extents: echistatin, bitistatin > kistrin > flavoridin > VLO4. Cancer cells internalized bound disintegrins after binding, but endothelial cells did not. After binding to endothelial cells, 99mTc-kistrin was not displaced by competing peptide or plasma proteins.

Conclusions

These data suggest that radiolabeled kistrin, flavoridin and VLO4 may have advantages over labeled bitistatin and small cyclic peptides for targeting αvβ3 in vivo. Since receptor-bound radioligand is not internalized by endothelial cells, disintegrins may provide an advantage for targeting αvβ3 on vasculature because they bind strongly to surface receptors and are not readily displaced.

Keywords: Disintegrins, integrin αvβ3, angiogenesis, tumors, Tc-99m, c[RGDyK]

INTRODUCTION

The αvβ3 integrin (vitronectin receptor) is found on many types of cells, and influences cell adhesion and migration with effects on angiogenesis, restenosis, tumor cell invasion and atherosclerosis [1]. It binds ligands containing an Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) motif, as does its closely related integrin, αIIbβ3, which is found exclusively on platelets and megakaryocytes. Binding of RGD ligands occurs at a site in the β3 subunit [2]. Both of these integrins bind the ligands fibrinogen, fibronectin, vonWillebrand factor, vitronectin, thrombospondin and others [3]. Studies have shown that the integrin αvβ3 is highly expressed on the walls (endothelium) of actively growing blood vessels. The concentration of these receptors on endothelial cells is much higher in young, actively growing blood vessels (as in a tumor), compared with mature blood vessels (as in most of the body) [4]. This makes αvβ3 a potentially useful target for radioligands for imaging and therapy of tumors. It has been shown that angiogenesis can be prevented by anti-αvβ3 antibodies or by cyclic RGD-containing peptides. Importantly, blockade of αvβ3 receptors caused apoptosis of actively proliferating vascular cells but not of pre-existing vascular cells, indicating the selectivity of this targeting approach [4].

Integrin αvβ3 is also found on the surface of certain cancer cells, including melanoma, glioblastoma, breast carcinoma (including metastases) and osteosarcoma [5–8]. Other integrins have also been found on the surface of tumor cells; for example, in addition to αvβ3, melanoma cells express α1β1, α3β1 and α5β1. The expression of αvβ3, however, is highly correlated with degree of malignancy: the expression of β3 integrins on melanoma cells was restricted exclusively to cells in the vertical growth phase and metastatic lesions, the most aggressive phases of the malignant process [6].

Integrin αvβ3 is being actively investigated as a target for radiotracers in order to image tumor angiogenesis. When radiolabeled ligand for αvβ3 is injected into the bloodstream of a cancer patient, the radioligand would be expected to bind to αvβ3 receptors in actively growing vasculature of the tumor, permitting external detection of the higher concentration of radiotracer in the tumor compared with surrounding tissue. An advantage of this approach is that the radioligand would accumulate in the vasculature of virtually any type of solid tumor, and provide a method for locating a wide variety of cancer types.

Potential ligands for αvβ3 include antibodies [9], synthetic peptides and their conjugates [10], and disintegrins [11–13]. Disintegrins, the most potent known inhibitors of integrin function, were first identified as a family of αIIbβ3 antagonists found in the venoms of various snakes [14]. They comprise a class of cysteine-rich polypeptides which are constrained by internal disulfide linkages into multi-loop structures. An RGD or analogous sequence is found in all disintegrins, located in a mobile loop which projects 14–17 Å from the protein core [15], and is critical for the disintegrins’ binding to β3 integrins.

Studies by Juliano et al showed that several disintegrins (kistrin, echistatin and flavoridin) bind with high affinity to αvβ3 in a solid phase assay, and that they inhibited binding of cultured endothelial cells to vitronectin [11]. Other disintegrins tested had lower binding to αvβ3. Cultured endothelial cells also bound to the disintegrins bitistatin, echistatin, kistrin, flavoridin and the RGD-containing nondisintegrin mambin.

Bitistatin is the largest known monomeric disintegrin. Radiolabeled Bitistatin is currently being investigated for imaging platelet deposits in vivo [16]. It also showed initial promise for imaging tumors in mice, with tumor uptake of 12% ID/g [17]. Other disintegrins appear to have better selectivity for αvβ3, and thus may be better candidates for imaging tumor angiogenesis.

The purpose of this study was to compare 99mTc-Bitistatin with a range of disintegrins that have different integrin selectivities, all radiolabeled with 99mTc, for their binding in vitro to vascular cells bearing αvβ3 and to cultured tumor cells which express αvβ3.

METHODS

Source of ligands

Table 1 lists the amino acid sequences of polypeptides used in this study. Bitistatin was produced as a recombinant product [18]. Other disintegrins were produced by reversed-phase (RP) HPLC purification from freeze-dried natural snake venom (Miami Serpentarium, Punta Gorda, FL): kistrin (from Calloselasma rhodostoma venom) [19]; echistatin (from Echis carinatus) [20]; flavoridin (from Trimeresurus flavoviridis) [21]; and VLO4 (homodimer from Vipera lebetina obtusa) [22]. The active component was identified by its bioactivity (e.g., ability to inhibit platelet aggregation in human platelet-rich plasma, or ability to inhibit adhesion of cultured cells [22]). The active material was purified to a single peak on RP-HPLC. Protein purity was tested by SDS/PAGE and matrix-assisted laser-desorption ionization–time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI–TOF-MS), performed at the Wistar Mass Spectrometry Facility, Philadelphia, PA. Protein concentrations were determined by Lowry assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Synthetic cyclic peptides c[RGDyK] and c[RGDfV] were obtained from Bachem Bioscience, King of Prussia, PA.

Table 1.

| 10 ● | 20 ● | 30 ● | 40 ● | 50 ● | 60 ● | 70 *** ● | 80 ● | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rBitistatin | GSPPVCGNEI | LEQGEDCDCG | SPANCQDQCC | NAATCKLTPG | SQCNHGECCD | QCKFKKARTV | CRIARGDWND | DYCTGKSSDC | PWNH |

| Kistrin | ---GKECDCS | SPEN---PCC | DAATCKLRPG | AQCGEGLCCE | QCKFSRAGKI | CRIPRGDMPD | DRCTGQSADC | PRYH | |

| Flavoridin | ---GEECDCG | SPSN---PCC | DAATCKLRPG | AQCADGLCCD | QCRFKKKRTI | CRIARGDFPD | DRCTGLSNDC | PRWNDL | |

| Echistatin | -ECESGPCCR | NCKFLKEGTI | CKRARGDDMD | DYCNGKTCDC | PRNPHKGPAT | ||||

| VLO4 (dimer) | -MNSGNPCC | DPVTCKPRRG | EHCVSGPCCR | NCKFLNAGTI | CKRARGDDMN | DYCTGISPDC | PRNPW | ||

| c[RGDfV] | ----RGDfV- | ||||||||

| c[RGDyK] | ----RGDyK- |

Radiolabeling

Disintegrins or cyclic peptide were prepared for 99mTc labeling by coupling hydrazino nicotinate (HYNIC) groups to lysine sidechains using succinimidyl-hydrazinonicotinamide (SHNH) [23]. A 20:1 molar ratio of SHNH:polypeptide in borate buffer pH 8.5 was used. The products were purified by reversed-phase HPLC on a C18 column (300 Å pore size) (Varian, Palo Alto, CA) using a linear gradient of 0–50% acetonitrile in 0.1%TFA over 25 minutes and monitoring UV absorbance at 280 nm (Waters, Milford, MA). The collected peak was freeze-dried from mobile phase in 10 μg aliquots, which were then stored at −70°C. The number of HYNIC linkers attached per molecule was determined by hydrazone assay [24] and the protein concentration was determined by Lowry assay.

Aliquots were labeled by mixing with a 99mTc-tricine intermediate [25]. Lyophilized kit vials containing 54 mg tricine and 75 μg SnCl2 · 2H2O, pH 7.3, were prepared and stored at 4°C. For labeling, 1850 MBq of 99mTc sodium pertechnetate solution (Cardinal Health, Sharon Hill, PA) in 1 mL was added to a stannous tricine vial and vortexed for 1 minute. After standing at room temperature for 2 minutes, 0.1 - 0.3 mL of the contents were transferred to a freeze-dried vial containing 10 μg HYNIC-disintegrin or HYNIC-c[RGDyK]. After vortexing for 1 minute, the reaction mixture was allowed to stand for 60 minutes. The product was diluted with isotonic saline to the desired concentration.

Radiochemical purity of 99mTc-tricine was determined by instant thin layer chromatography using ITLC-SG (Gelman, Ann Arbor, MI). Colloid was assessed by developing the strip in 0.9% NaCl and free pertechnetate was assessed by developing the strip in 2:1 acetone:methylene chloride. Radiochemical purity of the labeled polypeptide was assessed by reversed-phase HPLC on a C18 column (300 Å pore size) using a linear gradient of 0–50% acetonitrile in 0.1%TFA over 25 minutes, with radiation monitoring (NaI well detector and Model 2600 scintillation spectrometer, Ludlum, Sweetwater, TX; AllChrom data acquisition system, Alltech, Deerfield, IL).

Cultured Cells

SK-MEL-28 human metastatic melanoma and MDA-MB-435S breast ductal carcinoma cells (both positive for αvβ3) were obtained from ATCC. MDA-MB-435S cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1U/mL Pen-strep, at 37°C in 100% air. SK-MEL-28 cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1U/mL Pen-strep, at 37°C in 5% CO2. Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVEC) (Cascade Biologics) and Microvascular Endothelial Cells (MVEC) (Cambrex) were cultured according to a previously published method [11]. Briefly, purchased EC were plated in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 20% fetal bovine serum, endothelial cell growth supplement (60 μg/ml), fungizone (2.5 μg/ml, and gentamicin (0.5 μg/ml). Cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. EC were passaged at a 1:3 ratio, and cultures from the 3rd and 4th passage were used for binding studies. The cells were tested to confirm the presence of specific integrins such as αvβ3, α5β1 and α2β1. The cell concentrations were determined with a hemacytometer and phase-constrast microscope. Cells were used for binding studies within 1 hour after detaching and resuspending them.

In vitro binding studies

Assays of binding to integrins on intact cells were performed with cultured HUVEC, MVEC (5 × 105 cells/ml in PBS, pH 7.3)[21], SK-MEL-28 and MDA-MB-435S cells (5 × 106 cells/ml in PBS, pH 7.3), supplemented with 0.5 mM Ca++ and 0.5 mM Mn++. Studies were performed at 37°C. Radioligand concentration was at 2 nM to simulate the conditions which would exist in vivo for diagnostic imaging studies at which radioligand concentrations would be kept low.

Rate of Binding

Radiolabeled disintegrin or peptide was added to the suspension of cells (final ligand concentration 2 nM) and maintained at 37°C in a water bath. At 10, 20, 30, 40 and 60 minutes after addition, triplicate 100 μL aliquots of the suspension were layered over 100 μL of 30% sucrose in a microfuge tube and centrifuged at 13,000 ×g for 3 minutes (Biofuge Pico, Sorvall, Asheville, NC). The supernatant was transferred to a clean tube for counting and the tip containing the cell pellet was amputated and placed in a second counting tube. Both tubes were counted in a well counter (Wizard 1480, Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences, Wellesley, MA). Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 2.5 mM EDTA to chelate divalent cations necessary for integrin binding. Bound radioligand was calculated as the percent of the total net counts which were found in the cell pellet.

Competition for αvβ3

To estimate what percentage of observed binding was due to binding to αvβ3, blocking studies were done in the presence of 10 μM c[RGDfV], which is highly selective for αvβ3 [26]. The blocking peptide was added to cells before addition of 99mTc labeled disintegrins (final concentration 2 nM). The suspension was incubated for 1 hr at 37°C. Bound tracer was separated from free by centrifuging through 30% sucrose at 13,000 × g. Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 2.5 mM EDTA. The percentage of binding which was due to binding to αvβ3 was calculated as: [(TotSpecBd − TotCompetBd)/TotSpecBd]*100, where TotSpecBd = % Total bound − % nonspecific bound, and TotCompetBd = % bound in presence of competing peptide − % nonspecific bound.

Internalization studies

Internalization of radiotracer into cells was determined after adding radioligand (final concentration 2nM) to a suspension of cells containing divalent cations. Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 2.5 mM EDTA. After 1 hour of binding, cells were diluted with acid (to pH 2) or EDTA (to 50 mM) and held for 15 min at 0°C to remove surface activity. The suspension was centrifuged at 6500 ×g, the supernatant removed by pipet, and the cell pellet was resuspended in 0.01M HCl or 10 mM EDTA. This was held for 15 min at 0°C, after which it was centrifuged through 30% sucrose at 13,000 × g. The experiment was repeated at 4°C (at which no internalization should occur), to verify that there was no internalization at low temperature. Supernatants, washes and pellets were counted in a gamma counter. Internalized radioligand was calculated as the percentage of added radioactivity which remained with the cell pellet after removing surface-bound radioactivity. Results were found to be equivalent with either acid or EDTA treatment.

Reversibility of radioligand binding to cell surface

This experiment was done to determine whether radioligand bound to the surface of endothelial cells could be displaced by excess competing ligand. Radioligand (99mTc-kistrin) was allowed to bind to MVEC for 1 hour as described above. At one hour, an aliquot was removed to determine the extent of binding as above. An excess of competing ligand was mixed with the remaining cell suspension (c[RGDfV], final concentration 8 μM). Incubation was continued at 37°C. At various times over the next 1 hour, triplicate samples were removed and separated over sucrose to determine the percent of radioligand bound. In a related experiment, 125I-Kistrin was allowed to bind to HUVEC for 1 hour, and then binding was challenged by diluting the suspension 5-fold with heparinized human plasma. As a control experiment, a 5-fold dilution was made with binding buffer instead of plasma. The cell suspensions were maintained at 37°C for another hour, during which time aliquots were taken at various intervals, layered over sucrose and centrifuged at 13,000×g to separate cells. Cells and supernatant were counted as described above.

Statistical Analysis

Comparisons between radioligands were performed by unpaired T-test. Groups were considered nonequal if p<0.05.

RESULTS

HYNIC coupling to disintegrins

The 20:1 molar ratio used in the reaction resulted in the following number of HYNIC groups per disintegrin molecule: bitistatin (2.1), kistrin (1.8), VLO4 (1.2), flavoridin (0.9), echistatin (1.1).

Radioligand binding to cells

All 99mTc-disintegrins and peptide reached maximal binding to cells within 60 minutes. The binding was dependent on the presence of divalent cations, as adding EDTA in place of cations abolished binding to all three cell types.

All 99mTc-disintegrins and peptide bound to HUVEC, but kistrin and VLO4 bound to a higher extent than flavoridin, which bound better than bitistatin or c[RGDyK] (Figure 1). 99mTc-echistatin had significantly lower binding to HUVEC than 99mTc-kistrin, but was not significantly different from other disintegrins.

Figure 1. Specificity of Binding of 99mTc-ligands to HUVEC.

Radioligands (2 nM) were allowed to bind to cells for 1 hour before separating cells from supernatant. Black bars: Total binding. White bars: Nonspecific Binding (in the absence of divalent cations). Grey bars: Binding in the presence of excess c[RGDfV] peptide. Data represent the mean of independent experiments. Error bars = 1 sd.

* Total binding > echistatin, bitistatin, c[RGDyK] (P<0.05)

** Total binding > flavoridin, bitistatin, c[RGDyK] (P<0.05)

*** Total binding > bitistatin, c[RGDyK] (P<0.05)

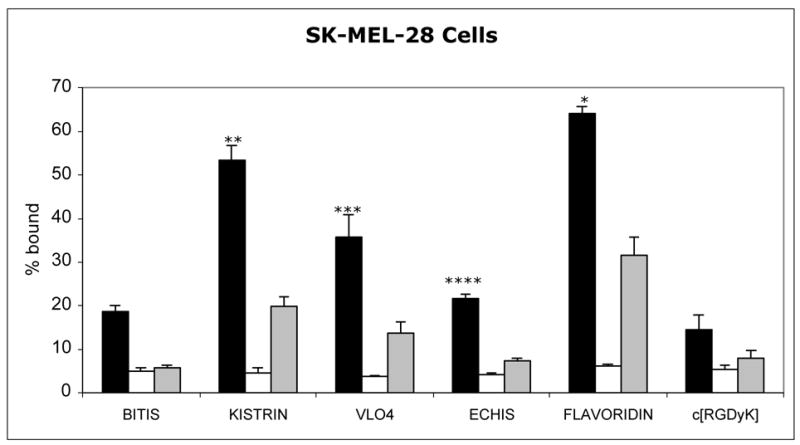

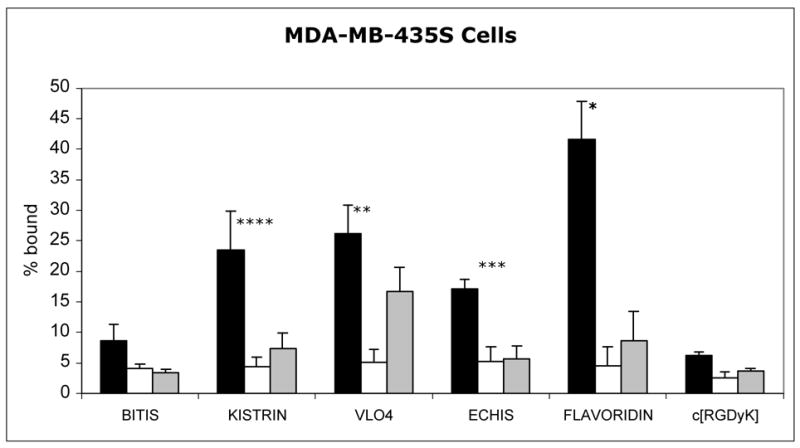

The order of binding was slightly different in cancer cells. Flavoridin had the highest binding to SK-MEL-28 cells (Figure 2), followed by kistrin with relatively high binding and VLO4 with moderate binding. The binding of 99mTc-echistatin was fairly low but was still higher than bitistatin. In MDA-MB-435S cells (Figure 3), 99mTc-flavoridin had the highest binding, while kistrin and VLO4 had moderate binding, and 99mTc-echistatin had slightly lower binding. Binding of 99mTc-bitistatin to both cancer cell lines was much lower, as was the binding of 99mTc-c[RGDyK].

Figure 2. Specificity of Binding of 99mTc-ligands to SK-MEL-28 Melanoma cells.

Radioligands (2 nM) were allowed to bind to cells for 1 hour before separating cells from supernatant. Black bars: Total binding. White bars: Nonspecific Binding (in the absence of divalent cations). Grey bars: Binding in the presence of excess c[RGDfV] peptide. Data represent the mean of independent experiments. Error bars = 1 sd.

* Total binding > all others (P<0.05)

** Total binding > VLO4, echistatin, bitistatin, c[RGDyK] (P<0.05)

*** Total binding > echistatin, bitistatin, c[RGDyK] (P<0.05)

**** Total binding > bitistatin (P<0.05)

Figure 3. Specificity of Binding of 99mTc-ligands to MDA-MB-435S breast cancer cells.

Radioligands (2 nM) were allowed to bind to cells for 1 hour before separating cells from supernatant. Black bars: Total binding. White bars: Nonspecific Binding (in the absence of divalent cations). Grey bars: Binding in the presence of excess c[RGDfV] peptide. Data represent the mean of independent experiments. Error bars = 1 sd.

* Total binding > VLO4, kistrin, echistatin, bitistatin, c[RGDyK] (P<0.05)

** Total binding > echistatin, bitistatin, c[RGDyK] (P<0.05)

*** Total binding > bitistatin (P<0.05)

**** Total binding > c[RGDyK] (P<0.05)

Competition for binding to αvβ3

In the cell binding assays, addition of excess peptide c[RGDfV] competed with binding to various degrees, depending on the disintegrin used (Figures 1–3 and Table 2). In HUVEC, 100% of 99mTc-echistatin binding was abolished in the presence of 10 μM c[RGDfV], but only 42% of 99mTc-flavoridin binding was abolished. The binding of 99mTc-VLO4 to HUVEC was reduced only 17% by competing peptide; when these studies were repeated in MVEC cells, 99mTc-VLO4 had 40% reduction in binding by competing peptide. On MDA-MB-435S cancer cells, binding of 99mTc-bitistatin, echistatin, flavoridin and kistrin was reduced extensively (>80%) in the presence of c[RGDfV], whereas binding of 99mTc-VLO4 was reduced only 45%. On SK-MEL-28 cells, the binding of 99mTc-bitistatin and echistatin were reduced extensively (>80%), and binding of other disintegrins was reduced 56–69%. In the presence of excess c[RGDfV], binding of 99mTc-c[RGDyK] was reduced 75%, 72% and 69% in HUVEC, SK-MEL-28 and MDA-MB-435S cells. The disintegrins with the least dependence on αvβ3 seemed to be VLO4, flavoridin, and to a variable extent kistrin; these were the three with the highest binding to cells.

TABLE 2.

Binding of Radiolabeled Disintegrins and Peptide to Cells % of Binding due to αvβ3 (blocked by 10 μM c[RGDfV])

| Cell Line

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radioligand | HUVEC | MVEC | SK-MEL-28 | MDA-MB-435S |

| 99mTc-echistatin | 100% | 81% | 97% | |

| 99mTc-bitistatin | 78% | 93% | 100% | |

| 99mTc-kistrin | 83% | 74% | 69% | 84% |

| 99mTc-flavoridin | 42% | 86% | 56% | 89% |

| 99mTc-VLO4 | 17% | 40% | 69% | 45% |

| 99mTc-c[RGDyK] | 75% | 72% | 69% | |

Internalization after binding

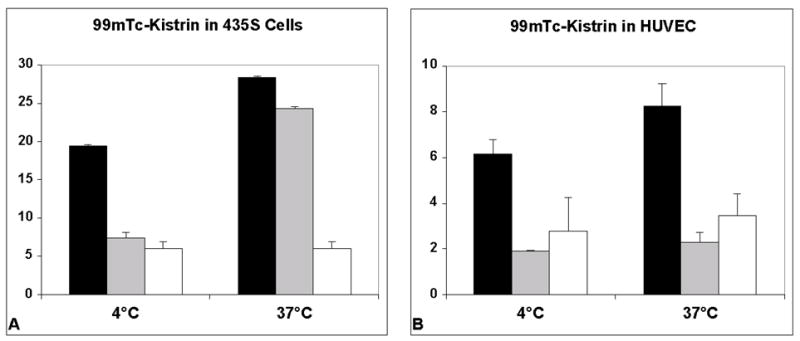

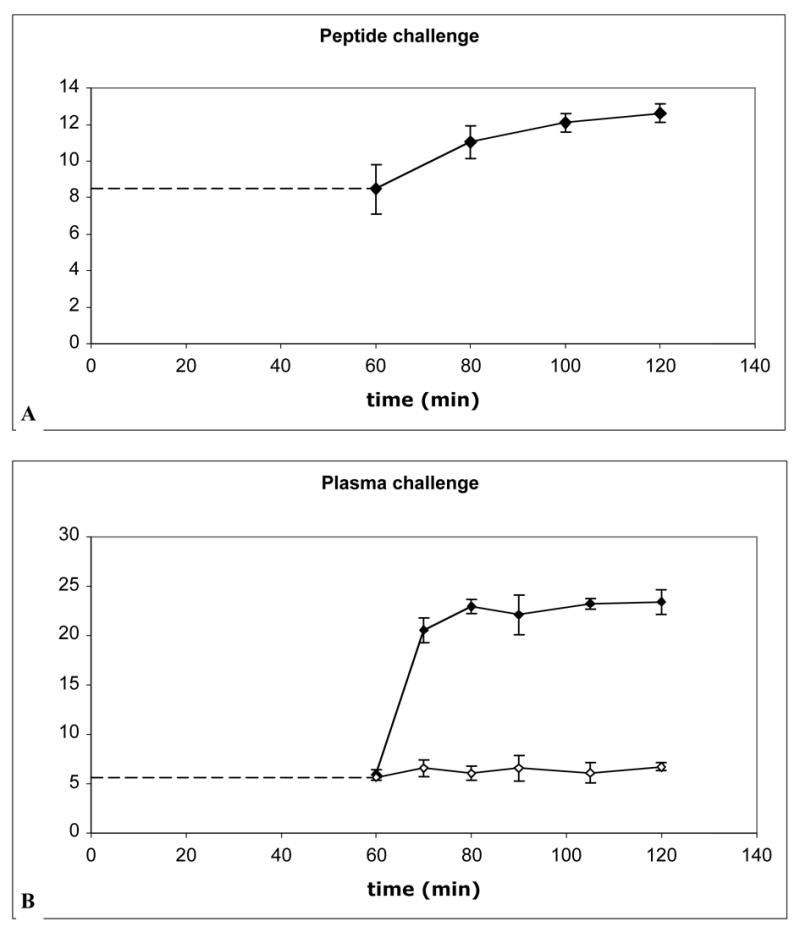

Figure 4A shows an example of an internalization experiment for 99mTc-kistrin binding to MDA-MB-435S cells. At 37°C, 28% of added radioligand bound to cells by 1 hour, of which 6% was nonspecific binding. After cells were exposed to excess EDTA to remove cell-membrane bound activity, the remaining radioactivity (intracellular) was 24%. When the assay was performed at 4°C, 20% bound to cells, but essentially none was internalized: washing removed all radioligand to nonspecific levels. Figure 4B shows that 99mTc-kistrin bound to HUVEC at 4°C and 37°C, but no radiotracer was internalized at either temperature.

Figure 4.

Test of internalization of 99mTc-kistrin by MDA-MB-435S cells and HUVEC. Black bars = total radioligand binding. Gray bars = internalized radioligand. Open bars = nonspecific binding. Data represent the mean of 3 replicates. Error bars = 1 sd.

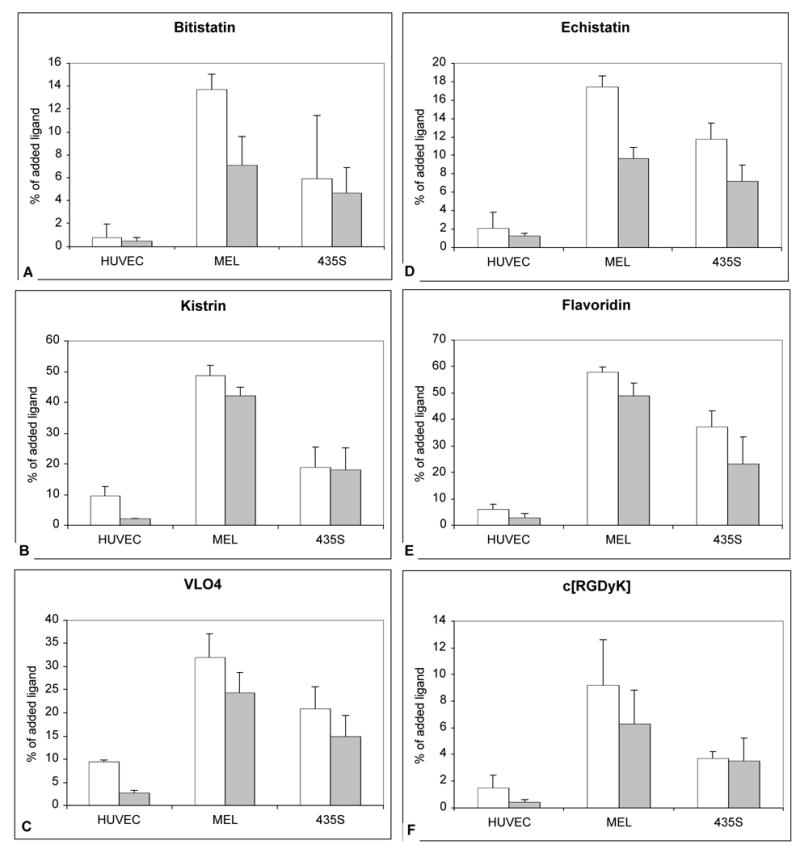

The data for all radioligands and cells are summarized in Figure 5. After binding to SK-MEL-28 and MDA-MB-435S cells for one hour, a substantial fraction (68 – 79%) of 99mTc-VLO4, kistrin and flavoridin was internalized into cells (Figure 5). 99mTc-echistatin, bitistatin and c[RGDyK] were internalized into SK-MEL-28 and MDA-MB-435S cells, but to a lower extent. In contrast, essentially no internalization occurred with HUVEC, and in the case of 99mTc-echistatin, bitistatin and c[RGDyK], the level of internalization was equivalent to nonspecific binding.

Figure 5.

Internalization of bound 99mTc-ligands to cells at 37°C after 1 hour of incubation. Open bars = % of added ligand specifically bound to cells (Total binding – nonspecific binding). Shaded bars = % of added ligand that was internalized. A. 99mTc-bitistatin. B. 99mTc-kistrin. C. 99mTc-VLO4. D. 99mTc-echistatin. E. 99mTc-flavoridin. F. 99mTc-c[RGDyK]. Data represent the mean of independent experiments. Error bars = 1 s.d.

Reversibility of radioligand binding to cell surface

After radiolabeled kistrin had bound to endothelial cells for 1 hour, the binding was challenged with plasma or excess c[RGDfV]. As shown in Figure 6, no displacement of bound radioligand occurred. Instead, addition of excess competing peptide or plasma proteins resulted in an increase in binding of radioligand. No additional radioligand binding occurred in the presence of added buffer.

Figure 6.

Addition of competing ligand causes increased binding, not displacement, of radiolabeled kistrin. After radiolabeled kistrin was allowed to bind to cells for 1 hour at 37°C, excess competing ligand was added and the binding was assessed over the next hour. Binding before addition of competing ligand is represented by dashed line. A. 99mTc-kistrin binding to MVEC, challenged with c[RGDfV] (final concentration 8 μM). B. 125I-kistrin binding to HUVEC, challenged with heparinized plasma (filled diamonds) or binding buffer (open diamonds).

DISCUSSION

The ultimate goal of these studies was to identify one or more disintegrins which could be used as the basis for an in vivo tumor-targeting agent. Such agents could be used for diagnostic imaging with a reporter such as a radionuclide, to map αvβ3 integrins. This technique could be used to select patients for anti-angiogenic therapy and could be used after therapy to assess the success of treatment. Suitable disintegrins could also be used to direct therapeutic agents directly to tumors for targeted therapy.

There has been an interest in small synthetic peptides containing RGD to function as antagonists for integrins. Cyclo[RGDfV], which recognizes αvβ3 and αvβ5 [26], abolished cytokine-induced and tumor-induced angiogenesis and promoted regression of human tumors grown in a chick chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) model [27, 28]. In order to adapt c[RGDfV] for labeling with radioiodine, Haubner et al. synthesized analogues containing D-tyrosine in place of D-phenylalanine: c[RGDyV] [10]. The peptide and its iodinated analogue retained nanomolar affinity for the αvβ3 receptor and were highly selective for αvβ3. Haubner et al also proposed replacing the valine in position 5 with a lysine to provide an amino group for attachment of metal chelators. Such a peptide was synthesized by vanHagen et al, modified with DTPA and labeled with 111In [29]. In tumor-bearing rodents, these labeled cyclic pentapeptides all had rapid blood disappearance. Tumor uptake typically was maximal at the first time point and declined thereafter, suggesting reversible binding.

We hypothesized that disintegrins could provide stronger and more stable binding than cyclic pentapeptides to αvβ3 receptors. These studies confirmed that RGD-containing disintegrins, when labeled with 99mTc via a HYNIC linker, are able to bind to endothelial cells and two types of cancer cells. There was variation in the extent of binding among the different labeled disintegrins. This was expected, based on the variety of disintegrins chosen for study. A cross-section of disintegrins were studied to represent various features of the class of molecules, including small (49 amino acids, aa), medium (68–70 aa) and large (84 aa) monomeric disintegrins, and a dimeric disintegrin (128 aa) (Table 1). They represent several flanking amino acid sequences around -RGD- and various integrin selectivities (Table 3). In previous reports, the amino acid immediately following RGD (in the C-terminal direction) appears to be important for determining specificity for binding to various integrins [30]. Disintegrins containing-RGDW- tend to be more active for blocking fibrinogen binding to αIIbβ3 than for blocking vitronectin binding to αvβ3 [13]. In contrast, disintegrins containing –RGDD- or -RGDN- are more active in blocking vitronectin binding to αvβ3 than in blocking fibrinogen binding to αIIbβ3 [13]. In addition, other portions of the disintegrin molecule, for example the C-terminal portion of echistatin [31], may be important for their integrin selectivity and binding potency. Based on previous reports, echistatin, kistrin and flavoridin were expected to have avid targeting for αvβ3 [11, 12].

TABLE 3.

Previously Reported Inhibitory Activities (IC50) for Disintegrins

| IC50 (nM)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibitor | Fbg/αIIbβ3 | VN/αvβ3 | FN/α5β1 | reference |

| echistatin | 26 | 14 | 11 | [12] |

| 70 | 10 | 1–2 | [39] | |

| bitistatin | 130 | 126 | >1000 | [12] |

| kistrin | <10 | ~10 | 10 | [19, 32, 33] |

| flavoridin | 11 | 8 | 11 | [12] |

| VLO4 | 115 | ND | 3.5 | [22] |

| c[RGDfV] | 35,600 | 82 | 7120 | [12] |

The table includes published results of solid-phase (ELISA) assays of inhibition of native ligand binding to immobilized integrin except: Kistrin (Fbg/αIIbβ3) which was inhibition of 125I-Fbg binding to washed platelets [19] and VLO4 (FN/α5β1) which was inhibition of α5β1-expressing K562 cells binding to immobilized FN and VLO4 (Fbg/αIIbβ3) which was inhibition of αIIbβ3-expressing A5 cells binding to immobilized Fbg [22].

Fbg = fibrinogen; VN = vitronectin; FN = fibronectin. ND = not determined

Kistrin has been shown to have high potency for competing with ligands for αvβ3, but its affinity for α5β1 has been controversial [32, 33]. The limited number of published IC50s suggest that kistrin may have equivalent affinity for αIIbβ3, αvβ3 and α5β1 (Table 3). In the current report, 99mTc-kistrin was among the highest binding ligands for HUVEC, SK-MEL-28 and MDA-MD-435S. A large fraction of 99mTc-kistrin was internalized into SK-MEL-28 and MDA-MD-435S after binding. An average of about three-quarters of the binding of 99mTc-kistrin could be inhibited by competing peptide, suggesting that 99mTc-kistrin binds primarily to αvβ3 on the cells tested.

As a ligand for αvβ3, flavoridin was previously found to exceed the activity of natural protein ligands [12] and was 20–30 times as potent as an anti-αvβ3 monoclonal antibody for inhibiting αvβ3-dependent cell adhesion and migration [34]. Flavoridin has been reported to inhibit αvβ3 and α5β1 about equally [12]. In the present studies, 99mTc-flavoridin had higher binding than other disintegrins to cancer cells, and it was the second highest in binding to HUVEC. Like 99mTc-kistrin, it was internalized into cancer cells to a high extent. However, its binding was not blocked by excess cyclic peptide as extensively, suggesting that it may have bound to another receptor in addition to αvβ3.

The homodimeric disintegrin VLO4 was recently reported as having potent binding to α5β1 [22], with higher affinity than kistrin or flavoridin (see Table 3). Among disintegrins tested in this study, 99mTc-VLO4 had the highest binding to HUVEC and was among the top three in binding to cancer cells. VLO4 recognizes α5β1 > αIIbβ3 > α4β1 on CHO cells transfected with defined integrins, but does not bind to α1β1, α2β1 or α6β1 [22]. Selectivity of VLO4 for αvβ3 has not been reported. In the studies reported here, 99mTc-VLO4 had relatively high binding but especially in endothelial cells the binding seemed to be related to integrins other than αvβ3. It is interesting that VLO4, with a binding loop sequence similar to echistatin, was much more avid than echistatin for binding to cells. This may be related to its larger size (14.2 kDa compared to 5.4 kDa for echistatin). VLO4 is also a homodimer, and thus has two RGD-containing binding domains, which could improve its binding avidity over monomers. In other studies, molecules containing multiple RGD motifs showed higher potency than molecules with single RGD motifs [35].

Since labeled bitistatin had the best biodistribution and pharmacokinetic characteristics in a canine model [16, 36], and since it displayed tumor localization in vivo in previous studies [17], it was evaluated in these studies. Bitistatin is the largest known monomeric disintegrin, and has an additional N-terminal domain [16, 37] that is absent in small and medium-sized monomeric disintegrins. In previous studies, bitistatin displayed only weak activity for inhibiting cell adhesion via αvβ3 (IC50 about 126 nM) [12], so it was not expected to be the best tracer for binding to αvβ3 on cells in vitro. It has been suggested that bitistatin binds to an adhesive protein on endothelial cells which is distinct from a site to which kistrin and echistatin bind [38], and it has been hypothesized that the N-terminal domain of bitistatin is responsible for this interaction with endothelial cells. In the studies reported here, 99mTc-bitistatin had low binding to all cell types. It is not clear what was the target for bitistatin binding in previous studies with tumor-bearing mice [17], but the current findings suggest that other disintegrins may have better uptake in tumors than bitistatin.

In contrast to kistrin and flavoridin binding well as predicted, we observed that echistatin labeled with 99mTc had low to moderate binding to HUVEC and cancer cells. Its binding appeared to be almost completely due to αvβ3, as evidenced by competition with c[RGDfV]. Echistatin is reported to have affinity for α5β1 > αvβ3 > αIIbβ3 (see Table 3) [12, 39]. Echistatin was the smallest disintegrin tested in this report, and its properties may have been more affected by the 99mTc-HYNIC label than were the larger disintegrins. Further studies with echistatin will need to be done to explain this discrepancy.

For comparison with the disintegrins, a synthetic pentapeptide with reported high affinity and integrin selectivity, c[RGDyK], was also radiolabeled and studied. Compared to the disintegrins, the reported affinity for αvβ3 is low (IC50 of 82 nM vs. 8–14 for the most active disintegrins in this study). In these studies, 99mTc-c[RGDfK] had low binding to all cell types. Excess c[RGDfV] peptide was able to only partially (69–75%) abolish binding of 99mTc-c[RGDyK] to HUVEC, SK-MEL-28 and MDA-MD-435S. This may be related to the effects of the HYNIC chelator which was used to enable radiolabeling of the peptide. It has been well-documented that small peptides are easily affected by the size and charge of the radiometal chelating moiety. In addition, the cyclic peptide had a relatively high level of nonspecific binding compared to its total binding.

The possibility that the HYNIC modification altered the binding characteristics of the disintegrins must be considered. The presence of a HYNIC moiety is unlikely to change the overall charge on the peptide, but if it is located in proximity to the RGD binding domain, it could affect the orientation of the binding domain and possibly its binding affinity and selectivity. Studies have suggested that the shape/orientation of the RGD binding domain in various molecules determine their selectivity for αIIbβ3 and αvβ3 [30, 31]. In this study, bitistatin and kistrin were modified with an average of about 2 HYNIC per molecule, while echistatin, flavoridin and VLO4 were modified with about 1 HYNIC per molecule. These differences alone do not appear to explain the observed differences in binding, because kistrin bound well while bitistatin bound poorly, and the remaining disintegrins also had a mixture of binding abilities. Flavoridin (modified with 1 HYNIC group) is very close in size to kistrin (2 HYNIC groups): it does not appear that there was a major difference in binding between these two. A more important aspect of HYNIC modification of disintegrins may be the location of the modified lysine residue relative to the RGD binding domain. The disintegrins tested have either 4 or 5 lysine residues per polypeptide chain. Molecular models, which are available in public databases (such as GenBank) for echistatin, kistrin, flavoridin and bitistatin, reveal some differences in the positioning of lysines in these highly folded molecules. In kistrin and flavoridin, all the lysines and the amino terminus are located on the opposite end of the molecule from the RGD binding domain (data not shown). In contrast, Lys21 and Lys45 in echistatin appear to be near enough to the RGD domain to cause an effect if they were to be modified with a HYNIC moiety (data not shown). It is possible that the unexpectedly poor binding observed with 99mTc-HYNIC-echistatin was related to placement of HYNIC near the binding domain. Modeling of bitistatin has shown that placement of 99mTc-tricine-HYNIC at Lys36 of bitistatin would be expected to result in poorer binding than placement at other lysine positions, and mutation of Lys36 to prevent attachment of HYNIC there was shown to improve bioactivity [40]. A molecular model for VLO4 is not yet available, however it seems that placement of one HYNIC moiety on this dimeric molecule would at worst leave one half of the molecule available to bind to its receptor.

The data in this study suggest that tumor cells SK-MEL-28 and MDA-MB-435S internalize radiolabeled disintegrins after binding. Receptor-mediated endocytosis can be very important in tumor targeting for purposes of diagnostic imaging or radiotherapy, as it would enable bound radioligand to remain in the tumor longer without washout and achieve higher target-to-background ratios. In contrast, the data for HUVEC suggest that radiolabeled disintegrins and c[RGDyK] may not be internalized after binding to endothelial cells. The macromolecular ligands which bind to integrins αIIbβ3, αvβ3, and α5β1 are cell adhesion molecules. It is not clear what functional purpose would be served by endocytosis after receptor binding. In the case of targeting purely vascular αvβ3 integrins in angiogenesis, radiotracers need to bind strongly to surface receptors to avoid displacement by endogenous ligands in blood. Disintegrins such as kistrin, which binds strongly without reversibility may have an advantage in this case. The binding of radiolabeled VL04 to endothelial cells was also nonreversible upon plasma challenge (data not shown).

Disintegrins may offer some advantages over small cyclic peptides for targeting tumor angiogenesis. First, small peptides tend to have lipophilic character as a consequence of keeping them small. Native peptides such as disintegrins are very water-soluble because they are highly folded, with lipophilic residues on the inside and hydrophilic residues on the outside. Second, small RGD containing peptides typically have achieved moderate target-to-background ratios, with a low percentage of injected dose per gram tumor. This may be because rapid blood disappearance minimizes delivery of radioligand to the target tissue, or because the radioligand is not retained well in target tissue after binding. The slightly slower blood clearance rates of the disintegrins might increase bioavailability and the percent of dose which is able to bind to a lesion. Third, the small synthetic peptides have very simple structure, implying a simple interaction with a receptor which evolved to bind complex macromolecules with multiple domains. In addition to the RGD-containing loop, other domains of some disintegrins may be involved in integrin selectivity and potency, perhaps by stabilizing the interaction between the disintegrin and the receptor by binding at multiple sites [31, 41]. There may be an advantage to using targeting molecules which can interact more fully with the receptor. This could lead to increased duration of binding by surface receptors on endothelial cells, since the receptor-bound ligand does not appear to be internalized.

Studies with labeled kistrin indicated that radioligand bound to the surface of endothelial cells is not displaced by competing c[RGDfV] or plasma proteins. It was an unexpected finding that addition of competing ligands caused increased binding of radiolabeled kistrin. It is possible that this phenomenon was related to an interaction between kistrin and α5β1, which is highly expressed on endothelial cells. Studies from our lab and that of others [42] have shown that kistrin does not inhibit binding of fibronectin to K562 cells that selectively express α5β1. However, K562 cells strongly adhere to kistrin, suggesting that kistrin does interact with α5β1, but kistrin and fibronectin may bind to a different epitopes on α5β1. The addition of plasma proteins or cyclic RGD peptides to endothelial cells cause blocking of the interaction of kistrin with αvβ3 integrin, but not with α5β1. In addition, binding of ligands to αvβ3 may modulate (increase) the activity of α5β1 following “cross-talk” between integrins, resulting in higher binding of kistrin to α5β1. The “cross-talk” between αvβ3 and α5β1 has been previously reported [43].

In conclusion, 99mTc-labeled flavoridin, kistrin and VLO4 had higher cell binding than echistatin, bitistatin or c[RGDyK]. This suggests they may have better tumor targeting in vivo, so they should be the best candidates for further testing.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA96792) and the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (R01 HL54578). We would like to thank Kwamena Baidoo, PhD, for synthesizing succinimidyl-hydrazinonicotinamide, and Mical Samuelson for assistance with binding assays.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Felding-Habermann B, Cheresh DA. Vitronectin and its receptors. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 1993;5:864–868. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(93)90036-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suehiro K, Smith JW, Plow EF. The ligand recognition specificity of β3 integrins. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:10365–10371. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.17.10365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shattil SJ. Function and regulation of the β3 integrins in hemostasis and vascular biology. Thromb Haemost. 1995;74:149–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brooks PC, Cheresh DA, Clark AF. Requirement of vascular integrin alpha v beta 3 for angiogenesis. Science. 1994;264:569–571. doi: 10.1126/science.7512751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cox D, Aoki T, Seki J, Motoyama Y, Yoshida K. The pharmacology of the integrins. Medicinal Research Reviews. 1994;14:195–228. doi: 10.1002/med.2610140203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Albelda SM, Mette SA, Elder DE, et al. Integrin distribution in malignant melanoma: Association of the beta(3) subunit with tumor progression. Cancer Research. 1990;50:6757–6764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gladson CL, Cheresh DA. Glioblastoma expression of vitronectin and the alpha(v)beta(3) integrin. Adhesion mechanism for transformed glial cells. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:1924–1932. doi: 10.1172/JCI115516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beauvais DM, Burbach BJ, Rapraeger AC. The syndecan-1 ectodomain regulates avb3 integrin activity in human mammary carcinoma cells. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:171–181. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200404171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheresh DA, Spiro RC. Biosynthetic and functional properties of an Arg-Gly-Asp-directed receptor involved in human melanoma cell attachment to vitronectin, fibronectin, and von Willebrand factor. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:17703–17711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haubner R, Wester H-J, Reuning U, et al. Radiolabeled αvβ3 integrin antagonists: A new class of tracers for tumor targeting. J Nucl Med. 1999;40:1061–1071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Juliano D, Wang Y, Marcinkiewicz C, Rosenthal LA, Stewart GJ, Niewiarowski S. Disintegrin interaction with alpha V beta 3 integrin on human umbilical vein endothelial cells: Expression of ligand-induced binding site on beta 3 subunit. Experimental Cell Research. 1996;225:132–142. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.0164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pfaff M, McLane MA, Beviglia L, Niewiarowski S, Timpl R. Comparison of disintegrins with limited variation in the RGD loop in their binding to purified integrins alphaIIb beta3, alphaV beta3 and alpha5 beta1 and in cell adhesion inhibition. Cell Adhesion and Communication. 1994;2:491–501. doi: 10.3109/15419069409014213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scarborough RM, Rose JW, McNaughton MA, et al. Characterization of the integrin specificities of disintegrins isolated from American pit viper venoms. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:1058–1065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gould RJ, Polokoff MA, Friedman PA, et al. Disintegrins: A famity of integrin inhibitory proteins from viper venoms. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1990;195:168–171. doi: 10.3181/00379727-195-43129b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niewiarowski S, McLane MA, Kloczewiak M, Stewart GJ. Disintegrins and other naturally occurring antagonists of platelet fibrinogen receptors. Semin Hematol. 1994;31:289–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knight LC, Baidoo KE, Romano JE, Gabriel JL, Maurer AH. Imaging pulmonary emboli and deep venous thrombi with 99mTc-labeled bitistatin, a platelet-binding polypeptide from viper venom. J Nucl Med. 2000;41:1056–1064. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McQuade P, Knight LC, Welch MJ. Evaluation of 64Cu and 125I-Radiolabeled Bitistatin as Potential Agents for Targeting αvβ3 Integrins in Tumor Angiogenesis. Bioconjugate Chem. 2004;15:988–996. doi: 10.1021/bc049961j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knight LC, Romano JE. Functional expression of bitistatin, a disintegrin with potential use in molecular imaging of thromboembolic disease. Protein Expression and Purification. 2005;39:307–319. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dennis MS, Henzel WJ, Pitti RM, et al. Platelet glycoprotein IIb-IIIa protein antagonists from snake venoms: Evidence for a family of platelet-aggregation inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;87:2471–2475. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.7.2471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gan ZR, Gould RJ, Jacobs JW, Friedman PA, Polokoff MA. Echistatin: A potent platelet aggregation inhibitor from the venom of the viper, Echis carinatus. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:19827–19832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calvete JJ, Wang Y, Mann K, Schafer W, Niewiarowski S, Stewart GJ. The disulfide bridge pattern of snake venom disintegrins, flavoridin and echistatin. FEBS Lett. 1992;309:316–320. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80797-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calvete JJ, Moreno-Murciano MP, Theakston RDG, Kisiel DG, Marcinkiewicz C. Snake venom disintegrins: novel dimeric disintegrins and structural diversification by disulphide bond engineering. Biochem J. 2003;372:725–734. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abrams MJ, Juweid M, tenKate CI, et al. Technetium-99m-human polyclonal IgG radiolabeled with the hydrazino nicotinamide derivative for imaging focal sites of infection in rats. J Nucl Med. 1990;31:2022–2028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.King T, Zhao S, Lan T. Preparation of protein conjugates via intermolecular hydrazone linkage. Biochemistry. 1986;25:5774–5779. doi: 10.1021/bi00367a064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larsen SK, Solomon HF, Caldwell G, Abrams MJ. [99mTc]tricine: a useful precursor complex for the radiolabeling of hydrazinonicotinate protein conjugates. Bioconjugate Chem. 1995;6:635–638. doi: 10.1021/bc00035a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pfaff M, Tangemann K, Müller B, et al. Selective recognition of cyclic RGD peptides of NMR defined conformation by aIIbb3, avb3 and a5b1 integrins. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:20233–20238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brassard D, Maxwell E, Malkowski M, Nagabhushan T, Kumar C, Armstrong L. Integrin alphavbeta3-mediated activation of apoptosis. Experimental Cell Research. 1999:33–45. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Friedlander M, Brooks PC, Shaffer RW, Kincaid CM, Varner JA, Cheresh DA. Definition of two angiogenic pathways by distinct av integrins. Science. 1995;270:1500–1502. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5241.1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Hagen PM, Breeman WAP, Bernard HF, Schaar M, Krenning EP, de Jong M. Evaluation of a radiolabelled cyclic DTPA-RGD analogue for tumour imaging and radionuclide therapy. Int J Cancer. 2000;8:186–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McLane MA, Vijay-Kumar S, Marcinkiewicz C, Calvete JJ, Niewiarowski S. Importance of the structure of the RGD-containing loop in the disintegrins echistatin and eristostatin for recognition of alpha IIb beta 3 and alpha v beta 3 integrins. FEBS Lett. 1996;391:139–143. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00716-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wierzbicka-Patynowski I, Niewiarowski S, Marcinkiewicz C, Calvete JJ, Marcinkiewicz MM, McLane MA. Structural requirements of echistatin for the recognition of avb3 and a5b1 integrins. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:37809–37814. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.53.37809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones JI, Prevette T, Gockerman A, Clemmons DR. Ligand occupancy of the avb3 integrin is necessary for smooth muscle cells to migrate in response to insulin-like growth factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2482–2487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.6.2482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tselepis V, Green LJ, Humphries MJ. An RGD to LDV motif conversion within the disintegrin kistrin generates an integrin antagonist that retains potency but exhibits altered receptor specificity. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:21341–21348. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.34.21341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sheu J-R, Yen M-H, Kan Y-C, Hung W-C, Chang P-T, Luk H-N. Inhibition of angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo: comparison of the relative activities of triflavin, an Arg-Gly-Asp-containing peptide and anti-avb3 integrin monoclonal antibody. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1997;1336:445–454. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(97)00057-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kok RJ, Schraa AJ, Bos EJ, et al. Prepararation and functional evaluation of RGD-modified proteins as αvβ3 integrin directed therapeutics. Bioconjugate Chem. 2002;13:128–135. doi: 10.1021/bc015561+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Knight LC, Maurer AH, Romano JE. Comparison of Iodine-123-disintegrins for imaging thrombi and emboli in a canine model. J Nucl Med. 1996;37:476–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Calvete J, Schrader M, Raida M, McLane MA, Romero A, Niewiarowski S. The disulphide bond pattern of bitistatin, a disintegrin isolated from the venom of the viper Bitis arietans. FEBS Lett. 1997;416:197–202. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01203-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McLane MA, Marcinkiewicz C, Vijay-Kumar S, Wierzbicka-Patynowski I, Niewiarowski S. Viper venom disintegrins and related molecules. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1998;219:109–119. doi: 10.3181/00379727-219-44322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scarborough RM, Rose JW, Hsu MA, Phillips DR, Fried VA, Campbell AM, Nannizzi L, Charo IF. Barbourin. A GPIIb-IIIa-specific integrin antagonist from the venom of Sistrurusm. barbouri. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:9359–9362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Knight LC, Romano JE, Gabriel JL. Selection of radiolabeling sites by site-directed mutagenesis. J Labelled Comp Radiopharm. 2003;46:S24. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marcinkiewicz C, Vijay-Kumar S, McLane MA, Niewiarowski S. Significance of RGD loop and C-terminal domain of echistatin for recognition of aIIbb3 and avb3 integrins and expression of ligand-induced binding site. Blood. 1997;90:1565–1575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rahman S, Aitken A, Flynn G, Formstone C, Savidge GF. Modulation of RGD sequece motifs regulates disintegrin recognition of αIIbβ3 and α5β1 integrin complexes. Biochem J. 1998;335:247–257. doi: 10.1042/bj3350247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ly DP, Zazzali KM, Corbett SA. De novo expression of the integrin α5β1 regulates αvβ3-mediated adhesion and migration on fibrinogen. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:21878–21885. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212538200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]