Abstract

Diverse physiological actions of growth hormone (GH) are mediated by changes in gene transcription. Transcription can be regulated at several levels, including post-translational modification of transcription factors, and formation of multiprotein complexes involving transcription factors, co-regulators and additional nuclear proteins; these serve as targets for regulation by hormones and signaling pathways. Evidence that GH regulates transcription at multiple levels is exemplified by analysis of the proto-oncogene c-fos. Among the GH-regulated transcription factors on c-fos, C/EBPβ appears to be key, since depletion of C/EBPβ by RNA interference blocks the stimulation of c-fos by GH. The phosphorylation state of C/EBPβ and its ability to activate transcription are regulated by GH through MAPK and PI3K/Akt-mediated signaling cascades. The acetylation of C/EBPβ also contributes to its ability to activate c-fos transcription. These and other post-translational modifications of C/EBPβ appear to be integrated for regulation of transcription by GH. The formation of nuclear proteins into complexes associated with DNA-bound transcription factors is also regulated by GH. Both C/EBPβ and the co-activator p300 are recruited to c-fos in response to GH, altering c-fos promoter activation. In addition, GH rapidly induces spatio-temporal relocalization of C/EBPβ within the nucleus. Thus, GH-regulated gene transcription mediated by C/EBPβ reflects the integration of diverse mechanisms including post-translational modifications, modulation of protein complexes associated with DNA and relocalization of gene regulatory proteins. Similar integration involving other transcription factors, including Stats, appears to be a feature of regulation by GH of other gene targets.

Keywords: C/EBPβ, c-fos, phosphorylation, acetylation, co-activator complex, p300, heterochromatin, Stats

Introduction

Pituitary Growth Hormone (GH) has long been known as a major regulator of normal growth and metabolism (1-3). Among its diverse actions, GH promotes statural growth in conjunction with Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 (IGF-1) by stimulating chondrocytes in long bones (4-7). GH promotes a relative increase in lean body mass and decrease in body lipid, reflecting changes that include the ability of GH to increase cellular protein synthesis, stimulate lipolysis and impair lipogenesis under physiological conditions (8, 9). GH excess can result in acromegaly and insulin resistance (8, 10, 11).

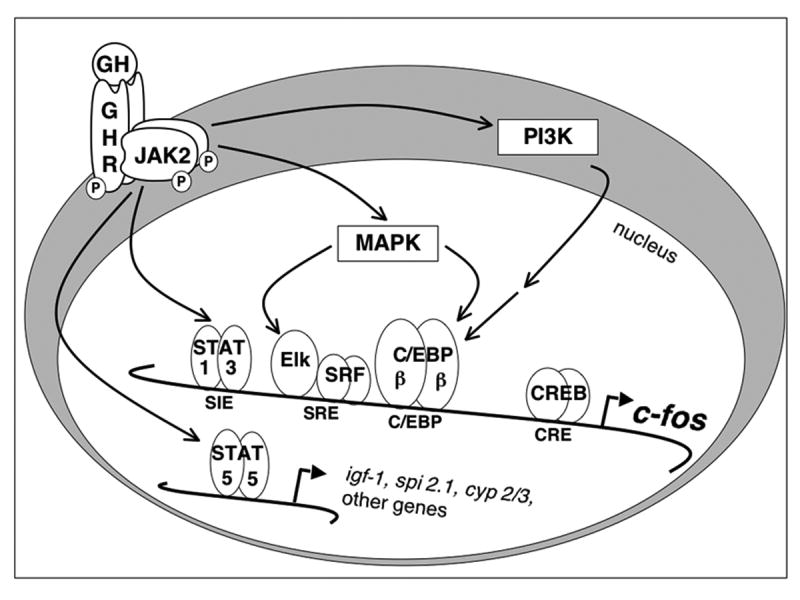

GH-regulated gene transcription underlies many of the diverse responses to GH (Fig 1). These responses are initiated by the interaction of GH with the GH receptor, a member of the cytokine receptor superfamily (12, 13). Janus kinase 2 (JAK2), a non-receptor tyrosine kinase, associates with dimerized GH receptors (14). The activated JAK2 phosphorylates itself and the cytoplasmic domain of the GH receptor to initiate downstream signaling. Cytoplasmic signaling molecules, including Signal Transducers and Activators of Transcription (Stats), pathways mediated by Mitogen Activated Protein Kinases (MAPK), and Phosphatidy Inositol 3′ Kinase (PI3K), relay GH signals to the nuclei of target cells to modulate gene transcription (12, 13, 15, 16).

Figure 1. GH signaling to the nucleus.

A model of GH-regulated signaling pathways, and transcription factors that they regulate on representative genes, is shown. The interaction of GH with GH receptors (GHR) leads to association and activation of JAK2, initiating signaling cascades such as those mediated by STATS, MAPK and PI3K. These signaling pathways culminate in the regulation of multiple transcription factors on GH target genes, as described in text.

Changes in gene transcription in response to GH occur at multiple levels, including post-translational modifications of nuclear proteins, formation of nucleoprotein complexes and cellular relocalization of factors that regulate transcription. While some aspects of these events have been analyzed for the Signal Transducers and Activators of Transcription (Stats), this review focuses on regulation of CCAAT/Enhancer Binding Protein β (C/EBPβ), a transcription factor essential for GH-stimulated c-fos expression and serves to illustrate the complexity in the diverse mechanisms of gene regulation by GH.

GH regulates transcription by modifying the activity of multiple transcription factors

As part of the mechanism of gene regulation by GH, it has been amply demonstrated that Stat family members, especially Stat 5a and 5b, mediate the GH-dependent activation of a number of genes (15). Interaction of GH with its receptors activates the tyrosine kinase Jak2, which phosphorylates and activates cytoplasmic Stats 1, 3, and 5. Phosphorylated Stats translocate to the nucleus and bind to DNA elements within GH target genes (17). Stat 5b has been implicated in the transcription of multiple GH-regulated genes, and in GH-promoted growth in vivo (18, 19). The gene for IGF-1, has recently been shown to be regulated by Stat 5 in response to GH (20-25). In the case of the gene for the liver-specific serine protease inhibitor 2.1 (Spi 2.1), a component of acute phase responses (26), GH regulates transcription through an upstream regulatory region containing a GH response element (GHRE) which binds Stat 5 at several Gamma-interferon Activated Sequence (GAS)-Like Elements (GLE) (27-29). Studies of the genes encoding members of the cytochrome P450 (cyp) 2 and 3 families involved in steroid metabolism demonstrate that sexually dimorphic GH secretory patterns in male and female murine models differentially regulate gene expression through a mechanism mediated by transcription factors Stat 5b and Hepatic Nuclear Factor (HNF) 4α (30-32).

Although Stat 5a and 5b mediate transcription of these and other GH-regulated genes, it is well recognized that overall transcription is dependent on the coordination of multiple transcription factors and other nuclear proteins. Some of these factors and events have been elucidated by analysis of the proto-oncogene c-fos. This ubiquitous early response gene associated with cell growth is rapidly and transiently induced by GH (33, 34). Analyses of the c-fos enhancer region have identified multiple transcription factors regulated by GH through multiple signaling pathways (16) (Figure 1). These transcription factors include Stats 1 and 3, which are induced to bind to the Sis-Inducible Element (SIE) in response to GH (35-38). Serum Response Factor (SRF) and Ternary Complex Factor (TCF) family members such as Elk-1 bind to the Serum Response Element (SRE) and also mediate c-fos transcription in response to GH (39, 40). The c-fos C/EBP site, which binds the transcription factors C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ, is also regulated by GH (16). Further, since the c-fos enhancer also contains an AP-1 site, it is of interest that GH also induces binding of Fos and Jun family proteins to this element (41-43). Deletion analysis of the c-fos promoter suggests that each of these transcription factor binding sites contributes to GH-regulated c-fos promoter activation (44). GH also appears to stimulate phosphorylation of the Cyclic AMP Response Element Binding Protein (CREB) (45) (Cui and Schwartz, submitted), which can mediate c-fos transcription through a proximal CRE (46, 47).

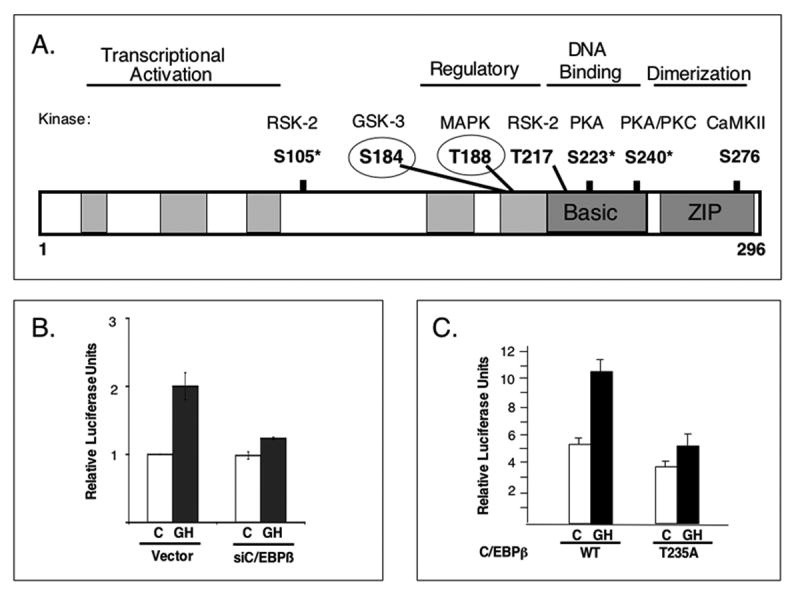

A critical role for the transcription activator C/EBPβ (Fig 2A) in c-fos promoter activation by GH was demonstrated by loss of function experiments. Expression of a short hairpin RNA targeting C/EBPβ (siC/EBPβ) reduced endogenous C/EBPβ levels via RNA interference (RNAi) (Fig. 2B) (48). This manipulation abolished the ability of GH to mediate c-fos promoter activation and expression of endogenous c-fos mRNA (48). These findings indicate that cellular C/EBPβ plays a critical role in the ability of GH to stimulate c-fos transcription. Complementary experiments in primary murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) from mice with a targeted deficiency of C/EBPβ (49, 50) revealed that the absence of C/EBPβ impaired GH-stimulated c-fos promoter activity (51) and established that endogenous C/EBPβ is necessary for full activation of the c-fos promoter by GH. Understanding the mechanisms by which hormones such as GH regulate C/EBPβ function is of broader interest since in addition to its role in GH regulation of c-fos transcription, this widely distributed transcription factor interacts with a variety of nuclear proteins (52-55), and is a key regulator of multiple developmental programs such as adipocyte differentiation (56). This role of C/EBPβ is pertinent in the case of GH, since differentiation of 3T3-F442A preadipocytes, one of the most sensitive in vitro models for studying GH action, is dependent on GH (6).

Figure 2. C/EBPβ is regulated by GH.

A. C/EBPβ is modified post-translationally at multiple sites. The C/EBPβ diagram shows approximate regions encompassing the transcriptional activation domain, regulatory domain, the DNA binding basic region as well as the leucine zipper dimerization domain. Multiple phosphorylation sites are indicated (numbering for murine sequence) and the corresponding kinases are shown above. Circled residues are GH-regulated. B. Activation of c-fos by GH depends on endogenous C/EBPβ. Endogenous C/EBPβ was depleted by RNA interference through expression of siC/EBPβ, in CHO cells stably expressing a GH receptor that mediates c-fos activation (CHO-GHR). In cells expressing vector, the typical effect of GH to activate the c-fos promoter is seen as an increase in luciferase expression (relative luciferase units). In cells depleted of C/EBPβ by expression of siC/EBPβ, GH fails to activate the c-fos promoter, demonstrating that endogenous C/EBPβ is necessary for the response to GH (48). C. Phosphorylation of C/EBPβ at a MAPK substrate site is critical for GH-stimulated c-fos promoter activation. GH stimulates the c-fos promoter when native (WT) human C/EBPβ is expressed in CHO-GHR cells, but expression of C/EBPβ with a mutation at a MAPK substrate site (T235) blunts the GH response (57). Responses to GH are shown as mean ± se for at least 3 experiments.

GH regulates transcription factors through a variety of post-translational modifications

The demonstration that GH activates Stats by stimulating their tyrosine phosphorylation was a landmark in understanding GH signaling (35, 36, 38). The importance of other signaling events in GH-stimulated transcription is demonstrated by observations of GH-regulated changes in the phosphorylation state of C/EBPβ (Fig 2A). Isoelectric focusing identified at least six different phosphorylated forms of C/EBPβ that are regulated by GH in 3T3-F442A cells (57). A MAPK substrate site at T235 in human C/EBPβ (which corresponds to T188 in murine C/EBPβ) is rapidly and transiently phosphorylated in response to GH in an ERK 1/2 dependent manner (57). Mutation at that MAPK phosphorylation site of C/EBPβ almost completely abrogates the stimulation of c-fos in response to GH (Fig 2C), indicating that phosphorylation at the MAPK substrate site is required for GH to activate the c-fos promoter. It is notable that while phosphorylation of C/EBPβ at T188 is rapid and transient, dephosphorylation of C/EBPβ at a glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK-3) substrate site, S184 (58) occurs only after 60 minutes. The delayed dephosphorylation may be related to attenuation of c-fos transcription and is dependent on activation by GH of PI-3K and Akt, which leads to inhibition of GSK-3 activity. Thus, regulation by GH of the phosphorylation state of C/EBPβ mediated by MAPK and PI-3K-Akt signaling cascades is an important component of the mechanisms of GH-stimulated transcription.

In addition to phosphorylation, a growing list of modifications, including acetylation, methylation, ubiquitination and SUMOylation, regulate the transcriptional regulatory potential of multiple nuclear proteins (59). In the case of histones, combinations of such modifications are now recognized to serve as a “histone code” written, interpreted and erased by a complex machinery (60). The acetylation state of nuclear proteins is highly susceptible to regulation by histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and/or histone deacetylases (HDACs). C/EBPβ interacts with both p300 and CREB Binding Protein (CBP) (54, 61) which are nuclear co-activators with HAT activity. p300 and CBP, homologous factors identified through their respective associations with CREB and the viral protein E1A (62-64), were among the first co-activators characterized. The C/EBPβ sequence contains 21 lysines, and among these K39 was found to be acetylated by p300 (Cesena T.I., Kwok RK, Schwartz J, submitted). Mutation of C/EBPβ at K39, which is in the transcription activation domain, leads to reduction in its acetylation as detected by immunoblotting with anti-acetyl-lysine antibody and reduces its ability to activate transcription of a variety of promoters, including c-fos. Further, GH-stimulated c-fos transcription is also impaired by mutation of C/EBPβ at K39 (Cesena et al., submitted), suggesting that acetylation of C/EBPβ at K39 facilitates its ability to activate transcription in response to GH. In addition to activating transcription by stimulating HATS, inhibiting HDACs to maintain acetylation can also enhance c-fos transcription (65). Since some HDACs occupy the c-fos promoter in a GH-dependent manner (Cui and Schwartz, unpublished), regulation of HDACs in transcription complexes may be part of the mechanism by which GH regulates c-fos transcription. SUMOylation is a post-translational modification which is often associated with negative regulation of transcription (66)(67). SUMOylation involves the conjugation of members of the Small Ubiquitin-Like MOdifier (SUMO) family to acceptor lysine residues in target proteins (68). Interestingly, lysine 133 in murine C/EBPβ is SUMOylated (69-71). Mutation of C/EBPβ at K133 elevates basal c-fos transcription to a level where it cannot be further stimulated by GH (71), opening the possibility that desumoylation, and consequent relief of an inhibitory effect of SUMO, may contribute to the ability of C/EBPβ to activate transcription in response to GH. The combined influence of multiple post-translational modifications regulated by GH on C/EBPβ, and possibly other GH-regulated transcription factors, is likely to be a key factor in the coordinated, moment-to-moment regulation of gene transcription by GH.

GH regulates the composition of nucleoprotein complexes that mediate gene transcription

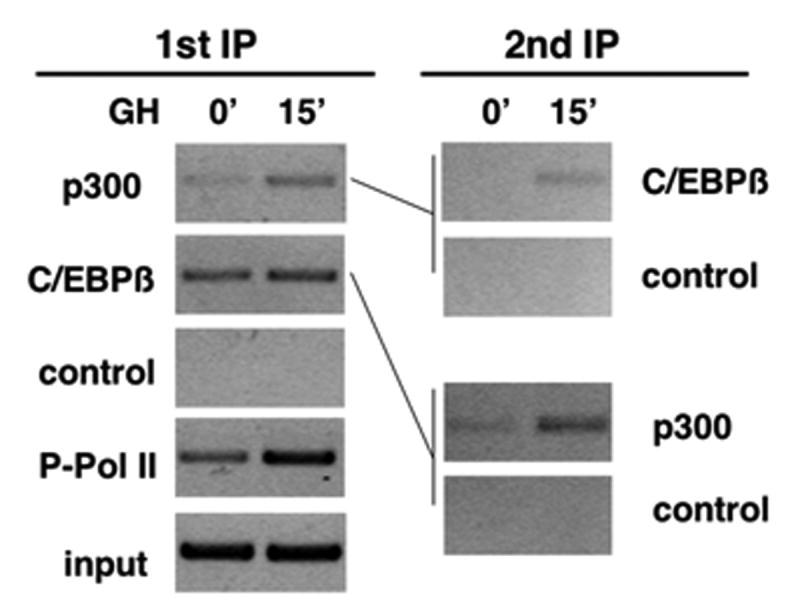

Our current understanding of transcription supports a mechanism in which binding of regulated sequence-specific transcription factors, such as the GH-regulated Stats and C/EBPβ, to their cognate response elements, provides a platform for formation of multiprotein complexes. The complexes often include factors such as co-activators, co-repressors, HATS, HDACs, chromatin remodeling factors and other proteins, which communicate signals from regulated factors to the general transcription machinery (72). Some of these nucleoproteins associate via protein-protein interactions with individual transcription factors bound to DNA at regulated enhancer sequences (73-76). Although co-activators may contain intrinsic HAT activity or recruit HAT activity and co-repressors often associate with HDACs, these and many other co-regulators mediate diverse positive and negative events (77, 78). C/EBPβ as well as Stat 5b have been reported to interact with p300/CBP (54, 61, 79), suggesting that formation of transcription complexes may be another mechanism by which GH regulates transcription. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments, which analyze the occupancy of endogenous proteins on promoter DNA in vivo, support this model since GH rapidly increases the occupancy of endogenous C/EBPβ on the c-fos promoter in 3T3-F442A cells (Fig 3) (48). ChIP also reveals that the occupancy of p300 on c-fos increases rapidly and transiently with GH treatment. The GH-induced increase in occupancy of p300 is striking because it coincides with the transient increase in c-fos transcription induced by GH (33), and is paralleled by a GH-induced increase in occupancy of phosphorylated RNA polymerase II (Pol II), an indicator of activated transcription. In support of their participation in a complex in response to GH, C/EBPβ and p300 were found to co-occupy the c-fos promoter following GH treatment. These re-ChIP experiments (Fig 3) suggest the presence of a complex containing both C/EBPβ and p300 on the c-fos promoter in response to GH. The increase in occupancy is accompanied by a synergistic increase in c-fos promoter activation when C/EBPβ and p300 are co-expressed (48). By determining the baseline transcription, the presence of p300 appears to dictate the extent to which GH stimulates c-fos expression. The activity of GH–induced complexes is likely to be coordinated with other GH-regulated events including post-translational modifications. For example, the occupancy of the phosphorylated form of C/EBPβ is rapidly and transiently increased on the c-fos promoter in response to GH (48) and was blocked by inhibition of ERKs 1 and 2 (Cui and Schwartz, submitted). It will be of interest to determine whether phosphorylated C/EBPβ is newly recruited to the promoter in response to GH, or whether C/EBPβ constitutively occupying c-fos becomes phosphorylated in situ in response to GH. In either case, it is likely that phosphorylation of C/EBPβ is part of the regulatory mechanisms that direct recruitment of co-regulatory proteins such as p300 to the c-fos promoter in response to GH. Similar mechanisms may contribute to the recruitment of other factors to this and other GH-regulated genes (80). Taken together, these findings indicate that GH dynamically regulates the composition of complexes that assemble at the promoters of GH-regulated genes.

Figure 3. GH promotes the occupancy of a complex containing both C/EBPβ and p300 at the c-fos promoter.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was performed using 3T3-F442A fibroblasts, which respond to GH via endogenous GH receptors. ChIP indicates that endogenous C/EBPβ and p300 are rapidly recruited to the c-fos promoter in response to GH in vivo (1st IP). Both proteins occupy the same c-fos DNA, as demonstrated by second ChIP (48).

GH regulates the cellular localization of transcription factors

The cellular localization of gene regulatory proteins is an important determinant of transcription. It is well established that activation of Stats 1, 3 and 5 by GH is accompanied by their translocation from the cytoplasm to nucleus, where they activate target genes (15). In the case of C/EBPβ, its sub-nuclear localization appears to be a regulated event (81). Immunofluorescence analysis of the nuclear localization of C/EBPβ revealed that GH dramatically shifts the distribution of C/EBPβ within the nucleus (82). In resting cells, C/EBPβ is diffusely distributed in the nucleus, but within 5 min of GH treatment C/EBPβ acquires a distinct punctate distribution that corresponds to heterochromatin, since it co-localizes with heterochromatin protein 1α. Interestingly, C/EBPβ phosphorylated at the MAPK substrate site was detected in heterochromatin rapidly and transiently after GH treatment. This rapid GH-dependent re-localization was prevented when MAPK signaling was blocked, suggesting that re-localization is triggered by activation of MAPK in response to GH. The significance of re-localization of C/EBPβ to heterochromatin is not clear, although one can speculate that it may involve an endogenous truncated form of C/EBPβ (LIP), which contains a MAPK substrate site but lacks the transcriptional activation domain, and inhibits transcription. Regulation of the distribution of C/EBPβ in the nucleus demonstrates a novel spatio-temporal level of regulation by GH, which appears to be coordinated with a GH-induced post-translational modification of the transcription factor.

GH regulates transcription by multiple mechanisms

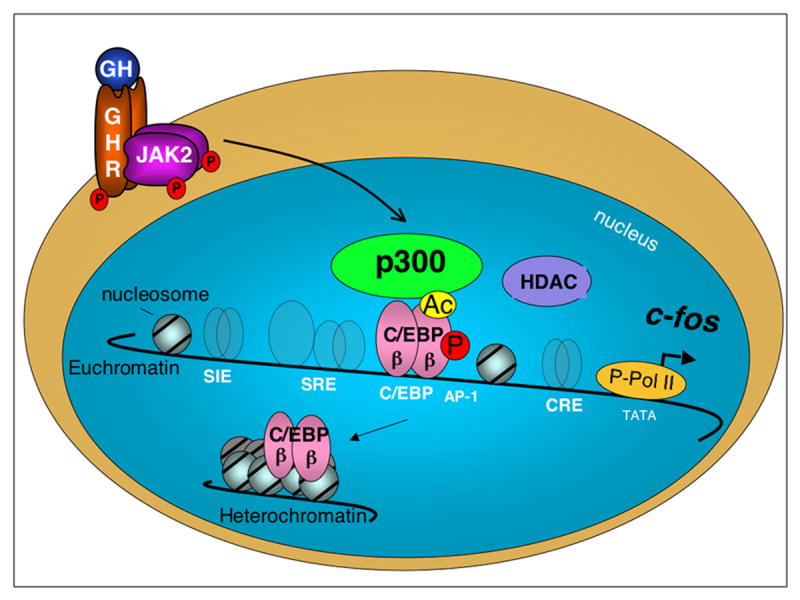

GH regulates transcription by multiple mechanisms involving a variety of post-translational modifications of transcription factors, dynamic assembly of nucleoprotein complexes and re-localization of transcription regulatory proteins in target cells. These mechanisms apply not only to Stat-dependent effects of GH, but are also involved in the similarly complex C/EBPβ-dependent transcription of GH-stimulated target genes. The following model is suggested for C/EBPβ-mediated transcription of GH regulated genes (Fig. 4): In responsive cells treated with GH, C/EBPβ undergoes a rapid transient phosphorylation and a delayed dephosphorylation (57, 58); these events appear to be coupled sequentially to the rapid, transient activation and delayed cessation of c-fos expression, respectively. Acetylation of C/EBPβ in its transcriptional activation domain appears to serve an activating role in GH-stimulated transcription; these and other post-translational modifications of C/EBPβ can potentially be coordinated for c-fos transcription in response to GH. Among these events, GH rapidly and transiently induces the occupancy of C/EBPβ and the coactivator p300, and possibly other nuclear proteins such as HDACs, as part of a complex or complexes of proteins on GH-responsive promoters that mediate activation of transcription. GH-induced modifications in the nuclear proteins participating in transcription complexes, as well as their re-localization in the cell, are likely to serve as coordinating mechanisms for integrating GH signals to regulate transcription. Similar integration involving other nuclear proteins including Stats appears to be a feature of regulation by GH of other genes. Each component of the diverse mechanisms for GH-regulated transcription reveals additional targets for potential therapeutic interventions in conditions such as impaired growth, catabolic states and insulin resistance.

Figure 4. GH regulates transcription of c-fos by multiple mechanisms.

The schematic illustrates regulation of transcription of c-fos by GH in a target cell. Interaction of GH with its receptor (GHR) and activation of JAK2 initiates multiple signaling pathways (not shown, see (16)) that regulate transcription factors on the c-fos promoter. The GH-responsive sequences on the c-fos promoter are indicated, and the associated transcription factors are represented in the background. Regulation of the critical transcription factor C/EBPβ by GH illustrates the importance of post-translational modifications: Phosphorylation (P) of C/EBPβ modulates c-fos promoter activation by GH. C/EBPβ is also acetylated (Ac) by p300, which also contributes to activation of c-fos by GH. GH also rapidly induces the formation of a nucleoprotein complex containing both C/EBPβ and p300, leading to co-activation which determines a baseline for GH-stimulated c-fos expression. MAPK-dependent phosphorylated C/EBPβ occupies the c-fos promoter in response to GH. These events coincide with increased occupancy of phosphorylated RNA polymerase II (P-Pol II) on c-fos and increased c-fos mRNA expression. HDACs can also participate in complexes that regulate c-fos expression. GH can also induce the rapid subnuclear re-localization of C/EBPβ to heterochromatin. These diverse GH-induced events involving C/EBPβ are coordinated to induce c-fos expression in response to GH.

Acknowledgments

These studies were supported by NIH grant DK46072 and NSF Grant 00-80193 to J. Schwartz, by NIH grant 5P60 DK20572 to R. Kwok, NIH grant DK061656 to J Iñiguez-Lluhí. This work used multiple core facilities of the Michigan Diabetes Research and Training Center funded by NIH (5P60DK20572). T. Cesena was supported by an individual NIH predoctoral fellowship (DK074377), a predoctoral traineeship from the Center for Organogenesis (NIH T32-HD07505), the Training Program in Cellular and Molecular Biology (T32 GM07315) and by an NSF/Rackham Merit Fellowship from the University of Michigan. G. Piwien-Pilipuk was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Center for Organogenesis (NIH T32-HD07505), and by CONICET grant PIP-6167 and ANPCyT grant PICT2004-26495.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Houssay BA, Biasotti A. Hypophysectomie et diabete pancreatique chez le crapaud. C R Soc Biol (Paris) 1930;104:407–412. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith RWJ, Gaebler OH, Long CNH. The Hypophyseal Growth Hormone, Nature and Actions. McGraw-Hill; NY: 1955. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaplan SL. Hormonal regulation of growth and metabolic effects of growth hormone. In: Kostyo JL, editor. Hormonal Control of Growth. American Physiological Soc.; NY: 1999. pp. 129–143. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Isaksson OG, Lindahl A, Nilsson A, Isgaard J. Mechanism of the stimulatory effect of growth hormone on longitudinal bone growth. Endocr Rev. 1987;8:426–438. doi: 10.1210/edrv-8-4-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daughaday WH, Rotwein P. Insulin-like growth factors I and II. Peptide, messenger ribonucleic acid and gene structures, serum, and tissue concentrations. Endocr Rev. 1989;10:68–91. doi: 10.1210/edrv-10-1-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green H. A dual effector theory of growth hormone action. Differentiation. 1985;29:195–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1985.tb00316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenfeld RG, Hwa V. Toward a molecular basis for idiopathic short stature. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:1066–1067. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davidson MB. Effect of growth hormone on carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. Endocr Rev. 1987;8:115–131. doi: 10.1210/edrv-8-2-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fryburg DA, Barrett EJ. The regulation of amino acid and protein metabolism by growth hormone. In: Kostyo JL, editor. Hormonal Control of Growth. American Physiological Soc; NY: 1999. pp. 515–536. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drange MR, Melmed S. Molecular pathogenesis of acromegaly. Pituitary. 1999;2:43–50. doi: 10.1023/a:1009917920589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rizza RA, Mandarino JL, Gerich JE. Effects of growth hormone on isulin action in man: Mechanisms of insulin resistance, impaired suppression of glucose production, and impaired stimulation of glucose utilization. Diabetes. 1982;31:663–669. doi: 10.2337/diab.31.8.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smit LS, Meyer DJ, Argetsinger LS, Schwartz J, Carter-Su C. Molecular events in growth hormone-receptor interaction and signaling. In: Kostyo JL, editor. Handbook of Physiology. Oxford University Press; New York: 1999. pp. 445–480. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herrington J, Carter-Su C. Signaling pathways activated by the growth hormone receptor. Trends Endo Metab. 2001;12:252–257. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(01)00423-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Argetsinger LS, Campbell GS, Yang X, Wittuhn BA, Silvennoinen O, Ihle JN, Carter-Su C. Identification of JAK2 as a growth hormone receptor-associated tyrosine kinase. Cell. 1993;74:237–244. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90415-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herrington J, Smit LS, Schwartz J, Carter-Su C. The role of STAT proteins in growth hormone signaling. Oncogene. 2000;19:2585–2597. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piwien-Pilipuk G, Huo JS, Schwartz J. Growth hormone signal transduction. J Pediat Endo Metab. 2002;15:771–786. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2002.15.6.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paukku K, Silvennoinen O. STATs as critical mediators of signal transduction and transcription: lessons learned from STAT5. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2004;15:435–455. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Udy GB, Towers RP, Snell RG, Wilkins RJ, Park SH, Ram PA, Waxman DJ, Davey HW. Requirement of STAT5b for sexual dimorphism of body growth rates and liver gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:7239–7244. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fang P, Kofoed EM, Little BM, Wang X, Ross RJ, Frank SJ, Hwa V, Rosenfeld RG. A mutant signal transducer and activator of transcription 5b, associated with growth hormone insensitivity and insulin-like growth factor-I deficiency, cannot function as a signal transducer or transcription factor. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:1526–1534. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woelfle J, Rotwein P. In vivo regulation of growth hormone-stimulated gene transcription by STAT5b. Am J Physiol - Endo Metab. 2004;286:E393–E401. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00389.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woelfle J, Chia DJ, Rotwein P. Mechanisms of growth hormone (GH) action. Identification of conserved Stat5 binding sites that mediate GH-induced insulin-like growth factor-I gene activation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:51261–51266. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309486200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woelfle J, Billiard J, Rotwein P. Acute control of insulin-like growth factor-I gene transcription by growth hormone through Stat5b. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:22696–22702. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301362200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benbassat C, Shoba LNN, Newman M, Adamo ML, Frank SJ, Lowe WL., Jr Growth hormone-mediated regulation of insulin-like growth factor I promoter activity in C6 glioma cells. Endocrinology. 1999;140:3073–3081. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.7.6762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frost RA, Nystrom GJ, Lang CH. Regulation of IGF-I mRNA and signal transducers and activators of transcription-3 and -5 (Stat-3 and -5) by GH in C2C12 myoblasts. Endocrinology. 2002;143:492–503. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.2.8641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davey HW, Xie T, McLachlan MJ, Wilkins RJ, Waxman DJ, Grattan DR. STAT5b is required for GH-induced liver IGF-I gene expression. Endocrinology. 2001;142:3836–3841. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.9.8400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bergad PL, Schwarzenberg SJ, Humbert JT, Morrison M, Amarasinghe S, Towle HC, Berry SA. Inhibition of growth hormone action in models of inflammation. Am J Physiol - Cell Physiol. 2000;279:C1906–C1917. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.6.C1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Le Cam A, Pantescu V, Paquereau L, Legraverend C, Fauconnier G, Asins G. cis-acting elements controlling transcription from rat serine protease inhibitor 2.1 gene promoter. Characterization of two growth hormone response sites and a dominant purine-rich element. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:21532–21539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bergad PL, Shih HM, Towle HC, Schwarzenberg SJ, Berry SA. Growth hormone induction of hepatic serine protease inhibitor 2.1 transcription is mediated by a Stat5-related factor binding synergistically to two gamma-activated sites. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:24903–24910. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.42.24903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sliva D, Wood TJJ, Schindler C, Lobie PE, Norstedt G. Growth hormone specifically regulates serine protease inhibitor gene transcription via gamma-activated sequence-like DNA elements. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:26208–26214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sundseth SS, Alberta JA, Waxman DJ. Sex-specific, growth hormone-regulated transcription of the cytochrome P450 2C11 and 2C12 genes. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:3907–3914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Waxman DJ, Ram PA, Park SH, Choi HK. Intermittent plasma growth hormone triggers tyrosine phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of a liver-expressed, Stat 5-related DNA binding protein. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:13262–13270. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.13262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holloway MG, Laz EV, Waxman DJ. Codependence of growth hormone-responsive, sexually dimorphic hepatic gene expression on signal transducer and activator of transcription 5b and hepatic nuclear factor 4α. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:647–660. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gurland G, Ashcom G, Cochran BH, Schwartz J. Rapid events in growth hormone action. Induction of c-fos and c-jun transcription in 3T3-F442A preadipocytes. Endocrinology. 1990;127:3187–3195. doi: 10.1210/endo-127-6-3187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Doglio A, Dani C, Grimaldi P, Ailhaud G. Growth hormone stimulates c-fos gene expression by means of protein kinase C without increasing inositol lipid turnover. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:1148–1152. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.4.1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meyer DJ, Campbell GS, Cochran BH, Argetsinger LS, Larner AC, Finbloom DS, Carter-Su C, Schwartz J. Growth hormone induces a DNA binding factor related to the interferon-stimulated 91-kDa transcription factor. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:4701–4704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campbell GS, Meyer DJ, Raz R, Levy DE, Schwartz J, Carter-Su C. Activation of acute phase response factor (APRF)/Stat3 transcription factor by growth hormone. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:3974–3979. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.8.3974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gronowski AM, Rotwein P. Rapid changes in gene expression after in vivo growth hormone treatment. Endocrinology. 1995;136:4741–4748. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.11.7588201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gronowski AM, Rotwein P. Rapid changes in nuclear protein tyrosine phosphorylation after growth hormone treatment in vivo. Identification of phosphorylated mitogen-activated protein kinase and stat91. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:7874–7878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liao J, Hodge CL, Meyer DJ, Ho PS, Rosenspire KC, Schwartz J. Growth hormone regulates Ternary Complex Factors and Serum Response Factor associated with the c-fos Serum Response Element. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:25951–25958. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meyer DJ, Stephenson EW, Johnson L, Cochran BH, Schwartz J. The serum response element can mediate induction of c-fos by growth hormone. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6721–6725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gronowski AM, Stunff CL, Rotwein P. Acute nuclear actions of growth hormone (GH): Cycloheximide inhibits inducible activator protein-1 activity, but does not block GH-regulated signal transducer and activator of transcription activation or gene expression. Endocrinology. 1996;137:55–64. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.1.8536642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Slootweg MC, deGroot R, Hermann EM, Koornneef I, Kruijer W, Kramer YM. Growth hormone induces expression of c-jun and junB oncogenes and employs a protein kinase C signal transduction pathway for the induction of c-fos gene expression. J Mol Endocrinol. 1991;6:179–188. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0060179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clarkson RWE, Chen CM, Harrison S, Wells C, Muscat GEO, Waters MJ. Early responses of trans-activating factors to growth hormone in preadipocytes: differential regulation of CCAAT Enhancer-Binding Protein-β (C/EBPβ) and C/EBPδ. Molec Endocrinol. 1995;9:108–120. doi: 10.1210/mend.9.1.7760844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen CM, Clarkson RW, Xie Y, Hume DA, Waters MJ. Growth hormone and colony-stimulating factor 1 share multiple response elements in the c-fos promoter. Endocrinology. 1995;136:4505–4516. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.10.7664671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yarwood SJ, Kilgour E, Anderson NG. Cyclic AMP potentiates growth hormone-dependent differentiation of 3T3-F442A preadipocytes: possible involvement of the transcription factor CREB. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1998;138:41–50. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(98)00049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sassone-Corsi P, Visvader J, Ferland L, Mellon PL, Verma IM. Induction of proto-oncogene fos transcription through the adenylate cyclase pathway: characterization of a cAMP-responsive element. Genes Dev. 1988;2:1529–1538. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.12a.1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boutillier AL, Barthel F, Roberts JL, Loeffler JP. B-adrenergic stimulation of cFOS via protein kinase A is mediated by cAMP regulatory element binding protein (CREB)-dependent and tissue-specific CREB-independent mechanisms in corticotrope cells. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:23520–23526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cui TX, Piwien-Pilipuk G, Huo JS, Kaplani J, Kwok R, Schwartz J. Endogenous CCAAT/enhancer binding protein β and p300 are both regulated by growth hormone to mediate transcriptional activation. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:2175–2186. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Croniger C, Trus M, Lysek-Stupp K, Cohen H, Liu Y, Darlington GJ, Poli V, Hanson RW, Reshef L. Role of the isoforms of CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein in the initiation of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (GTP) gene transcription at birth. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:26306–26312. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.42.26306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen X, Liu W, Ambrosino C, Ruocco MR, Poli V, Romani L, Quinto I, Barbieri S, Holmes KL, Venuta S, Scala G. Impaired generation of bone marrow B lymphocytes in mice deficient in C/EBPβ. Blood. 1997;90:156–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sieh A, Li PS, Schwartz J. Growth hormone-regulated gene transcription in the absence of C/EBP beta. Prog 85th Mtg Endocrine Soc. 2003:380. (abs) [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nerlov C, Ziff EB. CCAAT/enhancer binding protein-alpha amino acid motifs with dual TBP and TFIIB binding ability co-operate to activate transcription in both yeast and mammalian cells. EMBO J. 1995;14:4318–4328. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00106.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stein B, Cogswell PC, Baldwin AS., Jr Functional and physical associations between NF-κ B and C/EBP family members: a Rel domain-bZIP interaction. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:3964–3974. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.7.3964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mink S, Haenig B, Klempnauer KH. Interaction and functional collaboration of p300 and C/EBPβ. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6609–6617. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.11.6609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kowenz-Leutz E, Leutz A. A C/EBPβ isoform recruits the SWI/SNF complex to activate myeloid genes. Mol Cell. 1999;4:735–743. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80384-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Darlington GJ, Ross SE, MacDougald OA. The role of C/EBP genes in adipocyte differentiation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:30057–30060. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Piwien-Pilipuk G, MacDougald OA, Schwartz J. Dual regulation of phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of C/EBPβ modulate its transcriptional activation and DNA binding in response to growth hormone. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:44557–44565. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206886200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Piwien-Pilipuk G, Van Mater D, Ross SE, MacDougald OA, Schwartz J. Growth hormone regulates phosphorylation and function of C/EBP beta by modulating Akt and glycogen synthase kinase-3. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:19664–19671. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010193200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Berger SL. Histone modifications in transcriptional regulation. Curr Op Gen Dev. 2002;12:142–148. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(02)00279-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jenuwein T, Allis CD. Translating the histone code. Science. 2001;293:1074–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1063127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kovacs KA, Steinmann M, Magistretti PJ, Halfon O, Cardinaux JR. CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein family members recruit the coactivator CREB-binding protein and trigger its phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:36959–36965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303147200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kwok RP, Lundblad JR, Chrivia JC, Richards JP, Bachinger HP, Brennan RG, Roberts SG, Green MR, Goodman RH. Nuclear protein CBP is a coactivator for the transcription factor CREB. Nature. 1994;370:223–226. doi: 10.1038/370223a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arany Z, Sellers WR, Livingston DM, Eckner R. E1A-associated p300 and CREB-associated CBP belong to a cnserved family of coactivators. Cell. 1994;77:799–800. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90127-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shikama N, Lyon J, La Thangue NB. The p300/CBP family: integrating signals with transcription factors and chromatin. Trends in Cell Biol. 1997;7:230–236. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(97)01048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fass DM, Butler JE, Goodman RH. Deacetylase activity is required for cAMP activation of a subset of CREB target genes. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:43014–43019. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305905200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Holmstrom S, Van Antwerp ME, Iniguez-Lluhi JA. Direct and distinguishable inhibitory roles for SUMO isoforms in the control of transcriptional synergy. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:15758–15763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2136933100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Subramanian L, Benson MD, Iniguez-Lluhi JA. A synergy control motif within the attenuator domain of CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha inhibits transcriptional synergy through its PIASy-enhanced modification by SUMO-1 or SUMO-3. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:9134–9141. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210440200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Johnson ES. Protein modification by SUMO. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:355–382. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.074118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kim J, Cantwell CA, Johnson PF, Pfarr CM, Williams SC. Transcriptional activity of CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins is controlled by a conserved inhibitory domain that is a target for sumoylation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:38037–38044. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207235200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Eaton EM, Sealy L. Modification of CCAAT/Enhancer-binding Protein-beta by the Small Ubiquitin-like Modifier (SUMO) family members, SUMO-2 and SUMO-3. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:33416–33421. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305680200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Piwien-Pilipuk G, Thompson BA, Mazurkiewicz-Munoz AM, Subramanian L, Iniguez-Lluhi JA, Schwartz J. Sumoylation of C/EBPβ modulates GH-stimuulated gene transcription. The 86th Annual Meeting of the Endocrine Society. 2004:498. [Google Scholar]

- 72.McKenna NJ, O'Malley BW. Combinatorial control of gene expression by nuclear receptors and coregulators. Cell. 2002;108:465–474. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00641-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Freedman LP. Increasing the complexity of coactivation in nuclear receptor signaling. Cell. 1999;97:5–8. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80708-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Roeder RG. The role of general initiation factors in transcription by RNA polymerase II. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:327–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Xu L, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG. Coactivator and corepressor complexes in nuclear receptor function. Curr Opinion Genet Devel. 1999;9:140–147. doi: 10.1016/S0959-437X(99)80021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Smith JL, Collins I, Chandramouli GV, Butscher WG, Zaitseva E, Freebern WJ, Haggerty CM, Doseeva V, Gardner K. Targeting combinatorial transcriptional complex assembly at specific modules within the interleukin-2 promoter by the immunosuppressant SB203580. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:41034–41046. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305615200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lonard DM, O'Malley BW. Expanding functional diversity of the coactivators. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30:126–132. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bouras T, Fu M, Sauve AA, Wang F, Quong AA, Perkins ND, Hay RT, Gu W, Pestell RG. SIRT1 deacetylation and repression of p300 involves lysine residues 1020/1024 within the cell cycle regulatory domain 1. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:10264–10276. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408748200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pfitzner E, Jahne R, Wissler M, Stoecklin E, Groner B. p300/CREB-binding protein enhances the prolactin-mediated transcriptional induction through direct interaction with the transactivation domain of Stat5, but does not participate in the Stat5-mediated suppression of the glucocorticoid response. Mol Endocrinol. 1998;12:1582–1593. doi: 10.1210/mend.12.10.0180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ling L, Lobie PE. RhoA/ROCK activation by growth hormone abrogates p300/histone deacetylase 6 repression of Stat5-mediated transcription. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:32737–32750. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400601200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Brivanlou AH, Darnell JEJ. Signal transduction and the control of gene expression. Science. 2002;295:813–818. doi: 10.1126/science.1066355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Piwien-Pilipuk G, Galigniana MD, Schwartz J. Subnuclear localization of C/EBPβ is regulated by growth hormone and dependent on MAPK. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:35668–35677. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305182200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]