Abstract

Virtually all behavioral and neurophysiological studies have shown that sustained (endogenous, conceptually driven) attention enhances perception. But can this enhancement be held indefinitely? We assessed the time course of attention’s effects on contrast sensitivity, reasoning that if attention does indeed boost stimulus strength, the strengthened representation could result in stronger adaptation over time. We found that attention initially enhances contrast sensitivity, but that over time sustained attention can actually impair sensitivity to an attended stimulus.

Our ability to process information is severely restricted by the bio-energetic cost of cortical computation—a constraint at odds with the seemingly limitless amount of information in our environment. Given that our visual system can only process a small fraction of this information simultaneously, visual attention plays a crucial role by selecting information for prioritized processing. Covert attention (attending to a given location in the absence of eye movements) operates by strengthening the representation of relevant stimuli1–7. This modulation occurs for basic dimensions of visual processing, such as contrast sensitivity1–7. Neurophysiological studies have shown that sustained attention amplifies the contrast gain of neural responses in early visual cortex, supporting the notion that attention enhances the representation of a stimulus in a manner akin to boosting its physical contrast3,4,6,7.

Are the facilitatory effects of sustained attention stable over time? Attention aside, it is established that contrast sensitivity decreases as a function of presentation time, owing to contrast adaptation. Selective adaptation is the decreased sensitivity following prolonged exposure to a stimulus. Neurophysiologically, this reduced sensitivity has been attributed to a contrast gain control mechanism, whereby adaptation decreases the gain of detectors tuned to the adapter stimulus8. It is known that the magnitude of adaptation increases with the intensity of the adapter stimulus. For instance, adapting to higher contrast gratings results in greater threshold elevation9 and longer recovery time10. If sustained attention actually amplifies the contrast signal of a stimulus3,6,7, one might expect that, because the observer would now be adapting to an attention-amplified, ‘higher contrast’ stimulus, this could result in stronger, longer-lasting adaptation effects—thereby impairing sensitivity more than in the unattended, neutral case.

Can attention to a stimulus therefore actually impair contrast sensitivity? In the present study, we characterized the time course of attention and its effects on contrast sensitivity. We hypothesized that attention first enhances contrast sensitivity (consistent with previous studies3–5), and over time—due to prolonged adaptation to an attention-amplified stimulus—diminishes sensitivity more than when attention is absent.

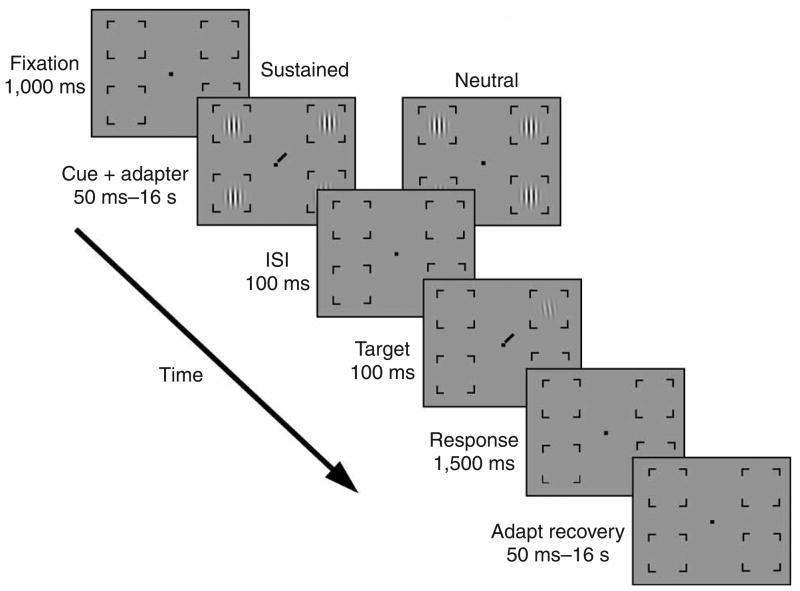

Four observers (three naïve) participated in the study. In each trial of experiment 1, three observers maintained fixation for varying durations, while they were shown four vertical adapter grating stimuli in the periphery (Fig. 1). While they adapted to these gratings, they were also required to attend to one of the four 70% contrast adapter gratings (sustained condition) or to view all four stimuli (neutral condition). The adapter gratings were followed by a slightly tilted test grating, at one of the four locations. Observers reported whether the test grating was tilted to the right or to the left. We obtained contrast thresholds at 75% accuracy using a staircase procedure. Performance on this orientation discrimination task depends on contrast sensitivity1–5.

Figure 1.

The trial sequence. In each trial, observers viewed a fixation point, followed by four vertically oriented adapter Gabor gratings (2° × 2°; 4 cycles per deg; 70% contrast) positioned at the four possible target locations (7° eccentricity). To minimize luminance adaptation and maximize contrast adaptation, flickering gratings were used (counterphase modulated at 8 Hz). Simultaneous with the adapter gratings, one of two types of cues appeared: a sustained attentional cue or a neutral cue, which served as a baseline. The sustained attentional cue was a line at fixation, directing observers to attend to the location of the upcoming target. The neutral cue was a dot at the center of the screen, which gave no information about the upcoming target location. The display duration of the cue + adapter varied from 50 ms to 16s. After a brief blank interval (interstimulus interval, ISI), the target stimulus appeared—a grating similar to the adapter, tilted ±3° from the vertical. Observers performed a two-alternative forced-choice orientation discrimination task. To equate location uncertainty between the precued and neutral conditions, we presented a cue at the center of the screen in both conditions; this indicated the target location and appeared simultaneously with the target. Contrast thresholds for the target stimulus were obtained at 75% accuracy using a staircase procedure. Nine thresholds were obtained per condition. To ensure observers’ uninterrupted fixation, eye movements were monitored by infrared camera. We discarded those (rare) trials in which breaks from fixation were detected (< 1%).

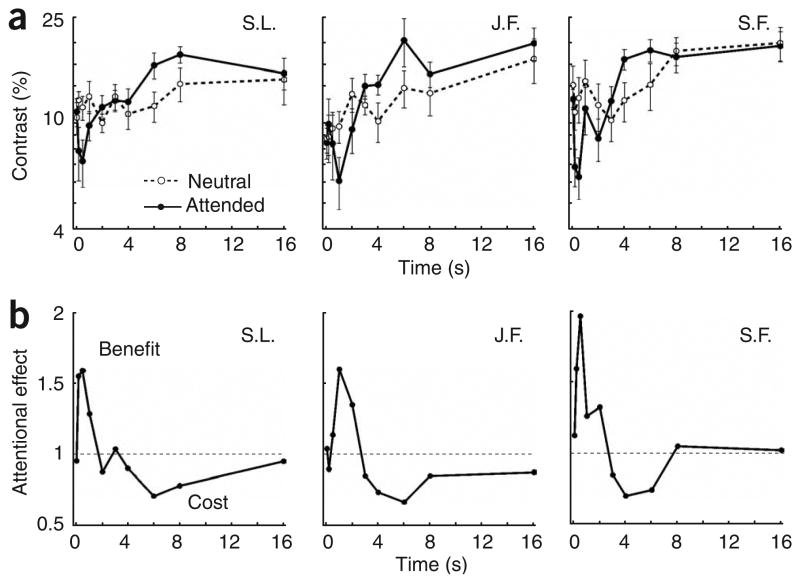

For all three observers in the neutral condition (Fig. 2a), contrast thresholds increased over time, as would be expected given contrast adaptation8. In the sustained attention condition, there was an initial benefit: thresholds were lowered in the attended condition. This attentional enhancement of contrast sensitivity (1/threshold) is consistent with previous findings3,4. It is possible that the initial benefit was due to reduced forward masking by attention. At short durations, there is little difference between the effects of forward masking and adaptation on threshold elevation11. Moreover, we found that over time, the attentional benefit disappeared, and sustained attention eventually led to impaired contrast sensitivity relative to that in the neutral condition. Note that an uncertainty reduction explanation of attention3–5 cannot account for an attentional impairment. The attentional ratio (contrast thresholds for neutral/sustained, Fig. 2b) demonstrated the initial benefit of attention (ratio > 1) and the subsequent cost (ratio < 1). For all three observers, the difference between attended and neutral conditions diminished by 16 s. Sustaining attention at a location for such long durations is taxing, and we suspect that the reduction in impairment with attention at long durations could be due to a weakening of the ability to sustain attention.

Figure 2.

The effect of sustained attention over time. (a) Contrast thresholds as a function of time. In the neutral condition (dashed line), thresholds increased with time due to contrast adaptation. However, with sustained attention (solid line), thresholds first decreased and then increased. A within-subjects two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) on the log-transformed thresholds revealed a main effect of duration (F1,517 = 10.62, P < 0.0001) and an attention × duration interaction (F1,517 = 4.01, P < 0.0001). Error bars correspond to s.e.m. (b) Attentional cost/benefit ratios (neutral/attended) as a function of time. Points falling on the line y = 1 indicate no effect, points above this line indicate a benefit, and points below it indicate a cost. For all three observers, there was an initial attentional benefit and a subsequent cost over time.

To quantify how much the adapter contrast was boosted by attention, we assessed how much higher the contrast of the adapting grating needed to be so as to match the effect of attention. By varying the adapter contrast in the neutral condition under a fixed adaptation duration (6 s), we found that observers needed 11–14% higher adapter contrast in order for their threshold elevation to match that found with a 70% contrast adapter in the attended condition (P < 0.05; adapter contrasts: J.F. = 81%, S.L. = 83%, S.F. = 84%). These results demonstrated that attention amplified the strength of a 70% contrast adapter as if its physical contrast were 81–84%.

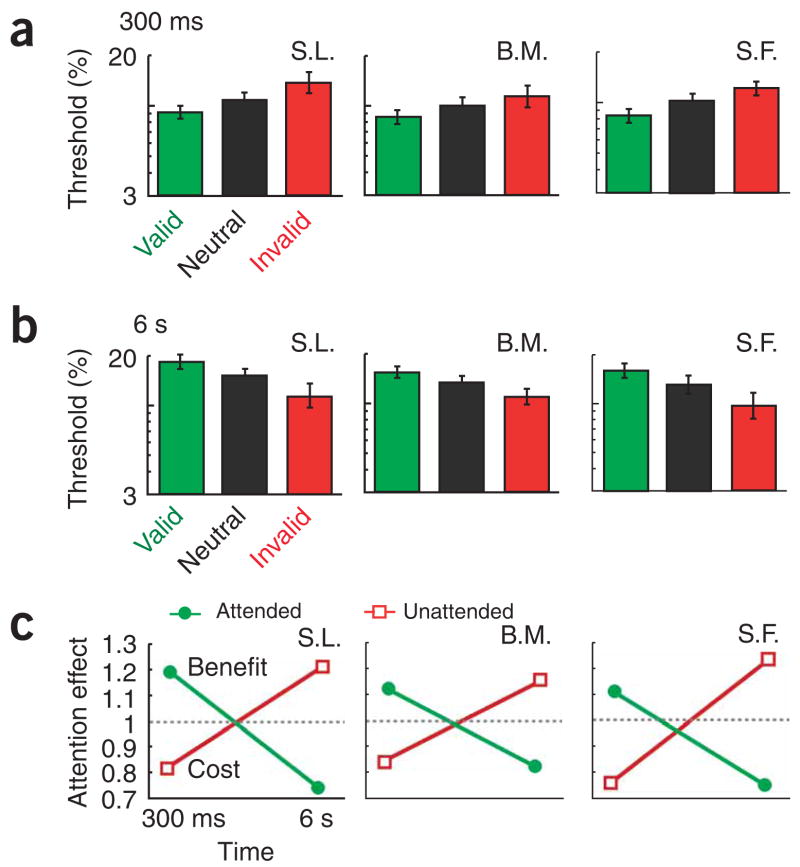

How are unattended locations affected? In a second experiment, we incorporated an invalid cue condition to investigate how contrast adaptation is affected at unattended locations (details in Supplementary Methods online). We predicted that under long adaptation durations, if the strength of unattended signals is suppressed, unattended locations would result in weaker contrast adaptation compared to that in a neutral condition. For all three observers, short adaptation duration (300 ms) thresholds were lowest for the valid (attended) condition and highest for the invalid (unattended) condition (Fig. 3a). This effect is consistent with previous studies1,4,5. Notably, with the 6 s adaptation duration, the effect was reversed (Fig. 3b): thresholds were highest for the valid, attentional condition and lowest for the invalid, unattended condition. The attentional effect ratios (Fig. 3c) demonstrated that at 300 ms, the valid cue yielded a benefit, whereas the invalid cue yielded a cost. However, at 6 s, the attended condition led to a cost in contrast sensitivity whereas the unattended one led to a benefit. These results indicate that attention increases the signal strength of the attended adapter and suppresses the signal strength of unattended adapters.

Figure 3.

How unattended adapters are affected over time. (a) Contrast thresholds at the 300-ms adaptation duration for the valid, neutral and invalid cue conditions. For all observers, thresholds were lowest with the valid cue (attended) and highest with the invalid cue (unattended). (b) At 6 s, the pattern was reversed: thresholds were highest with the valid cue (attended) and lowest with the invalid cue (unattended). (c) Attentional cost/benefit ratios (neutral/cued) as a function of time. Points falling on the line y = 1 indicate no effect of attention, points above this line indicate a benefit, and those below it indicate a cost. For all three observers, at 300 ms the valid cue (attended) yielded a benefit (ratio > 1) and the invalid cue (unattended) yielded a cost (ratio < 1). At 6 s, the pattern was reversed: the valid cue led to a cost in contrast sensitivity (ratio < 1) and the invalid cue led to a benefit (ratio > 1).

These results are consistent with single-unit studies reporting that sustained attention to a stimulus amplifies the contrast gain of neurons in areas of visual cortex such as V4 and MT6,7—almost as if the physical contrast amplitude of the stimulus were ‘turned up’ by attention. Here, we show that attention does indeed boost contrast sensitivity, but prolonged exposure to this higher contrast stimulus results in greater contrast adaptation, and contrast sensitivity to a subsequent, similar test stimulus is impaired by attention. Contrast adaptation occurs at a number of levels in visual cortex, starting as early as VI8,12. By demonstrating attentional modulation of adaptation, the present study shows that the effect of attention on perception occurs early in the visual stream, which is consistent with results from single-unit6,7 and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies2,13.

Psychophysical and neuroimaging studies have shown that attention can modulate adaptation, as has been observed with motion aftereffects14. Indeed, it has been proposed that attention can diminish the representation of a stimulus. The finding that Troxler fading seems to be modulated by attention has been interpreted as a result of a directly inhibitory effect of attention on sensory processing15. We propose that this fading can be explained within the framework of attentional enhancement, as follows: because attention boosts the strength of a signal, adaptation increases over time, thus impairing contrast sensitivity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank T. Liu and all the members of the Carrasco lab for helpful discussions. This work was funded by the US National Institutes of Health (S.L.).

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Both authors contributed equally to this project.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Carrasco M, Ling S, Read S. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:308–313. doi: 10.1038/nn1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu T, Pestilli F, Carrasco M. Neuron. 2005;45:469–477. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ling S, Carrasco M. Vision Res. 2006;46:1210–1220. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dosher BA, Lu ZL. Vision Res. 2000;40:1269–1292. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(00)00019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pestilli F, Carrasco M. Vision Res. 2005;45:1867–1875. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2005.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reynolds JH, Pasternak T, Desimone R. Neuron. 2000;26:703–714. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81206-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martinez-Trujillo J, Treue S. Neuron. 2002;35:365–370. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00778-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohzawa I, Sclar G, Freeman RD. Nature. 1982;298:266–268. doi: 10.1038/298266a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langley K. Spat Vis. 2002;16:77–93. doi: 10.1163/15685680260433922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenlee MW, Georgeson MA, Magnussen S, Harris JP. Vision Res. 1991;31:223–236. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(91)90113-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foley JM, Boynton GM. Vision Res. 1993;33:959–980. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(93)90079-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Movshon JA, Lennie P. Nature. 1979;278:850–852. doi: 10.1038/278850a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brefczynski JA, DeYoe EA. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:370–374. doi: 10.1038/7280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alais D, Blake R. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:1015–1018. doi: 10.1038/14814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lou L. Perception. 1999;28:519–526. doi: 10.1068/p2816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.