Abstract

Somatosensory and auditory feedback mechanisms are dynamic components of the vocal motor pattern generator in mammals. This review explores how sensory cues arising from central auditory and somatosensory pathways actively guide the production of both simple sounds and complex phrases in mammals. While human speech is a uniquely sophisticated example of mammalian vocal behavior, other mammals can serve as examples of how sensory feedback guides complex vocal patterns. Echolocating bats in particular are unique in their absolute dependence on voice control for survival: these animals must constantly adjust the acoustic and temporal patterns of their orientation sounds to efficiently navigate and forage for insects at high speeds under the cover of darkness. Many species of bats also utter a broad repertoire of communication sounds. The functional neuroanatomy of the bat vocal motor pathway is basically identical to other mammals, but the acute significance of sensory feedback in echolocation has made this a profitable model system for studying general principles of sensorimotor integration with regard to vocalizing. Bats and humans are similar in that they both maintain precise control of many different voice parameters, both exhibit a similar suite of responses to altered auditory feedback, and for both the efficacy of sensory feedback depends upon behavioral context. By comparing similarities and differences in the ways sensory feedback influences voice in humans and bats, we may shed light on the basic architecture of the mammalian vocal motor system and perhaps be able to better distinguish those features of human vocal control that evolved uniquely in support of speech and language.

Keywords: vocalization, speech, midbrain, sensorimotor integration, echolocation

Introduction

A central question in neuroscience is how complex motor patterns are coordinated in the mammalian brain. Vocal motor patterns, especially in humans, are complex examples of how the brain incorporates sensory feedback from a diverse array of auditory, tactile and proprioceptive sources as it coordinates activity in multiple major muscle groups. Yet vocal communication is of singular importance in human affairs, and speech and language are widely regarded as one of the defining characteristics of being human. Thus, investigations into how the human brain generates speech are driven not just by questions of mechanisms, but also by a desire to know what distinguishing features of our brains make us human.

All terrestrial mammals vocalize using the same basic sets of respiratory and laryngeal muscles [60]. Mammalian vocalizations typically include coordinated movements of the jaw, lips, or tongue for the purpose of shaping the acoustic properties of the voice, and the integration of proprioceptive and tactile feedback from the mouth and nasal cavity is essential for guiding these complex interactions [39, 41]. Somatosensory feedback arising from the larynx is essential for the normal control of both pitch and timing of vocalizations, and somatosensory feedback from the lungs is essential for the efficient coordination of vocalizing with breathing. Auditory feedback is essential both for vocal learning during critical phases of development and for the ongoing maintenance of normal sounding vocalizations [57]. Collectively, these sensory feedback pathways represent dynamic components of the vocal motor pattern generator in mammals. The relative significance of each individual feedback mechanism may vary among mammals depending upon the nature and sophistication of each species’ unique vocal repertoire, but a wealth of evidence supports the conclusion that all mammals, including humans, share a basically similar functional neuroanatomical organization of the vocal sensory-motor integration pathways [60]. To a large extent these similarities extend to other vertebrates, notably including songbirds [58], chorusing frogs [7], and even fish [35, 67]. Ultimately the neural substrate for human speech will perhaps be distinguished by its more elaborate and sophisticated cortical circuitry [88], but surprisingly, many of the normal ways in which human speech responds to sensory feedback, such as in the case of the Lombard effect [76] or the response to pitch-shifted feedback [9, 23], have been documented in a variety of other animals [54, 113, 116, 135]. This fact illustrates the value of exploring the comparative neurophysiology of vocal motor patterning. Yet despite the fact that many mammals vocalize, regrettably few exhibit the flexible repertoire, precise vocal control or stereotyped responsiveness that an experimentalist would like to have available to address issues that bear directly on the complexity of human speech.

In the study of how sensory feedback influences mammalian vocal motor pathways, humans have been used for a wide variety of psychoacoustic experiments often coupled with elegant in vivo neuroimaging techniques (PET, fMRI). Other mammals, in particular monkeys, cats and bats, have been widely used for more invasive electrophysiological and pharmacological studies of vocal control. A combination of methodological constraints and heuristic differences have led these two lines of research (humans versus “other”) down very different pathways, producing two largely independent sets of literature. In this review, I will attempt to bridge this gap by identifying behavioral similarities between humans and other mammals and discussing how those behaviors have been exploited neurophysiologically.

What vocal parameters are controlled by sensory feedback?

For comparative purposes it behooves us to focus on a few standardized acoustic parameters, namely the frequency, loudness and temporal patterns of vocalizations. The frequency, or pitch, of a vocalization can be a very complex and variable parameter, and correspondingly a variety of different specific measurements are sometimes necessary for characterizing the spectral characteristics of an animal’s voice. A sound’s fundamental frequency, its overall bandwidth, the number of harmonics present, the center frequency, and the relative loudness of different spectral components within a sound are just some of the more common measures of a sound’s spectral characteristics. Not all of these will be affected simultaneously or equally by the same sensory stimulus because they are in many circumstances controlled independently; for example, while a sound’s fundamental frequency is determined by muscle tension in the larynx, the bandwidth or number of harmonics present may be actively manipulated by changes in the shape of the oral and nasal cavities.

Loudness or intensity is a more straightforward parameter to measure, but also a highly flexible vocal parameter that all mammals appear able to regulate. Loudness control is mediated primarily via changes in subglottic pressure, which is manipulated through expiratory force and requires a delicate coordination between laryngeal and respiratory control systems. Because of a mechanical link between subglottic pressure and the control of voice pitch [53, 148], changes in loudness are often accompanied by or require compensatory changes in vocal pitch. Thus sensory feedback influences on loudness may often be coupled with changes in pitch, and vice versa.

Vocal timing can be strongly influenced by auditory feedback, but characterizing the “normal” temporal dynamics of vocal behavior in any mammal can be quite challenging. Humans can subjectively recognize when the temporal flow of their own or another’s speech is distorted or unnaturally sounding, as in the case of stuttering, dysarthria or apraxia of speech, yet there remains significant disagreements on how speech disorders like these are best quantified because there appears to be many different etiologies underlying different temporal patterns of stuttering and dysarthria [6, 16, 17, 150]. For example, stutterers may vary in the extent to which they exhibit within-word versus between-word disfluencies [15]. But while normal human speech is characterized by precisely stereotyped temporal sequences of sounds, most other mammals utter only single syllables or in rare cases short combinations of syllables. On a broad scale we might make the generalization that all mammalian vocalizations are similarly coordinated in time with regard to the respiratory cycle. The emission of single syllables can always be expressed in relationship to the phase of the respiratory cycle, and for most mammals this relationship appears quite stereotyped [145]; mammals typically initiate vocalizations nearer to the beginning rather than the end of expiration. Similarly, extended vocal sequences can be defined by the extent to which they create phase lags in the respiratory cycle; a single spoken phrase lasting slightly longer than a normal expiration may postpone the succeeding inspiration, thus creating the phase lag in the ensuing respiratory cycle. Ultimately however, continuous vocal sequences in any mammal must inevitably accommodate a return to rhythmic breathing. The respiratory cycle may therefore be viewed as an important internal clock that dictates the temporal patterns of all mammalian vocalizations, and as such may provide a common time frame for comparison of vocal temporal dynamics across species.

Somatosensory feedback influences on vocalizing

Supralaryngeal feedback contributions to human speech

Both normal and abnormal human speech patterns are strongly influenced by a variety of different somatosensory inputs. While the significance of auditory feedback for vocal learning is well established[2, 22, 56, 57, 70, 80], practically nothing is known of the roles other senses play as mammals learn to vocalize. Yet assuredly motor patterns as complex as human speech require significant proprioceptive and tactile feedback for coordinating the orofacial, laryngeal and respiratory components of speech, and these inputs cannot be any less important than auditory feedback for both the learning and maintenance of normal sounding vocalizations. These inputs are generally more difficult to manipulate experimentally, and correspondingly fewer studies have successfully broached this topic.

Conformational changes in the vocal tract leading to the production of different sounds are produced by the coordinated activity of multiple muscles and accompanying speech articulators, and several lines of research have improved our understanding of how the lips, jaw, tongue and larynx are coordinated in time during vocalizing. Mechanical perturbations of jaw and lip movements during the enunciation of vowels and consonants have revealed that automatic compensatory changes in both the scale and timing of articulatory movements are an essential aspect of normally sounding speech [28–30, 39, 41, 87]. For example, compensatory changes in upper and lower lip movements occur when jaw movement is retarded [28, 29], and alternately compensatory jaw and laryngeal movements occur in response to unexpected mechanical perturbations of the lower lip [30, 41, 87]. Such manipulations reveal the presence of extensive somatic sensory interactions between coordinated muscle groups and suggest that speech-related movements involve a considerable amount of reflexive sensorimotor interactions. However, related studies have also shown that there may be functional constraints on ways sensory feedback can influence articulatory movements: lip, jaw and laryngeal movements are highly constrained in their relative timings, and the extent to which sensory feedback can influence them depends on the identity of the sound being produced and on the phonetic context [40, 41]. Orofacial movements are also coordinated with breathing patterns both during and in the absence of speech, but of these, jaw movements appear most tightly coupled to respiratory drive [79]. The tongue is also centrally involved in the articulation of human speech, and provides both tactile and proprioceptive feedback during vocalizing [44]. Disrupting this feedback by anesthetizing the right side lingual nerve significantly altered speech production [5, 91], even including changes in the duration and frequency of vowels, which were otherwise hypothesized to be controlled exclusively by auditory feedback, since speakers do not “feel” vowels the same way they feel the mechanical interactions of their lips, tongue and teeth during the production of consonants [44]. Anesthetizing the trigeminal and glossopharyngeal nerves and branches of the vagus nerve also interrupt oral proprioceptive and tactile feedback pathways leading to distorted speech [48, 121, 149]. Somatosensory afferent projections arising from supralaryngeal structures have been traced into the brainstem where the most significant connections terminate in the principle and spinal trigeminal nuclei and the solitary tract nucleus [48, 60, 124, 149], but precisely where and how they direct vocal motor patterning is poorly understood.

Supralaryngeal feedback mechanisms in bat vocalizations

The coordination of supralaryngeal structures involved in vocalizing has been most extensively studied in humans. However, all mammalian vocalizations require some level of supralaryngeal control. For example jaw movements represent a fundamental component of vocal control, and the comparative study of how other mammals coordinate jaw movements during vocalizing offers significant potential benefits for understanding the functional nature of the mammalian vocal pattern generator. As an example, consider the difference between the vocal motor patterns of the horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus ferrumequinum) and the mustached bat (Pternotus parnellii). Horseshoe bats and mustached bats both emit structurally similar echolocation calls that are in each case uniquely distinguished by an unusually long, constant-frequency (CF) component bracketed at the beginning and ending by two short frequency modulated (FM) components. However while mustached bats emit their calls through their mouths, the horseshoe bats emit their calls through their nose. Horseshoe bats are unusual among mammals in that their jaw movements appear completely uncoupled from vocalizing, and indeed uncoupled even from breathing; in horseshoe bats the mouth isn’t used for vocalizing or breathing because of the tight mechanical coupling between the trachea and the nasal cavity [42]. A comparative analysis of the functional neuroanatomy underlying supralaryngeal feedback mechanisms in horseshoe bats and mustached bats might reveal important insights into the neural processes underlying jaw coordination during vocalizing.

Another example of precise supralaryngeal coordination in a non-human mammal comes in the way many echolocating bats regulate the bandwidth and harmonic structure of their echolocation calls. Modifying bandwidth is a common response to changing foraging conditions and greatly influences the temporal resolution and range discrimination capabilities of echolocating bats [42, 111, 131, 143]. These changes are often achieved through modifications of the vocal tract, including changes in the shape and dimensions of the tracheal, oral and nasal chambers which translate into substantial changes in acoustic transmittances [47, 146, 147]. Changes in echolocation call bandwidth are triggered by auditory cues and become incorporated into succeeding vocalizations within tens of millisecond, but precise control over the shape of the vocal tract depends upon constant guidance from supralaryngeal somatosensory feedback. Proprioceptive and tactile cues regarding the current shape of the vocal tract and positions of the tongue and lips are likely to act via reflexive brainstem pathways in a manner similar to the human response to lip and jaw perturbations.

Laryngeal and pulmonary sources of feedback

Coordination of laryngeal and respiratory activity is regulated by a basic network of interacting medullary and pontine feedback pathways that served such essential vertebrate behaviors as breathing, chewing, swallowing, drinking, vomiting, coughing and sneezing [107] long before terrestrial animals adapted this system for acoustic communication purposes. Laryngeal feedback generally serves two main processes during vocalizing, reflexive control of the laryngeal musculature and respiratory-laryngeal coordination. The types of sensory feedback arising from the larynx includes information regarding vibrations, tension across the vocal folds, subglottic pressure and airflow, and the relative positions of the laryngeal cartilages. This feedback arises from mechanosensors and free nerve endings located within the laryngeal muscosa and from within the laryngeal muscles and joints[1, 19] and is carried by the recurrent laryngeal nerve and the internal and external branches of the superior laryngeal nerve [11–13, 122, 123]. Stretch-receptors found in the intrinsic laryngeal muscles [92] are suspected of driving the recruitment of additional adductor and tensor muscle motoneurons in response to adductor stretching and vocal fold vibrations [123], thereby helping to regulate tension across the vocal membranes during vocalizing. Surprisingly, some evidence suggests that human speech is largely unimpaired by topical application of anesthesia to the laryngeal mucosa [38]. However more detailed studies in the cat have demonstrated that even the simplest vocal motor patterns are exquisitely sensitive to airflow and pressure-related proprioceptive feedback from the larynx [20]. Within the brainstem the ventrolateral portion of solitary tract nucleus (NST) seems to be the principle target of this feedback [61, 107], which in turn appears to send projections back onto the laryngeal motor neurons located in the nucleus ambiguus (NA), thereby creating a rapid laryngeal reflex.

However, laryngeal feedback is also centrally involved in respiratory control, and the NST is integrally involved in mediating respiratory reflexes [27, 105–107]. The NST integrates and relays proprioceptive information from the larynx to the parabrachial nucleus (PB) in the pons, which in turn projects back upon the medullary respiratory rhythm centers [10, 33, 85], as well as onto the laryngeal motor neurons of the NA and nucleus retroambiguus [60, 117]. Electrical stimulation of afferent fibers exiting the larynx via the superior laryngeal nerve caused respiratory phase shifts via an NST/PB feedback pathway. Both the NST and the PB appear to integrate multiple sources of somatosensory feedback from the larynx and from pulmonary stretch-activated receptors in the lungs for the purpose of regulating respiratory rhythms and triggering respiratory reflexes such as the Hering-Breuer reflex [24–27]. The PB complex, and especially the ventrolateral portions of the PB including the Kölliker-Fuse nucleus, possesses a profound influence on breathing patterns but has also been routinely implicated as a central component of the vertebrate vocal motor pathway [60, 152–154]. The PB is one of the major neuroanatomical targets of descending vocal motor commands, suggesting that it plays a central role in the integration of descending motor commands with ascending sensory cues. Pharmacological stimulation of the PB can generate phase shifts in respiratory rhythm that mirror phase shifts that occur during vocalizing [10]. Collectively these results led to the hypothesis that one of the principle roles of the PB in vocalizing may be to adapt respiratory rhythms to vocal motor commands by causing the appropriate phase shifts. This hypothesis was tested by pharmacologically inactivating the ventrolateral PB in awake, spontaneously vocalizing horseshoe bats [137].

Vocal-respiratory coordination in horseshoe bats

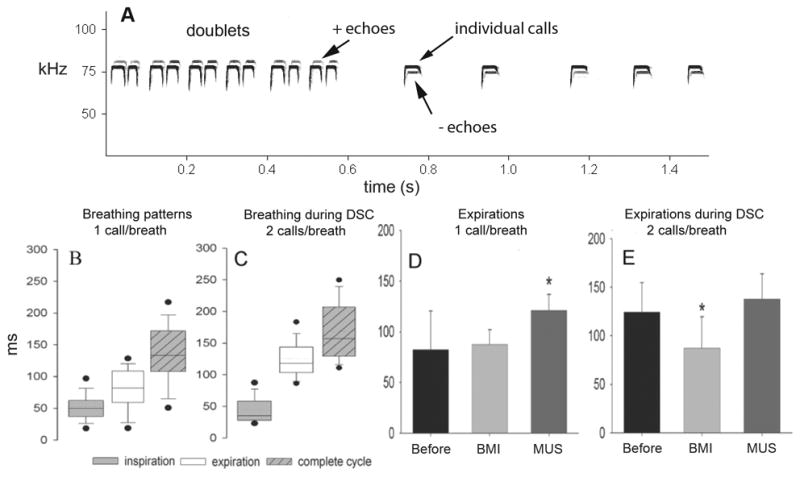

Echolocating bats integrate their echolocation pulses into their breathing patterns using strategies similar to those seen in other mammals and birds [90, 145]. Bat echolocation call structures are more highly stereotyped than the communication sounds used by other mammals, but the temporal dynamics of their vocal emissions are comparable to human speech [139]: for example, just as human speech is generated by stringing together sequences of short sounds known as formats, each representing unique combinations of constant frequencies (CF) and transient frequency modulations (FM), bats too emit rapid continuous sequences of calls possessed of flexible CF and FM components. A foraging bat usually emits one call per breath, but as the bat passes through dense foliage it increases call rate. These increases in call rate are achieved primarily by shortening the respiratory cycle (phase leads). A bat approaching its prey may secondarily switch to emitting two or more calls per breath (known as doublets or multiplets), and then proceed to conclude prey capture with the emission of a burst of calls within a single breath, the so-called feeding buzz [42, 131]. As mentioned above, horseshoe bats (Rhinolophus ferrumequinum) are unusual in that they emit relatively long echolocation calls, typically 40–50 ms [139]. For horseshoe bats, vocalizations begin and end with the onset and offset of expiration [104, 112, 144]. To briefly increase call rate horseshoe bats can either shorten the preceding inspiration duration or, as in the case of doublets or feeding buzzes, they can lengthen their expiratory durations to accommodate extended sequences of multiple calls within a single respiratory cycle (Fig. 1), thereby creating a phase lag in the breathing rhythms. One advantage of experimenting with horseshoe bats is that these different call temporal patterns and the corresponding respiratory phase shifts can be evoked from stationary bats using controlled auditory feedback [139]. Horseshoe bats exhibit a behavior known as Doppler-shift compensation (or DSC) in which they lower the frequency of their outgoing vocalizations during flight to stabilize the frequency of the returning echo to within a narrow bandwidth at which their auditory system is most sensitive [113, 130]. Flight speeds typically cause positive shifts in echo frequencies due to Doppler effects, and through DSC the horseshoe bat can effectively cancel these out. DSC performance is improved by higher call rates [115], and not surprisingly the appearance of positive shifts in echo frequencies often trigger these bats to emit two or more calls per breath rather than the usual one (Fig. 1A). It is therefore possible to trigger precise changes in both calling and breathing patterns in horseshoe bats by presenting them with artificially generated sounds that mimic natural sounding echoes shifted upwards in frequency.

Figure 1.

A) A spectrogram of horseshoe bat echolocation calls and echoes. During the first 600 ms of the record the bat was receiving electronically frequency-shifted versions of its own calls played back as echo mimics following a 4 ms delay. When the echo mimics were shifted above the bats call frequency the bat automatically emitted two calls per breath (doublets). When the echo mimics were shifted to frequencies below the bats call frequency the bat emitted only one call per breath. B and C compare the averaged breathing patterns measured in five bats while they were emitting calls spontaneously at 1 call per breath (B) or while emitting 2 calls per breath (C) while performing Doppler-shift compensation (DSC). D and E illustrate the effects of iontophoretic injections of the GABA antagonist (−)-bicuculline methiodide (BMI) and agonist muscimol hydrobromide (MUS) in the PB on expiratory durations during calling. MUS caused expirations to be longer than normal during the emission of single calls, while BMI prevented expirations from extending to accommodate emitting two calls per breath. Figure adapted from [127].

Working with awake, unanesthetized bats, we found that when GABAergic synapses in the ventrolateral PB were blocked following iontophoretic injection of the GABAA antagonist bicuculline methiodide (BMI), horseshoe bats appeared no longer able to generate the phase lags necessary for the production of doublets/multiplets (Fig. 1D,E). The production of solitary calls appeared largely unaffected, and mean call rates were not significantly unusual so long as the bats weren’t provoked to emit doublets. Alternatively, injection of the GABAA agonist muscimol hydrobromide (MUS) caused a significant extension of the expiratory duration surrounding single vocalizations that mimicked the change in breathing that normally occurred during doublet emissions, but MUS neither caused nor interfered with doublet production during DSC. From these experiments we were unable to establish whether the inhibitory inputs to the PB that delayed inspiration during extended vocal sequences came from either descending motor commands or ascending afferent feedback, or a combination of both. However, the ventrolateral PB is known to be a central relay site mediating the reflexive coordination of respiratory rhythms with locomotor activity [8, 100]: this general phenomenon known as locomotor-respiratory coupling is mediated by somatic afferent feedback to the same region of the PB in which we were able to manipulate vocal-respiratory coupling in horseshoe bats, which led us to hypothesize that vocal-respiratory coupling in mammals may rely upon somatosensory feedback from the larynx [137] to the PB via the NST. Further experiments are underway to test this hypothesis.

Auditory feedback in normal and disrupted vocalizations

Human speech exhibits a suite of rapid immediate responses to perceived changes in loudness, pitch and timing of outgoing vocalizations. One of the earliest described examples of real-time auditory influences on human speech is the Lombard effect [71, 76], which describes the reflexive increase in voice amplitude that occurs in response to increased environmental noise. The Lombard response is robust, and is not ordinarily under volitional control [93]. Perhaps most interestingly, the Lombard response includes accompanying shifts in the spectral distribution of speech energies that are different from the spectral adaptations of intentionally loud speech [75]. This vocal response now appears to represent one aspect of the more general phenomenon of voice amplitude control, as evidenced by other examples of reflexive changes in voice amplitude that can be stimulated by unanticipated perturbations in voice loudness feedback [71, 126–128]. This phenomenon, in which a speaker increases or decreases voice amplitude in response to perceived changes in voice loudness feedback, appears similarly reflexive but lends itself to more detailed analyses of the relative effects of amplitude, timing and speech context. For example, Bauer et al. found that compensatory changes in voice amplitude exhibited the greatest relative gains in response to the smallest (1dB) perturbations in feedback loudness, and response magnitudes were larger for the soft voice amplitudes than for normal voice amplitudes [4]. Loudness compensation was greater for increases than decreases in feedback loudness, and the mean compensation latency was approximately 150 ms [4, 49].

In humans, the reflexive control of speech loudness appears to follow a time course similar to the response to pitch-shifted feedback, or the pitch-shift reflex (PSR) [4, 9, 49, 72, 73, 136]. Speakers exhibit a reflexive compensatory response to perceived shifts in voice pitch which occurs with a latency of approximately 130 ms and, again, appears not to be under volitional control [4, 9, 72, 73, 136]. In a related series of experiments [52], when speakers were presented with feedback in which the formant frequency of specific vowels was electronically shifted within a subset of specific words, speakers subsequently made compensatory changes in the production of the pitch-shifted vowels not only in the test words containing the altered vowel, but also in other words containing the same vowel. Furthermore the compensatory response appeared to automatically extend to the production of other vowels that had not been electronically pitch-shifted. Thus, auditory-feedback mechanisms controlling both vocal pitch and loudness appear to have very generalized effects on normal speech production. So far very little is known about the nature of the neural substrates underlying these responses; the response latencies are theoretically long enough to allow for cortical integration mechanisms, but the rapid reflexive nature and generalized response properties seem to indicate that in some cases these responses may be mediated at a lower hierarchical level in the descending motor pathways. One clue to the neural substrate comes from evidence that pitch and loudness compensation behaviors are severely impaired in Parkinson’s disease patients, which suggests that a normally functioning interaction between the cortex and basal ganglia may be needed for auditory cues to be properly incorporated into the vocal motor pathway. [66].

The normal responses to altered auditory feedback have also been used to explore stuttering. In some humans, stuttering can be alleviated by presenting the stutterer with either pitch-shifted or delayed auditory feedback [6, 45, 62], suggesting that developmental or pathological disruptions of the normal pathways by which auditory cues are incorporated into the speech motor program may underlie some common speech disorders. However, stuttering exhibits many different etiologies and correspondingly different playback paradigms are differentially successful at reducing stuttering in different people [6, 150]. This fact prompts the assumption that there may be multiple parallel pathways by which auditory cues are hierarchically integrated into the descending vocal motor pathways, including both cortical and subcortical audio-vocal interactions.

Audio-vocal integration in bats and other mammals

Vocal behaviors like the Lombard response have been demonstrated to occur in a variety of birds [18, 78] and mammals [54, 109, 125, 135]. Echolocating bats maintain a very tight control over their voice amplitudes [42], and although the behavior has never been specifically categorized as a Lombard effect per se, background noise does cause a predictable increase in call intensity as well as other vocal adaptations [132]. Bats flying through a changing environment vary their call intensities in dynamic ways that are often coupled with changes in call durations and repetition rates [46, 50, 51]. Call intensity has a profound impact on ranging capabilities of the echolocation system, but very loud calls also carry substantial energy requirements, thus bats must efficiently regulate call intensity to match behapvioral contexts. It is well known that many bats decrease the intensity of their echolocation calls as they approach obstacles or prey [42, 59, 65, 151]. This echo intensity compensation behavior is believed to optimize echo intensities for signal analysis within the auditory system [21, 46, 69], particularly during critical phases such as prey capture and navigating through cluttered spaces.

During flight, the mustached bat and the horseshoe bat perform both intensity compensation and Doppler-shift compensation behaviors simultaneously; call intensity is decreased in response to increasing echo intensity and call frequency is decreased in response to increasing echo frequency. However, in a stationary horseshoe bat one can demonstrate that although the two behaviors occur simultaneously and with similar time courses, they are largely independent of one another. Presenting horseshoe bats with electronically pitch-shifted playback elicits compensatory changes in call frequency but not call intensity.

Frequency compensation mechanisms are sensitive to other call parameters. Doppler-shift compensation behavior is particularly sensitive to the temporal relationship between the outgoing call and the returning echo; frequency compensation performance is optimized by shorter (4–10 ms) call-delays (from the onset of the call to arrival of the echo) and longer temporal overlaps between outgoing call and returning echo [114]. Frequency compensation performance is degraded as echo intensity decreases, however it appears that this effect can be traced at least in part to a reduced capacity to discriminate changes in echo frequency at lower echo intensities [138].

Many bats switch from using relatively long, narrow bandwidth calls in open space to using short, broadband (frequency-modulated, or FM) calls when approaching targets or obstacles [110, 111, 134, 143]. In addition to intensity compensation behavior, bats also exhibit changes in the spectral and temporal parameters of their calls in response to increased environmental noise. Bats like the horseshoe bat and mustached bat use specialized constant-frequency (CF) calls because this type of call enhances resolution in cluttered spaces [89]. The Mexican free-tailed bat, Tadarida brasiliensis, automatically switches from using FM to CF-FM calls when it enters its cluttered and noisy day roosts [119, 133], also shifting the peak call intensities to the beginning rather than the ending of each call [119]. Interestingly, Tadarida makes similar transformations in call structure for both echolocative and communicative vocalizations upon entering the roost [119]. Though some of the precise changes in call structure exhibited by echolocating bats appear to have evolved specifically in support of echolocation behavior, many of the audio-vocal responses exhibited by echolocating bats have been described in other mammals, including humans. Thus, there appears to be a suite of very similar vocal responses across mammals that stabilize voice pitch, intensity and temporal dynamics in adult mammals.

Auditory feedback control of vocal pitch in horseshoe bats

While performing Doppler-shift compensation (Fig. 2A), horseshoe bats can only alter the frequency of subsequent calls, not the currently outgoing call [118]; based on estimates of the minimum necessary call-echo overlap and typical call rates during DSC [139], it is estimated that echo parameters are incorporated in subsequent call adjustments with latencies on the order of 25–30 ms. Naturally, the horseshoe bat brain is much smaller than a human brain, and so if we take for granted that response latencies reliably indicate relative axonal travel distances and the numbers of synapses involved in the sensorimotor circuit, one expects the bat’s response latencies to be a little shorter than the 150 ms latencies exhibited by humans. However, within the bat’s ascending auditory system, single neuron response latencies in the range of 20–25 ms appear as early as the midbrain inferior colliculus [97], which makes it hard to imagine that any more sophisticated and time-consuming cortical processing might be involved in the DSC behavior. Electrical stimulations of the mustached bat anterior cingulate cortex evoked echolocation calls that varied in call frequency over the same range of frequencies as those utilized during DSC [36, 37], yet surgical ablation of the so-called “DSC region” of the auditory cortex did not prevent the bats from performing DSC [34]. Where then is the main connection between the ascending auditory and descending vocal motor systems guiding the automated stabilization of echo frequencies?

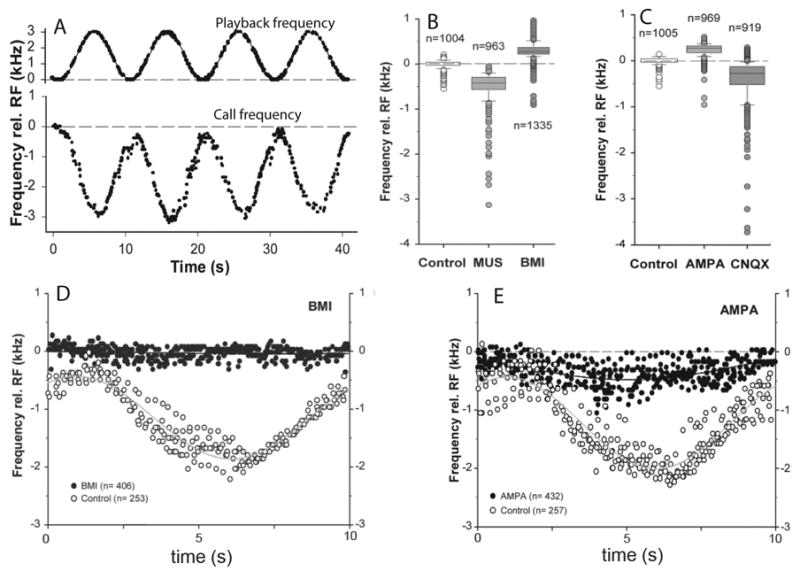

Figure 2.

A) Illustration of the Doppler-shift compensation behavior (DSC) in horseshoe bats. The bat’s call frequency (black dots, bottom trace) was recorded and electronically sinusoidally- modulated in frequency over a range of 0 to 3 kHz above the bats resting call frequency (RF) in 10 sec cycles. Each echo mimic was played back to the bat following a 4 ms delay (black dots, top trace, indicates shift in echo frequency relative to frequency of prior call). B and C illustrate the average effects of pharmacological manipulations of GABAergic (BMI, MUS., see fig 1 legend) and glutamatergic activity in the lateral PB on resting call frequencies in four bats (AMPA, α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4- propionic acid, is a non NMDA-type glutamate receptor agonist; CNQX, 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione, is an AMPA/kainate receptor agonist). In D, iontophoretic injection of BMI prevented a bat from lowering its call frequency in response to pitch-shifted echoes (same playback paradigm as in A). E illustrates the effects of AMPA on DSC performance when injected into the lateral PB. Figure adapted from[137].

The first clues about where in the horseshoe bat brain acoustic cues were being integrated with vocal motor commands during DSC came from extracellular single unit recordings of neurons located within a midbrain paralemniscal region just medial to the dorsal nucleus of the lateral lemniscus and ventral to the inferior colliculus [81, 82]. Here Metzner found subsets of neurons whose vocalization-related firing patterns were specifically influenced by the appearance of echo frequencies mimicking natural Doppler effects in a manner consistent with subsequent changes in call frequency. Surprisingly however, localized electrical or pharmacological lesions of this specific site appeared not to influence compensation performance [94]. Yet in another lesioning study in which large portions of the ventral inferior colliculus and underlying tegmentum were ablated, frequency compensation was severely impacted [86]. Using localized pharmacological manipulations of the midbrain tegmentum, we eventually found a site within the neighboring lateral parabrachial complex at which iontophoretic application of the GABAergic antagonist bicuculline methiodide (BMI) completely abolished all DSC behavior (Fig. 2D). The lateral PB is an integral component of the vocal motor pathway and also mediates basic laryngeal reflexes. Not surprisingly, pharmacological manipulations of inhibitory synapses in the lateral PB altered call frequencies even at rest (Fig 2B,C). BMI blocked DSC behavior and elevated resting call frequencies, while the GABA agonist muscimol hydrobromide (MUS) caused bats to overcompensate during DSC and lowered resting call frequencies. We hypothesized that echo frequencies returning above the outgoing call frequency lowered subsequent call frequencies via GABAergic inhibition in the lateral PB [140].

Horseshoe bats also elevate call frequency in response to echoes returning at frequencies below that of the outgoing call [84], although the compensatory response to decreases in echo frequency are smaller and the response times are greater than changes evoked by equivalent increases in echo frequency. Following our previous hypothesis, this could have been accounted for by either an acoustically-mediated reduction in the resting level of inhibitory GABAergic activity which thereby allowed an increase in call frequency to occur, or perhaps the elevated call frequencies were accounted for by the integration of an additional excitatory feedback pathway. Iontophoretic application of the Glutamatergic agonist AMPA blocked DSC at the same neuroanatomical site in which BMI also blocked DSC (Fig. 2E), and AMPA caused call frequencies at rest to increase. Application of AMPA’s antagonistic counterpart CNQX caused a lowering of call frequencies at rest (Fig. 2C) and slowed the bats return to resting frequency during DSC. These results indicated that the automatic stabilization of echo frequencies exhibited by horseshoe bats could be accounted for by the integration of parallel excitatory and inhibitory feedback inputs to a subset of neurons in the PB projecting from the neighboring ascending auditory pathway and project directly to the laryngeal motor neurons in the nucleus ambiguous [83, 140]. Whether such an audio-vocal feedback pathway exists in other animals, or even other bats, has not been explored yet.

Parallel auditory feedback pathways regulate vocal timing differently in horseshoe bats

Echolocating bats use the time delay between the outgoing call and returning echo for estimating the distance between themselves and approaching obstacles. As obstacles get closer and echoes return sooner bats call more frequently, or more specifically, shorter echo delays drive phase leads in the succeeding inter-call intervals. Stationary horseshoe bats can be stimulated to call progressively faster by shortening the time delay between the onset of their outgoing call and the onset of an electronically generated echo mimic [139]. Many bats, including the horseshoe bat, make use of short FM sweeps specifically for the purpose of improved target ranging acuity [129, 131]. For the horseshoe bat this FM component is added to both ends of their long CF calls (see Fig. 1A). We found that horseshoe bats continued to make appropriate adjustments in call rate even when the only portion of the call played back to them was the FM component [139]. Alternatively, horseshoe bats will perform DSC and switch to emitting doublets when presented with an artificially-generated CF echo mimic (a pure tone), although changing the delay of the CF echo mimic had no effect on call rates [116, 139] in the absence of an FM tail. Presumably these two temporal vocal responses are controlled independently because the CF and FM components of the call are processed separately in the horseshoe bat’s auditory system [101–103, 120, 141, 142]. Parallel processing of acoustic parameters is a typical feature of the vertebrate auditory system, and the bat’s auditory system processes complex communication sounds similarly to other mammals [68, 95, 96, 98, 99]. Generally speaking, we would like to think that acoustic temporal cues guide vocal timing and, operating in parallel, acoustic spectral cues are used to stabilize vocal pitch, but this scenario is most likely an oversimplification. Just as speech fluency is sensitive to perceived pitch in stuttering humans, the temporal dynamics of horseshoe bat vocalizations are influenced by combinations of spectral and temporal cues contained within each returning echo. Consistent with this, we may speculate that some forms of human speech disfluency may derive specifically from conflicts arising during the process of integrating multiple streams of sensory feedback during vocalizing. Evidence that pitch-shifted or delayed auditory feedback can in some circumstances successfully alleviate stuttering would seem to support such a hypothesis [45, 62]. To address these questions we need to know significantly more about where and how multiple sensory cues integrated into the mammalian vocal motor pathways.

The significance of behavioral context in audio-vocal integration

Just as there is ample evidence that stuttering is sensitive to auditory feedback, it is also well known that the severity of stuttering is heavily influenced by behavioral context [6, 150]. For example stuttering can increase in severity when speaking in front of an audience, and yet it can be alleviated in front of the same audience with choral speech, or having the stutterer speak in unison with another person [3, 63]. But the significance of specific sensory feedback cues becomes considerably more ambiguous with evidence that the ameliorating effects of choral speech can be reproduced by having a second speaker silently mouth the words [108]. Thus, stuttering in humans is certainly a complex phenomenon that involves more than simply uncoordinated feedback pathways. A large portion of the cerebral cortex is involved in normal human speech production, including extensive interactions between the temporal, parietal and frontal lobes that integrate auditory and somatosensory cues with motor commands. Yet while considerable progress has been made towards identifying regions of the cerebral cortex involved in speech motor control [43, 60, 88], there is a paucity of details concerning how sensory cues are physiologically integrated into the vocal motor pathways within the cortex. There are some significant differences in brain architecture and activity patterns between stutterers and non-stutterers, particularly in speech and language sensorimotor regions of the cortex [31, 32, 55], but whether or not these large scale differences ultimately unmask greater insight into sensory feedback control of speech remains to be seen.

Echolocating bats vocalize both for echolocation and communication. While much is known about how sensory feedback influences echolocation call structure and timing, little is known about the role of sensory feedback during the production of communication calls. . Many if not all bats emit a broad repertoire of social communications sounds, some of which closely resemble echolocation calls and some of which are totally dissimilar to and perhaps even acoustically maladaptive as echolocation calls [57, 64, 77]. Does auditory feedback influence vocalizing similarly in both echolocation and communication contexts? The answer appears to be no. In the field, big brown bats (Eptesicus fuscus) routinely use long narrow-bandwidth calls while searching for prey, but within the confined spaces of the lab this bat never emits this type of call [42, 143]. This is true as well of the Mexican free-tailed bat (Tadarida brasiliensis), which uses a very similar suite of long echolocation calls while foraging in open space but never emits long echolocation calls in the lab. But both Eptesicus fuscus and Tadarida brasiliensis utilize a complex repertoire of communication sounds within their roosts, including many varieties of long, constant frequency calls that look very similar to the long calls used while hunting in the field. In the context of communication these calls do not appear constrained by the acoustic conditions under which they are uttered. Clearly then, in the context of social communication the acoustic features of an inadvertent echo don’t carry the same weight as they do during flight. Thus, it appears that the effects of auditory feedback on vocal motor patterns must be dependent upon the behavioral context. This in turn is indicative of the kind of sophisticated vocal control mechanisms that are rarely discussed outside of human speech, and implies that there may be considerable real-time interactions occurring between the bat’s auditory and vocal motor cortices that define when sensory feedback is relevant.

Conclusions

A hierarchically organized motor control pathway controls all mammalian vocalizations. The primary challenge facing us is not identifying where in the descending motor pathways sensory feedback enters the stream of commands, because it is more likely the case that sensory cues are entering the vocal motor pathways at every stage. Rather the challenge lies in trying to understand the functional significance of multiple sensory cues within each stage of vocal motor patterning. The complexity and sophistication of human speech makes it difficult to compare our vocalizations with those uttered by other mammals, even closely related ones. Yet there is a significant suite of generalized vocal responses displayed by humans that are also exhibited by many other vocalizing mammals, and even some non-mammalian vertebrates [78]. This suggests that human vocal behaviors such as the Lombard response or the response to pitch-shifted feedback are not necessarily mediated by those unique parts of the human brain that underlie speech and language, but must instead reflect more generalized aspects of audio-vocal integration in the mammalian brain. These observations are particularly important in the context of speech disorders such as stuttering and dysarthria, because the experimental literature on this topic consistently reveals an interaction between speech fluency and a subset of surprisingly common mammalian vocal reflexes. Indeed, stuttering and other forms of vocal disfluency may turn out to be relatively common pathologies among the more vocal terrestrial vertebrates [14, 74].

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Health Grant DC007962 to MS and by Texas A&M University. I thank Walter Metzner, Kohta Kobayashi, Ma Jie, Antonio Guillén-Servent, Christine Schwartz and Jedidiah Tressler for their support, assistance and many helpful discussions. Thanks also to the Chinese Forestry Department for making the horseshoe bat research possible, to the Texas A&M University Athletic Department for access to the free-tailed bats living in Kyle Field, and to the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department for issuing the collecting permits.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Adzaku FK, Wyke B. Innervation of the subglottic mucosa of the larynx and its significance. Folia Phoniatr. 1979;31:271–283. doi: 10.1159/000264174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altringham JD. Bats: biology and behaviour. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc.; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armson J, Kalinowski J, Foote S, Witt C, Stuart A. Effect of frequency altered feedback and audience size on stuttering. Eur J Disord Commun. 1997;32:359–366. doi: 10.3109/13682829709017901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauer JJ, Mittal J, Larson CR, Hain TC. Vocal responses to unanticipated perturbations in voice loudness feedback: an automatic mechanism for stabilizing voice amplitude. J Acoust Soc Am. 2006;119(4):2363–71. doi: 10.1121/1.2173513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blom S. Afferent influences on tongue muscle activity. Acta Physiol Scand. 1960;49:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bloodstein O. A handbook on stuttering. 5. San Diego: Singular; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brahic CJ, Kelley DB. Vocal circuitry in Xenopus laevis: telencephalon to laryngeal motor neurons. J Comp Neurol. 2003;464(2):115–30. doi: 10.1002/cne.10772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bramble DM, Carrier DR. Running and breathing in mammals. Science. 1983;219:251–256. doi: 10.1126/science.6849136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burnett TA, Freedland MB, Larson CR, Hain TC. Voice F0 responses to manipulations in pitch feedback. J Acoust Soc Am. 1998;103(6):3153–61. doi: 10.1121/1.423073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chamberlin NL, Saper CB. Topographic organization of respiratory responses to glutamate microstimulation of the parabrachial nucleus in the rat. J Neurosci. 1994;14(11 Pt 1):6500–10. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-11-06500.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark KF, Farber JP. Recording from afferents in the intact recurrent laryngeal nerve during respiration and vocalization. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1998;107(9 Pt 1):753–60. doi: 10.1177/000348949810700903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clark KF, Farber JP. Effect of recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis on superior laryngeal nerve afferents during evoked vocalization. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl. 2001;187:18–31. doi: 10.1177/00034894011100s702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clark KF, Farber JP. Internal superior laryngeal nerve afferent activity during respiration and evoked vocalization in cats. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl. 2001;187:3–17. doi: 10.1177/00034894011100s701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooper BG, Goller F. Partial muting leads to age-dependent modification of motor patterns underlying crystallized zebra finch song. J Neurobiol. 2004;61(3):317–32. doi: 10.1002/neu.20062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cordes AK. Stuttering includes both within-word and between-word disfluencies. J Speech Hear Res. 1995;38:382–386. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3802.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cordes AK. Individual and consensus judgements of disfluency types in the speech of persons who stutter. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2000;43:951–964. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4304.951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cordes AK, Ingham RJ. Judgements of stuttered and nonstuttered intervals by recognized authorities in stuttering research. J Speech Hear Res. 1990;38:33–41. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3801.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cynx J, Lewis R, Tavel B, Tse H. Amplitude regulation of vocalizations in noise by a songbird, Taeniopygia guttata. Anim Behav. 1998;56(1):107–13. doi: 10.1006/anbe.1998.0746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis PJ, Nail BS. Quantitative analysis of laryngeal mechanosensitivity in the cat and rabbit. J Physiol. 1987;388:467–485. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis PJ, Zhang SP, Bandler R. Pulmonary and upper airway afferent influences on the motor pattern of vocalization evoked by excitation of the midbrain periaqueductal gray of the cat. Brain Res. 1993;607:61–80. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91490-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Denzinger A, Schnitzler HU. Echo SPL, training experience, and experimental procedure influence the ranging performance in the big brown bat, Eptesicus fuscus. J Comp Physiol A. 1998;183(2):213–24. doi: 10.1007/s003590050249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Egnor SE, Hauser MD. A paradox in the evolution of primate vocal learning. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27(11):649–54. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elman JL. Effects of frequency-shifted feedback on the pitch of vocal productions. J Acoust Soc Amer. 1981;70(1):45–50. doi: 10.1121/1.386580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ezure K, Tanaka I, Miyazaki M. Pontine projections of pulmonary slowly adapting receptor relay neurons in the cat. Neuroreport. 1998;9(3):411–4. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199802160-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feldman JL. Neurophysiology of breathing in mammals. In: Brookhart JM, Mountcastle VB, editors. Handbook of physiology; The nervous system, intrinsic regulatory systems of the brain. Bethesda: Am Physiol Soc; 1986. pp. 463–524. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feldman JL, Gautier H. Interactions of pulmonary afferents and pneumotaxic center in control of respiratory pattern in cats. J Neurophysiol. 1976;39:31–44. doi: 10.1152/jn.1976.39.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feldman JL, Mitchell GS, Nattie EE. Breathing: rhythmicity, plasticity, chemosensitivity. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2003;26:239–266. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.041002.131103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Folkins JW, Canty JL. Movements of the upper and lower lips during speech: interactions between lips with the jaw fixed at different positions. J Speech Hear Res. 1986;29(3):348–56. doi: 10.1044/jshr.2903.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Folkins JW, Zimmermann GN. Jaw-muscle activity during speech with the mandible fixed. J Acoust Soc Am. 1981;69(5):1441–5. doi: 10.1121/1.385828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Folkins JW, Zimmermann GN. Lip and jaw interaction during speech: responses to perturbation of lower-lip movement prior to bilabial closure. J Acoust Soc Am. 1982;71(5):1225–33. doi: 10.1121/1.387771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fox PT, Ingham RJ, Ingham JC, Hirsch TB, Downs JH, Martin C, Jerabek P, Glass T, Lancaster JL. A PET study of the neural systems of stuttering. Nature. 1996;382(6587):158–61. doi: 10.1038/382158a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fox PT, Ingham RJ, Ingham JC, Zamarripa F, Xiong JH, Lancaster JL. Brain correlates of stuttering and syllable production. A PET performance-correlation analysis. Brain. 2000;123 (Pt 10):1985–2004. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.10.1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fung ML, St John WM. Separation of multiple functions in the ventilatory control of pneumotaxic mechanisms. Respir Physiol. 1994;96:83–98. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(94)90108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gaioni SJ, Riquimaroux H, Suga N. Biosonar behavior of mustached bats swung on a pendulum prior to cortical ablation. J Neurophysiol. 1990;64(6):1801–17. doi: 10.1152/jn.1990.64.6.1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goodson JL, Bass AH. Vocal-acoustic circuitry and descending vocal pathways in teleost fish: convergence with terrestrial vertebrates reveals conserved traits. J Comp Neurol. 2002;448(3):298–322. doi: 10.1002/cne.10258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gooler DM, O’Neill WE. The central control of biosonar signal production in bats demonstrated by microstimulation of anterior cingulate cortex in the echolocating bat, Pteronotus parnelli parnelli. In: Newman JD, editor. The physiological control of mammalian vocalization. New York: Plenum Press; 1986. pp. 153–184. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gooler DM, O’Neill WE. Topographic representation of vocal frequency demonstrated by microstimulation of anterior cingulate cortex in the echolocating bat, Pteronotus parnelli parnelli. J Comp Physiol A. 1987;161(2):283–94. doi: 10.1007/BF00615248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gould WJ, Okamura H. Interrelationships between voice and laryngeal mucosal reflexes. In: Wyke B, editor. Ventilatory and phonotory control mechanisms. Oxford: Oxford Univeristy Press; 1974. pp. 374–369. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gracco VL. Sensorimotor mechanisms in speech motor control. In: Hultsijn PH, Starkweather W, editors. Speech motor control and stuttering. Amsterdam: North Holland/Elsevier; 1991. pp. 53–78. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gracco VL, Abbs JH. Sensorimotor characteristics of speech motor sequences. Exp Brain Res. 1989;75:586–598. doi: 10.1007/BF00249910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gracco VL, Löfqvist A. Speech motor coordination and control: evidence from lip, jaw and laryngeal movements. J Neurosci. 1994;14:6585–6597. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-11-06585.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Griffin DR. Listening in the dark; the acoustic orientation of bats and men. New Haven; Yale University Press: 1958. p. 208. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guenther FH. Cortical interactions underlying the production of speech sounds. J Commun Disord. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2006.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hardcastle WJ. Physiology of speech production. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hargrave S, Kalinowski J, Stuart A, Armson J, Jones K. Effects of frequency-altered feedback on stuttering frequency at normal and fast speech rates. J Speech Hear Res. 1994;37:1313–1319. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3706.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hartley DJ, Campbell KA, Suthers RA. The acoustic behavior of the fish-catching bat, Noctilio leporinus, during prey capture. J Acoust Soc Am. 1989;86:8–27. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hartley DJ, Suthers RA. The acoustics of the vocal tract in the horseshoe bat, Rhinolophus hildebrandti. J Acoust Soc Am. 1988;84:1201–1213. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hayakawa T, Takanaga A, Maeda S, Seki M, Yajima Y. Subnuclear distribution of afferents from the oral, pharyngeal and laryngeal regions in the nucleus tractus solitarii of the rat: a study using transganglionic transport of cholera toxin. Neurosci Res. 2001;39(2):221–32. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(00)00218-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heinks-Maldonado TH, Houde JF. Compensatory responses to brief perturbations of speech amplitude. ARLO. 2005;6:131–137. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Holderied MW, Helversen Ov. Echolocation range and wingbeat period match in aerial-hawking bats. Proc Royal Soc Lond B. 2003;270:2293–2299. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2003.2487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Holderied MW, Korine C, Fenton MB, Parsons S, Robson S, Jones G. Echolocation call intensity in the aerial hawking bat Eptesicus bottae (Vespertilionidae) studied using stereo videogrammetry. J Exp Biol. 2005;208:1321–1327. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Houde JF, Jordan MI. Sensorimotor adaptation in speech production. Science. 1998;279(5354):1213–6. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5354.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hsiao TY, Solomon NP, Luschei ES, Titze IR, Liu K, Fu TC, Hsu MM. Effect of subglottic pressure on fundamental frequency of the canine larynx with active muscle tensions. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1994;103:817–821. doi: 10.1177/000348949410301013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Insley SJ, Southall BL. Source levels of northern elephant seal vocalizations in air. J Acoust Soc Am. 2005;118:2018–2019. doi: 10.1121/1.5139422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jäncke L, Hänggi J, Steinmetz H. Morphological brain differences between adult stutterers and non-stutterers. BMC Neurol. 2004 doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-4-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Janik VM. Whistle matching in wild bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) Science. 2000;289(5483):1355–7. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5483.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Janik VM, Slater PJB. Vocal learning in mammals. In: Slater PJB, et al., editors. Advances in the Study of Behavior. Vol. 26. San Diego, California, USA; London, England, UK: Academic Press, Inc.; 1997. pp. 59–99. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jarvis ED, Gunturkun O, Bruce L, Csillag A, Karten H, Kuenzel W, Medina L, Paxinos G, Perkel DJ, Shimizu T, Striedter G, Wild JM, Ball GF, Dugas-Ford J, Durand SE, Hough GE, Husband S, Kubikova L, Lee DW, Mello CV, Powers A, Siang C, Smulders TV, Wada K, White SA, Yamamoto K, Yu J, Reiner A, Butler AB. Avian brains and a new understanding of vertebrate brain evolution. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6(2):151–9. doi: 10.1038/nrn1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jen PH-S, Kamada T. Analysis of orientation signals emitted by the CF-FM bat, Eptesicus fuscus during avoidance of moving and stationary obstacles. J Comp Physiol. 1982;148:389–398. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jürgens U. Neural pathways underlying vocal control. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2002;26(2):235–58. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(01)00068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jürgens U, Kirzinger A. The laryngeal sensory pathway and its role in phonation. A brain lesioning study in the squirrel monkey. Exp Brain Res. 1985;59(1):118–24. doi: 10.1007/BF00237672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kalinowski J, Armson J, Roland-Mieszkowski M, Stuart A, Gracco VL. Effects of alterations in auditory feedback and speech rate on stuttering frequency. Lang Speech. 1993;36:1–16. doi: 10.1177/002383099303600101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kalinowski J, Saltuklaroglu T. Choral speech: the amelioration of stuttering via imitation and the mirror neuronal system. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2003;27(4):339–47. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(03)00063-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kanwal JS, Matsumura S, Ohlemiller K, Suga N. Analysis of acoustic elements and syntax in communication sounds emitted by mustached bats. J Acoust Soc Am. 1994;96(3):1229–54. doi: 10.1121/1.410273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kick SA, Simmons JA. Automatic gain control in the bat’s sonar receiver and the neuroethology of echolocation. J Neurosci. 1984;4(11):2725–37. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-11-02725.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kiran S, Larson CR. Effect of duration of pitch-shifted feedback on vocal responses in patients with Parkinson’s disease. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2001;44(5):975–87. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2001/076). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kittelberger JM, Land BR, Bass AH. Midbrain periaqueductal gray and vocal patterning in a teleost fish. J Neurophysiol. 2006;96(1):71–85. doi: 10.1152/jn.00067.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Klug A, Bauer EE, Hanson JT, Hurley L, Meitzen J, Pollak GD. Response selectivity for species-specific calls in the inferior colliculus of Mexican free-tailed bats is generated by inhibition. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88(4):1941–54. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.88.4.1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kobler JB, Wilson BS, Henson OW, Jr, Bishop AL. Echo intensity compensation by echolocating bats. Hear Res. 1985;20(2):99–108. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(85)90161-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kuhl PK. Early language acquisition: cracking the speech code. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5(11):831–43. doi: 10.1038/nrn1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lane H, Tranel R. The lombard sign and the role of hearing in speech. J Speech Hear Res. 1971;14:677–709. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Larson CR, Burnett TA, Bauer JJ, Kiran S, Hain TC. Comparison of voice F0 responses to pitch-shift onset and offset conditions. J Acoust Soc Am. 2001;110(6):2845–8. doi: 10.1121/1.1417527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Larson CR, Burnett TA, Kiran S, Hain TC. Effects of pitch-shift velocity on voice Fo responses. J Acoust Soc Am. 2000;107(1):559–64. doi: 10.1121/1.428323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Leonardo A, Konishi M. Decrystallization of adult birdsong by perturbation of auditory feedback. Nature. 1999;399(6735):466–70. doi: 10.1038/20933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Letowski T, Frank T, Caravella J. Acoustical properties of speech produced in noise presented through supra-aural earphones. Ear Hear. 1993;14(5):332–8. doi: 10.1097/00003446-199310000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lombard E. Le signe de l’élévation de la voix. Ann Malad l’Orielle Larynx Nez Pharynx. 1911;37:101–119. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ma J, Kobayasi K, Zhang S, Metzner W. Vocal communication in adult greater horseshoe bats, Rhinolophus ferrumequinum. J Comp Physiol A. 2006;192(5):535–50. doi: 10.1007/s00359-006-0094-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Manabe K, Sadr EI, Dooling RJ. Control of vocal intensity in budgerigars (Melopsittacus undulatus): differential reinforcement of vocal intensity and the Lombard effect. J Acoust Soc Am. 1998;103(2):1190–8. doi: 10.1121/1.421227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.McClean MD, Tasko SM. Association of orofacial with laryngeal and respiratory motor output during speech. Exp Brain Res. 2002;146(4):481–9. doi: 10.1007/s00221-002-1187-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.McCowan B, Reiss D. Vocal learning in captive bottlenose dolphins: a comparison with humans and nonhuman animals. In: Snowdon CT, Hausberger M, editors. Social influences on vocal development. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ Press; 1997. pp. 178–207. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Metzner W. A possible neuronal basis for Doppler-shift compensation in echo-locating horseshoe bats. Nature. 1989;341(6242):529–32. doi: 10.1038/341529a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Metzner W. An audio-vocal interface in echolocating horseshoe bats. J Neurosci. 1993;13(5):1899–915. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-05-01899.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Metzner W. Anatomical basis for audio-vocal integration in echolocating horseshoe bats. J Comp Neurol. 1996;368(2):252–69. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960429)368:2<252::AID-CNE6>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Metzner W, Zhang SY, Smotherman MS. Doppler-shift compensation behavior in horseshoe bats revisited: auditory feedback controls both a decrease and an increase in call frequency. J Exp Biol. 2002;205:1607–1616. doi: 10.1242/jeb.205.11.1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Moga HH, Caper CB. Connections of the parabrachial nucleus with the nucleus of the solitary tract and the medullary reticular formation in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1990;293:540–580. doi: 10.1002/cne.902930404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Movchan EV. Effects of destruction of the inferior colliculus on function of the echolocation system in horseshoe bats. Neirofiziologiya. 1980;12(4):375–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Munhall KG, Löfqvist A, Kelso JA. Lip-larynx coordination in speech: effects of mechanical perturbations to the lower lip. J Acoust Soc Am. 1994;95(6):3605–16. doi: 10.1121/1.409929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Murphy K, Corfield DR, Guz A, Fink GR, Wise RJS, Harrison J, Adams L. Cerebral areas associated with motor control of speech in humans. J Appl Physiol. 1997;83:1438–1447. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.83.5.1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Neumann I, Schuller G. Spectral and temporal gating mechanisms enhance the clutter rejection in the echolocating bat, Rhinolophus rouxi. J Comp Physiol A. 1991;169(1):109–16. doi: 10.1007/BF00198177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Neuweiler G. The biology of bats. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Niemi M, Laaksonen JP, Vahatalo K, Tuomainen J, Aaltonen O, Happonen RP. Effects of transitory lingual nerve impairment on speech: an acoustic study of vowel sounds. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;60(6):647–52. 653. doi: 10.1053/joms.2002.33113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Okamura H, Katto Y. Fine structure of muscle spindle in interarytenoid muscle of human larynx. In: Fujimura O, editor. Vocal fold physiology: voice production, mechanisms and functions. New York: Raven Press; 1988. pp. 135–143. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pick HL, Jr, Siegel GM, Fox PW, Garber SR, Kearney JK. Inhibiting the Lombard effect. J Acoust Soc Am. 1989;85(2):894–900. doi: 10.1121/1.397561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Pillat J, Schuller G. Audiovocal behavior of Doppler-shift compensation in the horseshoe bat survives bilateral lesion of the paralemniscal tegmental area. Exp Brain Res. 1998;119(1):17–26. doi: 10.1007/s002210050315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pollak GD, Burger RM, Klug A. Dissecting the circuitry of the auditory system. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26(1):33–9. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(02)00009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Pollak GD, Klug A, Bauer EE. Processing and representation of species-specific communication calls in the auditory system of bats. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2003;56:83–121. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(03)56003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pollak GD, Schuller G. Tonotopic organization and encoding features of single units in inferior colliculus of horseshoe bats: functional implications for prey identification. J Neurophysiol. 1981;45(2):208–26. doi: 10.1152/jn.1981.45.2.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Popper AN, Fay RR, editors. Springer handbook of auditory research. Vol. 2. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1992. The Mammalian auditory pathway: neurophysiology; pp. xi–431. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Popper AN, Fay RR. Springer handbook of auditory research. Vol. 5. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1995. Hearing by bats; pp. xii–515. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Potts JT, Rybak IA, Paton JFR. Respiratory rhythm entrainment by somatic afferent stimulation. J Neurosci. 2005;25:1965–1978. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3881-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Radtke-Schuller S. Neuroarchitecture of the auditory cortex in the rufous horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus rouxi) Anat Embryol (Berl) 2001;204(1):81–100. doi: 10.1007/s004290100191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Radtke-Schuller S, Schuller G. Auditory cortex of the rufous horseshoe bat: 1. Physiological response properties to acoustic stimuli and vocalizations and the topographical distribution of neurons. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;7(4):570–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1995.tb00662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Radtke-Schuller S, Schuller G, O’Neill WE. Thalamic projections to the auditory cortex in the rufous horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus rouxi). II. Dorsal fields Anat Embryol (Berl) 2004;209(1):77–91. doi: 10.1007/s00429-004-0425-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rübsamen R, Schuller G. Laryngeal nerve activity during pulse emission in the CF-FM bat, Rhinolophus ferrumequinum. II. The recurrent laryngeal nerve. J Comp Physiol A. 1981;143:323–27. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rybak IA, Shevtsova NA, Paton JFR, Dick TE, St John WM, Mörschelm M, Dutscmann M. Modeling the ponto-medullary respiratory network . Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2004;143:307–319. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2004.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Rybak IA, Shevtsova NA, Paton JFR, Pierrefiche O, St John WM, Haji A. Modeling respiratory rhythmogenesis: focus on phase-switching mechanisms. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2004;551:189–194. doi: 10.1007/0-387-27023-x_29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sakamoto T, Nonaka S, Katada A. Control of respiratory muscles during speech and vocalization. In: Miller AD, Bianchi AL, Bishop BP, editors. Neural control of the respiratory muscles. New York: CRC Press; 1997. pp. 249–258. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Saltuklaroglu T, Dayalu VN, Kalinowski J, Stuart A, Rastatter MP. Say it with me: stuttering inhibited. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2004;26(2):161–8. doi: 10.1076/jcen.26.2.161.28090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Scheifele PM, Andrew S, Cooper RA, Darre M, Musiek FE, Max L. Indication of a Lombard vocal response in the St. Lawrence River Beluga. J Acoust Soc Am. 2005;117(3 Pt 1):1486–92. doi: 10.1121/1.1835508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Schnitzler H-U, Kalko EKV. Echolocation by insect-eating bats. BioSci. 2001;51:557–569. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Schnitzler H-U, Moss CF, Denziger A. From spatial orientation to food acquisition in echolocating bats. TIEE. 2003;18(8):386–394. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Schnitzler HU. Die Ultraschallortungslaute der Hufeisennasen-Fledermäuse (Chiroptera, Rhinolophidae) in verschiedenen Orientierungssituationen. Z Vergl Physiol. 1968;57:376–408. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Schnitzler HU. Control of Doppler shift compensation in the Greater Horseshoe Bat, Rhinolophus ferrumequinum. J Comp Physiol. 1973;82:79–92. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Schuller G. Echo delay and overlap with emitted orientation sounds and Doppler-shift compensation in the bat, Rhinolophus ferrumequinum. J Comp Physiol. 1977;114:103–14. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Schuller G. Influence of echolocation pulse rate on Doppler-shift compensation control system in the Greater Horseshoe Bat. J Comp Physiol A. 1986;158:239–46. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Schuller G, Beuter K, Schnitzler HU. Response to frequency-shifted artificial echoes in the bat, Rhinolophus ferrumequinum. J Comp Physiol. 1974;89:275–86. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Schuller G, Radtke-Schuller S. Neural control of vocalization in bats: mapping of brainstem areas with electrical microstimulation eliciting species-specific echolocation calls in the rufous horseshoe bat. Exp Brain Res. 1990;79(1):192–206. doi: 10.1007/BF00228889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Schuller G, Suga N. Storage of Doppler-shift information in the echolocation system of the ‘CF-FM’ bat, Rhinolophus ferrumequinum. J Comp Physiol. 1976;105:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Schwartz C, Tressler J, Keller H, Vanzant M, Ezell S, Smotherman M. The tiny difference between foraging and communication buzzes uttered by the mexican free-tailed bat, Tadarida brasiliensis. J Comp Physiol A. 2007 doi: 10.1007/s00359-007-0237-7. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Schweizer H. The connection of the inferior colliculus and the organization of the brain stem auditory system in the Greater Horseshoe Bat, Rhinolophus ferrumequinum. J Comp Neurol. 1981;201:25–49. doi: 10.1002/cne.902010104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Scott CM, Ringel RL. Articulation without oral sensory control. J Speech Hear Res. 1971;14(4):804–18. doi: 10.1044/jshr.1404.804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Shiba K, Yoshida K, Miura T. Functional roles of the superior laryngeal nerve afferents in electrically induced vocalization in anesthetized cats. Neurosci Res. 1995;20:23–30. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(95)00877-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Shiba K, Yoshida K, Nakazawa K, Konno A. Influences of laryngeal afferent inputs on intralaryngeal muscle activity during vocalization in the cat. Neurosci Res. 1997;27:85–92. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(96)01136-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Shigenaga Y, Chen IC, Suemune S, Nishimori R, Natsution D, Yoshida A, Sato H, Okamoto T, Sera M, Hosoi M. Oral and facial representation within the medullary and upper cervical dorsal horns in the cat. J Comp Neurol. 1986;243:388–408. doi: 10.1002/cne.902430309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Shipley C, Buchwald JS, Carterette EC. The role of auditory feedback in the vocalizations of cats. Exp Brain Res. 1988;69(2):431–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00247589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Siegel GM, Kennard KL. Lombard and sidetone amplification effects in normal and misarticulating children. J Speech Hear Res. 1984;27(1):56–62. doi: 10.1044/jshr.2701.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Siegel GM, Pick HL., Jr Auditory feedback in the regulation of voice. J Acoust Soc Am. 1974;56(5):1618–24. doi: 10.1121/1.1903486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Siegel GM, Schork EJ, Jr, Pick HL, Jr, Garber SR. Parameters of auditory feedback. J Speech Hear Res. 1982;25(3):473–5. doi: 10.1044/jshr.2503.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Simmons JA. The resolution of target range by echolocating bats. J Acoust Soc Amer. 1973;54(1):157–73. doi: 10.1121/1.1913559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Simmons JA. Response of the Doppler echolocation system in the bat, Rhinolophus ferrumequinum. J Acoust Soc Am. 1974;56(2):672–82. doi: 10.1121/1.1903307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Simmons JA, Grinnell AC. The performance of echolocation: acoustic images perceived by echolocating bats. In: Nachtigall PE, Moore PWB, editors. Animal Sonar: processes and performance. New York: Plenum; 1988. pp. 353–386. [Google Scholar]

- 132.Simmons JA, Lavender WA, Lavender BA. Proceedings of the Fourth International Bat Research Conference. Kenya: Kenya Literature Bureau; 1978. Adaptation of echolocation to environmental noise by the bat Eptesicus fuscus. [Google Scholar]

- 133.Simmons JA, Lavender WA, Lavender BA, Childs JE, Hulebak K, Rigden MR, Sherman J, Woolman B. Echolocation by free-tailed bats (Tadarida) J Comp Physiol A. 1978;125:291–299. [Google Scholar]

- 134.Simmons JA, Stein RA. Acoustic imaging in bat sonar: Echolocation signals and the evolution of echolocation. J Comp Physiol. 1980;135:61–84. [Google Scholar]

- 135.Sinnott JM, Stebbins WC, Moody DB. Regulation of voice amplitude by the monkey. J Acoust Soc Am. 1975;58:412–414. doi: 10.1121/1.380685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Sivasankar M, Bauer JJ, Babu T, Larson CR. Voice responses to changes in pitch of voice or tone auditory feedback. J Acoust Soc Am. 2005;117(2):850–7. doi: 10.1121/1.1849933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]