Abstract

High-magnitude and long-duration abstinence reinforcement can promote drug abstinence but can be difficult to finance. Employment may be a vehicle for arranging high-magnitude and long-duration abstinence reinforcement. This study determined if employment-based abstinence reinforcement could increase cocaine abstinence in adults who inject drugs and use cocaine during methadone treatment. Participants could work 4 hr every weekday in a workplace where they could earn about $10.00 per hour in vouchers; they were required to provide routine urine samples. Participants who attended the workplace and provided cocaine-positive urine samples during the initial 4 weeks were invited to work 26 weeks and were randomly assigned to an abstinence-and-work (n = 28) or work-only (n = 28) group. Abstinence-and-work participants had to provide urine samples showing cocaine abstinence to work and maintain maximum pay. Work-only participants could work independent of their urinalysis results. Abstinence-and-work participants provided more (p = .004; OR = 5.80, 95% CI = 2.03–16.56) cocaine-negative urine samples (29%) than did work-only participants (10%). Employment-based abstinence reinforcement can increase cocaine abstinence.

Keywords: contingency management, abstinence reinforcement, cocaine addiction, methadone, drug abuse treatment, employment

Abstinence reinforcement interventions have proven highly effective in promoting abstinence from most commonly abused drugs and in diverse populations (Higgins & Silverman, 1999). With these interventions, individuals who use drugs persistently receive desirable consequences contingent on providing objective evidence of drug abstinence. Voucher-based abstinence reinforcement has been particularly effective (Higgins, Heil, & Lussier, 2004; Lussier, Heil, Mongeon, Badger, & Higgins, 2006). Although highly effective, it appears that abstinence reinforcement interventions have not been used widely in clinical practice (McGovern, Fox, Xie, & Drake, 2004; Willenbring, Hagedorn, Postier, & Kenny, 2004).

Most research that has focused on the dissemination of abstinence reinforcement interventions has attempted to develop interventions that could be incorporated into community drug abuse treatment programs. Given the limited resources available in those programs (McLellan, Carise, & Kleber, 2003), these interventions have used reinforcers that are readily available (e.g., Stitzer, Iguchi, & Felch, 1992), have used relatively low-cost reinforcers (e.g., Pierce et al., 2006), have devised creative ways to pay for those reinforcers (e.g., Donatelle, Prows, Champeau, & Hudson, 2000), and have arranged only short-term exposure to the abstinence reinforcement interventions. These interventions have been shown to be effective and should be invaluable tools in the treatment of drug addiction. However, none of these interventions have been effective in all patients, and none have reliably produced effects that persist after the intervention ends. Additional or enhanced interventions will undoubtedly be needed to augment clinic-based abstinence reinforcement interventions.

The effectiveness of abstinence reinforcement interventions appears to be related to a simple but potentially costly parameter of the intervention: reinforcement magnitude (Dallery, Silverman, Chutuape, Bigelow, & Stitzer, 2001; Petry et al., 2004; Silverman, Chutuape, Bigelow, & Stitzer, 1999; Stitzer & Bigelow, 1984). Studies in treatment-resistant adults with highly persistent cocaine use show that the magnitudes required to promote abstinence in many patients can be very high, as much as almost $1,800 per month (Dallery et al.; Silverman et al., 1999).

The maintenance of the abstinence effects over time appears to be related to another potentially costly parameter of the intervention: duration of the abstinence reinforcement contingency. Similar to other drug abuse treatments (McLellan, Lewis, O'Brien, & Kleber, 2000), studies in some populations have shown that many patients relapse when the intervention is discontinued (e.g., Silverman et al., 1996, 1999). However, sustaining the abstinence reinforcement contingency over time can prevent relapse, at least as long as the intervention is in effect (Silverman, Robles, Mudric, Bigelow, & Stitzer, 2004). Some studies in primary cocaine-dependent patients have demonstrated clear long-term effects that are evident well after the abstinence reinforcement intervention is discontinued (Higgins, Wong, Badger, Ogden, & Datona, 2000). However, even those impressive posttreatment effects appear to be related to the duration of abstinence achieved during treatment (Higgins, Badger, & Budney, 2000). Presumably, longer duration abstinence interventions should produce longer periods of sustained abstinence, which should translate to higher rates of posttreatment abstinence.

The requirement for high-magnitude and long-duration abstinence reinforcement raises an obvious practical problem: How can such interventions be financed? One potential solution to this problem is to identify high-magnitude and sustainable reinforcers that are available in the community and could be harnessed for therapeutic purposes. In this vein, a few investigators have attempted to integrate abstinence reinforcement contingencies into employment settings and use wages for work to reinforce abstinence (Cohen, Bigelow, Hargett, Allen, & Halsted, 1973; Crowley, 1986; Milby et al., 1996; Miller, 1975; Silverman, Svikis, Robles, Stitzer, & Bigelow, 2001). These interventions have been used in regular employment settings (Cohen et al.; Crowley) and in supported work environments designed to provide paid training and supported employment to unskilled and chronically unemployed individuals (Milby et al.; Miller; Silverman et al., 2001). The interventions have varied, but all have arranged access to paid employment contingent on biologically verified drug abstinence. Patients exposed to the interventions could work and earn salary or wages, but only as long as they remained abstinent from drugs. Although employment-based abstinence reinforcement has been applied and described in prior research, the experimental analysis of employment-based abstinence reinforcement began only recently. Some early studies described employment-based abstinence reinforcement interventions but did not experimentally evaluate the interventions (Cohen et al.; Crowley). Other studies experimentally evaluated a multicomponent treatment that included an employment-based abstinence reinforcement element, but did not examine the specific effects of the employment-based abstinence reinforcement element on abstinence outcomes (Milby et al.; Miller).

Silverman et al. (2001) developed and experimentally evaluated a therapeutic workplace intervention that used employment-based abstinence reinforcement for chronically unemployed, pregnant and recently postpartum women who persisted in using heroin and cocaine during methadone treatment. These women were randomly assigned to a therapeutic workplace or usual care control group. Therapeutic workplace participants were hired and paid to work in a model supported workplace and were required to provide drug-free urine samples to work and earn wages. Therapeutic workplace participants achieved about twice the rate of abstinence from opiates and cocaine compared to the usual care control participants during the first 6 months of the study (Silverman et al., 2001), and those effects were maintained for 3 years after intake (Silverman et al., 2002).

The therapeutic workplace intervention had two features that may have influenced outcome: employment and the employment-based abstinence reinforcement contingency. In a population that was consistently unemployed (Silverman et al., 2002), simply providing employment may have increased abstinence. Employment is generally correlated with reduced drug use and is frequently thought to be a means of increasing abstinence (Magura, Staines, Blankertz, & Madison, 2004; Platt, 1995). To examine the specific benefit of arranging abstinence-contingent access to the workplace, the current study compared the effects of employment in a therapeutic workplace with and without the employment-based abstinence reinforcement contingency.

The current study was conducted in adults who injected drugs and who persisted in using cocaine despite exposure to standard community methadone-treatment services. Cocaine use by injection drug users in methadone treatment is a widespread problem (Hser, Anglin, & Fletcher, 1998) that has been associated with an increased risk of HIV infection (Chaisson et al., 1989; Schoenbaum et al., 1989) and has been difficult to treat effectively with conventional treatment approaches (Hser et al., 1998; Silverman et al., 1998). Participants were initially invited to attend the workplace independent of their urinalysis results. Participants who attended the workplace and provided cocaine-positive urine samples during a 4-week baseline were invited to attend the workplace for 26 weeks and were randomly assigned to the abstinence-and-work or work-only group. Participants in the abstinence-and-work group were required to provide urine samples that documented recent cocaine abstinence to gain and maintain access to the workplace and to continue earning the maximum pay rate. Participants in the work-only group were allowed to work in the workplace independent of their urinalysis results. Contrary to common conceptions of the effects of employment on drug use, we expected that participants would continue to use cocaine at high rates during the work-only condition. Employment can fill some of an individual's day with a nondrug activity, but drug use can take a relatively short amount of time each day, and employed individuals can easily find time to use drugs while employed. Indeed, drug use frequently occurs at high rates in individuals who are employed (see Silverman & Robles, 1999, for a detailed discussion as to why employment alone might not produce substantial reductions in drug use). We expected that participants in the abstinence-and-work group who were exposed to the employment-based abstinence reinforcement contingency would achieve the highest rates of cocaine abstinence.

Method

Setting and Materials

This study was conducted at the Center for Learning and Health, a treatment-research unit at the Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center. The therapeutic workplace included a workplace sign-in station, a urinalysis laboratory, and three workrooms (and associated staff space) where training occurred. When participants arrived at the workplace each day, they reported to the workplace sign-in station located at the entrance to the urinalysis laboratory. Staff sat on the laboratory side of the entrance at the workplace sign-in station desk, which was equipped with a personal computer and electronic barcode reader.

Urine and breath samples were collected and tested in the urinalysis laboratory. Breath samples were tested for alcohol with the AlcoSensor III. Women provided urine samples directly into commode specimen containers that were placed directly on the toilet. The urine samples were then temperature tested and transferred to storage cups. Men provided samples directly into paper cups, which were then temperature tested and transferred to storage cups. All urine samples were temperature tested using an F-1500 electronic thermometer. The urinalysis laboratory contained an Abbott AxSYM® immunoassay system for urine testing. The AxSYM® employs fluorescent polarization immunoassay technology.

Participants received the therapeutic workplace training programs in three workrooms (a total of 161 m2) that contained a total of 47 individual three-sided workstations (155 cm tall by 64 cm deep by 126 cm wide). Each workstation was equipped with a desktop (60 cm deep by 121 cm wide); a height-adjustable chair with arms; and a personal computer, keyboard, and mouse. Keyboards were covered with removable plastic covers that were painted black so that the letters on the keys could not be read while typing. Each participant was given a water bottle, headphones for listening to music CDs during training on the personal computer, a cooler for storing lunch, and picture frames to personalize the workstation.

The three workrooms opened into a central area (31 m2) where the workroom assistants sat to monitor the activities of participants. Participants had to pass through the central staff area to enter and leave the workrooms. The central area was equipped with three desks, each with a personal computer. Each desk also was equipped with an electronic barcode slot reader.

All of the participant and staff computers were interconnected through a high-speed line to central servers. All of the typing, keypad, and data-entry training programs; monitoring of the work time and earnings; and the voucher system were controlled by a custom Web-based therapeutic workplace software application program that resided on one of the servers (Silverman et al., 2005).

Recruitment and Participant Selection

The Western Institutional Review Board approved this study. Participants were enrolled in this study from April 2003 to November 2003. To recruit participants, fliers and letters were distributed to 11 Baltimore methadone programs inviting unemployed adults in methadone treatment to apply to enroll in a study that provided job-skills training and monetary vouchers. Research staff also visited the methadone treatment programs to describe the study to methadone treatment staff (e.g., counselors).

Interested individuals who approached or called research staff first completed an anonymous brief screening interview in which they were asked eight questions designed to determine quickly if they might be eligible for the study. Some of the questions were added to conceal the eligibility requirements. The interview asked the individual's age, marital status, employment status, drugs and routes of administration used in the past 30 days, what type of drug abuse treatment he or she currently receives, whether he or she receives welfare benefits, how much he or she earned through employment in the past 30 days, and whether he or she has any of several medical conditions (e.g., asthma, HIV). Brief screening interviews were conducted over the phone, in person at the methadone treatment programs, or in person at the Center for Learning and Health. Applicants were invited to participate in a full screening interview if they reported that they were 18 years or older, were unemployed, injected heroin or cocaine, used cocaine or crack in the past 30 days, and if they were currently enrolled in methadone maintenance treatment.

Full Screening Interview

At the beginning of the full screening interview, participants were invited to sign the initial screening consent form. Participants were required to pass (≥ 70% correct) a written quiz about the details of the consent form to participate. Participants were also required to read a paragraph of the consent form aloud and to read at least 80% of the words correctly to continue in the full screening interview. (This reading requirement was imposed by the institutional review board, but only 2 applicants were excluded for failing to pass this reading test.) Participants were also asked to sign a release-of-information form to allow their methadone treatment programs to provide information (e.g., current methadone dose) to our research staff.

The full interview included urine and breath samples collected under observation that were tested for cocaine, opiates, benzodiazepines, amphetamines, and alcohol; the DSM checklist (Hudziak et al., 1993), which provides a tentative assessment of whether participants met DSM criteria for cocaine, opioid, and alcohol dependence; the Addiction Severity Index Lite (ASI Lite; McLellan et al., 1985), a structured clinical interview designed to assess psychosocial functioning in seven areas commonly affected by drug use; the Risk Assessment Battery (RAB; Navaline et al., 1994), a 41-item self-report questionnaire that assesses needle use practices and sexual behaviors associated with HIV transmission; the Vocational/Educational Assessment (VEA; Zanis, Coviello, Alterman, & Appling, 2001), a 51-item questionnaire designed to gather employment-related information, including employment attitudes and experience; the welfare-to-work edition of the Treatment Services Review (TSR; McLellan, Alterman, Cacciola, Metzger, & O'Brien, 1992), a structured clinical interview designed to assess recent treatment services that participants had received; an injection track mark form to record visible injection marks; a checklist to identify physical limitations that would limit the participant's ability to type; and a contact information form, which asked participants to list contacts who we could call or write to help locate them for follow-up assessments and other research-related issues. The track mark assessment first asked the participant where he or she injected and when was the last time he or she injected, and then required the staff person to record whether or not track marks were visible, whether visible marks were red and swollen, and where the marks were located. The physical limitations checklist asked participants if they could use all of their fingers to type and if they had received medical advice not to type or engage in other repetitive finger or hand motions. This checklist also required the staff person to look for a cast on the participant's hand, to look for any visible abnormality that might prevent typing, and to determine if the participant had all of his or her fingers and thumbs. Participants were paid $30 in vouchers for completing the full interview.

To be eligible for the study, participants had to be least 18 years of age; enrolled in methadone maintenance (verified by the program); provide a cocaine-positive urine sample; report being unemployed (i.e., no days of taxable part-time or full-time employment, and earned no more than $200 in income that was not reported to the Internal Revenue Service); report using cocaine and intravenous drugs in the past 30 days; and show visible injection track marks. Participants were excluded if they reported current suicidal ideation or hallucinations. Eligible participants were invited to sign the main study consent form and participate in baseline.

Baseline

Eligible participants were invited to attend the workplace for 4 hr every weekday for 8 weeks. Mandatory urine samples were collected prior to work every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. All samples were tested for cocaine and opiates. During the first 4 weeks, participants could attend the workplace independent of their urinalysis results and could earn a base pay of $8.00 per hour plus pay for performance on training programs. To encourage brief breaks, participants could earn 5 min of paid break for every 55 min worked. Pay was earned in vouchers exchangeable for goods and services. At the end of baseline, participants who attended the workplace at least 50% of the workdays, provided at least two cocaine-positive urine samples, and were still enrolled in methadone treatment were invited to participate in the main randomized controlled portion of the study. Other participants could continue to work for 4 additional weeks but were required to provide urine samples that indicated recent abstinence from opiates and cocaine to work.

Experimental Design and Groups

Stratification and Random Assignment

Participants enrolled in the main study (N = 56) were randomly assigned to the work-only (n = 28) or abstinence-and-work (n = 28) group. Immediately prior to actual assignment, a study coordinator, who did not have direct contact with participants, randomized participants using a computer program and a stratification procedure (similar to Silverman et al., 2004) based on (a) whether 75% or more of the participant's baseline urine samples tested positive for cocaine, and (b) whether 100% of the participant's baseline urine samples tested positive for cocaine.

Study Groups

Both groups were invited to attend the workplace throughout the 26-week intervention period. Participants in both groups continued to provide mandatory urine samples and could earn base and performance pay. Both groups also received the same feedback as to the results of the urinalysis testing. The two groups differed only in that participants in the abstinence-and-work group were required to provide urine samples that indicated recent cocaine abstinence (i.e., decreased urinary benzoylecgonine concentration of ≥20% per day from the last sample provided or benzoylecgonine concentration ≤300 ng/ml; adapted from procedures developed by Preston, Silverman, Schuster, & Cone, 1977) to gain access to the workplace and to maintain the maximum base pay of $8.00 per hour. If the participant provided a urine sample that did not meet the criteria for recent cocaine abstinence or if the participant failed to provide a scheduled sample, the participant was not allowed to work that day and his or her base pay was decreased to $1.00 per hour. In addition, the participant was required to provide a urine sample every workday until he or she provided a sample that met the abstinence requirement. After a participant's base pay was reset, it increased by $1.00 per hour to a maximum of $8.00 per hour for every day that the participant met the cocaine abstinence requirement and worked at least 5 min. The voucher system and the schedule of escalating reinforcement for sustained abstinence and workplace attendance were adapted from a system developed by Higgins et al. (1991).

General Workplace Procedure

The therapeutic workplace operated according to a standard set of procedures that applied to all participants.

Hours of Operation

The therapeutic workplace workrooms were open for formal training from 10:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m. and 1:00 p.m. to 3:00 p.m. every weekday, except for holidays and weather emergencies.

Workplace Sign-in

Participants reported to the workplace sign-in station when they arrived at work each day. When the participant reported to the sign-in station, the sign-in station assistant signed the participant into the workplace by swiping the participant's bar-coded picture identification (ID) card through the electronic card reader. The Web-based therapeutic workplace application program recorded each participant's arrival time.

Urine Collection, Testing, and Feedback

After signing into the workplace on mandatory urine days (typically Monday, Wednesday, and Friday of each week), participants were required to provide urine and breath samples under observation by a same-gender research staff member. Urine collection was performed using well-developed and elaborate urine-collection procedures designed to ensure the collection of valid urine samples. Immediately after the sample was provided, the staff member tested the urine temperature. A urine sample was accepted only if the temperature was within a maximum (37.2° C) and minimum (33.3° C for women; 34.4° C for men) temperature range. If a participant provided a sample outside the required temperature, he or she was required to provide a new sample. Urine samples were tested for cocaine and opiates. Testing for cocaine was performed to determine the concentration of the cocaine metabolite (benzoylecgonine) in the sample using serial dilution procedures as needed (adapted from Preston et al., 1997). Opiate samples were tested only to determine if the concentration of the heroin metabolite (morphine) in the sample exceeded the standard cutoff (300 ng/ml).

For participants who had to provide evidence of recent cocaine abstinence to enter the workroom, immediately after the participant provided the urine sample, the sample was tested and the results (i.e., the quantitative value in nanograms per milliliter for benzoylecgonine and the dichotomous result of negative or positive for opiates) were entered into the therapeutic workplace software. The software automatically determined whether or not the sample met the cocaine abstinence criterion for that day, displayed a message reporting the result of that determination, and printed a feedback graph to be given to the participant. The feedback graph showed on a log scale the benzoylecgonine concentrations of all samples provided by the participant over consecutive calendar days, along with a line indicating the criterion for cocaine abstinence for each of the days. In addition, a text box was printed to the side of the graph that indicated the results for the current day including the benzoylecgonine concentration, whether the sample tested negative or positive for opiates, and if the participant was granted access to the workplace. If the sample met the cocaine abstinence requirement, the sign-in station assistant gave the participant his or her bar-coded ID card to bring to the workroom assistant to gain entrance to the workroom.

During conditions in which there were no contingencies on cocaine abstinence to gain access to the workplace (i.e., during baseline and during the intervention period for the work-only participants), immediately after a participant provided a urine sample and before the sample was tested, the sign-in station assistant handed the participant his or her ID card to bring to the workroom assistant to gain entrance to the workroom. Later that day, the participant's sample was tested, the results were entered into the therapeutic workplace software, and a feedback graph (identical to the one described above) was printed and delivered to the participant.

General Workroom Procedure

When the sign-in station assistant handed the participant his or her ID card, the participant brought the ID to a workroom assistant stationed at the entrance to the workrooms. The workroom assistant then swiped the ID card through the barcode reader at the entrance, which signed the participant into the workroom. The participant was then allowed to enter the workroom. If the participant ever left the workroom for a break, the workroom assistant swiped the participant's ID card through the barcode reader again, which signed the participant out of the workroom. The therapeutic workplace software recorded all of the times that the participant entered and left the workroom, and determined from those times the number of hours that each participant spent in the workroom each day.

Each participant was assigned a personal workstation. Throughout each workday, participants sat at their workstations to work on the computerized typing, keypad, and data-entry training programs. Participants worked on the typing program in the morning (10:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m.) and the keypad program in the afternoon (1:00 p.m. to 3:00 p.m.). When a participant completed one of those programs, the participant stopped working on that program and started working on the data-entry training program.

Typing, Keypad, and Data-entry Training Programs

The typing and keypad programs were designed to teach participants to copy characters using the alphanumeric keyboard and the number pad, respectively. The programs assumed no typing or keypad skills. Both programs were divided into small steps that participants could master sequentially. The steps gradually increased in complexity and difficulty by teaching progressively more characters across steps, requiring progressively faster typing speeds, and allowing progressively fewer errors to master a step. Participants earned $0.03 in vouchers for every 20 correct responses, lost $0.01 for every two incorrect responses (except for the first three steps), and earned bonuses for mastering steps that started at $0.25 and $0.63 for the typing and keypad programs and increased to $1.25 and $1.63, respectively.

In both of the programs, participants practiced the skills being taught on a step in short timings that lasted 1 min each. Prior to starting a timing, the screen displayed the participant's current step number, the possible earnings and losses for correct and incorrect responses and for mastering the step, and the minimum number of correct responses required and the maximum number of incorrect responses allowed to master the step. Within each timing, participants were repeatedly presented with sample lines of text to copy until the timing ended. Directly below each line of text was a participant entry line in which typed keys were displayed. After a participant completed a timing, a feedback screen displayed a message that indicated the number of correct and incorrect characters typed and the amount earned on that timing.

The mastery criteria for steps were specified in terms of a required number of correct characters per minute and maximum number of incorrect characters per minute. Once a participant met the mastery criteria for a given step, the program automatically moved the participant to the next step. To ensure that participants did not look at the keys, keyboards always had opaque plastic keyboard covers. In addition, participants were periodically provided with finger placement training and had to pass periodic staff-administered technique reviews to ensure that they were using the proper typing technique.

The data-entry training program was designed to teach participants how to enter data from a paper copy into the computerized data-entry program. The data-entry training program was structured much like the typing and keypad training. The program consisted of steps that participants must master sequentially. Participants were required to meet mastery criteria for each step before progressing to the next. In this program, participants were given paper batches of data that they were required to enter into the data-entry program. Batches consisted of multiple forms of data (surveys, questionnaires, etc.). Each form was one complete survey or questionnaire. A specified number of forms made up one batch. The data-entry training program printed batches from known files of data. Each batch and each form had a unique identifier. To begin entering a batch of data, the participant had to enter the unique identifier for that batch. Each form also had a printed form ID, which the participant entered to identify that form. Once the batch and each form were identified to the system in this way, the system could immediately evaluate the accuracy of the entered data. When the participant entered all of the forms in a batch, he or she pressed a button that caused the software to grade the entered batch. When graded, the system recorded the number of correct and incorrect responses in the batch and the total time required for the participant to complete the batch. From those data, the system calculated the percentage correct and the number of responses entered per hour. After the batch was graded, a screen displayed the percentage correct, the characters per hour, and the earnings for that batch.

Each step included multiple batches of similar size (i.e., the number of forms and characters) and complexity (i.e., the variety of characters). The size and the complexity increased across steps. A participant continued working on batches on a particular step until he or she met the mastery criteria for that step. To meet the mastery criteria for a step, the participant had to achieve a required percentage of correct characters and number of responses per hour. To promote endurance, the number of batches for which the participant had to sustain the mastery criteria also increased across steps.

Training performances were reviewed routinely. If a participant had difficulty mastering a particular step, remedial steps were inserted in the particular training program to try to rectify the problem.

Voucher System

On each participant's home page, the therapeutic workplace software system continuously displayed and updated an electronic voucher that showed data for the current day including the hourly pay rate, hours worked, paid hours (hours worked plus paid break minutes), base pay earnings, accuracy and earnings on each of the training programs, and summary information including the voucher account balance.

The voucher system was adapted from a system developed by Higgins et al. (1991) for the treatment of primary cocaine-dependent patients. Participants could use voucher earnings to purchase goods and services available in the community. When a participant accumulated enough voucher earnings, he or she could complete a purchase order to request a specific item. The staff member then purchased the item in the community. Gift certificates and gift cards were kept on hand from popular vendors to reduce the costs associated with making individual purchases and to expedite the purchasing process. For all purchases except those involving gift certificates, purchase orders submitted by 5:00 p.m. on Monday and Wednesday were available to be picked up on Wednesday and Friday, respectively. Purchase orders requesting gift certificates that the program had in stock could be placed and picked up the same day. Finally, participants who worked at least 1 hr could receive a $4 voucher to purchase food at the cafeteria on the hospital campus. All participants also received weekly bus passes.

On days that the therapeutic workplace was closed due to holidays or severe weather emergencies, participants could receive closing pay equal to the average amount earned on the days immediately preceding and following the closing. Participants did not receive closing pay if their base pay was reset for any reason on the day either before or after the closing.

Trainee Instructions

At the beginning of each study period (the baseline and intervention periods), each participant was given a detailed trainee instruction manual describing the therapeutic workplace rules and procedures, including the rules according to which the participant could earn vouchers. Multiple-choice questions were interspersed throughout each trainee manual to ensure that participants learned the most critical information. The workroom assistant read the instructions and questions to the participant as the participant followed along and answered the questions on his or her copy. After the participant selected his or her answers to a group of questions on a particular paragraph, the workroom assistant scored the answers, explained any errors, and asked the participant to correct any incorrect answers. After the participant completed the entire manual, using a new blank manual he or she was asked to answer all of the questions that were answered incorrectly the first time through the manual. Participants could earn $0.20 for every question answered correctly the first time and $0.10 for every question answered correctly the second time through. To ensure that participants continued to understand and remember the main voucher contingencies, follow-up review quizzes were administered that included questions about the possible amounts of voucher earnings available and the contingencies for earning vouchers, as well as questions to ensure that participants could read and understand the electronic voucher displayed on the home page. Each participant kept a copy of the trainee manual at his or her workstation.

The instructions provided when a participant first enrolled in the program (baseline) were extensive (55 pages and 65 multiple-choice questions) and included information about all general aspects of the program. Three voucher reviews (25 questions each) were administered over the first few days following introduction to the program in baseline. When the participant enrolled in the intervention, additional instructions were provided to describe the features that were unique to the participant's study condition (work only or abstinence and work). Those instructions focused on the duration of the condition, the maximum possible pay, whether or not cocaine abstinence was required to gain access to the workplace, and the details of the abstinence reinforcement contingency for participants in the abstinence-and-work group. A follow-up review quiz was also scheduled in the first days of this intervention.

Major and 30-day Assessments

Major assessments were conducted prior to random assignment, at the end of the 6-month intervention, and 6 months later (follow-up). Thirty-day assessments were conducted every 30 days throughout the intervention. The interviewers were not told about the group assignment of participants, although complete blinding of group assignment could not be assured because of the nature of the conditions. Adverse event questionnaires were also completed if a staff member learned of an adverse event at any time while a participant was enrolled in the study. No adverse events were considered to be related to the study interventions.

Major assessments included urine and breath collection and testing, the ASI Lite (without psychiatric section), the VEA, the RAB, and the TSR. Except at the 6-month follow-up, a modified Therapeutic Workplace Satisfaction Questionnaire (Silverman et al., 1996) and a computerized delayed discounting assessment (Johnson & Bickel, 2002) were also administered.

Thirty-day assessments included collection and testing of a urine (tested for opiates, cocaine and methadone) and breath sample, the ASI Lite (without psychiatric section), and the Therapeutic Workplace Satisfaction Questionnaire.

Standard Treatment Services

Participants were enrolled in a methadone treatment program and therefore were receiving routine drug abuse counseling during their study participation. Participants in the work-only and abstinence-and-work groups reported receiving statistically similar average maximum methadone doses of 108 mg (SEM 5.8) and 112 mg (SEM 6.6), and only 3% and 6% of their urine samples provided at 30-day assessments during the intervention period were negative for methadone. They were offered referrals to community services throughout the study and to employment services 6 weeks prior to their discharge date.

Data Analysis

The two groups were compared on measures collected at intake using Fisher's exact tests for dichotomous variables. Due to the relatively small sample size, both t tests and Mann-Whitney U were used to compare the two groups on continuous intake variables. The two groups differed significantly on four variables (Table 1). For analyses of outcome variables, two of these variables were used as covariates because they were significant in both the parametric and nonparametric analyses. All analyses were conducted without and with these intake variables included as covariates. Additional covariates could not be justified because of the small sample sizes.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Participants

| Variable | Work only | Abstinence and work | Fisher's exact |

t test/Mann-Whitney |

| p | p | |||

| Age, M (SD), yearsa | 47.5 (5.8) | 43.9 (6.5) | .03/.06 | |

| Black/white/other, %a | 89.3/7.1/3.6 | 92.9/7.1/0 | .60 | |

| Married, %a | 21.4 | 21.4 | 1.0 | |

| HIV positive, %a | 25.0 | 21.4 | .56 | |

| High school diploma or GED, %a | 53.6 | 53.6 | 1.0 | |

| Attended training past 30 days, %b | 0.0 | 3.6 | 1.0 | |

| Usually unemployed past 3 years, %a | 42.9 | 60.7 | .29 | |

| Past 30 days income, M (SD), $a | ||||

| Employment | 13 (33) | 24 (53) | .33/.45 | |

| Unemployment | 0 (0) | 22 (116) | .33/.32 | |

| Welfare | 105 (133) | 80 (135) | .49/.32 | |

| Pension, benefits, or Social Security | 217 (276) | 68 (181) | .02/.03 | |

| Mate, family, friends | 53 (71) | 90 (142) | .22/.39 | |

| Illegal | 82 (234) | 6 (21) | .10/.13 | |

| Living in poverty %c | 100 | 100 | ||

| Days used, past 30 days, M (SD), no.a | ||||

| Cocaine | 16.1 (11.0) | 22.3 (9.2) | .03/.03 | |

| Heroin | 8.5 (9.7) | 9.5 (10.4) | .71/.84 | |

| $ on drugs, past 30 days, M (SD)a | 346 (448) | 322 (412) | .84/.70 | |

| Drug abuse treatments, M (SD), no.a | 6.5 (4.6) | 5.3 (3.4) | .28/.42 | |

| Illegal activity for $, past 30 days, %a | 25.0 | 10.7 | .30 | |

| Currently on parole or probation, %a | 14.3 | 17.9 | 1.0 | |

| Felony conviction in life, %a | 82.1 | 71.4 | .53 | |

| ASI composite score, M (SD)a | ||||

| Medical | 0.25 (0.27) | 0.28 (0.33) | .71/.81 | |

| Employment | 0.90 (0.17) | 0.90 (0.14) | .98/.91 | |

| Alcohol | 0.16 (0.19) | 0.21 (0.31) | .51/.62 | |

| Drug | 0.35 (0.11) | 0.39 (0.13) | .26/.31 | |

| Legal | 0.16 (0.21) | 0.07 (0.18) | .09/.04 | |

| Psychiatric | 0.17 (0.18) | 0.15 (0.20) | .81/.58 | |

| Cocaine dependence, %d | 89.3 | 92.9 | 1.0 | |

| Alcohol dependence, %d | 28.6 | 28.6 | 1.0 | |

| Distance to TW, M (SD), miles | ||||

| From home | 6.8 (3.6) | 7.1 (3.4) | .72/.53 | |

| From methadone program | 6.6 (1.5) | 6.6 (2.1) | .89/.42 | |

Note. BZE = benzoylecgonine, TW = therapeutic workplace.

From the Addiction Severity Index Lite (ASI Lite).

From the Treatment Services Review (TSR).

Based on U.S. Census Bureau Poverty Thresholds 2003. Weighted average thresholds for one person under 65 years = $9,573 and 65 years and over = $8,825. Annual income per participant was calculated by taking the sum of the employment, unemployment, welfare, and pension, benefits, or Social Security income from the past 30 days and multiplying by 12.

From the DSM checklist.

Dichotomous outcome measures (e.g., cocaine positive or negative) assessed at single time points (i.e., baseline, intake, and 6-month follow-up) were analyzed with logistic regression. Dichotomous outcome measures assessed repeatedly over time were analyzed using general estimating equations (GEE; Zeger, Liang, & Albert, 1988). Results for both logistic regression and GEE are reported as odds ratios (OR), indicating the likelihood that the abstinence-and-work group had different outcomes than the work-only group, and 95% confidence intervals (CI) surrounding the OR. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.1 for Windows. All analyses included intent-to-treat samples (i.e., all participants who were originally randomly assigned to the work-only and abstinence-and-work groups), were two-tailed, and were considered significant at p ≤ .05.

For all figures, tables, and analyses, urine samples were considered negative for cocaine or opiates if the urinary metabolite (benzoylecgonine or morphine, respectively) concentration was ≤300 ng/ml. To address the problem of missing data, three analyses were conducted that differed in the way the missing urine samples were treated. For the “missing positive” analyses, missing samples were considered positive. For the “missing = missing” analyses, missing samples were not replaced. For the “missing interpolated” analyses, samples were considered negative only if the samples provided before and after the missing sample (or group of samples) were negative.

Cocaine urinalysis (positive or negative) results of mandatory urine samples and 30-day assessment urine samples collected repeatedly throughout the 26-week intervention were the primary outcome measures. The adjusted (for reported days of cocaine use and pension, benefits, and social security income) analyses, using the missing positive method of replacing missing urine samples, were considered the primary analyses. Counting missing urine samples as positive is generally considered the most conservative approach to handling missing samples and has been used commonly in prior similar studies (Higgins et al., 1994, 2000; Rawson et al., 2002; Silverman et al., 1996). It was a particularly conservative approach in this study, because abstinence-and-work participants were expected to and did have more missing mandatory urine samples than the work-only group. All measures of opiate use and all self-report measures were considered secondary.

Results

Participant Characteristics and Flow-through Study

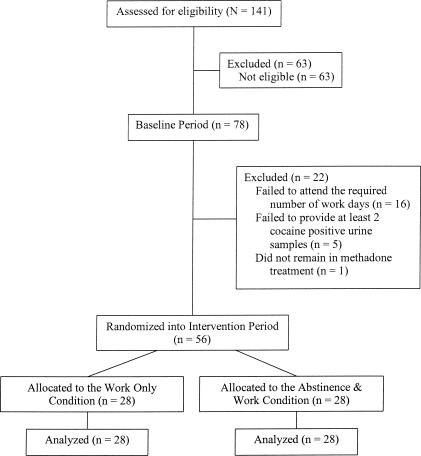

Table 1 shows that the two study groups were similar on most measures assessed at intake. The groups differed significantly on four of the measures, but those differences were significant on both the parametric and nonparametric tests for only two of the measures (reported days of cocaine use and pension, benefits, and social security). Those two measures were used as covariates in the remaining analyses. Figure 1 shows the progress of participants through the study.

Figure 1.

The flow of participants through the study.

Drug Abstinence

Monday, Wednesday, and Friday Urinalysis

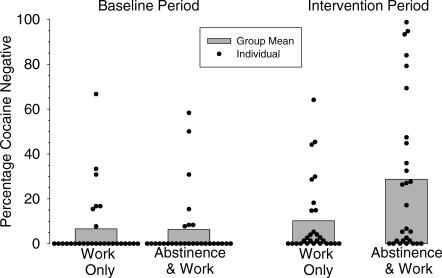

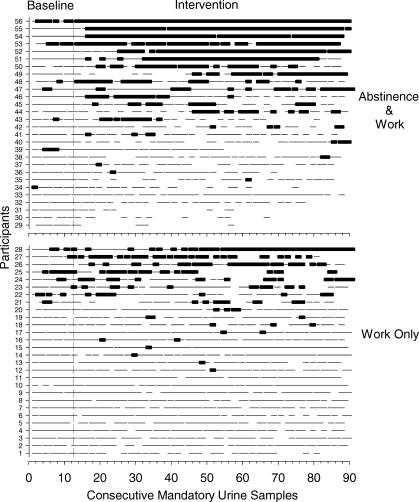

Using GEE with two covariates (reported days of cocaine use and pension, benefits, and social security), the two treatment groups were compared on dichotomous measures of drug abstinence at the baseline and intervention phases of the study. Analyses based on urine samples collected every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday showed that abstinence-and-work and work-only participants provided very low rates of cocaine-negative mandatory urine samples during baseline (6.3% and 6.6% of all measured samples, respectively; Figures 2 and 3 and Table 2). During intervention, the abstinence-and-work group provided significantly higher rates of cocaine-negative mandatory samples than the work-only group (29% and 10%, respectively; adjusted OR 5.80, CI 2.03–16.56).

Figure 2.

Percentage of urine samples negative for cocaine during baseline (left) and intervention (right) for work-only and abstinence-and-work groups. Points represent data for individual participants for each period, and the bars represent group means. Data are based on mandatory urine samples collected on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday of each week. All missing samples were considered positive.

Figure 3.

Cocaine urinalysis results across consecutive urine samples for individual participants in each of the two experimental conditions. The vertical dashed lines divide each panel into two periods, baseline (left) and intervention (right). Within each panel, horizontal lines represent the cocaine urinalysis results for individual participants across the consecutive scheduled mandatory urine-collection days. The heavy portion of each line represents cocaine-negative urinalysis results, the thin portion of each line represents cocaine-positive urinalysis results, and the blank portions represent missing urine samples. Within each panel, participants are arranged from those showing the least abstinence (fewest cocaine-negative urines) on the bottom to those with the most abstinence on the top.

Table 2.

Comparisons of Treatment Groups for Dichotomous Measures of Drug Abstinence and HIV Risk Behaviors Assessed at the Major and 30-Day Assessments Using Logistic Regression and GEE

| Overall percentage |

Adjusted analysesa |

|||

| Work only | Abstinence and work | |||

| p | OR (95% CI) | |||

| Cocaine-negative urinalysis | ||||

| Intake | 0 | 0 | — | — |

| Baseline | 3.6 | 10.7 | .14 | 3.71 (0.77–17.86) |

| Intervention | 14.3 | 27.4 | .01 | 5.02 (1.53–16.49) |

| 6-month follow-up | 35.7 | 21.4 | .64 | 0.73 (0.20–2.68) |

| Opiate-negative urinalysis | ||||

| Intake | 57.1 | 60.7 | .73 | 1.23 (0.39–3.90) |

| Baseline | 78.6 | 42.9 | .02* | 0.22 (0.06–0.79) |

| Intervention | 62.5 | 55.4 | .82 | 0.91 (0.40–2.08) |

| 6-month follow-up | 60.7 | 50.0 | .98 | 0.98 (0.28–3.38) |

| Reported cocaine abstinenceb | ||||

| Intake | 0 | 0 | — | — |

| Baseline | 0 | 0 | — | — |

| Intervention | 11.9 | 22.6 | .03 | 4.60 (1.35–15.67) |

| 6-month follow-up | 28.6 | 25.0 | .64 | 1.34 (0.39–4.60) |

| Reported opiate abstinenceb | ||||

| Intake | 14.3 | 14.3 | .89 | 1.12 (0.21–5.89) |

| Baseline | 28.6 | 57.1 | .01* | 4.72 (1.35–16.55) |

| Intervention | 48.8 | 50.6 | .64 | 1.23 (0.52–2.92) |

| 6-month follow-up | 53.6 | 53.6 | .86 | 1.11 (0.35–3.51) |

| Reported no injection drug useb | ||||

| Intake | 0 | 0 | — | — |

| Baseline | 32.1 | 32.1 | .59 | 0.72 (0.22–2.34) |

| Intervention | 48.2 | 61.3 | .32 | 1.65 (0.62–4.44) |

| 6-month follow-up | 60.7 | 57.1 | .65 | 0.76 (0.23–2.53) |

| Reported no crack useb | ||||

| Intake | 89.3 | 82.1 | .47 | 0.57 (0.12–2.79) |

| Baseline | 64.3 | 75.0 | .16 | 2.46 (0.70–8.67) |

| Intervention | 56.0 | 55.4 | .51 | 1.36 (0.55–3.36) |

| 6-month follow-up | 60.7 | 46.4 | .52 | 0.68 (0.21–2.18) |

| Reported no injection drug or crack useb | ||||

| Intake | 0 | 0 | — | — |

| Baseline | 3.6 | 10.7 | .18 | 3.30 (0.62–17.63) |

| Intervention | 16.1 | 28.0 | .04 | 3.37 (1.21–9.37) |

| 6-month follow-up | 28.6 | 28.6 | .49 | 1.53 (0.46–5.14) |

| Assessment collected | ||||

| Intake | 100 | 100 | — | — |

| Baseline | 100 | 100 | — | — |

| Intervention | 98.2 | 95.2 | .19 | 2.47 (0.62–9.73) |

| 6-month follow-up | 100 | 96.4 | — | — |

Note. Data for the intake, baseline and 6-month follow-up assessments were each based on single measures per subject resulting in 28 measures per group and were analyzed with logistic regression; data for the intervention period were based on 168 measures per group (one measure at each of the six 30-day assessments for each of the 28 participants) and were analyzed with GEE. Dashes indicate that values could not be computed due to insufficient variability in the data. CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

Adjusted for days of cocaine use and pension, benefits, and Social Security income reported at intake.

In the last 30 days as assessed in the Addiction Severity Index.

* Statistically significant (p ≤ .05) difference between groups in unadjusted analysis.

Urinalysis and Self-report of Drug Use on Major and 30-day Assessments

Adjusted logistic regression analyses for the assessment conducted immediately prior to random assignment (i.e., baseline) showed a significant difference between groups on the percentage of urine samples that were negative for opiates and reports of opiate abstinence in baseline (Table 3). However, the more complete analysis of baseline opiate use based on urine samples collected every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday across the 4 weeks of baseline (Table 2) showed that the abstinence-and-work and work-only groups had virtually identical rates of opiate-negative samples (59% and 53%, respectively).

Table 3.

Comparisons of Treatment Groups for Dichotomous Measures of HIV Risk Behaviors Assessed at the Major Assessments Using Logistic Regression

| Overall percentage |

Adjusted analysesa |

|||

| Work only | Abstinence and work | |||

| p | OR (95% CI) | |||

| Shared needles or works | ||||

| Intake | 28.6 | 50.0 | .45 | 0.60 (0.16–2.22) |

| Baseline | 39.3 | 28.6 | .37 | 1.73 (0.52–5.77) |

| Intervention | 17.9 | 21.4 | .99 | 1.01 (0.25–4.07) |

| 6-month follow-up | 17.9 | 28.6 | .34 | 0.51 (0.13–2.08) |

| Been to shooting gallery | ||||

| Intake | 28.6 | 42.9 | .56 | 0.71 (0.23–2.25) |

| Baseline | 17.9 | 25.0 | .68 | 0.76 (0.20–2.84) |

| Intervention | 0.0 | 14.3 | — | — |

| 6-month follow-up | 3.6 | 17.9 | .08 | 0.12 (0.01–1.35) |

| Been to crack house | ||||

| Intake | 17.9 | 39.3 | .23 | 0.47 (0.13–1.64) |

| Baseline | 14.3 | 25.0 | .08 | 0.29 (0.08–1.07) |

| Intervention | 3.6 | 17.9 | .21 | 0.23 (0.02–2.32) |

| 6-month follow-up | 17.9 | 17.9 | .76 | 0.77 (0.14–4.23) |

| Traded sex for drugs or money | ||||

| Intake | 21.4 | 21.4 | .71 | 1.31 (0.33–5.27) |

| Baseline | 14.3 | 7.1 | .25 | 3.02 (0.48–18.85) |

| Intervention | 7.1 | 3.6 | — | — |

| 6-month follow-up | 7.1 | 17.9 | .26 | 0.32 (0.04–2.45) |

Note. Data for the intake, baseline, intervention, and 6-month follow-up assessments were each based on 28 measures per group. Dashes indicate that values could not be computed due to insufficient variability in the data. CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

Adjusted for days of cocaine use and pension, benefits, and Social Security income reported at intake to the study.

Adjusted GEE analyses of data collected at the 30-day assessments throughout the intervention (Table 3) showed that significantly more participants in the abstinence-and-work group provided cocaine-negative urine samples, reported remaining abstinent from cocaine, and reported staying completely abstinent from both crack and injection drug use.

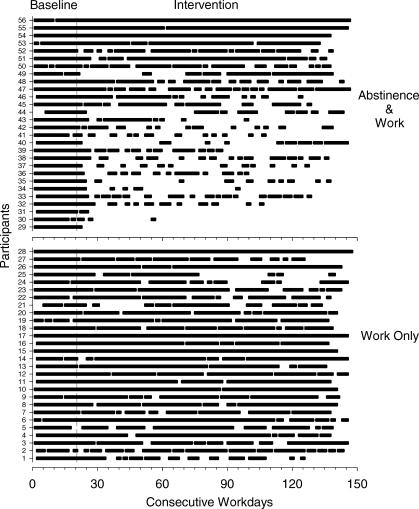

Attendance Outcomes

Abstinence-and-work and work-only participants attended the workplace at high rates during baseline (85% and 82% of days, respectively; Figure 4 and Table 2). Work-only participants continued high rates of attendance throughout the intervention. Attendance by abstinence-and-work participants decreased during the intervention when the cocaine urinalysis contingency was arranged, although most participants continued to attend at least intermittently throughout the intervention (Figure 4). During the intervention, work-only participants attended the workplace at significantly higher rates than did abstinence-and-work participants (71% and 39% of days, respectively; adjusted OR 3.77, CI 2.25–6.33; Table 2).

Figure 4.

Attendance of all participants in the workplace across consecutive workdays of baseline and intervention. Each horizontal line represents data for a different participant. The solid portion of each line represent days that a participant attended the workplace (i.e., spent at least 5 min in the workroom); open portions represent days that the participant did not attend. Within each panel, participants are displayed in the same order that they appear in Figure 3.

Self-reports of Hiv Risk Behaviors

There were no group differences on measures of HIV risk behaviors as assessed by the RAB (Table 4), although the proportion of participants who engaged in HIV risk behaviors tended to decrease over time, particularly during intervention.

Table 4.

Comparison of Treatment Groups for Dichotomous Measures of Drug Abstinence and Attendance During Workplace Participation Using GEE

| Overall percentage |

Adjusted analysesa |

|||

| Work only | Abstinence and work | |||

| p | OR (95% CI) | |||

| Cocaine-negative urinalysis | ||||

| Baseline | ||||

| Missing positiveb | 6.6 | 6.3 | .64 | 1.30 (0.44–3.83) |

| Missing missingc | 7.9 | 7.3 | .71 | 1.24 (0.41–3.78) |

| Missing interpolatedb | 7.2 | 6.6 | .71 | 1.24 (0.41–3.78) |

| Intervention | ||||

| Missing positived | 10.2 | 28.7 | .004* | 5.80 (2.03–16.56) |

| Missing missinge | 14.0 | 47.5 | .001* | 6.08 (2.27–16.32) |

| Missing interpolatedd | 14.9 | 29.9 | .006 | 4.81 (1.75–13.22) |

| Opiate-negative urinalysis | ||||

| Baseline | ||||

| Missing positiveb | 53.0 | 59.3 | .35 | 1.43 (0.68–3.02) |

| Missing missingc | 63.4 | 68.8 | .44 | 1.39 (0.60–3.20) |

| Missing interpolatedb | 58.5 | 65.0 | .39 | 1.45 (0.63–3.33) |

| Intervention | ||||

| Missing positived | 47.8 | 42.5 | .75 | 0.89 (0.45–1.78) |

| Missing missinge | 65.6 | 70.2 | .90 | 0.95 (0.42–2.16) |

| Missing interpolatedd | 62.3 | 56.7 | .85 | 0.92 (0.40–2.12) |

| Days in attendance | ||||

| Baselinef | 82.1 | 85.5 | .12 | 0.71 (0.47–1.08) |

| Interventiong | 71.3 | 38.6 | <.001* | 3.77 (2.25–6.33) |

| Collected urine samples | ||||

| Baselineb | 83.7 | 86.2 | .37 | 0.78 (0.46–1.33) |

| Interventiond | 72.9 | 60.4 | .06* | 1.67 (1.02–2.75) |

Note. Measures of drug abstinence based on mandatory Monday, Wednesday, and Friday urine samples provided when attending the workplace. Measures of attendance based on all weekdays that the workplace was open during the study. CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

Adjusted for days of cocaine use and pension, benefits, and Social Security income reported at intake.

Based on 349 samples for both work only and abstinence and work.

Based on 292 samples for work only and 301 samples for abstinence and work.

Based on 2,121 samples for work only and 2,123 samples for abstinence and work.

Based on 1,546 samples for work only and 1,283 samples for abstinence and work.

Based on 571 days for both work only and abstinence and work.

Based on 3,347 days for work only and 3,357 days for abstinence and work.

Statistically significant (p ≤ .05) differences between groups in unadjusted analysis.

Self-reports of Therapeutic Workplace Satisfaction

Overall, ratings on the Therapeutic Workplace Satisfaction Questionnaire showed that participants generally gave favorable ratings to the treatment. When asked “Compared to other drug abuse treatments you have received in the past, how would you rate the treatment you are receiving at the therapeutic workplace?” on a 5-point scale (0 = much worse, 1 = worse, 2 = same, 3 = better, 4 = much better), the majority of ratings in the two groups (96% and 94% of all ratings, respectively) were 3 or 4. The average ratings in the two groups were not significantly different from each other during baseline or intervention.

Progress on Training Programs

On average, work-only and abstinence-and-work participants progressed to Steps 31.3 (SE = 3.3) and 29.4 (SE = 3.4) on the typing training program, Steps 15.4 (SE = 1.0) and 14.5 (SE = 1.0) on the keypad training program, and Steps 7.8 (SE = 1.9) and 3.4 (SE = 1.3) on the data-entry training program, respectively. There were no significant differences between the two groups on these measures based on t tests.

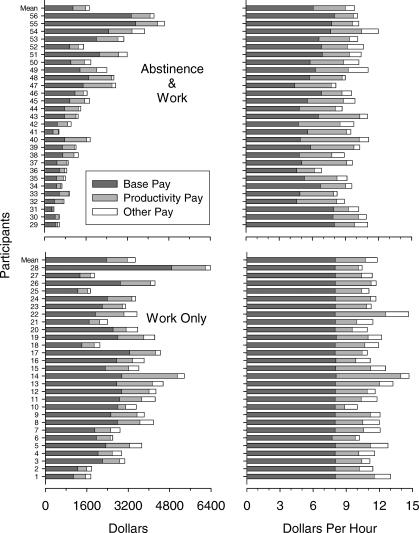

Voucher Earnings

Participants in the work-only and abstinence-and-work groups earned a mean of $3,477 and $1,732 in total pay, respectively (Figure 5). Overall, participants in the work-only and abstinence-and-work groups earned a mean $12.00 and $10.00 per hour, respectively, based on all of the time they worked (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Dollars (left) and dollars per hour (right) earned in vouchers for all participants in the workplace across baseline and intervention. Each horizontal bar represents data for a different participant. The dark gray portion of the bars represents base pay earnings, the light gray portion of the bars represents productivity pay earnings for performance on training programs, and the open portion of the bars represents other earnings (i.e., administrative pay for holidays and pay for answering questions on voucher instructions). Within each panel, participants are displayed in the same order that they appear in Figures 2 and 4. Participants with a mean of less than $8.00 per hour in base pay had one or more resets in base pay for positive or missing mandatory urine samples or serious professional demeanor violations.

Discussion

This study provides firm experimental evidence that employment-based abstinence reinforcement can increase cocaine abstinence. All participants were offered paid employment in a model work setting. Participants who were randomly assigned to a condition in which daily access to the workplace was made contingent on providing urinalysis evidence of recent cocaine abstinence achieved significantly higher rates of cocaine abstinence than did those who were allowed to work independent of their urinalysis results. The study has important implications for four major public health domains: drug addiction treatment, employment programs for chronically unemployed and drug-addicted individuals, HIV risk prevention, and workplace practices.

As a drug addiction treatment, this study shows that employment-based abstinence reinforcement can be an effective intervention, even for extremely persistent drug users who fail to respond to conventional treatment approaches. The study was conducted in individuals who persisted in high rates of cocaine use despite participation in community methadone treatment. During the 4 weeks in the workplace prior to random assignment, about 6% of the urine samples provided by both groups were negative for cocaine (Table 2, Figures 2 and 3), and 75% of participants in both groups failed to provide even one cocaine-negative urine sample (Figure 3). Given that a high rate of cocaine use is a robust predictor of poor treatment outcome (Preston et al., 1998; Silverman et al., 1996, 1998), and given the limited number of treatments that have shown efficacy in treating cocaine abuse in methadone patients (Silverman et al., 1998), the demonstrated effects on cocaine use in this population are particularly noteworthy.

The study has direct implications for employment programs for chronically unemployed adults with long histories of drug addiction. A number of employment programs for chronically unemployed adults have provided intensive education, job-skills training, and supported work (Dickinson & Maynard, 1981; Drebing et al., 2005; Kashner et al., 2002; Magura et al., 2004; Milby et al., 1996); some of those programs have provided stipends for participation in training and supported work (Dickinson & Maynard; Drebing et al.; Kashner et al.; Milby et al.); one of the programs provided additional payments for abstinence and for meeting program objectives (Drebing et al.); and some programs have required participants to maintain abstinence from drugs to continue to work and earn wages (Kashner et al.; Milby et al.). One of the largest and most recognized of those programs is the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs' Compensated Work Therapy (CWT) program (Kashner et al.). A recent randomized study evaluated the program in homeless veterans with substance abuse problems and showed that compared to individuals who did not participate in the program, CWT participants experienced significant reductions in drug-related problems, homelessness, and incarcerations (Kashner et al.). The CWT program arranged contingencies for abstinence; however, the nature of the contingencies and the consequences for drug use were guided by clinical judgment and were not well defined. Furthermore, the study did not show direct effects of the intervention on objective measures of drug use, or isolate which features of the CWT intervention were critical in improving the drug-related outcomes. For the large numbers of drug-addicted and chronically unemployed individuals who participate in employment programs, the current study suggests that paid training and supported employment programs could be used to simultaneously train participants and promote drug abstinence if daily access to the training program were made contingent on verified abstinence. Further, the current study provides precise guidelines as to how those contingencies can be effectively arranged and provides clear evidence that arranging abstinence-contingent access to paid training can substantially increase abstinence rates above rates observed under conditions in which paid training and supported employment are offered without such contingencies.

The study suggests that employment-based abstinence reinforcement may be effective in reducing the spread of HIV infection. All participants in this study were injection drug users, over 20% reported being HIV positive (Table 1), and over 20% reported sharing injection equipment, going to shooting galleries or crack houses, and trading sex for drugs or money (Table 4). In this population, employment-based abstinence reinforcement increased urinalysis-verified cocaine abstinence (Tables 2 and 3 and Figures 2 and 3) as well as the proportion of participants who self-reported abstaining from injection drug and crack use (Table 3), behaviors that have been associated with increases in risk of HIV infection. The study did not show significant effects on other HIV risk behaviors (e.g., trading sex for money or drugs), possibly due to the relatively small sample size.

The study provides a model for drug-addiction treatment in the workplace. Through the growth of employee assistance programs, the workplace has increasingly become recognized as an important context in which to detect and treat drug addiction (Hartwell et al., 1996; Office of Applied Studies, 2002). It is important to note that urinalysis-testing programs, including random testing, are already used in many workplaces (French, Roebuck, & Kebreau Alexandre, 2004). Although those programs are mainly used as employment screening tools to eliminate people who abuse drugs from workplaces, this study suggests that parameters of those testing programs could be altered to achieve therapeutic benefits for drug-addicted employees. The integration of employment-based abstinence reinforcement contingencies into community workplaces will not be simple, and systematic research will be needed to determine how such integration might be accomplished. The current study suggests that employees who have persistent substance-abuse problems could be offered to participate in an employment-based abstinence reinforcement program as an alternative to termination or another option that might be less desirable to the employee. Under such a program, the employee could be required to provide urine samples under observation on a routine basis. If the employee provides a positive urine sample or fails to provide a scheduled sample, the employee would not be allowed to work that day or any day thereafter until he or she provides a drug-negative urine sample. The employee would also experience a temporary decease in pay.

Imposing contingencies on abstinence in this study had the undesirable effect of reducing attendance in the workplace. Future research should investigate methods to minimize this undesirable effect of the abstinence contingency. Nevertheless, almost all participants exposed to the abstinence requirement continued attending the workplace throughout the intervention period, at least intermittently (Figure 4); participants in the two groups achieved comparable skill levels on the training programs; and participants exposed to the abstinence contingencies still achieved approximately a three-fold increase in cocaine abstinence rates. Thus, the training objectives of the program were achieved for both groups while substantially increasing abstinence in the group exposed to the abstinence reinforcement contingencies.

One limitation of the study is that participants in the abstinence-and-work group provided fewer mandatory Monday, Wednesday, and Friday urine samples than did work-only participants (Figure 3 and Table 2), which makes comparison of the two groups more difficult. Different methods of replacing the missing data were used, and all methods generally showed similar outcomes.

Although the employment-based abstinence reinforcement contingency significantly increased rates of cocaine abstinence in this study, many participants did not initiate cocaine abstinence. This is not completely surprising, because they had extremely high baselines rates of cocaine use. As described above, individuals with the highest baseline rates of cocaine use have historically been the least likely to respond to abstinence reinforcement interventions (Preston et al., 1998; Silverman et al., 1996, 1998). Prior research has shown that abstinence can be promoted in treatment-resistant patients by manipulating reinforcement parameters such as magnitude (e.g., Silverman et al., 1999), and similar investigations will be required using employment-based abstinence reinforcement. The Web-based therapeutic workplace intervention should provide an efficient and highly controlled context to explore the utility of potential methods to improve treatment outcomes (Silverman, 2004).

Heroin use was not targeted in the abstinence reinforcement contingencies in this study, and many participants continued to use heroin. Prior research has shown abstinence from both heroin and cocaine can be achieved through abstinence reinforcement contingencies (Silverman et al., 2004). Future studies will need to develop procedures to produce abstinence from multiple drugs using employment-based abstinence reinforcement contingencies.

There were no differences in cocaine abstinence outcomes at the single-point follow-up assessment conducted 6 months after the end of treatment (Table 3). Cocaine abstinence in the abstinence-and-work group at follow-up appeared to be slightly lower than the cocaine abstinence levels observed during treatment; however, cocaine abstinence in the work-only group appeared to increase. Although we do not fully understand why we obtained this pattern of results, some observations and speculation might be useful. Careful review of the data shows that some of the data seem orderly and somewhat predictable, and some of the data are less easy to understand. As might be expected based on posttreatment outcomes from prior related research (Silverman et al., 1996, 2004), a few participants in the abstinence-and-work group who achieved substantial amounts of cocaine abstinence during treatment (S50, S55, and S56; Figure 3) appeared to be abstinent after treatment and provided a cocaine-negative sample at the 6-month follow-up (data not shown). Also consistent with prior research, several other abstinence-and-work participants who achieved abstinence during treatment (S47, S51, S52, S53, and S54; Figure 3) appeared to return to cocaine use and provided a cocaine-positive sample at the 6-month follow-up (data not shown). As might also be expected, many participants in the work-only control group who provided relatively frequent cocaine-negative samples during treatment (S23, S24, S25, S26, S27, and S28; Figure 3), presumably representing their usual patterns of cocaine use, also provided a cocaine-negative urine sample at the 6-month follow-up (data not shown). Somewhat less easy to understand is the fact that 3 work-only participants who never provided a single cocaine-negative sample throughout the 7 months of participation (S5, S9, and S11; Figure 3) provided a cocaine-negative urine sample at the 6-month follow-up (data not shown). This study was designed primarily to study the effects of the interventions on cocaine use during treatment, and therefore assessed patterns of cocaine use thoroughly during treatment through frequent and repeated urine collection and testing. It is possible that collection of a single urine sample 6 months after treatment did not fully or accurately capture the patterns of cocaine use and abstinence in the two groups after treatment ended. Alternatively, the 6-month follow-up results might accurately reflect the patterns of cocaine use in the two groups after treatment. If so, those results might reflect changes in life circumstances for some of the individuals (e.g., S5, S9, and S11) that we do not fully understand but that have little to do with the treatment assignments. Whatever the case, it will be important for future research to investigate posttreatment abstinence outcomes more fully, possibly by obtaining more frequent measures of cocaine abstinence during follow-up.

Overall, this study shows that employment-based abstinence reinforcement contingencies can be effective in promoting abstinence from cocaine in a population of treatment-resistant methadone patients who are at considerable risk for spreading or contracting HIV due to their continued high rates of injection and crack cocaine use and associated HIV risk behaviors. Use of employment-based abstinence reinforcement contingencies for this and other drug-addicted populations could be useful in addressing the critical and often intractable public health problem of drug addiction.

Acknowledgments

Conrad J. Wong and Paul Nuzzo are now at the Department of Behavioral Science, University of Kentucky College of Medicine, Lexington; Darlene Crone-Todd is now at the Department of Psychology, Delta State University, Cleveland.

This research was supported by Grants R01DA12564 and R01DA13107 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

We thank Carolyn Carpenedo and Haley Brown for staffing the workrooms, Kylene Broadwater for data and manuscript preparation, and Jacqueline Hampton for collection of assessments.

References

- Chaisson R.E, Bacchetti P, Osmond D, Brodie B, Sande M.A, Moss A.R. Cocaine use and HIV infection in intravenous drug users in San Francisco. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1989;261(4):561–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M, Bigelow G, Hargett A, Allen R, Halsted C. The use of contingency management procedures for the treatment of alcoholism in a work setting. Alcoholism. 1973;9:97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Crowley T.J. Doctor's drug abuse reduced during contingency-contracting treatment. Alcohol and Drug Research. 1986;6:299–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallery J, Silverman K, Chutuape M.A, Bigelow G.E, Stitzer M.L. Voucher-based reinforcement of opiate plus cocaine abstinence in treatment-resistant methadone patients: Effects of reinforcer magnitude. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2001;9(3):317–325. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.9.3.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson K, Maynard R. The impact of supported work on ex-addicts (No. 4) New York: Manpower Demonstration Research; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Donatelle R.J, Prows S.L, Champeau D, Hudson D. Randomized controlled trial using social support and financial incentives for high risk pregnant smokers: Significant other supporter (SOS) program. Tobacco Control. 2000;9:III67–III69. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.suppl_3.iii67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drebing C.E, Van Ormer E.A, Krebs C, Rosenheck R, Rounsaville B, Herz L, et al. The impact of enhanced incentives on vocational rehabilitation outcomes for dually diagnosed veterans. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2005;38:359–372. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2005.100-03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French M.T, Roebuck M.C, Kebreau Alexandre P. To test or not to test: Do workplace drug testing programs discourage employee drug use? Social Science Research. 2004;33&SetFont Italic="0";(1):45–63. doi: 10.1016/s0049-089x(03)00038-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwell T.D, Steele P, French M.T, Potter F.J, Rodman N.F, Zarkin G.A. Aiding troubled employees: The prevalence, cost, and characteristics of employee assistance programs in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86(6):804–808. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.6.804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins S.T, Badger G.J, Budney A.J. Initial abstinence and success in achieving longer term cocaine abstinence. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2000;8:377–386. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.8.3.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins S.T, Budney A.J, Bickel W.K, Foerg F.E, Donham R, Badger G.J. Incentives improve outcome in outpatient behavioral treatment of cocaine dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51(7):568–576. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950070060011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins S.T, Delaney D.D, Budney A.J, Bickel W.K, Hughes J.R, Foerg F, et al. A behavioral approach to achieving initial cocaine abstinence. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1991;148:1218–1224. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.9.1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins S.T, Heil S.H, Lussier J.P. Clinical implications of reinforcement as a determinant of substance use disorders. Annual Review of Psychology. 2004;55:431–461. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins S.T, Silverman K, editors. Motivating behavior change among illicit-drug abusers: Research on contingency management interventions. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins S.T, Wong C.J, Badger G.J, Ogden D.E, Dantona R.L. Contingent reinforcement increases cocaine abstinence during outpatient treatment and 1 year of follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68(1):64–72. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hser Y.I, Anglin M.D, Fletcher B. Comparative treatment effectiveness: Effects of program modality and client drug dependence history on drug use reduction. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1998;15(6):513–523. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(97)00308-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudziak J.J, Helzer J.E, Wetzel M.W, Kessel K.B, McGee B, Janca A, et al. The use of the DSM-III-R checklist for initial diagnostic assessments. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1993;34(6):375–383. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(93)90061-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M.W, Bickel W.K. Within-subject comparison of real and hypothetical money rewards in delay discounting. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2002;77:129–146. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2002.77-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashner T.M, Rosenheck R, Campinell A.B, Suris A, Crandall R, Garfield N.J, et al. Impact of work therapy on health status among homeless, substance-dependent veterans: A randomized controlled trial. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59(10):938–944. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lussier J.P, Heil S.H, Mongeon J.A, Badger G.J, Higgins S.T. A meta-analysis of voucher-based reinforcement therapy for substance use disorders. Addiction. 2006;101:192–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magura S, Staines G.L, Blankertz L, Madison E.M. The effectiveness of vocational services for substance users in treatment. Substance Use & Misuse. 2004;39(13–14):2165–2213. doi: 10.1081/ja-200034589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGovern M.P, Fox T.S, Xie H, Drake R.E. A survey of clinical practices and readiness to adopt evidence-based practices: Dissemination research in an addiction treatment system. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2004;26:305–312. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan A.T, Alterman A.I, Cacciola J, Metzger D, O'Brien C.P. A new measure of substance abuse treatment: Initial studies of the treatment services review. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1992;180(2):101–110. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199202000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan A.T, Carise D, Kleber H.D. Can the national addiction treatment infrastructure support the public's demand for quality care? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2003;25:117–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan A.T, Lewis D.C, O'Brien C.P, Kleber H.D. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: Implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284(13):1689–1695. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.13.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]