Abstract

Functional analyses were conducted to identify reinforcers for noncompliance exhibited by 3 young children. Next, the effects of three antecedent-based interventions—noncontingent access to a preferred item, a warning, and a high-probability instructional sequence—were examined. The high-probability instructional sequence was effective for 1 child. Antecedent interventions were ineffective and extinction was necessary for the other 2 children.

Keywords: extinction, functional analysis, high-probability sequence, noncompliance, preschool children, warnings

Noncompliance with instructions is common in preschool settings (Crowther, Bond, & Rolf, 1981) and may be particularly common when children are asked to terminate a preferred activity (e.g., free play) or initiate a nonpreferred activity (e.g., clean-up). Cote, Thompson, and McKerchar (2005) examined two common antecedent interventions to increase compliance by preschoolers. One intervention involved a warning delivered prior to a transition. The second involved providing the child with noncontingent access to a toy during a transition. Both interventions were ineffective when implemented alone, and extinction was necessary to increase compliance. However, no functional analysis was conducted as part of this study. Thus, although extinction was shown to be a necessary intervention component, it is not known if the target behaviors were maintained by positive or negative reinforcement. In addition, preference for the toys used during the second intervention was not formally assessed. The current study addressed these limitations by conducting functional analyses of noncompliance and stimulus preference assessments prior to intervention. In addition, a third antecedent intervention, the high-probability (high-p) instructional sequence (Rortvedt & Miltenberger, 1994) was evaluated.

Method

Participants and Setting

Eddie (a 30-month-old boy), Ricky (a 42-month-old boy), and Timmy (a 40-month-old boy) participated. Eddie and Ricky did not have a psychiatric diagnosis or a developmental disability, and Timmy had been diagnosed with Fragile X syndrome. All 3 participants had age-appropriate language skills and had been reported by a preschool teacher or nanny to ignore instructions. Sessions were conducted in a small room at the children's school (Ricky and Timmy) or home (Eddie). Two to six sessions were conducted per day, 2 to 3 days per week. A graduate research assistant, unfamiliar to the children, served as experimenter.

Response Measurement and Definitions

Data collectors recorded the occurrence or nonoccurrence of compliance (the child independently completing or initiating the activity described in the instruction within 10 s) on each instructional trial. A second independent observer recorded compliance during at least 50% of sessions for all children. Interobserver agreement was measured by comparing observers' records on a trial-by-trial basis. An agreement was defined as both observers recording an instance of either compliance or noncompliance on a given trial. Mean agreement was calculated by dividing the number of agreements by the number of agreements plus disagreements and multiplying by 100%. Agreement ranged from 94% to 100% for all participants during both the functional analysis and the intervention evaluation.

Data on integrity of the independent variable were collected by recording whether or not the therapist delivered the item during the noncontingent reinforcement condition, delivered the warning during the warning condition, delivered three high-p instructions during the high-p condition, and used hand-over-hand guidance in the extinction conditions (Eddie and Ricky). Integrity was 100% for all sessions for all participants. Interobserver agreement on integrity was collected during at least 25% of intervention sessions. Agreement was 100% for all participants.

Procedure

Separate paired-stimulus preference assessments (Fisher et al., 1992) were conducted to identify high-preference edible items and high- and low-preference play materials from an array of stimuli found in the children's classroom or home. The most preferred edible items for Eddie, Ricky, and Timmy were bread, candy, and a gummy bear, respectively. The most preferred play materials for Eddie, Ricky, and Timmy were a video, a large action figure, and a soft dart game, respectively. Low-preference play materials were a book, crayons and paper, and a stuffed animal for Eddie, Ricky, and Timmy, respectively. Finally, each child's nanny or teacher was asked to nominate a task that was not preferred by participants; teachers independently chose picking up items off the floor for Ricky and Timmy. Eddie's nanny chose going to the potty.

Functional Analysis

Three assessment conditions were presented in a multielement design. Each condition was presented as a trial. Each trial consisted of a 2-min preinstruction period, the presentation of the instruction, and a 3-min postinstruction period. At least six trials (two per each type of condition) were conducted per day with brief breaks between each; 36 trials were conducted in total. The order of trials was randomly determined.

In the preferred activity condition, participants engaged with high-preference play materials identified via the preference assessment. After 2 min, the therapist delivered the instruction to turn off the video (Eddie) or give me (experimenter) the toy (Ricky and Timmy). If the child complied, the experimenter said “thank you,” and the child was free to engage with low-preference play materials during the 3-min postinstruction period. If the child did not comply, the therapist did nothing (i.e., did not turn off the video or remove the toy) for the remainder of this 3-min period. This condition tested for maintenance via positive reinforcement because noncompliance resulted in continued access to high-preference play materials.

In the nonpreferred activity condition, low-preference play materials were available during the preinstruction period. After 2 min, the therapist delivered an instruction to complete the low-preference task (i.e., come to potty or pick up papers). If the child complied, the therapist said “thank you,” and the child was free to interact with low-preference play materials in the room for the remainder of the 3-min postinstruction period (typically 1.5 to 2 min). If the child did not comply, the experimenter did nothing (i.e., did not re-present the instruction or guide the participant to comply) for the remainder of the postinstruction period. This condition tested for maintenance via negative reinforcement because noncompliance resulted in avoidance of the nonpreferred activity.

In the control condition, low-preference play materials were available during the preinstruction period. After 2 min, the experimenter delivered an instruction to interact with the high-preference play materials (i.e., turn on the video [Eddie] or play with the high-preference toy [Ricky and Timmy]). If the child complied, the therapist said “thank you,” and the child had access to the high-preference material for the remainder of the 3-min postinstruction period. If the child did not comply, the therapist did nothing (i.e., did not turn on the video or give the child the toy) for the remainder of the 3-min period. This control condition eliminated events designed to evoke (low-preference task) and reinforce (contingent access to high-preference play materials) noncompliance in the preferred activity and nonpreferred activity test conditions.

Intervention Evaluation

Based on the functional analysis results, the nonpreferred activity condition (Eddie) and the preferred activity condition (Ricky and Timmy) were used as the context for the treatment evaluation. Although Timmy's functional analysis suggested maintenance via both positive and negative reinforcement, the positive reinforcement context was chosen because it was more consistent with problematic situations reported by his teacher.

Three antecedent interventions (i.e., noncontingent reinforcement, warning, and high-p instructional sequence) were evaluated with each child in reversal designs. In addition, extinction was evaluated for Eddie and Ricky. Each session consisted of either five (Eddie and Ricky) or three (Timmy) trials, and each trial consisted of a single instruction. Baseline sessions were identical to the nonpreferred activity condition (Eddie) or the preferred activity condition (Ricky and Timmy) of the functional analysis. During the three antecedent intervention phases, compliance resulted in experimenter praise. All children stayed in the session room during the 3-min postinstruction period and then received a brief break, as in baseline. Because Eddie's instruction involved going to the potty, breaks between his trials during baseline and intervention phases were longer (15 min) than those for Ricky and Timmy. If the child did not comply with the instruction, the therapist did nothing (i.e., did not guide the child to the potty; did not remove the toy) for the remainder of the 3-min postinstruction period (i.e., extinction was not in place).

During the noncontingent reinforcement condition, immediately following the initial instruction, the child was told that he could have a snack while performing the instructed activity, and the experimenter provided five small pieces of his high-preference edible item. Edible items were used instead of play materials because they were easier to consume while complying with the instruction. During the warning condition, the child was informed that he would have to end or begin another activity in 1 min (e.g., “in one minute, you have to give me the toy”). During the high-p instructional sequence, the experimenter presented three high-p instructions (i.e., “give me five,” “touch your nose,” and “what color is it?”) to the child, each 5 s apart. Five seconds after the third instruction, the target instruction (i.e., come to potty; give me the toy) was presented. Compliance with high-p instructions produced praise. All participants complied with all high-p instructions. During extinction (Eddie and Ricky), noncompliance with the initial instruction resulted in the experimenter repeating the instruction after 10 s and using hand-over-hand guidance to assist the participant in completing the task; extinction was procedurally identical.

Results and Discussion

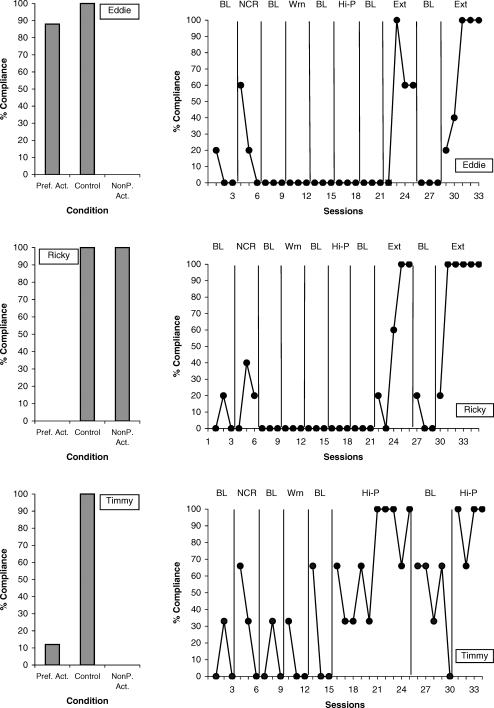

Figure 1 depicts the results of the functional analysis. Eddie displayed the lowest levels of compliance in the nonpreferred activity condition. Thus, it appeared that his noncompliance was evoked by the instruction to engage in a nonpreferred activity and was maintained by avoidance of that activity. Ricky displayed the lowest levels of compliance in the preferred activity condition. Thus, it appeared that his noncompliance was evoked by the instruction to terminate a preferred activity and was maintained by continued access to that activity. Timmy was compliant with few instructions delivered in both the nonpreferred and preferred activity conditions. It appeared that his noncompliance was evoked by both types of instructions and was maintained by avoidance of nonpreferred activities and access to preferred activities.

Figure 1.

Percentage of trials with compliance across the three conditions of the functional analysis for Eddie (top left), Ricky (middle left), and Timmy (bottom left). Percentage of trials with compliance during each session across baseline and intervention phases for Eddie (top right), Ricky (middle right), and Timmy (bottom right).

Figure 1 also depicts the results of the treatment evaluation. Results were similar for Eddie and Ricky, who showed high levels of compliance only when extinction was implemented. By contrast, Timmy complied at high levels when the high-p instructional sequence was implemented; therefore, extinction was not evaluated.

This study contributes to the literature on noncompliance by preschoolers in two ways. First, it enables identification of the specific mechanism responsible for the effects of extinction. In Cote et al. (2005), extinction was shown to be a necessary intervention component for all participants. However, because no functional analysis was conducted, it was unknown whether extinction improved compliance by eliminating escape or positive reinforcement for noncompliance. In the current study, the functional analysis enabled identification of the mechanism responsible for the effects of a procedurally identical extinction procedure across 2 participants. For Eddie, extinction was effective because it eliminated negative reinforcement for noncompliance; for Ricky, extinction was effective because it eliminated positive reinforcement for noncompliance.

Second, these results provide additional evidence that two commonly used antecedent interventions (warning and noncontingent reinforcement) are often ineffective and that extinction is frequently necessary to increase compliance in young children. It is interesting to note that, although the items used during noncontingent reinforcement were identified via a formal preference assessment in this study, the procedure was ineffective. Because individual antecedent interventions have been shown to be generally ineffective at increasing compliance in this and previous studies, one possibility for future research might be to combine several antecedent interventions to increase their power.

One limitation of this study is that, during the nonpreferred activity condition, noncompliance resulted in avoidance of a nonpreferred task and continued access to low-preference play materials. Thus, negative reinforcement was not isolated as a source of control. In addition, this assessment included a restricted variety of tasks, and some experimental conditions were evaluated only briefly.

References

- Cote C.A, Thompson R.H, McKerchar P.M. The effects of antecedent interventions and extinction on toddlers' compliance during transitions. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2005;38:235–238. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2005.143-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowther J.H, Bond L.A, Rolf J.E. The incidence, prevalence, and severity of behavior disorders among preschool-aged children in day care. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1981;9:23–42. doi: 10.1007/BF00917855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher W, Piazza C.C, Bowman L.G, Hagopian L.P, Owens J.C, Slevin I. A comparison of two approaches for identifying reinforcers for persons with severe and profound disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1992;25:491–498. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1992.25-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rortvedt A.K, Miltenberger R.G. Analysis of a high-probability instructional sequence and time-out in the treatment of child noncompliance. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994;27:327–330. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]