SUMMARY

Cell death pathways are likely regulated in specialized subcellular microdomains, but how this occurs is not understood. Here, we show that cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA) phosphorylates the Inhibitor of Apoptosis (IAP) protein survivin on Ser20 in the cytosol, but not in mitochondria. This phosphorylation event disrupts the binding interface between survivin and its antiapoptotic cofactor, XIAP. Conversely, mitochondrial survivin or a non-PKA phosphorylatable survivin mutant binds XIAP avidly, enhances XIAP stability, synergistically inhibits apoptosis, and accelerates tumor growth, in vivo. Therefore, differential phosphorylation of survivin by PKA in subcellular microdomains regulates tumor cell apoptosis via its interaction with XIAP.

Keywords: Survivin, apoptosis, PKA, mitochondria, XIAP, tumor growth

INTRODUCTION

Molecules of the Bcl-2 (Cory and Adams, 2002) or Inhibitor of Apoptosis (IAP) (Eckelman et al., 2006) gene family control programmed cell death, or apoptosis, as an essential requirement of cell and tissue homeostasis (Abrams, 2002). This process is orchestrated by multimolecular assembly of cell death effectors (Hengartner, 2000) that influence mitochondrial integrity (Shi, 2001), or death receptor signaling (Krammer, 2000), but how these processes are regulated in normal or tumor cells has remained largely unknown. This may involve post-translational modifications of apoptosis effectors, including phosphorylation/dephosphorylation (Amaravadi and Thompson, 2005), which in turn influence their stability (Maurer et al., 2006), subcellular targeting (Harada et al., 1999), and cell death function (Srivastava et al., 1998).

Survivin is a structurally unique IAP (Eckelman et al., 2006) that has been implicated in protection from apoptosis, control of cell division, and cellular adaptation to stress (Altieri, 2006). The roles of survivin at mitosis have been worked out in some detail, but how this molecule antagonizes cell death is less well understood (Altieri, 2006; Lens et al., 2006). Survivin cytoprotection may involve a pool of the molecule segregated in mitochondria (Caldas et al., 2005; Dohi et al., 2004a), and released in the cytosol in response to cell death stimuli (Dohi et al., 2004a). However, as for most IAPs, survivin does not directly inhibit caspase(s) (Eckelman et al., 2006), and its cytoprotective function appears to rely on interactions with other molecules, including the hepatitis B X-interacting protein (HBXIP) (Marusawa et al., 2003), and at least another IAP protein, XIAP (Dohi et al., 2004b). Determining how these putative antiapoptotic complexes are regulated in vivo, and why mitochondrial and cytosolic survivin differ with respect to cell death inhibition (Dohi et al., 2004a), is now a priority as deregulated IAP function aberrantly extends cell viability in cancer, and molecular antagonists of IAPs are being tested as novel anticancer regimens in patients (Reed, 2003).

As a pivotal integrator of multiple signaling networks, cyclic AMP (cAMP)-dependent protein kinase A (PKA) (Hardie, 2004; Taylor et al., 2004), participates in cell death. PKA is a Ser/Thr kinase organized as a tetrameric holoenzyme composed of two catalytic (C) subunits that are maintained in an inactive conformation by two regulatory (R) subunits (RIα/β and RIIα/β) (Taylor et al., 2004). Binding of cAMP enables enzymatic activity via release of the C subunits, whereas compartmentalization of PKA signaling in specialized subcellular microenvironments is contributed by the scaffolding function of A-kinase anchoring proteins (Gold et al., 2006; Kinderman et al., 2006), which promote assembly of RII, or RII/RI subunits, and differential recruitment of signal transduction or signal termination cofactors (Wong and Scott, 2004). PKA activity has been variously associated with increased cell survival via phosphorylation and cytoplasmic trapping of proapoptotic Bad (Harada et al., 1999; Virdee et al., 2000), or, conversely, induction of apoptosis, by promoting phosphorylation-dependent nuclear import of the cell death agonist, Par-4 (Gurumurthy et al., 2005), or neutralization of Bcl-2-Bax complexes (Srivastava et al., 1998).

In this study, we dissected the molecular requirements of IAP cytoprotection, and their relevance to tumor growth.

RESULTS

Identification of novel PKA phosphorylation sites in survivin

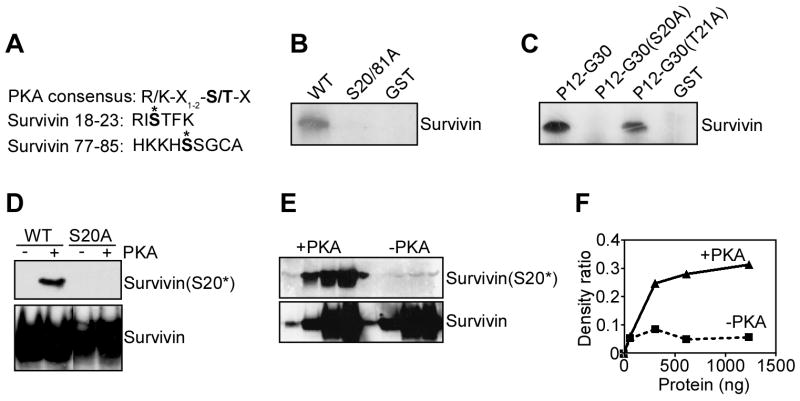

Inspection of the survivin sequence revealed that Ser20 (S20) and Ser81 (S81) matched the consensus R/KX1-2-S/T-X as potential phosphorylation sites for PKA (Figure 1A). In a kinase assay, PKA phosphorylated wild type (WT) survivin, but not a survivin Ser20/81Ala (S20/81A) double mutant (Figure 1B), suggesting that both residues could be substrates for PKA. In addition, PKA phosphorylated a synthetic peptide duplicating the survivin sequences Pro12-Gly30 (P12-G30), thus containing S20 (Figure 1C). In contrast, substitution of S20 to A abolished PKA phosphorylation of this peptide in a kinase assay (Figure 1C). Conversely, PKA phosphorylated a control Thr21Ala (T21A) survivin mutant peptide with substitution of a potential Thr phosphorylation site (Figure 1C). Although PKA phosphorylated survivin on S81 in a kinase assay (not shown), no clear phosphorylation on this residue was detected using a S81 phospho-specific antibody, in vivo (see below). Therefore, a role of S81 as a PKA phosphorylation site was not further investigated.

Figure 1. Phosphorylation of survivin by PKA.

A. Sequence analysis. The consensus PKA phosphorylation site and survivin sequences between residues 18-23 or 77-85 are shown. Putative PKA phosphorylation sites on survivin S20 and S81 are indicated with an asterisk. B. PKA phosphorylation of survivin, in vitro. Recombinant wild type (WT) survivin, GST or S20/81A survivin double mutant was incubated in a kinase assay in the presence of PKA and 32P-γATP. Phosphorylated bands were detected by autoradiography. C. PKA phosphorylation of survivin peptides. A synthetic peptide duplicating the survivin sequence P12-G30 with or without S20A or T21A substitutions was incubated with PKA in a kinase assay and radioactive bands were detected by autoradiography. D. Characterization of a survivin phospho-specific antibody to S20. Recombinant WT survivin or PKA phosphorylation-defective S20A survivin was incubated in a PKA kinase assay in the presence of unlabeled phosphate, and analyzed by Western blotting with a S20 phospho-specific antibody (Survivin(S20*)), or an antibody to unmodified survivin (Survivin). Survivin(S20*), Survivin phosphorylated on S20. E. Concentration-dependence. Increasing concentrations of recombinant WT survivin (0.06, 0.3, 0.6, 1.2 μg) were incubated in a PKA kinase assay in the presence of unlabeled phosphate, and analyzed by Western blotting. F. Densitometry. Protein bands from the experiment in E were quantified by densitometry and expressed as ratio in the presence or absence of PKA phosphorylation.

To determine whether PKA phosphorylated survivin in vivo, we generated a rabbit polyclonal antibody to a survivin peptide containing chemically phosphorylated S20, and sequentially affinity-purified the immune sera over non-phosphorylated and phosphorylated survivin peptide-Sepharose columns. The phospho-specific antibody to S20 reacted with WT survivin phosphorylated in vitro by PKA, but not with a S20A phosphorylation-defective survivin mutant (Figure 1D). No reactivity of the S20 phospho-specific antibody with WT or mutant survivin was observed in the absence of PKA (Figure 1D). In contrast, an antibody to unmodified survivin indistinguishably recognized unphosphorylated or PKA-phosphorylated WT or mutant survivin (Figure 1D). Similarly, the S20 phospho-specific antibody reacted with PKA-phosphorylated survivin in a concentration-dependent manner, whereas non-phosphorylated survivin was unreactive (Figure 1E). Densitometric quantification of protein bands confirmed the concentration-dependent recognition of the S20-phospho-specific antibody for PKA-phosphorylated survivin, as compared with the unphosphorylated protein (Figure 1F).

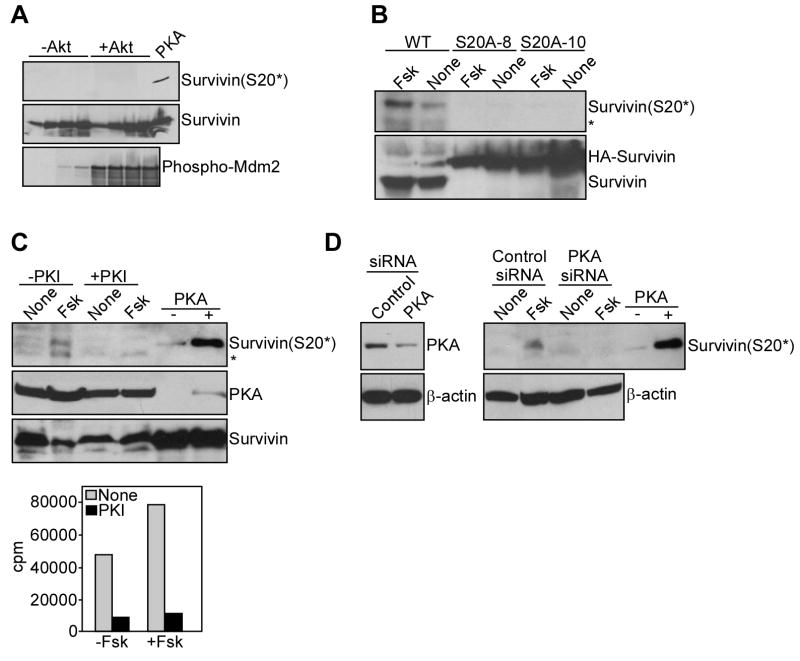

Characterization of PKA as a survivin S20 kinase, in vivo

To begin investigating the role of PKA as a survivin S20 kinase, we first asked whether other Ser/Thr kinases involved in cell death regulation could phosphorylate this residue. In these experiments, Akt did not phosphorylate survivin on S20 (Figure 2A), whereas it readily phosphorylated the p53 regulator, Mdm2 (Figure 2A). Next, we stimulated PKA activity with forskolin in stably transfected INS-1 insulinoma cells, and looked for changes in survivin S20 phosphorylation. A basal level of S20 phosphorylation was observed in INS-1 cells expressing WT survivin (Figure 2B). Stimulation of these cells with forskolin resulted in further increased phosphorylation of survivin on S20, whereas no constitutive or forskolin-induced S20 phosphorylation was detected in two independent INS-1 clones expressing a S20A phosphorylation-defective survivin mutant (Figure 2B). We next used pharmacologic or genetic approaches to target PKA activity in INS-1 cells. First, inhibition of PKA enzymatic activity with the PKI peptide (Gurumurthy et al., 2005) completely inhibited forskolin-induced S20 phosphorylation of survivin in INS-1 cells (Figure 2C, top panel). Conversely, PKI did not affect PKA or survivin protein levels in treated cultures (Figure 2C, top panel). In control experiments, PKI completely suppressed PKA enzymatic activity in the presence or absence of forskolin (Figure 2C, bottom panel). Second, we acutely ablated PKA expression in INS-1 cells by small interfering RNA (siRNA), and looked for changes in S20 phosphorylation of survivin. Transfection of these cells with non-targeted siRNA did not affect PKA expression or survivin phosphorylation on S20 stimulated by forskolin (Figure 2D). In contrast, siRNA targeting of PKA efficiently reduced PKA levels in INS-1 cells, and abolished forskolin-induced S20 phosphorylation of survivin (Figure 2D).

Figure 2. Identification of PKA as a survivin S20 kinase, in vivo.

A. Akt kinase assay. Increasing concentrations of recombinant WT survivin (0.06, 0.3, 0.6, 1.2 μg) were incubated in an Akt-1 kinase assay in the presence of unlabeled phosphate, and analyzed by Western blotting. Akt phosphorylation of recombinant Mdm2 (S166) was used as a control. B. Effect of forskolin. INS-1 cells stably expressing WT survivin or S20A survivin (clones #8 and #10) were treated with the PKA activator, forskolin (Fsk) and analyzed by Western blotting. *, non specific. C. Effect of PKI. Top panel, INS-1 cells expressing WT survivin were treated with or without Fsk in the presence or absence of the PKA inhibitor, PKI, and analyzed by Western blotting. Bottom panel, PKA activity in the presence or absence of Fsk. *, non-specific. D. siRNA silencing of PKA. INS-1 cells expressing WT survivin were transfected with non-targeted (control) or PKA-directed siRNA, treated with or without Fsk, and analyzed by Western blotting. For panels A, C, D, a kinase assay with recombinant survivin in the presence or absence of PKA was used as a control.

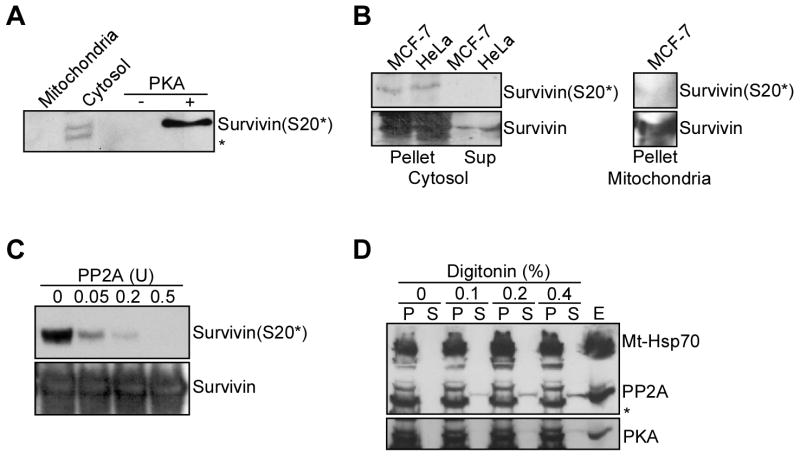

Differential subcellular compartmentalization of PKA phosphorylation of survivin

Survivin exists in individual subcellular pools that are separately implicated in mitotic control (nuclei) or cytoprotection (mitochondria) (Colnaghi et al., 2006; Fortugno et al., 2002). Therefore, we next asked whether PKA differentially phosphorylated the distinct survivin pools. By comparative Western blotting, S20 phosphorylated survivin was detected exclusively in isolated cytosolic, but not mitochondrial extracts (Figure 3A). Consistent with this, cytosolic survivin immunoprecipitated from HeLa or MCF-7 cell extracts reacted with the S20 phospho-specific antibody, by Western blotting (Figure 3B). Conversely, survivin immunoprecipitated from isolated mitochondrial extracts was not phosphorylated on S20 (Figure 3B). We next studied a potential basis for the differential phosphorylation of survivin in cytosol versus mitochondria. We found that purified protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) readily dephosphorylated PKA-phosphorylated recombinant survivin on S20, in vitro (Figure 3C). Isolated mitochondrial extracts contained PP2A-reactive material (not shown) (Janssens et al., 2005), and this was progressively released in the supernatant after mitochondrial permeabilization with digitonin (Figure 3D). Therefore, in addition to localizing to the outer mitochondrial membrane (Janssens et al., 2005), a fraction of PP2A is present in the mitochondrial intermembrane space, which also contains survivin (Dohi et al., 2004a). Conversely, a mitochondrial matrix protein, mt-Hsp70, was not released in the supernatant of digitonin-permeabilized mitochondria (Figure 3D), and, similarly, PKA reactivity did not redistribute to the mitochondrial intermembrane space after digitonin treatment (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. Differential subcellular phosphorylation of survivin by PKA.

A. Subcellular compartmentalization of survivin phosphorylation on S20. MCF-7 cells were fractionated in cytosolic or mitochondrial extracts, and analyzed by Western blotting. A kinase assay with recombinant survivin in the presence or absence of PKA was used as a control. *, non specific. B. Immunoprecipitation. Survivin was immunoprecipitated from cytosolic (left panel) or mitochondrial (right panel) extracts, and pellets or supernatants were analyzed by Western blotting. C. Effect of PP2A. PKA-phosphorylated recombinant survivin was mixed with the indicated increasing concentrations of PP2A, and analyzed by Western blotting. COX-IV was used as a mitochondrial marker. D. Submitochondrial fractionation. Isolated mitochondrial extracts treated with proteinase K were incubated with the indicated increasing concentrations of digitonin, and aliquots of pellets (P) or supernatants (S) were analyzed by Western blotting. E, total cell extracts. *, non specific. Bottom panel, submitochondrial localization of PKA.

Mitochondrial survivin selectively associates with XIAP

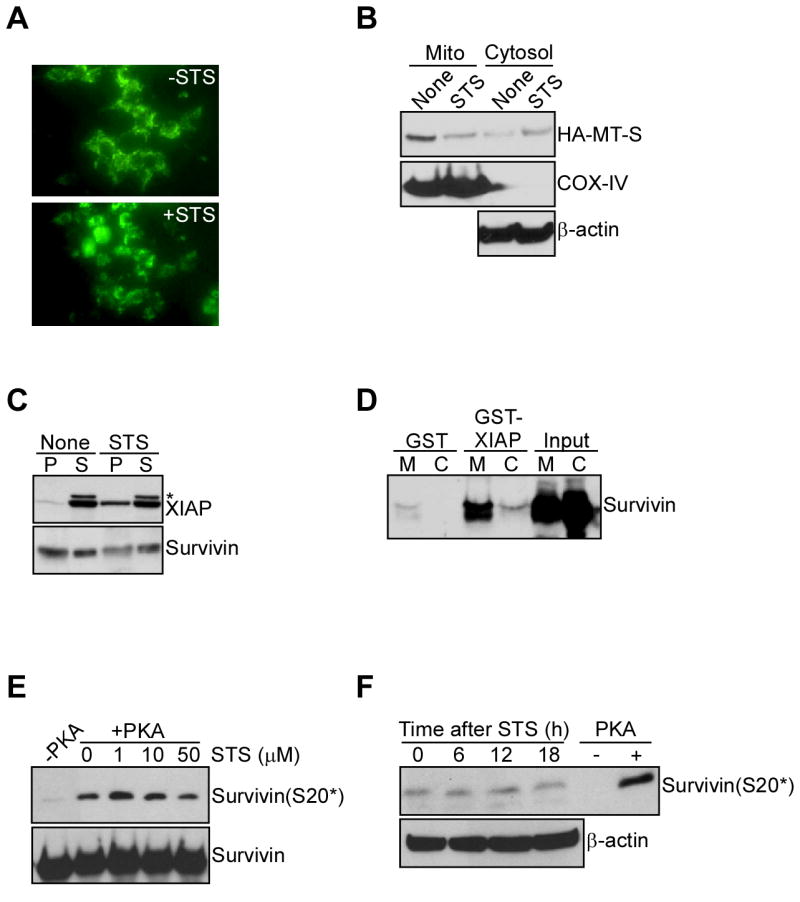

Cell death stimuli release mitochondrial survivin in the cytosol, which in turn results in apoptosis inhibition (Dohi et al., 2004a). As this pathway may involve binding of survivin to an antiapoptotic cofactor, i.e. XIAP (Dohi et al., 2004b), we first asked whether mitochondria-derived survivin selectively associated with XIAP. Upon exposure to a cell death stimulus, staurosporine (STS), INS-1 cells expressing GFP-survivin targeted to mitochondria (Dohi et al., 2004a) exhibited redistribution of the GFP signal from a punctate, perinuclear pattern to a diffuse cytosolic staining, by fluorescence microscopy (Figure 4A). This coincided with nearly complete depletion of mitochondria-associated survivin, and concomitant increase in cytosol-localized survivin, by Western blotting with an antibody to HA (Figure 4B). In addition, survivin immunoprecipitated from cytosolic extracts isolated from STS-treated MCF-7 cells was found in complex with endogenous XIAP (Figure 4C). In contrast, survivin immunoprecipitated from cytosolic extracts of untreated MCF-7 cells did not associate with XIAP (Figure 4C). Consistent with this, GST-XIAP strongly bound endogenous survivin in isolated mitochondrial extracts in pull down experiments, in vivo (Figure 4D). Conversely, survivin isolated from cytosol fractions bound negligibly to XIAP, and GST alone did not associate with survivin in mitochondrial or cytosol extracts (Figure 4D). Because STS is a broad spectrum kinase inhibitor, we next asked whether it could affect PKA phosphorylation of survivin on S20, in vitro or in vivo. In a kinase assay, concentrations of STS up to 50 μM did not reduce PKA phosphorylation of survivin on S20 (Figure 4E). In addition, survivin phosphorylation on S20 was not significantly affected in INS-1 cells exposed to STS throughout an 18-h time interval, in vivo (Figure 4F).

Figure 4. Complex formation between mitochondrial survivin and XIAP.

A. Mitochondrial discharge of survivin during cell death. INS-1 cells stably expressing mitochondrially-targeted survivin fused to GFP were treated with or without staurosporine (STS), and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy after 8 h. B. Western blotting. INS-1 cells expressing HA-tagged mitochondrially-targeted survivin (HA-MT-S) were treated with STS, and mitochondrial (Mito) or cytosolic extracts were analyzed by Western blotting. C. Immunoprecipitation. Cytosolic extracts from untreated (None) or STS-treated MCF-7 cells were immunoprecipitated with an antibody to survivin, and pellets (P) or supernatants (S) were analyzed by Western blotting. *, non specific. D. In vivo capture assay. Mitochondrial (M) or cytosolic (C) extracts from MCF-7 cells were incubated with GST or GST-XIAP, and bound proteins were analyzed by Western blotting. E. Effect of STS on survivin S20 phosphorylation, in vitro. Recombinant survivin in a PKA kinase assay was incubated with the indicated concentrations of STS, and analyzed by Western blotting. F. Time-course. INS-1 cells stably expressing WT survivin were treated with STS, harvested at the indicated time intervals and analyzed for survivin phosphorylation on S20. A kinase assay with recombinant survivin in the presence or absence of PKA was used as a control.

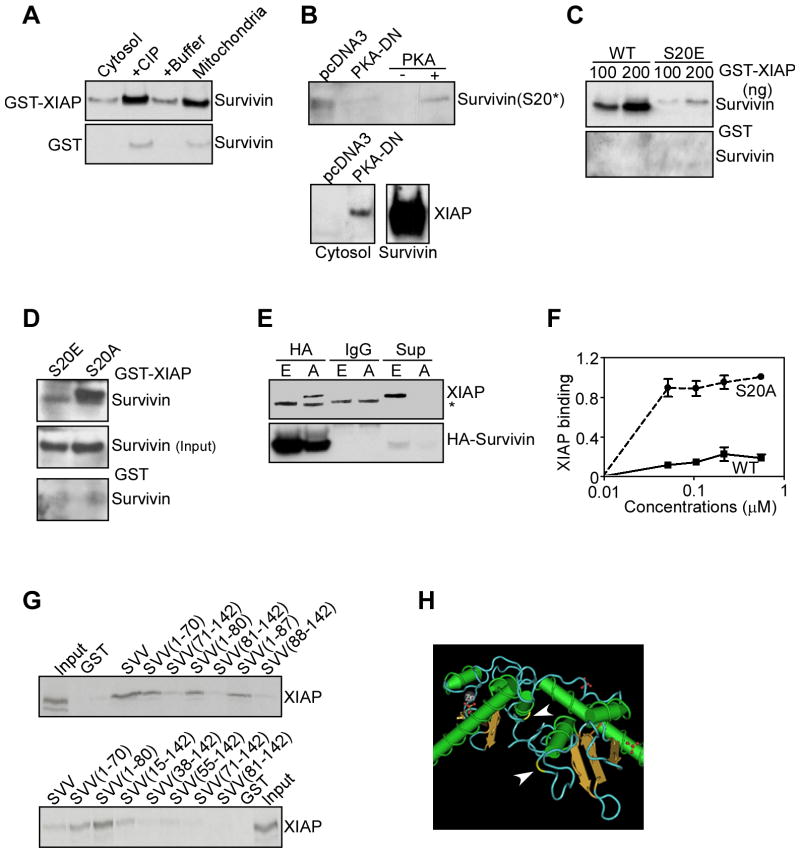

PKA regulation of compartmentalized survivin-XIAP complex

We next asked whether differential PKA phosphorylation of survivin in individual subcellular compartments regulated its interaction with XIAP. GST-XIAP minimally associated with survivin in isolated cytosolic fractions (Figure 5A), in agreement with the data presented above. However, treatment with calf intestinal phosphatase promoted strong binding of cytosolic survivin to XIAP (Figure 5A), suggesting that a phosphorylation event interfered with the formation of a survivin-XIAP complex. In control experiments, GST-XIAP strongly bound survivin in mitochondrial extracts, whereas no interaction between GST and cytosolic or mitochondrial survivin was observed in the presence or absence of phosphatase (Figure 5A). Consistent with these data, transfection of MCF-7 cells with a PKA dominant negative (DN) mutant cDNA completely suppressed PKA phosphorylation of survivin on S20, in vivo, whereas a control vector was ineffective (Figure 5B, top panel). This was associated with de novo formation of a survivin-XIAP complex in cells transfected with PKA-DN, but not control vector (Figure 5B, bottom panel).

Figure 5. PKA regulation of survivin-XIAP complex.

A. Phosphatase treatment. Cytosolic extracts from MCF-7 cells were treated with buffer or calf intestinal phosphatase (CIP), mixed with GST or GST-XIAP, and bound proteins were analyzed by Western blotting. Untreated mitochondrial extracts were used as control. B. Effect of PKA dominant negative (DN) mutant. MCF-7 cells were transfected with pcDNA3 or a PKA-DN cDNA, immunoprecipitated with an antibody to survivin, and immune complexes were analyzed by Western blotting. A kinase assay with recombinant survivin in the presence or absence of PKA was used as a control. Recombinant survivin was used as a control for XIAP binding. C. Differential survivin-XIAP interaction, in vitro. Increasing concentrations of WT survivin or S20E survivin were incubated with GST-XIAP (top panel) or GST (bottom panel), and bound proteins were analyzed by Western blotting. D. In vivo capture assay. Cytosolic extracts from MCF-7 cells transfected with S20A or S20E survivin were incubated with GST-XIAP (top panel) or GST (bottom panel), and bound proteins were analyzed by Western blotting. E. Co-immunoprecipitation. MCF-7 cells expressing HA-tagged S20A (A) or S20E (E) survivin were immunoprecipitated with IgG or an antibody to HA, and the immune complexes were analyzed by Western blotting. F. PKA modulation of survivin-XIAP affinity. WT survivin or S20A survivin was incubated in a PKA kinase assay with unlabeled phosphate, and binding to recombinant XIAP was analyzed by Western blotting. Data are expressed as the ratio between phosphorylated and unphosphorylated survivin binding to XIAP, and are the mean±SEM of three independent experiments. G. Survivin-XIAP binding site. The indicated survivin mutants were expressed as GST-fusion proteins, incubated with 35S-labeled XIAP, and bound proteins were analyzed by autoradiography. H. Localization of S20 in the survivin crystal structure. Arrows indicate the position of Ser20 (yellow) in each survivin monomer.

Next, we used different survivin mutants that lack (S20A) or mimic (S20E) the PKA phosphorylation site on S20, and tested their differential association with XIAP. In control experiments, recombinant WT survivin bound GST-XIAP in a concentration-dependent manner, whereas S20E survivin minimally associated with XIAP, in vitro, and control GST was unreactive (Figure 5C). Accordingly, XIAP strongly bound S20A, but not S20E survivin, in a capture assay (Figure 5D), as well as in co-immunoprecipitation experiments, in vivo (Figure 5E), whereas control GST or IgG immune complexes were ineffective (Figure 5D-E). Consistent with this, recombinant WT survivin phosphorylated in vitro by PKA exhibited negligible affinity for XIAP, by densitometric quantification of pull down experiments, in vitro (Figure 5F). Conversely, S20A survivin strongly bound XIAP in a concentration-dependent and saturable manner, regardless of PKA phosphorylation (Figure 5F).

We next asked whether S20 in survivin was part of a physical binding site for XIAP. In pull down experiments, full length survivin, but not GST associated with 35S-labeled recombinant XIAP (Figure 5G). In domain mapping studies, XIAP bound survivin fragments comprising Baculovirus IAP Repeat (BIR) (Verdecia et al., 2000) residues 1-70, 1-80 and 1-87 (Figure 5G). In contrast, no interaction between XIAP and survivin fragments containing COOH-terminus residues 81-142 and 88-142 was observed (Figure 5G). To further narrow a survivin-XIAP binding interface, smaller BIR-containing fragments of survivin were analyzed in pull down experiments. In addition to full-length survivin and the survivin BIR (residues 1-80), XIAP bound a survivin fragment comprising residues 15-142, whereas a region containing the sequence 38-142 was ineffective (Figure 5G). Similarly, survivin fragments originating downstream of Met38, including 55-142, 71-142 or 81-142, did not bind XIAP (Figure 5F). Therefore, a minimal survivin binding interface for XIAP comprises BIR residues 15-38, thus encompassing S20. In the survivin crystal structure (Verdecia et al., 2000), S20 localizes to a flexible, surface-exposed loop connecting α2 and α3 of the BIR (Figure 5H).

PKA regulation of an antiapoptotic survivin-XIAP complex

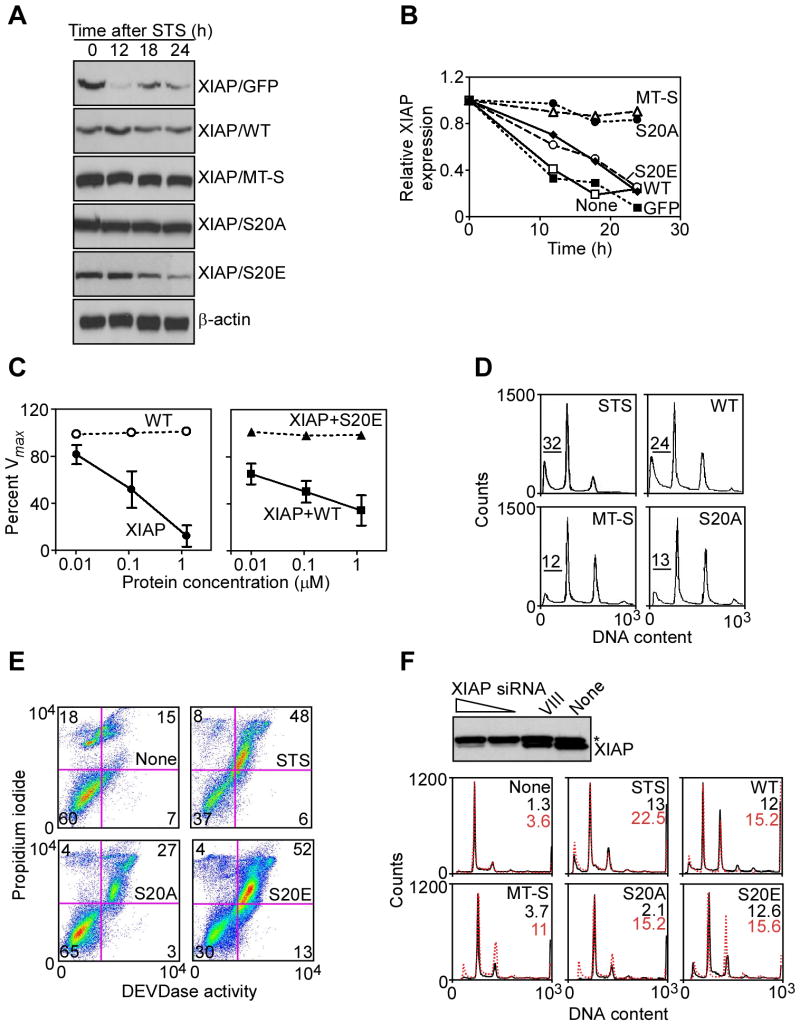

INS-1 cells transduced with a replication-defective adenovirus encoding GFP (pAd-GFP), and exposed to STS exhibited time-dependent decrease in endogenous XIAP levels (Figure 6A, B). This reaction was unaffected by expression of WT survivin (Figure 6A, B), which in these cells can not be transported to mitochondria, and therefore is not cytoprotective (Dohi et al., 2004b). Conversely, expression of mitochondrially-targeted survivin (MT-S) in INS-1 cells treated with STS prevented XIAP degradation throughout a 24-h time interval (Figure 6A, B). Under these experimental conditions, INS-1 cells stably transfected with S20A survivin also exhibited increased XIAP stability after STS treatment (Figure 6A, B). In contrast, stable expression of S20E survivin did not restore XIAP expression during STS-induced cell death (Figure 6A, B). Next, we studied the effect of PKA phosphorylation of survivin on inhibition of caspase activity using recombinant proteins in a cell-free system. Increasing concentrations of survivin alone did not reduce caspase-3 activity, whereas XIAP suppressed caspase-3 activity in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 6C), in agreement with previous observations (Eckelman et al., 2006). Addition of recombinant survivin to a suboptimal (10 nM) concentration of XIAP that produce ∼20% reduction in caspase activity, synergistically suppressed caspase-3 activity in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 6C). In contrast, addition of comparable concentrations of S20E survivin did not enhance XIAP inhibition of caspase-3 activity (Figure 6C).

Figure 6. PKA regulation of IAP cytoprotection.

A. Modulation of XIAP stability. INS-1 cells expressing GFP, survivin (WT), mitochondrially-targeted survivin (MT-S), or S20A or S20E survivin were exposed to STS, and extracts were analyzed by Western blotting at the indicated time intervals. B. Quantification of XIAP stability. Protein band intensity of the experiment in A was quantified by densitometry. C. Modulation of caspase activity. Recombinant XIAP, WT or S20E survivin was mixed alone (left panel) or in combination (right panel) with Apaf-1, dATP and cytochrome c, and analyzed for DEVDase activity. For combination experiments, a suboptimal concentration of XIAP (0.01 μM) was used. Data are the mean±SEM of three independent experiments. D. DNA content analysis. INS-1 stably transfected with the indicated cDNAs were exposed to STS, and analyzed for DNA content by propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry. The percentage of cells with hypodiploid DNA content is indicated. MT-S, mitochondrially-targeted survivin. E. Multiparametric flow cytometry. INS-1 transfectants stably expressing pcDNA3 (top panels) or S20A or S20E survivin (bottom panels) were treated with STS, and simultaneously analyzed for caspase activity (DEVDase activity) and propidium iodide staining by multiparametric flow cytometry. The percentage of cells in each quadrant is indicated. F. XIAP knockdown. INS-1 cells were transfected with non-targeted dsRNA oligonucleotide (VIII) or increasing concentrations of XIAP-directed siRNA, and analyzed by Western blotting (top panel). *, non specific. Cells stably expressing the indicated constructs were transfected with control (VIII) or XIAP-directed siRNA, exposed to STS, and analyzed for DNA content by propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry (bottom panel). Black line, control siRNA, red line, XIAP siRNA. The percentage of cells with hypodiploid DNA content is indicated.

We then asked whether PKA regulation of a survivin-XIAP complex affected tumor cell apoptosis. For these experiments, we used stably transfected INS-1 cells that do not express mitochondrial survivin (Dohi et al., 2004a). STS treatment induced INS-1 cell apoptosis, by hypodiploid DNA content and flow cytometry, and this reaction was not significantly affected by WT survivin (Figure 6D). In contrast, expression of mitochondrially-targeted survivin (MT-S) nearly completely rescued INS-1 cells from STS-induced cell death (Figure 6D). Stable expression of S20A survivin in INS-1 cells circumvented the requirement of mitochondrial import of survivin, and inhibited STS-induced apoptosis indistinguishably from mitochondrially-targeted survivin (Figure 6D). To validate genuine suppression of apoptosis under these conditions, we next studied changes in caspase activity, in vivo. STS induced increased caspase activity and apoptosis in INS-1 cells, by flow cytometry analysis of DEVD hydrolysis and propidium iodide staining (Figure 6E). Consistent with the data reported above, expression of S20A survivin efficiently inhibited STS-induced cell death in INS-1 cultures, and nearly doubled the number of viable cells (Figure 6E). In contrast, S20E survivin had no effect on STS-induced INS-1 cell death (Figure 6E). To confirm that PKA regulation of survivin cytoprotection was dependent on XIAP, we acutely ablated XIAP expression in INS-1 cells by siRNA, and analyzed cell death responses. Transfection of INS-1 cells with XIAP-directed siRNA efficiently suppressed XIAP expression, whereas a control dsRNA oligonucleotide (VIII) had no effect (Figure 6F). In cells transfected with control siRNA, STS-induced apoptosis was unaffected by WT survivin, whereas expression of mitochondrially-targeted survivin (MT-S) or S20A survivin significantly attenuated cell death (Figure 6F). Conversely, knockdown of XIAP nearly completely reversed cytoprotection by MT-S and S20A survivin against STS-induced apoptosis (Figure 6F). In these experiments, expression of S20E survivin had no effect on STS-induced apoptosis, in the presence or absence of XIAP knockdown (Figure 6F).

PKA regulation of IAP cytoprotection influences tumor growth

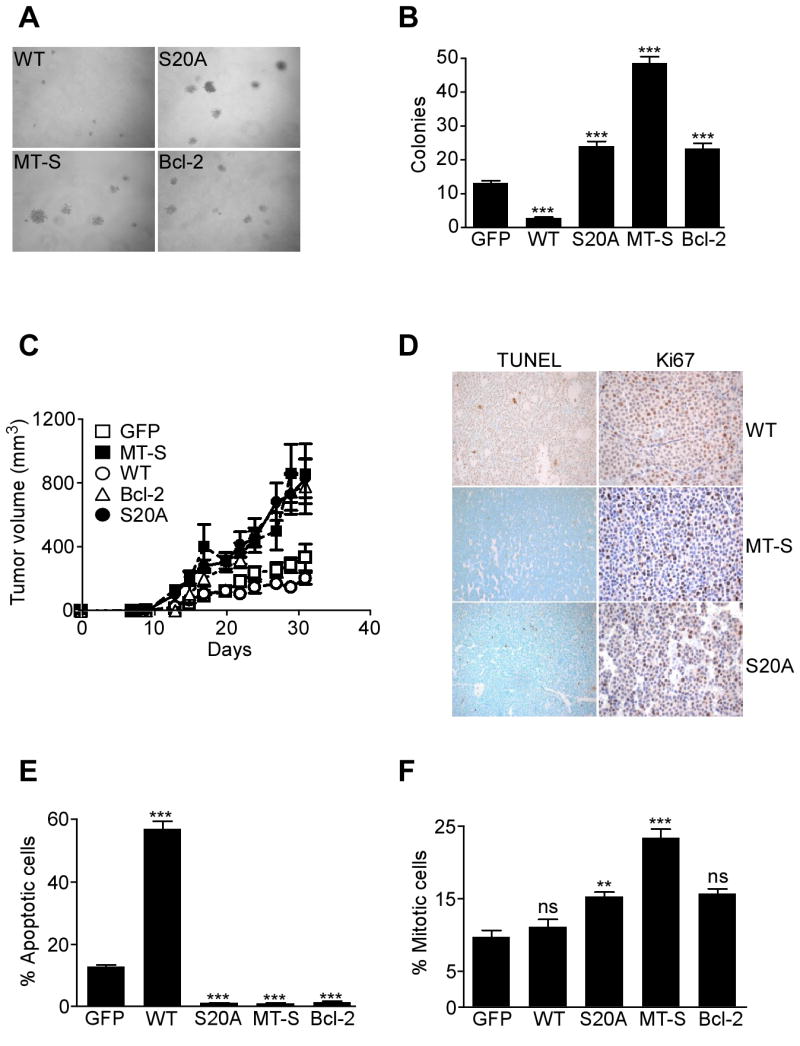

We next asked whether compartmentalized modulation of IAP-IAP cell survival by PKA affected tumor cell responses, in vitro and in vivo. First, we analyzed colony formation in soft agar, i.e. anchorage-independent growth of INS-1 cells expressing various cDNA constructs. INS-1 cells expressing WT survivin exhibited virtually no colony formation in soft agar, whereas a background number of colonies was formed by INS-1 cells stably expressing GFP (Figure 7A, B). This is consistent with earlier results (Dohi et al., 2004a), suggesting that over-expression of survivin as a mitotic regulator in not fully transformed cells, i.e. INS-1, causes checkpoint activation and reduced cell viability. Conversely, stable expression of mitochondrially-targeted survivin (MT-S) caused a 4- to 5-fold increased number of INS-1 colonies (Figure 7A, B). Expression of S20A survivin also resulted in increased colony formation in soft agar, quantitatively similar to the effect mediated by stable expression of Bcl-2 in these cells (Figure 7A, B).

Figure 7. PKA regulated IAP cytoprotection influences tumor growth.

A, B. Colony formation assay. Colonies formed in semisolid medium by INS-1 cells stably expressing WT survivin, S20A survivin, mitochondrially-targeted survivin (MT-S) or Bcl-2 were visualized by phase contrast microscopy (A), and scored in individual high-power fields (B). Data are the mean±SEM of four independent experiments. C. Kinetics of tumor growth. INS-1 cells stably expressing the indicated constructs were injected s.c. in the flanks of immunocompromised mice and tumor growth was measured at the indicated time intervals. MT-S, mitochondrially-targeted survivin. Data are the mean±SEM of individual tumor groups (n=8). D. Histology. The various INS-1 tumors in C were analyzed for apoptosis by TUNEL staining, or cell proliferation by Ki67 labeling. Magnification, ×100. E. Apoptotic index. Quantification of TUNEL+ cells in INS-1 tumors. F. Mitotic index. Quantification of Ki67+ cells in INS-1 tumors. For panels E, F, data are the mean±SEM of an average of 800 cells. ***, p<0.0001; ns, not significant.

Next, we injected stably transfected INS-1 cells in immunocompromised mice, and analyzed kinetics of tumor growth, in vivo. INS-1 cells expressing GFP or WT survivin formed small superficial tumors in SCID/beige mice, which did not significantly increase in size throughout a two-week interval (Figure 7C). Conversely, expression of mitochondrially-targeted survivin (MT-S) or Bcl-2 promoted exponential INS-1 tumor growth, in vivo (Figure 7C). A quantitatively similar enhancement of tumor growth was observed with INS-1 expressing S20 survivin (Figure 7C). Immunohistochemical analysis of the various tumors collected at the end of the experiment revealed that expression of WT survivin produced no changes in mitotic index, but dramatically increased the number of apoptotic cells, by TUNEL staining, in vivo (Figure 7D-F). In contrast, expression of mitochondrially-targeted survivin, Bcl-2 or S20A survivin nearly completely abolished tumor cell apoptosis, in vivo (Figure 7D, E). Except for mitochondrially-targeted survivin, which moderately increased the mitotic index of INS-1 tumors, expression of S20A survivin or Bcl-2 did not significantly affect tumor cell proliferation, in vivo (Figure 7D, F).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have described a cytoprotective pathway centered on intermolecular cooperation between two IAP proteins, survivin and XIAP, and showed that this process is negatively regulated by compartmentalized PKA phosphorylation of survivin on S20 in the cytosol, but not mitochondria. Non-PKA phosphorylatable survivin binds XIAP avidly, and this complex exhibits increased stability against degradation during cell death, synergistically inhibits caspase activity, and promotes exponential tumor growth, in vivo.

Although originally thought of as endogenous caspase inhibitors, we now know that most, perhaps all IAPs except XIAP, do not inhibit caspases in vivo, due to instability of interactions, changes in critical contact sites, or preference for caspase destruction, rather than catalytic inhibition (Eckelman et al., 2006). A model of IAP-IAP intermolecular cooperation as proposed here may provide an alternative mechanistic basis for the cytoprotective activity of these proteins, and, more broadly, for other functions assigned to IAPs, in vivo. In the case of a survivin-XIAP complex, this plays a pivotal antiapoptotic role, especially during tumor growth in vivo, whereas a cIAP1-survivin interaction may be primarily involved in cell division, regulating chromosome segregation and cytokinesis (Samuel et al., 2005). Several lines of evidence presented here identify PKA as a survivin S20 kinase, in vivo. These include the ability of forskolin, a PKA activator, to enhance a basal level of survivin phosphorylation on S20, whereas pharmacologic, molecular or genetic targeting of PKA all independently abrogated this phosphorylation step, in vivo.

A critical aspect of this pathway is its differential regulation in specialized subcellular microenvironments, in particular cytosol versus mitochondria. Although it has been speculated that cell death cascades do not assemble randomly in cells, but involve regulated, “four-dimensional” trafficking among spatial microenvironments (Porter, 1999), including mitochondria (Shi, 2001), and the cell surface (Krammer, 2000), the molecular requirements of these processes have not been elucidated. Here, PKA phosphorylation of survivin on S20 resulted in loss of binding to its antiapoptotic cofactor, XIAP (Dohi et al., 2004b), a mechanism not previously recognized for regulation of IAP function (Eckelman et al., 2006), or other cell death effectors. S20 is embedded in a surface-exposed loop in the survivin BIR (Verdecia et al., 2000), and phosphorylation on this site may affect the conformation and/or charge of the XIAP binding interface comprised between residues 15-38 resulting in reduced affinity for protein recognition. Differently from other mechanisms of phosphorylation-dependent trafficking of apoptosis effectors (Deng et al., 2003), PKA phosphorylated survivin in the cytosol, but not in mitochondria. This subcellular compartmentalization explains why mitochondrial survivin is earmarked to inhibit apoptosis (Caldas et al., 2005; Dohi et al., 2004a), being competent to associate with XIAP upon discharge from mitochondria, and enhancing both the stability and caspase inhibitory properties of the IAP-IAP complex during cell death. In the model of INS-1 cells, in which survivin can not be transported to mitochondria, and therefore is not cytoprotective (Dohi et al., 2004a), expression of non-PKA phosphorylatable survivin completely bypassed the requirement of mitochondrial localization, and efficiently inhibited apoptosis in vitro and in vivo in a XIAP-dependent manner.

The mechanism(s) by which survivin remains unphosphorylated on S20 in mitochondria need to be further elucidated. It is possible that the proximity of survivin and a pool of the Ser/Thr phosphatase PP2A (Janssens et al., 2005) in the mitochondrial intermembrane space, together with the absence of PKA in this compartment, and the ability of PP2A to dephosphorylate survivin on S20, may all contribute to maintain mitochondrial survivin dephosphorylated on this residue. In addition, PKA signaling in mitochondria is highly compartmentalized, and A kinase anchoring proteins, including WAVE1 and D-AKAP1 have been shown to target PKA to the outer mitochondrial membrane (Wong and Scott, 2004), thus further contributing to its physical separation from survivin in the intermembrane space (Dohi et al., 2004a). In this context, the ability of tumor cells to preferentially accumulate survivin to mitochondria as compared to normal tissues (Dohi et al., 2004a) may signal not only compartmentalization of a cell death antagonist in the microenvironment of cell death initiation (Shi, 2001), but also a mechanism to elude negative regulation by PKA in the cytosol.

The pathway described here may have broad pathophysiological implications for mechanisms of tumor growth, in vivo. Although IAPs, especially survivin and XIAP, have been recognized for their role in tumor formation, and are targets for cancer therapeutics (Altieri, 2003; Wright and Duckett, 2005), the implications of PP2A and PKA signaling in transformed cells have remained elusive, and, at times, conflicting. Proposed to function as a tumor suppressor (Janssens et al., 2005) through the activation of proapoptotic Bax (Xin and Deng, 2006), and dephosphorylation of Akt (Trotman et al., 2006), PP2A activity has also been shown to potently antagonize apoptosis, at least in certain model organisms (Li et al., 2002). Similarly, although increased PKA-I expression is observed in certain tumors (Tortora and Ciardiello, 2002), and its down-regulation by a cAMP analog (8-Cl-cAMP), has been associated with inhibition of tumor cell proliferation (Cho-Chung et al., 2002), other data have shown that PKA activity triggers apoptosis in tumor cells, via inactivating phosphorylation of Bcl-2 (Srivastava et al., 1998), or nuclear targeting the cell death effector Par-4 (Gurumurthy et al., 2005). Our findings suggest a context-specific paradigm for these signaling circuits, in which a proposed anti-tumorigenic activity of PP2A (Janssens et al., 2005) can be paradoxically subverted in transformed cells by dephosphorylating survivin on S20, thus heightening a IAP antiapoptotic threshold in tumors (Altieri, 2003; Wright and Duckett, 2005). Conversely, PKA phosphorylation of survivin on S20 may operate in context-specific tumor suppression by opposing IAP cytoprotection: a prediction consistent with the ability of non-PKA phosphorylatable survivin to accelerate tumor growth via ablation of apoptosis, in vivo.

Results from genetic models appear to support a physiological pro-apoptotic role of PKA relevant to endogenous tumor suppression. Mice with increased expression of PKA-RIα do not show increased incidence of tumors (Amieux and McKnight, 2002), and, conversely, antisense-based downregulation of PKA-RI in transgenic mice results in thyroid hyperplasia and adenomas, along with other mesenchymal tumors (Griffin et al., 2004). This phenotype closely mirrors a human condition, the Carney complex, in which inactivating mutations of PKA-RI are associated with multiple neoplasms and sporadic endocrine tumors (Kirschner et al., 2000).

In summary, we have identified a pathway of tumor cell apoptosis centered on differential PKA activity in specialized subcellular microdomains, and regulated intermolecular cooperation between IAPs. This regulatory circuitry could be exploited to maximize current strategies to disable IAP-mediated cell survival in cancer (Altieri, 2003; Wright and Duckett, 2005), and restore the sensitivity of tumor cells to apoptosis-inducing stimuli. In addition, lack of survivin phosphorylation on S20 in primary tumor specimens could provide a molecular biomarker for heightened apoptosis resistance in vivo, potentially indicative of poor response to therapy and unfavorable disease outcome.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Kinase assay

Various substrate proteins were incubated with the PKA catalytic subunit (Promega, 1.5 units/μl) in 40 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.2 mM ATP, 20 mM magnesium acetate, 1 mM dithiothreitol in the presence of 32P-γATP for 20 min at 30°C, as described (O'Connor et al., 2000). Phosphorylated proteins were detected by autoradiography. Alternatively, PKA kinase assays were carried out in the presence of unlabeled phosphate, and proteins were analyzed in pull down experiments with a S20-phospho-specific antibody, by Western blotting. The concentration of each target protein ranged between 100 to 600 ng in different experiments, with no differences in kinase activity observed for the various enzyme/substrate ratios. In some experiments, the phosphorylation reaction was terminated by adding 10 mM EDTA and 2 mM dithiothreitol. For Akt kinase assays, incubation reactions were prepared in the presence of recombinant activated Akt-1/PKBα (Upstate, 0.4 μg/μl), 8 mM MOPS/NaOH (pH 7.0), 0.2 mM EDTA, 10 mM magnesium acetate, and 0.1 mM ATP for 20 min at 30°C. Recombinant survivin was used at concentrations of 60-1200 ng, and recombinant Mdm2 was used as a control for Akt-dependent phosphorylation. In control experiments, the kinase was omitted from the reaction buffer.

PKA activity assay

Parental or stably transfected INS-1 cells expressing various survivin cDNAs were stimulated with 10 μM of the PKA activator, forskolin, harvested after 24 h, and analyzed for changes in survivin phosphorylation on S20 and modulation of PKA activity using a PKA Assay Kit (Upstate, NY). For these experiments, 50 μg of total cellular proteins were incubated in PKA assay buffer (20 mM MOPS pH 7.2, 25 mM β-glycerophosphate, 5 mM EGTA, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM dithiothreitol) with magnesium/ATP cocktail (75 mM magnesium chloride and 500 μM ATP), 1 mM kemptide and γ-32P-labeled ATP for 15 min at 30°C. After washing with 0.75% phosphoric acid and acetone, 25μl aliquots of the mixture were blotted on P81 paper, and assayed in a scintillation counter. In some experiments, INS-1 cells were treated with 40 μM of the PKA inhibitory peptide, PKI (Biomol), harvested after 48 h, and analyzed for changes in PKA activity or survivin phosphorylation on S20.

Cell death analysis

Parental or stably transfected INS-1 cells were treated with 0.1 μM staurosporing (STS) for 16 h, and analyzed for hypodiploid DNA content, by propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry, as described (Dohi et al., 2004a). Alternatively, STS-treated cells were simultaneously analyzed for caspase activity and propidium iodide staining by multiparametric flow cytometry using the CaspaTag caspase-3 activity kit (Intergen). Acute ablation of XIAP in INS-1 cells was carried out by siRNA using control or SMART Pool siRNA directed to rat XIAP (Dharmacon), and transfected using oligofectamine, as described (Beltrami et al., 2004). Modulation of XIAP expression in transfected cells was determined at increasing siRNA concentrations, by Western blotting.

Analysis of caspase activity

Caspase assays were performed by incubating recombinant procaspase-9 (4 nM) with recombinant survivin or various survivin mutants (30-300 nM), in the presence or absence of XIAP (10-1000 nM) for 15 min at 30°C. Incubation reactions were mixed with recombinant Apaf-1 (4 nM), cytochrome c (600 nM), dATP (200 μM) and procaspase-3 (4 nM), and caspase activity was determined continuously in the presence of 100 nM of Ac-DEVD-AMC (A.G. Scientific, Inc. CA) in buffer containing 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% CHAPS, 10% sucrose and 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.2. For synergistic experiments, a suboptimal concentration of XIAP (10 nM) producing ∼20% reduction in caspase-3 activity was used.

Xenograft tumor model

All experiments involving animals were approved by an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. For xenograft tumor formation, 1×106 stable INS-1 transfectants were injected (2 tumors/mouse, 8 tumors/group) into both flanks of 6-8 week old immunocompromised female CB17 SCID/beige mice (Taconic Farms). Tumor volume was measured in the three dimensions with a caliper at increasing time intervals after injection.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the unpaired t test on a GraphPad software package for Windows (Prism 4.0). A p value of 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Data include Supplemental Experimental Procedures and can be found with this article online at http://www.molecule.org/cgi/content/full.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. P. Fortugno for kinase assays with survivin peptides, S. Grossman for the Mdm2 cDNA, and S. Ghosh for the PKA-DN cDNA. This work was supported by NIH grants CA78810, CA90917 and HL54131.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abrams JM. Competition and compensation: coupled to death in development and cancer. Cell. 2002;110:403–406. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00904-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altieri DC. Validating survivin as a cancer therapeutic target. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:46–54. doi: 10.1038/nrc968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altieri DC. The case for survivin as a regulator of microtubule dynamics and cell-death decisions. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18:609–615. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaravadi R, Thompson CB. The survival kinases Akt and Pim as potential pharmacological targets. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2618–2624. doi: 10.1172/JCI26273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amieux PS, McKnight GS. The essential role of RI alpha in the maintenance of regulated PKA activity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;968:75–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldas H, Jiang Y, Holloway MP, Fangusaro J, Mahotka C, Conway EM, Altura RA. Survivin splice variants regulate the balance between proliferation and cell death. Oncogene. 2005;24:1994–2007. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho-Chung YS, Nesterova M, Becker KG, Srivastava R, Park YG, Lee YN, Cho YS, Kim MK, Neary C, Cheadle C. Dissecting the circuitry of protein kinase A and cAMP signaling in cancer genesis: antisense, microarray, gene overexpression, and transcription factor decoy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;968:22–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colnaghi R, Connell CM, Barrett RM, Wheatley SP. Separating the Anti-apoptotic and Mitotic Roles of Survivin. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:33450–33456. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600164200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cory S, Adams JM. The Bcl2 family: regulators of the cellular life-or-death switch. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:647–656. doi: 10.1038/nrc883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y, Ren X, Yang L, Lin Y, Wu X. A JNK-dependent pathway is required for TNFalpha-induced apoptosis. Cell. 2003;115:61–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00757-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohi T, Beltrami E, Wall NR, Plescia J, Altieri DC. Mitochondrial survivin inhibits apoptosis and promotes tumorigenesis. J Clin Invest. 2004a;114:1117–1127. doi: 10.1172/JCI22222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohi T, Okada K, Xia F, Wilford CE, Samuel T, Welsh K, Marusawa H, Zou H, Armstrong R, Matsuzawa S, et al. An IAP-IAP complex inhibits apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2004b;279:34087–34090. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400236200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckelman BP, Salvesen GS, Scott FL. Human inhibitor of apoptosis proteins: why XIAP is the black sheep of the family. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:988–994. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortugno P, Wall NR, Giodini A, O'Connor DS, Plescia J, Padgett KM, Tognin S, Marchisio PC, Altieri DC. Survivin exists in immunochemically distinct subcellular pools and is involved in spindle microtubule function. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:575–585. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.3.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold MG, Lygren B, Dokurno P, Hoshi N, McConnachie G, Tasken K, Carlson CR, Scott JD, Barford D. Molecular Basis of AKAP Specificity for PKA Regulatory Subunits. Mol Cell. 2006;24:383–395. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin KJ, Kirschner LS, Matyakhina L, Stergiopoulos S, Robinson-White A, Lenherr S, Weinberg FD, Claflin E, Meoli E, Cho-Chung YS, Stratakis CA. Down-regulation of regulatory subunit type 1A of protein kinase A leads to endocrine and other tumors. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8811–8815. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurumurthy S, Goswami A, Vasudevan KM, Rangnekar VM. Phosphorylation of Par-4 by protein kinase A is critical for apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:1146–1161. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.3.1146-1161.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada H, Becknell B, Wilm M, Mann M, Huang LJ, Taylor SS, Scott JD, Korsmeyer SJ. Phosphorylation and inactivation of BAD by mitochondria-anchored protein kinase A. Mol Cell. 1999;3:413–422. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80469-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie DG. The AMP-activated protein kinase pathway--new players upstream and downstream. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:5479–5487. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengartner MO. The biochemistry of apoptosis. Nature. 2000;407:770–776. doi: 10.1038/35037710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssens V, Goris J, Van Hoof C. PP2A: the expected tumor suppressor. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2005;15:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinderman FS, Kim C, von Daake S, Ma Y, Pham BQ, Spraggon G, Xuong NH, Jennings PA, Taylor SS. A Dynamic Mechanism for AKAP Binding to RII Isoforms of cAMP-Dependent Protein Kinase. Mol Cell. 2006;24:397–408. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschner LS, Carney JA, Pack SD, Taymans SE, Giatzakis C, Cho YS, Cho-Chung YS, Stratakis CA. Mutations of the gene encoding the protein kinase A type I-alpha regulatory subunit in patients with the Carney complex. Nat Genet. 2000;26:89–92. doi: 10.1038/79238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krammer PH. CD95's deadly mission in the immune system. Nature. 2000;407:789–795. doi: 10.1038/35037728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lens SM, Vader G, Medema RH. The case for Survivin as mitotic regulator. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18:616–622. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Scuderi A, Letsou A, Virshup DM. B56-associated protein phosphatase 2A is required for survival and protects from apoptosis in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:3674–3684. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.11.3674-3684.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marusawa H, Matsuzawa S, Welsh K, Zou H, Armstrong R, Tamm I, Reed JC. HBXIP functions as a cofactor of survivin in apoptosis suppression. Embo J. 2003;22:2729–2740. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer U, Charvet C, Wagman AS, Dejardin E, Green DR. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 regulates mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization and apoptosis by destabilization of MCL-1. Mol Cell. 2006;21:749–760. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor DS, Grossman D, Plescia J, Li F, Zhang H, Villa A, Tognin S, Marchisio PC, Altieri DC. Regulation of apoptosis at cell division by p34cdc2 phosphorylation of survivin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:13103–13107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.240390697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter AG. Protein translocation in apoptosis. Trends Cell Biol. 1999;9:394–401. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(99)01624-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed JC. Apoptosis-targeted therapies for cancer. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:17–22. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00241-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel T, Okada K, Hyer M, Welsh K, Zapata JM, Reed JC. cIAP1 Localizes to the nuclear compartment and modulates the cell cycle. Cancer Res. 2005;65:210–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y. A structural view of mitochondria-mediated apoptosis. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8:394–401. doi: 10.1038/87548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava RK, Srivastava AR, Korsmeyer SJ, Nesterova M, Cho-Chung YS, Longo DL. Involvement of microtubules in the regulation of Bcl2 phosphorylation and apoptosis through cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3509–3517. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.6.3509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SS, Yang J, Wu J, Haste NM, Radzio-Andzelm E, Anand G. PKA: a portrait of protein kinase dynamics. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1697:259–269. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2003.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortora G, Ciardiello F. Protein kinase A as target for novel integrated strategies of cancer therapy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;968:139–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trotman LC, Alimonti A, Scaglioni PP, Koutcher JA, Cordon-Cardo C, Pandolfi PP. Identification of a tumour suppressor network opposing nuclear Akt function. Nature. 2006;441:523–527. doi: 10.1038/nature04809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdecia MA, Huang H, Dutil E, Kaiser DA, Hunter T, Noel JP. Structure of the human anti-apoptotic protein survivin reveals a dimeric arrangement. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:602–608. doi: 10.1038/76838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virdee K, Parone PA, Tolkovsky AM. Phosphorylation of the pro-apoptotic protein BAD on serine 155, a novel site, contributes to cell survival. Curr Biol. 2000;10:R883. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00843-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong W, Scott JD. AKAP signalling complexes: focal points in space and time. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:959–970. doi: 10.1038/nrm1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright CW, Duckett CS. Reawakening the cellular death program in neoplasia through the therapeutic blockade of IAP function. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2673–2678. doi: 10.1172/JCI26251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin M, Deng X. Protein phosphatase 2A enhances the proapoptotic function of Bax through dephosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:18859–18867. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512543200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Data include Supplemental Experimental Procedures and can be found with this article online at http://www.molecule.org/cgi/content/full.