Abstract

Nongenomic estrogenic mechanisms offer an opportunity to explain the conundrum of environmental estrogen and plant estrogen effects on cells and animals at very the low concentrations which are prevalent in our environments and diets. Heretofore the actions of these compounds have not been adequately accounted for by laboratory tests utilizing assays for actions only via the genomic pathway of steroid action and the nuclear forms of estrogen receptor α and β. Membrane versions of these receptors, and the newly described GPR30 (7TMER) receptor protein provide explanations for the more potent actions of xenoestrogens. The effects of estrogens on many tissues demand a comprehensive assessment of the receptors, receptor levels, and mechanisms that might be involved, to determine which of these estrogen mimetic compounds are harmful and which might even be used therapeutically, depending upon the life stage at which we are exposed to them.

Keywords: environmental estrogen, phytoestrogen, membrane estrogen receptors, ERα, ERβ, GPR30, 7TMER

1. Introduction

Xenoestrogens are chemicals that mimic some structural parts of the physiological estrogen class of molecules, but are not endogenous to animals. These compounds may act as inappropriate estrogens, and/or could interfere with the actions of endogenous estrogens. Environmental estrogens are compounds that are by-products of manufacturing (certain plastics or detergents), or agricultural chemicals (such as some pesticides) that can disrupt or inappropriately mimic many estrogenic processes in animals (McLachlan 1993) (Singleton & Khan 2003). Xenoestrogens can also be synthesized by plants (such as isoflavones from soy, coumesterol from red clover), or fungi (such as zearalenone from grain molds), and can have endocrine-disrupting effects (Turcotte, Hunt, & Blaustein 2005) such as disruption of reproductive cycles when ingested. Alternatively, some phytoestrogens (e.g. soy isoflavones, resveratrol from red wine) have been suggested as safe replacement estrogens (Adlercreutz 1995), based on their consumption prevalence in certain cultures (eg. Asian diets contain lots of phytoestrogens, the French and Italians drink lots of red wine) correlating with fewer estrogen-provoked diseases (cancers) and fewer post-menopausal estrogen withdrawal symptoms (hot flashes, bone loss, cardiovascular events). The task at hand presently is to determine what, if any, biochemical effects are mediated by such compounds at typically encountered exposure doses, and whether xenoestrogens can be harmful or beneficial or both, depending upon the specific compound, tissue, and circumstances.

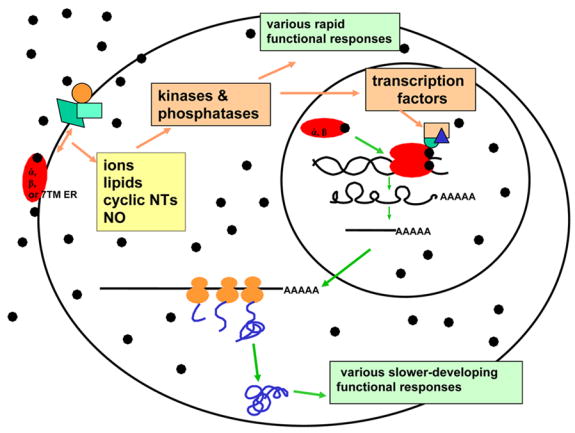

A long-time conundrum is that many of these xenoestrogens have been tested in cell and molecular laboratory assays for estrogenic action and deemed “weak (McLachlan 1993),” yet it is quite clear that there are measurable effects in animals (Brucker-Davis, Thayer, & Colborn 2001;Colborn, vom Saal, & Soto 1993) at the same doses. So how do we account mechanistically for all of these physiological effects? Perhaps by considering alternative mechanisms for the actions of steroids (genomic vs. membrane-initiated, see Fig. 1) and compounds which mimic them. In this review we will consider several important concepts about the activities of estrogens, both good and bad, among the plethora of estrogens to which humans and animals are exposed.

Figure 1.

The two major pathways of steroid action initiate in either the membrane (nongenomic) or the nucleus (genomic). Membrane-initiated nongenomic actions generally lead to rapid actions manifesting in a seconds-to-minutes timeframe, as they usually involve the enzymatic modification of premade signaling molecules and endproducts. They are known to be mediated by three known ERs, α, β, and GPR30 (7TMER) and are also attributed to various other membrane receptors. Genomic actions usually take hours to days to effect a change, as they rely on the synthesis and processing of a series of macromolecules, and are known to be mediated by ERs α and β. The two pathways may converge where kinases and phosphatases activated at the membrane go on to modify transcription factors that control gene expression. Diverse receptors and multiple interacting proteins at both the membrane and the nucleus (see unlabeled symbols in these locations) vary the responses in different the tissues and different circumstances. Only one ligand (●) is shown here, but when the many different estrogenic ligands are considered, another layer of response diversity is to be considered.

2. Tissues that respond to estrogens in either beneficial or harmful ways

Though we used to think of estrogen target tissues as mainly those with female reproductive functions, in the last decade or so we have discovered that practically every cell/tissue/organ system in the body responds to estrogens in some way. More sensitive methods now available detect low ER levels that explain some previously unexplained functional responses in both females and males [for example, (Audy, Vacher, & Dufy 1996;Castagnetta & Carruba 1995; Clarke C.H. et al. 2000; Fiorelli et al. 1996;Koldzic-Zivanovic et al. 2004;Kuiper et al. 1996;Lieberherr et al. 1993;Pappas et al. 1994;Simoncini et al. 2002;Thomas et al. 1993;Watson et al. 2006;Zaitsu et al. 2007)]. This expanded list of tissues with ER expression match quite nicely with human disease patterns that have long been known to differ between men and women, and between pre- and post-menopausal women (eg. heart disease, osteoporosis, colon cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, allergy and autoimmune diseases), and were therefore suspected to have something to do with the actions of estrogens. These functions of estrogens in tissues that are not strictly reproductive, are likely to be related to the need to engage many tissues in the preparation for pregnancy, including for example increased nutrient intake, mating and offspring-rearing behaviors, calcium mobilization for fetal bone growth, the need for increased circulatory system capacity, and protection of the fetus from immune attack. All of these tissues might either benefit from replacement estrogen actions, or be harmed by inappropriate estrogen actions.

3. Multiple ER subtypes, locations, and interactions

There are now multiple ER receptor subtypes to consider (α, β, or GPR30) and multiple subcellular locations for them (Filardo & Thomas 2005;Pappas, Gametchu, & Watson 1995b;Watson 2003;Watson, Alyea, Hawkins, Thomas, Cunningham, & Jakubas 2006;Watson & Gametchu 2003a). Collectively, these receptors inhabit nuclei and cytoplasm (Mangelsdorf et al. 1995), plasma membranes or perimembrane spaces (Clarke C.H., Norfleet, Clarke M.S.F., Watson, Cunningham K.A., & Thomas 2000;Thomas et al. 2005;Watson & Gametchu 2003b), and endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria (Evans, Jr. & Muldoon 1991;Filardo & Thomas 2005;Revankar et al. 2005;Yager & Chen 2007); they also sometimes change locations or arrangements within their locations, depending upon liganding or other circumstances (Campbell et al. 2002;Song et al. 2002). [Though they are other versions of ERs, the family of estrogen receptor-related (ERR) proteins are probably not potential targets because of their very small ligand binding pockets that can only accommodate ~4 carbon atoms (Kallen et al. 2004).] Steroid action, regardless of where in the cell it takes place, is likely to result from a very complex sequence of events that can assemble a different repertoire of proteins to function in different cell types, and under different circumstances. The job is unlikely to be carried out by a single protein making all response decisions. The existence of multiple types of steroid-binding proteins (receptors, enzymes, transporters, blood and cellular binding globulins and their receptors), and multiple examples of each type, contribute to the diversity of situations to which cells can respond. Though the exact roles of all of these protein types and their possible interactions with each other in a given pathway are still not clear, even in the comparatively well-studied genomic response mechanisms, it is likely that nuclear and membrane steroid receptors and the other unique steroid-binding membrane proteins all play a role in the sequence of events that together comprise a cell’s complete functional response to steroids. These different steroid-binding proteins can also have different affinities for various estrogens and xenoestrogens (Kuiper et al. 1998;Paech et al. 1997).

Systems biologists now inform us that many proteins simultaneously participate in cellular responses; structural biologists tell us that protein-protein interactions change the shape of proteins, and so may alter their ligand-binding characteristics, sometimes making them release their ligands. We are currently still limited in our understanding about the role of different membrane steroid receptor proteins because of our lack of knowledge about their distinct protein-protein interactions with each other or other classes of proteins. Knowledge of the consequences of these interactions, and the ligand repertoires that bind to and distinguish the different assemblages are incomplete. Other well known membrane receptors (eg. GABA, norepinephrine, dopamine, etc.) are often mentioned as candidates for alternative membrane steroid receptors (Majewska, Demirgören, & London 1990;Nadal et al. 2000a). These receptors might be mistaken for membrane steroid receptors because steroids appear to “compete” for the binding of their other primary ligands, when induced protein shape changes could be causing release of ligands. Experimental systems are often a mixture of components from a cell lysate or membrane preparation in which known steroid receptors could be included in low amounts (but not previously measured with insensitive methods) and the included steroid receptors might even physically interact with other membrane receptors. Other proteins may be misidentified as steroid receptors, based on their tight interactions with steroid receptors, thus conferring steroid-binding upon the complex. Therefore, some published studies may be misidentifying as “ERs” other membrane receptors based on their binding profiles, but these possibilities are still under investigation. We must now focus on the context of membrane-signaling steroid responses and begin to build knowledge of what constitutes a membrane-initiated steroid signaling complex.

A protein’s chemical environment (e.g. the lipid membrane vs. the aqueous nucleus and cytoplasm) can also change its conformation, and thereby its binding characteristics, further confusing the issue of pharmacological identification of receptors based purely on their ligand- or substrate-binding repertoires. The debate on the identity of membrane steroid receptors thus still rages on. I and others (Chen et al. 1999;Karas et al. 1999;Kousteni et al. 2001;Razandi et al. 1999) have identified a version of the “nuclear” ERα [using immunostaining (Pappas, Gametchu, & Watson 1995b), antisense knockdown studies (Norfleet et al. 1999), low vs. high levels of receptors correlating with responses (Bulayeva et al. 2005;Bulayeva, Gametchu, & Watson 2004a;Pappas, Gametchu, Yannariello-Brown, Collins, & Watson 1994;Pappas, Gametchu, & Watson 1995a;Watson, Pappas, & Gametchu 1995;Wozniak, Bulayeva, & Watson 2005b), antibody-induced or –blocked responses,(Norfleet et al. 2000) and the lack of GPR30 ER (Thomas, Pang, Filardo, & Dong 2005) or ERβ in cell lines (Bulayeva, Gametchu, & Watson 2004b;Campbell & Watson 2001)]. Others have built plausible stories about ERβ (Abraham et al. 2003;Ohshiro et al. 2006), GPR30 (Bologa et al. 2006;Filardo & Thomas 2005), and other proteins (Nadal et al. 2000b) mediating nongenomic estrogenic effects in their systems. Eventually we will probably discover subtle differences between regulation mediated by these different receptors and thus understand why different or multiple solutions are used in cells.

4. Cellular strategies for responding to steroids include several types of mechanisms/pathways

There are multiple mechanistic pathways to consider when deciding on the level of activity or potency of either physiological or nonphysiological estrogens (Mangelsdorf, Thummel, Beato, Herrlich, Schutz, Umesono, Blumberg, Kastner, Mark, Chambon, & Evans 1995;Watson & Gametchu 2003b). Until recently, most studies have focused on the genomic phase of steroid responses. These slow responses (hours to days) occur via a mechanism involving multiple syntheses and modifications to macromolecules, finally generating mature nucleic acid messengers and then proteins. These responses require investing substantial cellular resources to eventually remodel the cell’s protein repertoire (Hager 2001). However, rapid responses (seconds to minutes) usually initiate second messenger-triggered signal cascades which emanate from the plasma membrane. (A variation on rapid responses with intermediate time-scales can occur wherein the rapid activation of a molecule such as an enzyme may lead to the gradual build-up of response products). There are now examples of such initial rapid responses for almost every class of steroid and related compounds (Watson & Lange 2005), so it is increasingly clear that membrane-initiated steroid responses are a major alternative pathway of steroid action. We are now beginning to understand that steroid mimetics and steroid-targeted endocrine disruptors can also work via these rapid response pathways (Bulayeva & Watson 2004; onso-Magdalena et al. 2006;Wozniak, Bulayeva, & Watson 2005a). The broad tissue distribution of multiple subtypes of ERs working via these multiple mechanistic pathways provide a rich source of possible explanations about how xenoestrogens may mimic or disrupt estrogenic responses. Understanding these actions in detail will present promising and unique preventive and therapeutic opportunities.

5. Diversity via many “weak” vs. “strong” ligands, unconventional dose-response patterns, and tissue-specific responses

In the past, the basis for calling an estrogen “weak” or “strong” has been entirely dependent upon the nuclear transcription signaling mechanism (McLachlan et al. 1984). Initially this was determined by the ability of a single dose of an estrogen to drive ERα to the nucleus and keep it there (Lan & Katzenellenbogen 1976) (Anderson, Peck, Jr., & Clark 1975). However, now we have a new layer of considerations – via which cellular (genomic or nongenomic) pathway are various estrogens acting, and through which receptor protein subtype. It is just now becoming clear that “weak” activity via one pathway does not necessarily predict the potency of a hormone or mimetic acting via another signaling pathway. Though the activities of most environmental estrogens have been called “weak” for many years because of their inability to initiate nuclear retention and transcriptional effects, we now see that they are quite potent initiators of signal cascades emanating from the membrane. They cause these effects at concentrations that represent widespread and frequent low contamination levels (Bulayeva & Watson 2004;Wozniak, Bulayeva, & Watson 2005a). Since they also remain in the environment and within animal fat tissues for long periods of time, they are very serious threats to proper endocrine functioning. However, some xenoestrogen types such as phytoestrogens could also be serious contenders for safe effective therapeutic estrogen replacements via these alternative mechanisms.

How should we judge the potency of diverse estrogens? We now know that we must take into consideration multiple receptors and their tissue levels, their developmental expression patterns, and the different types of signaling generated (transcriptional vs. membrane-initiated second messengers and kinase cascades). However, in addition, we have recently recognized (but not yet understood) nonconventional dose-response patterns (called non-monotonic or bimodal) elicited b y steroid and mimetic compounds. These response patterns are characterized by stimulations of the response at low concentrations followed by inhibitions at high doses of hormone (biphasic, and described for many years), but where two such curves are put together. This creates a “camel back” response with two dose peaks of activity separated by doses of inactivity or inhibition. Such patterns are seen with both physiological and nonphysiological estrogens(Bulayeva, Wozniak, Lash, & Watson 2005;Bulayeva, Gametchu, & Watson 2004a;Bulayeva & Watson 2004;Wozniak, Bulayeva, & Watson 2005a). Many such patterns have more recently become evident due to improved, more highly controlled cell culture protocols in which endogenous steroids are more thoroughly removed from culture media; as a result previously undetected responses at the lowest concentrations (due to very low levels of steroids already present masking these responses) are thus revealed. These non-monotonic dose profiles unfortunately make it very difficult to predict toxic effects of environmental estrogens and therapeutic or toxic effects of phytoestrogens, which is usually done by extrapolating high-dose effects downward to predict threshold effects at low doses (Brucker-Davis, Thayer, & Colborn 2001). This just isn’t possible now that we recognize complex dose-responses which cannot predict effects from single or a few doses. This makes very difficult the job of government regulatory toxicologists trying to predict safe levels of contamination for environmental estrogens.

Most past studies have examined only very high (μM-mM) concentrations of xenoestrogens for activity (for example, (Li, Zhang, & Safe 2005)).Only recently have low concentrations been examined for nongenomic actions and found to be active (Bulayeva & Watson 2004;Nadal, Ropero, Laribi, Maillet, Fuentes, & Soria 2000a; onso-Magdalena et al. 2005; onso-Magdalena, Morimoto, Ripoll, Fuentes, & Nadal 2006;Singleton et al. 2003;Watson et al. 2005;Wozniak, Bulayeva, & Watson 2005b). Because organisms already have their own endogenous estrogens on board, it is also important to find out how exposures to low levels of xenoestrogens might interact with already present physiological hormone burdens. Will these combination responses be additive, synergistic or inhibitory? Xenoestrogens also elicit different temporal patterns of activation (Bulayeva & Watson 2004;Wozniak, Bulayeva, & Watson 2005a) and so may in fact be active in a different time frame than their co-stimulant (endogenous estrogens or other xenoestrogens). Thus the combination of responses could add up to a continual and sustained response, instead of an oscillating response (on and off) such as that seen in kinase activation studies with E2 and some xenoestrogens (Bulayeva, Gametchu, & Watson 2004a;Bulayeva & Watson 2004). In this way compounds that have different response “phasing” may represent a greater threat when present together. Another possibility for effects of xenoestrogen combinations, or combinations of xenoestrogens and physiological estrogens, could be overstimulation resulting in disruption. If different compounds acting via the same receptor are additive, they may eventually exceed the maximum effective dose, driving the steroid response to the inhibitory portion of the curve [for example (Kushner et al. 1990)]. This consideration is also pertinent to the important biological issue of exposures during different developmental/age/reproductive status windows in which different amounts of endogenous steroids are present. This may explain differing potential dangers of exposures during times when endogenous estrogen levels are particularly high or low in either males or females (infant, pubertal, reproductive, or post-reproductive stages). And all of these exposures may also interact with ingested phytoestrogens (such as soy isoflavones, coumestrol, or resveratrol), or therapeutic estrogen exposures (e.g. patches for hormone replacement or birth control). Altogether these estrogens could cause excessive estrogenic stimulation, which has also been shown to lead to cancer formation in some tissues (Ibarluzea et al. 2004;Lipsett 1977; Ravdin et al. 2007).

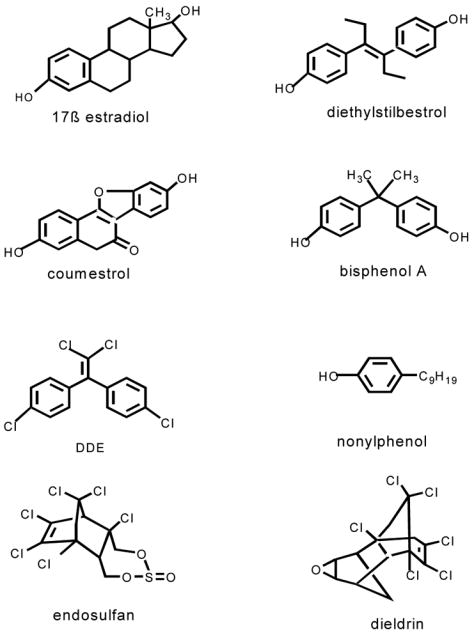

Prior data on diverse xenoestrogens did not point to simple ways to predict their activities and potencies based on structures, perhaps due to the wide diversity in the structures of the tested compounds (see Fig. 2 for examples compared to 17β-estradiol). The classical ERs α and β accept a wide diversity of lipophilic compounds as ligands. It has been suggested that this “binding promiscuity” may be due to their status as evolutionarily very primitive versions of ligand-activatable regulatory proteins that initially evolved to respond to a diverse set of molecules in the cell’s environment (Baker 2004). Because of this diversity of ligands, we will have to take each structural subclass separately and study them systematically to determine any structural rules for activity in genomic vs. nongenomic pathways.

Figure 2.

Structurally diverse xenoestrogens are shown in comparison to 17β-estradiol. Diethylstilbesterol is a pharmaceutical estrogen. Coumesterol is a plant estrogen from red clover and alfalfa sprouts. Bisphenol A and nonyphenol are byproducts of plastics manufacturing. DDE is the metabolite of DDT, and is a pesticide, as are endosulfan and dieldrin.

It is now accepted that nuclear versions of steroid receptors are affected by different tissue backgrounds, as membrane steroid receptors will likely also be as we study them further. This is because the functionally interacting repertoire of proteins (co-regulators in the case of transcription factors, and signaling partners in the case of the membrane steroid receptors) will be different in each cell type (Hermanson, Glass, & Rosenfeld 2002;Klinge 2001;Singleton, Feng, Burd, & Khan 2003). Each estrogen will have a different story in different tissues. These facts expand the complexities of understanding these responses, but also offer more opportunities to use diverse estrogens therapeutically in different tissues.

6. Summary: So many estrogens, so little time

Because of the documented functional changes or disruptions to animals, mechanistic explanations are needed for the actions of each xenoestrogen. Such knowledge will allow us to predict, prevent, and perhaps remediate their suspected effects on human and animal health. There is a need for studies of all potential xenoestrogens in detail, to fill in the matrix of what tissues they act in, and then what mechanistic pathways they use in those tissues to either disrupt or mimic hormone action. This is a giant task, but knowledge of tissue-specific effects might allow selective use of these compounds, much as SERMs (selective estrogen receptor modulators) are now being used selectively based on which vulnerable tissues are present in the patient (eg. women with or without a uterus) and on the therapeutic or preventive effect desired. Federal regulations about the allowable exposures for xenoestrogens must be based on sound data that takes into consideration all the mechanistic pathways via which these compounds mediate effects.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge grant support from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, the Sealy Memorial Foundation, the UTMB Center for Addiction Research, and the American Institute for Cancer Research. We also thank Dr. David Konkel for editorial advice.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abraham IM, Han SK, Todman MG, Korach KS, Herbison AE. Estrogen receptor beta mediates rapid estrogen actions on gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons in vivo. J Neurosci. 2003;23(13):5771–5777. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-13-05771.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adlercreutz H. Phytoestrogens: epidemiology and a possible role in cancer protection. [Review] Environmental Health Perspectives. 1995;103(Suppl 7):103–112. doi: 10.1289/ehp.95103s7103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JN, Peck EJ, Jr, Clark JH. Estrogen-induced uterine responses and growth: relationship to receptor estrogen binding by uterine nuclei. Endocrinology. 1975;96(1):160–167. doi: 10.1210/endo-96-1-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audy MC, Vacher P, Dufy B. 17-β-estradiol stimulates a rapid Ca2+ influx in LNCap human prostate cancer cells. Eur J Endocrinology. 1996;135(3):367–373. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1350367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker ME. Co-evolution of steroidogenic and steroid-inactivating enzymes and adrenal and sex steroid receptors. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2004;215(1–2):55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bologa CG, Revankar CM, Young SM, Edwards BS, Arterburn JB, Kiselyov AS, Parker MA, Tkachenko SE, Savchuck NP, Sklar LA, Oprea TI, Prossnitz ER. Virtual and biomolecular screening converge on a selective agonist for GPR30. Nat Chem Biol. 2006 doi: 10.1038/nchembio775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brucker-Davis F, Thayer K, Colborn T. Significant effects of mild endogenous hormonal changes in humans: Considerations for low-dose testing. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2001;109:21–26. doi: 10.1289/ehp.01109s121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulayeva NN, Gametchu B, Watson CS. Quantitative measurement of estrogen-induced ERK 1 and 2 activation via multiple membrane-initiated signaling pathways. Steroids. 2004b;69(3):181–192. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulayeva NN, Gametchu B, Watson CS. Quantitative measurement of estrogen-induced ERK 1 and 2 activation via multiple membrane-initiated signaling pathways. Steroids. 2004a;69(3):181–192. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulayeva NN, Watson CS. Xenoestrogen-induced ERK 1 and 2 activation via multiple membrane-initiated signaling pathways. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2004;112(15):1481–1487. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulayeva NN, Wozniak A, Lash LL, Watson CS. Mechanisms of membrane estrogen receptor-{alpha}-mediated rapid stimulation of Ca2+ levels and prolactin release in a pituitary cell line. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;288:E388–E397. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00349.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell CH, Bulayeva N, Brown DB, Gametchu B, Watson CS. Regulation of the membrane estrogen receptor-α: role of cell density, serum, cell passage number, and estradiol. FASEB Journal. 2002;16:1917–1927. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0182com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell CH, Watson CS. A comparison of membrane vs. intracellular estrogen receptor-α in GH3/B6 pituitary tumor cells using a quantitative plate immunoassay. Steroids. 2001;66:727–736. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(01)00106-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castagnetta LA, Carruba G. Human prostate cancer: a direct role for oestrogens. [Review] Ciba Foundation Symposium. 1995;191:269–86. doi: 10.1002/9780470514757.ch16. discussion 286–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Yuhanna IS, Galcheva-Gargova Z, Karas RH, Mendelsohn RE, Shaul PW. Estrogen receptor alpha mediates the nongenomic activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by estrogen. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1999;103(3):401–406. doi: 10.1172/JCI5347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke CH, Norfleet AM, Clarke MSF, Watson CS, Cunningham KA, Thomas ML. Peri-membrane localization of the estrogen receptor-α protein in neuronal processes of cultured hippocampal neurons. Neuroendocrinology. 2000;71:34–42. doi: 10.1159/000054518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colborn T, vom Saal FS, Soto AM. Developmental effects of endocrine-disrupting chemicals in wildlife and humans. Environmental Health Perspectives. 1993;101:378–384. doi: 10.1289/ehp.93101378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans AC, Jr, Muldoon TG. Characterization of estrogen-binding sites associated with the endoplasmic reticulum of rat uterus. Steroids. 1991;56(2):59–65. doi: 10.1016/0039-128x(91)90125-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filardo EJ, Thomas P. GPR30: a seven-transmembrane-spanning estrogen receptor that triggers EGF release. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2005;16(8):362–367. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorelli G, Gori F, Frediani U, Franceschelli F, Tanini A, Tostiguerra C, Benvenuti S, Gennari L, Becherini L, Brandi ML. Membrane binding sites and non-genomic effects of estrogen in cultured human pre-osteoclastic cells. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry & Molecular Biology. 1996;59(2):233–240. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(96)00092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hager GL. Understanding nuclear receptor function: from DNA to chromatin to the interphase nucleus. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2001;66:279–305. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(00)66032-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermanson O, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG. Nuclear receptor coregulators: multiple modes of modification. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2002;13(2):55–60. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(01)00527-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibarluzea JJ, Fernandez MF, Santa-Marina L, Olea-Serrano MF, Rivas AM, Aurrekoetxea JJ, Exposito J, Lorenzo M, Torne P, Villalobos M, Pedraza V, Sasco AJ, Olea N. Breast cancer risk and the combined effect of environmental estrogens. Cancer Causes Control. 2004;15(6):591–600. doi: 10.1023/B:CACO.0000036167.51236.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallen J, Schlaeppi JM, Bitsch F, Filipuzzi I, Schilb A, Riou V, Graham A, Strauss A, Geiser M, Fournier B. Evidence for ligand-independent transcriptional activation of the human estrogen-related receptor alpha (ERRalpha): crystal structure of ERRalpha ligand binding domain in complex with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor coactivator-1alpha. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(47):49330–49337. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407999200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karas RH, Hodgin JB, Kwoun M, Krege JH, Aronovitz M, Mackey W, Gustafsson JA, Korach KS, Smithi es O, Mendelsohn ME. Estrogen inhibits the vascular injury response in estrogen receptor beta-deficient female mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(26):15133–15136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinge CM. Estrogen receptor interaction with estrogen response elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29(14):2905–2919. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.14.2905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koldzic-Zivanovic N, Seitz PK, Watson CS, Cunningham KA, Thomas ML. Intracellular signaling involved in estrogen regulation of serotonin reuptake. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2004;226(1–2):33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2004.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kousteni S, Bellido T, Plotkin LI, O’Brien CA, Bodenner DL, Han L, Han K, DiGregorio GB, Katzenellenbogen JA, Katzenellenbogen BS, Roberson PK, Weinstein RS, Jilka RL, Manolagas SC. Nongenotropic, sex-nonspecific signaling through the estrogen or androgen receptors: Dissociation from transcriptional activity. Cell. 2001;104(5):719–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuiper GG, Enmark E, Pelto-Huikko M, Nilsson S, Gustafsson J-Å. Cloning of a novel estrogen receptor expressed in rat prostate and ovary. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 1996;93(12):5925–5930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuiper GG, Lemmen JG, Carlsson B, Corton JC, Safe SH, van der Saag PT, van der BB, Gustafsson JA. Interaction of estrogenic chemicals and phytoestrogens with estrogen receptor beta. Endocrinology. 1998;139(10):4252–4263. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.10.6216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner PJ, Hort E, Shine J, Baxter JD, Greene GL. Construction of cell lines that express high levels of the human estrogen receptor and are killed by estrogens. Molecular Endocrinology. 1990;4(10):1465–1473. doi: 10.1210/mend-4-10-1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan NC, Katzenellenbogen BS. Temporal relationships between hormone receptor binding and biological responses in the uterus: studies with short- and long-acting derivatives of estriol. Endocrinology. 1976;98(1):220–227. doi: 10.1210/endo-98-1-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Zhang S, Safe S. Activation of kinase pathways in MCF-7 cells by 17beta-estradiol and structurally diverse estrogenic compounds. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberherr M, Grosse B, Kachkache M, Balsan S. Cell signaling and estrogen in female rat osteoblasts: a possible involvement of unconventional nonnuclear receptors. J Bone & Min Res. 1993;8:1365–1376. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650081111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsett MB. Estrogen use and cancer risk. J Am Med Assoc. 1977;237(11):1112–1115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majewska MD, Demirgören S, London ED. Binding of pregnenolone sulfate to rat brain membranes suggests multiple sites of steroid action at the GABA-A receptor. Eur J Pharmacol Mol Pharmacol. 1990;189:307–315. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(90)90124-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangelsdorf DJ, Thummel C, Beato M, Herrlich P, Schutz G, Umesono K, Blumberg B, Kastner P, Mark M, Chambon P, Evans RM. The nuclear receptor superfamily - the second decade [Review] Cell. 1995;83(6):835–839. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90199-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan JA. Functional toxicology: A new approach to detect biologically active xenobiotics. Environmental Health Perspectives. 1993;101:386–387. doi: 10.1289/ehp.93101386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan JA, Korach KS, Newbold RR, Degen GH. Diethylstilbestrol and other estrogens in the environment. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1984;4(5):686–691. doi: 10.1016/0272-0590(84)90089-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadal A, Ropero AB, Laribi O, Maillet M, Fuentes E, Soria B. Nongenomic actions of estrogens and xenoestrogens by binding at a plasma membrane receptor unrelated to estrogen receptor alpha and estrogen receptor beta. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000b;97(21):11603–11608. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.21.11603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadal A, Ropero AB, Laribi O, Maillet M, Fuentes E, Soria B. Nongenomic actions of estrogens and xenoestrogens by binding at a plasma membrane receptor unrelated to estrogen receptor alpha and estrogen receptor beta. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000a;97(21):11603–11608. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.21.11603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norfleet AM, Clarke C, Gametchu B, Watson CS. Antibodies to the estrogen receptor-α modulate prolactin release from rat pituitary tumor cells through plasma membrane estrogen receptors. FASEB Journal. 2000;14:157–165. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.14.1.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norfleet AM, Thomas ML, Gametchu B, Watson CS. Estrogen receptor-α detected on the plasma membrane of aldehyde-fixed GH3/B6/F10 rat pituitary cells by enzyme-linked immunocytochemistry. Endocrinology. 1999;140(8):3805–3814. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.8.6936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohshiro K, Rayala SK, Williams MD, Kumar R, El-Naggar AK. Biological role of estrogen receptor beta in salivary gland adenocarcinoma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(20 Pt 1):5994–5999. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- onso-Magdalena P, Laribi O, Ropero AB, Fuentes E, Ripoll C, Soria B, Nadal A. Low doses of bisphenol A and diethylstilbestrol impair Ca2+ signals in pancreatic alpha-cells through a nonclassical membrane estrogen receptor within intact islets of Langerhans. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113(8):969–977. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- onso-Magdalena P, Morimoto S, Ripoll C, Fuentes E, Nadal A. The estrogenic effect of bisphenol A disrupts pancreatic beta-cell function in vivo and induces insulin resistance. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114(1):106–112. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paech K, Webb P, Kuiper GGJM, Nilsson S, Gustafsson J-Å, Kushner PJ, Scanlan TS. Differential ligand activation of estrogen receptors ERα and ERβ at AP1 sites. Science. 1997;227:1508–1510. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappas TC, Gametchu B, Watson CS. Membrane estrogen receptor-enriched GH3/B6 cells have an enhanced non-genomic response to estrogen. Endocrine. 1995a;3:743–749. doi: 10.1007/BF03000207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappas TC, Gametchu B, Watson CS. Membrane estrogen receptors identified by multiple antibody labeling and impeded-ligand binding. FASEB Journal. 1995b;9(5):404–410. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.5.7896011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappas TC, Gametchu B, Yannariello-Brown J, Collins TJ, Watson CS. Membrane estrogen receptors in GH3/B6 cells are associated with rapid estrogen-induced release of prolactin. Endocrine. 1994;2:813–822. [Google Scholar]

- Ravdin PM, Cronin KA, Howlader N, Berg CD, Chlebowski RT, Feuer EJ, Edwards BK, Berry DA. The decrease in breast-cancer incidence in 2003 in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(16):1670–1674. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr070105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razandi M, Pedram A, Greene GL, Levin ER. Cell membrane and nuclear estrogen receptors (ERs) originate from a single transcript: Studies of ERα and ERβ expressed in chinese hamster ovary cells. Molecular Endocrinology. 1999;13:307–319. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.2.0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revankar CM, Cimino DF, Sklar LA, Arterburn JB, Prossnitz ER. A transmembrane intracellular estrogen receptor mediates rapid cell signaling. Science. 2005;307(5715):1625–1630. doi: 10.1126/science.1106943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoncini T, Fornari L, Mannella P, Varone G, Caruso A, Liao JK, Genazzani AR. Novel non-transcriptional mechanisms for estrogen receptor signaling in the cardiovascular system. Interaction of estrogen receptor alpha with phosphatidylinositol 3-OH kinase. Steroids. 2002;67(12):935–939. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(02)00040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton DW, Feng Y, Burd CJ, Khan SA. Nongenomic activity and subsequent c-fos induction by estrogen receptor ligands are not sufficient to promote deoxyribonucleic acid synthesis in human endometrial adenocarcinoma cells. Endocrinology. 2003;144(1):121–128. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton DW, Khan SA. Xenoestrogen exposure and mechanisms of endocrine disruption. Front Biosci. 2003;8:s110–s118. doi: 10.2741/1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song RX, McPherson RA, Adam L, Bao Y, Shupnik M, Kumar R, Santen RJ. Linkage of rapid estrogen action to MAPK activation by ERalpha-Shc association and Shc pathway activation. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16(1):116–127. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.1.0748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas ML, Xu X, Norfleet AM, Watson CS. The presence of functional estrogen receptors in intestinal epithelial cells. Endocrinology. 1993;132:426–430. doi: 10.1210/endo.132.1.8419141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas P, Pang Y, Filardo EJ, Dong J. Identity of an estrogen membrane receptor coupled to a G protein in human breast cancer cells. Endocrinology. 2005;146(2):624–632. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turcotte JC, Hunt PJ, Blaustein JD. Estrogenic effects of zearalenone on the expression of progestin receptors and sexual behavior in female rats. Horm Behav. 2005;47(2):178–184. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson CS. The Identities of Membrane Steroid Receptorsand Other Proteins Mediating Nongenomic Steroid Action. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Boston: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Watson CS, Alyea RA, Hawkins BE, Thomas ML, Cunningham KA, Jakubas AA. Estradiol effects on the dopamine transporter - protein levels, subcellular location, and function. J Mol Signal. 2006;1:5. doi: 10.1186/1750-2187-1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson CS, Bulayeva NN, Wozniak AL, Finnerty CC. Signaling from the membrane via membrane estrogen receptor-alpha: estrogens, xenoestrogens, and phytoestrogens. Steroids. 2005;70(5–7):364–371. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson CS, Gametchu B. Proteins of multiple classes may participate in nongenomic steroid actions. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2003a;228(11):1272–1281. doi: 10.1177/153537020322801106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson CS, Gametchu B. Proteins of multiple classes participate in nongenomic steroid actions. Exp Biol Med. 2003b;228(11):1272–1281. doi: 10.1177/153537020322801106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson CS, Lange CA. Steadying the boat: integrating mechanisms of membrane and nuclear-steroid-receptor signalling. EMBO Rep. 2005;6(2):116–119. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson CS, Pappas TC, Gametchu B. The other estrogen receptor in the plasma membrane: implications for the actions of environmental estrogens. Environ Health Perspect. 1995;103(Suppl 7):41–50. doi: 10.1289/ehp.95103s741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak AL, Bulayeva NN, Watson CS. Xenoestrogens at picomolar to nanomolar concentrations trigger membrane estrogen receptor-alpha-mediated Ca2+ fluxes and prolactin release in GH3/B6 pituitary tumor cells. Environ Health Perspect. 2005a;113(4):431–439. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak AL, Bulayeva NN, Watson CS. Xenoestrogens at picomolar to nanomolar concentrations trigger membrane estrogen receptor-α-mediated Ca2+ fluxes and prolactin release in GH3/B6 pituitary tumor cells. Env Health Perspect. 2005b;113(4):431–439. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yager JD, Chen JQ. Mitochondrial estrogen receptors - new insights into specific functions. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2007;18(3):89–91. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaitsu M, Narita S, Lambert KC, Grady JJ, Estes DM, Curran EM, Brooks EG, Watson CS, Goldblum RM, Midoro-Horiuti T. Estradiol activates mast cells via a non-genomic estrogen receptor-alpha and calcium influx. Mol Immunol. 2007;44(8):1987–1995. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]