Summary

We report the 2.6-Å X-ray crystal structure of a 190-kDa homodimeric fragment from module 3 of the 6-deoxyerthronolide B synthase covalently bound to the inhibitor cerulenin. The structure shows two well-organized interdomain linker regions in addition to the full-length ketosynthase (KS) and acyltransferase (AT) domains. Analysis of the substrate-binding site of the KS domain suggests that a loop region at the homodimer interface influences KS substrate specificity. We also describe a model for the interaction of the catalytic domains with the acyl carrier protein (ACP) domain. The ACP is proposed to dock within a deep cleft between the KS and AT domains, with interactions that span both the KS homodimer and AT domain. In conjunction with other recent data, our results provide atomic resolution pictures of several catalytically relevant protein interactions in this remarkable family of modular megasynthases.

Introduction

Polyketide synthases (PKSs) are a large family of enzymes that catalyze the biosynthesis of structurally diverse and pharmacologically important natural products [1]. They assemble polyketide chains through repeated condensations between methylmalonyl or malonyl thioester building blocks and the growing polyketide acyl thioesters. Analogous to vertebrate fatty acid synthases, modular PKSs are large multi-enzyme assemblies that catalyze polyketide biosynthesis by an assembly line of active sites [2, 3]. In a typical PKS module there are minimally three domains; a catalytic ketosynthase (KS) and acyltransferase (AT) domain, and an acyl carrier protein (ACP). The AT domain transfers an extender unit from the corresponding malonyl- or methylmalonyl-CoA substrate to the phosphopantetheine arm of the ACP. Upon receiving the growing polyketide chain from the appropriate upstream module, the KS domain catalyzes decarboxylative condensation between the resultant acyl-KS intermediate and the respective malonyl- or methylmalonyl extender unit to form a β-ketoacyl-ACP. The core catalytic domains of a PKS module are flanked by catalytically inactive 20–300 amino acid linker regions whose structure and function are only beginning to be understood [4–6].

6-Deoxyerthronolide B synthase (DEBS), which produces the macrocyclic core of the antibiotic erythromycin, is comprised of three homodimeric polypeptides subunits, each of which consists of more than 3000 amino acids (Figure 1). Each DEBS polypeptide is made up of two polyketide chain elongation modules, with each module including all the required catalytic domains responsible for one round of polyketide chain extension and β-keto group modification. As the prototypical modular PKS, DEBS has been intensively investigated over the past two decades [7]. The modular nature of DEBS, together with the medicinal significance of its product, has also made it an attractive target for the production of novel polyketides by combinatorial biosynthesis [8, 9]. While some notable success in engineering DEBS to produce novel macrolides has been achieved, the majority of engineered PKSs have sub-optimal activity, arising at least in part from a lack of knowledge regarding precise domain boundaries [5, 10, 11]. Further progress in the engineering of the biosynthesis of novel polyketides requires detailed insights into the structure of DEBS and related modular PKSs.

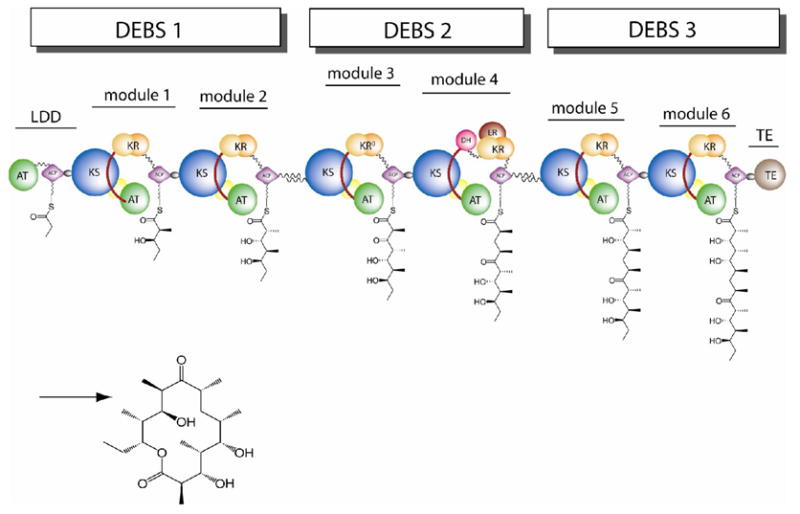

Figure 1.

Modular organization of 6-deoxyerythronolide B synthase (DEBS), illustrating the deduced topology. DEBS contains three large homodimeric polypetides, each of which consists of two modules. Each module is minimally composed of a core set of ketosynthase (KS), acyltranferase (AT) and acyl carrier protein (ACP) domains. Additional ketoreductase (KR), dehydratase (DH), and enoylreductase (ER) domains are responsible for processing of the β-ketoacyl-SACP intermediates, while a specialized thioesterase (TE) domain releases the mature heptaketide chain with cyclization to generate the 6-deoxyerythonolide B product.

We recently reported the 2.7-Å X-ray crystal structure of a 194-kDa homodimeric [KS][AT] fragment of DEBS module 5 [12]. In addition to the two pairs of catalytic KS and AT domains and the N-terminal docking domain, the structure also revealed two inter-domain linker regions with well defined three-dimensional structures that each show extensive interactions with the core catalytic domains. Although the overall primary sequences of these linker regions are less conserved compared to those of the corresponding catalytic domains, the amino acid residues responsible for specific domain-linker interactions are highly conserved in all six DEBS modules.

Here we present the 2.6-Å structure of a homologous [KS][AT] fragment from DEBS module 3. In addition to reconfirming the major architectural features of previously reported PKS modules and their constituent domains, the new structure, which includes a covalently bound molecule of the inhibitor cerulenin, provides a clearer definition of the KS active site. A detailed comparison between the active sites of DEBS KS3 and KS5 reveals a set of residues that are thought to control specificity for their respective triketide and pentaketide substrates. Lastly, guided by the recently solved NMR structure of the ACP domain of DEBS module 2, we have proposed a plausible KS-ACP docking model, that predicts both electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions at the critical domain-domain interface.

Results and Discussion

Catalytic activity of the crystallized fragment of DEBS module 3

Motivated by our earlier success with DEBS module 5, we initially prepared and attempted to crystallize the full-length [KS3][AT3] didomain protein with its intact N-terminal docking domain as well as the KS-to-AT and post-AT linkers. Unfortunately, no diffracting crystals could be obtained from this recombinant protein. Guided by encouraging preliminary data for a 190-kDa proteolytic fragment of this protein from which the N-terminal docking domain had been cleaved [13], we expressed the recombinant protein corresponding to this trypsin fragment and purified it to homogeneity. The KS acylation activity as well as the chain elongation properties of the purified protein were assayed, so as to assess the catalytic consequences of removing the N-terminal docking domain. Both activities were preserved in this truncated form of module 3, albeit at 30% the activity of the intact [KS][AT] didomain (data not shown). The recombinant truncated protein was therefore used for initial crystallization screens, which yielded needle crystals. Having established preliminary crystallization conditions, the truncated protein was then incubated with cerulenin, a known active-site directed irreversible inhibitor of the KS domains of numerous PKSs and fatty acid synthases, and the protein–cerulenin adduct was purified prior to protein crystallization. In a separate set of experiments, the recombinant protein was also incubated with (2S,3R)-2-methyl-3-hydroxypentanoyl-N-acetylcysteamine thioester and the resulting acylated protein purified for crystallization. Only the protein incubated with cerulenin gave diffractable crystals.

Overall Structure

The cerulenin-inhibited form of the 190 kDa fragment of DEBS module 3 was crystallized at room temperature by the hanging drop method. The protein crystallized in the space group P21 with one homodimer per asymmetric unit. The crystal structure was determined by molecular replacement using the recently determined structure of the [KS5][AT5] didomain from DEBS module 5 (PDBID: 2HG4) as the search model. The structure was refined to 2.6 Å resolution with R and Rfree values of 21.8% and 26.4%, respectively. The final protein model after refinement contained 869 out of the 896 residues of the subunit; no electron density was observed for two N-terminal residues, fourteen C-terminal residues, and eleven residues from two internal disordered regions. In each monomer, the cerulenin molecule was only partially defined by the electron density, suggesting that octadienyl moiety of the inhibitor that is distal to the point of attachment to the active site cysteine is relatively flexible and therefore disordered in the crystal. Data, refinement and model statistics are summarized in Table S1.

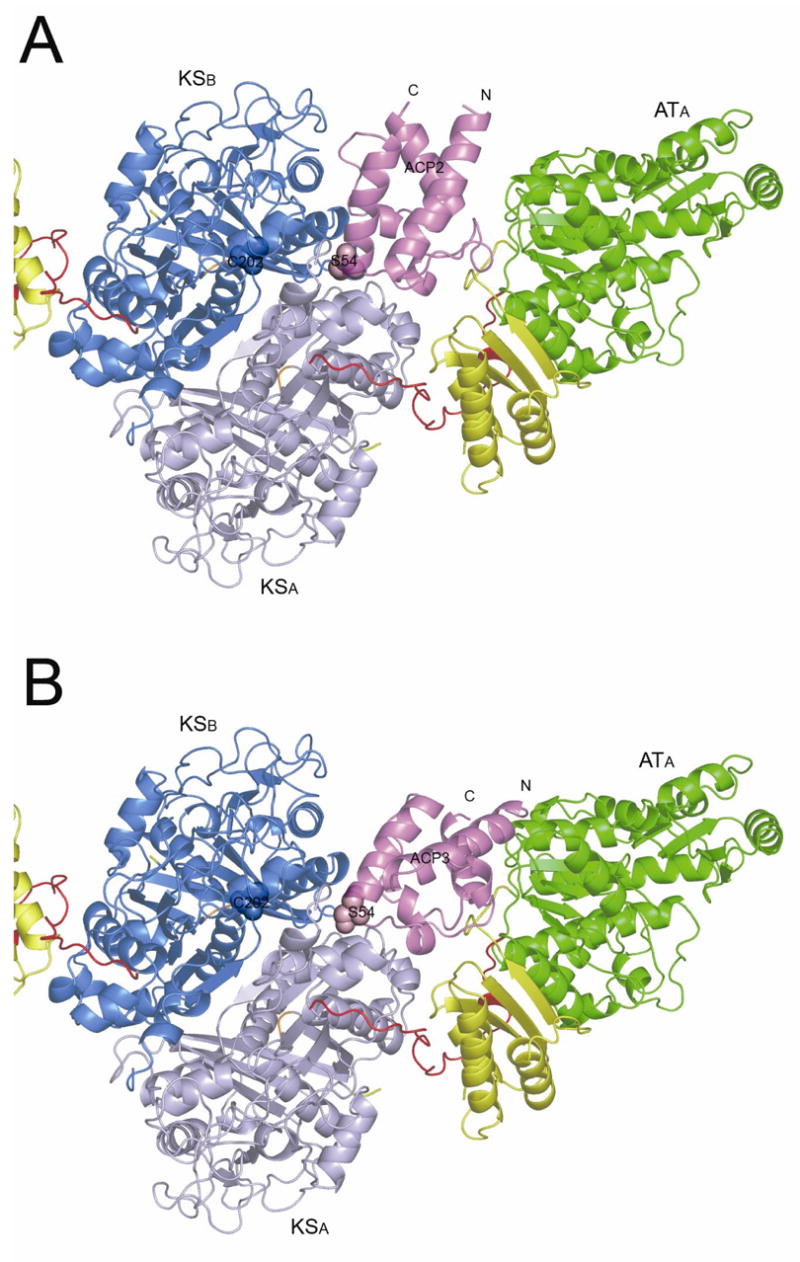

Notwithstanding the absence of the N-terminal docking domain, the overall organization of the truncated [KS3][AT3] didomain protein of DEBS module 3 is very similar to that of [KS5][AT5] protein from DEBS module 5 (Figure 2). The homodimeric [KS3][AT3] protein has two catalytic domains, KS3 and AT3, and two linker regions, the KS-to-AT linker and the post-AT linker. The dimer interface is located solely between the two KS domains. Similar to other condensing enzymes from fatty acid synthases and polyketide synthases, each KS3 domain adopts the five layered αβαβα fold, first observed in thiolase [12, 14–18]. The dimer interface is primarily comprised of two anti-parallel β-strands, one from each subunit, that are held together by backbone hydrogen bonds, thereby creating a ten-stranded β-sheet. The salt bridges previously observed at the KS5 dimer interface are not found in the corresponding KS3 dimer interface. Superposition of the Cα atoms of the KS3 and KS5 domains gives an r.m.s. deviation of 0.85 Å for 386 Cα atoms. A noticeable difference between the KS3 and KS5 domain is that KS3 has a longer loop corresponding to residues 71–91. Sequence alignment among the six DEBS KS domains shows that only KS5 is 12-residues shorter than other KS domains in this region, indicating that the remaining KS domains will have a loop of similar length to that of the KS3 domain.

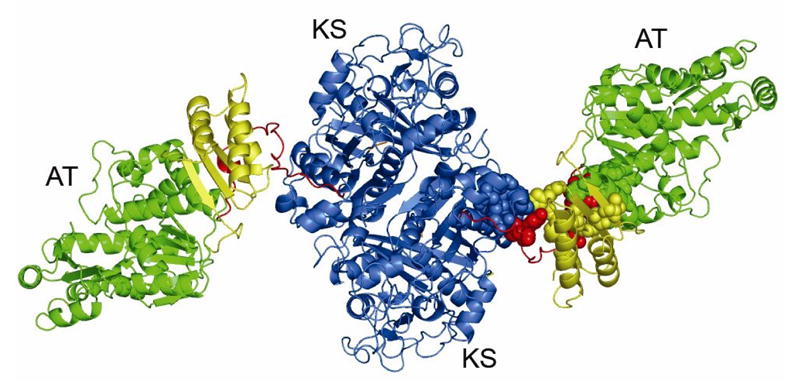

Figure 2.

X-ray crystal structure of [KS3][AT3] didomain of DEBS module 3. The protein forms a homodimer. The KS3 domain, KS3-to-AT3 linker, AT3 domain, and post-AT linker are shown in blue, yellow, green, and red, respectively. The conserved hydrophobic cores at the domain–linker interfaces of one monomer are shown as colored spheres.

The architecture of the AT3 domain is similar to that of the Escherichia coli and the Streptomyces coelicolor malonyl-CoA:ACP transferases, as well as the DEBS AT5 domain [12, 19, 20]. The AT3 domain has an α,β-hydrolase core and an appended smaller subdomain with a ferredoxin-like structure. The structures of the DEBS AT3 and AT5 domains can be superimposed with an r.m.s. deviation of 1.1 Å for 292 Cα atoms.

The ~100 residue-long KS-to-AT linker of the [KS3][AT3] protein is also structurally homologous to its [KS5][AT5] counterpart, with only a 1.54 Å r.m.s. deviation between the backbone atoms of the two KS-to-AT linkers, in spite of the fact that the overall sequence similarity (47%) between the two interdomain linkers is less than that between the corresponding pairs of KS and AT catalytic domains (~60%).. The KS3-to-AT3 linker contains a three-stranded parallel β-sheet, flanked by three α-helices on one side and two α-helices on the other. Similar to the KS5-to-AT5 linker, the three α-helices on one side are part of the KS3-to-AT3 linker itself, while the two α-helices on the other side are contributed by the AT3 domain and the post-AT linker, respectively. Finally, the post-AT linker wraps around both the AT3 domain and the KS-to-AT linker so as to engage in extensive contacts with the KS3 domain. The previously observed, highly conserved hydrophobic interactions between the two linkers and the two catalytic domains of [KS5][AT5] are also observed in the [KS3][AT3] protein. Specifically, the conserved residues Phe102, Phe106, Phe107, Val109, Ala114, Leu125, Trp129, Pro139, Met189, His516, Tyr898 and Phe900 comprise the hydrophobic core between the two linkers and the KS3 domain, while Pro473, Val475, Leu507, Ala510, Ala521, Val548, Trp637, Tyr640, Phe867, Leu868, Met871, Ala872, His875, Ile881, Trp883, and Leu887 form the hydrophobic core between the two linkers and the AT3 domain (Figure 2).

In the [KS5][AT5] protein, the N-terminal docking domains from the two monomers form an extended coiled-coil structure, contributing to the homodimer interface [12, 21]. The corresponding N-terminal residues involved in the coiled-coil interface are well conserved in the native DEBS module 3. It is therefore reasonable to expect that the N-terminal docking domain in the full length [KS3][AT3] protein also forms a similar coiled-coil structure. In the truncated [KS3][AT3] protein, the four residues, E27-L28-E29-S30 at the N-terminus belong to the original N-terminal docking domain of DEBS module 3. While no electron density was detected for the first two of these amino acids, the next two residues are visible in the [KS3][AT3] structure. As shown in Figure 3A, Glu29-Ser30-Asp31 at the N-terminus of KS3 do not overlap with the corresponding region of the [KS5][AT5] protein, in which the intact coiled-coil N-terminal docking domain is present (Figure 3A). Beyond this local difference, the excision of the N-terminal docking domain from KS3 has little apparent effect on the overall KS3 dimer geometry.

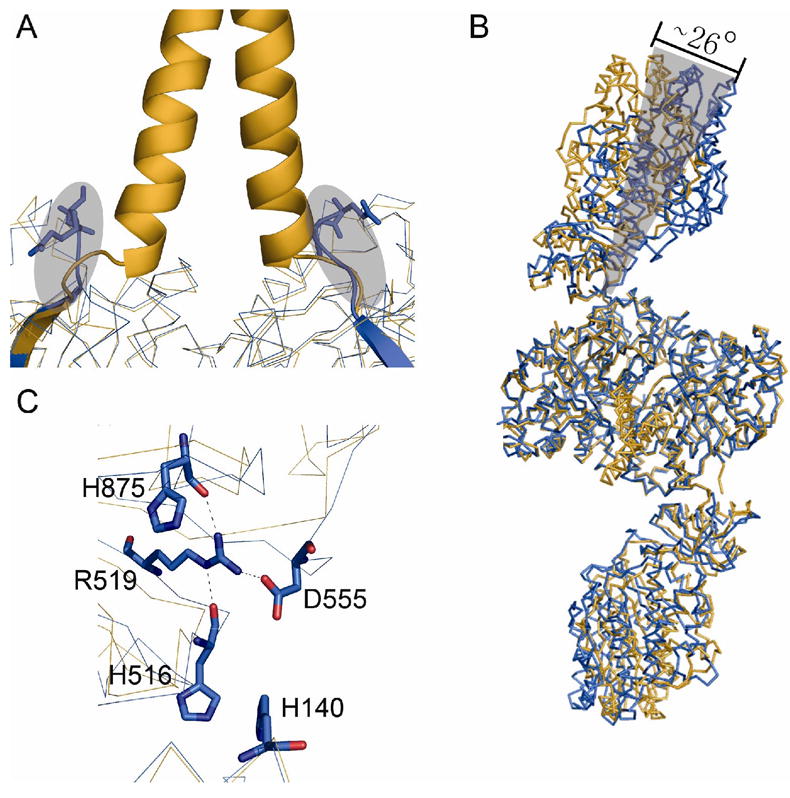

Figure 3.

Comparison of the structures of the [KS3][AT3] didomain (blue) and the [KS5][AT5] didomain (orange). (A) The coiled coil N-terminal docking domain of the [KS5][AT5] didomain is shown. The residues E29-S30 at the N-terminal of [KS3][AT3] are shown in sticks. The difference in the region of the N-terminal docking domains is depicted in the shadowed area. (B) Superposition of the complete backbones of the two didomains. The AT3 domain is rotated about 26° relative to the orientation of the AT5 domain. (C) Domain-domain interactions in the [KS3][AT3] didomain. Asp555 forms a salt bridge with Arg519; the latter residue also is hydrogen-bonded to His516 and H140.

Although the individual KS domain, KS-to-AT linker and AT domain structures are well conserved between the [KS3][AT3] and [KS5][AT5] proteins, a significantly higher net r.m.s. deviation of 4.2 Å is observed when the entire structures of both proteins are superimposed (Figure 3B). A close inspection of the superimposed structures shows that this divergence stems from a rotation of ~ 26° of the AT3 domain. As a result, the cleft between each AT3 domain and the KS3 dimer is smaller compared to its [KS5][AT5] counterpart. The origin of this relatively “closed” conformation of the [KS3][AT3] protein is unclear. It could be a crystallization artifact due to crystal packing; alternatively, the cleavage of the N-terminal docking domain may contribute to this “closed” conformation, since this truncated [KS3][AT3] only exhibits 30% of activity of the full-length protein. Nonetheless, this relatively “closed” conformation appears to be stabilized by a series of specific interactions, including hydrogen bonding and charge-charge interactions, that are absent in [KS5][AT5] (Figure 3C). For example, Asp555 forms a hydrogen bond with the side chain of Arg519, whose orientation is fixed by hydrogen bonding to the backbone carbonyl oxygens of both His516 and His875. In addition, Asp555 is also engaged in charge-charge interactions with side chains of both His140 and His516. None of the residues involved in the above interactions are conserved among the six DEBS KS domains, except Arg519 and His875.

The cerulenin binding site in KS3

Analogous to other fatty acid synthase and polyketide synthase condensing enzymes, the active site of the KS3 domain is buried, and therefore only accessible by the 18-Å phosphopantetheine arm of an ACP [12]. The active site Cys202 residue of KS3 resides in a nucleophilic elbow in a tight turn between a β-strand and an α-helix. His337 and His377, which form part of the catalytic triad, are located adjacent to Cys202. Besides providing an oxyanion hole to promote nucleophilic attack on the carbonyl of the acylthioester, these histidine residues have also been implicated in catalyzing decarboxylation of the co-substrate methylmalonyl-S-ACP [22, 23]. In the electron density map of the [KS3][AT3]-cerulenin complex, only the four-carbon hydrophilic head and attached groups of the cerulenin adduct are visible, albeit with a higher B factor than the rest of the protein (Figure 4A, 4B). The electron density corresponding to the hydrophobic octadienyl tail of the inhibitor is missing, presumably due to conformational disorder. A covalent bond is observed between C-2 of the cerulenin adduct and the active site Cys202. The carbonyl oxygen of the terminal carboxamide hydrogen bonds with the NE atoms of His337 and His377, while the carboxamide nitrogen is within hydrogen bonding distance of the backbone carbonyl oxygen of Phe442 and a water molecule. No other contacts are observed between the cerulenin adduct and the protein.

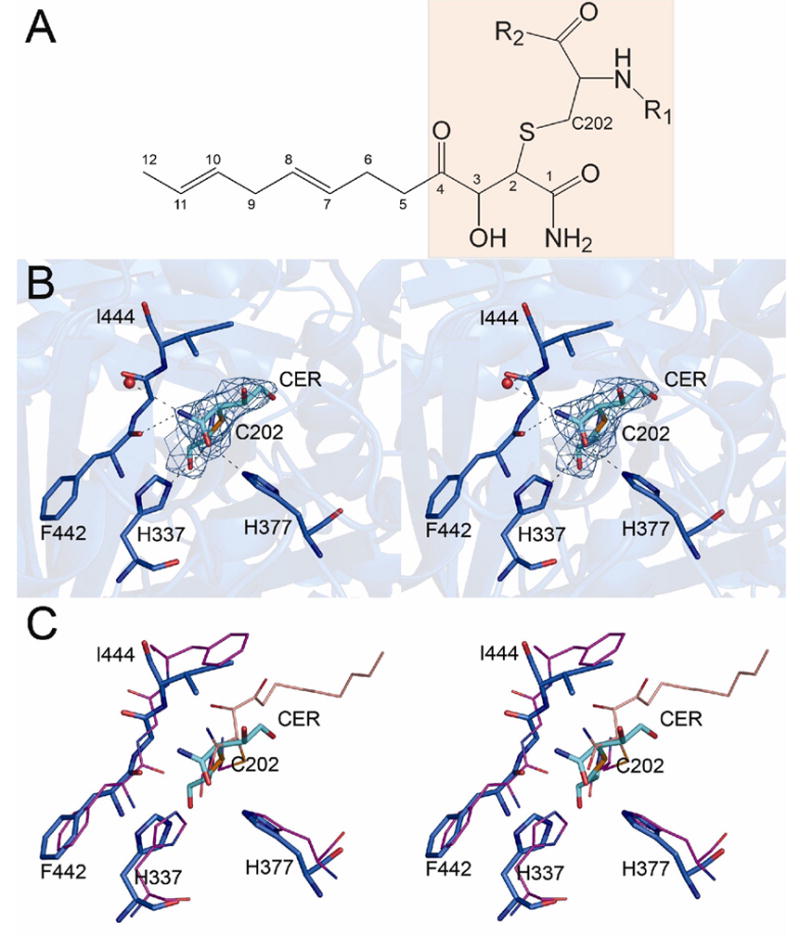

Figure 4.

The cerulenin binding site in the [KS3][AT3] didomain. (A) The cerulenin molecule is covalently bound to the enzyme; only the shaded portion is visible in the electron density map. (B) Stereoview of the final 2Fo−Fc map at the cerulenin (cyan) binding site contoured at 1.0 Å. (C) Stereoview of the structure of FabF-cerulenin complex (magenta) superimposed on the structure of the [KS3][AT3]-cerulenin didomain (blue).

To date, two crystal structures of KS-cerulenin complexes have been reported for β-ketoacyl-ACP:ACP synthases of type II fatty acid synthases, FabB-cerulenin and FabF-cerulenin [24, 25]. When the structure of cerulenin-bound [KS3][AT3] is superimposed on that of FabF-cerulenin, (Figure 4C), C-1 and C-2 of the covalently attached inhibitor occupy almost identical positions in the two proteins, while C-3 and C-4 are rotated more than 120° in the [KS3][AT3] complex relative to the FabF complex. This rotation may reflect the conformation of the flexible hydrophobic octadienyl tail of cerulenin in the [KS3][AT3] active site, since cerulenin has a lower binding affinity to KS domains from PKSs compared to those from fatty acid synthases [26].

Substrate Specificity of the KS domain: Comparing DEBS KS3 to KS5

DEBS KS3 and KS5 share 60% sequence identity but have different substrate specificities. The natural substrate of KS3 is a triketide, whereas the natural substrate of KS5 is a pentaketide (Figure 1). While KS3 can be stoichiometrically acylated by the N-acetylcysteamine thioester derivative of the natural diketide product of DEBS module 1, KS5 is acylated more slowly by this same analog under the same conditions. In contrast, KS5 accepts valeryl-SNAc as a substrate, but KS3 does not (Alice Chen, unpublished results).

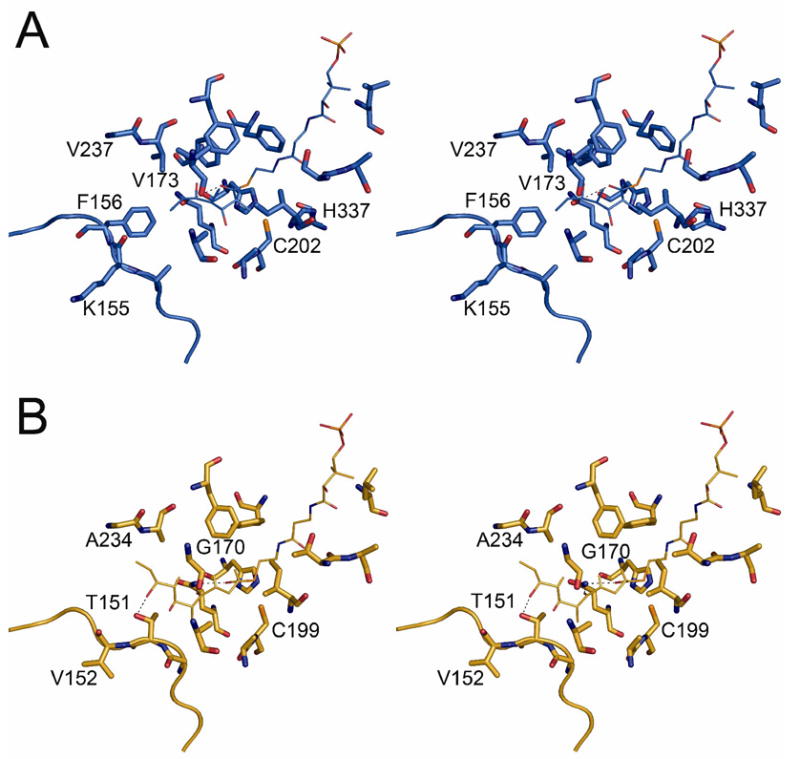

To better understand the structural basis for KS substrate specificity, we docked the natural triketide substrate of KS3, bound to a phosphopantetheinyl arm, into the substrate-binding pocket of KS3. This simulated complex was then superimposed onto the corresponding KS5-pentaketide complex that had been modeled earlier [12]. As shown in Figure 5, there are two major differences between the substrate-binding pockets of the KS3 and KS5 domains. First, a loop found at the dimer interface in both proteins (residues 153 – 158 in KS3 and 149 – 154 in KS5) has substantially different conformations in the otherwise very similar proteins. Compared to KS3, this loop is more extended in KS5. This difference in loop conformation results in the side chains of two KS3 residues (Lys155 and Phe156) being oriented in opposing directions compared to the corresponding KS5 residues, Thr151 and Val152. The orientation of Thr151 in KS5 is thought to be important for binding of its pentaketide substrate, based on a predicted hydrogen bond between the threonine side chain hydroxyl and the C-9 hydroxyl of the substrate. The counterpart Lys155 residue in KS3 points away from the substrate binding site. In addition, KS3 has more bulky residues in the active site than does KS5. For example, Phe156, Val173 and Val237 in KS3, which presumably interact with the untethered end of the polyketide chain, correspond to the smaller Val152, Gly170 and Ala234, respectively, in KS5. The resulting steric differences could influence the preferred substrate size that can be accommodated in the two different active sites.

Figure 5.

(A) Model of the triketide-phosphopantetheine group in the KS3 active site showing proposed interactions with residues lining the substrate-binding pocket. (B) Model of the pentaketide-phosphopantetheine group in the KS5 active site showing proposed interactions with residues lining the substrate-binding pocket.

It must be noted however, that neither substrate-binding pocket is especially crowded, and each may therefore readily undergo modest conformational adjustments upon substrate binding. Indeed, such conformational flexibility may be the origin of the observed relative substrate promiscuity of modular PKSs [27].

Interaction between the [KS][AT] homodimer and an ACP domain

During polyketide biosynthesis, the ACP domain interacts with several catalytic sites, in each case serving as a scaffold to which the malonyl- or methylmalonyl extender unit and the growing polyketide chain are alternately tethered. A number of recent studies have highlighted the critical importance of KS-ACP specificity, both during intermodular chain transfer as well as the intramodular KS-catalyzed decarboxylative condensation reactions [28–30]. Understanding the structural basis for this protein–protein specificity is of critical importance to the rational engineering of catalytically efficient PKSs.

In addition to knowledge of the [KS3][AT3] structure, computational prediction of the KS-ACP interface requires an accurate molecular model for the cognate ACP partner. Until recently, no structures were available for ACP domains derived from modular PKSs. Although the structures of more distantly related carrier proteins have been solved [31–38], their level of sequence identity with the DEBS ACP domains (<25%) is lower than the pairwise sequence identities between DEBS ACP domains (45–55%). We have recently solved the solution NMR structure of a recombinant ACP domain derived from DEBS module 2 and used this structure to derive homology models for the six remaining DEBS ACP domains, including ACP3 [39]. We have now utilized the solution NMR structure of ACP2 (the cognate partner of KS3 during inter-modular chain transfer) as well as the homology model of ACP3 (the cognate partner of KS3 during chain elongation) in computational docking studies in order to gain insight into the interface between the [KS3][AT3] protein and its partner ACP2 and ACP3 domains.

The 3D-dock [40] and Patchdock servers [41, 42] were used for individual computational docking simulations between both the ACP2 and ACP3 domains and the [KS3][AT3] protein. The two programs yielded similar docking results for both ACPs. As shown in Figure 6A and 6B, the most favorable ACP docking site, predicted based on a combination of binding energy and shape complementary, is the deep cleft between the KS3 and AT3 domains. The orientations of ACP2 and ACP3 predicted by the docking models are not identical; both the N-terminus and the C-terminus of ACP3 are relatively closer to the AT3 domain compared to ACP2. Nonetheless, the two docking models share important common features. Notably, while the ACPs are docked in the cleft of [KS3][AT3] subunit A, the active site residue Ser is actually positioned so as to direct its pantetheinyl prosthetic group and attached substrate to the active site of the KS domain of the paired subunit B. The validity of the calculated docking models is supported by three observations. First, the Ser54 residues of both ACP2 and ACP3, to which the 18 Å phosphopantetheinyl arms are covalently attached, are predicted to be positioned near the entrance of the substrate binding pocket of one KS3 monomer B, approximately 20 Å from the active site Cys202. Second, the docking model predicts that each ACP domain will interact with both subunits of the KS dimer. In a recently reported crystal structure of the yeast fatty acid synthase, the ACP was observed to preferentially bind to the KS domain, and to interact with both subunits of the KS dimer, but functional interaction was limited to one subunit of the KS dimer [43]. Although the overall architecture of the yeast fatty acid synthase is distinct from modular PKSs such as DEBS, it is likely that interaction between the core domain of yeast ACP and yeast KS domain is similar to that in modular PKSs. Third, the crystal structure of the yeast FAS also revealed that helix II of the core domain of ACP is important for KS recognition [43]. In the ACP docking model, the KS2-ACP2 and KS2-ACP3 interfaces both include helix II of each ACP. For example, Arg61 of helix II of ACP3 is predicted to form a hydrogen bond with Asn303 of KS3 while Leu55 from helix II of ACP2 is involved in hydrophobic interactions with KS3.

Figure 6.

Calculated docking model for the interaction between ACP domains and the [KS3][AT3] didomain. The ACP domains are shown as violet ribbons. The active site residues of the ACP and KS domains are shown as spheres. The [KS3][AT3] is shown in the same orientation as in Figure 2. (A) Model of ACP2 docked in the KS-AT cleft of the [KS3][AT3] didomain. (B) Model of ACP3 docked in the KS–AT cleft of the [KS3][AT3] didomain.

One interesting question arising from the docking model is, to which subunit of the homodimeric module does the docked ACP3 belong? Previous mutant complementation and crosslinking studies carried out in our lab have shown that the ACP from one subunit preferentially interacts with the KS domain from the opposite subunit [44]. In the ACP3 docking model, the C-terminal end of the post-AT linker from the [KS3][AT3] subunit A is indeed 16 Å closer to the N-terminus of the docked ACP3 domain than is the corresponding C-terminus of the post-AT linker belonging to the [KS3][AT3] subunit B. It is therefore tempting to conclude that the illustrated ACP3 should belong to subunit A of the homodimer (Figure 6B). This may be the case for those PKS modules that consist only of the three core KS, AT and ACP domains, in which the location of the ACP is constrained only by the length of AT-to-ACP linker. On the other hand, since the native DEBS module 3 also harbors an inactive KR domain (Figure 1), the position of the ACP domain is restrained not only by the KR-to-ACP linker, but also the KR domain itself. Since in the proposed structure model for the full DEBS module 3 [45], it is not yet possible to assign the individual KR domains to a given subunit, it is therefore premature to try to assign the docked ACP to a specific subunit of the homodimer pending the availability of an atomic resolution structure of the entire module.

An important feature of the ACP2 and ACP3 docking models is that both ACP domains are predicted to interact not only with both halves of the KS3 homodimer, but also with a considerable portion of the remainder of the [KS3][AT3] protein. In the discussion that follows, for brevity only the ACP3 docking model is analyzed in detail.

A total of 1628 Å2 surface area is predicted to be buried upon ACP3 binding, while the surface area buried between the KS3 homodimer and ACP3 is only 983 Å2. In fact, in a companion study carried out in our lab, we have shown that the efficiency of recognition of ACP3 by the KS3 domain is greatly enhanced by the presence of both the AT3 domain and the post-AT linker [46]. The interactions predicted to occur at the [KS3][AT3]:ACP3 interface are due to the contacts between ACP3 and the KS3 homodimer and the contacts between ACP3 and the rest of the [KS3][AT3] protein.

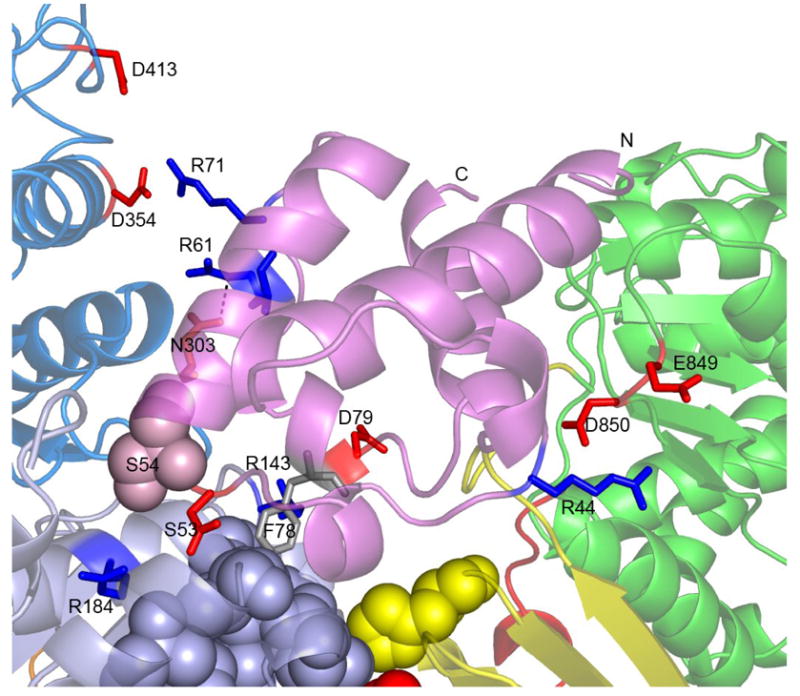

The interface between ACP3 and the KS3 homodimer involves both hydrophobic and hydrophilic interactions. For example, Phe78 of the ACP3 is predicted to bind in a hydrophobic KS3 core region (Figure 6C). As illustrated by the multiple sequence alignment (Figure S1), Phe78 of ACP3 is in fact strictly conserved in type I PKSs but not in type II PKSs. The same is true for the deduced hydrophobic cores in the corresponding Type I KS domains or Type II proteins (sequences not shown). In the NMR solution structure of ACP2 and the homology model of ACP3, Phe78 is located on the protein surface with its side chain pointing away from the protein. Interestingly, in the carrier protein domains (thiolation or T domains) of the enterobactin nonribosomal peptide synthetase, the residues that align with Phe78 of ACP3 have been shown to play a key role in mediating protein-protein interactions [47, 48]. In the latter system, mutation of Ala268 to Gln in the EntB-ArCP degraded interaction with EntF, leading to a 90-fold reduction in the rate of enterobactin production [47]. In like manner, mutation of the corresponding residue in the EntF-T domain abolished transfer of the acetyl group from the T to the thioesterase (TE) domain, indicating the crucial role of this residue in T-TE interaction [48]. Together, those observations reinforce the idea that Phe78 of ACP3 may be important for protein-protein interactions in DEBS KS3.

To investigate directly the role of Phe78 of the ACP3 domain, this residue was mutated to a charged Asp residue in order to disrupt the proposed hydrophobic interactions with the conserved hydrophobic core of the [KS][AT] didomain. Circular dichroism (CD) analysis confirmed the structural integrity of the F78D mutant relative to the wild-type ACP3 (Figure S2). The steady state kinetic parameters were determined for the F78D mutant by assaying the conversion of the diketide substrate, (2S, 3R)-2-methyl-3-hydroxypentanoyl-N-acetylcysteamine thioester, to the corresponding triketide ketolactone catalyzed by [KS3][AT3] [30]. The [KS3][AT3] protein was first incubated with the diketide to effect acylation and then [14C]methylmalonyl-CoA and ACP3 (WT or F78D) were added to the mixture. After incubation for an appropriate amount of time, the reaction was quenched and the derived triketide ketolactone was quantified (Figure S3 and Table S2). Mutation of F78D resulted in a modest decrease in efficiency of triketide lactone formation, as reflected in a 2-fold decrease in kcat as well as a 2-fold increase in KM, resulting in a net 4-fold reduction in catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) relative to the wild-type ACP3. These results suggest that Phe78 may contribute, but is not critical, to the interaction between ACP3 and [KS3][AT3].

The hydrophilic interactions at the KS3:ACP3 interface involve several charged residues. In addition to the hydrogen bond between Arg61 of ACP3 and Asn303 of KS3, Asp53 and Asp79 of ACP3 are likely involved in charge-charge interactions with Arg184 and Arg143 of KS3, respectively; these four residues are strictly conserved in all DEBS modules. Additional charge-charge interactions are predicted between Arg71 of ACP3 and Asp354 and Asp413 of KS3. None of these residues are conserved among other DEBS modules, suggesting that this electrostatic interaction may contribute to the observed KS:ACP recognition specificity [30].

The interaction at the interface of ACP3 and AT3 in the ACP3 docking model involves Arg44 of ACP3 and Glu849 and Asp850 of AT3. None of these three residues are conserved in the remaining five DEBS modules, suggesting that these charge-charge interactions may also contribute to the KS3:ACP3 specificity [30]. Since it is has been shown that KS3 and KS6 have orthogonal specificities toward ACP3 and ACP6, we wanted to test whether mutations around Arg44 of ACP3 could change the KS:ACP recognition specificity. Arg44 and Arg45 of ACP3 were therefore mutated to Asp and Gln, respectively, corresponding to the homologous residues of ACP6. Two single mutants R44D, R45Q and one double mutant R44D/R45Q were constructed. The CD spectra of the mutants showed characteristics of an α-helical conformation, suggesting equivalent tertiary structures of the mutants and wild-type ACP3 (Figure S2). The polyketide chain elongation assay was carried out using [KS3][AT3] or KS6][AT6] in combination with these three mutants. As shown in Figure S4, the two single mutants behaved similarly to the wild-type. Thus no triketide ketolactone formation was observed when the two single ACP3 mutants were incubated with [KS6][AT6]. In contrast, the double mutant totally lost the ability of the wild type to interact productively with [KS3][AT3], but instead showed about 6% of the activity of wild-type ACP6. Taken together, these experiments strongly suggest that specific hydrophilic interactions between ACP3 and KS3 involving Arg44 and Arg45 of ACP3 contribute to the observed KS3:ACP3 recognition specificity.

It should be stressed that functional interaction between ACP3 and the active site of the AT3 domain, from which the pantetheinyl group of ACP must acquire its methylmalonyl residue, cannot take place when ACP3 is bound as predicted into the cleft between the KS3 and AT3 domains. Similar to the [KS5][AT5] homodimer, the respective active site Cys and Ser residues of the KS3 and AT3 domains are separated by ~76 Å. A second, functionally distinct, ACP3:AT3 docking site must therefore be present on the face of the AT domain distal to the KS3–AT3 cleft. The latter interaction was not revealed, however, by the docking simulations.

Significance

Modular PKSs are responsible for the biosynthesis of polyketide natural products with a variety of antibiotic, antiviral, immunosuppressant, cholesterol-lowering, and anticancer activities. The modular organization of these PKSs makes them attractive targets for engineering designed to allow combinatorial biosynthesis of novel polyketide metabolites. Until now however, the lack of detailed structural and mechanistic information for these megaenyzmes, has greatly hampered progress in rational engineering of these modular polyketides, with primary sequence alignments being the only effective tool for predicting the boundaries of the constituent functional domains. The crystal structure of a 190-kDa homodimeric didomain fragment of DEBS module 3 with a covalently bound cerulenin at the KS3 active site provides important new insights into the structure and function of modular PKS proteins. The bound cerulenin also provides a more refined definition of both the KS3 and KS5 active sites. Detailed structural comparison between the structures of DEBS KS3 and KS5 highlight specific residues that may be important in determining both intrinsic substrate specificity and tolerance of the KS domains. Docking simulation using both the ACP2 NMR solution structure and an ACP3 homology model predicts that the ACP domain interacts with the KS domain by binding in the deep cleft between the KS and AT domains. Our results open the door to future efforts to engineer useful polyketide products with important medicinal activities.

Experimental Procedures

Reagents and Chemicals

DL-[2-Methyl-14C]-methylmalonyl-CoA was from American Radiolabeled Chemicals. (2S, 3R)-2-Methyl-3-hydroxypentanoyl-N-acetylcysteamine thioester was prepared was prepared by established methods [49–51]. All other chemicals were from Sigma. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plates were from J. T. Baker. SDS PAGE-gradient gels (4-15% acrylamide) were from BioRad. Ni-NTA affinity resin was from Qiagen. HiTrap-Q anion exchange column was from Amersham Pharmacia

Cloning, expression and purification of the [KS3][AT3] didomain of DEBS module 3

The construction of an expression vector encoding the [KS3][AT3] didomain from DEBS module 3 (pAYC02) has been previously described [30]. The N-terminal KS linker was deleted from the [KS3][AT3] didomain, using PCR to amplify pAYC02 from ELES to the natural AscI site, with introduction of an engineered NdeI site using primers 5′ – GCAGCGCCATATGGAGCTGGAATCCGACCCGATCG – 3′ and 5′ – GCGGCGCGCCGAGTCCGCTCGCC – 3′. The resulting NdeI-AscI fragment was cloned into back into NdeI-AscI-digested pAYC02 to yield plasmid pAYC09, encoding the DEBS [KS3][AT3] didomain lacking the N-terminal docking domain. The sequence of pAYC09 was verified directly by DNA sequencing and the plasmid was introduced into E. coli BL21(DE3) cells by electroporation. The resulting transformant was grown in LB medium at 37 °C to an OD600 of 0.6. The culture was then cooled to 18 °C, followed by induction with 0.2 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside, and grown for an additional 14 h at 18 °C. The cells were harvested by centrifugation (4,420×g for 15 min), resuspended in lysis/wash buffer (50 mM phosphate, pH 7.6, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole), and lysed by sonication (5 × 1 min). After the cell debris was removed, the supernatant was applied to a Nickel-NTA agarose (Qiagen) column in batch mode. After extensive washing with 10 column volumes of lysis/wash buffer, the protein was eluted with 3 column volumes of elution buffer (50 mM phosphate, pH 7.6, 100 mM NaCl, 150 mM imidazole). After determination of the protein concentration using Biorad assay, a 100-molar excess of the inhibitor cerulenin was added and the mixture was allowed to incubate overnight at 4°C to effect covalent modification. The resulting modified protein was further polished on a Hi-TrapQ anion exchange column (Amersham-Pharmacia) using a linear gradient of NaCl, with elution of the protein-inhibitor complex at approximately 350 mM NaCl. The purified complex was exchanged into 20 mM HEPES, buffer, pH 7.6, and concentrated to 1 mg/mL. The typical yield of KS-AT didomain-cerulenin complex was 20 mg/L of culture.

Crystallization and data collection for the [KS3][AT3] didomain of DEBS module 3 complexed with cerulenin

Crystals were grown at room temperature by using the hanging-drop vapor-diffusion method with a ratio of 2 μL [KS3][AT3]-cerulenin complex solution (1 mg/mL) to 2 μL of mother liquor. The well buffer contained 0.1 M HEPES pH 7.0, 0.2 M Li2SO4 and 25% PEG3350. The crystals belong to the space group P21 and contain two monomers per symmetric unit. The unit cell has dimensions of a = 75.203 Å, b = 139.005 Å, c = 102.342 Å, β = 106.14 °. For cryocooling, the crystals were harvested in a well solution with 10% glycerol. Diffraction datasets were collected on beamline 11-1 at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (SSRL) to 2.6 Å and processed using HKL2000 package [52]. The crystallographic data is summarized in Table S1.

The [KS3][AT3] protein acylated with (2S, 3R)-2-methyl-3-hydroxypentanoyl-N-acetylcysteamine thioester was also used in crystallization, but no diffractable crystals were obtained.

Structure Refinement and Model building

Initial phases were obtained by molecular replacement using the program Molrep in CCP4i [53] and thecoordinates of the DEBS module 5 [KS5][AT5] didomain (PDB ID: 2HG4) as the search model. The sequence was replaced by that of the [KS3][AT3] didomain from DEBS module 3, and the structure was further refined using CCP4i and then fit manually with O [54] and Coot [55]. Non-crystallographic symmetry restraints were applied for the initial rounds of refinement and removed for final stages. Both the 2Fo−Fc and Fo−Fc maps showed the presence of a portion of the bound cerulenin in the active site of the KS3 domain. The three dimensional structure of the relevant portions of the cerulenin adduct was then fit by hand into the visible electron density. Both sites in the asymmetric unit showed a good fit between the map and the hand-fit cerulenin molecules. Water molecules were added using Coot, followed by visual inspection with O at the final stage. Five percent of the reflections were excluded from refinement and constituted the Rfree set. The final geometry was assessed using PROCHECK [56]. Atomic coordinates of the [KS3][AT3] didomain from DEBS module 3 have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID code ZZZZ).

Molecular Docking Simulations

The homology model of the DEBS ACP3 domain was generated using the WHATIF homology model server [57] based on the solution NMR structure of the DEBS ACP2 domain (PDB ID XXXX) [38]. The calculated docking between ACP3 and the [KS3][AT3] didomain was carried out by using both the 3D-Dock program suite [40] and the Patchdock server [41, 42] (http://bioinfo3d.cs.tau.ac.il/PatchDock/index.html). When the 3D-Dock program suite was used, the coordinates of dimeric [KS3][AT3] didomain were defined as the static model, with ACP3 defined as the mobile model. The binding interface was exhaustively searched using default parameters. The resulting complexes were then scored by an empirical pair potential matrix [58] and the best scored complex was energy-minimized by CCP4i[53]. When the Patchdock server was used, the dimeric [KS3][AT3] didomain was defined as the receptor and the ACP3 protein was defined as the ligand. The best docking models returned by both programs were very similar, each identifying the deep cleft between the KS domain and the AT domain as the ACP3 docking site. The specific model that is discussed in detail in the text was calculated using the Patchdock server. The docking between ACP2 and the [KS3][AT3] was carried out in a similar manner.

Construction, expression and purification of ACP3 mutant F78D, R44D, R45Q, R44D/R45Q

Mutagenesis was performed with the QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene). Primer 5′-TCGCTGGTGGACGACCACCCCACCG-3′, 5′-CGCCGAGATCAACGTGGACC GCGCGTTCAGCG-3′, 5′-CGAGATCAACGTGCGCCAGGCGTTCAGCGAGCTC G-3′, and 5′-CGCCGAGATCAACGTGGACCAGGCGTTCAGCGAGCTCG-3′ and their complementary oligonucleotides were used to introduce the F78D, R44D, R45Q, and R44D/R45Q mutation(s) into DEBS ACP3. The expression and purification of the mutants were carried as described for wild type ACP3 [13, 30].

Triketide Ketolactone Formation

[KS3][AT3] didomain (2 μM for the F78D mutant time course and 10 μM for experiments with the R44D, R45Q, and R44D/R45Q mutants, in 100 mM phosphate, pH 7.2) was incubated with 5 mM (2S,3R)-2-methyl-3-hydroxypentanoyl-N-acetylcysteamine thioester and 5 mM TCEP for 1 h at room temperature to acylate KS3 to completion. HoloACP (four ACP concentrations ranging from 2 to 200 μM) and 200 μM DL-[2-methyl-14C]methylmalonyl-CoA were then added and allowed to react at room temperature. At various time-points, 10 μL of the reaction solution was drawn from the reaction mixture and quenched by adding 20 μL of 0.5 M potassium hydroxide. The mixture was further processed as described previously [30].

Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy

The proteins were diluted in 20 mM potassium phosphate at pH 7.2. All of the proteins had a concentration of 0.25 mg/ml; CD ellipticity was recorded using an Aviv 202-01 instrument (Aviv Associates, Lakewood, NJ). Spectra from 270 to 190 nm were scanned at a step of 1 nm at 25°C in a 0.1-cm cuvette, with three repeats and an averaging time of 1 sec.

Supplementary Material

Figure 7.

Close-up view of the ACP3 docking model. The residues involved in ACP–KS and ACP–AT charge-charge interactions are shown as sticks, and the KS and KS-to-AT linker residues involved in hydrophobic interactions with ACP3 are shown as grey and yellow spheres.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Irimpan I. Mathews for help with data collection and structure determination, Dr. Pavel Strop for helping with CD experiments, and Dr. Nathan A. Schnarr for helpful discussion and proofreading. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health Grants CA 66736 (to C.K.) and GM 22172 (to D.E.C.). Portions of this research were carried out at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory, a national user facility operated by Stanford University on behalf of the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Basic Energy Sciences.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.O’Hagan D. The Polyketide Metabolites. 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cane DE. Introduction: Polyketide and Nonribosomal Polypeptide Biosynthesis. From Collie to Coli. Chem Rev. 1997;97:2463–2464. doi: 10.1021/cr970097g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carreras CW, Khosla C. Purification and in vitro reconstitution of the essential protein components of an aromatic polyketide synthase. Biochemistry. 1998;37:2084–2088. doi: 10.1021/bi972919+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gokhale RS, Tsuji SY, Cane DE, Khosla C. Dissecting and exploiting intermodular communication in polyketide synthases. Science. 1999;284:482–485. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5413.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hans M, Hornung A, Dziarnowski A, Cane DE, Khosla C. Mechanistic analysis of acyl transferase domain exchange in polyketide synthase modules. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:5366–5374. doi: 10.1021/ja029539i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ranganathan A, Timoney M, Bycroft M, Cortes J, Thomas IP, Wilkinson B, Kellenberger L, Hanefeld U, Galloway IS, Staunton J, Leadlay PF. Knowledge-based design of bimodular and trimodular polyketide synthases based on domain and module swaps: a route to simple statin analogues. Chem Biol. 1999;6:731–741. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)80020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar P, Khosla C, Tang Y. Manipulation and analysis of polyketide synthases. Methods Enzymol. 2004;388:269–293. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)88023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cortes J, Haydock SF, Roberts GA, Bevitt DJ, Leadlay PF. An unusually large multifunctional polypeptide in the erythromycin-producing polyketide synthase of Saccharopolyspora erythraea. Nature. 1990;348:176–178. doi: 10.1038/348176a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donadio S, Staver MJ, McAlpine JB, Swanson SJ, Katz L. Modular organization of genes required for complex polyketide biosynthesis. Science. 1991;252:675–679. doi: 10.1126/science.2024119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McDaniel R, Kao CM, Hwang SJ, Khosla C. Engineered intermodular and intramodular polyketide synthase fusions. Chem Biol. 1997;4:667–674. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(97)90222-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruan X, Pereda A, Stassi DL, Zeidner D, Summers RG, Jackson M, Shivakumar A, Kakavas S, Staver MJ, Donadio S, Katz L. Acyltransferase domain substitutions in erythromycin polyketide synthase yield novel erythromycin derivatives. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6416–6425. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.20.6416-6425.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tang Y, Kim CY, Mathews II, Cane DE, Khosla C. The 2.7-Angstrom crystal structure of a 194-kDa homodimeric fragment of the 6-deoxyerythronolide B synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11124–11129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601924103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim CY, Alekseyev VY, Chen AY, Tang Y, Cane DE, Khosla C. Reconstituting modular activity from separated domains of 6-deoxyerythronolide B synthase. Biochemistry. 2004;43:13892–13898. doi: 10.1021/bi048418n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olsen JG, Kadziola A, von Wettstein-Knowles P, Siggaard-Andersen M, Lindquist Y, Larsen S. The X-ray crystal structure of beta-ketoacyl [acyl carrier protein] synthase I. FEBS Lett. 1999;460:46–52. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang W, Jia J, Edwards P, Dehesh K, Schneider G, Lindqvist Y. Crystal structure of beta-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase II from E.coli reveals the molecular architecture of condensing enzymes. Embo J. 1998;17:1183–1191. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.5.1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davies C, Heath RJ, White SW, Rock CO. The 1.8 A crystal structure and active-site architecture of beta-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase III (FabH) from escherichia coli. Structure. 2000;8:185–195. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00094-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pan H, Tsai S, Meadows ES, Miercke LJ, Keatinge-Clay AT, O’Connell J, Khosla C, Stroud RM. Crystal structure of the priming beta-ketosynthase from the R1128 polyketide biosynthetic pathway. Structure. 2002;10:1559–1568. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00889-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keatinge-Clay AT, Maltby DA, Medzihradszky KF, Khosla C, Stroud RM. An antibiotic factory caught in action. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:888–893. doi: 10.1038/nsmb808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keatinge-Clay AT, Shelat AA, Savage DF, Tsai SC, Miercke LJ, O’Connell JD, 3rd, Khosla C, Stroud RM. Catalysis, specificity, and ACP docking site of Streptomyces coelicolor malonyl-CoA:ACP transacylase. Structure. 2003;11:147–154. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(03)00004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Serre L, Verbree EC, Dauter Z, Stuitje AR, Derewenda ZS. The Escherichia coli malonyl-CoA:acyl carrier protein transacylase at 1.5-A resolution. Crystal structure of a fatty acid synthase component. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:12961–12964. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.12961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Broadhurst RW, Nietlispach D, Wheatcroft MP, Leadlay PF, Weissman KJ. The structure of docking domains in modular polyketide synthases. Chem Biol. 2003;10:723–731. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(03)00156-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.von Wettstein-Knowles P, Olsen JG, McGuire KA, Henriksen A. Fatty acid synthesis. Role of active site histidines and lysine in Cys-His-His-type beta-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthases. Febs J. 2006;273:695–710. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.05101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Witkowski A, Joshi AK, Smith S. Mechanism of the beta-ketoacyl synthase reaction catalyzed by the animal fatty acid synthase. Biochemistry. 2002;41:10877–10887. doi: 10.1021/bi0259047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Price AC, Choi KH, Heath RJ, Li Z, White SW, Rock CO. Inhibition of beta-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthases by thiolactomycin and cerulenin. Structure and mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:6551–6559. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007101200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moche M, Schneider G, Edwards P, Dehesh K, Lindqvist Y. Structure of the complex between the antibiotic cerulenin and its target, beta-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:6031–6034. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.10.6031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsukamoto N, Chuck JA, Luo G, Kao CM, Khosla C, Cane DE. 6-deoxyerythronolide B synthase 1 is specifically acylated by a diketide intermediate at the beta-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase domain of module 2. Biochemistry. 1996;35:15244–15248. doi: 10.1021/bi961972f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hunziker D, Wu N, Kenoshita K, Cane DE, Khosla C. Precursor directed biosynthesis of novel 6-deoxyerythronolide B analogs containing Non-natural Oxygen substituents and reactive functionalities. Tetrahedron Letters. 1999;40:635–638. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu N, Tsuji SY, Cane DE, Khosla C. Assessing the balance between protein-protein interactions and enzyme-substrate interactions in the channeling of intermediates between polyketide synthase modules. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:6465–6474. doi: 10.1021/ja010219t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu N, Cane DE, Khosla C. Quantitative analysis of the relative contributions of donor acyl carrier proteins, acceptor ketosynthases, and linker regions to intermodular transfer of intermediates in hybrid polyketide synthases. Biochemistry. 2002;41:5056–5066. doi: 10.1021/bi012086u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen AY, Schnarr NA, Kim CY, Cane DE, Khosla C. Extender unit and acyl carrier protein specificity of ketosynthase domains of the 6-deoxyerythronolide B synthase. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:3067–3074. doi: 10.1021/ja058093d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li Q, Khosla C, Puglisi JD, Liu CW. Solution structure and backbone dynamics of the holo form of the frenolicin acyl carrier protein. Biochemistry. 2003;42:4648–4657. doi: 10.1021/bi0274120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu GY, Tam A, Lin L, Hixon J, Fritz CC, Powers R. Solution structure of B. subtilis acyl carrier protein. Structure. 2001;9:277–287. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00586-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holak TA, Kearsley SK, Kim Y, Prestegard JH. Three-dimensional structure of acyl carrier protein determined by NMR pseudoenergy and distance geometry calculations. Biochemistry. 1988;27:6135–6142. doi: 10.1021/bi00416a046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharma AK, Sharma SK, Surolia A, Surolia N, Sarma SP. Solution structures of conformationally equilibrium forms of holo-acyl carrier protein (PfACP) from Plasmodium falciparum provides insight into the mechanism of activation of ACPs. Biochemistry. 2006;45:6904–6916. doi: 10.1021/bi060368u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crump MP, Crosby J, Dempsey CE, Parkinson JA, Murray M, Hopwood DA, Simpson TJ. Solution structure of the actinorhodin polyketide synthase acyl carrier protein from Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) Biochemistry. 1997;36:6000–6008. doi: 10.1021/bi970006+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Findlow SC, Winsor C, Simpson TJ, Crosby J, Crump MP. Solution structure and dynamics of oxytetracycline polyketide synthase acyl carrier protein from Streptomyces rimosus. Biochemistry. 2003;42:8423–8433. doi: 10.1021/bi0342259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong HC, Liu G, Zhang YM, Rock CO, Zheng J. The solution structure of acyl carrier protein from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:15874–15880. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112300200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Drake EJ, Nicolai DA, Gulick AM. Structure of the EntB multidomain nonribosomal peptide synthetase and functional analysis of its interaction with the EntE adenylation domain. Chem Biol. 2006;13:409–419. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alekseyev VY, Liu CW, Cane DE, Puglisi JD, Khosla C. Solution Structure and Proposed Domain-domain Recognition Interface of an Acyl Carrier Protein Domain from a Modular Polyketide Synthase. doi: 10.1110/ps.073011407. submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Katchalski-Katzir E, Shariv I, Eisenstein M, Friesem AA, Aflalo C, Vakser IA. Molecular surface recognition: determination of geometric fit between proteins and their ligands by correlation techniques. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:2195–2199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duhovny DNR, Wolfson HJ. Efficient Unbound Docking of Rigid Molecules. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 2002;2452:185–200. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schneidman-Duhovny D, Inbar Y, Polak V, Shatsky M, Halperin I, Benyamini H, Barzilai A, Dror O, Haspel N, Nussinov R, Wolfson HJ. Taking geometry to its edge: fast unbound rigid (and hinge-bent) docking. Proteins. 2003;52:107–112. doi: 10.1002/prot.10397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leibundgut M, Jenni S, Frick C, Ban N. Structural basis for substrate delivery by acyl carrier protein in the yeast fatty acid synthase. Science. 2007;316:288–290. doi: 10.1126/science.1138249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kao CM, Pieper R, Cane DE, Khosla C. Evidence for two catalytically independent clusters of active sites in a functional modular polyketide synthase. Biochemistry. 1996;35:12363–12368. doi: 10.1021/bi9616312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khosla C, Tang Y, Chen AY, Schnarr NA, Cane DE. Structure and Mechanism of the 6-Deoxyerythronolide B Synthase. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007 doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.053105.093515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen AY, Cane DE, Khosla C. Structure-Based Dissociation of a Type I Polyketide Synthase Module. Chem Biol. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.05.015. accepted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lai JR, Fischbach MA, Liu DR, Walsh CT. A protein interaction surface in nonribosomal peptide synthesis mapped by combinatorial mutagenesis and selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5314–5319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601038103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou Z, Lai JR, Walsh CT. Interdomain communication between the thiolation and thioesterase domains of EntF explored by combinatorial mutagenesis and selection. Chem Biol. 2006;13:869–879. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harris RC, Cutter AL, Weissman KJ, Hanefeld U, Timoney MC, Staunton J. Enantiospecific Synthesis of Analogs of the Diketide Intermediate of the Erythromycin Polyketide Synthase (PKS) J Chem Res. 1998;283:1230–1247. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jacobsen JR, Hutchinson CR, Cane DE, Khosla C. Precursor-directed biosynthesis of erythromycin analogs by an engineered polyketide synthase. Science. 1997;277:367–369. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5324.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cane DE, Kudo F, Kinoshita K, Khosla C. Precursor-directed biosynthesis: biochemical basis of the remarkable selectivity of the erythromycin polyketide synthase toward unsaturated triketides. Chem Biol. 2002;9:131–142. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Otwinowski ZMW. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Collaborative Computational Project N. Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–763. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jones TA, Zou JY, Cowan SW, Kjeldgaard Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr A . 1991;47(Pt 2):110–119. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Laskowski R, MacArthur M, Moss D, Thornton J. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Crystallogr. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rodriguez R, Chinea G, Lopez N, Pons T, Vriend G. Homology modeling, model and software evaluation: three related resources. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:523–528. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.6.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moont G, Gabb HA, Sternberg MJ. Use of pair potentials across protein interfaces in screening predicted docked complexes. Proteins. 1999;35:364–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.