Abstract

Lateral cilia of the gill of Mytilus edulis are controlled by a reciprocal serotonergic-dopaminergic innervation from their ganglia. Other bivalves have been studied to lesser degrees and lateral cilia of most respond to serotonin and dopamine when applied directly to the gill indicating a possible neuro or endocrine mechanism. Lateral cilia in Crassostrea virginica are affected by serotonin and dopamine, but little work has been done regarding ganglionic control of their cilia. We examined the role of the cerebral and visceral ganglia in innervating the lateral ciliated cells of the gill epithelium of C. virginica. Ciliary beating rates were measured in preparations which had the ipsilateral cerebral or visceral ganglia attached. Superfusion of the cerebral or visceral ganglia with serotonin increased ciliary beating rates which was antagonized by pretreating with methysergide. Superfusion with dopamine decreased beating rates and was antagonized by ergonovine. This study demonstrates there is a reciprocal serotonergic-dopaminergic innervation of the lateral ciliated cells, similar to that of M. edulis, originating in the cerebral and visceral ganglia of the animal and this preparation is a useful model to study regulatory mechanisms of ciliary activity as well as the pharmacology of drugs affecting biogenic amines in nervous systems.

Keywords: bivalves, cilia, Crassostrea virginica, dopamine, ganglia, gill, serotonin

1. Introduction

The gills of bivalve molluscs function in both a respiratory and a feeding role. Cilia are present on the gill filaments in the lateral, laterofrontal and frontal cells and each type have specific arrangements and functions. Lateral cilia serve a vital function by generating the water currents that allow gas exchange as well as regulate food intake and waste removal. Numerous studies indicate that the beating of the lateral cilia is under nervous or neurohormonal control in various bivalves.

Bivalve molluscs have a relatively simple bilaterally symmetrical nervous system composed of paired cerebral, visceral and pedal ganglia, and several pairs of nerves. The cerebral ganglia (CG) are connected to the visceral ganglia (VG) by a paired cerebrovisceral connective and the VG innervate each gill via branchial nerves. Most of the early work on nervous system control of lateral cilia in the gills of bivalves has been done on the blue mussel, Mytilus edulis, whose lateral cilia have long been known to be controlled by a reciprocal serotonergic-dopaminergic innervation from their ganglia (Catapane, et al., 1978, 1979). Serotonin (5-HT) and dopamine (DA), and the enzymes involved in their synthesis and degradation are present in the ganglia, branchial nerves and gill tissue of M. edulis (Blaschko and Milton, 1960; Welsh and Moorehead, 1960; Aiello and Guideri, 1966; Paparo and Finch, 1972, Stefano and Aiello, 1975; Stefano, et al., 1976, 1977a, Stefano, et al., b,c Catapane, 1982a). The CG and VG contain serotonergic and dopaminergic neurons (Stefano and Aiello, 1975; Stefano et al., 1976) that can be activated by either electrical stimulation or superfusion of the neurotransmitters directly to the ganglia. Serotonergic and dopaminergic nerve fibers are present within the branchial nerves and the branches that run beneath the gill lateral ciliated cells (Stefano and Aiello, 1975; Catapane, 1982a; reviewed by Aiello, 1990). Activation of serotonergic nerve fibers is cilio-excitatory while activation of dopaminergic fibers is cilio-inhibitory and these excitatory and inhibitory effects are blocked respectively by the serotonergic and dopaminergic antagonists methysergide (MS) and ergonovine (ERG) (Catapane et al., 1978, 1979; Catapane, 1983). In summary, a wealth of morphological pharmacology, neurobiochemical and physiological studies have shown 5-HT and DA act as peripheral and ganglionic neurotransmitters controlling lateral ciliary activity in the gill of M. edulis (Aiello and Guideri, 1964, 1965, 1966; Aiello, 1970; Stefano and Aiello, 1975; Catapane et al., 1978, 1978, 1980; Catapane, 1981, 1982a, b).

The regulation of neurotransmitter release and cell signaling mechanisms that control or modulate lateral cilia beating in the gill of M. edulis also has been studied. Opiate receptors and their endogenous effectors are believed to play a prominent role in the regulation of transmitter release in the molluscan nervous system. Opioid peptides and various narcotic agents increase DA concentrations in the ganglia of M. edulis in a naloxone sensitive manner (Stefano and Catapane, 1978, 1979) and potassium-stimulated DA release from the CG, VG and pedal ganglia can be inhibited by morphine and other related peptides (Stefano, et al., 1981). Morphine signaling in the nervous tissue of invertebrates involves the release of nitric oxide (Liu, et al., 1996) and both morphine and the cannabinoid anandamine inhibit the presynaptic release of DA in M. edulis via a nitric oxide-coupled mechanism (Stefano, et al., 1997). Opiate receptors are present in the VG and application of morphine to the VG inhibits DA release via a nitric oxide-dependent mechanism, enhancing lateral cilia beating by allowing 5-HT signals to prevail unimpeded (Cadet, 2004). Opiate signaling is not only localized to the ganglia of M. edulis but is present outside the central nervous system in the gill tissue (Manitone, et al., 2006). Topical application of morphine to isolated gill filaments inhibited spontaneous lateral cilia beating in a concentration dependent and naloxone reversible manner that was coupled to nitric oxide production (Manitone, et al., 2006). Morphine is present in the open circulatory system of bivalves (Stefano, et al., 2003) and can be endogenously produced from various precursors, including DA (Zhu, et al., 2005a,b). The fact that topical application of either DA or morphine to isolated gill tissue is cilio-inhibitory suggests that in the peripheral nervous system dopaminergic control of M. edulis ciliary beating may involve a morphine signaling element. Alternatively, endogenously produced opiates may work within the nervous system to modulate lateral cilia activity via an endocrine mechanism (Manitone, et al., 2006).

Less is known about the control of lateral cilia beating in the gills of other bivalves and to what extent the animal’s nervous and endocrine systems play in regulating this activity. When applied exogenously to isolated gills, 5-HT activates quiescent cilia (Aiello, 1960, 1970; Gosselin, 1961, 1966; Gosselin, et al., 1962; Aiello and Guideri, 1964, 1965, 1966) and in all bivalves studied stimulates metachronal lateral cilia beating in a dose dependent way (Gosselin, et al., 1962; Aiello, 1962, 1970, 1990, Aiello and Guideri, 1966; Paparo and Murphy, 1975; Jorgenson, 1976; Catapane, et al., 1978; Paparo, 1972, 1980; Sanderson and Satir, 1982; Sanderson, et al., 1985; Motokawa and Satir, 1975; Catapane, 1983, Gardiner et al., 1991, Gainey, et al., 1999a). As in M. edulis, serotonergic nerve fibers are present in the gill filaments of M. mercenaria (Gainey, et al., 2003) and the freshwater unionid mussel Ligumia subrostrara (Dietz et al., 1985).

The response to DA is less consistent. DA applied directly to gill tissue is cilio-inhibitory in M. edulis, Crassostrea virginica (Paparo and Aiello, 1970; Catapane, 1983; Paparo, 1985), Ostrea edulis, M. mercenaria and Modiolus modiolus (Gainey and Shumway, 1991). Dopaminergic fibers have been identified in the gill filaments of M. mercenaria, and the cilio-inhibitory effects of applied DA could be modulated by an SCP-like peptide endogenous to Mercenaria (Gainey, et al., 1999a). In contrast, topical application of DA had no effect on the lateral cilia of Geukensia demissa, formerly Modiolus demissus, (Catapane, 1983), Argopecten irradians and Mya arenaria (Gainey and Shumway, 1991); and was reported to stimulate the beating of lateral cilia in the fresh water unionid mussel L. subrostrata (Gardiner, et al., 1991). Furthermore, while electrical stimulation to the branchial nerve or cerebrovisceral connective alters lateral ciliary activity in the gill of M. edulis, it has no effect on this activity in G. demissa, indicating that what we know about nervous system control of the lateral cilia from M. edulis may not be directly applicable to all bivalves (Catapane, 1983).

The lateral cilia in the gill of the Eastern oyster C. virginica are affected by 5-HT and DA but little work has been done with respect to determining if lateral ciliary activity is controlled by a neuro or endocrine mechanism (Gosselin, et al., 1962; Paparo, 1986a,b). In this study we examined the role of the CV and VG in the innervation and control of the lateral cilia in gill of C. virginica.

2. Materials and Methods

5-HT, DA, MS, a 5-HT antagonist, and ERG, a DA antagonist, were obtained from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Just prior to use, drugs were dissolved in artificial sea water (ASW, Instant Ocean Aquarium Systems) or ASW containing 10 mg% ascorbic acid buffered with sodium bicarbonate, pH 7.0, to retard DA oxidation as described by Malanga (1975).

Adult C. virginica of approximately 80 mm shell length were obtained from Frank M. Flower and Sons Oyster Farm in Oyster Bay, NY, USA. They were maintained in the lab for up to two weeks in temperature regulated aquaria in ASW at 16 – 18°C, specific gravity of 1.024 ± 0.001 and pH of 7.2 ± 0.2. Each animal was tested for health prior to experimentation by the resistance it offered to being opened. Animals which fully closed in response to tactile stimulation and required at least moderate hand pressure to being opened were used for the experiments. Specimens were prepared for microscopic observation of ciliary beating of the lateral ciliated cells of the gill epithelium by removing the shells, mantle and most of the internal organs from the gills and ganglia. CG preparations were prepared by dissecting the animals so that the gill with the ipsilateral branchial nerve, VG, cerebrovisceral connective and CG attached were positioned in a special observation chamber containing ASW. VG preparations were prepared similarly except that the ipsilateral CG also was excised. The observation chambers had a Plexiglass barrier separating the CG (CG preparations) or VG (VG preparations) from the gill so that neurotransmitters/antagonists could be specifically applied to either ganglion or gill without leakage of the chemical to the other chambers (Catapane, et al., 1978). Gills were positioned so that the cilia of the medial gill lamina were viewed at 100200X magnification with an Olympus CK inverted microscope with transmitted stroboscopic light from a Grass Instruments PS 22 Photo Stimulator. Lateral ciliary activity was measured by the method of Catapane, et al., (1978) by synchronizing the flashing rate of the stroboscope with the beating rate of the cilia. Because the lateral cilia beat in a metachronal wave pattern (Aiello and Sleigh, 1972) when synchronization is achieved the lateral cilial waves appear motionless in a characteristic horseshoe like configuration. At all multiple synchronizing rates above the one corresponding to the true beating frequency, the ciliary wavelength will appear to be a fraction of the true wavelength. Ciliary beating rates are expressed as beats/s ± SEM. A one-tailed Student t test was used for statistical analysis.

3. Observations and Results

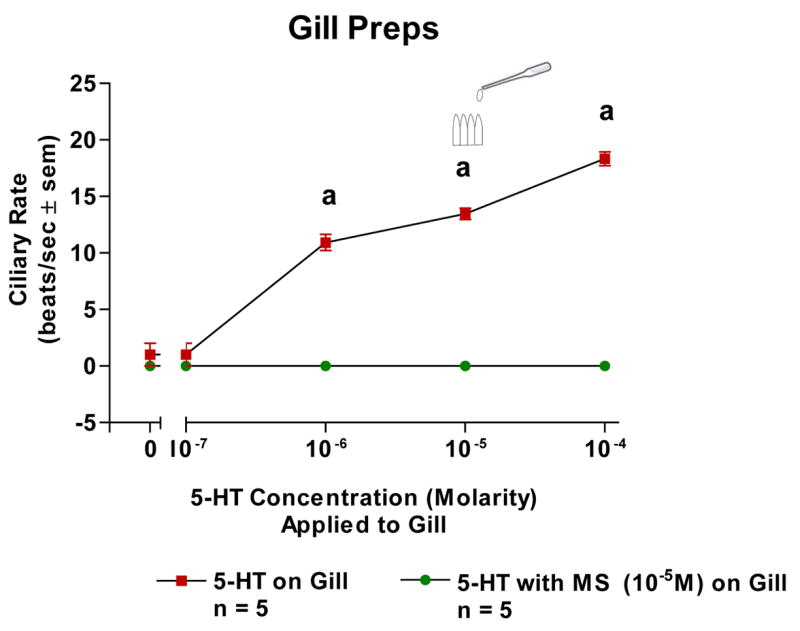

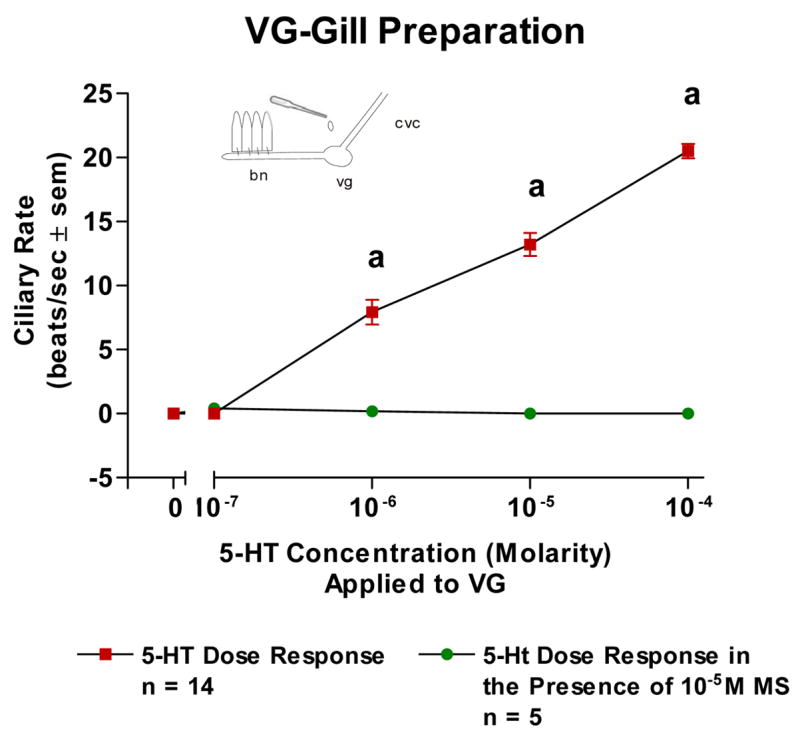

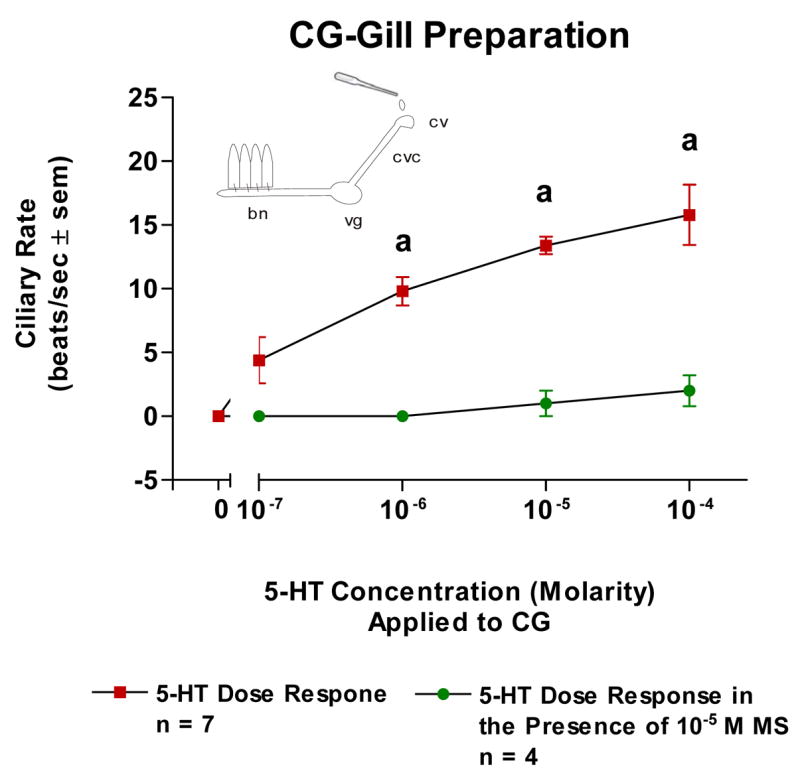

The basal beating rate of the lateral cilia of the ciliated cells of oyster gill epithelium tended to be quiescent after preparing and positioning the specimens in the chambers for microscopic observations. Adding 5-HT (10−7–10−4 M) directly to isolated gill filaments activated the lateral cilia and produced a dose dependent increase in ciliary beating rates and this was blocked by pretreating the gill with 10−5 M MS (Figure 1). Superfusion of the VG of VG preparations with 5-HT produced a dose dependent increase in beating rates which was antagonized by pretreating the VG with 10−5 M MS (Figure 2). Similarly, 5-HT increased beating rates when applied to the CG of CG preparations and this was antagonized by pretreating the CG with 10−5 M MS (Figure 3).

Fig. 1.

The changes in beating rates (beats/s ± SEM) of lateral cilia in response to serotonin applied directly to excised gill with and without MS (10−5M). Statistical analysis was determined by student’s t-test. ap < 0.01. N = 5 for each set.

Fig. 2.

The changes in beating rates (beats/s ± SEM) of lateral cilia in response to superfusion of serotonin to the visceral ganglia of VG Preparations with and without methysergide added to the VG. Statistical analysis was determined by t-test. ap < 0.01.

Fig. 3.

The changes in beating rates (beats/s ± SEM) of lateral cilia in response to superfusion of serotonin to the cerebral ganglia of CG Preparations with and without methysergide added to the CG. Statistical analysis was determined by a t-test. ap < 0.01.

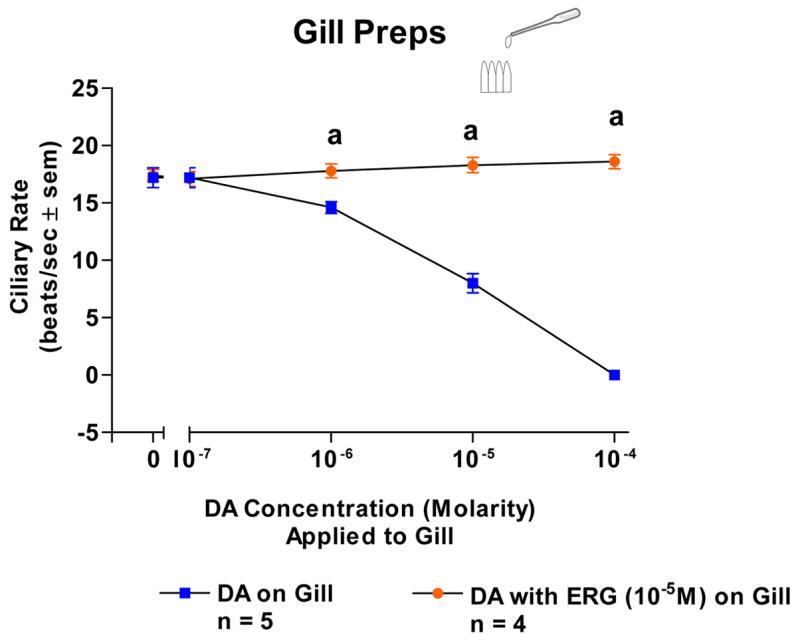

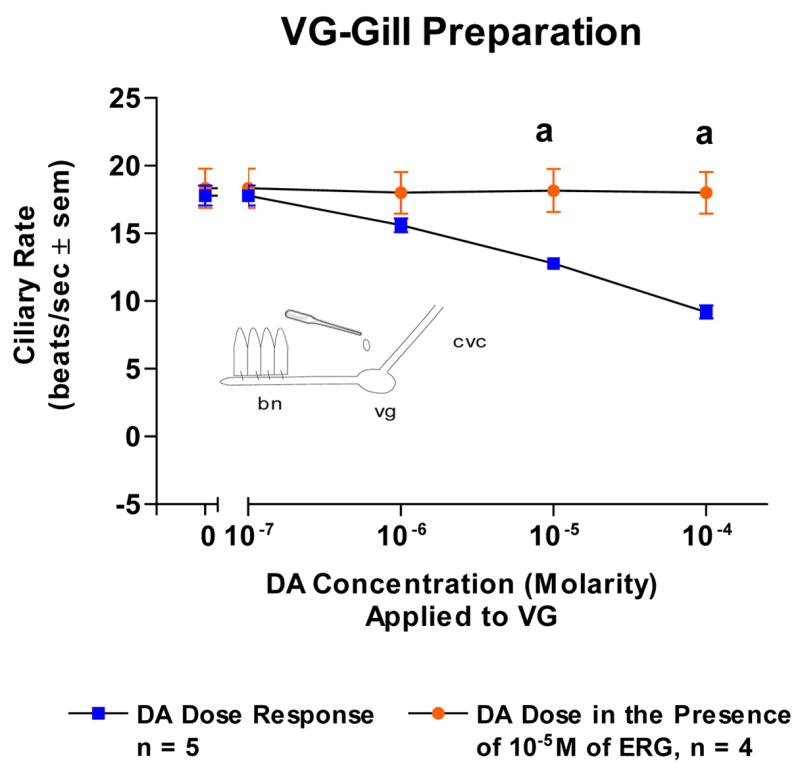

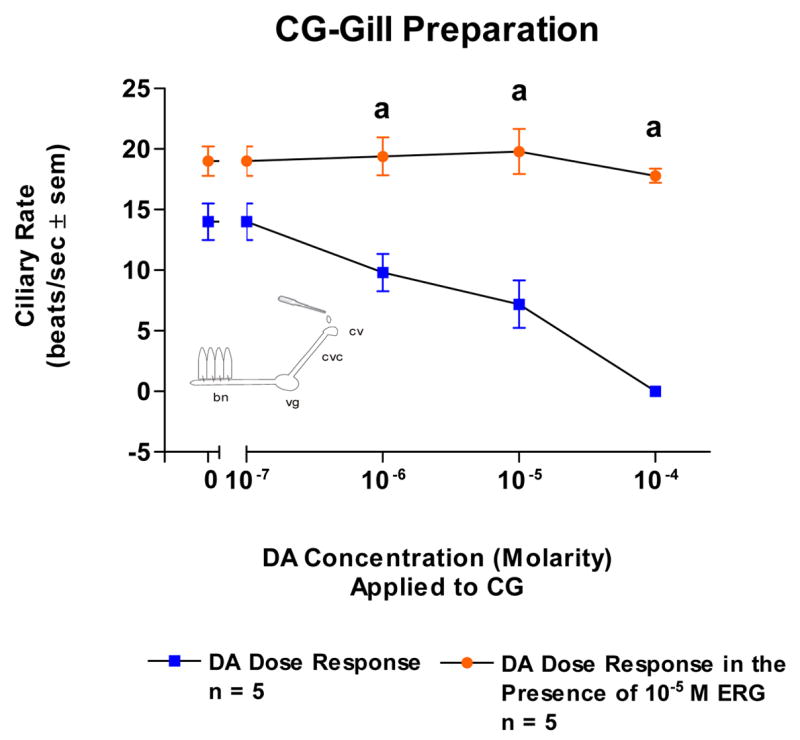

Because the basal beating rate of the lateral cilia tended to be quiescent at the start of the experiments, gills were bathed in 10−5 M 5-HT in order to have steady, high ciliary beating rates of at least 15 beats/s to study the effects of DA. Adding DA (10−7–10−4 M) to isolated gill caused a dose dependent decrease in beating rates which was blocked by pretreating the gill with ERG (10−5 M, Figure 4). Similarly, DA caused a dose dependent decrease in ciliary rates when applied to either the VG of VG preparations (Figure 5) or the CG of CG preparations (Figure 6). The cilio-inhibitory effects of DA were antagonized by pretreating the CG or VG with 10−5 M ERG.

Fig. 4.

The changes in beating rates (beats/s ± SEM) of lateral cilia in response to dopamine applied directly to excised gill with and without ERG (10−5M). The gill was activated with 10−5M serotonin when dopamine was tested. Statistical analysis was determined by t-test. ap < 0.01.

Fig. 5.

The changes in beating rates (beats/s ± SEM) of lateral cilia in response to superfusion of dopamine to the visceral ganglia of VG Preparations with and without ergonovine in the gill chamber. The gill was activated with 10−5M serotonin when dopamine was tested. Statistical analysis was determined by t-test. ap < 0.01

Fig. 6.

The changes in beating rates (beats/s ± SEM) of lateral cilia in response to superfusion of dopamine to the cerebral ganglia of CG Preparations with and without ergonovine added to the CG. The gill was activated with 10−5M serotonin when dopamine was tested. Statistical analysis was determined by t-test. ap < 0.01.

4. Discussion

The physiological mechanisms that regulate ciliary beating in most animals remain largely unknown. Studies on M. edulis have provided most of what we know about the control of ciliary activity in bivalve molluscs. Numerous studies in M. edulis have shown direct nervous system control of gill lateral ciliary activity and this regulation is mediated by a cilio-excitatory serotonergic system and a cilio-inhibitory dopaminergic system originating from the animal’s CG. While the lateral cilia of essentially all tested bivalves show a cilio-excitatory response to 5-HT and most show a cilio-inhibitory response to DA when these biogenic amines are topically applied to the gill, little work has been done to determine the role of the nervous system in regulating lateral ciliary activity in other bivalves.

We examined the role of the CNS system in controlling lateral ciliary activity in the gill of C. virginica and found it to be similar to that of M. edulis. Increasing concentrations of 5-HT, whether applied directly to excised gill filaments, or to the VG or CG, caused a dose dependent increase in lateral ciliary beating rates. This increase was blocked when MS was pre-administered to the gill or respective ganglion. Likewise, increasing concentrations of DA applied directly to excised gill filaments, or to the VG or CG, caused a dose dependent decrease in lateral ciliary beating rates. This decrease was blocked when ERG was pre-administered to the gill or respective ganglion.

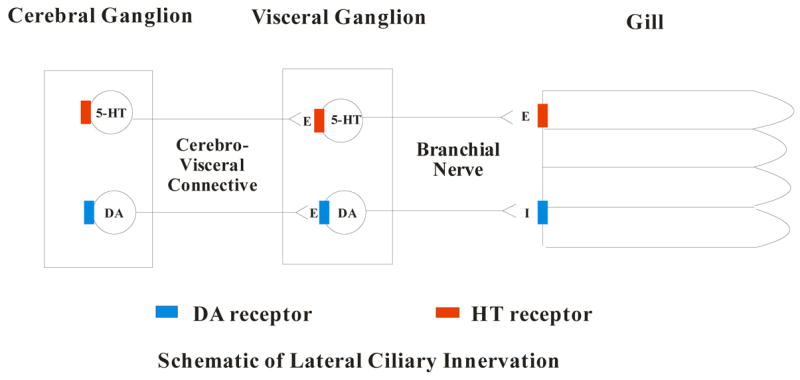

Figure 7 is a schematic representing the innervation of the gill lateral cilia by the CG and VG via the cerebrovisceral connective and the branchial nerve. It is postulated that the CG contain serotonergic and dopaminergic neurons which synapse in the VG with a second set of serotonergic and dopaminergic neurons which innervate the gill. Within the gill, the epithelial cells containing the lateral cilia have 5-HT receptors that when activated increase the ciliary beating rate and DA receptors that when activated decrease the ciliary beating rate. At both the CG and VG, 5-HT is acting as an excitor of cilio-excitatory circuits and DA is acting as an excitor of cilio-inhibitory circuits. Application of drugs to the medium bathing a ganglion can result in multiple receptor interactions. While receptors for 5-HT and DA must be present in the ganglia, it is unclear whether the applied neurotransmitter is acting directly on their respective 5-HT or DA neurons or on unidentified interneurons. However, 5-HT applications to the CG or VG only produced excitation and DA only produced inhibition of lateral ciliary beating rates. The ganglionic circuitry is not yet described and the mechanism may be polysynaptic. Complex ganglionic polysynaptic pathways, which most likely are involved with regulation of peripheral activity, may contain series of heterogenous neurons and bath application of drugs are not able to differentiate among these possibilities. Our observations should not be interpreted as indicating cilio-excitation to be exclusively mediated by ganglionic serotonergic neurons, nor cilio-inhibition exclusively by dopaminergic ganglionic neurons. This pharmacological data indicates that the presence of a reciprocal serotonergic-dopaminergic innervation controlling gill lateral cilia activity extends beyond the bivalve mollusk Mytilus, and from an evolutionary standpoint, suggests that the catecholaminergic and serotonergic relationship of neurophsyiological regulation, well established in mammals, immerged very early in evolution. This system can be used to study exogenous or endogenous chemicals that may further modulate lateral ciliary activity in C. virginica and thus provide a better understanding of the physiological mechanisms that regulate ciliary activity in bivalves and perhaps animals in general. In addition, because CNS activity is directly related to a measurable peripheral response, C. virginica can serve as a useful model with which to study serotonergic and dopaminergic systems and the drugs and chemicals that modulate the release of these biogenic amines. The preparation is relatively simple and doesn’t involve the expense or intensive surgical procedures associated with more complex animals.

Fig. 7.

Schematic of the innervation of the lateral cilia by the cerebral and visceral ganglia via the cerebrovisceral connective and the branchial nerve.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge Alisa Crawford, Turkesha Huggins, Kesha Martin and Jasmine Robinson for their work on the project, and Frank M. Flower and Sons Oyster Farm for supplying oysters. This work was supported in part by grants 2R25GM06003-05 of the Bridge Program of NIGMS, 0516041071 of NYSDOE and 67876-0036 of PSC-CUNY.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aiello EL. Factors affecting ciliary activity on the gill of the mussel Mytilus edulis. Physiol Zool. 1960;23:120–135. [Google Scholar]

- Aiello EL. Identification of the cilioexcitatory substance present in the gill of the mussel Mytilus edulis. J Cell Comp Physiol. 1962;60:17–21. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1030600103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiello EL. Nervous and chemical stimulation of gill cilia in bivalve molluscs. Physiol Zool. 1970;43:60–70. [Google Scholar]

- Aiello EL. Nervous control of gill ciliary activity in Mytilus edulis. In: Stefano GB, editor. Neurobiology of Mytilus edulis. Vol. 10. Manchester University Press; Manchester: 1990. pp. 189–208. [Google Scholar]

- Aiello E, Guideri G. Nervous control of ciliary activity. Science. 1964;146:1962–1963. doi: 10.1126/science.146.3652.1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiello E, Guideri G. Distribution and function of the branchial nerve in the mussel. Biol Bull. 1965;129:431–438. doi: 10.2307/1539722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiello E, Guideri G. Relationship between serotonin and nerve stimulation of ciliary activity. J Pharmacol Exp Therap. 1966;154:517–523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiello E, Sleigh MA. The metachronal wave of lateral cilia of Mytilus edulis. J Cell Biol. 1972;54:493–506. doi: 10.1083/jcb.54.3.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaschko H, Milton A. Oxidation of 5-hydroxytryptamine and related cornpounds by Mytilus gill plates. Br J Pharmacol. 1960;15:42–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1960.tb01208.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadet P. Nitric oxide modulates the physiological control of ciliary activity in the marine mussel Mytilus edulis via morphine: novel mu opiate receptor splice variants. Neuroendocrinol Letts. 2004;3:184–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catapane EJ. Demonstration of the peripheral innervation of the gill of the marine mollusc by means of the aluminum formaldehyde histofluorescence technique. Cell Tissue Res. 1982a;225:449–454. doi: 10.1007/BF00214696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catapane EJ. Denervation supersensitivity: A pharmacological approach. Comp Biochem Physiol C. 1982b;72:353–355. doi: 10.1016/0306-4492(82)90104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catapane EJ. Comparative study of the lateral ciliary activity in marine bivalves. Comp Biochem Physiol C. 1983;75:403–405. [Google Scholar]

- Catapane EJ, Collins ED, Marcano JA, Stefano GB. Denervation produces supersensitivity of a serotonergically innervated structure. Eur J Pharmacol. 1980;62:111–115. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(80)90487-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catapane EJ, Stefano GB, Aiello E. Pharmacological Study of the reciprocal dual innervation of the lateral ciliated gill epithelium by the CNS of Mytilus edulis (Bivalvia) J Exp Biol. 1978;74:101–113. [Google Scholar]

- Catapane EJ, Stefano GB, Aiello E. Neurophysiological correlates of the dopamine cilio-inhibitory mechanism of Mytilus edulis. J Exp Biol. 1979;83:315–323. doi: 10.1242/jeb.83.1.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catapane EJ, Thomas JA, Stefano GB, Paul DF. Effects of temperature and temperature acclimation on serotonin induced cilio-excitation of the gill of Mytilus edulis. J Thermal Biol. 1981;6:61–64. [Google Scholar]

- Dietz TH, Steffens WL, Kays WT, Silverman H. Serotonin localization in the gills of the freshwater mussel, Ligumia subrostrata. Can J Zool. 1985;63:1237–1243. [Google Scholar]

- Gainey LF, Jr, Shumway SE. The physiological effect of Aureococcus anophageflerens (“brown tide”) on the lateral cilia of bivalve mollusks. Biol Bull. 1991;181:298–306. doi: 10.2307/1542101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gainey LF, Jr, Vining KJ, Doble KE, Waldo JM, Candelario-Martinez A, Greenberg MJ. An endogenous SCP related peptide modulates ciliary beating in the gills of a venerid clam, Mercenaria mercenaria. Biol Bull. 1999;197:159–173. doi: 10.2307/1542612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gainey LF, Walton JC, Greenberg MJ. Branchial musculature of a venerid clam: Pharmacology, distribution, and innervation. Biol Bull. 2003;204:81–95. doi: 10.2307/1543498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner DB, Silverman H, Dietz TD. Musculature associated with the water canals in freshwater mussels and response to monoamines in vitro. Biol Bull. 1991;180:453–465. doi: 10.2307/1542346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosselin RE. The cilio-excitatory activity of serotonin. J Cell Comp Physiol. 1961;58:17–26. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1030580104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosselin RE. Physiologic regulators of ciliary motion. Am Rev Resp Dis. 1966;93:41–59. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1966.93.3P2.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosselin RE, Moore DE, Milton AS. Physiological control of molluscan gill cilia by 5-HT. J Gen Physiol. 1962;46:277–296. doi: 10.1085/jgp.46.2.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen CB. Comparative studies on the function of gills in suspension feeding bivalves, with special reference to effects of serotonin. Biol Bull. 1976;151:331–343. doi: 10.2307/1540666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Shenouda D, Bilfinger TV, Stefano ML, Magazine HI, Stefano GB. Morphine stimulates nitric oxide release from invertebrate microglia. Brain Res. 1996;722:125–131. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00204-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malanga CJ. Dopaminergic stimulation of frontal ciliary activity in the gill of Mytilus edulis. Comp Biochem Physiol C. 1975;51:25–34. doi: 10.1016/0306-4492(75)90033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantione KJ, Kim C, Stefano GB. Morphine regulates gill ciliary activity via coupling to nitric oxide release in a bivalve mollusk: Opiate receptor expression in gill tissues. Med Sci Monitor. 2006;12:195–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motokawa T, Satir P. Laser-induced spreading arrest of Mytilus gill cilia. J Cell Biol. 1975;66:377–391. doi: 10.1083/jcb.66.2.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paparo A. Innervation of the lateral cilia in the mussel, Mytilus edulis L. Biol Bull. 1972;143:592–604. doi: 10.2307/1540185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paparo A. The regulation of intracellular calcium and the release of neurotransmitters in the mussel, Mytilus edulis. Comp Biochem Physiol A. 1980;66:517–520. [Google Scholar]

- Paparo A. The role of the cerebral and visceral ganglia in ciliary activity. Comp Biochem Physiol A. 1985;81:647–651. [Google Scholar]

- Paparo A. Neuroregulatory activities and potassium enhancement of lateral ctenidial beating in Crassostrea virginica. Comp Biochem Physiol A. 1986a;84:585–588. [Google Scholar]

- Paparo A. DOPA decarboxylase activities and potassium stimulation of lateral cilia on the ctenidium of Crassostrea virginica (Gmelin) J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 1986b;95:225–231. [Google Scholar]

- Paparo A, Aiello E. Cilioinhibitory effect of branchial nerve stimulation in the mussel, Mytilus edulis. Comp Gen Pharmacol. 1970;1:241–50. doi: 10.1016/0010-4035(70)90059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paparo A, Finch CE. Catecholamine localization, content, and metabolism in the gill of two lamellibranch molluscs. Comp Gen Pharmacol. 1972;3:303–309. doi: 10.1016/0010-4035(72)90008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paparo A, Murphy JA. The effect of Ca on the rate of beating of lateral cilia in Mytilus edulis I. A response to perfusion with 5-HT, DA, BOL, and PBZ. Comp Biochem Physiol C. 1975;50:9–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson MJ, Dirksen ER, Satir P. The antagonistic effects of 5-hydroxytryptamine and methylxanthine on the gill cilia of Mytilus edulis. Cell Motil. 1985;5:293–309. doi: 10.1002/cm.970050403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson MJ, Satir P. Multiple effects of ethanol and 5-hydroxytryptamine on the gill cilia of Mytilus edulis. Cell Motil. 1982;2:215–224. doi: 10.1002/cm.970050403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefano GB, Aiello E. Histofluorescent localization of serotonin and dopamine in the nervous system and gill of Mytilus edulis (Bivalvia) Biol Bull. 1975;148:141 – 156. doi: 10.2307/1540655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefano GB, Cadet P, Rialas CM, Mantione K, Casares F, Goumon Y, Zhu W. Invertebrate opiate immune and neural signaling. Imm Mechan Pain Analgesia. 2003;521:126–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefano GB, Catapane EJ. The effects of temperature acclimation on monoamine metabolism. J Pharmacol Exp Therap. 1977a;203:449–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefano GB, Catapane EJ. Seasonal monoamine changes in the central nervous system of Mytilus edulis (Bivalvia) Experientia. 1977b;33:1341–1342. [Google Scholar]

- Stefano GB, Catapane EJ. Methionine enkephalin and leucine enkephalin increase dopamine in the CNS of Mytilus edulis. Society for Neuroscience Abstracts. 1978;4:283. [Google Scholar]

- Stefano GB, Catapane EJ. Enkephalins increase dopamine levels in the CNS of a marine mollusc. Life Sci. 1979;24:1617–1621. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(79)90024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefano GB, Catapane EJ, Aiello E. Dopaminergic agents: Influence on serotonin in the molluscan nervous system. Science. 1976;194:539–541. doi: 10.1126/science.973139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefano GB, Hall B, Makman MH, Dvorkin B. Opioids inhibit potassium-stimulated dopamine release in the marine mussel Mytilus edulis and in the cephalopod, Octopus bimaculatus. Science. 1981;213:928–930. doi: 10.1126/science.6266017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefano GB, Hiripi L, Catapane EJ. The effects of short and long term temperature stress on serotonin, dopamine and norepinephrine metabolism in molluscan ganglia. J Thermal Biol. 1978;3:79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Stefano GB, Salzet B, Rialas CM, Pope M, Kustka A, Neenan K, Pryor M, Salzet M. Morphine- and anandamide-stimulated nitric oxide production inhibits presynaptic dopamine release. Brain Res. 1997;763:63–68. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00403-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh JH, Moorehead M. The quantitive distribution of serotonin in invertebrates, especially in their nervous system. J Neurochem. 1960;6:146–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1960.tb13460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W, Mantione KJ, Shen L, Cadet P, Esch T, Goumon Y, Bianch E, Sonetti D, Stefano GB. Tyrosine and tyramine increase endogenous ganglionic morphine and dopamine levels in vitro and in vivo: CYP2D6 and tyrosine hydroxylase modulation demonstrates a dopamine coupling. Med Sci Monitor. 2005b;11:BR 397–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W, Mantione KJ, Shen L, Stefano GB. In vivo and in vitro L-DOPA and reticuline exposure increases ganglionic morphine levels. Med Sci Monitor. 2005a;11:MS1–MS5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]