Abstract

CXC chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) has been shown to play a critical role in chemotaxis and homing, which are key steps in cancer metastasis. There is also increasing evidence that links this receptor to angiogenesis; however, its molecular basis remains elusive. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), one of the major angiogenic factors, promotes the formation of leaky tumor vasculatures that are the hallmarks of tumor progression. Here, we investigated whether CXCR4 induces the expression of VEGF through the PI3K/Akt pathway. Our results showed that CXCR4/CXCL12 induced Akt phosphorylation, which resulted in upregulation of VEGF at both the mRNA and protein levels. Conversely, blocking the activation of Akt signaling led to a decrease in VEGF protein levels; blocking CXCR4/CXCL12 interaction with a CXCR4 antagonist suppressed tumor angiogenesis and growth in vivo. Furthermore, VEGF mRNA levels correlated well with CXCR4 mRNA levels in patient tumor samples. In summary, our study demonstrates that the CXCR4/CXCL12 signaling axis can induce angiogenesis and progression of tumors by increasing expression of VEGF through the activation of PI3K/Akt pathway. Our findings suggest that targeting CXCR4 could provide a potential new anti-angiogenic therapy to suppress the formation of both primary and metastatic tumors.

Introduction

CXCR4 has been shown to be one of the critical factors for breast cancer metastasis through interaction with its ligand, CXCL12 [1]. In our previous studies, we blocked the invasion in vitro and metastasis in vivo of breast cancer cells in an animal model by silencing the gene expression of CXCR4 with small interfering RNA [2]. These data are consistent with the requirement of CXCR4 in metastasis as demonstrated by using an anti-CXCR4 antibody or CXCR4 antagonist [1, 3].

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a critical mediator of angiogenesis and tumor proliferation [4, 5], is frequently overexpressed in variety of cancers [6, 7]. It has, therefore, emerged as a key target for researchers who are interested in development of targeted cancer therapies, rather than cytotoxic agents as a primary mode of action. While many therapeutic approaches have targeted VEGF directly, others have sought to target the upstream factors to modulate its expression level. Hypoxia inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) has been shown to regulate the expression of VEGF at both the mRNA and protein levels [8, 9]. Conversely, the expression of VEGF has shown to be regulated through HIF-1 independent mechanisms [10–12]. Here, we investigated the role of CXCR4/CXCL12 interaction in tumor angiogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and reagents

Human breast carcinoma cell line, MDA-MB-231 was routinely maintained following previous description [3]. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were cultured in M199 (Cellgro) supplemented with 20% fetal calf serum (Sigma). CXCR4 antagonist, TN14003, was synthesized by the Microchemical Core Facility at Emory University. PI3K inhibitor LY294002 was purchased from Calbiochem.

Western blotting, RT-PCR and siRNA

Extraction of RNA from Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded patient and RT-PCR have been described in our previous reports [3, 13]. Western blot analysis and RT-PCR was performed by following our previous description [3]. The construction and transfection of siRNAs against CXCR4 and transfection was described previously [2].

VEGF promoter assays

The luciferase expression vectors containing either 1.5kb or 0.2kb VEGF promoter were provided by D. Mukhopadhyay, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN [14]. The selected luciferase vector was co-transfected with CXCR4 siRNA into MDA-MB-231 cells by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). The luciferase activity was measured by using Promega luciferase assay kit in a BMG Luminometer at 48 h post-transfection.

Measurement of VEGF protein

Prior to treatment of CXCL12, MDA-MB-231 cells were pre-treated with TN14003 (100 nM) or LY294002 (5 μM) for 10 min. Cells were then treated with 200 ng/ml of CXCL12 for 24 hours. Supernatants were collected to analyze VEGF protein levels. VEGF protein levels were assayed by using a VEGF Quantikine ELISA kit (R & D Systems, Inc.) following the manufacturer’s instruction. Optical density was measured at 450 nm. VEGF concentration was calculated by comparing the data to the known standard for VEGF proteins. The unit was picogram per microgram of total protein.

Tubular network formation assay

To perform the capillary tube formation assay [15], CXCR4 antagonist TN14003, PI3K/Akt inhibitor LY294002, and VEGF antibody (Calbiochem ) were pre-incubated with human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) at 100 nM, 5 μM, and 1 μg/ml concentrations, respectively, for 10 min at room temperature before seeding. The cells were plated onto the layer of Matrigel at a density of 1x105 cells/ml of M199 medium with 1 % FBS and 200 ng/ml of CXCL12β. After 18 hrs, the wells were photographed at 4x magnification in five randomized fields and the number of their tubular networks was counted.

In vivo angiogenesis assay (Matrigel plug)

2X105 MDA-MB-231 cells were mixed with 0.5 ml of growth factor-reduced matrigel (BD Biosciences) and implanted subcutaneously into the flanks of nude mice (six mice per group). The mice in the CXCR4 antagonist-treated group received daily subcutaneous injection of TN14003 (2 mg/kg). 10 days after matrigel injection, the animals were sacrificed and the Matrigel plugs were excised. The excised plugs were photographed, weighted, and fixed for histological analysis.

Animal experiments

MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells were co-transfected with the pGL2-luciferase control vector (Promega) and a vector with puromycin resistant gene (pBABEpuro) at a 10:1 ratio using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies) according to manufacturer’s instruction. Several pooled transfected cell clones were selected by using a puromycin (1 μg /ml) and luciferase assay (Promega) according to manufacturer’s instruction. The female nude mice were subcutaneously implanted with luciferase-positive MDA-MB-231 cells with 5x106 cells/spot: two spots were injected laterally on the back of each mouse. At eight days post-tumor cell injection, the size of the tumors was measured and the mice were regrouped for even distribution of tumor sizes among various test groups. A group of 10 mice was injected twice every day intraperitoneally (i.p.) with CXCR4 antagonist TN14003 (2 μg/g body weight) while the other group was injected with control non-specific peptides as the control. After two weeks of treatment, the tumor volume was measured by a caliper. For non-invasive bioluminescence imaging, mice were anesthetized, injected with D-luciferin at 50 mg/ml i.p. (Xenogen, Alameda, CA), and imaged by the IVIS Imaging System (Xenogen).

Immunohistochemistry and quantification of tumor blood vessels

The resected primary tumors were snap-frozen in Tissue Tek O.C.T. compound and sectioned at 5-μm intervals. Sections were stained for CD31 with a rat polyclonal anti-CD31 antibody (R & D Systems). Biotin conjugated secondary antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch) was added to the tissues before the incubation of HRP-streptavidin. Finally, tissues were stained with DAB followed by the counterstaining of hematoxylin. Tumor vasculature was quantitated by counting the numbers of CD31-stained vessels in 5 randomly selected 4× microscopic fields on a Nikon Eclipse E800 microscope.

Results

CXCR4/CXCL12 induced Akt phosphorylation in MDA-MB-231 cells

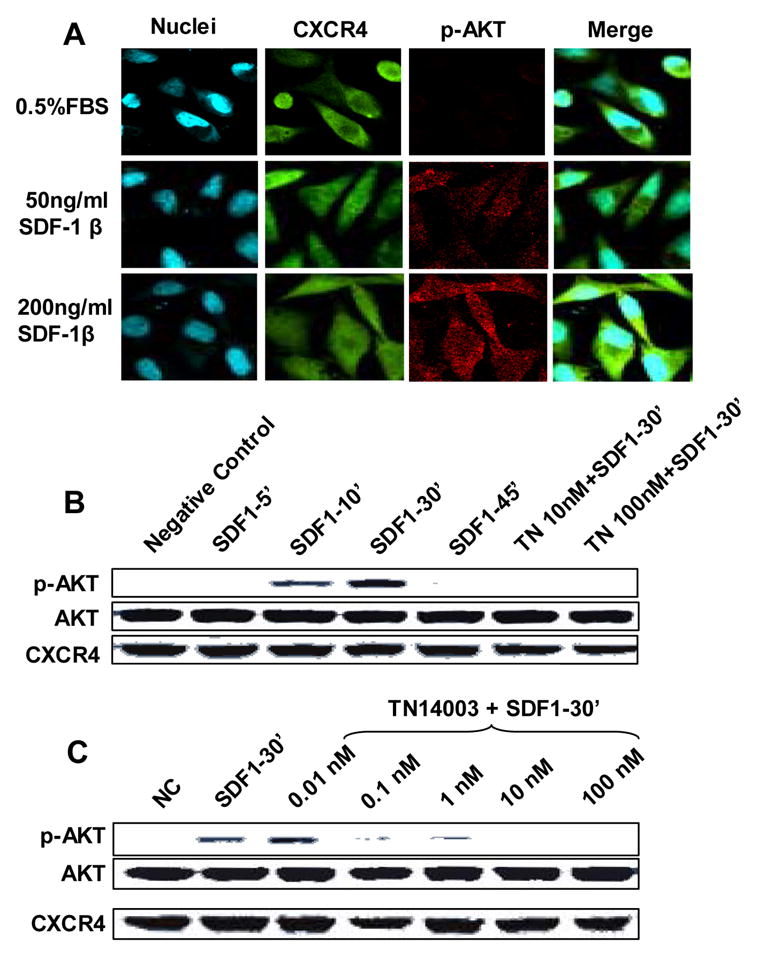

Experiments were performed to verify that CXCL12 binding induced phosphorylation of Akt (Fig. 1A). MDA-MB-231 cells were incubated in the absence and presence (50ng/ml and 200ng/ml) of CXCL12-β for 10 minutes and subsequently stained for CXCR4 (green) and pAkt (red). CXCL12 increased Akt phosphorylation in a dose-dependent manner in MDA-MB-231 cells (red). Western blot analysis confirmed that CXCL12 induced Akt phosphorylation reached a maximum level in 30 min CXCL12 (Fig. 1B), while exhibiting no effect on the total protein levels of Akt or CXCR4. Furthermore, the CXCR4 antagonist TN14003 blocked the CXCL12 induced phosphorylation of Akt in a dose-dependent manner as determined by Western blot analysis (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Induction of Akt-phosphorylation mediated by CXCR4/CXCL12 interaction. (A) CXCR4/CXCL12 induces the phosphorylation of Akt in breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells in a dose-dependent manner determined by immunofluorescence. Green represents CXCR4; red represents p-Akt; and blue represents nuclei counterstaining. (B) Western blotting showed that CXCR4/CXCL12 induced the phosphorylation of Akt at 10 min (10’) and peaked at 30 min (30’), after CXCL12 addition. Furthermore, CXCR4 antagonist TN4003 blocked the phosphorylation of Akt. (C) CXCR4 antagonist TN14003 blocked the CXCR4/CXCL12-mediated phosphorylation of Akt in a dose-dependent manner.

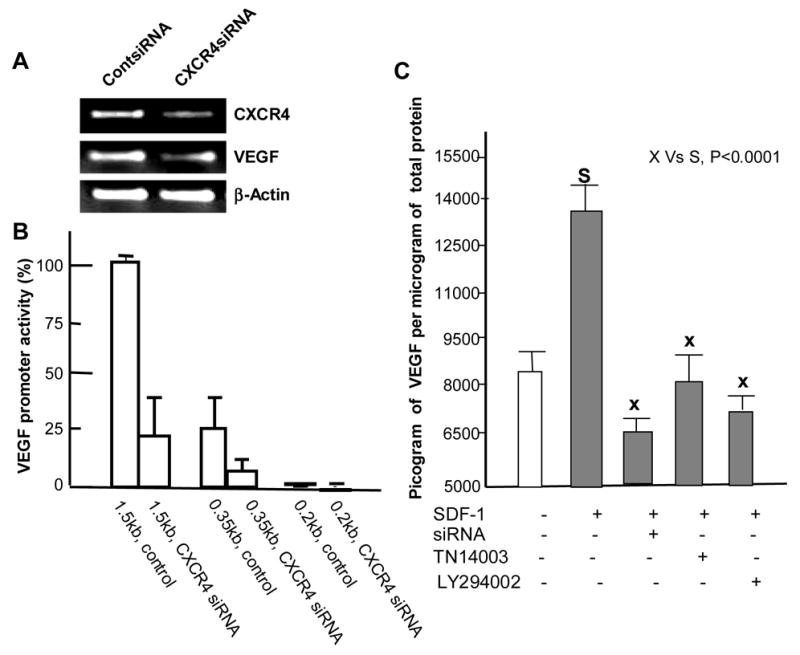

Regulation of VEGF promoter activity by CXCR4

RT-PCR analysis showed that lowering CXCR4 levels resulted in the decrease of VEGF mRNA (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, 1.5 kb or 0.35 kb VEGF promoter activity was significantly suppressed by lowering CXCR4 levels (Fig. 2B). The 0.2 kb VEGF promoter was used as a negative control [14]. To determine whether the reduced VEGF promoter activity was due to apoptosis, we utilized Annexin-V labeling. The Annexin-V labelings of control siRNA transfected cells vs. CXCR4 siRNA transfected cells were 3.2 ± 0.9 vs. 4.2 ± 1.2, respectively, which indicated that the decrease in promoter activity was not due to cell death.

Fig. 2.

CXCR4 regulates expression of VEGF. (A) CXCR4 siRNA and control siRNA transfected MDA-MB-231 cells were harvested at 48 hours post-transfection. CXCR4 and VEGF mRNA levels were detected with RT-PCR. β-actin was used as a loading control. (B) 1.5kb and 0.2 kb VEGF promoter activities were measured in CXCR4 siRNA-transfected MDA-MB-231 cells and compared to its control siRNA. (C) CXCR4/CXCL12 induced the secretion of VEGF protein in MDA-MB-231 cells. The cells were treated with serum-free medium overnight before the various treatments. For siRNA treatment, the cells were incubated with serum-free medium with CXCL12 at 24 hours post-transfection of CXCR4 siRNA. TN14003 (100 nM) and LY294002 (5 μM) were added before the addition of CXCL12. 200 ng/ml of CXCL12β was added to each well, with the exception of the negative control, and the cells were incubated overnight. The conditioned medium was collected for VEGF Quantikine ELISA assay.

CXCR4 modulates expression of VEGF via Akt pathway

VEGF secretion was enhanced up to 1.6-fold in MDA-MB-231 cells in the presence of 200ng/ml of CXCL12 when compared to cells in the absence of CXCL12 (column 1 vs column 2: Fig. 2C). Both, CXCR4 siRNA and CXCR4 antagonist reduced the secretion of VEGF in MDA-MB-231 cells (column 3 and column 4: Fig. 2C). In addition, the PI3K/Akt inhibitor LY294002 (5μM) effectively reduced VEGF secretion (column 5: Fig 2C). We recognized that decreased VEGF secretion in various compound-treated samples could be due to cytotoxicity as a result of this treatment. To determine the cell viability in the various experimental conditions in this study, MDA-MB-231 cells were treated under the same conditions as in Fig. 2C and the effects of these treatments on cell proliferation were analyzed. While the CXCR4 antagonist did not affect cell proliferation, LY294002 deceased cell viability to 81.9 ± 1.6 % at the concentration used in Fig. 2C. However, it is unlikely that the inhibition of VEGF secretion was due to the limited cytotoxic effects of those treatments on MDA-MB-231 cells.

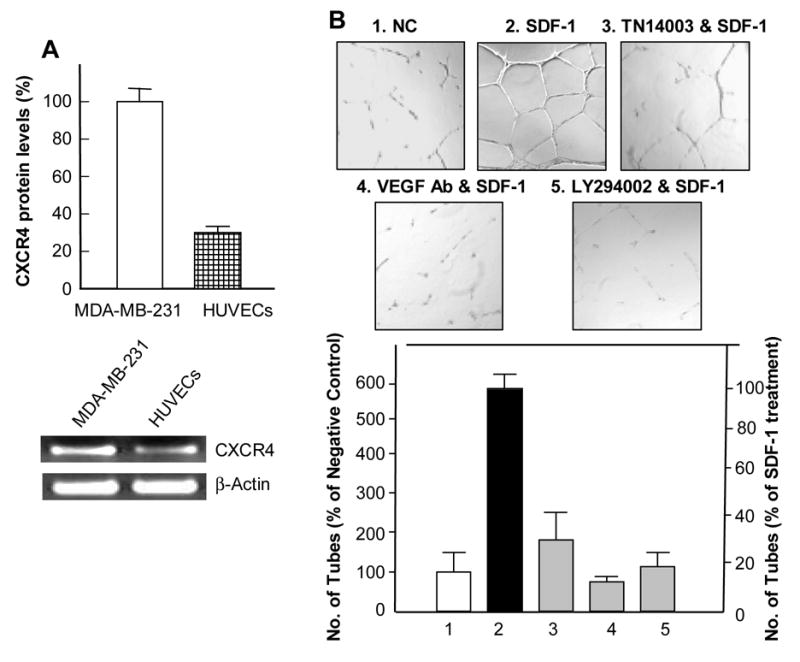

CXCR4/CXCL12 induced formations of tube-like structure in HUVECs in vitro and angiogenesis in vivo

HUVECs express moderate levels of CXCR4 mRNA and protein, although the expression levels are lower than those found in the breast cancer cell line, MDA-MB-231 (Fig. 3A). HUVECs were grown on matrigel with in presence and absence of CXCL12 for 18 hours. HUVECs grown in the presence of CXCL12 formed about 6-fold more tubes than HUVECs grown without CXCL12 (Fig. 3B1 and 3B2). CXCR4 antagonist, anti-VEGF antibody or PI3K inhibitor inhibited tubular formation induced by CXCL12 (Fig. 3B3–5). Fig. 3B (bottom panel) shows that the numbers of tubular networks were 32%, 12%, or 20% of the control, CXCL12 alone (Fig. 3B2) with pretreatment of TN14003 (100 nM) (Fig. 3B3), anti-VEGF antibody (1 μg/ml, Avastin; Genentech) (Fig. 3B4), or LY294002 (5 μM) (Fig. 3B5), respectively. HUVEC cells were treated with the same conditions as in Fig. 3B and the effects on proliferation were determined. TN14003 (100 nM) , and LY294002 (5 μM) deceased cell viability to 88 ± 5%, and 90 ± 3 %, respectively. However, it is unlikely that the inhibition of tube formation was due to the limited cytotoxic effect of the aforementioned treatments on HUVEC cells. Matrigel plug angiogenesis experiments in nude mice were performed. H&E staining of the excised plugs revealed neovasculatures and a high number of red cells in the control group treated with a scrambled peptide (Fig. 4A, right panel), which was blocked by TN14003 treatment (4A, left panel). In addition, the average plug weight in the control group as about four times heavier than the TN14003 treated group (70% reduction).

Fig. 3.

CXCR4/CXCL12 interaction induced endothelial tubular formation in HUVECs. (A) Upper panel, CXCR4 protein levels in HUVECs compared to MDA-MB-231 cells determined by immunofluorescence staining of CXCR4. Lower panel, RT-PCR of CXCR4 in HUVECs compared to MDA-MB-231 cells. (B) Representative micrographs of endothelial tubular network formation following various treatments. HUVECs formed excellent tubular networks in the presence of CXCL12 (#2) and tubular networks formation was blocked with a prior treatment of TN14003 (#3), anti-VEGF antibody (#4), or LY294002 (#5) (top panel). The results were summarized in a graph in the lower panel.

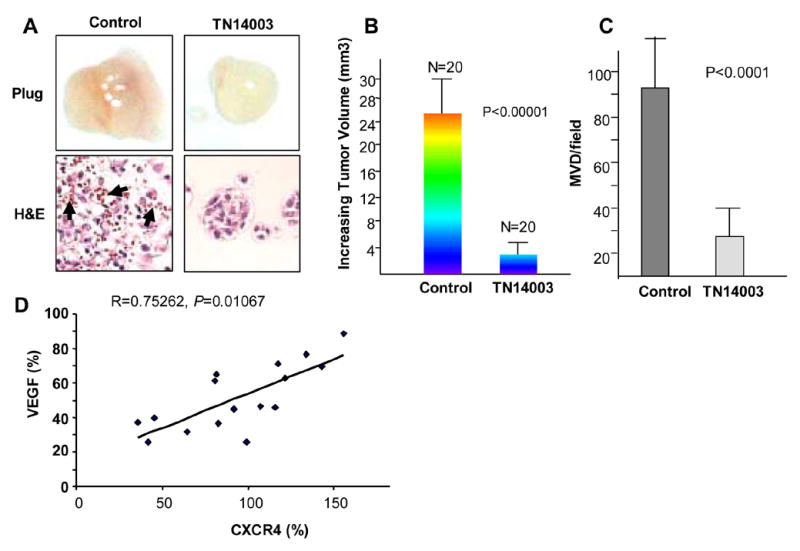

Fig. 4.

Blockade of CXCR4 inhibited angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. (A) CXCR4 antagonist TN14003 blocks in vivo angiogenesis and tumor formation in a matrigel plug. Red cells were indicated by black arrows. The average plug weight in TN14003-treated group is 30% of that in the control groups (P<0.001). (B) Blocking CXCR4/CXCL12 interaction inhibited angiogenesis and the growth of tumors in vivo. The top panel shows bioluminescent images of two representatives from TN14003-treated group vs. control group after the two week treatment. Tumor volume was of the CXCR4 antagonist treated group was only 12.4% of the tumor volume measured in the control group. Tumor volume was measured immediately before initiation of treatment and at the termination of treatment. The ratio of the volume of post- to before-treatment signifies the increase in tumor volume. Tumor volume measurements were calculated using the formula width2 × length × π/6. (C) Tumor vascularity of each sample was estimated by counting the numbers of CD31-stained vessels in five randomly selected 4x microscopic fields. (D) The correlation between CXCR4 and VEGF expression levels from breast cancer patient tumor samples. The x-axis represents CXCR4 mRNA expression levels determined by real-time RT-PCR and the y-axis represents VEGF mRNA levels (n = 16). The correlation coefficient, R=0.75262, indicates there is a strong relationship between CXCR4 and VEGF.

CXCR4 antagonist inhibited neovasculature formation and growth of tumor

5 x 106 luciferase-positive MDA-MB-231 cells were subcutaneously injected into two lateral spots on the backs of nude mice (10 mice per group). Tumor growth was monitored by non-invasive Bioluminescence imaging (BLI). Following two weeks of treatment of CXCR4 antagonist, TN14003, animals were transferred to the Xenogen Suite for BLI imaging. The intensity of light emission from the tumors in CXCR4 antagonist-treated mice was significantly less than those in control group mice (Fig. 4B, top panel), which demonstrated that the CXCR4 antagonist inhibited the growth of the MDA-MB-231 tumors in vivo. In correlation with the BLI, tumor volume taken immediately after termination of treatment shows that the average increase in tumor volume for the CXCR4 antagonist treated group was 12.7 % of the average increase in tumor volume for the control group (Fig. 4B bottom panel). Immunohistostaining of the tumor sections with anti-CD31 antibody was performed. We observed a significant reduction of microvessel density (MVD) in the tumors of CXCR4 antagonist-treated mice compared to those of the control group (Fig. 4C).

Expression of CXCR4 correlated with expression of VEGF mRNA in a selective panel of human breast cancer

We measured CXCR4 and VEGF mRNA levels from various stages of the primary tumors of breast cancer patients. The CXCR4 mRNA levels were highly correlated with VEGF mRNA levels in these 16 samples (R=0.75262, P=0.001067) (Fig. 4D).

Discussion

We have previously demonstrated that the CXCR4 antagonist TN14003 blocked CXCR4/CXCL12 mediated matrigel invasion of MDA-MB-231 cells in vitro. TN14003 treatment also inhibited lung metastasis in an experimental model for breast cancer metastasis using MDA-MB-231 cells [3]. More recently, we successfully blocked lung metastasis of MDA-MB-231 cells by silencing CXCR4 using CXCR4 siRNAs in an animal model [2]. In this study, we further determined that the blockage of the CXCR4/CXCL12 interaction could impact the growth of primary tumors.

Angiogenesis is one of the critical events, which is vital to the growth of tumors [16]. VEGF is a key factor in tumor angiogenesis [17]. Therefore, understanding the regulatory mechanisms of VEGF expression in cancer cells may have important implications for novel therapies to fight various cancers. Although HIF-1 is a potent inducer of VEGF [18, 19], high levels of VEGF expression in many cell lines under normoxic conditions imply that there are other factors regulating VEGF [20]. In fact, recent investigations showed that the expression of VEGF can be upregulated via HIF-1 independent mechanisms [11, 12, 21]. For example, activation of both HER-2/Neu and PI3K/Akt has shown to increase VEGF transcription. This effect was mediated by transcriptional activation of the VEGF promoter via Sp1 binding sites [12]. CXCR4-positive lymphohematopoietic cells were shown to exhibit phosphorylation of Akt as well as to induce VEGF secretion; however, the VEGF regulation by CXCR4 was not described [22].

In this investigation, we have shown that CXCR4 upregulates the phosphorylation of Akt and increases VEGF expression at both mRNA and protein levels. CXCL12 increases phosphorylation of Akt in a dose dependent manner, indicating a direct relationship between CXCR4/CXCL12 axis and Akt. The high basal levels of activated Erk1/2 in the MDA-MB-231 cell line due to the K-ras mutation, hinder the investigations of the impact of CXCR4/CXCL12 on Ras/MAPK pathways [23]. Inhibition of interaction between CXCR4 and CXCL12 using peptide-based CXCR4 antagonist or knockdown of CXCR4 expression by siRNAs significantly decreases the VEGF expression and angiogenesis in MDA-MB-231 cells. VEGF expression levels induced by the CXCR4/CXCL12 interaction were significantly lowered by a CXCR4 antagonist or a PI3K/Akt inhibitor. These data suggest that the CXCR4/CXCL12 axis may induce the expression of VEGF through Akt pathway. In fact, the transcriptional regulation of the VEGF promoter has been shown to be modulated through activated Akt via Sp1 binding sites [12, 24]. Furthermore, CXCR4/CXCL12 interaction induces the capillary tube formation of HUVECs in vitro (Fig. 4A) and tumor angiogenesis in vivo (Fig. 4B). Blocking the CXCR4/CXCL12 interaction with the CXCR4 antagonist TN14003 inhibited the formation of the tubes of HUVECs in a Matrigel assay, as well as tumor angiogenesis in our animal model. In addition, blocking CXCR4 interaction reduces tumor progression in vivo. We demonstrated that CXCR4 expression levels were correlated with VEGF expression levels in primary tumor tissues from breast cancer patients. Similarly, CXCL12 has been shown to induce VEGF secretion in vitro in prostate cancer cell lines PC3 and 22Rv1 [25], as well as in hematopoietic cells [22]. Taken together, these results suggest that CXCR4 upregulates the expression of VEGF at both mRNA and protein levels via the Akt pathway, which suggests that CXCR4 is a potential target of breast cancer therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a Distinguished Cancer Scientist Development Fund of Georgia Cancer Coalition and NCI R01 CA 109366 (to H. S.), and Concept Award from the Breast Cancer Research Program of the Department of Defense (BC052118) (to Z. L.) We thank Dr. Mukhopadhyay at Mayo Clinic Cancer Center for providing us with the luciferase expression vectors containing VEGF promoters. We thank Dr. Amit Maity at University of Pennsylvania and Dr. Georgia Chen at Emory University for critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank Grady Hospital Tissue Bank for providing breast tumor tissues and the Avon Foundation for the financial support to establish a tissue bank at Grady Hospital. We also thank Dr. Anthea Hammond for proof-reading.

Abbreviations

- CXCR4

CXC Chemokine receptor-4

- CXCL12 (SDF-1)

stromal cell derived factor-1

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- PI3K

Phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase

- HIF

hypoxia-inducible factor

- DAB

diaminobenzidine

- BLI

bioluminescence imaging

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Muller A, Homey B, Soto H, Ge N, Catron D, Buchanan ME, McClanahan T, Murphy E, Yuan W, Wagner SN, Barrera JL, Mohar A, Verastegui E, Zlotnik A. Involvement of chemokine receptors in breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2001;410:50–56. doi: 10.1038/35065016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liang Z, Yoon Y, Votaw J, Goodman M, William L, Shim H. Silencing of CXCR4 blocks breast cancer metastasis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:967–971. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liang Z, Wu T, Lou H, Yu X, Taichman RS, Lau SK, Nie S, Umbreit J, Shim H. Inhibition of breast cancer metastasis by selective synthetic polypeptide against CXCR4. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4302–4308. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferrara N, Hillan KJ, Gerber HP, Novotny W. Discovery and development of bevacizumab, an anti-VEGF antibody for treating cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:391–400. doi: 10.1038/nrd1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lamszus K, Ulbricht U, Matschke J, Brockmann MA, Fillbrandt R, Westphal M. Levels of soluble vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor 1 in astrocytic tumors and its relation to malignancy, vascularity, and VEGF-A. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:1399–1405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirkpatrick K, Ogunkolade W, Elkak A, Bustin S, Jenkins P, Ghilchik M, Mokbel K. The mRNA expression of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in human breast cancer. Curr Med Res Opin. 2002;18:237–241. doi: 10.1185/030079902125000633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Latil A, Bieche I, Pesche S, Valeri A, Fournier G, Cussenot O, Lidereau R. VEGF overexpression in clinically localized prostate tumors and neuropilin-1 overexpression in metastatic forms. Int J Cancer. 2000;89:167–171. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(20000320)89:2<167::aid-ijc11>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spinella F, Rosano L, Di Castro V, Natali PG, Bagnato A. Endothelin-1 induces vascular endothelial growth factor by increasing hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha in ovarian carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:27850–27855. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202421200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamakawa M, Liu LX, Date T, Belanger AJ, Vincent KA, Akita GY, Kuriyama T, Cheng SH, Gregory RJ, Jiang C. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 mediates activation of cultured vascular endothelial cells by inducing multiple angiogenic factors. Circ Res. 2003;93:664–673. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000093984.48643.D7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duyndam MC, Hulscher ST, van der Wall E, Pinedo HM, Boven E. Evidence for a role of p38 kinase in hypoxia-inducible factor 1-independent induction of vascular endothelial growth factor expression by sodium arsenite. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:6885–6895. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206320200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mizukami Y, Li J, Zhang X, Zimmer MA, Iliopoulos O, Chung DC. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1-independent regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor by hypoxia in colon cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:1765–1772. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pore N, Liu S, Shu HK, Li B, Haas-Kogan D, Stokoe D, Milanini-Mongiat J, Pages G, O'Rourke DM, Bernhard E, Maity A. Sp1 is involved in Akt-mediated induction of VEGF expression through an HIF-1-independent mechanism. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:4841–4853. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-05-0374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shim H, Lau SK, Devi S, Yoon Y, Cho HT, Liang Z. Lower expression of CXCR4 in lymph node metastases than in primary breast cancers: potential regulation by ligand-dependent degradation and HIF-1alpha. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;346:252–258. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.05.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mukhopadhyay D, Knebelmann B, Cohen HT, Ananth S, Sukhatme VP. The von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor gene product interacts with Sp1 to repress vascular endothelial growth factor promoter activity. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5629–5639. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Z, Zhang X, Li M, Wang Z, Wieand HS, Grandis JR, Shin DM. Simultaneously targeting epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase and cyclooxygenase-2, an efficient approach to inhibition of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:5930–5939. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bergers G, Benjamin LE. Tumorigenesis and the angiogenic switch. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:401–410. doi: 10.1038/nrc1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferrara N. VEGF and the quest for tumour angiogenesis factors. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:795–803. doi: 10.1038/nrc909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bruick RK, McKnight SL. Building better vasculature. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2497–2502. doi: 10.1101/gad.931601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ozaki H, Yu AY, Della N, Ozaki K, Luna JD, Yamada H, Hackett SF, Okamoto N, Zack DJ, Semenza GL, Campochiaro PA. Hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha is increased in ischemic retina: temporal and spatial correlation with VEGF expression. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:182–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feldkamp MM, Lau N, Rak J, Kerbel RS, Guha A. Normoxic and hypoxic regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) by astrocytoma cells is mediated by Ras. Int J Cancer. 1999;81:118–124. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990331)81:1<118::aid-ijc20>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arsham AM, Plas DR, Thompson CB, Simon MC. Akt and hypoxia-inducible factor-1 independently enhance tumor growth and angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3500–3507. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kijowski J, Baj-Krzyworzeka M, Majka M, Reca R, Marquez LA, Christofidou-Solomidou M, Janowska-Wieczorek A, Ratajczak MZ. The SDF-1-CXCR4 axis stimulates VEGF secretion and activates integrins but does not affect proliferation and survival in lymphohematopoietic cells. Stem Cells. 2001;19:453–466. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.19-5-453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davidson NE, Gelmann EP, Lippman ME, Dickson RB. Epidermal growth factor receptor gene expression in estrogen receptor-positive and negative human breast cancer cell lines. Mol Endocrinol. 1987;1:216–223. doi: 10.1210/mend-1-3-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finkenzeller G, Weindel K, Zimmermann W, Westin G, Marme D. Activated Neu/ErbB-2 induces expression of the vascular endothelial growth factor gene by functional activation of the transcription factor Sp 1. Angiogenesis. 2004;7:59–68. doi: 10.1023/B:AGEN.0000037332.66411.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Darash-Yahana M, Pikarsky E, Abramovitch R, Zeira E, Pal B, Karplus R, Beider K, Avniel S, Kasem S, Galun E, Peled A. Role of high expression levels of CXCR4 in tumor growth, vascularization, and metastasis. Faseb J. 2004;18:1240–1242. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0935fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.