Abstract

We tested the psychometric properties and predictive validity of a newly developed 8-item measure of commitment to quitting smoking, conceptualized as the state of being personally bound or obligated to persist in quitting smoking despite potential difficulties, craving and discomfort. Participants were 157 heavy drinking smokers enrolled in a clinical trial of smoking cessation treatments. The measure showed strong unidimensionality, good internal consistency, and moderate stability from baseline to quit date. Commitment significantly increased from baseline to quit date. Higher commitment to quitting at baseline predicted greater odds of abstinence at post-treatment and 16 and 26 weeks after quit date. Commitment predicted smoking outcome over and above level of tobacco dependence, self-reported importance of quitting smoking, and self-efficacy for remaining abstinent. Results suggest that commitment is a highly relevant construct for smoking cessation, which can be reliably assessed with the Commitment to Quitting Smoking Scale and which may be an excellent target for smoking cessation treatments.

Keywords: Addictions, Psychometrics, Measurement, Smoking Cessation, Commitment, Motivation

1. Introduction

Commitment is defined as “the state of being bound emotionally or intellectually to a course of action” (American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 2000). Greater commitment is reflected in statements such as “I will…” as opposed to “I want to…” or “I will try to…” and individuals who are highly committed are likely to use expressions such as “whatever it takes” or “no matter how difficult” in their statements regarding a course of action. In this way, commitment is conceptually distinct from related constructs such as desire to quit (“I very much want to quit”) and self-efficacy (“I am confident that I can quit successfully”). Recent work by Amrhein and colleagues using linguistic analyses (Amrhein, Miller, Yahne, Palmer, & Fulcher, 2003) has highlighted the importance of commitment in understanding and predicting behavioral change. However, we know of no self-report multi-item measure that has been developed specifically to assess the construct of commitment to quitting smoking.

In the present study, we tested the psychometric properties and concurrent and predictive validity of a multi-item self-report measure of commitment to quitting smoking, which we conceptualized as a cognitive state of being personally bound or obligated to avoid smoking despite any potential difficulty, discomfort, or craving associated with quitting, even when the magnitude and duration of that discomfort are unknown and variable.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Participants were 157 smokers recruited from the community as part of a larger, randomized clinical trial. To be included, participants had to: (a) be ≥18 years of age; (b) have smoked regularly for at least one year; (c) smoke at least 10 cigarettes a day; (d) use no other tobacco products or nicotine replacement therapy; and (e) drink heavily according to self-report (>14 drinks per week or ≥5 drinks per occasion at least once per month over the last 12 months for men; >7 drinks per week or ≥4 drinks per occasion at least once per month over the past 12 months for women). Participants were excluded if they: (a) were alcohol dependent; (b) met criteria for other current psychoactive substance abuse or dependence; (c) met criteria for major depression or mania; (d) were psychotic or suicidal; (e) had an medical condition that would preclude use of the nicotine patch; (f) were pregnant, lactating or intended to become pregnant.

The sample used in these analyses was 49.0% (n = 77) female and 93.6% non-Hispanic White. The mean age of the sample was 41.6 (SD = 11.4) years, and the mean education was 14.2 (SD = 2.2) years. Participants smoked an average of 21.2 (SD = 8.3) cigarettes per day and had been smoking for an average of 22.8 years (SD = 11.3). The mean on the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND; Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, & Fagerström, 1991) was 4.9 (SD = 2.0). Participants drank an average of 15.9 (SD = 11.1) drinks per week.

2.2. Procedure

Participants were recruited from the community using newspaper and radio advertisements. They were screened by telephone before completing an intake interview, at which they signed a statement of informed consent approved by the Brown University Institutional Review Board. Treatment consisted of four individual behavioral counseling sessions over three weeks with the quit date occurring at session 2, one week after session 1. Sessions focused on problem solving regarding high-risk situations for smoking relapse, providing support within the treatment, and encouraging participants to seek support for quitting smoking outside of treatment. All participants received transdermal nicotine patch (4 weeks at 21 mg, 2 weeks at 14 mg, and 2 weeks at 7 mg). In one treatment condition there was an extended relaxation training module, while in the other there was a extended module focusing on alcohol use.

2.3. Measures

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies –Depression scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). Participants’ perceived importance of quitting smoking was assessed with a single item “How important is it to you to quit smoking now?” with an 11-point scale from 0 = not at all important to 10 = extremely important. This measure is similar to that used by Marlatt and colleagues (1988). Smoking cessation self-efficacy was measured using a well-validated 9-item scale (Velicer, Diclemente, Rossi, & Prochaska, 1990).

Seven-day point prevalence abstinence was assessed at 8, 16, and 26 weeks after participants’ quit date. Abstinence was confirmed by a combination of CO ≤ 10 ppm and cotinine ≤ 15 ng/ml (at 16 and 26-week follow-ups) or by a collateral informant. Complete smoking data were obtained from 93.6%, 91.2%, and 92.4% of participants at the 8-, 16-, and 26-week follow-ups, respectively. Individuals who had missing data were considered smoking.

2.4. The Commitment to Quitting Smoking Scale (CQSS)

The eight items used to assess commitment to quitting smoking are presented in Table 1. The response scale ranged from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. Items were selected based on rational criteria to cover a range of statements reflecting commitment to quitting despite possible difficulties. The CQSS was administered at baseline and immediately prior to session 2.

Table 1.

Item Content, Sample Means, and Standard Deviations of the Commitment to Quitting Smoking Scale

| Item Content | Sample Mean | Sample SD |

|---|---|---|

| 1. I’m willing to put up with whatever discomfort I have to in order to quit smoking. | 4.14 | 0.79 |

| 2. No matter how difficult it may be, I won’t let myself smoke once I quit. | 3.85 | 0.84 |

| 3. Feeling very anxious or restless won’t prevent me from quitting smoking. | 3.76 | 0.75 |

| 4. Even if I really want one, I won’t let myself pick up a cigarette once I quit. | 3.80 | 0.81 |

| 5. No matter how much I crave a cigarette when I quit, I’m going to resist the urge to smoke. | 4.03 | 0.76 |

| 6. Feeling very depressed or sad won’t prevent me from quitting smoking. | 3.87 | 0.79 |

| 7. I’m not going to let anything get in the way of my quitting smoking. | 3.96 | 0.78 |

| 8. Feeling very angry and irritable won’t prevent me from quitting smoking. | 3.84 | 0.82 |

Note. Response options for the items range from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.

3. Results

3.1. Psychometrics of the CQSS

Table 1 shows the means and standard deviations for each item on the CQSS. Results of principal iterated common factors analysis provided very strong support for there being one primary dimension assessed by the scale. The first factor had an eigenvalue of 4.66 (second factor = 0.46), accounting for 91.0% of common variance among items. All items loaded highly on the first factor ranging from .69 (item 6) to .83 (item 5). The internal consistency of the 8 items was very high with a Cronbach’s alpha of .91, and no items detracted from alpha.

Concurrent Validity

The mean CQSS score in the sample was 3.9 (SD = .63; range = 2 – 5), with 14 (8.9%) participants scoring at the maximum possible value of 5. Women (M = 4.0, SD = .60) scored significantly higher than men (M = 3.8, SD = .63), t(155) = 2.30, d = 0.37, p = .02. Commitment was not significantly correlated with age, education, number of cigarettes smoked per day, drinks consumed per week, or FTND score, rs(157) = −.13, −.02, .07, −.10, and .00, respectively. Depressive symptoms at session 1 were negatively and significantly correlated with commitment, r(157) = −.18, p = .03.

The mean level of self-reported importance of quitting smoking in the sample was 9.0 (SD = 1.3) on a 0 to 10 scale. Eighty-six participants (54.8%) endorsed the highest value of 10. Commitment to quitting was significantly correlated with the perceived importance of quitting, r(157) = .38, p < .0001. The mean level of self-efficacy in the sample was 2.6 (SD = 0.9) on a 1 to 5 scale. The correlation between CQSS score and self-efficacy was positive and significant, r(157) = .30, p < .0001. The correlation between importance of quitting and self-efficacy was small and nonsignificant, r(157) = .07, p = .37.

Change in Commitment

Commitment at session 2 (i.e., on the quit date) was obtained for 151 participants (96.2%). At this time, the mean level of commitment was 4.2 (SD = .73), with 34 participants (22.5%) scoring the maximum value of 5. Commitment significantly increased from baseline to session 2, d = 0.35, F(1,150) = 18.1, p < .0001, and demonstrated modest stability across time, r(151) = .42, p < .0001. By comparison, the perceived importance of quitting significantly increased from 9.0 (SD = .63) at baseline to 9.3 (SD = 1.1) at session 2, an increase that also was significant, d = 0.22, F(1,150) = 5.8, p < .01. Stability of perceived importance was similar to that of commitment, r(151) = .48, p < .0001. Self-efficacy increased more notably from 2.6 (SD = 0.9) at baseline to 3.7 (SD = .74) at session 2, d = 1.09, F(1,149) = 178.7, p < .0001. Self-efficacy was more variable from baseline to session 2, r(150) = .23, p < .01, with this stability coefficient being significantly less than that of commitment, p < .01.

3.2. Commitment to Quitting and Smoking Outcome

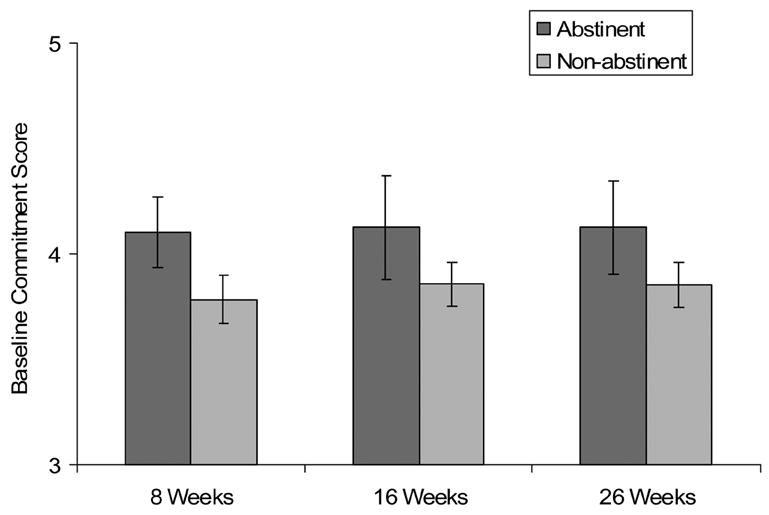

Overall point-prevalence smoking abstinence rates at 8, 16 and 26 weeks were 38.2%, 17.8%, and 18.5%. Mean CQSS score by abstinence status at each follow-up are shown in Figure 1. At each follow-up, those who were abstinent had significantly higher commitment scores at baseline than those who were not abstinent, ds = 0.52, 0.43, and 0.44, respectively, ps < .05.

Figure 1.

Means and 95% confidence intervals for baseline commitment to quitting smoking comparing those who were abstinent from smoking at that follow-up to those who were not abstinent at that follow-up. Commitment scores can range from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.

Repeated measures analyses for binomial outcomes were conducted using generalized estimating equations with point prevalence abstinence at the three time periods as the dependent variable. Independent variables included commitment, gender, FTND score, and a variable carrying the linear effect of time. Results indicated that greater commitment was associated with higher odds of abstinence across follow-up (B = 0.84, SE = 0.28, odds ratio[OR] = 2.32, p = .003). Finally, we ran a GEE analysis including commitment, perceived importance of quitting, and self-efficacy for quitting. The effect of commitment was significant (B = −0.72, SE = .34, OR = 2.05, p = .036), whereas the effects of importance and self-efficacy were not, ps > .50.

4. Discussion

The CQSS appears to offer a brief, reliable, and valid assessment of commitment to quitting smoking that avoids the ceiling effects we obtained with a single item assessment of importance of quitting. Conceptualized as a state of being personally bound to persist in quitting smoking despite difficulties, cravings, and negative affect, commitment was related to, yet distinguishable from, the perceived importance of quitting smoking and self-efficacy for quitting. Greater commitment to quitting was associated with higher odds of abstinence from smoking at follow-up, and its effect was stronger than those of perceived importance of quitting and self-efficacy for quitting. Research on factors associated with greater commitment to quitting and development of treatments that specifically target commitment would be valuable in further explicating the potential role of commitment in smoking cessation.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant DA15534 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to Dr. Christopher W. Kahler.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American heritage dictionary of the English language. 4. Boston, MA: Houghton-Mifflin; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Amrhein PC, Miller WR, Yahne CE, Palmer M, Fulcher L. Client commitment language during motivational interviewing predicts drug use outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:862–878. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence: A revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Curry S, Gordon JR. A longitudinal analysis of unaided smoking cessation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56:715–720. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.5.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977 Summer;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Velicer WF, Diclemente CC, Rossi JS, Prochaska JO. Relapse situations and self-efficacy: An integrative model. Addictive Behaviors. 1990;15:271–283. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(90)90070-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]