Abstract

Pop6 and Pop7 are protein subunits of Saccharomyces cerevisiae RNase MRP and RNase P. Here we show that bacterially expressed Pop6 and Pop7 form a soluble heterodimer that binds the RNA components of both RNase MRP and RNase P. Footprint analysis of the interaction between the Pop6/7 heterodimer and the RNase MRP RNA, combined with gel mobility assays, demonstrates that the Pop6/7 complex binds to a conserved region of the P3 domain. Binding of these proteins to the MRP RNA leads to local rearrangement in the structure of the P3 loop and suggests that direct interaction of the Pop6/7 complex with the P3 domain of the RNA components of RNases MRP and P may mediate binding of other protein components. These results suggest a role for a key element in the RNase MRP and RNase P RNAs in protein binding, and demonstrate the feasibility of directly studying RNA–protein interactions in the eukaryotic RNases MRP and P complexes.

Keywords: ribonuclease MRP, ribonuclease P, Pop6, Pop7, RNA–protein interactions, footprinting

INTRODUCTION

Nuclear RNases MRP (Chang and Clayton 1987; Karwan et al. 1991) and P (Altman and Kirsebom 1999) are ribonucleoprotein complexes that contain a single RNA molecule, typically 250–400 nucleotides (nt) long and with 9–12 protein components. RNase P is a ubiquitous endoribonuclease whose main function is to cleave the 5′ leader from the end of precursor tRNAs (Altman and Kirsebom 1999). RNase MRP is a universal eukaryotic enzyme that, like RNase P, is found both in mitochondria and in the nucleus (Chang and Clayton 1987). Yeast nuclear RNase MRP was shown to be involved in the processing of rRNA (Schmitt and Clayton 1993; Lygerou et al. 1996) and in regulation of the cell cycle through the degradation of specific mRNAs (Gill et al. 2004).

The catalytic role of the RNA component in bacterial and archaeal RNase P is well established (Walker and Engelke 2006), and the high level of phylogenetic conservation of the key nucleotides (Frank and Pace 1998) strongly suggests that in eukaryotic RNase P, the RNA component is responsible for catalysis as well. Indeed, recent findings demonstrate that eukaryotic RNase P RNA alone can bind its substrate specifically (Marquez et al. 2006) and is capable of catalysis, albeit with very low efficiency (Kikovska et al. 2007). The RNA components of RNases MRP and P show striking similarity in the regions that are expected to be involved in catalysis (Forster and Altman 1990; Li et al. 2002). The protein compositions of RNases MRP and P are also remarkably similar. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, RNase P has nine known essential protein components (Pop1, Pop3, Pop4, Pop5, Pop6, Pop7, Pop8, Rpp1, and Rpr2), at least eight of which are also a part of RNase MRP (Chamberlain et al. 1998). RNase MRP contains two proteins not found in RNase P, Snm1, which is related to Rpr2 (Schmitt and Clayton 1994), and Rmp1 (Salinas et al. 2005). The role(s) of the proteins in the structure and function of RNases MRP and P has not yet been established.

The direct study of the protein–protein and RNA–protein interactions in the yeast RNases MRP and P was hampered by insolubility and aggregation of the individual protein components (Houser-Scott et al. 2002). Hence, the limited information available was derived from either two- and three-hybrid studies or from mutational data.

The amino acid sequences of the protein components of RNases MRP and P contain substantial hydrophobic patches, suggesting an important role for hydrophobic interactions in stabilization of RNase MRP and RNase P complexes. These patches may also result in the insolubility or aggregation of individual proteins, hindering attempts to study RNA–protein and protein–protein interactions directly. A solution to this problem is to identify groups or subcomplexes of individual proteins that are sufficiently stable to allow application of direct techniques such as gel mobility-shift assays and footprint analysis.

Previous two-hybrid studies suggested that RNase MRP and RNase P proteins Pop6 and Pop7 strongly interact with each other (Houser-Scott et al. 2002), therefore presenting an opportunity to test the approach of using a protein subcomplex instead of individual proteins to study RNA–protein interactions directly. This proved to be correct, and here we present the results of direct studies of interaction between Pop6/Pop7 complex and the RNase MRP/RNase P RNAs.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Proteins Pop6 and Pop7 form a soluble heterodimer

Fusion of purification tags or other polypeptides can lead to aberrant results, as those additions can interfere with the proper protein folding. This problem is even more pronounced when a complex of two or more proteins is to be studied. In order to obtain more definitive results, we expressed the Pop6 and Pop7 proteins without any changes from the wild-type sequence.

Coexpression of Pop6 (18.2 kDa) and Pop7 (15.8 kDa) in Escherichia coli yielded a soluble complex, consistent with the results of two-hybrid studies (Houser-Scott et al. 2002). The complex did not dissociate at salt concentrations as high as 0.5 M KCl and did not show any tendency to aggregate in 50 mM KCl at concentrations up to 10 mg/mL (data not shown). The mobility of the complex in a gel-filtration column was consistent with a Pop6/Pop7 heterodimer. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) experiments indicated a 100% homogenous sample with a particle size of 2.94 nm (data not shown), also consistent with a heterodimer. To confirm the stoichiometry of the complex, it was separated on a 15% denaturing SDS–polyacrylamide gel and stained with SYPRO-Orange dye (Fig. 1). Quantification of the intensities of the bands demonstrated (1.2 ± 0.2):1 weight:weight Pop6:Pop7 ratio, which corresponds to (1.04 ± 0.17):1 molar ratio, confirming that Pop6 and Pop7 form a heterodimer.

FIGURE 1.

Varying amounts (0.25–1 μg) of purified Pop6/7 complex fractionalized on a 15% SDS–polyacrylamide gel and stained with SYPRO Orange. Purified Pop6 was loaded as a control (left lane). Quantification of the intensities of the bands shows 1:1 Pop6: Pop7 molar ratio. Combined with Dynamic Light Scattering data (particle size 2.94 nm), this indicates formation of a heterodimer.

Interestingly, Pop6 could also be purified to homogeneity alone, producing monomers with a particle size (determined by DLS) of 2.05 nm. This Pop6 monomer was soluble at concentrations up to 15 mg/mL in 100 mM KCl without any signs of aggregation. We were unable to produce homogeneous Pop7, as it aggregated when expressed alone.

Pop6/7 complex binds P3 domain of RNase MRP and RNase P RNA

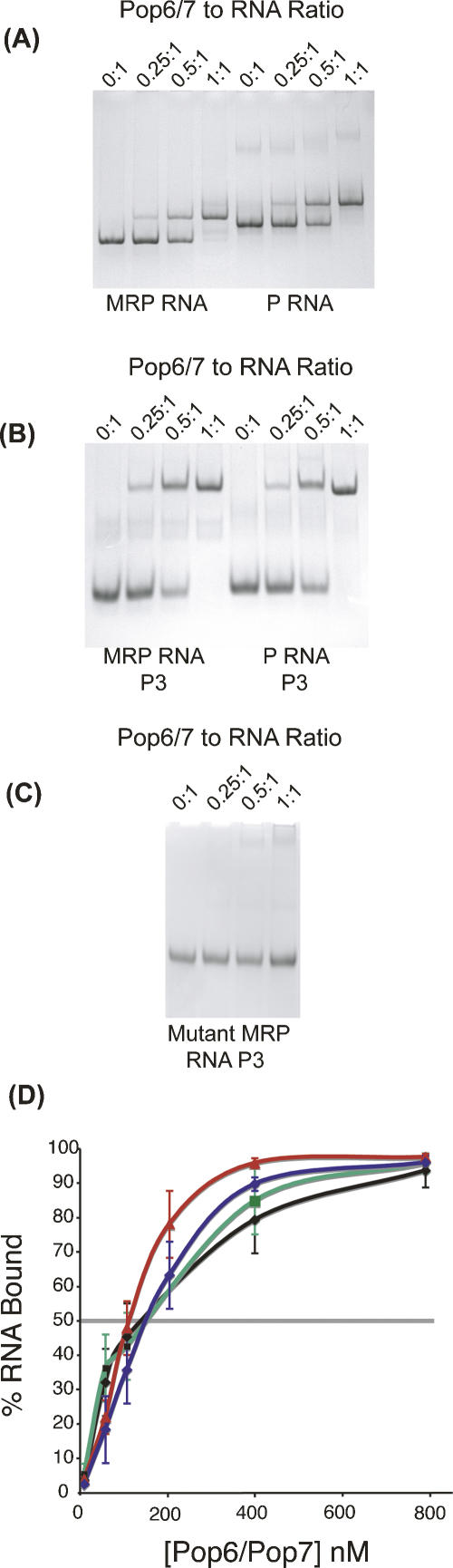

Incubation of the Pop6/7 complex with RNase MRP or RNase P RNA resulted in formation of RNA–protein complexes, in which one Pop6/7 heterodimer bound one RNA molecule (Fig. 2A). To determine the stoichiometry, the complexes were formed at concentrations of the components that were at least an order of magnitude higher than the binding constant (below). We did not observe binding of Pop6/7 to tRNA or to a control (“antisense”) RNA that was complementary to the RNase MRP RNA. The Pop6 monomer was unable to bind either RNase MRP or RNase P RNAs (data not shown). It appears that formation of Pop6/7 complex is necessary for RNA binding. It is possible that the presence of the Pop7 is required for proper folding of some parts of Pop6 and, therefore, the observed inability of Pop6 alone to bind RNA does not exclude that Pop6 may be involved in (or be solely responsible for) interaction with RNA as a part of a complex with Pop7.

FIGURE 2.

Binding of Pop6/7 heterodimer to RNA. (A) Binding of Pop6/7 heterodimer to the full-length RNase MRP RNA (left lanes) or RNase P RNA (right lanes). Pop6/7 heterodimer binds both RNAs with 1:1 stoichiometry. (B) Binding of Pop6/7 heterodimer to the P3 domain from RNase MRP RNA (left lanes) or RNase P RNA (right lanes). Pop6/7 heterodimer binds both P3 domains. (C) Interaction of Pop6/7 with the mutated (U35A, U36A, A37U, C38G) P3 domain of RNase MRP. To determine the stoichiometry in A–C, the complexes were formed at concentrations of the components that were by at least an order of magnitude higher than the binding constant. The samples were loaded on 4% native polyacrylamide gels and fractionated at 4C; the gels were stained with toluidine blue. (D) Binding curves from filter-binding assays: binding with RNase MRP RNA (no competitor), triangles, red; with RNase MRP RNA (with 100X excess of tRNA), circles, blue; with P3 domain of RNase MRP (with 100X excess of tRNA), squares, black; with P3 domain of RNase P (with 100X excess of tRNA), squares, green.

To estimate the binding constant for the Pop6/7 MRP–RNA complex, we performed filter-binding assays (Fig. 2D). The resulting constant for the complex of Pop6/7 with RNase MRP RNA was estimated to be 110 ± 40 nM without any competitor present, while in the presence of 100-fold excess of competitor yeast tRNA, the binding constant was estimated to be 150 ± 40 nM. The relative weakness of binding of Pop6/7 to RNase MRP RNA probably reflects the fact that in the RNase MRP holoenzyme, additional protein subunits act synergistically to stabilize the complex. Tight binding may require interactions with other protein components, which, in turn, interact with the RNA themselves. One might speculate that because of the relatively weak binding, Pop6/7 may not be the first protein components to bind the RNase MRP RNA during the holoenzyme assembly in vivo. The presence of other protein components, already bound to the RNA, could significantly strengthen binding of Pop6/7. Three-hybrid studies suggest that the Pop4 protein interacts with Pop6, Pop7, and the RNA component of RNase MRP (Houser-Scott et al. 2002). This makes Pop4 a possible candidate for a protein that binds the RNA component during the early stages of RNase MRP assembly.

To localize the Pop6/7-binding site on the RNase MRP RNA, we performed RNA-footprint analysis using RNase A (cleaving RNA at accessible single-stranded pyrimidines) and RNase V1 (cleaving double-stranded or stacked RNA) as probes (Fig. 3). As can be seen, Pop6/7 binding causes specific changes in the sensitivity of the RNase MRP RNA to RNases. Those changes are localized to the P3 domain, which spans nucleotides 28 through 79 (Figs. 3, 4). No other changes in the RNA were detected upon binding by the Pop6/7 heterodimer.

FIGURE 3.

Footprint analysis of the Pop6/7–RNase MRP RNA complex, 6% denaturing (8 M urea) polyacrylamide gel. (Lanes 1,2) Control (untreated 5′-end labeled RNA) without and with Pop6/7; (lanes 3–8) digest with varying amounts of RNase V1 (lanes 3–5) without Pop6/7; (lanes 6–8) with Pop6/7; (lane 9) RNA digest with RNase T1 (G-ladder); (lane 10) alkali hydrolysis (ladder); (lanes 11–18) digest with varying amounts of RNase A (lanes 11–14) without Pop6/7; (lanes 15–18) with Pop6/7. The effects of binding of Pop6/7 heterodimer to RNase MRP RNA are confined to the P3 domain (marked on the right). Pop6/7 binding results in protection of nucleotides 30–38 (shown by a white box) and increases sensitivity of nucleotides G49, U76, and U77, to RNase V1 and U67 to RNase A.

FIGURE 4.

Expected secondary structures of the RNA components of S. cerevisiae RNase MRP (A) and RNase P (B). The diagrams and the nomenclature of the structural elements are based on Frank et al. (2000) and Li et al. (2002). (C) P3 domain of S. cerevisiae RNase MRP. The nucleotides common in RNase MRP and RNase P are circled. The nucleotides protected by Pop6/7 binding to RNase MRP RNA are marked by a bold line. The nucleotides that become more sensitive to nucleases upon Pop6/7 binding are marked by asterisks.

To test if the P3 domain was sufficient for Pop6/7 binding, we synthesized the P3 domain of the yeast RNase MRP alone and tested it for in vitro binding to the Pop6/7 heterodimer using gel mobility-shift experiments. As can be seen, these results confirmed that the P3 domain from the RNase MRP RNA was sufficient for Pop6/7 binding (Fig. 2B). A filter-binding assay estimation of the binding constant for the interaction with the P3 domain of RNase MRP alone gave 140 ± 60 nM with yeast tRNA present in 100-fold excess over RNA, a value similar to that obtained for the interaction with the whole-length RNase MRP RNA (150 ± 40 nM, above).

Protection of several nucleotides in the P3 domain upon Pop6/7 binding in vitro, combined with formation of stable complexes of Pop6/7 with P3 domain alone, strongly suggest that the P3 domain is a binding site for the Pop6/7 heterodimer. However, it is possible that in the holoenzyme, Pop6/7–RNA interactions may be more complicated. RNase MRP holoenzyme contains at least 10 proteins, which, according to the results of two-hybrid studies (Houser-Scott et al. 2002), form an extensive network of interactions with each other, and some of these are expected to interact with RNA. It is possible that in the presence of other protein components, Pop6/7 may interact with additional regions of the RNA as well.

The P3 domain of the RNase MRP RNA has a homologous domain in the RNA component of RNase P (Fig. 4). Comparison of the P3 domains from S. cerevisiae RNase MRP and RNase P shows that several nucleotides are conserved. Indeed, a similar pattern of intraspecies conservation can be observed in other eukaryotes with the conserved nucleotides localized mostly to the internal loop of the domain (Ziehler et al. 2001; Li et al. 2002; Piccinelli et al. 2005). In addition, the P3 domains from S. cerevisiae RNase MRP and RNase P were shown to be interchangeable, suggesting similar role(s) in the two enzymes (Lindahl et al. 2000).

The similarity of the P3 domains in RNase MRP and RNase P suggests that binding of the Pop6/7 heterodimer to the P3 domain should not be limited to RNase MRP, but should be observed for the RNase P P3 domain as well. Gel mobility-shift experiments show that this is the case, and that the Pop6/7 heterodimer forms a 1:1 complex with the P3 domain of the RNase P RNA (Fig. 2B) similar to the P3 domain of the RNase MRP RNA. The binding constant for the interaction of the P3 domain of RNase P with the Pop6/7 heterodimer was estimated as 150 ± 60 nM in the presence of 100-fold excess of competing yeast tRNA, similar to the value obtained for the P3 domain of RNase MRP (140 ± 60 nM, above) (Fig. 2D).

The results of the footprint analysis show that binding of the Pop6/7 heterodimer to the RNase MRP RNA protects nucleotides 30–38 and results in hypersensitivity of nucleotides G49, U76, U77 (RNase V1), and U67 (RNase A) (Fig. 3). The protected nucleotides 30–38 belong to the lower strand of the internal loop of the P3 domain and the adjacent helical stem (Fig. 4C). Comparison of this region with the corresponding region of the P3 domain from S. cerevisiae RNase P shows conservation of the nucleotides of the internal loop (nucleotides 35–38 in RNase MRP and 38–41 in RNase P) with one additional nucleotide (U37) being added to the P3 loop of RNase P (Fig. 4). Similar conservation within an organism between P3 domains of RNases MRP and P can be observed for other yeast and metazoans (Ziehler et al. 2001; Piccinelli et al. 2005). Simultaneous mutation of the four nucleotides of the lower strand of the P3 loop that are protected by Pop6/7 binding (U35A, U36A, A37U, C38G) abolished protein binding to the P3 domain of RNase MRP (Fig. 2C). This result, combined with the conservation of those nucleotides, suggests that RNase MRP nucleotides 35–38 may be involved in a sequence-specific interaction with the Pop6/7 heterodimer. Alternatively, the Pop6/7 heterodimer may recognize a specific RNA folding motif and conservation of the nucleotides in the P3 loop may reflect sequence requirements for such a motif.

The intraspecies conservation of the P3 domains of RNases MRP and P in S. cerevisiae includes several nucleotides in the upper strand of the internal loop (nucleotides 65–66, 70–72 in RNase MRP) (Fig. 4). Binding of the Pop6/7 heterodimer did not protect this region, suggesting that the upper strand of the internal loop has essential function(s) other than binding of Pop6/7, and is possibly involved in interactions with other protein component(s). It is interesting to note that Pop6/7 binding results in increased sensitivity of U67 to RNase A (Fig. 3), indicating a change of the structure of the upper strand of the internal loop induced by binding of Pop6/7 to the lower strand of the loop. This change may, in principle, serve to prime the upper strand for interaction with other protein components such as Pop1 or Pop4 (Ziehler et al. 2001; Houser-Scott et al. 2002).

Pop6/7 heterodimer binding to RNase MRP RNA also results in protection of nucleotides 30–34 (Figs. 3, 4C). This double-helical region of the P3 domain is not conserved even when the P3 domains of RNases MRP and P from the same organism are compared, suggesting that the interaction of Pop6/7 with this region is not sequence specific. In principle, we cannot exclude that protection of nucleotides 30–34 of the double helix is not due to a direct protein–RNA interaction, but rather reflects steric inaccessibility of the nucleotides caused by the presence of a bulky Pop6/7 heterodimer in the immediate vicinity. However, this explanation seems to be unlikely, since Pop6/7 binding not only protects one of the strands of the helix, but also makes the other strand hypersensitive to RNase V1 (nucleotides U76, U77) (Fig. 3). Increased sensitivity of the other strand most likely indicates a change in the geometry of the helix upon Pop6/7 binding, which strongly suggests a direct RNA–protein interaction in this region. The presence of the non-sequence-specific component to the Pop6/7 binding to the P3 domain may potentially result in a weak binding to nonspecific RNAs. Overall, it is likely that interaction of Pop6/7 with the P3 domain involves both sequence- and structure-specific recognition. Elucidation of the exact details of the Pop6/7 interaction with the P3 domain will require crystallographic studies.

Mutational studies show that deletion of S. cerevisiae RNase MRP nucleotides 36–68 is lethal, while removal of the second stem of the P3 domain (nucleotides 45–64) results in a conditional phenotype (Shadel et al. 2000). Those observations are consistent with our results: removal of the Pop6/7 binding site in the Δ36–68 mutant should abolish Pop6/7 binding, resulting in a gross disruption of the enzyme structure, while removal of the second stem of the domain (nucleotides 45–64) could result in reduced protein binding due to a number of reasons, including distortion of the structure of the P3 internal loop.

Randomization of S. cerevisiae RNase P nucleotides U38, U39, C41, and A44 (which correspond to U35, U36, C38, and A41 in RNase MRP) showed that sequence deviations at those positions were unfavorable (Ziehler et al. 2001). The randomization results showed some degree of tolerance to single mutations in those positions, but multiple mutants were deleterious. The observed degree of tolerance likely reflects certain flexibility of the Pop6/7 binding to slight variations in RNA sequence or maintenance through cooperative binding with other protein components binding to other regions of the RNA. The results of three-hybrid studies indicated that the yeast protein component of RNase MRP/RNase P Pop1 was involved in a sequence-specific interaction with the conserved nucleotides of the P3 domain (Ziehler et al. 2001). Our results suggest that this interaction may involve Pop6/7 as an adapter, or be mediated by bridging through Pop6/7. Involvement of protein adapters or mediators in interaction of Pop1 with RNase MRP RNA has been previously suggested for the human enzyme (Pluk et al. 1999).

It was recently shown that the human protein subunits of RNases MRP and P, Rpp20, and Rpp25, form a stable heterodimer that binds the P3 domain of human RNase MRP (Pluk et al. 1999; Welting et al. 2007). Rpp20 is a human homolog of yeast Pop7 (Stolc et al. 1998). In addition, while the sequence similarity between Rpp25 and Pop6 is weak, computational analysis of homologs of these proteins from a number of different metazoan and fungal species has provided evidence for a potential relationship between metazoan Rpp25 and fungal Pop6 (Rosenblad et al. 2006). Taking that into account, it should be noted that the parallels between Rpp25/Rpp20 heterodimer in humans and Pop6/7 heterodimer in yeast are striking. These parallels possibly indicate a high degree of structural similarity between human and yeast RNases MRP/P with human Rpp25/Rpp20 playing the role of yeast Pop6/7. Indeed, three of the four proteins show homology with the Alba family of proteins involved in RNA metabolism and chromatin structure (Aravind et al. 2003). It is reasonable to assume that Pop6 will be found to have a similar fold.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Overexpression and purification of proteins

The plasmids pPop6 and pPop7 were constructed by inserting S. cerevisiae genes, Pop6 and Pop7, into the NdeI site of plasmid pET21b (Novagen). The genes were amplified from yeast genomic DNA by PCR with primers Pop6N (5′-TGATCAATGGCGTATATTAC-3′) and Pop6C (5′-TTATTGTTTGGTGAATGAATG-3′) for POP6, and Pop7NZ (5′-TGGCGCTGAAAAAAAACACCCACAACAAATCTACCAAACGAGTAACG-3′) and Pop7CZ (5′-TTAAACATAAATACGCAATTCTAC-3′) for Pop7. To facilitate expression in E. coli, silent mutations were introduced into the first eight codons of Pop7.

Plasmid p762 was made by inserting a fragment made by PCR using primers COEX5 (5′-GGTTGCGGATCCGTTTAACTTTAAGAAGGAGATATAC-3′) and POP6COEX3 (5′-CGGACAAAAGCTTTTATTGTTTGGTGAATGAATGTAGGTTTAAATC-3′), with plasmid pPop6 serving as a template, into BamHI/HindIII sites of plasmid pPop7. The resulting plasmid p762 had Pop6 gene inserted downstream of Pop7. Sequences of all plasmids were verified.

The proteins were expressed in Rosetta DE3 strain of E. coli (Novagen) at 28°C in LB medium, expression was induced by addition of IPTG to 1 mM at OD600 = 0.3, and the proteins were expressed for 3 h. For purification of the Pop6/7 complex, the cell pellets were harvested by centrifugation at 4°C, cells were resuspended in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 300 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF, and 1 mg/mL lysozyme. The suspension was incubated on ice for 60 min, then cells were disrupted by sonication. The lysate was cleared by centrifugation for 30 min at 17,000g. The cleared extract was treated with 0.1% polyethylenimine on ice and then centrifuged for 30 min at 17,000g at 4°C. The protein from the supernatant was precipitated with 70% ammonium sulfate overnight at 4°C. The precipitate was collected by centrifugation for 30 min at 17,000g (4°C), and dissolved in Buffer A (50 mM MES-NaOH at pH 6.0, 50 mM KCl, 5 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT, and 0.1 mM PMSF). The solution was loaded onto a pre-equilibrated SP-Sepharose column (Amersham). The protein was eluted from the column with a linear gradient of 0.1–0.5M NaCl in the starting buffer. Fractions containing the Pop6/7 complex were combined, diluted threefold with Buffer A, and loaded onto a Hi-Trap Heparin HP column (Amersham) pre-equilibrated with Buffer A. The Pop6/Pop7 complex was eluted with a linear gradient of 0.1–0.5M NaCl in the starting buffer, fractions of interest were combined, concentrated using an Amicon Ultra-15 concentrator (10,000 MWCO), and fractionalized through a Superdex 75 gel-filtration column (Amersham), which was pre-equilibrated with Buffer B (10 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.8, 400 mM NaCl, 50 mM KCl, 2 mM DTT). The fractions containing the purified Pop6/7 complex were pooled and concentrated with an Amicon Ultra-15 concentrator (10,000 MWCO). The procedure yielded about 4 mg of RNase-free Pop6/Pop7 complex per liter of culture.

The protocol for purification of Pop6 was similar, but instead of Buffer B, Buffer A supplemented with NaCl to 500 mM was used. The yield of Pop6 was about 8 mg/L of culture.

Protein concentrations were determined using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer; the extinction coefficients were calculated using ProtParam (ExPASy) (Gasteiger et al. 2005).

Estimation of Pop6:Pop7 molar ratio in the Pop6/7 complex

To estimate the molar ratio of Pop6 and Pop7 in the Pop6/7 complex, varying amounts of the complex (0.25–1.0 μg) were separated on a 15% denaturing SDS–polyacrylamide gel and stained with SYPRO Orange dye. The intensities of the bands were quantified using a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics). The relative intensities of the bands corresponding to Pop6 and Pop7 were normalized by the molecular weights of the proteins (18.2 kDa and 15.8 kDa, respectively), yielding a relative molar ratio. It should be noted that Pop7 is known to have anomalous mobility on SDS–polyacrylamide gels and actually migrates slower that Pop6 (Salinas et al. 2005).

In vitro transcription and RNA purification

The RNA components of yeast RNase MRP, RNase P, and P3 domains of RNases MRP and P were produced by in vitro transcription with T7 RNA polymerase (Milligan et al. 1987).

Plasmid p31/51 was used to produce the RNA component of RNase MRP. To make these plasmids, a fragment was generated by PCR with primers MRP31 (5′-GACGGGATCCTCGAGGTCTCTGGTGGGTCCATGGACCAAGAATAGTAAGCTC-3′) and MRP51 (5′-GCGGGATCCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGTCCATGACCAAAGAATCGTCAC-3′) using yeast genomic DNA as a template. The fragment was subsequently digested with BamHI and inserted into BamHI site of pUC19. To facilitate transcription, the first two 5′ nucleotides in RNase MRP RNA were replaced with GG and the compensatory mutations were introduced in the complementary segment of the P1 stem; the last five 3′ nucleotides (unpaired) were removed. The plasmid was linearized with BsaI and used as a template for in vitro transcription.

Plasmid pYRP was used to produce the RNA component of RNase P and was made in a similar fashion as p31/51, with primers YRP5 (5′-GCGGAATTCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGGAACAGTGGTAATTCCTACGATTAAG-3′) and YRP3N (5′-GACGGAATTCTCGAGGTCTCTGCGGGAACAGCAGCAGTAATCGGTATCG-3′), using the EcoRI site of pUC19. The three unpaired nucleotides at the 5′ and 3′ ends were removed, the first transcribed nucleotide was replaced with G, and the compensatory mutation was introduced at the complementary segment of the P1 stem. The plasmid was linearized with BsaI and used as a template for in vitro transcription.

Plasmid pP3A was used to produce the P3 domain of RNase MRP. To make this plasmid, a fragment was generated by PCR with primers P3A-5 (5′-GCGGGATCCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGTCGAAGCTTACAAAATGGAG-3′) and P3A-3 (5′-GACGGGATCCTCGAGGTCTCTGGCCAAAGCATATTACTGAGTA-3′) using plasmid p31/51 as a template, then the fragment was digested with BamHI and inserted into BamHI site of pUC19 plasmid. The plasmid was linearized with BsaI and used as a template for in vitro transcription.

Plasmid pP3P was used to produce the P3 domain of RNase P and was made similarly to the plasmid pP3A, but using primers P3P-5 (5′-GCGGAATTCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGACCTGTTTACAGAAGGATCC-3′), P3P-3 (5′-GACGGAATTCTCGAGGTCTCTGGACCTGATAATATCTGATAAC-3′), plasmid pYRP as a template, and EcoRI site of pUC19.

Plasmid pINV was used to produce control “antisense” RNase MRP RNA and was made in a way similar to the pP3A, but using primers MRP5A (5′-GCGGGATCCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGTCCATGGACCAAGAATAGTAAGCTCC-3′) and MRP3A (5′-GACGGGATCCGAATTCGGTCCATGACCAAAGAATCGTCAC-3′). The plasmid was linearized with EcoRI and used as a template for in vitro transcription. The transcription resulted in RNA complementary to the full-length RNase MRP RNA. Sequences of all plasmids were verified.

To produce the mutated (U35A, U36A, A37U, C38G) P3 domain of RNase MRP, oligonucleotides T7GG (5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGG-3′) and P3MUT1 (5′-GGAAGCATATTACTGAGTAAAAAAAATTTTACTCCATTTTCATTGCTTCCTATAGT GAGTCGTATTA-3′) were annealed in the presence of 10 mM NaCl by incubation at 85°C for 2 min followed by incubation on ice for 10 min and used as a template for run-off transcription.

To produce RNA, run-off transcription was performed using standard protocol (Milligan et al. 1987). The product of transcription was purified using 6% (for the whole length RNase MRP and RNase P RNAs and for the control “antisense” RNA) or 15% (for the separately produced P3 domains of RNase MRP and RNase P) denaturing polyacrylamide gels.

Footprint analysis

Gel-purified RNase MRP RNA was dephosphorylated with calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase and subsequently 5′-end labeled using [γ-32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase; labeled RNA was purified on a 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gel. Immediately before use, RNA was folded by incubation at 85°C for 2 min in 20 mM TrisHCl (pH 7.5), cooling to room temperature in a styrofoam rack, followed by incubation at 50°C for 10 min in the presence of 5 mM MgCl2, and subsequent cooling to room temperature in a styrofoam rack. This procedure was similar to that described in Walker and Avis (2004).

For footprint analysis, 1 pmol of labeled RNA was mixed with 9 pmol of unlabeled gel-purified RNase MRP RNA and subjected to folding as described above. To the folded RNA, KCl was added to 50 mM and RNA–protein complexes were formed by incubation of RNA with 10 pmol (1 μM) of Pop6/7 complex for 30 min at 30°C.

Partial digestion with RNases A and V1 was performed for 10 min at 0°C and 15 min at 30°C, correspondingly, using varying concentrations of the enzymes to make sure that the conditions when each RNA molecule is cut no more than once are achieved. Immediately following digestion, RNA was extracted with phenol/chloroform mix, precipitated with ethanol, and loaded on a 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gel with 8 M urea.

The reference ladders were produced by alkali hydrolysis in a buffer containing 5 mM glycine (pH 9.5), 2 mM MgSO4 (1 min at 95°C), and by digestion with RNase T1 (2 min at 65°C).

The radioactive bands were visualized with a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics).

Gel mobility-shift assays

To determine the stoichiometry of the Pop6/7–RNA complexes, the RNA of interest was folded as described above. RNA–protein complexes were formed by incubation of 2 μg of RNA (final concentration 2–15 μM) with corresponding amounts of protein for 30 min at 30°C in a binding buffer (BB) containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM KCl, and 5 mM MgCl2. Under those conditions, the concentrations of the components of the complex were at least by an order of magnitude higher than the binding constant for the complex (about 150 nM), thus allowing determination of the stoichiometry. The samples were loaded on a 4% native polyacrylamide gel and fractionated at 4°C. The gels were stained with Toluidine blue.

Filter-binding assay

RNase MRP RNA was 5′-end labeled, gel purified, and RNA–protein complexes were formed as described above with varying amounts of Pop6/7 complex. The final concentration of labeled RNA was 5 nM; the concentrations of Pop6/7 ranged from 50 to 800 nM. The complexes were filtered through a stack of BA83 Nitrocellulose (Whatman) followed by Hybond-N+ (Amersham) membranes. The membranes were washed with BB buffer (above) and dried. The intensities of the following spots were quantified using a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics): the intensity of a spot on the nitrocellulose membrane corresponded to the amount of loaded labeled RNA that formed complexes with proteins; the intensity of a spot on the Hybond-N+ membrane corresponded to the amount of loaded labeled RNA that did not form complex with Pop6/7; the sum of the intensities on the two membranes corresponded to the total amount of labeled RNA loaded. To quantify the proportion of RNA that formed complex with Pop6/7 under given concentration of the proteins, the intensity of a spot on the nitrocellulose membrane was normalized to the total intensity on the two membranes. To obtain an estimate of the binding constant, we used a single site binding model. The proportion of the RNA that formed complexes with Pop6/7 was plotted as a function of the Pop6/7 concentration, and the graph was interpolated to the point corresponding to 50%, which under conditions of the experiment (Pop6/7 was always present in high excess) corresponded to the binding constant. In the experiments with a competitor, 100-fold molar excess of unlabeled yeast tRNA was added to the labeled RNA prior to the formation of the RNA–protein complexes. The experiments were repeated three to five times and the average values of the binding constants were calculated.

Mass-spectrometry of Pop6 and Pop7

The identities of the proteins were confirmed by mass-spectrometry. The proteins were separated by SDS–polyacrylamide gel, visualized by Coomassie Blue staining, and the bands corresponding to the Pop6 and Pop7 were excised. The proteins were subjected to overnight in-gel digestion with sequencing grade trypsin. The samples were analyzed by a capillary liquid chromatography—tandem mass spectrometry system with a nanospray spray ionization source (capLC-nanoESI- MS/MS) that consisted of a Surveyor Micro AS autosampler, a Surveyor MS Pump, and an LTQ linear ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Electron Corporation). The digests were desalted on-line and eluted by using a 30-min linear acetonitrile gradient (2% to 40% acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid) at a flow rate of ∼0.3 μL/min obtained by precolumn splitting of a flow of 200 μL/min. The analytical column was a PicoFrit column (New Objective) packed in-house with 5 μm wide pore C18 particles (Supelco Co.). Tandem MS (collision-induced dissociation) was triggered for the five most intense precursor ions (above an intensity threshold of 1000 counts) from survey scans performed over m/z 550–1500. XCalibur data were converted to .dta files using extract_msn software from the manufacturer. The resulting .dta files were merged and searched against Swiss-Prot protein database using a locally maintained MASCOT search engine (version 2.2). Database searching of the MS/MS spectra against Swiss-Prot protein database resulted in unambiguous identification of Pop6 and Pop7 with the detection of seven and 10 peptides, respectively.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Paul Babitzke, Phil Bevilacqua, and Helen Yakhnin for helpful suggestions. This work was supported in part by an American Heart Association National Scientist Development Grant to A.S.K. and by grant GM063798 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences to M.E.S.

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.654407.

REFERENCES

- Altman, S., Kirsebom, L. Ribonuclease P. In: Gesteland R.F., et al., editors. The RNA world. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1999. pp. 351–380. [Google Scholar]

- Aravind, L., Iyer, L.M., Anantharaman, V. The two faces of Alba: The evolutionary connection between proteins participating in chromatin structure and RNA metabolism. Genome Biol. 2003;4:R64. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-10-r64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain, J.R., Lee, Y., Lane, W.S., Engelke, D.R. Purification and characterization of the nuclear RNase P holoenzyme complex reveals extensive subunit overlap with RNase MRP. Genes & Dev. 1998;12:1678–1690. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.11.1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, D.D., Clayton, D.A. A novel endoribonuclease cleaves at a priming site of mouse mitochondrial DNA replication. EMBO J. 1987;6:409–417. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb04770.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster, A.C., Altman, S. Similar cage-shaped structures for the RNA components of all Ribonuclease P and Ribonuclease MRP enzymes. Cell. 1990;62:407–409. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90003-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank, D.N., Pace, N.R. Ribonuclease P: Unity and diversity in a tRNA processing ribozyme. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1998;67:153–180. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank, D.N., Adamidi, C., Ehringer, M.A., Pitulle, C., Pace, N.R. Phylogenetic-comparative analysis of the eukaryal ribonuclease P RNA. RNA. 2000;6:1895–1904. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200001461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasteiger, E., Hoogland, C., Gattiker, A., Duvaud, S., Wilkins, M.R., Appel, R.D., Bairoch, A. Protein identification and analysis tools on the ExPASy server. In: Walker J.M., editor. Proteomics protocols handbook. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ: 2005. pp. 571–607. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, T., Cai, T., Aulds, J., Wierzbicki, S., Schmitt, M.E. RNase MRP cleaves the CLB2 mRNA to promote cell cycle progression: Novel method of mRNA degradation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:945–953. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.3.945-953.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houser-Scott, F., Xiao, S., Millikin, C.E., Zengel, J.M., Lindahl, L., Engelke, D.R. Interactions among the protein and RNA subunits of Saccharomyces cerevisiae nuclear RNase P. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2002;99:2684–2689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052586299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karwan, R., Bennett, J.L., Clayton, D.A. Nuclear RNase MRP processes RNA at multiple discrete sites—Interaction with an upstream G-box is required for subsequent downstream cleavages. Genes & Dev. 1991;5:1264–1276. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.7.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikovska, E., Svard, S.G., Kirsebom, L.A. Eukaryotic RNase P RNA mediates cleavage in the absence of protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2007;104:2062–2067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607326104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, X., Frank, D.N., Pace, N., Zengel, J.M., Lindahl, L. Phylogenetic analysis of the structure of RNase MRP in yeast. RNA. 2002;8:740–751. doi: 10.1017/s1355838202022082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl, L., Fretz, S., Epps, N., Zengel, J.M. Functional equivalence of hairpins in the RNA subunits of RNase MRP and RNase P in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . RNA. 2000;6:653–658. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200992574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lygerou, Z., Allmang, C., Tollervey, D., Seraphin, B. Accurate processing of a eukaryotic precursor ribosomal RNA by Ribonuclease MRP in vitro. Science. 1996;272:268–270. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5259.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquez, S.M., Chen, J.L., Evans, D., Pace, N.R. Structure and function of eukaryotic Ribonuclease P RNA. Mol. Cell. 2006;24:445–456. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan, J.F., Groebe, D.R., Witherell, G.W., Uhlenbeck, O.C. Oligoribonucleotide synthesis using T7 RNA-polymerase and synthetic DNA templates. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:8783–8798. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.21.8783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccinelli, P., Rosenblad, M.A., Samuelsson, T. Identification and analysis of ribonuclease P and MRP RNA in a broad range of eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:4485–4495. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluk, H., van Eenennaam, H., Rutjes, S.A., Pruijn, G.J.M., van Venrooij, W.J. RNA–protein interactions in the human RNase MRP ribonucleoprotein complex. RNA. 1999;5:512–524. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299982079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblad, M.A., Lopez, M.D., Piccinelli, P., Samuelsson, T. Inventory and analysis of the protein subunits of the ribonucleases P and MRP provides further evidence of homology between the yeast and human enzymes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:5145–5156. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salinas, K., Wierzbicki, S., Zhou, L., Schmitt, M.E. Characterization and purification of Saccharomyces cerevisiae RNase MRP reveals a new unique protein component. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:11352–11360. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409568200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, M.E., Clayton, D.A. Nuclear RNase MRP is required for correct processing of pre-5.8S ribosomal RNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Mol. Cell. Biol. 1993;13:7935–7941. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.12.7935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, M.E., Clayton, D.A. Characterization of a unique protein component of yeast RNase MRP—An RNA binding protein with a zinc-cluster domain. Genes & Dev. 1994;8:2617–2628. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.21.2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadel, G.S., Buckenmeyer, G.A., Clayton, D.A., Schmitt, M.E. Mutational analysis of the RNA component of Saccharomyces cerevisiae RNase MRP reveals distinct nuclear phenotypes. Gene. 2000;245:175–184. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolc, V., Katz, A., Altman, S. Rpp2, an essential protein subunit of nuclear RNase P, is required for processing of precursor tRNAs and 35S precursor rRNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1998;95:6716–6721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker, S.C., Avis, J.M. A conserved element in the yeast RNase MRP RNA subunit can participate in a long-range base-pairing interaction. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;341:375–388. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker, S.C., Engelke, D.R. Ribonuclease P: The evolution of an ancient RNA enzyme. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2006;41:77–102. doi: 10.1080/10409230600602634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welting, T.G.M., Peters, F.M.A., Hensen, S.M.M., van Doorn, N.L., Kikkert, B.J., Raats, J.M.H., van Venrooij, W.J., Pruijn, G.J.M. Heterodimerization regulates RNase MRP/RNase P association, localization, and expression of Rpp20 and Rpp25. RNA. 2007;13:65–75. doi: 10.1261/rna.237807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziehler, W.A., Morris, J., Scott, F.H., Millikin, C., Engelke, D.R. An essential protein-binding domain of nuclear RNase P RNA. RNA. 2001;7:565–575. doi: 10.1017/s1355838201001996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]