Abstract

Purpose

To investigate whether and how the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) gene cNSCL2 is involved in retinal development.

Methods

cNSCL2, the chick homologue of human NSCL2, was isolated and sequenced. In situ hybridization was used to examine its spatial and temporal expression pattern in the retina. Replication-competent retrovirus RCAS was used to drive cNSCL2 misexpression in the developing chick retina, and the effect of the misexpression was analyzed.

Results

Expression of cNSCL2 in the retina was restricted. Its mRNA was detected in amacrine and horizontal cells, but not in photoreceptor, bipolar, or ganglion cells. Retroviral-driven misexpression of cNSCL2 in the developing chick retina resulted in missing photoreceptor cells and gross deficits in the outer nuclear layer (ONL). These deficits were probably not because of decreased photoreceptor production, in that the ONL appeared normal in early developmental stages. TUNEL+ cells were detected in the ONL, indicating that photoreceptor cells underwent apoptosis in retinas misexpressing cNSCL2. Müller glial cells were far fewer in the experimental retina than in the control, indicating that cNSCL2 also caused Müller glia atrophy. The onset of Müller glia disappearance preceded that of photoreceptor degeneration.

Conclusions

Expression of cNSCL2 in the chick retina was restricted to amacrine and horizontal cells. Misexpression of cNSCL2 caused severe retinal degeneration, and photoreceptor cells and Müller glia were particularly affected.

The vertebrate retina contains six major types of cells: photoreceptors, horizontal cells, bipolar cells, amacrine cells, ganglion cells, and Müller glia. These cells are stereotypically organized into three nuclear layers separated by two synaptic layers. During retinal neurogenesis, precursors of each cell type migrate to their prospective location and undergo a unique differentiation program, enabling them to assume a distinct morphology and to perform a discrete function. The molecular mechanism underlying retinal development is not fully understood.

The Drosophila proneural genes, achaete-scute complex and atonal, encode the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) family of transcription factors and play important roles in neurogenesis in the fly. In vertebrates, a number of homologues have been identified and shown to play important roles in nervous system development.1 In the developing retina, mash-1/cash-1, ngn1, math-5/cath5, and math3/cath3 are expressed in progenitor cells.2–9 math3/cath3 is also expressed in bipolar cells.10,11 Various spatial patterns of neuroD expression have been reported.7,8,11–15 Significant progress has been made in understanding how these proneural genes function during retinal neurogenesis. Mice without mash-1 do not exhibit any obvious abnormalities in eye development during embryogenesis and at birth, the time when the mutant mice die,16,17 but explant cultures of mash-1−/− retinas showed a delay in differentiation of rod photoreceptors, horizontal cells, and bipolar cells; a decrease in bipolar cell number, and an increase in glia.17 Retinal explant cultures were also used to examine retinal phenotype of neuroD null mutation, and it is reported that mouse neuroD plays multiple roles during retinal development.15 Studies from our laboratory indicated that chick neuroD is involved in specifying a photoreceptor cell fate.14,18,19 Misexpression of neuroD in the developing chick retina results in an overproduction of photoreceptor cells specifically, and ectopic neuroD expression in cultured RPE cells promotes de novo generation of photoreceptor cells selectively.14,18,19

NSCL is a two-member subfamily of bHLH genes homologous to Drosophila proneural gene atonal. Mammalian NSCL1 and NSCL2 were originally cloned by low-stringency hybridization.20,21 Northern blot analysis and in situ hybridization revealed that expression of mammalian NSCL1 and NSCL2 is specific to neural tissues.20–22 DNA microarray analysis has identified NSCL2 as a target of p53.23 Targeted deletion of NSCL2 has been reported to result in a disruption of the hypothalamic–pituitary axis and triggers adult-onset obesity in mice.24 The expression and function of mammalian NSCL1 and NSCL2 in retinal development remain to be studied.

cNSCL1 is the chick homologue of mammalian NSCL1 and, similar to its mammalian counterpart, appears specific to neural tissues.25 In the developing retina, cNSCL1 is expressed transiently in the developing ganglion cells and later in Müller glia.26 Misexpression of cNSCL1 decreases cell proliferation activity in the retina and in the external granular layer of the developing cerebellum,25,26 suggesting that one function of cNSCL1 may be to prevent postmitotic cells from reentering the cell cycle.

To learn whether and how NSCL2 is involved in retinal development, we cloned its chick homologue, cNSCL2, examined its expression pattern in the retina, and studied the effect of its misexpression on retinal development. We found that cNSCL2 was expressed in amacrine and bipolar cells. Misexpression of cNSCL2 in the developing retina resulted in retinal degeneration with profound atrophy of photoreceptors and glia.

Methods

Cloning of cNSCL2

We probed an E8 brain cDNA library27 with human NSCL1.20,21 Among the positive clones, two were highly homologous to the human NSCL2 sequence21,22 and were named cNSCL2 (GenBank accession number AF109012). (GenBank is provided in the public domain by the National Center for Biotechnology Information and is available at http://www.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/.) The same library was probed using cNSCL2. Among the 28 clones isolated, 18 contained the cNSCL2 sequence.

In Situ Hybridization

Digoxigenin-labeled antisense RNA probes were synthesized from template DNA that contained approximately 1 kb of the 3′ untranslated sequence and 138 bases of the 3′ coding sequence (corresponding to the C′ terminal 46 amino acids). In situ hybridization was performed on retinal cryosections as previously described.26

Generating RCAS-cNSCL2 Retrovirus

The coding sequence of cNSCL2, along with 27 bases of the 5′ untranslated region and 860 bases of the 3′ untranslated region, was digested out of a cDNA clone with SmaI and XhoI. The DNA fragment was inserted into shuttle vector ClaI2Nco. A ClaI cassette was then generated and placed into RCAS, a replication-competent retrovirus.28 Transfection with the recombinant proviral DNA and production of viral stock were as described.14 The control virus expressing green fluorescent protein (GTP) was generated previously.14

Microinjection of RCAS-cNSCL2

Retrovirus RCAS-cNSCL2, or RCAS-GFP, was microinjected into the neural tube and the subretinal space at E2, stage 15 to 17, as previously described.14 Retinas were harvested at different developmental stages and analyzed histologically in combination with immunostaining and in situ hybridization.

Immunohistochemical Analyses

Standard procedures of immunocytochemistry were used. Anti-LIM (4F2, 1:50), anti-AP2 (3B5, 1:50), and anti-vimentin (H5, 1:1000; or AMF-17b, 1:500) were obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (Iowa University, Iowa City). Polyclonal anti-AP2 antibody (1:500) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz). Monoclonal antibody against Brn3a (1:200) was purchased from Chemicon (Temecula, CA). Pulse-labeling chick embryos with bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) and detection of BrdU incorporation were performed as previously described.26

Detection of Apoptotic Cells

The presence of apoptotic cells in cryosections of the developing retina was examined by the TUNEL method using a cell death detection kit (In Situ Cell Death Detection; Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Results

Sequence of cNSCL2

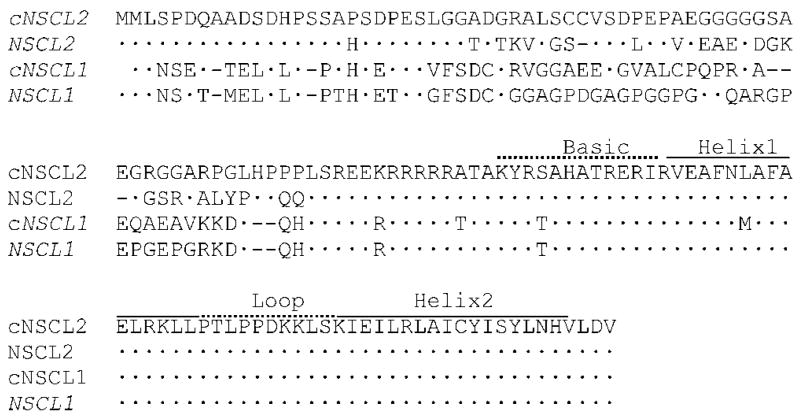

Library screening identified a bHLH gene encoding a protein of 137 amino acids. The bHLH domain of the isolated sequence was 100% identical with that of human NSCL2, and the overall sequence identity between them was 81% (Fig. 1). We therefore referred to this gene as cNSCL2, the chick homologue of mammalian NSCL2. The bHLH domain of cNSCL2 is 95% identical with that of cNSCL1, with 61% overall sequence identity (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequence of cNSCL2 with that of human NSCL2 and NSCL1 and chick cNSCL1. Identical residues are indicated by dots. Gaps, represented by hyphens, were introduced to maximize homology. The bHLH region is marked.

Expression Pattern of cNSCL2

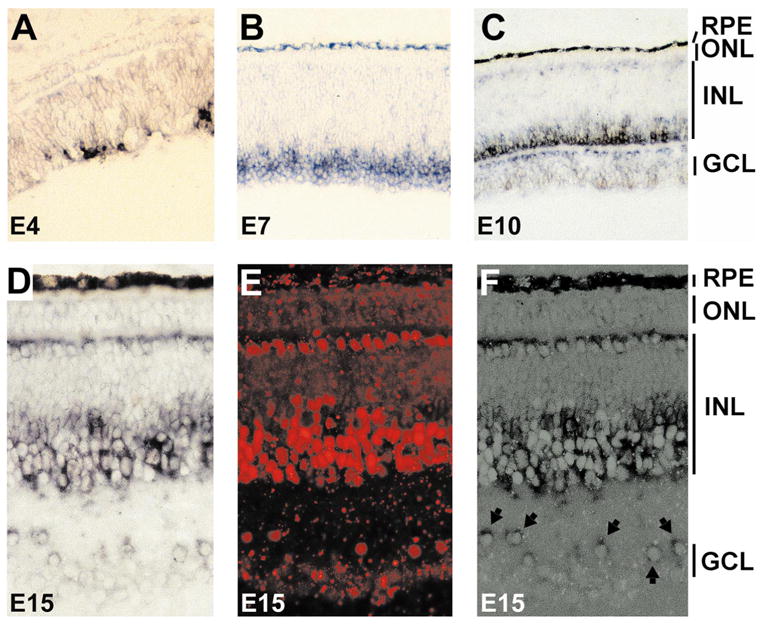

We examined cNSCL2 expression in the retina using in situ hybridization with digoxigenin-labeled antisense RNA probes. At embryonic day (E)4, cNSCL2 was already expressed (Fig. 2A) in the central region, which is developmentally more advanced than the peripheral retina. As development progressed, more cells expressed cNSCL2, and by E7 (Fig. 2B) most cNSCL2+ cells were aligned adjacent to young ganglion cells that occupy the innermost portion of the retinal neuroepithelium. This spatial pattern suggested that cNSCL2 was being expressed in young amacrine cells. At E10, when the demarcation of the three nuclear layers is conspicuous, cNSCL2 mRNA was detected in cells in the inner portion of the inner nuclear layer (INL) immediately above the inner plexiform layer (IPL; Fig. 2C). This anatomic location is typical for amacrine cells. Displaced amacrine cells residing in the IPL also expressed cNSCL2. Weak expression was detected in horizontal cells immediately beneath the outer plexiform layer (OPL). Expression of cNSCL2 in both horizontal cells and amacrine cells persisted throughout late retinal development (Fig. 2D) and in the mature retina (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Spatial-temporal pattern of cNSCL2 expression in the developing retina. (A–C) Cryosections of chick retinas at E4 (A), E7 (B), and E10 (C) hybridized with digoxigenin-labeled antisense RNA probes against cNSCL2. (D–F) Double labeling of E15 retina with anti-cNSCL2 RNA probes and anti-AP2 antibodies. (D) View of cNSCL2 mRNA-positive cells; (E) view of AP2+ cells with epifluorescence; (F) simultaneous view of both cNSCL2 mRNA+ cells and AP2+ cells demonstrates a colocalization of the two markers. Arrows: double-labeled, displaced amacrine cells (F). Magnification, (A–C) ×50; (D–F) × 100.

In the chick retina, amacrine and horizontal cells express anti-AP2 immunoreactivity.29 To determine whether cNSCL2 mRNA and AP2 immunoreactivity were colocalized, we performed double-labeling experiments of in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry. The in situ hybridization and immunostaining labeled the same cells, indicating that cells expressing cNSCL2 were also immunopositive for AP2 (Figs. 2D–F). Double labeling was observed in both horizontal cells and amacrine cells, including displaced amacrine cells (Fig. 2F, arrows).

Photoreceptor Deficits in Retinas Misexpressing cNSCL2

To study the role of cNSCL2 in retinal development, its coding sequence was inserted into RCAS to achieve cNSCL2 misexpression in retinal cells under viral control. A retroviral suspension of RCAS-cNSCL2, or RCAS-GFP as a control, was microinjected into the subretinal space and the neural tube of chick embryos at E2. Because the retrovirus is replication competent, its administration into embryos at an early developmental stage resulted in widespread viral infection both within and outside the central nervous system.30 Grossly, embryos infected with RCAS-cNSCL2 developed normally, and their eye sizes appeared indistinguishable from those of the control. This is in contrast to the misexpression of cNSCL1. RCAS-cNSCL1 embryos die midway through gestation and exhibit severe developmental abnormalities including small eyes, an enlarged and exposed tectum, and retarded limb.25,26,30

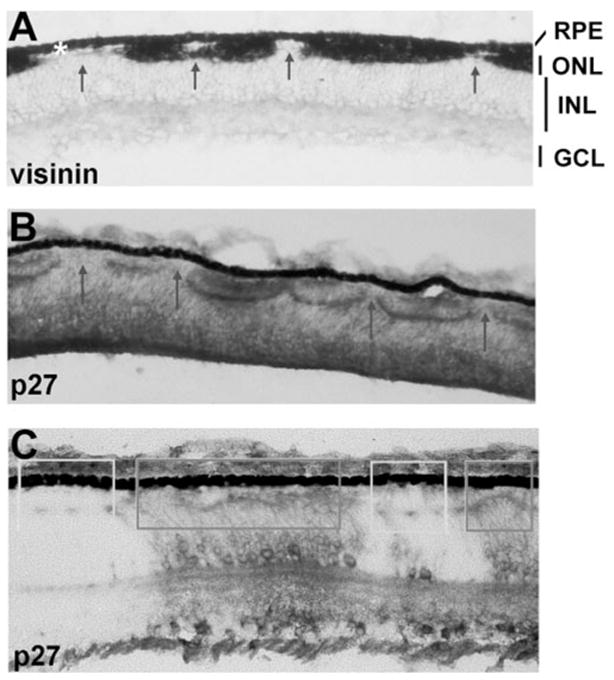

Histologic analyses of RCAS-cNSCL2 retinas at E12 and beyond, however, revealed severe photoreceptor deficits and gross alterations of the structure of the outer nuclear layer (ONL). In normal chick retina, the ONL is a continuous structure consisting of both cones and rods, with the majority being cones that express visinin. In the experimental retina, however, the ONL became fragmented with photoreceptorless regions interrupting the normal-looking patches (Figs. 3A, 3B). Staining a partially infected retina with a specific antibody against viral protein p27 showed that the ONL was specifically abnormal in those regions where the retrovirus was present (Fig. 3C, dark boxes), whereas the ONL in the adjacent, uninfected regions appeared normal (Fig. 3C, light boxes). Thus, the photoreceptor paucity was directly related to cNSCL2 misexpression in the region.

Figure 3.

Photoreceptor deficits in E12 retinas misexpressing cNSCL2. (A) Distribution of cone photoreceptor cells revealed with in situ hybridization using digoxigenin-labeled antisense RNA probes against visinin. Visinin+ cells were not continuous, but interrupted by photoreceptorless regions (arrows). No gross disruptions of the GCL and INL were apparent. White asterisk: RPE. (B, C) Immunostaining with a specific antibody against p27, a viral protein. Thorough infection resulted in interruption of the ONL (arrows in B), and partial infection produced a milder distortion of the ONL (C). Distortion of the ONL was apparent only in infected regions (dark boxes). In the adjacent, uninfected regions, the ONL appeared normal (light boxes). Magnifications, ×50.

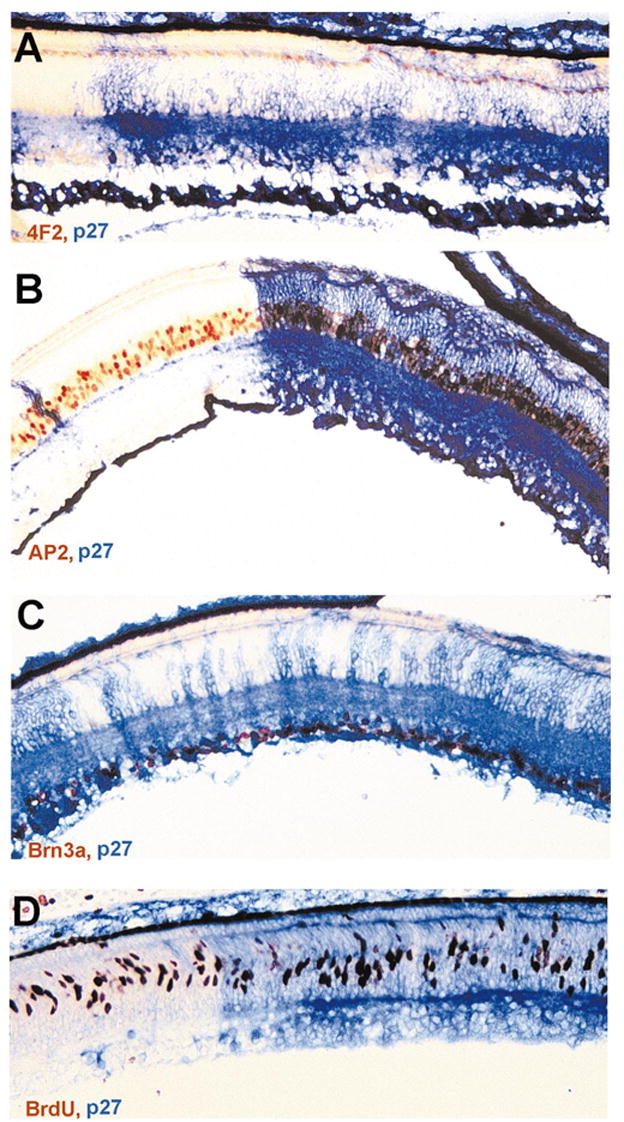

In contrast to the gross ONL alteration, the ganglion cell layer (GCL) and the INL appeared normal with the exception of INL cells filling the gaps in the ONL. Cells intervening in the ONL expressed bipolar cell marker chx10 (Fig. 4) and horizontal cell marker 4F2+ (Fig. 5A), demonstrating that these INL cells filled in the gaps left by photoreceptor deficits in the ONL. To examine whether there were apparent deficiencies in the INL neurons and in GCL neurons, E12 retinas misexpressing cNSCL2 were labeled with various markers that identify the different types of nonphotoreceptor neurons. Horizontal cells were identified with a monoclonal antibody 4F2, which recognizes the LIM protein.31 Bipolar cells were marked by in situ hybridization for chx10 mRNA,32 amacrine cells with monoclonal antibody against AP2, and ganglion cells with monoclonal antibody against Brn3a.33 Sections were then double-labeled with anti-p27 antibody to highlight areas infected with RCAS-cNSCL2. No obvious deficits were observed in the number of horizontal cells (Fig. 5A), bipolar cells (Fig. 4), amacrine cells (Fig. 5B), and ganglion cells (Fig. 5C) in infected regions compared with adjacent, uninfected regions. Retinal cell proliferation was examined with BrdU incorporation, and no difference in the number of BrdU+ cells was observed between the infected regions and the adjacent, uninfected regions (Fig. 5D).

Figure 4.

Presence of bipolar cells in the photoreceptorless regions of the ONL in E12 retinas misexpressing cNSCL2. Bipolar cells were identified by in situ hybridization with an antisense RNA probe against chx10. (A) A control retina infected with RCAS-GFP. (B) A retina infected with RCAS-cNSCL2. Magnifications, ×50.

Figure 5.

Various types of nonphotoreceptor neurons in an E12 retina and BrdU+ cells in an E9 retina partially infected with RCAS-cNSCL2. (A) A single layer of horizontal cells (4F2+/LIM+, in red) both in infected (blue) and uninfected regions. (B) Amacrine cells, marked by AP2 immunoreactivity (red), in infected (blue) and uninfected regions. (C) Ganglion cells, identified with Brn3a expression (red or dark), in infected and uninfected regions. (D) BrdU+ cells (red) in infected and uninfected regions in an E9 retina. Magnifications, ×50.

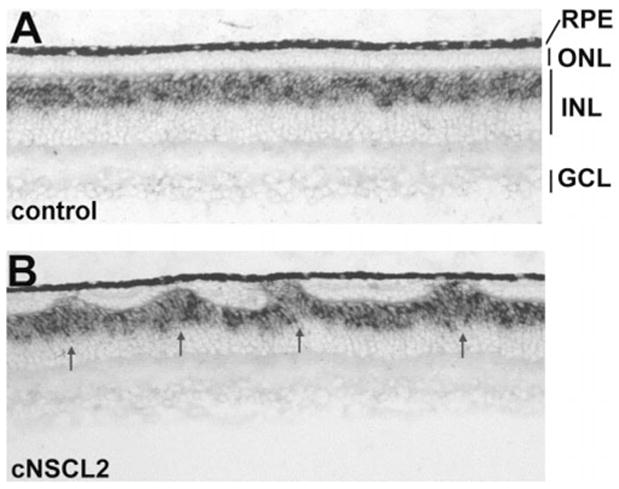

Photoreceptor Degeneration in Retinas Misexpressing cNSCL2

To determine whether the photoreceptor deficits in retinas misexpressing cNSCL2 were caused by reduced photoreceptor production or by photoreceptor degeneration subsequent to photoreceptor genesis, retinas infected with RCAS-cNSCL2 were examined at early developmental stages. Up to E9, these retinas appeared normal, and the number of visinin+ cells and the thickness of the ONL were indistinguishable from the control (Fig. 6A; data not shown).

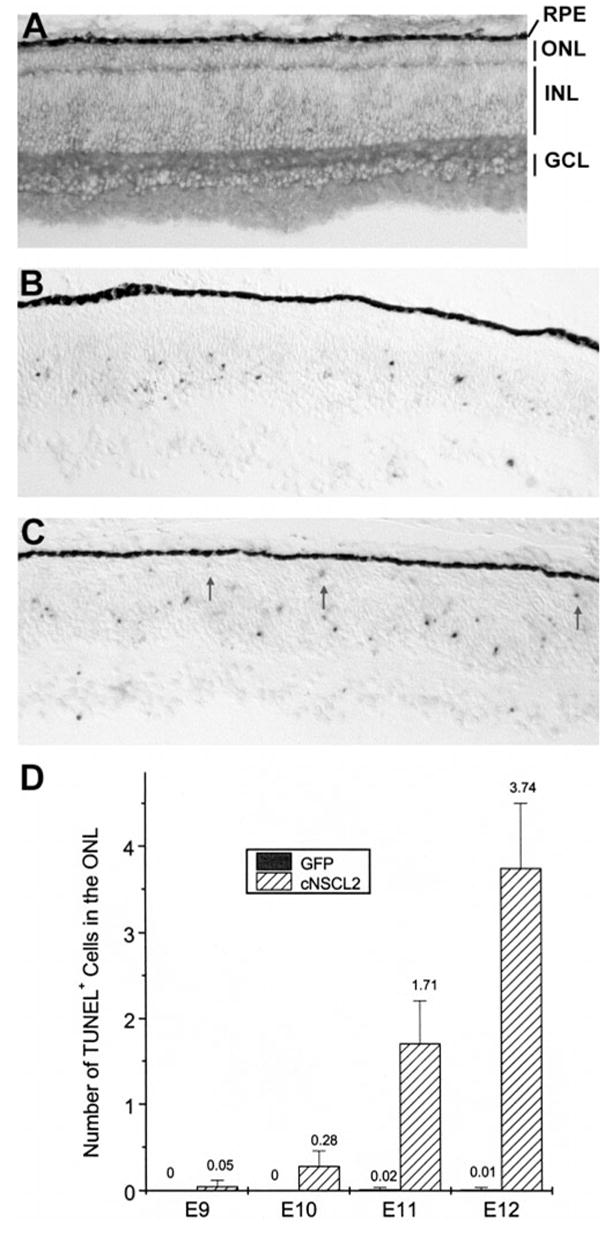

Figure 6.

Photoreceptor degeneration in retinas misexpressing cNSCL2. (A) Anti-P27 immunohistochemistry of an E9 retina infected with RCAS-cNSCL2. The ONL appeared normal. (B, C) TUNEL+ cells in E11 retinas infected with RCAS-GFP (B) or RCAS-cNSCL2 (C). TUNEL+ cells were absent in the ONL of the control (B) but were present in experimental retina (C, arrows). (D) Quantification of TUNEL+ cells in the ONL of RCAS-cNSCL2, or RCAS-GFP, retinas at different developmental stages. Shown are means ± SD of TUNEL+ cells per view area under a ×20 objective. Each data point represents three retinas with more than 20 view areas scored in each retina.

Since chick photoreceptor cells are generated between E6 to E7, the normal appearance of these retinas up to E9 indicated that the genesis of photoreceptor cells was not affected by cNSCL2 misexpression. Therefore, the photoreceptor deficiency observed at a later stage (i.e., E12) was probably due to degeneration of young photoreceptor cells. This possibility was tested with a TUNEL assay. In the control retina infected with RCAS-GFP retrovirus, TUNEL+ cells were present in the GCL and the INL, but were absent in the ONL (Fig. 6B). These data are consistent with the published observation that developing photoreceptor cells in the chick retina do not undergo apoptosis.34 In RCAS-cNSCL2 retinas, TUNEL+ cells were detected in the ONL (Fig. 6C, arrows), in addition to the GCL and the INL. Starting from E10, the number of TUNEL+ cells dramatically increased over the next 2 days (Fig. 6D). These results indicate that the disintegration of the ONL in RCAS-cNSCL2 retinas resulted from degeneration of young photoreceptor cells.

Glial Cell Atrophy in cNSCL2 Retinas

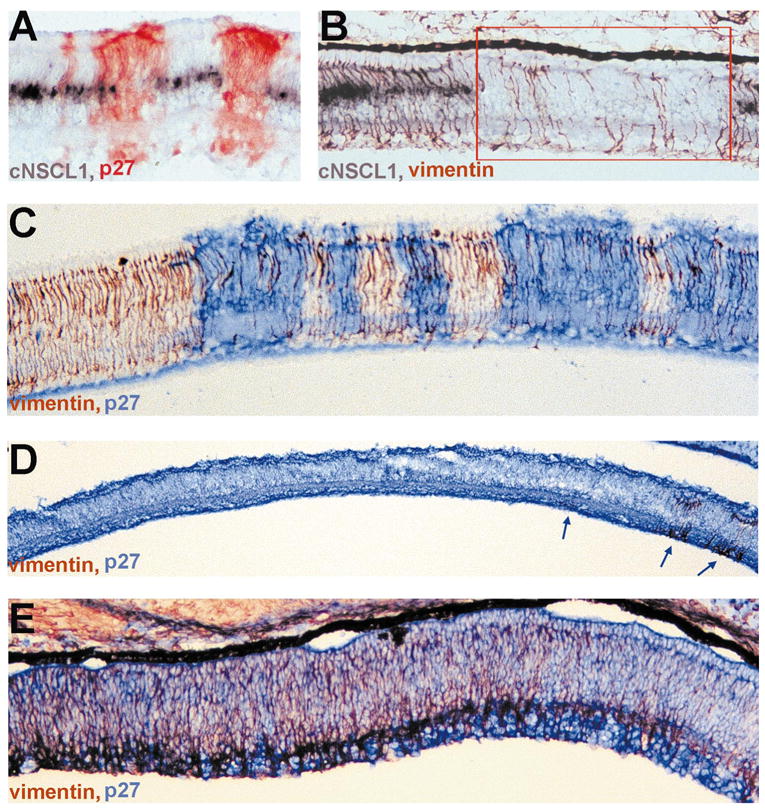

Müller cells are the major glial component of the retina and are the last group of cells born during retinal neurogenesis. In the chick retina, glial genesis takes place on E8 in the central retina. Müller cells extend across nearly the entire radial length of the retina. Their somas reside in the middle of the INL and their processes reach and form the external and inner limiting membranes. Developing Müller glia can be identified by the expression of vimentin,35 cNSCL1,26 and glutamine synthetase.36 In retinas partially infected with RCAS-cNSCL2, cNSCL1 expression was detected in uninfected regions, but not in infected regions (Figs. 7A, 7B). Double labeling showed that vimentin+ cells were scarce in regions where no cNSCL1 expression was detected (Fig. 7B). Reduction in vimentin+ cell number was apparent only in regions infected with RCAS-cNSCL2 (Fig. 7C). Expression of glutamine synthetase was also specifically absent in regions infected with RCAS-cNSCL2 (data not shown).

Figure 7.

Reduction of Müller glia cell number in retinas infected with RCAS-cNSCL2. (A) Double labeling with antisense RNA probes against cNSCL1 (purple) and anti-p27 antibody (red) in a partially infected E12 retina. In uninfected regions, cNSCL1 mRNA was present in Müller glia located in the middle of the INL. In the infected region, however, no cNSCL1+ cells were present. (B) Double labeling with antisense RNA probes against cNSCL1 (purple) and anti-vimentin antibody (red/brown) in a partially infected E12 retina. When cNSCL1+ cells were absent, the number of vimentin+ cells was conspicuously reduced (red box). (C) Double-labeling for vimentin (red/brown) and p27 (blue) in a partially infected E12 retina. Note that the number of vimentin+ cells was specifically decreased in regions infected with RACS-cNSCL2. (D) Double-labeling for vimentin (red/brown) and p27 (blue) in a thoroughly infected E12 retina, showing that by E12 vimentin+ cells was essentially gone, except in a few places (arrows). (E) Double-labeling for vimentin (red) and p27 (blue) of an E9 retina. At this early stage of development, vimentin+ cells were abundantly present in the peripheral retina (left). Note, however, that their number decreased toward the central retina (right), the development of which was more advanced than the peripheral retina. Magnifications, (A–C) ×50; (D) ×25; (E) ×50.

In a thoroughly infected E12 retina, vimentin+ cells were scarce and were detected in only a few places (Fig. 7D, arrows). However, at early developmental stages, such as E9, a large number of vimentin+ cells were present in the peripheral region, where development lags behind the central region. Remarkably, in the same section there were far fewer vimentin+ cells on the central side than on the peripheral side (Fig. 7E). This suggested that glial cells were generated, but the young glial cells disappeared soon after their birth. The significant reduction in the number of vimentin+ cells in central retina at E9 indicated that Müller glial disappearance preceded photoreceptor degeneration.

Discussion

Two members of the cNSCL subfamily of bHLH genes are expressed in the chick retina but have very different expression profiles. cNSCL1 is expressed first transiently in young ganglion cells and then persistently in glial cells.26 However, cNSCL2 mRNA was detected in amacrine and horizontal cells in both developing and adult retina. The distinct expression patterns of the two related genes imply that they play different roles in retinal development, and illustrate that our antisense RNA probes were specific to each gene.

Retroviral-driven misexpression of cNSCL1 is lethal to the embryo and causes gross developmental abnormalities. In contrast, misexpression of cNSCL2 in chick embryos was tolerated, and the gross appearance of experimental embryos was indistinguishable from the control. Misexpression of cNSCL1 in the developing retina results in small eye, whereas reduction of eye size was not observed with cNSCL2 misexpression. At the microscopic level, cNSCL1 misexpression results in INL disorganization,26 but cNSCL2 misexpression caused ONL disintegration. Apparently, cNSCL1 and cNSCL2 have dissimilar functions in retinal development, even though they belong to the same subfamily and their bHLH domains are 95% identical.

Some proneural genes are involved in neural cell fate specification, but cNSCL2 is unlikely to play a key role in the specification of amacrine and horizontal cell fates. At least it is not sufficient to instruct a progenitor cell to adopt such cell fates. Misexpression of cNSCL2 in the developing chick retina did not increase the number of AP2+ cells (amacrine cells) or horizontal cells (AP2+ or LIM+). The persistent expression of cNSCL2 in adult retina suggests that it may regulate the expression of genes that are involved in the maintenance or function of horizontal and amacrine cells.

The distortion of the ONL in retinas misexpressing cNSCL2 was marked by the absence of photoreceptor cells. The TUNEL assay revealed that young photoreceptor cells underwent apoptosis. Before E10, the number of TUNEL+ cells remained low, and the ONL appeared normal. Thus, misexpression of cNSCL2 in the developing retina interfered with the survival of photoreceptor cells and caused them to degenerate but had no effect on photoreceptor genesis.

Analyses with markers that identify different types of retinal neurons showed that there were no apparent deficits in the numbers of horizontal, bipolar, amacrine, and ganglion cells in retinas misexpressing cNSCL2. However, the three Müller glial markers, vimentin, cNSCL1, and glutamine synthetase, were either absent or were present in an extremely small number of cells. Vimentin+ cells were present in abundance at early developmental stages, but their number decreased as development proceeded, indicating that glial cells were produced under cNSCL2 misexpression. Examining cell proliferation with BrdU incorporation showed no difference in the number of BrdU+ cells between the experimental retina and the control. Taken together, these observations suggest that cNSCL2 misexpression causes young glial cells to disappear or to degenerate. However, it was difficult to pinpoint whether glial cells underwent apoptosis. Müller glia account for only 1 of the 14 tiers of the INL cells in the chick retina, and some INL cells undergo programmed cell death during normal development.

A decrease in glial cell number was observed before the reduction in photoreceptor cell number was noticeable. This raises the question of whether photoreceptor degeneration was secondary to glial degeneration. The idea that glia provides nourishment to photoreceptor cells has been in the literature for a long time, but solid data supporting the notion are scarce. Recent studies show that glial cells may mediate bFGF’s effect on promoting photoreceptor cell survival.37 However, it is also possible that degeneration of photoreceptor cells and glial cells are independent events from cNSCL2 misexpression. Although proneural bHLH genes are known to block gliogenesis, the dramatic reduction in glial cell number in E12 retinas was unlikely due to cNSCL2 blocking gliogenesis, because a large number of glial cells were detected at earlier stages.

It is unclear by what mechanisms cNSCL2 causes glial and photoreceptor cells to degenerate. Photoreceptor and glial cells normally do not express cNSCL2. One scenario is that ectopic cNSCL2 expression in these cells interferes with or upsets their normal differentiation programs and thus causes cell death. If this incompatibility exists, then it becomes plausible that cNSCL2 plays a role in safeguarding the development of amacrine and horizontal cells against inappropriate gene expression programs, such as those associated with glial or photoreceptor differentiation. It is possible that the development of a structure as complex as the retina may involve a selective mechanism by which cells that mistakenly express genes of another cell type would be eliminated. Another scenario is that the photoreceptor and glial atrophies were caused by microenvironment changes, such as the presence of high levels of metabolites toxic to these cells. Microenvironment changes could be caused by enhanced expression of cNSCL2 in horizontal cells and amacrine cells or misexpression of cNSCL2 in bipolar or ganglion cells. In preliminary experiments, E8 retinal cells were dissociated and cultured at low density for 3 to 4 days for scoring the number of photoreceptor cells, or more than 14 days for examining glial cell growth. Under these conditions, the number of visinin+ cells and the number of glial cells showed no differences between the experimental retina and the control retina. These would argue that the microenvironment played a role in causing the retinal degeneration in the experimental retinas. Keep in mind, however, that cellular properties may change under in vitro conditions. Müller glia are particularly known to change their morphologic and biochemical properties in vitro. Under our culture conditions, they readily re-entered the cell cycle. Therefore, the absence of glial and photoreceptor cell death in vitro does not necessarily show that their atrophiy in the retina is caused by the abnormal microenvironment in retinas misexpressing cNSCL2. Further studies using specific promoters to drive cNSCL2 misexpression in a cell type–specific manner may shed light on whether the loss of photoreceptors and glia is due to cNSCL2 misexpression in these cells or in other cells.

It is always of concern whether phenotypes observed in gain-of-function studies result from the presence of the exogenous protein itself or an alteration in the level of an endogenous protein. Because bHLH protein can form homo- or heterodimers, an exogenous bHLH protein could cause an imbalance of the endogenous bHLH proteins. Such an imbalance may produce nonspecific phenotypes. We have used RCAS to misexpress a number of bHLH genes including neuroD,14 cNSCL1,25,26 and neurogenin2 (Yan and Wang, unpublished results, 2000), in addition to cNSCL2. All these genes are homologous to the Drosophila proneural genes. Each gene misexpression manifests distinct phenotypes, not only at the gross level, but also at the microscopic level. Therefore, it is most likely that the phenotypes described in this report were specific to cNSCL2.

Our studies showed that cNSCL2 was cell type–specific in the retina and its misexpression caused severe photoreceptor degeneration and Müller glia atrophy. Thus, expression of cNSCL2 must be tightly regulated in the retina. If misexpression of a retinal gene causes retinal degeneration, it becomes important to regulate tightly and precisely the expression of genes that are artificially delivered into a tissue through, for example, gene therapies.

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Eye Institute Grant EY11640; unrestricted grants to the Department of Ophthalmology, University of Alabama at Birmingham from Research to Prevent Blindness and the Alabama Eye Institute.

Footnotes

Commercial relationships policy: N.

References

- 1.Kageyama R, Nakanishi S. Helix-loop-helix factors in growth and differentiation of the vertebrate nervous system. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1997;7:659–665. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(97)80014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guillemot F, Joyner AL. Dynamic expression of the murine Achaete-Scute homologue Mash-1 in the developing nervous system. Mech Dev. 1993;42:171–185. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(93)90006-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jasoni CL, Walker MB, Morris MD, Reh TA. A chicken Achaete-Scute homolog (CASH-1) is expressed in a temporally and spatially discrete manner in the developing nervous system. Development. 1994;120:769–783. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.4.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jasoni CL, Reh TA. Temporal and spatial pattern of MASH-1 expression in the developing rat retina demonstrates progenitor cell heterogeneity. J Comp Neurol. 1996;369:319–327. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960527)369:2<319::AID-CNE11>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gradwohl G, Fode C, Guillemot F. Restricted expression of a novel murine atonal-related bHLH protein in undifferentiated neural precursors. Dev Biol. 1996;180:227–241. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sommer L, Ma Q, Anderson DJ. Neurogenins, a novel family of atonal-related bHLH transcription factors, are putative mammalian neuronal determination genes that reveal progenitor cell heterogeneity in the developing CNS, and PNS. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1996;8:221–241. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1996.0060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanekar S, Perron M, Dorsky R, et al. Xath5 participates in a network of bHLH genes in the developing Xenopus retina. Neuron. 1997;19:981–994. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80391-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown NL, Kanekar S, Vetter ML, Tucker PK, Gemza DL, Glaser T. Math5 encodes a murine basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor expressed during early stages of retinal neurogenesis. Development. 1998;125:4821–4833. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.23.4821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perron M, Opdecamp K, Butler K, Harris WA, Bellefroid EJ. X-ngnr-1 and Xath3 promote ectopic expression of sensory neuron markers in the neurula ectoderm and have distinct inducing properties in the retina. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14996–15001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takebayashi K, Takahashi S, Yokota C, et al. Conversion of ectoderm into a neural fate by ATH-3, a vertebrate basic helix-loop-helix gene homologous to Drosophila proneural gene atonal. EMBO J. 1997;16:384–395. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.2.384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roztocil T, Matter-Sadzinski L, Alliod C, Ballivet M, Matter JM. NeuroM, a neural helix-loop-helix transcription factor, defines a new transition stage in neurogenesis. Development. 1997;124:3263–3272. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.17.3263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Acharya HR, Dooley CM, Thoreson WB, Ahmad I. cDNA cloning and expression analysis of neuroD mRNA in human retina. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;233:459–463. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perron M, Kanekar S, Vetter ML, Harris WA. The genetic sequence of retinal development in the ciliary margin of the Xenopus eye. Dev Biol. 1998;199:185–200. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.8939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yan R-T, Wang S-Z. neuroD induces photoreceptor cell overproduction in vivo and de novo generation in vitro. J Neurobiol. 1998;36:485–496. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morrow EM, Furukawa T, Lee JE, Cepko CL. NeuroD regulates multiple functions in the developing neural retina in rodent. Development. 1999;126:23–36. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guillemot F, Lo LC, Johnson JE, Auerbach A, Anderson DJ, Joyner AL. Mammalian achaete-scute homolog 1 is required for the early development of olfactory and autonomic neurons. Cell. 1993;75:463–476. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90381-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tomita K, Ishibashi M, Nakahara K, et al. Mammalian hairy and Enhancer of split homolog 1 regulates differentiation of retinal neurons and is essential for eye morphogenesis. Neuron. 1996;16:723–734. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yan R-T, Wang S-Z. Expression of an array of photoreceptor genes in chick embryonic RPE cell cultures under the induction of neuroD. Neurosci Lett. 2000;280:83–86. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)01003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yan R-T, Wang S-Z. Differential induction of gene expression by basic fibroblast growth factor and neuroD in cultured retinal pigment epithelial cells. Vis Neurosci. 2000;17:157–164. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800171172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Begley CG, Lipkowitz S, Gobel V, et al. Molecular characterization of NSCL, a gene encoding a helix-loop-helix protein expressed in the developing nervous system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:38–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.1.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown L, Espinosa R, Le Beau MM, Siciliano MJ, Baer R. HEN1 and HEN2: a subgroup of basic helix-loop-helix genes that are coexpressed in a human neuroblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:8492–8496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.18.8492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lipkowitz S, Gobel V, Varterasian ML, Nakahara K, Tchorz K, Kirsch IR. A comparative structural characterization of the human NSCL-1 and NSCL-2 genes. Two basic helix-loop-helix genes expressed in the developing nervous system. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:21065–21071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kannan K, Amariglio N, Rechavi G, et al. DNA microarrays identification of primary and secondary target genes regulated by p53. Oncogene. 2001;20:2225–2234. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Good DJ, Porter FD, Mahon KA, Parlow AF, Westphal H, Kirsch IR. Hypogonadism and obesity in mice with a targeted deletion of the Nhlh2 gene. Nat Genet. 1997;15:397–401. doi: 10.1038/ng0497-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li C-M, Yan R-T, Wang S-Z. Misexpression of a bHLH gene, cNSCL1, results in abnormal brain development. Dev Dyn. 1999;215:238–247. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199907)215:3<238::AID-AJA6>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li C-M, Yan R-T, Wang S-Z. Misexpression of cNSCL1 disrupts retinal development. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1999;14:17–27. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1999.0765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yan R-T, Wang S-Z. Identification and characterization of tenp, a gene transiently expressed before overt cell differentiation during neurogenesis. J Neurobiol. 1998;34:319–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hughes SH, Greenhouse JJ, Petropoulos CJ, Sutrave P. Adaptor plasmids simplify the insertion of foreign DNA into helper-independent retroviral vectors. J Virol. 1987;61:3004–3012. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.10.3004-3012.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bisgrove DA, Godbout R. Differential expression of AP-2alpha and AP-2beta in the developing chick retina: repression of R-FABP promoter activity by AP-2. Dev Dyn. 1999;214:195–206. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199903)214:3<195::AID-AJA3>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yan R-T, Wang S-Z. Embryonic abnormalities from misexpression of CNSCL1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;287:949–955. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu W, Wang JH, Xiang M. Specific expression of the LIM/homeodomain protein Lim-1 in horizontal cells during retinogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2000;217:320–325. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(200003)217:3<320::AID-DVDY10>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Belecky-Adams T, Tomarev S, Li H-S, et al. Pax-6, Prox1, and Chx10 homeobox gene expression correlates with phenotypic fate of retinal precursor cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997;38:1293–1303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xiang M, Zhou L, Macke JP, et al. The Brn-3 family of POU-domain factors: primary structure, binding specificity, and expression in subsets of retinal ganglion cells and somatosensory neurons. J Neurosci. 1995;15:4762–4785. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-07-04762.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cook B, Portera-Cailliau C, Adler R. Developmental neuronal death is not a universal phenomenon among cell types in the chick embryo retina. J Comp Neurol. 1998;396:12–19. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19980622)396:1<12::aid-cne2>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herman J-P, Victor JC, Sanes JR. Developmentally regulated and spatially restricted antigens of radial glial cells. Dev Dyn. 1993;197:307–318. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001970408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Linser P, Moscona AA. Induction of glutamine synthetase in embryonic neural retina: localization in Muller fibers and dependence on cell interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:6476–6480. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.12.6476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wahlin KJ, Campochiaro PA, Zack DJ, Adler R. Neurotrophic factors cause activation of intracellular signaling pathways in Muller cells and other cells of the inner retina, but not photoreceptors. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:927–936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]