Abstract

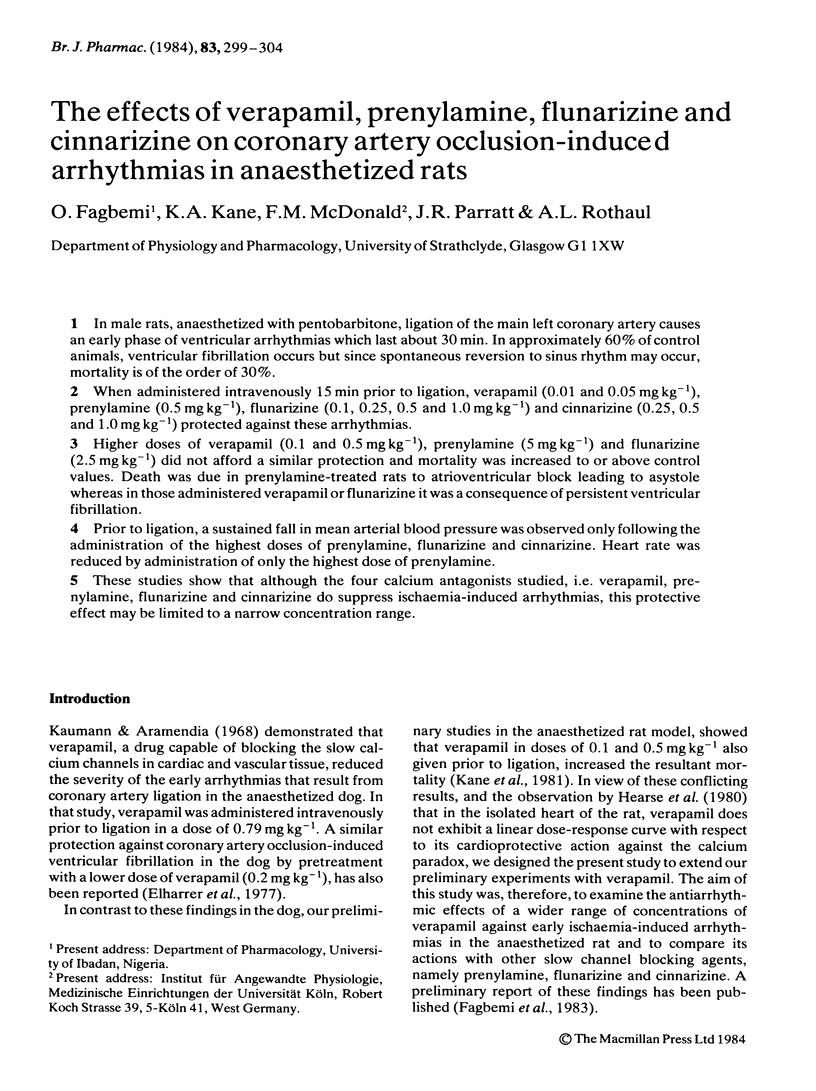

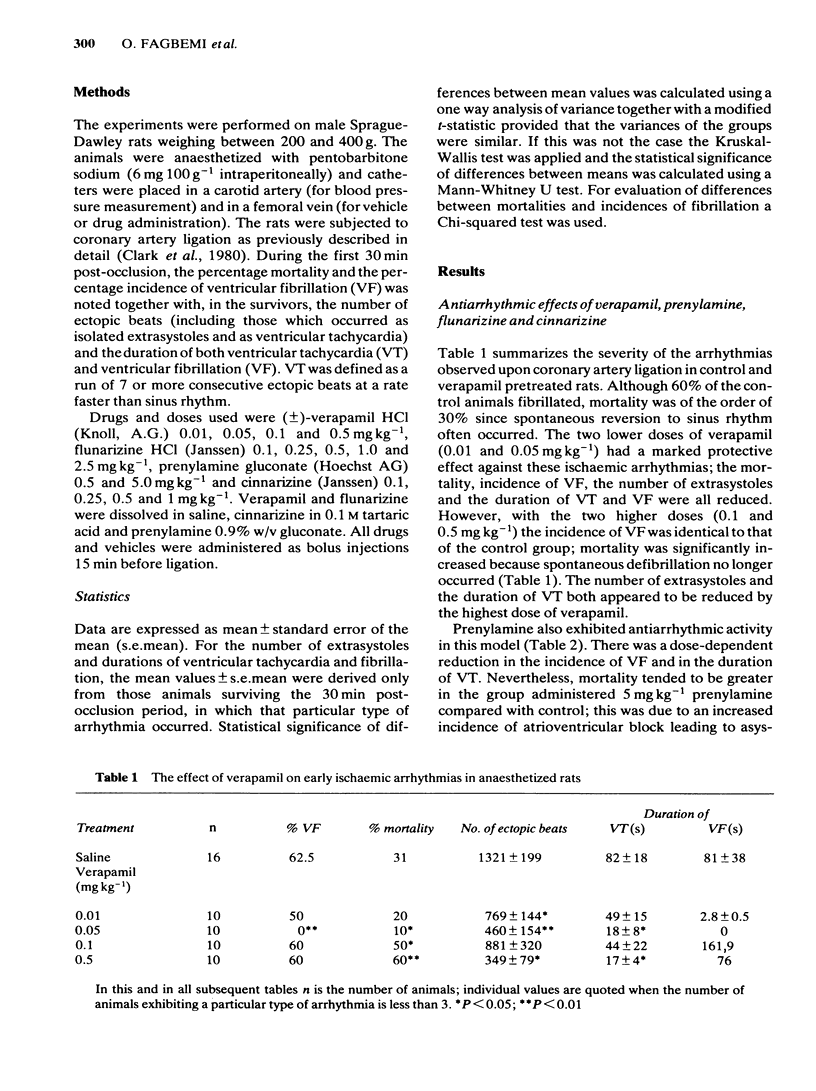

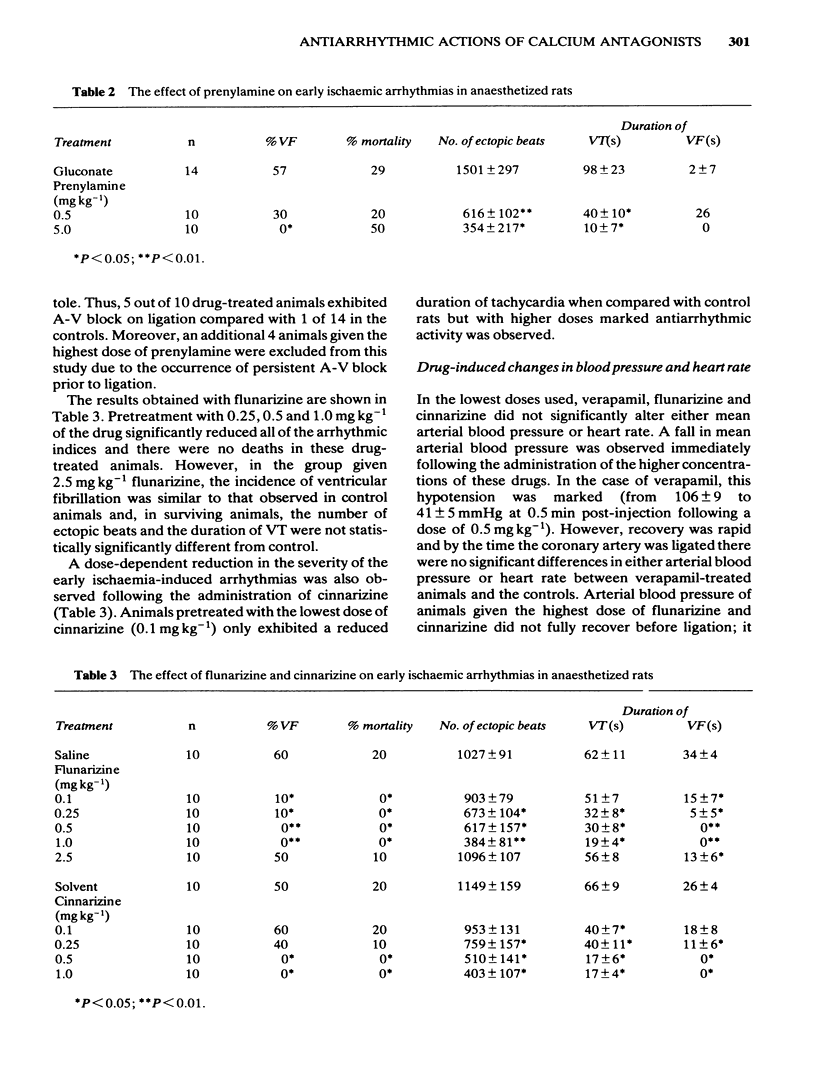

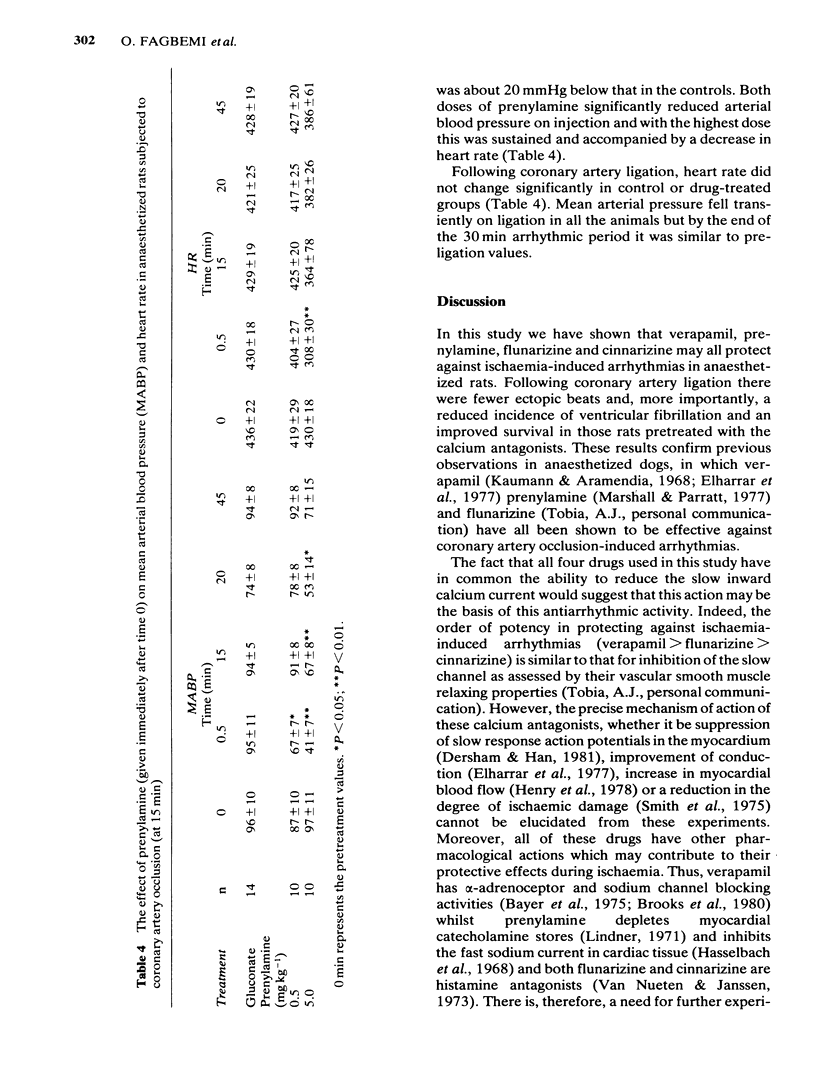

In male rats, anaesthetized with pentobarbitone, ligation of the main left coronary artery causes an early phase of ventricular arrhythmias which last about 30 min. In approximately 60% of control animals, ventricular fibrillation occurs but since spontaneous reversion to sinus rhythm may occur, mortality is of the order of 30%. When administered intravenously 15 min prior to ligation, verapamil (0.01 and 0.05 mg kg-1), prenylamine (0.5 mg kg-1), flunarizine (0.1, 0.25, 0.5 and 1.0 mg kg-1) and cinnarizine (0.25, 0.5 and 1.0 mg kg-1) protected against these arrhythmias. Higher doses of verapamil (0.1 and 0.5 mg kg-1), prenylamine (5 mg kg-1) and flunarizine (2.5 mg kg-1) did not afford a similar protection and mortality was increased to or above control values. Death was due in prenylamine-treated rats to atrioventricular block leading to asystole whereas in those administered verapamil or flunarizine it was a consequence of persistent ventricular fibrillation. Prior to ligation, a sustained fall in mean arterial blood pressure was observed only following the administration of the highest doses of prenylamine, flunarizine and cinnarizine. Heart rate was reduced by administration of only the highest dose of prenylamine. These studies show that although the four calcium antagonists studied, i.e. verapamil, prenylamine, flunarizine and cinnarizine do suppress ischaemia-induced arrhythmias, this protective effect may be limited to a narrow concentration range.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bayer R., Kalusche D., Kaufmann R., Mannhold R. Inotropic and electrophysiological actions of verapamil and D 600 in mammalian myocardium. III. Effects of the optical isomers on transmembrane action potentials. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1975;290(1):81–97. doi: 10.1007/BF00499991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks W. W., Verrier R. L., Lown B. Protective effect of verapamil on vulnerability to ventricular fibrillation during myocardial ischaemia and reperfusion. Cardiovasc Res. 1980 May;14(5):295–302. doi: 10.1093/cvr/14.5.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark C., Foreman M. I., Kane K. A., McDonald F. M., Parratt J. R. Coronary artery ligation in anesthetized rats as a method for the production of experimental dysrhythmias and for the determination of infarct size. J Pharmacol Methods. 1980 Jun;3(4):357–368. doi: 10.1016/0160-5402(80)90077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dersham G. H., Han J. Actions of verapamil on Purkinje fibers from normal and infarcted heart tissues. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1981 Feb;216(2):261–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elharrar V., Gaum W. E., Zipes D. P. Effect of drugs on conduction delay and incidence of ventricular arrhythmias induced by acute coronary occlusion in dogs. Am J Cardiol. 1977 Apr;39(4):544–549. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(77)80164-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearse D. J., Baker J. E., Humphrey S. M. Verapamil and the calcium paradox. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1980 Jul;12(7):733–739. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(80)90103-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaumann A. J., Aramendía P. Prevention of ventricular fibrillation induced by coronary ligation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1968 Dec;164(2):326–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning A. S., Shattock M. J., Dennis S. C., Hearse D. J. Long-term prenylamine therapy: effects on responses to myocardial ischaemia in the isolated rat heart. Eur J Pharmacol. 1982 Jan 8;77(1):33–38. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(82)90531-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall R. J., Parratt J. R. The haemodynamic and metabolic effects of MG 8926, a prospective antidysrhythmic and antianginal agent. Br J Pharmacol. 1977 Feb;59(2):311–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1977.tb07494.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayler W. G., Grau A., Slade A. A protective effect of verapamil on hypoxic heart muscle. Cardiovasc Res. 1976 Nov;10(6):650–662. doi: 10.1093/cvr/10.6.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selwyn A. P., Welman E., Fox K., Horlock P., Pratt T., Klein M. The effects of nifedipine on acute experimental myocardial ischemia and infarction in dogs. Circ Res. 1979 Jan;44(1):16–23. doi: 10.1161/01.res.44.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith H. J., Singh B. N., Nisbet H. D., Norris R. M. Effects of verapamil on infarct size following experimental coronary occlusion. Cardiovasc Res. 1975 Jul;9(4):569–578. doi: 10.1093/cvr/9.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Nueten J. M., Janssen P. A. Comparative study of the effects of flunarizine and cinnarizine on smooth muscles and cardiac tissues. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1973 Jul;204(1):37–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto F., Manning A. S., Braimbridge M. V., Hearse D. J. Cardioplegia and slow calcium-channel blockers. Studies with verapamil. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1983 Aug;86(2):252–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]