The electrophoretic mobility shift assay [EMSA]1 is one of the most sensitive methods for studying DNA-protein interactions. Chemiluminescence [CL]1 has been used as an alternative to radioisotopic detection of samples in the EMSA [1,2], as it has advantages such as safety and stability (no isotopic decay) of the sample. In this study, we examined the feasibility of the application of CL EMSA to studying heparin-living bacteria interactions. As an example, binding of biotinylated heparin to Escherichia coli was examined.

The pathogenesis of most infections is initiated by microbial adhesion to host tissue. This adhesion is, therefore, a promising target for the development of new antimicrobial therapeutics [3]. In the adhesion, heparin or heparin-related oligosaccharides are one of the extracellular matrix molecules of the host recognized by cell surface proteins of bacteria [4–8].

Due to the lack of appropriate techniques for the study of the interactions of heparin-living bacteria, most heparin-bacteria binding studies have been conducted with isolated bacterial proteins [9,10]. Although useful information can be obtained from such studies, one potential drawback is the exclusion of membrane phenomena such as ligand-induced receptor oligomerization that can affect the overall binding affinity [11].

Therefore, it is desirable to examine the adhesion process using bacteria in the intact state to include the membrane phenomena. With this purpose, scintillation counting of radioisotope radiation [12] and sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis [8] were used to assess the binding of heparin to living bacteria. More recently, atomic force microscopy was successfully used to investigate heparin-living bacteria interactions and producing quantitative data [13]. However, these methods are qualitative [8], require radioisotope labeling [12], an instrument, which may not be readily available in common laboratories [13].

EMSA has been widely employed to detect DNA-protein interactions since its first application [14]. In this study, CL EMSA is introduced to complement the existing methods to study heparin-bacteria interactions. CL has advantages such as safety and sample stability (no isotopic decay), while still exhibiting linearity between signal and sample quantity [15]. It has been applied to a quantitative binding study of RNA-protein [16] and heparin-protein interactions [17]. The underlying mechanism of CL generation is that biotin attached to heparin is recognized by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin. This enzyme catalyzes a chemical reaction to generate luminescence [15]. In this study, we examined the feasibility of CL EMSA to quantitatively study of heparin-living bacteria interactions using E. coli as a model system.

An overnight culture of a commercial E. coli strain, BL21 (DE3) carrying pLysS and pTYB1 (New England Biolab, Beverly, MA) was centrifuged and washed two times with PBS1 and resuspended in the buffer. Aliquots of the E. coli containing buffer were used for the measurement of OD600 (optical density at 600 nm) of the cells and in the heparin binding assay. Luria-Bertani broth and plates contained 50 μg/ml ampicillin and 34 μg/ml chloramphenicol. From the number of E. coli colonies on the plate after spreading the cells with a defined volume and the OD600, we obtained the relationship between OD600 and the E. coli concentration in PBS. Colony numbers (y) on the plates were fit to Eq. (1) by linear regression using Mathematica (Wolfram Research, Champaign, IL).

| (1) |

where x is the volume (μl) multiplied by 10−6 × OD600 of the cell solution spread on a plate. The constant a was obtained as 0.46 ± 0.02 and R2 for the fitting was 0.992. This suggests that one OD600 of the cells corresponds to 0.76 pM.

Binding of biotinylated heparin (Sigma, St Louis, MO) to E. coli was achieved by incubating 5 nM biotinylated heparin in PBS and a variable quantity of the bacteria in a 10 μl reaction volume for 1 h at room temperature. The total quantity of biotinylated heparin in the reaction mixture was 50 fmol, which is within the linear signal range [17]. Then, the binding mixtures were combined with 6x gel-loading buffer (0.25% bromophenol blue and 30% glycerol) and electrophoresed on an 8% polyacrylamide gel in 1x trisborate/EDTA buffer at 100 V for 30 min. Heparin in the gel was transferred to Biodyne nylon membranes (Pierce, Rockford, IL) by electroblotting at 100 V for 1 h using a Mini Trans-Blot Cell (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and detected using a LightShift Chemiluminescent EMSA kit (Pierce) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Omission of the UV crosslinking step because of the absence of crosslinkable double bonds in heparin, unlike nucleic acids, did not cause a problem in the detection, indicating the electroblotting was sufficient for the attachment of heparin to a nylon membrane. The CL IDV1 of biotinylated heparin was quantitatively measured with a cooled CCD1 camera (Fluor Chem 8800 Imaging system, Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA) [18] with autobackground subtraction.

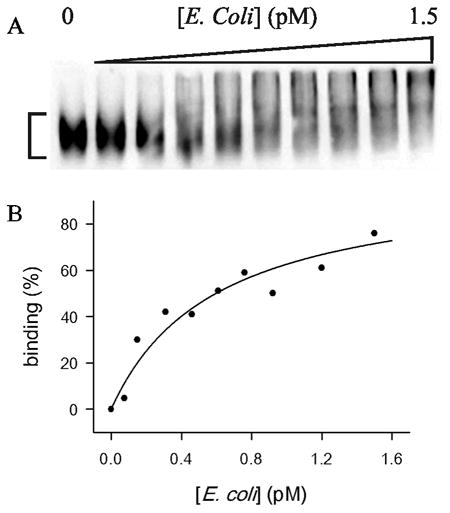

Obviously, the size of E. coli is huge so that any shifted bands were not detected (Fig. 1A). Degree of binding (B) of heparin to E. coli was assessed by Eq. (2):

Fig. 1.

CL EMSA of biotinylated heparin and E. coli interaction. (A) E. coli concentrations were increased up to 1.5 pM. The region for the measurement of the CL IDV of unbound biotinylated heparin is marked. The smearing between the well and unbound heparin in the gel indicates dissociation of bound heparin during electrophoresis. (B) Degree of binding (%) obtained from Eq. (2) was plotted against E. coli concentration in pM (closed circle). The data were fit to Eq. (7) (solid line).

| (2) |

where IDVC, and IDV0 are the IDV of unbound heparin at the concentration C of the cell or without the cell, respectively.

Binding of heparin (H) to the protein (P) on the bacterial cell surface was modeled in the following way.

| (3) |

The relationship between degree of heparin-protein binding (BHP) and protein concentration [P] corresponding Eq. (3) is:

| (4) |

where K is the dissociation constant. Here, the total protein concentration was used for [P] as the heparin concentration used in the titration was significantly less than the dissociation constants of most known heparin-protein bindings [9]. This is another advantage of CL EMSA, as it requires a very small quantity of biotinylated material for detection because of its high sensitivity [16,17]. It is desirable to express Eq. (4) using the experimental variable, total E. coli concentration [E] so that the experimental measurement (Eq. (2)) can be applied directly. If the number of the heparin-binding proteins on the cell surface of one bacterium is n, then Eq. (4) can be converted to Eq. (5) by substituting n × [E] for [P]:

| (5) |

Eq. (5) can be used to derive a degree of binding (BHE) of a hypothetical one-to-one heparin-bacteria association (Eq. (6)) with apparent dissociation constant, K/n:

| (6) |

The BHE of Eq. (6) is then,

| (7) |

Of course, a single bacterium binds many heparin molecules. However, if there is no significant difference of affinity among the heparin-binding sites, then Eqs. (6) and (7) are appropriate for the description of binding performed in this study.

Eq. (7) was applied in the fitting of values obtained from Eq. (2) by nonlinear regression using Mathematica. K/n and R2 values obtained from the fitting were 0.60 ± 0.06 pM and 0.927, respectively (Fig. 1B). Such high affinity is obviously attributed to the presence of multiple copies of the heparin-binding sites on the cell surface. The constant K/n obtained from the fitting is not a true thermodynamic equilibrium constant because of the multiplicity and potential heterogeneity of the heparin-binding sites on the cell surface. However, the value can be used for the comparison of relative heparin-binding affinity between different bacterial species if the titration is performed with the same concentration of heparin.

In summary, the applicability of CL EMSA for the quantitative assessment of heparin-living bacteria binding was examined with E. coli and biotinylated heparin. This method can be readily applied to heparin-bacteria binding study to assess relative heparin-binding affinity of bacteria as it has several advantages such as safety and stability of the sample, high sensitivity and the linearity of signal, and relative ease of performance. In addition, the binding conditions such as buffer composition and temperature can be varied. Most importantly, the binding can be examined with living bacteria. As in the study of DNA-protein interactions, CL EMSA is expected to be widely used for heparin-bacteria interaction studies complementing existing methods specially for the study of heparin binding of the commensal microorganisms as their huge diversity (500–1000 species in human gut) [19] requires a fast method.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the U.S. Edgewood Chemical Biological Center (W911 SR-04-C-0065), NIH (AI27744 and U01 AI054827), NHLBI (N01HV28184), and the Welch Foundation (H1296). We thank David E. Volk for critical reading of the manuscript and valuable suggestions.

Abbreviations used

- EMSA

electrophoretic mobility shift assay

- CL

chemiluminescence

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- IDV

integrated density value

- CCD

charge-coupled device

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Berger R, Duncan MR, Berman B. Nonradioactive gel mobility shift assay using chemiluminescent detection. BioTechniques. 1993;15:650–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ikeda S, Oda T. Nonisotopic gel-mobility shift assay using chemiluminescent detection system. BioTechniques. 1993;14:878–880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patti JM, Allen BL, McGavin MJ, Hook M. MSCRAMM-mediated adherence of microorganisms to host tissues. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1994;48:585–617. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.48.100194.003101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rostand KS, Esko JD. Microbial adherence to and invasion through proteoglycans. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.1.1-8.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aoki K, Matsumoto S, Hirayama Y, Wada T, Ozeki Y, Niki M, Domenech P, Umemori K, Yamamoto S, Mineda A, Matsumoto M, Kobayashi K. Extracellular mycobacterial DNA-binding protein 1 participates in mycobacterium-lung epithelial cell interaction through hyaluronic acid. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:39798–39806. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402677200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ascencio F, Fransson LA, Wadstrom T. Affinity of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori for the N-sulphated glycosaminoglycan heparan sulphate. J Med Microbiol. 1993;38:240–244. doi: 10.1099/00222615-38-4-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baron MJ, Bolduc GR, Goldberg MB, Auperin TC, Madoff LC. Alpha C protein of group B Streptococcus binds host cell surface glycosaminoglycan and enters cells by an actin-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:24714–24723. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402164200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fleckenstein JM, Holland JT, Hasty DL. Interaction of an outer membrane protein of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli with cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Infect Immun. 2002;70:1530–1537. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.3.1530-1537.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Capila I, Linhardt RJ. Heparin-protein interactions. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2002;41:391–412. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020201)41:3<390::aid-anie390>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muñoz EM, Linhardt RJ. Heparin-binding domains in vascular biology. Arteriorscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:1549–1557. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000137189.22999.3f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bormann BJ, Engelman DM. Intramembrane helix-helix association in oligomerization and transmembrane signaling. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1992;21:223–242. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.21.060192.001255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen JC, Zhang JP, Stephens RS. Structural requirements of heparin binding to Chlamydia trachomatis. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:11134–11140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dupres V, Menozzi FD, Locht C, Clare BH, Abbott NL, Cuenot S, Bompard C, Raze D, Dufrene YF. Nanoscale mapping and functional analysis of individual adhesions on living bacteria. Nat Methods. 2005;2:515–520. doi: 10.1038/nmeth769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garner MM, Revzin A. A gel electrophoresis method for quantifying the binding of proteins to specific DNA regions: application to components of the Escherichia coli lactose operon regulatory system. Nucleic Acids Res. 1981;9:3047–3060. doi: 10.1093/nar/9.13.3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang J, Lee MS, Gorenstein DG. Quantitative analysis of chemiluminescence signals using a cooled charge-coupled device camera. Anal Biochem. 2005;345:66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kang J, Lee MS, Watowich SJ, Gorenstein DG. Chemiluminescence-based electrophoretic mobility shift assay of RNA-protein interactions: Application to binding of viral capsid proteins to RNA. J Virol Methods. 2006;131:155–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang J, Lee MS, Gorenstein DG. Chemiluminescence-based electrophoretic mobility shift assay of heparin-protein interactions. Anal Biochem. 2006;349:156–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kang J. Application of a cooled charge-coupled device (CCD) camera for the detection of chemiluminescence signal. Biologicals. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2006.09.002. (In press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu J, Gordon JI. Honor thy symbionts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:10452–10459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1734063100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]