Abstract

Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF), a proinflammatory cytokine central to the response to endotoxemia, is a putative biomarker in acute lung injury (ALI). To explore MIF as a molecular target and candidate gene in ALI, we examined MIF gene and protein expression in murine and canine models of ALI (high tidal volume mechanical ventilation, endotoxin exposure) and in patients with either sepsis or sepsis-induced ALI. MIF gene expression and protein levels were significantly increased in each ALI model, with serum MIF levels significantly higher in patients with either sepsis or ALI compared to healthy controls (African- and European- descent). We next studied the association of 8 MIF gene polymorphisms (SNPs) (within a 9.7 kb interval on chromosome 22q11.23) with the development of sepsis and ALI in European- and African- descent populations. Genotyping in 506 DNA samples (sepsis patients, sepsis-associated ALI patients, and healthy controls) revealed haplotypes located in the 3′ end of the MIF gene, but not individual SNPs, associated with sepsis and ALI in both populations. These data, generated via functional genomic and genetic approaches, suggest that MIF is a relevant molecular target in ALI.

Keywords: mechanical ventilation, MIF, gene expression profiling, polymorphism

Introduction

Severe acute lung injury (ALI), a life-threatening disorder produced by diverse stimuli (sepsis, trauma, gastric acid aspiration) with unacceptable morbidity and mortality,1 is characterized by complex spatially-defined multicellular activation and inflammatory cell influx. The marked physiologic derangements which invariably ensue necessitate the use of supportive mechanical ventilation for respiratory failure. Unfortunately, the mechanical stress produced by excessive mechanical ventilation, is now recognized as an additional key contributor to lung inflammation and a vital determinant of lung injury.2,3 Although complex lung diseases are likely to be influenced by genetic factors,4 few genes have been rigorously implicated in ALI susceptibility or severity.5 Clearly, the identification of genetic determinants and novel therapeutic targets for ALI is essential to reduce the incidence and mortality associated with this devastating condition.

Increasing evidence supports the notion that the cytokine known as macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) participates in the pathogenesis of acute and chronic inflammatory and autoimmune disorders, such as sepsis, ALI/ARDS, asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease.6 Originally described as a product of activated T cells that inhibits macrophage migration, MIF represents a putative biomarker and potential molecular target in ALI as anti-MIF antibodies were protective in a murine model of sepsis,7 and MIF is detectable in the alveolar airspaces of patients with sepsis-induced ARDS.8 MIF regulates both the set-point and the direction of the inflammatory response by counter-regulating the anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects of glucocorticoids.9,10 For example, MIF directly increases IL-8 and TNFα production and overrides glucocorticoid-mediated inhibition of cytokine secretion.11 Both TLR4 mRNA and protein expression were reduced in MIF-deficient cells resulting in hypo-responsiveness to endotoxin and gram-negative bacteria.12 In addition, we recently showed the direct interaction of MIF with the nonmuscle Ca2+/calmodulin (CaM)-dependent myosin light chain kinase isoform,13 a multifunctional protein centrally involved in multiple aspects of the inflammatory response14-17 and whose genetic variants influence the susceptibility to sepsis and ALI18 as well as severe asthma in African Americans.19

To examine the role of MIF in ALI, we analyzed gene and protein expression patterns in lung tissue from murine and canine models of sepsis and ventilator-associated ALI (VALI), and in BAL cells and serum from ALI patients. These studies showed increased MIF expression (locally and systemically), validating MIF as a potential biomarker in ALI. Case-control association studies demonstrated population-specific MIF gene haplotypes associated with protection and susceptibility to sepsis and ALI in both European and African American populations. These data, utilizing complementary functional genomic and genetic approaches, indicate that MIF is a relevant molecular target in ALI whose polymorphisms potentially contribute to the racial disparity observed in ALI morbidity and mortality.

Methods

Animal models

All experiments were institutionally approved as described previously.20,21 Briefly, male C57BL6 mice (25-30g) were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (60 mg/kg) administered intraperitoneally. Control mice were allowed to breathe spontaneously. A water-jacketed (37°C) chamber with water and perfusion pumps (Hugo Sachs Elektronik, March-Hugstetten, Germany) was used for surgery, perfusion, and murine lung ventilation (Harvard Apparatus, Boston, MA). After tracheotomy and tracheal cannulation, mice were exposed to either: 1) intratracheal instillation of lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 50 μg dissolved in 50 μl of saline); 2) high tidal volume ventilation (HVT, room air, 35 ml/kg, 60 breaths/min; 2 hours); or 3) intratracheal LPS with high tidal volume ventilation (LPS+HVT). In selected experiments, BAL samples were obtained from mice exposed to low tidal volume ventilation (LVT, 7 ml/kg, 120 breaths/min; 2 hours) for assessment of MIF protein levels. The canine ALI model as described previously21-23 employed unilateral saline lavage-induced lung injury, with independent high tidal volume left lung ventilation (15 ml/kg, 5 hrs) and with uninjured right lung used as control.21

Human bronchoalveolar lavage samples

Utilizing IRB-approved protocols, human BAL samples were obtained from ALI patients (n = 3) and healthy controls (n = 3) as described previously.21 Briefly, after informed consent, human BAL samples were obtained from patients with ALI and non-smoking subjects by instilling 100 ml of normal saline via a bronchoscopy into the right middle lobe. BAL cells were pelleted and frozen at −80°C in Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) until use. BAL cell RNAs were used for microarray analyses. Three normal control BALs were sex and age matched.

Gene expression profiling and real-time PCR validation

The Affymetrix GeneChip system and platform was used to generate the gene expression profiles and basic statistical analysis of the GeneChip microarray data including the global normalization, detection and change calls with the One-Sided Wilcoxon's Signed Rank tests, and data filtering was carried out using the Affymetrix® Microarray Suite software (MAS 5.0) as we described previously.21 We further validated MIF mRNA expression by real-time PCR with the first strand cDNA synthesized from 1 ug of DNase digested total RNA of each sample using random hexamers and Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) at a final concentration of 0.25U/μl for 1 hour at 37°C. One-tenth of the cDNA product was employed for real time PCR, by triplicate, using ABI PRISM 7700 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems) following manufacturer's recommendations. A custom TaqMan® Gene Expression Assay was designed for the mouse MIF gene sequence (GenBank Accession Number NM_010798.1) consisting on: forward primer, 5′-CAGAACCGCAACTACAGTAAGCT-3′; reverse primer, 5′-GCAGCGTTCATGTCGTAATAGTTGA-3′; and FAM™ dye - MGB labeled probe, 5′-CCGATCGCCTGCACATC-3′. TaqMan® Rodent GAPDH Endogenous Control (Cat. #4308313) was used as a housekeeping gene for normalization. Ready-to-use TaqMan® Gene Expression Assays (Hs00236988_g1 for MIF assay and Hs99999903_m1 for β-actin as a normalization gene) were used for human BAL cDNAs. The human MIF assay (Hs00236988_g1) was used for canine cDNA quantification (The TaqMan® Ribosomal RNA was used for normalization (Cat. #4308329)). The TaqMan® Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) was used for all the assays. Relative quantification of gene expression using the comparative ΔΔCT method was performed after demonstrating approximately equal efficiency between MIF and the gene for normalization.

Statistical significant changes of signal intensity were tested using either the two-tailed student's t-test or ANOVA. For all tests, P < 0.05 was taken as significant.

Quantification of MIF protein

MIF protein levels were assessed in BAL fluid derived from ALI murine models by Western Blot probing with monoclonal MIF- specific antisera (R & D system, Minneapolis, MN). Since there is no known standardized biomarker present in the BAL fluid after lung injury, equal loading of 10 μg total protein was ensured using the BCA Protein Assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). The size of MIF on gel is 12 kDa. MIF expression (fold change) was quantified by densitometry scanning. We have repeated these studies (Western blots, n=3-6) and analyzed the means to assure the validity of our observation. A least significant difference multiple-range test and a randomized one way analysis of variance were utilized.

Complementary ELISA assays were used to quantify immunoreactive MIF in serum (Quantikine Human MIF Immunoassay kit, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Samples were analyzed in triplicate with an initial 10-fold dilution. Color development was allowed to proceed for 30 min, and optical densities (OD) of 450 nm were detected with wavelength correction at OD 540 nm. The equation from the line of best fit for the standards was used to determine serum MIF concentration. Samples generating values higher than the highest standard were reanalyzed by serial dilution until the OD 450 nm fell within the linear range of the standard curve. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS (SPSS, Chicago, IL). To compare values between and among groups, Mann-Whitney U-test, Kruskal-Wallis and paired t-tests were used as appropriate. Values were considered significantly different for P < 0.05.

Lung immunochemistry

Paraffin-embedded sections (5 μm) of mouse lung from control, HVT, LPS and HVT-LPS models were prepared for immunohistochemistry. Paraffin was removed by heating at 60°C and re-hydrated in xylene, graded alcohols, and water. Antigen retrieval involved incubation with citrate buffer and steamer for 20 min. Endogenous peroxide activity was quenched using 3% H2O2 (Sigma) in distilled water. Non-specific binding was eliminated by incubating sections in working solution of blocking serum for 30 min (Vectastain Universal Quick Kit, Vector, Burlingame, CA). Primary antibody dilution (mouse anti- MIF monoclonal antibody (IgG1 subclass), at 0.13 μg/ml concentration) was made in PBS buffer containing 1.5% blocking serum then at room temperature for 1 h. The slides were then incubated in a biotinylated secondary antibody solution for 30 min, followed by a solution of streptavidin/peroxidase complex for 5 min (Quick Kit, Vector), and developed in 3,3′-diaminobenzidine in chromogen solution for 3-4 min (DAB Chromogen, Dako). The images were captured at 40x lens magnification using a Nikon E800 microscope and a Nikon CCD 8-bit color camera, with similar levels of brightness, and white background correction. To ensure specificity of the staining, the following labeling controls were performed: (i) replacement of primary antibodies with pre-immune rabbit immunoglobulin; and (ii) background staining was carried out without the primary antibodies or the peroxidase-labeled polymer.

Case-control population

This case-control association study was approved by the JHU Institutional Review Board as described18 involving 506 DNA samples consisting of 288 European American subjects (113 patients with severe sepsis, 90 sepsis-associated ALI, and 85 healthy controls), and 218 African American subjects (69 with severe sepsis, 61 with sepsis-associated ALI, and 88 healthy controls). Definitions of sepsis and ALI were in accordance with the American College of Chest Physicians24 and Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus statements.25 Inclusion and exclusion criteria were described previously.18 APACHE II scores were recorded to ensure comparability of the severity of illness between ALI and sepsis groups.25 Healthy control subjects were defined as individuals without any recent acute illness or any chronic illness requiring a physician's care.

SNP selection and genotyping

Eight SNPs, distributed across 9.7 kb of the MIF gene, were selected for genotyping based on: a) availability and validated status in ABI TaqMan® SNP Genotyping Assays list (rs875643, rs9282783, rs2070767, rs1007889, rs1007888, and rs5751761), b) validation by previous re-sequencing studies27 (ie. rs2070766 at +656 in intron 2), and c) previous known disease associations (rs755622 at −173 in the promoter).27-30 Genotyping was performed using the 5′ nuclease TaqMan® allelic discrimination assay on the 7900HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) as previously described.18,21 Randomly selected samples (∼10%) were repeated as routine quality control procedure to assess genotyping reproducibility.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed utilizing either SigmaStat (ver 3.1, SPSS) or Stata (v8.0). In the association study, departures from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium at each locus were tested by means of the chi-squared test separately for cases and controls. Crude odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for association of individual SNPs were assessed by means of SNPstats31 and the significance obtained by chi-square tests. This software was also used to choose between co-dominant, recessive and dominant inheritance models on the basis of Akaike Information Criteria and to obtain individual SNP adjusted odds ratios using logistic regression models including age and gender as covariates. For that purpose, age was recorded as a categorical variable, which fit best into a regression model, of three categories including ≤40, 41-59 and ≥60 years. Haploview v3.2 was used for linkage disequilibrium (LD) exploration and haplotype block definition.32 Blocks were extended if ≥95% of comparisons included D' values with evidence of strong LD (minima 95% D' confidence interval = 0.70-0.98), and ignoring SNPs with MAF<5%.33 An initial haplotype scan was performed by means of SNPem using sliding windows of 2-4 SNPs and the p-values for haplotypes frequency differences tested by 10,000 permutations, as described previously.34 Both SNPstats and SimHap35 were used to calculate the odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals the associated haplotypes, taking into account the uncertainty in haplotype reconstruction, by means of logistic regression models including age and gender.

Results

MIF gene expression in animal and human ALI

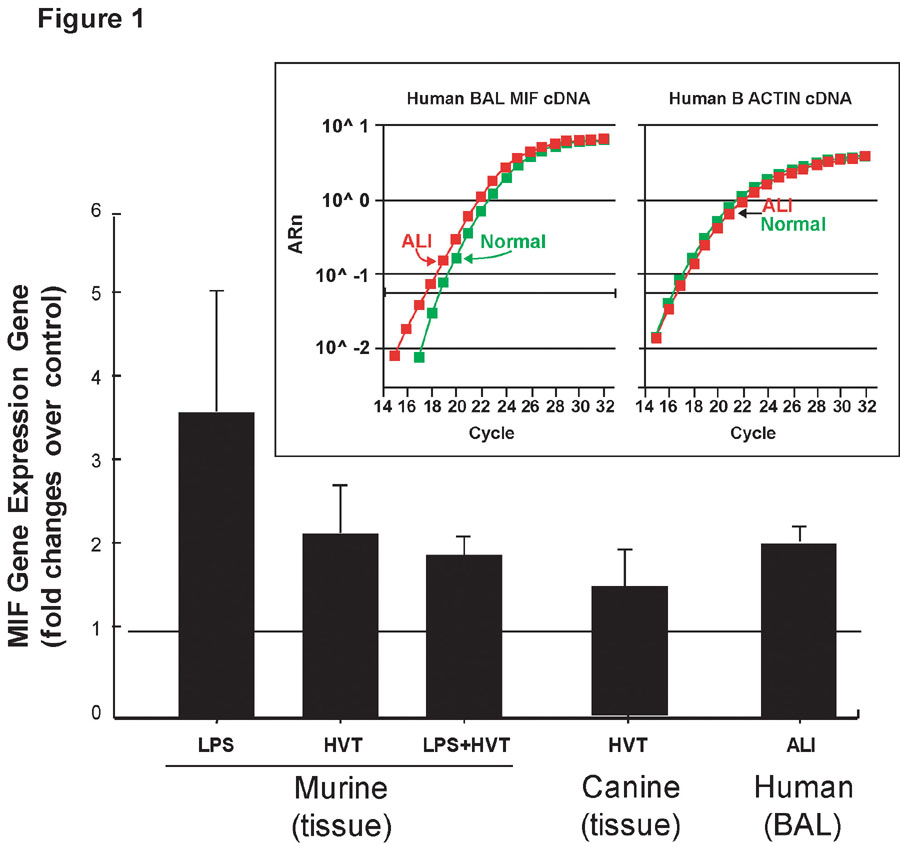

To evaluate MIF gene expression, we isolated RNA from lung tissues derived from animal ALI models (canine, murine) and from human BAL cells. Both murine and canine ALI models of inflammatory lung injury demonstrated clear biochemical and physiologic evidence of alveolar and endothelial cell barrier dysfunction with increased levels of BAL protein, increased Evans blue dye leakage into lung tissue and histologic evidence of lung inflammation.20,22 MIF gene expression detected by Affymetrix microarray increased significantly (P < 0.05) with increased fold changes ranging from 2.30 ± 0.64 to 2.89 ± 1.10 in murine and canine ALI models and increases to 1.69 ± 0.01 in BAL from ALI patients (Table I). Significantly higher lung MIF gene expression was confirmed by real time PCR (Figure 1) in the murine LPS model of ALI (3.63 ± 1.46 fold increase, n = 3, P < 0.04), the high tidal volume model (2.18 ± 0.67 fold increase, n = 5, P < 0.04), the LPS plus HVT model (1.92 ± 0.22 fold increase, n = 3, P < 0.01), the canine ALI model (1.55 ± 0.21 fold increase, n = 3, P < 0.01), and BAL from ALI patients relative to age- and sex-matched controls (2.21 ± 0.12 fold increase, n = 3, P < 0.01). The Figure 1 insert depicts a representative real time PCR experiment validating MIF gene up-regulation.

Table I.

MIF expression in murine and canine lung tissue in ALI models and human ALI BAL detected by Affymetrix microarrays.

| ALI Models (N) | Fold increasea |

|---|---|

| Murine lung tissue with LPSb (3) | 2.89 ± 1.10* |

| Murine lung tissue with HVTc (4) | 2.73 ± 0.94* |

| Murine lung tissue with LPS and HVTc (3) | 2.42 ± 0.55* |

| Canine lung tissued with HVTc (4) | 2.30 ± 0.64* |

| Human BAL (3) | 1.69 ± 0.01* |

Average fold increase (± SD) of MIF expression lung tissue samples compared to controls.

LPS: intratracheal instillation of 50 μg LPS dissolved in 50 μl of saline.

HVT: high tidal volume (35 ml/kg) ventilation for 2 h.

Left lung was ventilated independently with high tidal volume (15 ml/kg) for 5 h (the right lung is used as uninjured control).

Unpaired t-test, P < 0.05.

Figure 1. Real-time PCR validation of MIF mRNA levels in lung tissues of murine and canine ALI models and in human BAL.

Relative levels (mean fold change ± SD) of MIF mRNA expression were detected by real-time PCR. MIF gene expression was significantly increased in both murine and canine ALI models as well as in BAL from ALI patients. Unpaired t-test was used, P < 0.05 for all comparisons to controls. The insert depicts a representative real-time PCR amplification plot comparing MIF (left) and β-actin (right) mRNA expression in BAL samples from ALI patients and controls.

MIF localization in murine ALI

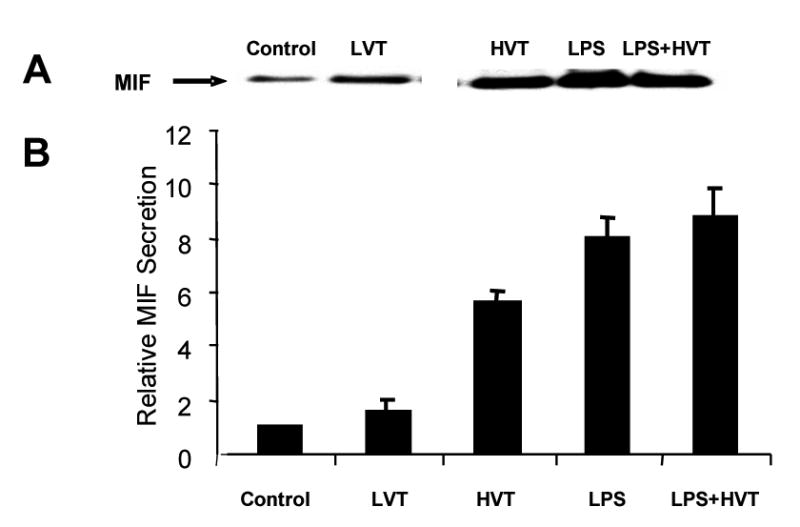

We next validated that up-regulation of MIF gene expression was linked to increases in MIF protein levels and measured MIF protein in BAL fluids of the experimental murine models utilized (Figure 2). We noted a ∼5-fold increase in BAL MIF protein in the murine high tidal volume (HTV) ALI model, and an ∼8-fold increase in the murine LPS model of ALI (P < 0.05 for all comparisons to control mice). Consistent with the microarray data, MIF protein levels were not additive in mice challenged with both LPS and high tidal volume ventilation. Immunohistochemical studies confirmed increased MIF in mice exposed to either high tidal volume (35 ml/kg) ventilation or to LPS (primarily within alveolar endothelium and macrophages) but without additive or synergistic MIF staining in dually challenged animals (data not shown).

Figure 2. Induction of MIF secretion after LPS and HVT treatment in murine ALI models.

Panel A. Depicted is a representative immunoreactive MIF band (size of MIF on gel is 12KD) reflecting MIF protein level in murine BAL fluid by equal protein loading (10 ug of total protein). Panel B. The bar graph demonstrates the average fold changes in MIF protein levels from four different experiments. There was significant increase in BAL MIF protein in both the high tidal volume ALI model (HVT, 35 ml/kg, ∼ 5-fold) and the LPS model of ALI (LPS, ∼ 8-fold). No additive effect was observed in MIF protein levels in mice challenged with both LPS and high tidal volume ventilation (LPS+HVT). MIF protein in mice exposed to low tidal volume ventilation (LVT, 7 ml/kg) is used in addition to the controls without ventilation. A least significant difference multiple-range test and a randomized one way analysis of variance were utilized. All comparisons to control mice are significant (P < 0.05).

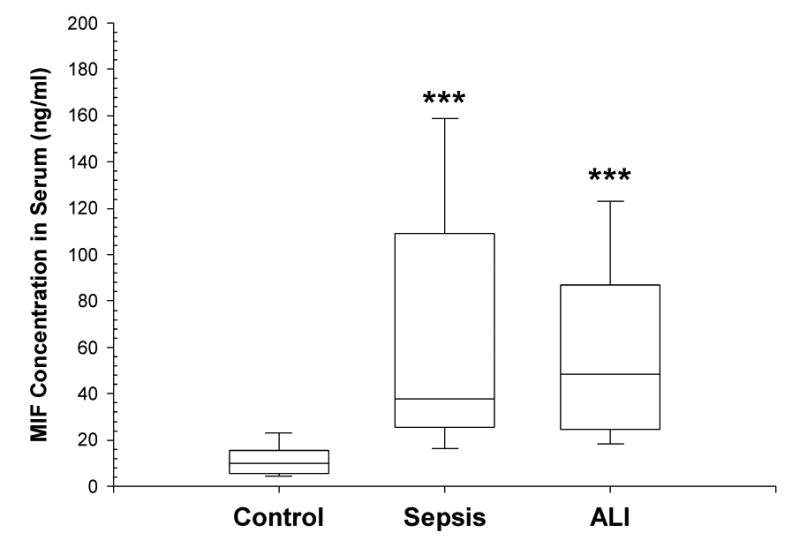

MIF serum levels

MIF serum levels (generally obtained within a 72 hour time frame) were studied in 142 samples from controls and patients with sepsis or ALI (53 controls, 36 sepsis patients and 53 sepsis-induced ALI patients) (Table II). Circulating MIF levels were significantly increased (P < 0.001) in both the sepsis and ALI groups (37.6 and 48.5 ng/ml, respectively), compared to the controls (9.9 ng/ml) (Figure 3) in a gender-independent way. However, MIF levels in sepsis alone and ALI patients were not significantly different from each other (Mann-Whitney rank sum test, P = 0.3). A significant correlation of MIF levels was not identified with either the APACHE II score or mortality. Although not statistically significant, there was a trend for increased MIF levels in ALI non-survivors (73.48 ± 39.82 ng/ml, n=19) compared with survivors (53.36 ± 27.22 ng/ml, n=34), findings consistent with the notion that serum MIF level may be used as a predictive variable for ALI outcome.11 Additional studies with careful attention to the timing of the serum sample acquisition in larger ALI and sepsis cohorts is necessary to more fully evaluate this trend.

Table II.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the studied population.

| ALI | Sepsis | Healthy Controls | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EAa | AAb | EAa | AAb | EAa | AAb | |

| N | 90 | 61 | 113 | 69 | 85 | 88 |

| Gender (M/F) | 53/37 | 35/22f | 63/50 | 37/23f | 41/44 | 23/64f |

| Agec | 53.9 ± 16.9 | 48.5 ± 16.3 | 60.8 ± 18.4 | 57.9 ± 16.9 | 32.7 ± 10.5 | 37.1 ± 10.8 |

| APACHE IIc | 20.4 ± 6.6 | 24.5 ± 7.8 | 20.5 ± 6.3 | 21.1 ± 6.2 | N.A. | N.A. |

| Mortality (%) | 40 (30/75)f | 47.2 (25/53)f | 28 (25/90)f | 33 (15/46)f | N.A. | N.A. |

EA: European descent Americans.

AA: African Americans.

Expressed as mean ± SD.

Numbers do not match to the number of initial samples due to missing data.

N/A: not applicable.

Figure 3. Boxplots of serum MIF protein levels.

Serum MIF levels were measured utilizing a MIF ELISA kit as noted in the Methods section. The bottom, median and top lines of the box mark the 25th, 50th and 75th percentiles, respectively. The vertical line shows the range of values comprised between the 5th and 95th percentiles. Median (range) concentrations of MIF were 9.95 ng/ml (3.37 – 35.18) in controls (n = 53), 37.59 ng/ml (10.30 – 198.98) in patients with sepsis (n = 36) and 48.5 ng/ml (9.51 – 184.55) in patients with sepsis- associated ALI (n = 53).

Case-control association study

The demonstration of increased MIF gene and protein expression in experimental models of ALI are remarkably consistent with published studies in humans8,11,36 and further strengthen MIF as a viable candidate gene whose variants may potentially explain the observed heterogeneity in ALI susceptibility and severity. To address this issue, we next performed a case-control association study of patients with severe sepsis, sepsis-associated ALI and healthy controls with demographic and disease severity characteristics depicted in Table II. Age, gender and APACHE II scores were not significantly different between the European and African American populations within the sepsis and ALI cohorts, although age and gender of the control subjects in both populations were significantly different compared to the patient groups (P < 0.01). Mortality rates were significantly increased in the ALI group (∼42%) compared to sepsis group (∼29%) in both European and African descent participants (P = 0.029). Although not significant (P = 0.419) the African-descent ALI group had a higher mortality rate (47%) compared to the European-descent ALI group.

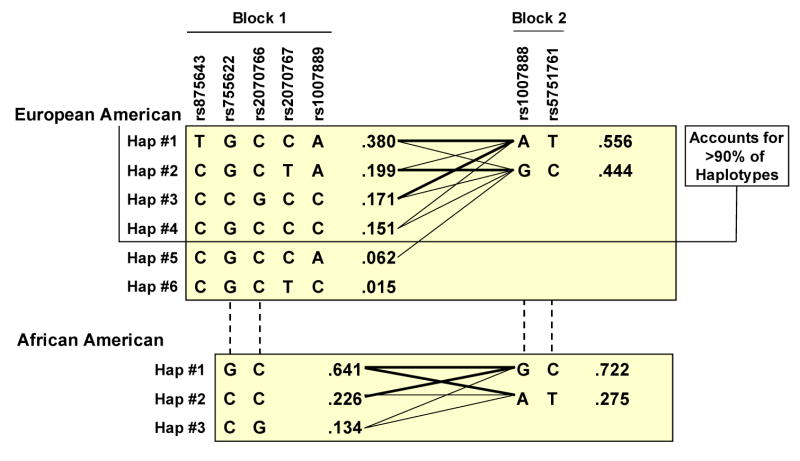

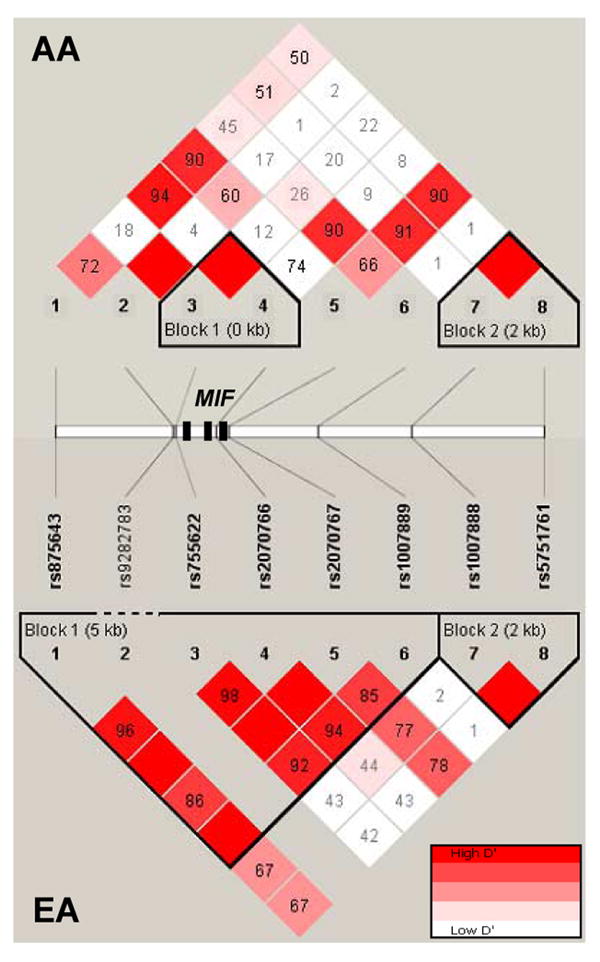

For disease associations, we examined the commonly used −173 G/C polymorphism along with other known MIF SNPs: rs9282783 at position −206 in the MIF promoter, rs2070766 at position +654 within intron 2, and rs2070767 at a position 54 bp downstream from the MIF 3′UTR. These SNPs and an additional set of four polymorphisms from flanking intergenic regions (Table III) were tested for association with susceptibility to sepsis and ALI in two independent populations (European and African descent) across a 9.7-kb region (Figure 4). The average genotyping completion rate for the eight polymorphisms across the two populations was 96.5%. The SNP rs9282783 was found to be monomorphic in European descent Americans. No SNP showed significant departure from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium and LD patterns in the region revealed two haplotype blocks in both populations (Figure 4) with the first block extending 5 kb in European descent Americans, but less than 1 kb in African descent Americans. In both cases, however, more than 90% of variation was defined by a small number of common (≥10%) haplotypes (Figure 5). The complete MIF gene (< 1 kb in length) was included in this block in European descent Americans but contained only the 5′ portion of MIF in African descent Americans. These genomic regional findings overlap with the re-sequencing data from the NIEHS SNPs (http://egp.gs.washington.edu). Using SNPs with MAF>5% in any of the two populations from this database, a 2 kb block (with three common haplotypes) was observed in European descent Americans including the entire MIF gene. However, in African descent Americans, the block was reduced to 1 kb (with two common haplotypes) excluding the 3′ portion (starting in intron 1) of the gene. The second block (2 kb), with two haplotypes defining almost 100% of variation, was common to both populations and was comprised of the two SNPs of the 3′ end region. The multiallelic D' values between the two blocks were 0.25 and 0.67 in African and European Americans, respectively, indicating a low to moderate LD in the region.

Table III.

Chromosome 22 location, minor allele frequency (MAF), and type and nucleotide change of genotyped SNPs in MIF gene region.

| dbSNP ID (build 123) | Location (build 38) | Inter-SNP distance (bp) | MAF (EA/AA)* | Type | Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs875643 | 22,563,998 | 0 | 0.36/0.40 | Intergenic | C/T |

| rs9282783 | 22,566,359 | 2,361 | 0/0.11 | Promoter | C/G |

| rs755622 | 22,566,392 | 33 | 0.17/0.35 | Promoter (−173) | G/C |

| rs2070766 | 22,567,221 | 829 | 0.17/0.11 | Intron 2 (+656) | C/G |

| rs2070767 | 22,567,463 | 242 | 0.22/0.21 | 54bp from 3′UTR | C/T |

| rs1007889 | 22,569,243 | 1,780 | 0.31/0.25 | Intergenic | A/C |

| rs1007888 | 22,571,101 | 1,858 | 0.49/0.27 | Intergenic | A/G |

| rs5751761 | 22,573,736 | 2,635 | 0.48/0.28 | Intergenic | C/T |

EA: European-Americans; AA: African-Americans.

Figure 4. Scheme of the genotyped SNPs and the LD patterns across the analyzed region.

The triangular panels show the pairwise D' values and the significant blocks in African- (AA) and European- descent American (EA) populations. Numbers and color codes in each diamond indicate the magnitude of LD between the pairs of SNPs. The approximate positions of the 8 SNPs along with the exons of the MIF gene (black boxes) are also indicated between the two panels.

Figure 5. Haplotypes of the two detected blocks of MIF gene in European and African descent American patients with ALI and samples.

Fractions next to each haplotype denote frequency observed in the study population specified. The line thickness reflects frequency of adjacent block haplotype distribution (thick lines, > 10%; thin lines, > 1%).

Testing for association of individual SNPs with sepsis and ALI in both European and African American populations showed only a significant crude association of two SNPs in African Americans (Table IV). The associated SNPs were rs755622, when comparing septic patients with controls, and rs2070767, when comparing ALI and septic patients. For rs755622, carriers of CC genotype showed more than 3-fold increased risk to develop sepsis (ORcrude = 3.34, 95% CI: 1.10-10.15; P = 0.027, under a recessive model). However, the association was not significant after including age and gender in a logistic regression model (ORadj = 3.00, 95% CI: 0.53-16.98; P = 0.210). For rs2070767, carriers of the T allele showed ∼2-fold increased risk to develop ALI from sepsis (ORcrude = 2.15, 95% CI: 1.01-4.58; P = 0.045 under a dominant model), but again was not, significant after considering age and gender in the model (ORadj = 1.95, 95% CI: 0.81-4.67; P = 0.130). Although our relatively small sample size limits our ability to conclusively demonstrate any SNP association with mortality, there was a striking trend toward an increased mortality rate in the African descent ALI subjects who carried the risk alleles in either rs755622 (83% for CC versus 20-45% for GG and GC) or rs2070767 (62% for TT and CT versus 39% for CC).

Table IV.

Crude association tests for individual SNPs in MIF gene in African Americans.

| Septic patients compared to Healthy controls | |||||

|

|

|||||

| SNP | Model | Sepsis (%) | Controls (%) | OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|

| |||||

| rs755622 | GG/GC | 54 (83.1) | 82 (94.2) | ||

| CC | 11 (16.9) | 5 (5.8) | 3.34 (1.10-10.15) | 0.03 | |

|

| |||||

| ALI patients compared to Septic patients | |||||

|

|

|||||

| SNP | Model | ALI (%) | Sepsis (%) | OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|

| |||||

| rs2070767 | CC | 31 (55.4) | 48 (72.7) | ||

| CT/TT | 25 (44.6) | 18 (27.3) | 2.15 (1.01-4.58) | 0.04 | |

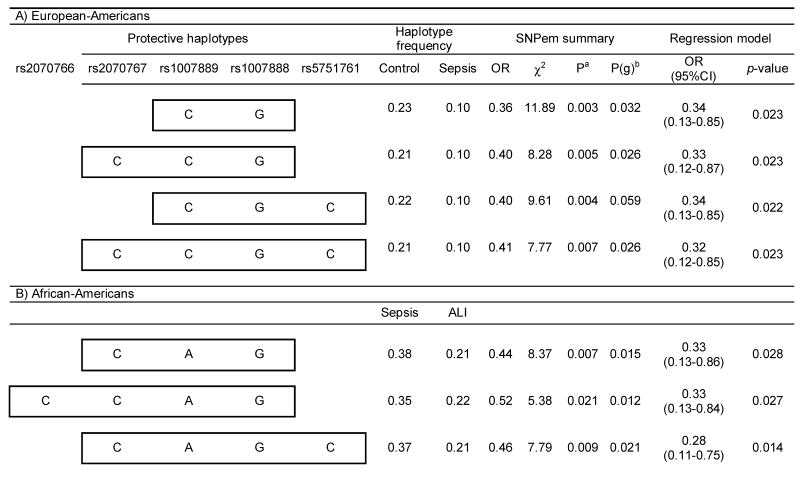

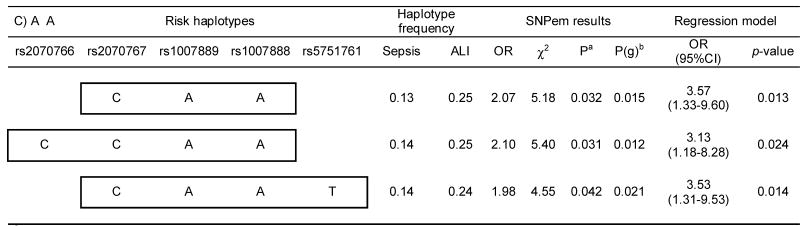

In order to test for haplotype associations with sepsis and ALI, we next performed sliding window analysis comprising 2-4 consecutive SNPs, which provided strong associations of common haplotypes (≥10%) with protection from sepsis development in European Americans, and both protection and risk for ALI development from sepsis in African Americans. These associations remained significant after including age and gender in the logistic regression models (Table V) and identified significant differences in the overall frequency profiles of haplotypes for all but one comparison (P = 0.059). Remarkably, the associated haplotypes overlapped the two existing blocks in both populations with half of the protective haplotypes (European Americans) involving the last SNP (rs2070767) at a position 54 bp from the 3′UTR of the gene. In African Americans, both protective and risk haplotypes were found to either involve one (rs2070767) or two (rs2070766 and rs2070767) of the SNPs of the 3′ end of gene. In addition, the alleles involved in the protective haplotypes in the two populations closely overlapped (with the exception of alleles at rs1007889). Partial overlapping was also found within the African American population between protective and risk haplotypes (excepting the alleles at rs1007888 and rs5751761).

Table V.

Significant associations resulting from the 2-4 SNP sliding window haplotype analysis in European and African Americans.

Based on 10,000 permutations.

Global p-value derived from an “omnibus” likelihood ratio test for assessing the overall haplotype frequency profile differences between the cases and controls.

Finally, we were able to evaluate serum MIF protein levels in a subset of human ALI for which genotype data was available (n=52). We were unable to detect an association between MIF protein level and MIF genotypes including both individually (unadjusted) associated SNPs and the associated haplotypes.

Discussion

Current evidence indicates that both susceptibility and severity of ALI are influenced by the complex interplay between individual genetic influences and the environment.5 Our work18,21 and other published studies are strongly consistent with a genetic basis for ALI. Inbred mouse strains, with lung injury induced by nickel sulfate aerosol or inhaled LPS, demonstrated that ALI susceptibility is heritable.37 Our emphasis on MIF as a biomarker in ALI stems from observations which indicate that the induction of specific cytokine expression after lung injury often correlates with the magnitude of lung damage.38 Comprehensive studies seeking to identify relevant inflammatory mediators and biomarkers in ALI have clarified the complexity of the response with several viable mediators described as potentially central to the development of the fully expressed syndromes with marked recruitment of leukocytes (IL-8, IL-1, LTB4) and profound increases in vascular permeability (TNF-α, IL-1, VEGF). MIF is now recognized as a multifunctional cytokine derived from a variety of cell types, including monocytes/macrophages, endothelium, and epithelium with hormonal and catalytic enzymatic activities of potentially pivotal importance for its proinflammatory role.39,40 Evidence suggesting that MIF may participate in the pathogenesis of ALI includes the observation that MIF increases in the airspaces of ARDS patients correlates with severity,8 and inhibition of MIF activity in murine macrophages resulted in reduced TLR4 expression with hypo-responsiveness to LPS stimulation.12 Despite this strong, albeit indirect, evidence suggesting that MIF may participate in the pathogenesis of ALI, a unified molecular mechanism of action remains to be elucidated.

In order to identify candidate genes involved in ALI pathogenesis, we have employed a multifaceted approach which integrates conserved trends between species in the expression of common groups of genes during ALI41 with cellular pathways and available clinical data. Compared to the complex biological pathways involved in the disease, we derived a reduced list of candidate genes, including previously known ALI genes as well as novel ALI-related genes, for further association studies using ALI patients and controls. For some of these genes we have already assessed their association with ALI susceptibility. PBEF21 and MYLK18 constitute two clear examples of candidate genes derived by utilizing the described methods and for which initial associations with susceptibility to ALI have been provided. Based on this previous success, and using the similar animal models and methods, and previously collected case and control samples, we explored the contribution of MIF to the development of ALI. To ensure the wide applicability of our findings, we employed several animal models of ALI, showing clear biochemical and physiologic evidence of alveolar and endothelial barrier dysfunction with comparable increases in vascular permeability and histologic evidence of lung inflammation, along with BAL and serum samples from patients with sepsis and ALI. We observed a consistent overlap of results among the different models and samples, all showing an increase in the levels of MIF mRNA and protein expression during ALI, findings highly consistent with our prior studies as well as published reports. This conserved increase in MIF levels across different species reinforces the potentially key role of MIF in ALI development, and suggests that MIF is an attractive ALI candidate gene. In vitro experiments were not performed to explore the regulation of MIF expression under stimulations of LPS, TNF-α, IL1-β or mechanical stress (cyclic stretch) as we have reported in other published studies.21 Thrombin was recently reported to induce MIF expression in human endothelial cells suggesting an important role for MIF during cytoskeletal rearrangements associated with inflammation.42 Our lab previously demonstrated that there is an intracellular interaction of myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) with MIF in TNF-α and thrombin-stimulated endothelium, suggesting these gene products may be involved in endothelial activation in ALI.13 Although we didn't further explore the possible protective effect of anti-MIF therapy, MIF knockout mice or mice treated with anti-MIF antibodies were protected from severe sepsis or septic shock induced by LPS.7,12

We evaluated MIF as a susceptibility candidate gene using a case-control association study with eight SNPs selected covering 9.7 kb (the entire gene and surrounding regions). A total of 506 sepsis and ALI patients along with healthy controls from two population groups were genotyped. Although initial (crude) association tests of individual SNPs showed significant results for two MIF SNPs (rs755622 and rs2070767) in African American comparisons, these SNPs were not significant after consideration of other covariates. However, 2-4 SNPs window analyses revealed that haplotypes located in the vicinity of the 3′ end of the MIF gene were highly significantly associated with both sepsis (in European Americans) and ALI (in African Americans), even after covariates were considered.

Sepsis and ALI, in the absence of clear biomarkers, remain to be diagnosed by a compendium of a variety of different clinical signs and symptoms.43,44 In our study, and all other studies conducted to date for sepsis and ALI, cases are not drawn from a clinically homogeneous population, but rather represent a spectrum of overlapping phenotypes. This then creates a potential though it is somehow alleviated by the inclusion of patients according to previously defined inclusion and exclusion criteria.18 Another source of potential bias in our study concerns the use of healthy controls, defined as individuals without any recent acute illness or any chronic illness requiring physician care. A potential selection bias in this study, produced by the possibility that health concerns may have influenced participation as controls, cannot be thus ruled out. A valid alternative would be to use critically ill patients who do not develop sepsis or acute lung injury as controls. Although it may be a superior study, such hospital-based design is not free either of selection bias.45

One limitation of our study is that we did not adjust the statistical tests for the number of windows or the number of disease comparisons. To assess the association, we relied on haplotype windows for which we found significance, empirically determined by randomization (thus giving correct type I error rates), through omnibus likelihood ratio tests. This type of analyses has been criticized 46,47 since windows are chosen without a strong statistical justification generating a large and unnecessary number of non-independent statistical tests. However, sliding SNP windows allows making a comprehensive screening of the region considered. As an example, Barnes et al.48 showed that a haplotype of C3 gene associated with asthma susceptibility would not have been identified if the sliding SNP window approach had not been utilized. Thus, although our results may be a false positive, the associated haplotypes span overlapping regions in European and African Americans, giving consistency to the association.

The human MIF gene (22q11.23) is located ∼10 kb downstream from the solute carrier family 2-member 11 (SLC2A11) and ∼63 kb upstream from GSTT2 (glutathione S-transferase theta 1). An exploration in HapMap49 of the LD patterns in a 120 kb region containing the three genes in Utah residents with ancestry from Northern and Western Europe and in Africans from Ibadan (Nigeria), showed that neither individual SNPs included in the associated haplotypes nor the blocks defined by any of the genotyped SNPs have strong LD with either SLC2A11 or GSTT2 in any of the two populations. Thus, although we cannot rule out population stratification as a possible explanation for the sepsis/ALI associations we have noted, these results suggest that variants in close proximity to the MIF gene modulate sepsis and ALI susceptibility in both European and African Americans.

The SNP rs755622, located at position −173 in the promoter of the gene, has been shown to modulate promoter activity in reporter assays27 although the results are completely dependent on cell type studied Donn et al.27 also showed that, in healthy controls, carriers of the −173C allele showed higher serum levels of MIF protein, compared to −173 GG homozygous. Congruently, this SNP showed a significant (crude) association with the genotype CC increasing the risk for sepsis, but it was no longer significant after considering gender and age in the model. This effect was only observed in African Americans, since we did not observe significant association of this SNP in European Americans. We recognize however, that due to sample size and a MAF<20% in this population, our design is underpowered to detect effects in the order of OR∼2.0. Baugh et al.50 also showed in reporter assays that the CATT(5-8) microsatellite, located in the promoter of MIF gene and in linkage disequilibrium with rs755622, determined the activity of the promoter by the number of repeats. Contrary to these studies, our major findings are focused on the 3′UTR region of the gene, and do not involve individual SNPs but rather involve haplotypes, a finding that is not surprising given the greater power of haplotype analyses.34

Messenger RNA in eukaryotes is under regulated control, often through regulatory elements in the 3′UTR such as AU-rich elements that regulate mRNA stability51,52 as well as signals that regulate the subcellular localization of transcripts.53 Our results, however, do not imply a direct role of variants of the 3′UTR in either functionality or susceptibility. It must be noted that the studied region is relatively small and, as shown, linkage disequilibrium extends in the ∼10 kb region screened. In addition, we only studied a limited amount of known variation in the region, and there is a chance that other untyped (known or unknown) variation may be causal for the association (e.g. involving variation for which there is already evidence of functionality, as the case of rs755622 or the CATT microsatellite), so that the associated haplotypes in the 3′UTR would be surrogates for that variation.

In summary, our results, utilizing a combination of functional genomic and genetic epidemiological approaches, provide novel insights into the molecular mechanisms of ALI. MIF is up-regulated at both the mRNA and protein levels in the setting of ALI (observed across several species), and population-specific MIF gene haplotypes appear to be associated with sepsis and ALI susceptibility in Americans of both European- and African- descent. This is particularly intriguing given the expanding number of reports implicating a disparate susceptibility to and severity of ALI54 and sepsis55 among these two population groups. Our results should encourage additional studies to replicate MIF associations and its utility as a predictive biomarker in ALI.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by awards from the National Heart Lung Blood Institute HopGene PGA Program in Genomic Applications (NIH HL 69084, JGNG PI), Program Project Grant (HL 58064, JGNG), the Specialized Center for Clinical Oriented Research (SCCOR) award (HL 73994), and the Lowell T. Coggeshall endowment at the University of Chicago (JGNG). We are very grateful to Christine Metz for sharing the mouse anti-MIF antibody, all CELEG study coordinators, Daniele Fallin for providing access to SNPem, and Tera Lavoie, Saad Sammani, James E. Watkins and William Shao for excellent technical assistance. L.G is supported in part by NIH T32 training grant. CF was supported by Fundacion Canaria Dr. Manuel Morales. KCB was supported in part by the Mary Beryl Patch Turnbull Scholar Program.

Abbreviations

- ALI

acute lung injury

- ARDS

acute respiratory distress syndrome

- BAL

bronchoalveolar lavage

- HVT

high tidal volume ventilation

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- LD

linkage disequilibrium

- MIF

macrophage migration inhibitory factor

- SNP

single-nucleotide polymorphism

- VALI

ventilator-associated ALI

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network. N Engl J Med. 2000 May 4;342(18):1301–1308. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ware LB, Matthay MA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000 May 4;342(18):1334–1349. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slutsky AS, Tremblay LN. Multiple system organ failure. Is mechanical ventilation a contributing factor? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998 Jun;157:1721–1725. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.6.9709092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kleeberger SR, Peden D. Gene-environment interactions in asthma and other respiratory diseases. Annu Rev Med. 2005;56:383–400. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.56.062904.144908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flores C, Ma SF, Maresso K, Ahmed O, Garcia JG. Genomics of acute lung injury. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2006 Aug;27(4):389–395. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-948292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Renner P, Roger T, Calandra T. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor: gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to inflammatory diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2005 Nov 15;41 7:S513–519. doi: 10.1086/432009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernhagen J, Calandra T, Mitchell RA, Martin SB, Tracey KJ, Voelter W, et al. MIF is a pituitary-derived cytokine that potentiates lethal endotoxaemia. Nature. 1993 Oct 21;365(6448):756–759. doi: 10.1038/365756a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo Y, Xie C. The pathogenic role of macrophage migration inhibitory factor in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2002 Jun;25(6):337–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beishuizen A, Thijs LG, Haanen C, Vermes I. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor and hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal function during critical illness. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001 Jun;86(6):2811–2816. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.6.7570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baugh JA, Bucala R. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor. Crit Care Med. 2002 Jan;30 1:S27–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donnelly SC, Haslett C, Reid PT, Grant IS, Wallace WA, Metz CN, et al. Regulatory role for macrophage migration inhibitory factor in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Nat Med. 1997 Mar;3(3):320–323. doi: 10.1038/nm0397-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roger T, Froidevaux C, Martin C, Calandra T. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) regulates host responses to endotoxin through modulation of Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) J Endotoxin Res. 2003;9(2):119–123. doi: 10.1179/096805103125001513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wadgaonkar R, Dudek SM, Zaiman AL, Linz-McGillem L, Verin AD, Nurmukhambetova S, et al. Intracellular interaction of myosin light chain kinase with macrophage migration inhibition factor (MIF) in endothelium. J Cell Biochem. 2005 Jul 1;95(4):849–858. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garcia JG, Davis HW, Patterson CE. Regulation of endothelial cell gap formation and barrier dysfunction: role of myosin light chain phosphorylation. J Cell Physiol. 1995 Jun;163(3):510–522. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041630311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dudek SM, Garcia JG. Cytoskeletal regulation of pulmonary vascular permeability. J Appl Physiol. 2001 Oct;91(4):1487–1500. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.4.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia JG, Verin AD, Herenyiova M, English D. Adherent neutrophils activate endothelial myosin light chain kinase: role in transendothelial migration. J Appl Physiol. 1998 May;84(5):1817–1821. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.84.5.1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petrache I, Verin AD, Crow MT, Birukova A, Liu F, Garcia JG. Differential effect of MLC kinase in TNF-alpha-induced endothelial cell apoptosis and barrier dysfunction. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001 Jun;280(6):L1168–1178. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.6.L1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao L, Grant A, Halder I, Brower R, Sevransky J, Maloney JP, et al. Novel Polymorphisms in the Myosin Light Chain Kinase Gene Confer Risk for Acute Lung Injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006 Apr;34(4):487–95. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0404OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flores C, Ma SF, Maresso K, Ober C, Garcia JG. A variant of the myosin light chain kinase gene is associated with severe asthma in African Americans. Genet Epidemiol. 2007 Jan 31; doi: 10.1002/gepi.20210. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peng X, Hassoun PM, Sammani S, McVerry BJ, Burne MJ, Rabb H, et al. Protective effects of sphingosine 1-phosphate in murine endotoxin-induced inflammatory lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004 Jun 1;169(11):1245–1251. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200309-1258OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ye SQ, Simon BA, Maloney JP, Zambelli-Weiner A, Gao L, Grant A, et al. Pre-B-cell colony-enhancing factor as a potential novel biomarker in acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005 Feb 15;171(4):361–370. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200404-563OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McVerry BJ, Peng X, Hassoun PM, Sammani S, Simon BA, Garcia JG. Sphingosine 1-phosphate reduces vascular leak in murine and canine models of acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004 Nov 1;170(9):987–993. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200405-684OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simon BA, Easley RB, Grigoryev DN, Ma SF, Ye SQ, Lavoie T, Tuder RM, Garcia JG. Microarray analysis of regional cellular responses to local mechanical stress in acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006 Nov;291(5):L851–61. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00463.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bernard GR, Artigas A, Brigham KL, Carlet J, Falke K, Hudson L, et al. The American-European Consensus Conference on ARDS. Definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994 Mar;149(3 Pt 1):818–824. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.3.7509706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Conference: definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. Crit Care Med. 1992 Jun;20(6):864–874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985 Oct;13(10):818–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donn R, Alourfi Z, De Benedetti F, Meazza C, Zeggini E, Lunt M, et al. Mutation screening of the macrophage migration inhibitory factor gene: positive association of a functional polymorphism of macrophage migration inhibitory factor with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002 Sep;46(9):2402–2409. doi: 10.1002/art.10492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barton A, Lamb R, Symmons D, Silman A, Thomson W, Worthington J, et al. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) gene polymorphism is associated with susceptibility to but not severity of inflammatory polyarthritis. Genes Immun. 2003 Oct;4(7):487–491. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nohara H, Okayama N, Inoue N, Koike Y, Fujimura K, Suehiro Y, et al. Association of the −173 G/C polymorphism of the macrophage migration inhibitory factor gene with ulcerative colitis. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39(3):242–246. doi: 10.1007/s00535-003-1284-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Donn RP, Plant D, Jury F, Richards HL, Worthington J, Ray DW, et al. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor gene polymorphism is associated with psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2004 Sep;123(3):484–487. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sole X, G E, Valls J, Iniesta R, Moreno V. SNPStats: a web tool for the analysis of association studies. Bioinformatics. 2006 Aug;22(15):1928–9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005 Jan 15;21(2):263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gabriel SB, Schaffner SF, Nguyen H, Moore JM, Roy J, Blumenstiel B, et al. The structure of haplotype blocks in the human genome. Science. 2002 Jun 21;296(5576):2225–2229. doi: 10.1126/science.1069424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fallin D, Cohen A, Essioux L, Chumakov I, Blumenfeld M, Cohen D, et al. Genetic analysis of case/control data using estimated haplotype frequencies: application to APOE locus variation and Alzheimer's disease. Genome Res. 2001 Jan;11(1):143–151. doi: 10.1101/gr.148401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCaskie PA, C K, Palmer LJ. SimHap: A comprehensive modeling framework and a simulation-based approach to haplotypic analysis of population-based data. Western Australian Institute for Medical Research, University of Western Australia; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lai KN, Leung JC, Metz CN, Lai FM, Bucala R, Lan HY. Role for macrophage migration inhibitory factor in acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Pathol. 2003 Apr;199(4):496–508. doi: 10.1002/path.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prows DR, McDowell SA, Aronow BJ, Leikauf GD. Genetic susceptibility to nickel-induced acute lung injury. Chemosphere. 2003 Jun;51(10):1139–1148. doi: 10.1016/S0045-6535(02)00710-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Armstrong L, Millar AB. Relative production of tumour necrosis factor alpha and interleukin 10 in adult respiratory distress syndrome. Thorax. 1997 May;52(5):442–446. doi: 10.1136/thx.52.5.442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Calandra T, Froidevaux C, Martin C, Roger T. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor and host innate immune defenses against bacterial sepsis. J Infect Dis. 2003 Jun 15;187 2:S385–390. doi: 10.1086/374752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Calandra T, Roger T. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor: a regulator of innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003 Oct;3(10):791–800. doi: 10.1038/nri1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grigoryev DN, Finigan JH, Hassoun P, Garcia JG. Science review: searching for gene candidates in acute lung injury. Crit Care. 2004 Dec;8(6):440–447. doi: 10.1186/cc2901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shimizu T, Nishihira J, Watanabe H, Abe R, Honda A, Ishibashi T, et al. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor is induced by thrombin and factor Xa in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2004 Apr 2;279(14):13729–13737. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400150200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Riedemann NC, Guo RF, Ward PA. The enigma of sepsis. J Clin Invest. 2003 Aug;112(4):460–467. doi: 10.1172/JCI19523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parsons PE. Bridging the chasm between bench and bedside: translational research in acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004 Jun;286(6):L1086–1087. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00040.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vineis P, McMichael AJ. Bias and confounding in molecular epidemiological studies: special considerations. Carcinogenesis. 1998 Dec;19(12):2063–2067. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.12.2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Browning SR. Multilocus association mapping using variable-length Markov chains. Am J Hum Genet. 2006 Jun;78(6):903–913. doi: 10.1086/503876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nicolae DL. Testing untyped alleles (TUNA)-applications to genome-wide association studies. Genet Epidemiol. 2006 Dec;30(8):718–727. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barnes KC, Grant AV, Baltadzhieva D, Zhang S, Berg T, Shao L, et al. Variants in the gene encoding C3 are associated with asthma and related phenotypes among African Caribbean families. Genes Immun. 2006 Jan;7(1):27–35. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.The International HapMap Project. Nature. 2003 Dec 18;426(6968):789–796. doi: 10.1038/nature02168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baugh JA, Chitnis S, Donnelly SC, Monteiro J, Lin X, Plant BJ, et al. A functional promoter polymorphism in the macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) gene associated with disease severity in rheumatoid arthritis. Genes Immun. 2002 May;3(3):170–176. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mitchell P, Tollervey D. mRNA turnover. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001 Jun;13(3):320–325. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mendell JT, Dietz HC. When the message goes awry: disease-producing mutations that influence mRNA content and performance. Cell. 2001 Nov 16;107(4):411–414. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00583-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jansen RP. mRNA localization: message on the move. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001 Apr;2(4):247–256. doi: 10.1038/35067016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moss M, Mannino DM. Race and gender differences in acute respiratory distress syndrome deaths in the United States: an analysis of multiple-cause mortality data (1979- 1996) Crit Care Med. 2002 Aug;30(8):1679–1685. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200208000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Martin GS, Mannino DM, Eaton S, Moss M. The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N Engl J Med. 2003 Apr 17;348(16):1546–1554. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]